1. Introduction

The English dative alternation has long served as a valuable testing ground for theories of language acquisition. For L2 learners, producing ditransitive constructions involves not only acquiring the morphosyntactic frames themselves, but also mapping them onto conceptual roles, such as recipients and themes. This makes the alternation a useful window into the broader question of how learners establish form–meaning correspondences under the influence of both language-specific distributions and general cognitive principles.

A central debate in this line of studies concerns the extent to which mappings between syntax and conceptual roles are universal or learned from experience. One influential view, articulated most prominently by Pinker (Reference Pinker1989), holds that the correspondence between constructions and meanings is grounded in innate cognitive universals. On this account, constraints such as the preference for double-object constructions when the recipient is animate are not acquired through exposure but reflect fundamental properties of human cognition. If such constraints are universal, they should be observable not only in native language acquisition but also in second language learning, regardless of learners’ first language backgrounds. In contrast, usage-based and constructionist approaches (e.g., Ambridge, Reference Ambridge2013; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2011) emphasize the role of statistical learning. Learners are assumed to track the distributional patterns in their input, gradually building constructional knowledge by detecting verb-specific biases and frequency-based tendencies. On this view, constraints such as animacy or pronominality effects are not prespecified but emerge over time as learners accumulate evidence from usage. From this perspective, L2 acquisition is expected to show developmental trajectories in which sensitivity to distributional cues increases with proficiency. Recent research suggests that these perspectives are not mutually exclusive but rather capture complementary aspects of the learning process. Previous studies of L2 acquisition indicate that while highly proficient learners are sensitive to distributional statistics, their choices are also constrained by broader semantic principles (Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024). The key question, therefore, is not whether semantic universals or statistical learning drive acquisition, but how and when each of these factors exerts its influence.

The present study investigates these issues through a large learner corpus analysis of English dative constructions. Specifically, we ask at which proficiency levels learners show sensitivity to animacy, pronominality, constituent length and verb bias, and how these factors shape their choice between the double-object and prepositional-object constructions. The results bear on the more general issue of how structural choices are mapped onto conceptual categories, an issue central to theories of L2 acquisition and cognition.

2. Background

2.1. Logical problem of learning dative alternation

Alternation is a phenomenon in which two constructions represent a single situation and are interchangeable under certain conditions. Dative alternation refers to the alternation between a double-object (DO) construction like John gave Mary a book and a prepositional object (PO) construction like John gave a book to Mary.

The phenomenon of dative alternation has attracted considerable attention from linguists. Extensive research on this topic covers both formal aspects (e.g., Beck & Johnson, Reference Beck and Johnson2004; Larson, Reference Larson1988; Rappaport Hovav & Levin, Reference Rappaport Hovav and Levin2008) and how individuals perceive and interpret their experiences, referred to as the construal of the content of consciousness, in relation to situations expressed by a dative construction (Langacker, Reference Langacker1986, Reference Langacker2008; Pinker, Reference Pinker1989, Reference Pinker2007).

Turning to aspects of language acquisition, the logical difficulty in learning these constructions is also problematic. The following examples illustrate this difficulty:

As shown in (1) and (3), these two variants are largely alterable. Therefore, if an infant is exposed to such examples and makes rational generalizations, one might expect them to acquire the knowledge that the DO structure [X V Z Y] and PO structure [X V Y to Z] are interchangeable. However, these variants are not always interchangeable, as demonstrated in (2) and (4). Indeed, children make errors in generalization, like those in (2) and (4), in the early stages of their acquisition, but soon learn which variant is compatible with which verb. Importantly, children learn not only which constructions are acceptable but also which ones are not solely based on positive input.Footnote 1

Pinker’s solution to the logical problem of this phenomenon is based on the idea that the dative alternation reflects underlying semantic structures. According to Pinker (Reference Pinker1989), this alternation involves two thematic cores. One is X causes Y to go to Z, resulting in the PO structure [X V Y to Z] in syntax and the other is X causes Z to have Y, leading to the DO structure [X V Z Y] in syntax. During language production, these rules, which are known as the linking rules, transform semantic structures into argument structures. They associate the agent (“X” in the thematic cores of both PO and DO) with the subject, the theme (“Y” in the thematic core of PO) and the recipient or possessor (“Z” in the thematic core of DO) with an object, the possessed entity (“Y” in the thematic core of DO) with another object and the goal (“Z” in the thematic core of PO) with the oblique argument, among others. Pinker (Reference Pinker1989) argues that these linking rules are used universally across all languages, and do not need to be learned from input.

Interestingly, children are known to overgeneralize rules and produce nontarget-like constructions (e.g., *John pushed Mary a ball.) before they retreat from overgeneralization and are able to use dative constructions in an adult-like manner. One hypothesis explaining the phenomenon of overgeneralization and retreat is based on the concepts of broad- and narrow-range rules presented by Gropen et al. (Reference Gropen, Pinker, Hollander, Goldberg and Wilson1989). The broad-range rule operates as a general mechanism that predicts the properties necessary for a verb to undergo a specific alternation. For dative alternation, this rule stipulates that a verb must be semantically compatible with the thematic core mentioned above. This rule sets a broad stage by defining the types of verbs that can potentially undergo alternation based on their semantic properties. Learning the broad-range rule involves learning that [X V Z Y] and [X V Y to Z] can be used interchangeably with the same verb if the verb expresses some kind of transfer. In contrast, the narrow-range rule applies this broad principle more specifically, predicting the actual use of dative alternations for particular sets of verbs that share the same semantic category. Over time, through exposure to linguistic input and the gradual acquisition of narrow-range rules, children refine their understanding and usage, restricting alternation to appropriate verbs. This process illustrates how children align their language use with adult norms and avoid overgeneralization errors.

Other researchers argue that children equipped with statistical learning abilities have sufficient capacity to learn constructions and their corresponding semantics. For example, negative entrenchment (Ambridge et al., Reference Ambridge, Pine and Rowland2012, Reference Ambridge, Barak, Wonnacott, Bannard and Sala2018; Stefanowitsch, Reference Stefanowitsch2008) is a type of frequency effect that involves probabilistic inferences drawn by learners when they repeatedly encounter verbs in specific contexts. In the context of dative alternation, negative entrenchment occurs when a verb is frequently used in either construction in such a way as to reduce its acceptability in the other construction. For instance, when learners frequently encounter the verb push used only in the PO construction, they infer that its use in DO and other constructions is unacceptable. Statistical preemption is also a competition-driven statistical learning mechanism. Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2011) defined preemption as follows: “A verb i is preempted from appearing in a construction A, CxA, if and only if the following probability is high: P(CxB|context that would be suitable for CxA and verb i)” (p. 131). Preemption can be illustrated through the example of the verb “explain” in English, where it typically avoids appearing in the double-object construction (e.g., *“Explain me this”). Instead, the more conventional phrasing is “Explain this to me,” which appears overwhelmingly in contexts where the double-object construction might otherwise be used. This suggests that the frequent exposure to the preemptive construction “Explain this to me” restricts the use of “explain” in the double-object construction. Conversely, verbs like “tell” easily occur in both constructions (e.g., Tell him a story and Tell a story to him), making “tell” more flexible in its syntactic patterns (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019).

Such statistical information has been formalized and statistically quantified as indices representing a verb’s preference for one construction over competing alternatives, and often used to explain how learners retreat from overgeneralization errors in L1 (e.g., Ambridge et al., Reference Ambridge, Pine, Rowland, Jones and Clark2009, Reference Ambridge, Pine, Rowland and Chang2012, Reference Ambridge, Pine, Rowland, Freudenthal and Chang2014; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995) and L2 acquisitions (e.g., Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024; Xiang & Chang, Reference Xiang and Chang2023; Zhang, Reference Zhang2017; Zhang & Mai, Reference Zhang and Mai2018). There is still considerable debate on whether the acquisition of verb-specific construction preferences is driven by an innate, top-down mechanism or learned through a statistical, bottom-up process. English-acquiring infants must acquire the dative alternation despite limited input, a challenge widely discussed as part of the logical problem of acquisition. This line of research has played an important role in theoretical debates on universality and language-specificity. While the present study focuses on L2 adult learners, findings from L1 acquisition are invoked here as a contrasting reference point that helps situate our investigation within the broader discussion of universality and particularity in language acquisition.

2.2. L2 acquisition studies and acquisition of dative alternation

Research on second language acquisition of the dative alternation has often been framed in terms of a tension between universality and language-specificity. On the one hand, learners appear to rely on conceptual universals, which are predicted to apply regardless of language background (e.g., Mazurkewich, Reference Mazurkewich1985). On the other hand, learners are also demonstrably sensitive to distributional information in the input, including verb-specific biases and frequency patterns (e.g., Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024; Xiang & Chang, Reference Xiang and Chang2023). Recent studies show that these two sources of information are not mutually exclusive: as proficiency increases, L2 learners make more consistent use of both statistical tendencies and semantic constraints in their production. The focus of such research indicates that L2 studies deserve attention as a field within cognitive science, regardless of whether they concern the acquisition of a single construction such as the dative alternation.

Early research on the acquisition of the English dative alternation discussed the developmental sequence between the prepositional and double-object constructions in terms of markedness, a concept originating in Universal Grammar (UG). While Mazurkewich (Reference Mazurkewich1985) proposed that the prepositional dative is less marked and thus acquired earlier than the double-object dative, Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1987) argued that the development of the English dative alternation proceeds through lexical diffusion, that is, a gradual extension of alternation patterns across individual verbs, and that such progression reflects learning complexity rather than any principle of UG.

Subsequent work, however, has moved beyond such markedness accounts toward explanations grounded in lexical and semantic constraints. Later L2 studies have investigated the acquisition of broad-range and narrow-range rules as universal constraints. However, the findings have been inconsistent. Bley-Vroman and Yoshinaga (Reference Bley-Vroman and Yoshinaga1992) examined whether Japanese adult learners of English possess knowledge of both broad and narrow rules. Their results suggest that while L2 learners were able to distinguish between real ditransitive verbs that allow dative alternation and those that do not, they showed limited ability to differentiate newly created verbs that were artificially made to be dative-possible or dative-impossible. In contrast, other studies have shown that Chinese and Japanese L2 learners are capable of distinguishing particular verb classes (Inagaki, Reference Inagaki1997; Qi & Hang, Reference Qi and Wang2020; Sawyer, Reference Sawyer1995).

More recently, approaches influenced by usage-based models and corpus linguistics have become prominent (e.g., Bresnan et al., Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina, Baayen, Bouma, Kraemer and Zwarts2007; Bresnan & Ford, Reference Bresnan and Ford2010; Jäschke & Plag, Reference Jäschke and Plag2016). In usage-based theories, the acquisition of linguistic structures is viewed as a gradual learning process based on exposure to rich input and frequency effects. In addition, the choice of constructions is considered to vary probabilistically depending on a range of other factors. This line of research is exemplified by Bresnan et al. (Reference Bresnan, Cueni, Nikitina, Baayen, Bouma, Kraemer and Zwarts2007), who showed that native speakers’ choice of dative structure was strongly influenced by variables such as the length of the noun phrase, definiteness and animacy. Their statistical model predicted the choice of dative construction with an accuracy of 94%. Jäschke and Plag (Reference Jäschke and Plag2016) investigated the impact of probabilistic grammatical factors on dative alternations in English among advanced German EFL learners. In their study, participants were asked to perform a sentence-rating task, and their responses were statistically modeled based on a number of predictor variables. The results suggest that learners are sensitive to the same factors as native English speakers, despite the lack of straightforward mapping between German and English dative structures. Xiang and Chang (Reference Xiang and Chang2023) extended this study by investigating the factors influencing Chinese EFL learners’ choices of English dative alternation. In their study, both advanced and intermediate learners performed an acceptability judgment task that featured the selection of 30 dative alternations drawn from a spoken corpus. They also examined the effect of the statistical information of verbs by including entrenchment and statistical preemption indices. The results showed that intermediate learners relied mainly on one factor (pronominality), while advanced learners were sensitive to multiple factors. In addition, Xiang et al. (Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024) have demonstrated that L2 learners are guided both by distributional information, such as verb-specific biases, and by semantic generalizations tied to verb-semantic structure via universal constraints. Evidence from Chinese EFL learners indicates that sensitivity to these constraints increases with proficiency, lending support to usage-based approaches. Importantly, the two are not mutually exclusive: the semantic salience of particular dative verbs may encode both categorical and gradient probabilistic selectional information, suggesting an interaction between semantic generalizations over verb types and distributional learning. This suggests that universality and statistical learning may both play essential roles in L2 acquisition of the dative alternation, a possibility that the present study is well placed to explore.

Several studies have examined the probabilistic nature of construction choice in L2, not only in acceptability judgments but increasingly in production as well. Song and Sung (Reference Song and Sung2017) conducted a corpus-based study examining how Korean EFL learners use dative alternation in English, focusing on the influence of lexical verbs, syntactic weights and information structure. Their findings reveal that learners overuse the PO, even in contexts where native speakers would typically opt for the DO. This over-reliance on PO suggests that Korean learners struggle with applying contextual cues. The study also highlights difficulties in recognizing verb-specific biases, such as certain verbs that prefer one construction over the other, further complicating learners’ ability to produce target-like constructions. Gan (Reference Gan2024) also analyzed how Chinese learners navigate the alternation in both spoken and written registers. The study revealed that learners show some alignment with native speakers in terms of their sensitivity to factors like animacy and pronominality. Notable differences were observed between learners’ sensitivity to verb sense and noun frequency and those of native speakers. This study also highlighted the role of register in shaping the dative alternation, showing that Chinese learners’ choices differed depending on whether they were producing written or spoken English. This suggests that while learners are progressing toward target-like usage, challenges remain in balancing multiple linguistic and cognitive factors across different contexts.

2.3. Toward the present study

The studies mentioned above suggest that while advanced learners incorporate relatively more factors when choosing dative constructions, intermediate or lower-proficiency learners are much less sensitive to these factors. It is assumed that they gradually develop the ability to utilize the factors governing their choice between the two dative constructions. However, little is known about at which developmental stage each factor exerts influence in dative alternation. For example, as mentioned earlier, a wide range of syntactic-, semantic- and discourse-level factors influence the choice of dative constructions, and their acquisition is unlikely to occur simultaneously.

What sets this study apart is its focus on capturing L2 learner development in detail. While Xiang and Chang (Reference Xiang and Chang2023), for example, examine differences between intermediate and advanced learners, their dichotomization of proficiency levels fails to capture the more gradual and continuous nature of developmental change. In addition, as mentioned above, dative alternation involves a developmental process in which children initially overgeneralize rules and produce nontarget-like constructions, and later stop using them (i.e., they no longer produce ungrammatical constructions). This tendency in L1 children was originally observed in production data, and Pinker’s explanation of learnability was also derived from production (e.g., Gropen et al., Reference Gropen, Pinker, Hollander, Goldberg and Wilson1989, Reference Gropen, Pinker, Hollander and Goldberg1991). This highlights the critical importance of examining L2 production data in the studies focusing on developmental changes in the statistical nature of construction choice. Studies that focus on production have explored differences between native speakers and learners, but they have yet to address developmental changes across different proficiency levels.

The present study focuses on L2 production by using a large-scale cross-linguistic corpus; It statistically accounts for differences across learners’ first languages and closely examines the gradual developmental changes in constructional choice. The aim is to identify which factors influence the choice of dative constructions and at what stage of development they begin to exert their effects. This study focuses on animacy of recipient, pronominality of noun phrases, length of noun phrases and statistical verb effect, exploring at which developmental stages each begins to affect construction choice. These factors are certainly not exhaustive, but they have been identified in previous research as those that L2 learners eventually become able to utilize, are feasible to extract from corpus data, and allow for theoretical predictions.

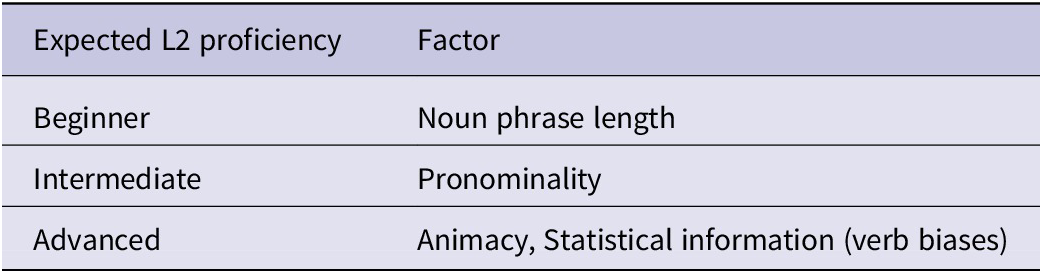

Although no studies have comprehensively and directly investigated the factors that gradually influence the developmental stage as mentioned above, we can make some predictions. First, noun phrase length is likely to affect construction selection across all L2 proficiency levels because it involves processing strategies independent of individual languages. A longer phrase is typically positioned at the end because of ‘the principle of end weight’ (Wasow, Reference Wasow2002). This is explained in terms of language users’ strategies of processing economy. Longer noun phrases are associated with higher processing costs, regardless of the learner’s proficiency level.

Second, pronominality is hypothesized to affect construction selection, starting at an intermediate level. It has been widely observed that previously mentioned or given information is presented before new information (e.g., Collins, Reference Collins1995; Wasow, Reference Wasow2002). Intermediate learners have been reported to use discourse-level information (e.g., new or given information) when selecting constructions (Marefat, Reference Marefat2005). Unlike noun phrase length, which pertains to sentence-level issues, pronominality is a discourse-level phenomenon to which only intermediate- or higher-level learners are sensitive. Therefore, pronominality is likely to be used only at intermediate or higher levels.

Third, only high-proficiency learners are expected to be sensitive to animacy because their use requires an understanding of the association between the semantic differences between the two constructions and the animacy of the recipient in each construction. Langacker (Reference Langacker1986, Reference Langacker2008) suggests that the PO construction focuses on the movement of the theme, as the path is highlighted by the preposition to. In contrast, the DO construction emphasizes the interaction between the agent and the recipient, focusing on the transfer of ownership. As a result, the DO construction typically requires an animate recipient because the interaction presupposes animate agents and recipients. Hence, in the PO construction, a term like the zoo might refer to either a place or an institution, but only the latter in the DO construction. Thus, recipient animacy is considered to have an important role in determining construction. A previous study has shown that animacy information is not exploited by learners at intermediate or low proficiency levels (Xiang & Chang, Reference Xiang and Chang2023).

Fourth, regarding statistical verb effect, Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2019) predicted that learning from such statistical information would be extremely difficult for L2 learners. Empirical studies based on usage-based models have reported that verb bias influences the choice of dative constructions only among high-proficiency L2 learners. In addition, it has been empirically demonstrated that L2 learners are influenced by competing alternatives to a lesser extent than native speakers and that intermediate- or lower-proficiency learners cannot utilize statistical information (Jäschke & Plag, Reference Jäschke and Plag2016; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024; Xiang & Chang, Reference Xiang and Chang2023). This measure represents a verb-by-verb tendency of native speakers. If this effect is identified later in development, it indicates that the learner has learnt statistical information and has achieved retreat from non-normative use of constructions, including overgeneralization. In previous studies that combined research on receptive processing and corpus analysis, a measure like this has been widely used to observe such retreat (e.g., Ambridge, Reference Ambridge2013; Ambridge et al., Reference Ambridge, Pine and Rowland2012, Reference Ambridge, Pine, Rowland, Freudenthal and Chang2014, Reference Ambridge, Barak, Wonnacott, Bannard and Sala2018; Ambridge & Brandt, Reference Ambridge and Brandt2013; Blything et al., Reference Blything, Ambridge and Lieven2014). Thus, examining whether this factor influences learners’ constructional choices is considered to make a significant contribution to the viability of the bottom-up language acquisition process. This study further provides new evidence to the learnability of L2 by describing when (or if) it starts to have an impact at different stages of development. Table 1 summarizes these predictions.

Table 1. Predicted L2 proficiency levels for each factor influencing dative alternation

3. Methods

3.1. Data

The data for this study were obtained from the EF-Cambridge Open Language Database (EFCAMDAT; Geertzen et al., Reference Geertzen, Alexopoulou, Korhonen, Millar, Martin, Eddington, Henery, Miguel, Tseng, Tuninetti and Walter2014), a large-scale longitudinal corpus of learner writing from Englishtown,Footnote 2 an online English language school run by EF Education First. For our research, we utilized a cleaned subset of this corpus, known as the EFCAMDAT Cleaned Subcorpus (Shatz, Reference Shatz2020). This subset includes learner writing across 15 Englishtown proficiency levels, from A1 to C1 levels according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). In this study, we use ‘development’ as an operational term referring to learners’ proficiency levels as indicated by CEFR bands in EFCAMDAT.Footnote 3 The levels are aligned with Englishtown levels, where levels 1–3 correspond to A1, levels 4–6 correspond to A2 and so on. When learners joined Englishtown, their starting proficiency levels were determined by a placement test. At the end of each level, their essays were graded by teachers, and only learners who passed were allowed to progress to the next level.Footnote 4 Furthermore, each Englishtown level is broken down into eight or six units, depending on the subcorpus. At the end of each unit, the students were asked to complete a free writing task, which served as the primary data source for EFCAMDAT. These tasks cover a wide range of topics, including narrative tasks (e.g., [After the beginning of a story is given] “Decide what happens to John and Isabella. Write the final part of the story for your friend.”), descriptive tasks (e.g., “You just ate a very bad meal at a restaurant. Write a complaint in the complaints book. Follow the guidelines below… . You ate a starter, a main course and dessert. You drank red wine and coffee. All your meal was horrible. Describe what you ate and the bad taste”), and what Alexopoulou et al. (Reference Alexopoulou, Michel, Murakami and Meurers2017) termed professional tasks (e.g., [With a job advertisement provided on a previous screen] “Read the information in the internet job advertisement. Write your own personal resume for the job.”) (see Alexopoulou et al., Reference Alexopoulou, Michel, Murakami and Meurers2017; Michel et al., Reference Michel, Murakami, Alexopoulou and Meurers2019, for further details). The subcorpus comprises texts from learners of 11 different nationalities, covering 10 first languages (L1s), including Brazilian Portuguese, Mandarin Chinese, Russian, Arabic, Spanish, German, Italian, French, Japanese and Turkish, in the order of the amount of data available. The length requirement for these writing assignments increases with learners’ proficiency level, starting at 20–40 words for level 1 and reaching 150–180 words for level 15.

3.2. Retrieval of dative constructions

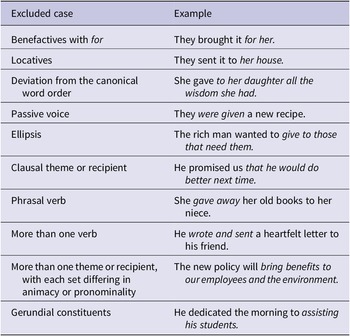

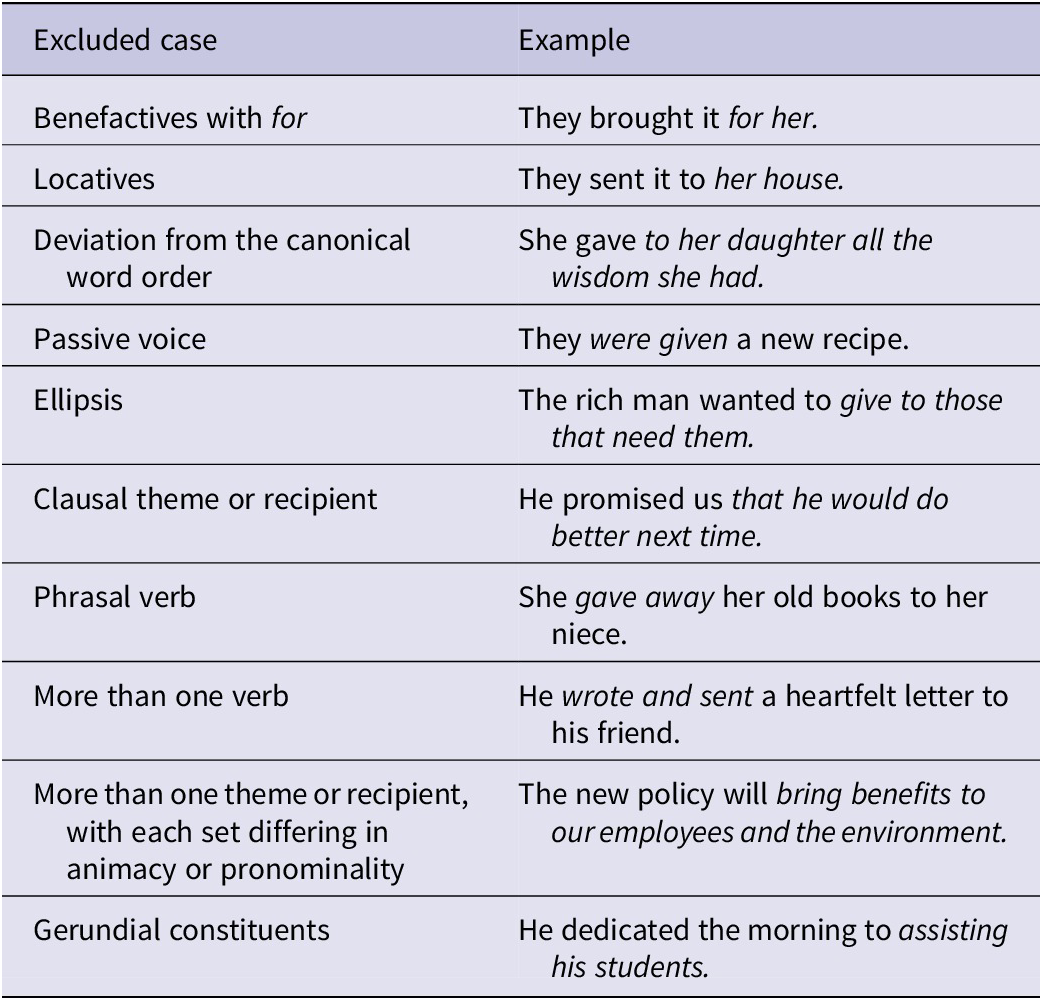

In our study, we operationally defined DO and PO constructions as linguistic patterns following the VERB + RECIPIENT + THEME format for DO and the VERB + THEME + to + RECIPIENT format for PO. Consistent with previous studies (De Cuypere & Verbeke, Reference De Cuypere and Verbeke2013; Engel et al., Reference Engel, Grafmiller, Rosseel and Szmrecsanyi2022; Theijssen et al., Reference Theijssen, ten Bosch, Boves, Cranen and van Halteren2013; Wolk et al., Reference Wolk, Bresnan, Rosenbach and Szmrecsanyi2013), certain structures were excluded from our analysis (Table 2), as the factors that influence the choice between DO and PO constructions may differ from those underlying the operationally defined patterns described above. This limitation is acknowledged in the Discussion section, where we highlight the need for future research to extend the analysis to a broader range of dative-related phenomena. As part of our handling of learner errors, we considered learners’ apparent intended meaning when evaluating whether a particular pattern should be classified as either a DO or PO construction. For instance, the sentence we serve breakfast to seven thirty was not treated as a PO construction because it was interpreted that the learner intended to write we serve breakfast at seven thirty.

Table 2. Exclusion criteria for DO and PO constructions

Drawing on the existing literature (De Cuypere & Verbeke, Reference De Cuypere and Verbeke2013; Engel et al., Reference Engel, Grafmiller, Rosseel and Szmrecsanyi2022; Theijssen et al., Reference Theijssen, ten Bosch, Boves, Cranen and van Halteren2013; Wolk et al., Reference Wolk, Bresnan, Rosenbach and Szmrecsanyi2013), we initially identified 78 verbs that have been studied in the context of dative alternation (see Supplementary Appendix S1 for the list of the verbs). However, given the necessity of manual filtering and coding (detailed in the following section), it is important that the proportion of verb occurrences used in dative constructions is not exceedingly low. To manage the workload, we retained only verbs that appeared in at least one instance of either the DO or PO constructions among 10 randomly chosen examples of the verb’s use, ensuring a minimum occurrence rate of at least 10%. Additionally, to examine how learners’ proficiency levels interact with other predictor variables to influence their choice of dative constructions, it is essential for the target verbs to be well represented across different proficiency levels. Specifically, we excluded verbs that did not occur at least five times in each of three among the five CEFR levels (A1–C1).Footnote 5

All writings in EFCAMDAT were syntactically parsed through the Stanford unlexicalized constituency parser (Klein & Manning, Reference Klein and Manning2003), using the provided English model. Subsequently, we employed R scripts to retrieve the DO and PO constructions along with their themes and recipients within the parsed trees. While earlier studies have shown a reasonable level of accuracy in EFCAMDAT’s automated syntactic parsing (Geertzen et al., Reference Geertzen, Alexopoulou, Korhonen, Millar, Martin, Eddington, Henery, Miguel, Tseng, Tuninetti and Walter2014; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Murakami, Alexopoulou and Korhonen2018), this does not guarantee a similar level of accuracy in identifying DO and PO constructions. To specifically evaluate the accuracy of extracting these constructions, we calculated recall, defined as the proportion of the target structure correctly identified within the corpus, based on 20 manually verified occurrences of DO or PO constructions for each of the 28 verbs.Footnote 6 If a verb lacked any DO or PO constructions in a sample of 200 randomly chosen instances, or if fewer than 10 occurrences were identified among 1,000 instances, that verb was omitted from further analysis because of the impracticality of verifying its extraction accuracy. This criterion led to the exclusion of five verbs (allow, carry, get, read, take), leaving 23 target verbs: assign, assure, bring, cause, cost, deliver, give, guarantee, leave, lend, offer, owe, pay, present, promise, sell, send, serve, show, teach, tell, wish and write. The mean recall rate was 0.86 (SD = 0.08), indicating a relatively low rate of false negatives.

3.3. Manual check, animacy coding and other predictors

Although the recall rate was high, the dataset may still contain false positives (i.e., non-dative constructions identified as dative constructions) as well as segmentation errors in the automated identification of themes and recipients, that is, incorrect segments of text being identified as either a theme or recipient. To address these issues, three coders reviewed the automatically identified DO and PO constructions to (i) remove any cases erroneously identified as DO or PO, (ii) correct mistakes in the segmentation of themes and recipients and (iii) categorize each recipient based on animacy (animate vs. inanimate). The goal was to review at least 50 observations for each combination of the 23 verbs and the five CEFR levels. However, achieving this was not always feasible, as many combinations of verbs and CEFR levels had fewer than 50 instances. This, along with other factors such as variability in the number of excluded cases between verbs and differences in coding efficiency among coders, resulted in variation in the number of cases coded for each verb (see Figure 1A). Following this procedure, some errors persisted in the dataset. To further refine our data, two additional student helpers were enlisted to examine all cases, checking and correcting common errors such as the coding of DO versus PO and the segmentation of themes and recipients. Ultimately, our dataset comprises 5,785 cases, including 3,924 DO and 1,861 PO constructions. The dataset includes the 10 L1 groups mentioned in the Data section, with observations from L1 Brazilian-Portuguese and L1 Mandarin speakers together comprising approximately half (49.7%) of the total. This skew in the distribution of L1 groups largely stems from that found in the EFCAMDAT, which in turn reflects the institutional context in which the data were collected (Alexopoulou et al., Reference Alexopoulou, Meurers, Murakami, Ziegeler and González-Lloret2022). The number of words in the theme and recipient (i.e., NP length) was automatically calculated and the pronominality (whether they were pronouns) of these NPs was also determined automatically. For verb-specific DO preference, we used the proportion of DO constructions relative to both DO and PO constructions for each verb in the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies, Reference Davies2008) as a measure of verbs’ statistical distributional properties and referred to this proportion as the DO preference score. The idea is that if learners have acquired constructional preferences for individual verbs from the input, these preferences should be reflected in the distribution of DO and PO constructions in COCA. We employed the same algorithm for identifying DO and PO constructions in COCA as we used for EFCAMDAT. The mean recall rate for these retrievals, calculated in the same manner as in EFCAMDAT, was 0.82 (SD = 0.12), indicating a high level of accuracy. However, unlike EFCAMDAT, manually reviewing identified cases to filter out erroneously identified (false-positive) cases was impractical in COCA because of the large number of identified cases. Therefore, the approach we adopted was to calculate precision, defined as the proportion of true positives among all identified positives, in a sample and to use it to estimate the frequency of DO and PO constructions in COCA. For instance, if our algorithm identified 10,000 occurrences of a verb in the DO construction and the corresponding precision was 0.6, we estimated the frequency of the verb in the DO construction to be 6,000 (i.e., 10,000 × 0.6). We manually reviewed a random sequence of automatically identified cases until we encountered 20 true positives for each construction (DO and PO) of each verb, which allowed us to determine the number of false positives. From this, we derived precision (M = 0.59, SD = 0.27). This precision was then applied to estimate the frequency of DO and PO constructions for each verb, from which the statistical information of verbs was computed.

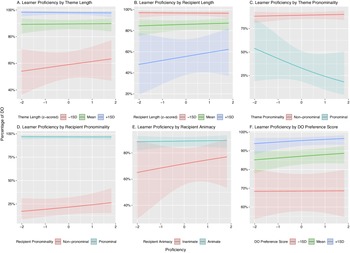

Figure 1. (A) Observation counts for DO and PO constructions across verbs. (B) DO construction proportions in relation to the theme’s length, the recipient’s length, and the DO preference score, presented across CEFR levels. Each dot represents a verb in the panels showing the DO preference score. Trend lines were derived from bivariate logistic regression models and grey bands illustrate the 95% confidence intervals. (C) Distribution of DO and PO constructions by recipient animacy and theme/recipient pronominality across CEFR levels. The numbers on the figure are observation counts reflecting the reliability.

3.4. Data analysis

To investigate the association between animacy, pronominality, NP length of themes and recipients and the selection of DO versus PO constructions in dative constructions, a series of mixed-effects logistic regression modeling was performed using lme4 package version 1.1-34 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2023) and R version 4.2.1, (R Core Team, 2022). The response variable was constructional selection (i.e., PO vs. DO) for the 23 verbs, with the PO construction as the reference category. The predictor variables included theme and recipient pronominality, theme and recipient length, recipient animacy, the proportion of DO in COCA and learner proficiency operationalized as the Englishtown level. Our focus was to examine the interaction between learner proficiency and the variables of interest, such as the varying impact of recipient animacy and theme length across proficiency levels. Given that adding all interaction terms to the model would result in a very complex model that would probably lead to convergence issues, we decided to build one model per focal predictor, such that a model involves one interaction term, to investigate whether and how the association between the predictor and constructional selection varies across learners’ proficiency levels. Crucially, while we focused on one interaction term per model to ensure convergence, all other key variables were included as covariates. This allowed us to assess the unique effect of each focal predictor while controlling for the influence of other factors. For example, when investigating whether the recipient being animate or inanimate plays a role in the use of DO and whether the influence differs depending on learner proficiency, an interaction term between learner proficiency and recipient animacy, as well as the main effects of both variables, was added to the model. All other variables (recipient length, theme length, theme pronominality, recipient pronominality and DO preference score) were added as covariates. The three categorical predictors (recipient animacy and theme/recipient pronominality) were sum-coded (−0.5/+0.5; inanimate and full NP = −0.5; animate and pronoun = +0.5), which centers factors at zero, so that the intercept is the grand mean and each binary coefficient reflects the difference between level means. Unlike traditional dummy coding (0/1), which sets one specific category as the baseline, sum-coding allows us to interpret the main effects as the average effect across all categories, ensuring more straightforward and intuitive interpretation of interaction terms. Quantitative predictors (recipient/theme length, DO preference score and proficiency level) were standardized around the grand mean (M = 0, SD = 1).

As random effects, we included random intercepts for the learners’ L1. In addition, we included random intercepts for the interaction between verbs and the topic of the essay because it is possible that certain combinations of verbs and dative constructions (e.g., DO) occur frequently in lessons leading up to the writing task in Englishtown or as part of the task prompt. This frequent exposure can prompt the use of these combinations, thereby increasing their frequency. We attempted to include random slopes as complex as allowed by the study design (Barr, Reference Barr2013). When convergence issues occurred, the model simplification procedure proposed by Bates et al. (Reference Bates, Kliegl, Vasishth and Baayen2015) was followed. First, we removed the correlation parameters among random components. If this did not resolve the issue, we checked the variance of the random effect components using the rePCA function from the lme4 package and removed the random effect components that demonstrated very small variance. Removing random effects with near-zero variance does not affect the fixed-effect estimates but avoids overfitting, thereby making the model more robust and interpretable. Once the simplified model converged, we reintroduced the correlation parameters into the simplified model and assessed which model was better by performing likelihood ratio tests. The alpha level for this likelihood ratio test was set to alpha = .20, following the recommendation of Matuschek et al. (Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017). When significant, the more complex model was selected as the final model. We did not disambiguate verbs by sense; fine-grained sense annotation is beyond the scope of the present study. Potential lemma-level bias arising from sense mixtures is conditioned on by the COCA-based DO-preference covariate and captured by the verb-by-topic random intercepts, which account for baseline selection tendencies and prompt/lesson exposure.

As a result of the model-selection procedure, we retained six separate GLMMs, each targeting a different focal predictor. To control for the family wise inflation of Type I error within each model, we applied both the Holm procedure (family wise error rate) and the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) procedure (false-discovery rate) to the full set of fixed-effect p-values; the adjusted values are presented in Supplementary Appendix S2 (Supplementary Tables S1–S6). Importantly, every main effect that reached significance in the raw analyses remained significant after either correction. For ease of reading, we therefore report the unadjusted p-values in the text, while directing readers to the Supplementary Material for the Holm- and BH-adjusted counterparts.

When the interaction term was significant, we re-referenced the continuous proficiency variable to identify the specific level at which the target factor became (non-)significant. To do this, we created a dummy variable for the proficiency level. For example, to investigate whether the variable of interest was significant at Englishtown level 1, we transformed the proficiency-level factor by subtracting 1 from each level, making level 1 the baseline (i.e., zero). In practical terms, this re-referencing tells us, for each proficiency level in turn, whether a given factor (e.g., animacy) significantly shifts the probability of choosing a DO construction at that particular level.

Next, we used the model_parameters function from the parameters package (Lüdecke et al., Reference Lüdecke, Ben-Shachar, Patil and Makowski2020) with parametric bootstrapping (B = 1000) to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the odds ratios (ORs) derived from the logistic regression model. When the 95% CI for an OR included 1, the effect was deemed not significant. For ease of interpretation, note that ORs reflect the effect of an increase in the predictor’s value: ORs above 1 indicate that higher values of a predictor increase the likelihood of choosing a DO construction, whereas ORs below 1 indicate the opposite pattern (i.e., a preference for PO).

However, simply examining the OR at each proficiency level does not clarify whether the proportion of DOs varies across proficiency levels within a specific category of a predictor variable (e.g., theme pronominality). Therefore, in addition to this level-by-level analysis, we conducted a slope analysis to determine whether the slope of the Englishtown proficiency level was significant at each level of the categorical factors.

To implement the slope analysis, we used a dummy variable in which one category level was recoded as the reference (i.e., set to zero). For instance, when examining the slope for pronoun themes, we recoded theme pronominality, so that “pronoun” was coded as zero; when examining the slope for non-pronoun themes, we recoded theme pronominality, so that “non-pronoun” was coded as zero. This approach enabled us to test whether the slope (i.e., the effect of Englishtown proficiency) was statistically significant within each category level.

For every GLMM, we assessed multicollinearity using check_collinearity function of the performance package (Lüdecke et al., Reference Lüdecke, Ben-Shachar, Patil, Waggoner and Makowski2021). As is typical with interaction specifications, models including interaction terms showed inflated VIFs for the interaction and proficiency indicators, whereas the main-effect predictors (pronominality, NP lengths, animacy, DO preference) exhibited low VIFs (all <5). Full collinearity tables, complete model outputs and the full replication package (corpus-processing scripts, analysis data and R code) are available in our OSF repository: https://osf.io/u845d.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive analysis

Figure 1 presents the counts of DO and PO constructions for each verb and illustrates the descriptive relationship between the main predictors and proportions of these constructions. Figure 1A shows that there were generally more DO than PO constructions in our dataset. Moreover, it reveals substantial variation in both the number of observations and the proportion of each construction across the 23 verbs. For instance, wish is predominantly used in DO constructions, whereas sell is more strongly associated with PO constructions, highlighting the importance of accounting for the differences between verbs in our analysis. Figure 1B shows that longer themes, shorter recipients and a higher proportion of DO usage in COCA are each correlated with a higher proportion of DO constructions in EFCAMDAT. Although this pattern is consistent across different proficiency levels for theme and recipient length, the association with the DO preference score appears to intensify at higher CEFR levels, as evidenced by the lower predicted DO proportion in the lower DO preference score spectrum within these levels. Nonetheless, these trends appear to be generally consistent across all CEFR levels, suggesting that these factors affect the selection of dative constructions by L2 learners from the early stages of L2 acquisition.

Figure 1C demonstrates that the animacy of the recipient, along with the pronominality of both the theme and recipient, is associated with learners’ selection of dative constructions. It shows that when the recipient is animate, DO constructions are chosen in approximately 75% of instances, whereas inanimate recipients lead to PO constructions in 90% of the instances. In cases where the theme is a pronoun, PO constructions account for nearly 90% of occurrences, whereas non-pronominal themes result in approximately 70% being DO constructions. Additionally, a pronominal recipient correlated with the use of DO constructions in 93% of cases, in contrast to 86% for PO constructions when the recipient was not a pronoun. These tendencies appear consistent across CEFR levels, suggesting that these factors play a role in construction selection early in L2 acquisition.Footnote 7 We now turn to mixed-effects modeling to examine the associations between the predictors and constructional preferences more formally, including the predictors’ interactions with Englishtown levels, while controlling for the effects of the other predictors.

4.2. Generalized linear mixed-effects regression modeling

4.2.1. Theme length

The final theme length model found no interaction between learner proficiency and theme length (Estimate = −0.09, SE = 0.15, z = −0.59, p = .557, OR = 0.92). The main effect of theme length was significant (Estimate = 1.78, SE = 0.17, z = 10.28, p < .001, OR = 5.96); the longer the theme, the more likely learners prefer DO. Figure 2A illustrates this tendency.

Figure 2. Interaction effects of learner proficiency with six predictor variables on the probability of choosing a direct-object (DO) over a prepositional-object (PO) dative construction. (A) Theme-NP length; (B) Recipient-NP length; (C) Theme pronominality; (D) Recipient pronominality; (E) Recipient animacy; (F) Verb-specific DO-preference score in COCA. For continuous predictors (A, B, F) the green line shows the effect at the grand mean, while red and blue lines represent −1 SD and + 1 SD from the mean, respectively; shaded ribbons show 95% confidence intervals. For categorical predictors (C–E) red = non-pronoun/inanimate, blue = pronoun/animate. The y-axis depicts predicted DO proportion; the x-axis is the centered-and-scaled Englishtown proficiency level (1–15)

4.2.2. Recipient length

The final model of recipient length found no interaction between learner proficiency and recipient length (Estimate = 0.10, SE = 0.17, z = 0.58, p = .561, OR = 1.10). The main effect of recipient length was significant (Estimate = −1.59, SE = 0.29, z = −5.50, p < .001, OR = 0.20); when the recipient is shorter, learners prefer to use DOs. Figure 2B illustrates this tendency.Footnote 8

4.2.3. Theme pronominality

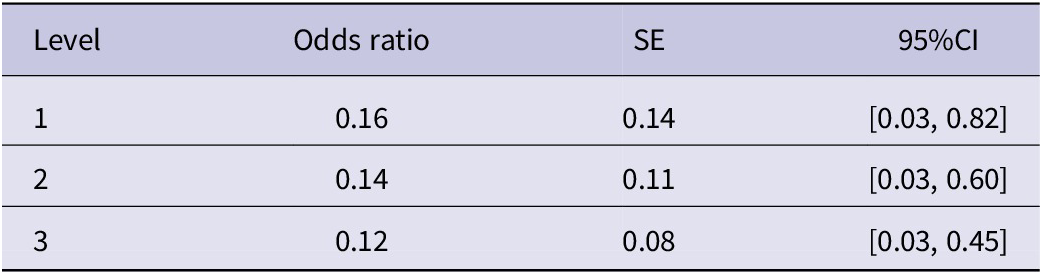

The final model found no significant interaction between learner proficiency and theme pronominality (Estimate = −0.49, SE = 0.40, z = −1.21, p = .225, OR = 0.62). As can be seen in Figure 2C, the 95% CI overlap for lower-level learners, indicating that they use DO to the same extent whether the theme is a pronoun or not. By contrast, more proficient learners were less likely to use DO when the theme was pronouns. Although the interaction term was not significant, we further investigated the interaction by calculating the 95% CI of the ORs at the lower Englishtown levels and examined whether there was a significant difference in the use of DO between when the theme was a pronoun and when it was not. Table 3 summarizes the ORs and 95% CIs. Even low A1 to mid A1 learners (levels 1 and 2) were less likely to use DO when the theme was a pronoun. Another notable observation from Figure 2C is that the blue line (when the theme is a pronoun) shows a steady decline as proficiency increases. To investigate this tendency, theme pronominality was re-coded as a dummy variable and new GLMMs were built. The results of this analysis indicate that neither model showed a statistically significant effect of learner proficiency (Pronoun: Estimate = −0.45, SE = 0.34, z = −1.33, p = .184, OR = 0.63; Non-Pronoun: Estimate = 0.07, SE = 0.08, z = 0.91, p = .365, OR = 1.08). Therefore, it can be concluded that learner proficiency might not influence the use of DO, regardless of whether the theme is a pronoun.

Table 3. Summary of odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for the effect of theme pronominality

Note: The 95% CIs were calculated using the parametric bootstrapping method with model_parameters function (iterations = 1,000).

4.2.4. Recipient pronominality

As can be seen in Figure 2D, the final model of recipient pronominality did not find an interaction between learner proficiency and the pronominality of the recipient (Estimate = −0.16, SE = 0.21, z = −0.80, p = .422, OR = 0.85). The main effect of recipient pronominality was significant (Estimate = 4.68, SE = 0.44, z = 10.64, p < .001, OR = 107.79); when the recipient was a pronoun, the DO structure was preferred regardless of learner proficiency.

4.2.5. Recipient animacy

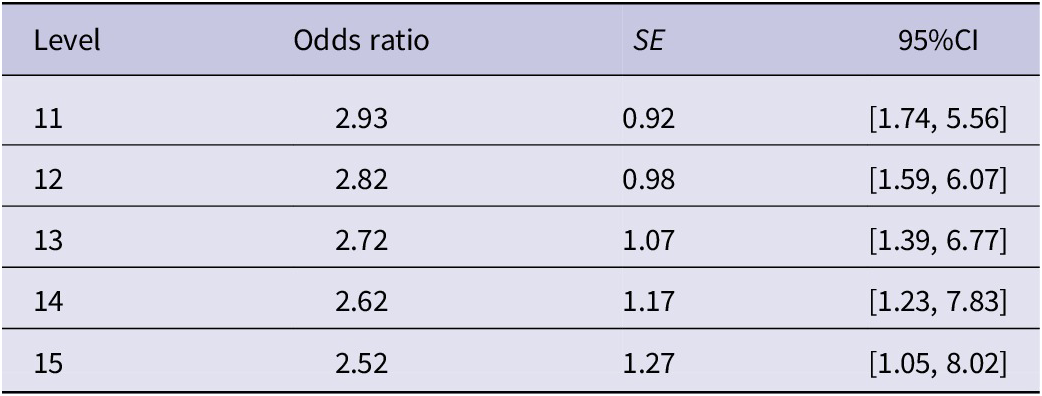

The final model of recipient animacy did not find an interaction between learner proficiency and recipient animacy (Estimate = −0.13, SE = 0.27, z = −0.46, p = .645, OR = 0.88). The main effect of recipient animacy was significant (Estimate = 1.17, SE = 0.31, z = 3.78, p < .001, OR = 3.21), and it appears that regardless of proficiency, learners were likely to prefer DO when the recipient was an animate noun. Although Figure 2E seems to indicate that higher-level learners did not show a discrepancy in the use of DO based on whether the recipient was animate or inanimate, this was not confirmed by the 95% CIs of the ORs for higher-level learners. Table 4 summarizes the effects of recipient animacy at levels 11–15. The ORs were relatively consistent, decreasing from 2.93 to 2.52 as levels increase. Notably, the 95% CIs did not include one at these levels, suggesting that the animacy effect was maintained. In short, the relationship between recipient animacy and the percentage of DO was consistent from the beginner to the advanced levels.

Table 4. Summary of odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for the effect of recipient animacy

Note: The 95% CIs and p-values were calculated using the parametric bootstrapping method with model_parameters function (iterations = 1000).

Figure 2E also indicates a steady increase in DO use when the recipient is inanimate as proficiency increases (see the red line). However, a separate analysis using dummy variables did not confirm this tendency (Estimate = 0.12; SE = 0.26; z = 0.45; p = .651, OR = 1.12).

4.2.6. DO preference score

The final model did not find any interaction between learners’ proficiency and the COCA-based DO preference score (Estimate = 0.08, SE = 0.08, z = 0.93, p = .354, OR = 1.08). The main effect of the DO preference score was significant (Estimate = 1.13, SE = 0.18, z = 6.34, p < .001, OR = 3.10); if a verb is commonly used in a DO in COCA, it is also likely to be used as a DO in EFCAMDAT. This tendency was not moderated by learner proficiency, thus suggesting that input frequency is influential across learners’ proficiency levels (Figure 2F).

5. Discussion

This corpus study investigated the developmental stage at which learners were able to use the factors for selecting dative alternation. Our key findings are summarized as follows. First, neither theme nor recipient length showed a clear interaction with proficiency, but both lengths were clearly associated with the DO proportion overall, implying that this information was used across developmental stages. Based on previous studies, we predicted that theme and recipient length could be used from the early stages of learning as their influence stems from language-independent processing strategies. These results are consistent with our hypothesis.

Second, based on previous studies, we predicted that pronominality would begin to be used for syntactic selection from the intermediate level. However, our results show that it can be used from a much earlier stage, such as low A1, for both theme and recipient pronominality. There are some differences between Marefat’s (Reference Marefat2005) study that our prediction was based on and ours. Marefat conducted an experiment in which learners were asked the question, What did you give to Mary? The aim was to determine whether the participants would respond with I gave a book to Mary (new-given order of information) or I gave Mary a book (given-new order). This differs in format from the free production task underlying the corpus data used in the present study, which may have influenced the differences in the results.

Third, we expected that using animacy information would be challenging for learners until they reached an advanced level, at which point they would come to understand the construals hidden in the constructions. Nonetheless, we found that even low-proficiency learners were sensitive to the animacy information of the recipient and preferred the DO when the recipient was animate. This result suggests that, from the initial stage observed in the present study, learners understand the correspondence between constructions and their construals. These results contradict the findings of Xiang and Chang (Reference Xiang and Chang2023) and Xiang et al. (Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024), who showed that only highly proficient learners are sensitive to recipient animacy. We speculate that the contradiction between the results of the previous studies and ours was due to a task-dependent effect. Both previous studies employed acceptability judgment tasks. The recipient is often animate whereas the theme is often inanimate, and projecting the cognitive bias that more animate participants deserve more prominent syntactic positions (Langacker, Reference Langacker1986; Pinker, Reference Pinker1989) leads learners to choose the DO when the recipient is animate, because that construction places the recipient immediately after the verb: The PO, by contrast, pushes the same recipient into a less prominent prepositional slot. Conversely, when the recipient is inanimate, no animacy‑based pressure to promote it exists, so learners do not show the same DO preference. Because production simply requires selecting the form that aligns with this prominence bias, the animacy effect surfaces even at low proficiency, whereas the same knowledge can remain undetected in reception tasks that require explicit rejection of less probable forms.

Fourth, perhaps most notably, statistical information of verbs based on native-speaker corpora (COCA) was a significant predictor of learner behavior from early proficiency levels. In other words, from the early stages of learning, learners produced language in line with the statistical distributions observed in native speakers, regarding how frequently each verb occurs in the DO and PO constructions. According to the previous studies based on judgment task, it is unlikely that such information is used in the early stages of L2 learning (cf., Xiang & Chang, Reference Xiang and Chang2023; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024). We speculate that this was also due to task-dependent effects. Studies on unconscious L2 knowledge have shown that learners’ grammaticality judgments are only slightly higher than the chance rate when their proficiency is low, because their knowledge at this stage is too underspecified to enable them to reject ungrammatical sentences (e.g., Rebuschat & Williams, Reference Rebuschat and Williams2012; Tao & Williams, Reference Tao and Williams2018; Williams, Reference Williams2005; Williams & Kuribara, Reference Williams and Kuribara2008). With this state of weak knowledge, it is likely to be difficult for learners to accurately assess the acceptability of dative alternation, because it is confounded by a variety of factors, as explained in this article. The fact that the learners were nevertheless sensitive to the statistical information from the early stages of development requires us to consider what they rely on to construct sentences without having access to fully developed and robust linguistic knowledge.

One possible interpretation is that this reflects a form of cognitive bias shared across humans. Studies, such as Saldana et al. (Reference Saldana, Oseki and Culbertson2021), Culbertson and Adger (Reference Culbertson and Adger2014) and Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Adger, Abels, Kanampiu and Culbertson2024), which sought causal explanations for typological universals of language (e.g., Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1957), have shown that novice learners tend to reconstruct untrained word orders in accordance with cognitive biases. These studies suggest that humans acquire grammar by making use of not only the statistical properties of the input but also the cognitive biases that shape which grammatical systems are more naturally learnable for them. In the case of dative alternation as well, universal correspondences between semantic structure and argument structure have been repeatedly noted (e.g., Pinker, Reference Pinker1989, Reference Pinker2007). The early emergence of verb-specific preferences observed in the present study may likewise reflect a cognitive bias that maps conceptual structures onto L2 constructions, rather than mere statistical learning.

At the same time, previous studies employing comprehension-based tasks have demonstrated that learners come to rely increasingly on animacy, pronominality and statistical information of verbs as their proficiency develops. Taken together, these findings suggest that learners’ knowledge of dative alternation becomes gradually reinforced and refined through linguistic experience. The absence of significant interactions with proficiency in our data should therefore not be interpreted as indicating a lack of developmental change. As Pinker (Reference Pinker2007) notes, while the conceptual structure and argument structure of dative constructions exhibit certain cross-linguistic regularities, they also display language-specific realizations. It is plausible that cognitive biases are reflected early in production, and that these biases develop into more stable and integrated interlanguage knowledge, and eventually surface in comprehension tasks as Xiang et al. (Reference Xiang, Wei and Chen2024) have shown. Importantly, this should not be simply taken to mean that L2 learners produce native-like sentences from the beginning. Rather, when examined in terms of overall distributional tendencies without focusing on specific L1 backgrounds, the learner data exhibit patterns that align with those found in native-speaker corpora.

In any case, the present findings provide an interesting perspective for exploring the similarities and differences between L1 and L2 learning mechanisms. In L1 research, overgeneralization and the subsequent immediate retreat from overgeneralization have been discussed as universal tendencies. In contrast, previous studies showed that L2 learning appears to involve a more gradual process, in which learners progressively expand the range of information they can exploit as their proficiency increases. A particularly noteworthy contribution of the present production data is that even low-proficiency learners produced distributions resembling those of native speakers, which presents a theoretically interesting contrast to L1 acquisition, where developmental discussions are also typically based on production data, as well as to studies of L2 comprehension showing gradual development. Future research should investigate how L2 learners integrate input frequency, conceptual structure and general processing mechanisms, and how the relative contribution of these factors may vary across modalities.

This study has some limitations. First, although the present study reports findings from a large-scale corpus analysis, it is based on a single corpus and covers only one modality. Therefore, the extent to which these results have external validity remains to be determined. Future research should verify the generalizability of the present findings through analyses of multiple corpora and complementary experimental investigations. Second, the difficulty of distinguishing Recipients from Locatives when the post-to NP is inanimate must be acknowledged. As Langacker (Reference Langacker1986) and subsequent work suggest, such cases lie on a continuum and resist a categorical distinction. Previous corpus-based studies on the dative alternation do not explain the difference between the two, yet they claim to have excluded locatives. We followed their practice when instructing our coders to remove locatives (among other non-DO and non-PO cases). Third, although this study was conducted on dative alternation, other alternation phenomena (e.g., locative alternation, transitive alternation) need to be investigated to fully justify the discussion developed in this article. In addition, the present study focused only on the most typical types of dative alternations (e.g., benefactives like She bought a house for her fiancé. were excluded from the analysis). In the future, it will be necessary to examine whether similar results can be observed for various related phenomena. Finally, as one anonymous reviewer noted, our analyses operate at the lemma level rather than the sense level. Consequently, sense‐specific differences in DO/PO preferences (Bresnan & Ford, Reference Bresnan and Ford2010) may be conflated in the lemma‐level estimates. Our models condition on lemma‐level baselines (via the COCA-based DO preference covariate and verb-by-topic random intercepts), but these controls cannot fully substitute for sense annotation. Manual sense annotation for all tokens is beyond the scope of the present study; future work could use targeted sense annotation or sense-tagged resources to assess whether learners are sensitive to sense-level biases.

6. Conclusion

This study explored the dynamics of dative construction selection among L2 English learners across varying proficiency levels. Previous studies have led us to predict that construction selection is influenced by the length of noun phrases, pronominality, animacy, as well as statistical information at the verb level, and that these factors interact with proficiency levels. The present study showed that these effects are somewhat different from those observed in previous receptive processing studies. These findings enrich our understanding of L2 learners’ choice of dative constructions and provide implications for studies of the L2 learnability problem. Further research to test the hypotheses of this study will help elucidate human cognition in general through second language research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728925100965.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Shigenori Wakabayashi (Chuo University) for his valuable advice regarding data interpretation. We are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments, which helped improve the manuscript. All remaining errors are solely ours.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in OSF at: https://osf.io/u845d.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.