In March 1894, American labor leader Eugene V. Debs was fretting about discord within the movement. The source of the conflict was the American Protective Association (A.P.A.), a popular anti-Catholic fraternal organization that had been founded seven years earlier. Writing in the Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine, which he edited, Debs blamed the A.P.A.’s “naked bigotry” for inciting division within the labor movement. Debs wrote that its “sole object was to arouse dissensions in the ranks of organized labor” for the benefit of railroad corporations. He even cited unspecified evidence that suggested railroad companies had created the A.P.A., “two or three years ago,” as a means to blunt labor’s collective power. Labor disunity would easily enable the railroads to decrease wages and increase profits. “We write to warn organizations of railroad employees against the infamous purposes of the A.P.A.,” Debs proclaimed. “We write to tell them that once introduced into the organization their power to accomplish good for themselves forever vanishes.”Footnote 1

William Traynor, the A.P.A.’s Supreme President and editor of the Patriotic American, was outraged by the allegation that his order was colluding with railroad companies to drive down working-class wages. Debs had shown himself to be an “ignoramus,” Traynor wrote. First, he was mistaken on the timeline. The A.P.A. had been founded in 1887 by Henry Bowers, not “[b]etween two and three years ago.” More importantly, though, Traynor argued that the railroads were hostile to the A.P.A. He claimed that the railroads had fired “large numbers of men, known to be members of the A.P.A. … on account of their affiliations.” Thus, it made no sense that the A.P.A. had been the brainchild of the reprehensible railroads.

Moreover, if A.P.A. members were indeed the railroad’s hired guns, why would they be so poorly paid? The Supreme President contrasted the precarious financial position of his members with that of well-known labor leaders like Debs. “While there is not a labor leader of the A. P. A. who is not considerably poorer today than when he joined the order,” Traynor retorted, “many of the labor leaders who ten years ago were not worth ten dollars are today the owners of real estate and personal property which may be expressed in six figures.” Modest income among the A.P.A. membership was a point of pride for Traynor. It confirmed that the organization had not been corrupted by politics or corporate interests. He boasted that his organization had “not one millionaire, or a member of any trust, so far as we have been able to ascertain.” Instead, the A.P.A. derived its strength from “the large membership which the order has among the most intelligent of the members of labor organizations.” For Traynor, Debs’s allegation that the A.P.A. fought against American workers was particularly infuriating because the Supreme President considered the A.P.A. to be indispensable in the fight against corporate capital. Traynor could only conclude that Debs was “a romanist” – the standard epithet that A.P.A. members attached to anyone who criticized the order – and he further claimed that Debs feared the A.P.A. because it was “a standing menace to Irish Roman catholic supremacy in our grand labor organizations.” The A.P.A., in Traynor’s mind, was the true hero of the U.S. labor movement.Footnote 2

For Traynor and many nineteenth-century Americans, religion and political economy were closely intertwined. This ideological convergence shaped political and economic reform efforts throughout the Gilded Age, including the era’s working-class movements. The nineteenth century’s most prominent labor organizations, like the Knights of Labor, were part of a broader anti-monopoly movement at the turn of the century. The anti-monopoly movement was diverse, but anti-monopoly reformers generally believed that the dangerous classes, both above and below, threatened working-class social mobility and economic independence. Religious bigotries, though, often dictated which people and institutions were considered economically dangerous. Indeed, as anti-Catholic stereotypes collided with emergent anti-monopoly critiques in the late nineteenth century, some anti-monopoly reformers, I argue, came to see Catholicism as incompatible with traditional notions of free labor. Animated by this idea, these reformers embraced anti-Catholic politics and, in many cases, chose to establish, join, or support the A.P.A. Many in the A.P.A. thought Catholic workers lacked the autonomy necessary to be free laborers, leading to intra-union conflict and a distrust of labor organizations with significant Catholic membership. They also charged that the Catholic Church itself opposed free labor and was already profiting from slave labor in institutions like the Houses of the Good Shepherd, a charitable institution that sought to reform “abandoned women.”Footnote 3 Ultimately, the A.P.A. and its anti-Catholic bigotries contributed to the fragmentation of the working class in Gilded Age America in ways that scholars have not recognized.

While Eric Foner, Amy Dru Stanley, and other historians have compellingly shown how race and gender shaped nineteenth-century free labor ideology, the links between religious bigotry, free labor, and economic reform are underexplored.Footnote 4 Furthermore, histories of the Knights of Labor rarely, if ever, mention the A.P.A.Footnote 5 These connections, however, are crucial to understanding the full scope of social and cultural divisions that plagued working-class movements when trying to build coalitions adequately broad to succeed at the ballot box. Histories of the A.P.A. also have neglected issues of political economy in favor of electoral politics, school controversies, and immigration restriction.Footnote 6 And yet A.P.A. members often spoke and wrote about industrial capitalism and labor-capital conflicts. As William Traynor boasted and Eugene Debs lamented, A.P.A. members belonged to labor unions and prominent working-class organizations, such as the Knights of Labor. In fact, a group of Knights and Knights-sympathizers founded the A.P.A. in 1887. These labor-minded members of the A.P.A. claimed that corporations and aggregated capital prevented social mobility and economic independence for working-class Americans, violating deeply held values of free labor. In many ways, the A.P.A. sounded like a typical nineteenth-century labor organization.

What differentiated the A.P.A. from other working-class groups was its strident anti-Catholicism. Bigoted stereotypes of greedy bishops and their subservient Catholic hordes had haunted the American Protestant imagination since the colonial era.Footnote 7 The A.P.A. both inherited these older stereotypes and applied them to their new social and economic realities. The specter of docile and obedient Catholics seemed particularly threatening amid the widespread labor conflict and increasing economic inequality of Gilded Age America. The A.P.A., though, showed no interest in understanding the complex intra-Catholic debates about labor, capitalism, and the Social Question.Footnote 8 The A.P.A. instead sought to oust Catholics from labor organizations because they believed large Catholic memberships would allow the Church hierarchy to co-opt the votes of groups like the Knights of Labor for the purposes of personal profit and political power. The anti-Catholic organization also demanded public inspection of Catholic charitable institutions, specifically Houses of the Good Shepherd, in an effort to expose their purported slavelike labor regimes. Ultimately, the A.P.A. did not wish to undermine the labor movement, as Debs suggested, but to purify it of those whom they alleged fell short of American free labor ideals. By examining the A.P.A.’s anxieties about Catholicism and labor, we can more fully comprehend the limits of working-class economic and political movements in the Gilded Age.

The Anti-Monopoly Origins of the A.P.A

Henry F. Bowers and several associates established the A.P.A. in March 1887. Though the A.P.A. did not begin to influence electoral politics until the 1890s, the organization’s founding years are vital to understanding the A.P.A. and its relationship to Gilded Age economic reform movements.Footnote 9 Bowers and the other A.P.A. founders were anti-monopoly men. They either belonged to the local Knights of Labor assembly or were supportive of its efforts to wrest political control from the business elite in Clinton, Iowa.Footnote 10 The A.P.A.’s beginnings concretely demonstrate how prejudicial fears of Catholicism and particular real-world events could combine to push some labor-minded reformers to incorporate anti-Catholic politics into their free labor ideologies.

When the Knights of Labor reached its zenith in 1886, the United States already had transitioned from a land of yeoman farmers, skilled artisans, and chattel slavery to one where wage labor predominated.Footnote 11 A large number of working-class Americans, including organizations such as the Knights of Labor, opposed the wage labor system because it conflicted with traditional proprietary-producer notions of economic independence.Footnote 12 Farmers, laborers, artisans, and small businessmen understood themselves to be “producers” – honorable workers who created the nation’s wealth through their sweat and skill.Footnote 13 As producers, nineteenth-century men expected opportunities to support a family without working for other people, something known as a “competence.”Footnote 14 A competence presumed gendered ownership of both land and self: a man fully owning his labor, the labor of his family, and the fruits of that labor. A competence, in turn, meant a man was economically independent enough to participate in a democracy.

By contrast, permanent wage labor signaled dependency. A wage-earning man owned neither the means of production nor reaped the full fruits of his labor.Footnote 15 He was subordinate to his employer, threatening to put him at the same social level as other dependents: women, children, and slaves.Footnote 16 Since economic independence conferred political legitimacy, a perpetual proletariat seemed to threaten the foundations of the American political system. Contemporaries called the nationwide debates about the dangerous consequences of proletarianization, as well as what should or could be done about it, “the Labor Question.”Footnote 17

The Knights of Labor embraced the language of producerism and fought against the wage labor system. Formed in 1869, the group claimed a membership of more than 750,000 members by 1886, when the Knights were striking against Jay Gould’s railroads. Historian Leon Fink has called it “the first mass organization of the American working class.”Footnote 18 While not wholly opposed to capitalism or profit, the Knights contended that labor should not be governed by market forces. The increasing power of capitalists and the downward pressure from more competition, both from a nationalizing market and increased immigration, ensured that working people could not freely negotiate a contract. A starving man was in no position to negotiate fair wages. The Knights argued that workers deserved a “proper share of the wealth” they created; anything else resulted in dependence. Linking economic and political independence, the Knights claimed that there was “an inevitable and irresistible conflict between the wage-system of labor and republican system of government.”Footnote 19 While the labor organization was not monolithic, the Knights often touted “cooperation,” or cooperatives, as a way to secure workers the full fruits of their labor and to end capital-labor conflicts. Through cooperation, working-class men could reclaim their economic and political independence, strengthening American democracy.Footnote 20

In 1886, a year before founding the A.P.A., Henry Bowers wrote to a newspaper editor to praise the cooperative system. The prevailing wage-labor system was so inherently unstable in Bowers’s mind that, in his words, “sooner or later, the co-operative system … will be the basis of all manufactures of this country.” This prediction was not based on mere conjecture. Bowers lived in Clinton, Iowa, but he claimed to have seen the cooperative system in action when visiting an Ohio glass factory. The factory had a “co-operative congress of laborers and capital” that collectively determined what percentage of the end product’s price would go to the various workers, from the blowers to the warehousemen to the general manager. If the price of glass increased, the workers proportionately benefited; if the price of glass declined, the workers suffered accordingly. As such, Bowers declared that “every man is virtually working for himself and needs no other stimulus to urge him to duty than the fact that he is his own master, working for his own good.” These glass workers in Ohio were not “the human industrial slaves of a mercenary, grasping corporation,” like most nineteenth-century factory workers. They retained their self-ownership and independence. Bowers’s description of a cooperative system aligned him with mainstream Knights of Labor thought, which tried to reimagine the proprietary-producer model of independence for the industrial world.Footnote 21

Always involved in politics, Bowers backed a man named Arnold Walliker for Clinton’s mayor in 1886. Walliker had joined the local Knights assembly that year, but not without controversy. Walliker was a lawyer, and the Knights did not consider lawyers to be part of the producer class and so denied them membership. General Master Workman Terence Powderly threatened to expel the organizer of the Clinton Knights for accepting Walliker into their assembly in defiance of the rules. However, Powderly later backed down when 500 members of the local assembly not only voiced their support for Walliker’s membership but also his candidacy for mayor. Walliker was a reform-minded labor agitator, and the Clinton Knights, many of whom were Irish Catholics, thrust him to victory in the 1886 mayoral election on a Knights of Labor ticket. The first-time politician was one of many Knights-supported candidates who won local elections throughout the country in 1886, the year when the Knights made their strongest push for political power. Walliker pursued his reform agenda during his tenure, raising taxes on large companies and striving to break up local monopolies. Through Walliker, the Clinton Knights had obtained political power and appeared to be brandishing it.Footnote 22

The situation took a sudden turn when Arnold Walliker suffered a surprising defeat after running for reelection in 1887. Local business leaders and community elites branded the incumbent mayor as an anarchist and dangerous radical, but Walliker and his supporters had anticipated those attacks. They did not expect, however, the town’s Irish-Catholic laborers to abandon Walliker at the polls, which they did by over 20 percentage points in a notoriously Irish ward. Walliker could not overcome that electoral shift. The now-outgoing mayor and his allies sought answers as to why the Irish-Catholic laborers, many of whom were presumably Knights, switched allegiances. Walliker, Henry Bowers, and others blamed the local Irish-Catholic priest at St. Mary’s Catholic Church, Father E. J. McLaughlin. McLaughlin allegedly pressured his parishioners into voting for Walliker’s opponent. Although it is unclear whether he ever advocated for either candidate, any rumored clerical interference in elections revived longstanding fears that many Americans held about the Catholic Church’s proclivity for political manipulation. By 1887, religious fault lines had started to show within the Knights of Labor in Clinton, and it would become a problem throughout the United States.Footnote 23

The Knights largely owed their size and political effectiveness to Catholics. In fact, the group’s leadership estimated that Catholics made up 50 percent of the Knights of Labor by the early 1880s, and a large proportion of them were Irish. One famous study of the Knights in Rutland, Vermont, showed that support of a sympathetic Irish-Catholic priest could lead to rapid growth of a local Knights assembly. Irish Catholics also held key leadership positions within the Knights at the height of their influence. This included the most prominent member of the Knights, Terence Powderly, who became Grand Master Workman (later General Master Workman) of the order in 1879. The Catholicity of the Knights and Powderly himself would both positively and negatively affect the labor group from its peak through its ultimate decline.Footnote 24

Anti-Catholicism occasionally divided the Knights in the 1880s and early 1890s. This religious split could appear in votes at the assembly level; however, Terence Powderly served as the most common target. Some Protestant and non-religious Knights branded Powderly as an agent of the papacy, loyal to the powers in Rome and not to the American worker. When visiting Denver in 1889, Powderly was asked, “Is it not a fact that you attend mass, sometimes as often as three times a day; that you fully confess even the secrets of the order to the Catholic priesthood, and that you are pledged to them to bend this order as they may wish to break it?”Footnote 25 This allegation became the most common anti-Catholic attack against Catholics in the Knights of Labor. Skeptics claimed that neither Powderly, priests, nor Catholic laborers supported the Knights or became members because they wanted to fight for the producing classes or American democracy. Instead, the Catholic Church supposedly used its legions of parishioners as a means to co-opt the Knights. This virtual takeover would allow Catholic leaders to wield the political might of the Knights of Labor for their material benefit. This charge relied on a very specific, and inaccurate, understanding of Catholicism and independence. Producerism preached that democracy and a healthy capitalist economy required self-ownership and independence, and political experiences with the Knights convinced some people that Catholicism and producerism did not mix.

For Henry Bowers, Walliker’s unsuccessful reelection campaign proved that Catholics could not be trusted in the anti-monopoly fight. Father McLaughlin and the Catholic Church had tipped their hands in Clinton. The Church had no interest in alleviating the plight of the industrial producer. Catholics had joined the Clinton Knights, with the support of the hierarchy, solely as a means to co-opt the labor organization for Catholicism’s political and economic advantage. Crucially, Bowers already harbored a deep sense of personal betrayal by Catholics and the Church. He blamed his lack of formal schooling as a child in Baltimore on the local Catholic Church. Bowers had long claimed – falsely – that the Church had shut down many public schools in Baltimore. Bowers thus believed common anti-Catholic stereotypes about power and dependence, and he readily attributed Walliker’s particular political failures to the Catholic Church.Footnote 26

Following the election, Bowers gathered Arnold Walliker and a small group of men in his office on Sunday, March 13, 1887. They formed an organization that would combat all forms of Catholic economic and political power in the United States. The men called it the American Protective Association. The A.P.A. was nonpartisan, both officially and in practice. Bowers was a lifelong Republican, while one of the other founders, Arnold Walliker’s older brother, Jacob, had previously run for office as a Democrat. Anti-monopoly ideals and anti-Catholicism, as opposed to party allegiances, brought these men together. The founders of the A.P.A. had partnered with Irish-Catholic workers in Clinton in a genuine attempt to form a nonpartisan, interdenominational working-class coalition. However, after the Irish-Catholic Knights broke ranks, Bowers and his colleagues turned their backs on the prospects of interdenominational cooperation.Footnote 27

The men in Clinton, Iowa, were not the only disaffected Knights to join the A.P.A. J. S. Hatfield, a man who was once A.P.A. State President of Nebraska, began working in 1883 as a head miller in Sedalia, Missouri. Like many, he joined a local labor organization and got involved in politics. The young man ran for alderman as a labor-friendly Republican but ultimately lost to the Democrat. It served as an awakening in Hatfield’s adult life. The American, a prominent Nebraska A.P.A. newspaper, wrote that Hatfield finally discovered “that the Roman Catholic church was in politics.” The most radicalizing moment, however, occurred in 1886. While a member of the Knights of Labor, Hatfield supposedly discovered from Terence Powderly and other Knights leaders that the organization needed to abide by the wishes of the Catholic Church. The American explained how Hatfield “learned that independent and liberty loving Protestants had nothing to expect from the Knights of Labor unless they first conformed to the wishes of the local priest.” This revelation outraged “some twenty or thirty Protestant laborers,” including Hatfield, who all considered forming a Protestants-only labor union in response. A year later, Hatfield moved to Columbus, Nebraska, and he became a charter member of Council No. 7 in 1891. He quickly moved up the state ranks and won the election for state president in April 1893. The newspaper boasted how Hatfield’s leadership helped inspire “a phenominal [sic] growth of the A.P.A. in Nebraska and adjoining states.”Footnote 28

Accuracy aside, this portrayal of Hatfield’s adulthood made for a compelling narrative. As the American chronicled it, Hatfield’s journey from hardworking miller to state president passed directly through the labor movement and the Knights of Labor. Ignoring anxieties about race, immigration, the saloon, and schools – though those topics could be found elsewhere in the newspaper – the article emphasized that Hatfield became an anti-Catholic radical because he was “so cruelly deceived in the K of L,” much like Bowers and the other founders.Footnote 29 The Knights remained so intertwined with early A.P.A. leaders that even as late as 1891, William Traynor continued to include articles from Knights of Labor periodicals in the Patriotic American. Footnote 30 In other words, both the American and Traynor understood that a combination of working-class politics and anti-Catholicism appealed to existing or potential A.P.A. members.

The Knights of Labor, indeed, may have been “the first mass organization of the American working class,” but some Knights increasingly began to question who belonged in that working class.Footnote 31 Who possessed the necessary qualities to be an economic citizen in the American industrial economy? For Henry Bowers, Arnold Walliker, and other important A.P.A. members, their vision of economic citizenship became tied to religion. Their individual experiences with the Knights of Labor strengthened those links. Catholics in the Clinton Knights supposedly had laid bare their dependent nature when they abandoned Walliker, a fellow Knight, at the demand of the local priest. Such obedience convinced many A.P.A. members that Catholic workers could not be trusted in the labor movement. After all, when push came to shove, they had shown that their loyalties resided with the Church, not the Knights or any other labor union. The Catholic Church and Catholic workers needed to be removed from labor organizations for the movement to have any chance of success. Many A.P.A. members took it upon themselves to begin that purge.

Purifying the Labor Movement

After Eugene Debs originally condemned the A.P.A. in the Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine in March 1894, a flood of hate mail landed on the labor leader’s desk. Numerous letters demanded that Debs retract his article, with one man even threatening assassination. But Debs stood firm. He doubled down with another article the following month and explained: “We care nothing about the A.P.A. except in so far as it is forced into labor organizations, is made to set brother against another, divide the membership, destroy the strength that unity confers, and reduce the whole mass of workingmen to the insufferable level of slaves.” Debs stressed that, unchecked, the A.P.A. and anti-Catholic bigotry would undermine working-class solidarity and destroy the entire U.S. labor movement. The plutocrats, he said, “have too much sense to be divided upon any such proposition.” Debs pleaded for workers to put aside anti-Catholic prejudices and focus on labor’s common foe. He claimed that only the “poor devils who are already half starved and more than half enslaved” would waste time fighting among themselves over something as trivial as religion. The success of the A.P.A., for Debs, was nothing more than a reflection of labor’s overall fragility.Footnote 32

The A.P.A. was more than a passing concern for Eugene Debs. A year before publishing his denunciations of the anti-Catholic organization, Debs warned railroad workers in Milwaukee about A.P.A. men in labor organizations. Again, he argued that the A.P.A. threatened to divide the labor movement by sowing distrust based on religious differences. This particular speech angered A. C. Macrorie, the often labor-friendly editor of the Wisconsin Patriot, who held a grudge against Debs for years. Like William Traynor, Macrorie eventually concluded that Debs must be a “Jesuit,” perhaps inadvertently proving Debs’s point.Footnote 33 Debs made similar charges against the A.P.A. in 1895, when he was quoted as saying: “The American Protective Association has torn and lacerated organized labor, set brother against brother, and I am persuaded that the seeds of it were sown by the oppressor’s hand.”Footnote 34 Again, Debs returned to his conclusion that only the railroad companies could have created something as harmful as the A.P.A. It surely would have shocked and frustrated Debs to learn that Henry Bowers and his friends established the A.P.A. to aid labor’s cause, rather than to cut it off at the knees.

Newspapers also complained about A.P.A. efforts to oust Catholics from labor organizations. In 1891, for example, an article in the Nebraska-based Grand Island Independent channeled Debs in accusing the A.P.A. of “playing sad havoc with the Knights of Labor, with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and other kindred organizations and is spreading strife and turmoil where harmony and fraternal feeling previously existed.”Footnote 35 Such a quotation not only helps contextualize Debs’s anger as a member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers but also suggests that other working-class men followed the path of Arnold Walliker and J. S. Hatfield. Dedicated members of the Knights of Labor, for whatever reason, decided that working-class activism could not succeed with Catholics. These workers turned to the A.P.A. but did not abandon their commitment to the labor movement.

Although the power of the Knights of Labor was waning by the early 1890s, the A.P.A.’s blend of anti-monopolism and anti-Catholicism also appealed to some involved in arguably the most famous working-class political movement of the nineteenth century: Populism. One A.P.A. leader saved a newspaper clipping from 1895 in which Tom Watson, Populist radical and vice presidential candidate of the People’s Party, endorsed the A.P.A. and its principles. The newspaper quoted Watson as saying, “As you perhaps know, the Catholics fight me bitterly because I endorsed the principles of the A.P.A. and advocate them in my paper.”Footnote 36 Another prominent Populist reformer, Charles W. Macune, seemed to have drifted toward the anti-Catholic wing of the anti-monopoly movement by the mid-1890s. He started his own nativist periodical, the Republic, in 1896. While the newspaper did not attract many readers, William Traynor notably publicized the new venture in his Patriotic American. Footnote 37 A.P.A. newspapers and internal correspondence even suggested that organizational leaders were working with Macune prior to the 1896 presidential election.Footnote 38 However, connections between Populism and the A.P.A. also extended beyond these movement leaders. One historian described how many North Carolina Populists “worried about the growing Roman Catholic … menace in American society that, when coupled with other forms of economic and political centralization (monopolies and partisan politics), indicated a general drift in the land toward tyranny.”Footnote 39 A little farther south, the A.P.A. State President in Georgia once mentioned in August 1896 that his local council in Augusta had more Populists than Democrats.Footnote 40

As the A.P.A. attracted folks within the Knights of Labor and the Populist movement, some Catholic periodicals highlighted the damage they thought the A.P.A. was doing to the labor movement. An A.P.A. newspaper in San Francisco reprinted an article from one Catholic periodical in California that called the A.P.A. “a menace to labor,” repeating Eugene Debs’s argument that the organization divided the working class. For the labor movement to progress in its efforts against American corporations, the article continued, the A.P.A. needed to be stamped out. Ironically, the A.P.A. Magazine in San Francisco viewed the Catholic plea for working-class solidarity as clear evidence of the righteousness of the A.P.A.’s mission. The A.P.A. Magazine saw this as a ploy – a false assurance that would lull Protestants into complacency and allow the Catholic Church to increase its presence in labor organizations without raising suspicions about its ultimate goal.Footnote 41 In the end, while Traynor once told Eugene Debs that the A.P.A. could have no quarrels with independent Catholics, Catholic laborers seemingly could say little to convince A.P.A. members that the church hierarchy did not control them.

The A.P.A. worried about labor unions, in particular, because they were centralized, influential loci of power that could be infiltrated and then weaponized by the Catholic Church. In 1894, Joseph Bradfield, an A.P.A. member in Washington, D.C., informed readers of the Patriotic American that the Roman hierarchy had placed an American priest named Robert Burtsell in charge of establishing Catholic labor organizations in the United States. This most recent development, however, was an extension of what was already happening, according to the author. Bradfield claimed that “all the leaders of the great labor unions … are under the control of the jesuits [sic] already; in fact, that they are out and out papists.” He offered further evidence, listing the officers of the local Bricklayers’ Union No. 1 in Washington – all of them supposedly Catholic. Bradfield warned Protestant clergy and politicians, “They should study the situation carefully, and warn their flocks, many of whom, no doubt, belong to trades unions, against the danger of being entrapped by the machinations of the jesuits [sic].”Footnote 42 In his 1895 A.P.A. national address, William Traynor explained exactly how this ploy would work:

The tactics pursued by papists in these organizations are not new to old protestant labor leaders: first, they create disaffection among the protestant members, and then by skilful [sic] coalition with the section which will promise them the largest amount of authority, elect members of their own faith to the offices of trust. Where they cannot effect these results they sow dissension and keep up continuous contention until disorganization is effected. Once these organizations are in the hands of the papist leaders, the priest is master of the situation.Footnote 43

This conspiratorial thinking drove the A.P.A.’s long-standing opposition to Terence Powderly, who was Catholic, as the Grand Master of the Knights of Labor. As seen earlier, though, this same anti-Catholic logic existed within the Knights of Labor itself. While it is possible that those anti-Catholic Knights were also A.P.A. members, Powderly dealt with A.P.A.-style attacks from both within the Knights and from outside organizations like the A.P.A.Footnote 44

Despite the perceived danger from the Church hierarchy and Catholic workers, several key A.P.A. leaders thought that labor unions remained an important tool to combat corporate monopolies. But for them to be effective, Catholics needed to be removed and prevented from joining. Arnold Walliker once revealed to a scholar that he and Bowers did not start the A.P.A. to attract defectors from the Knights of Labor. Rather, the anti-Catholic organization began, in part, as a resistance movement within the Knights itself.Footnote 45 That is not to say the A.P.A. existed as a means to purify all labor organizations. Some, William Traynor believed, were lost causes. In his 1895 annual address, the Supreme President proclaimed, “Let it not be deduced from these remarks that I am opposed to labor unions or the sacred rights of labor, but I strongly urge protestants to avoid all labor unions where papists hold the balance or the reins of power.”Footnote 46 Thus, while many A.P.A. leaders were committed to the labor movement, unions required purification and, subsequently, constant vigilance in the face of Catholic subversives.

Affiliations with the Knights of Labor and an animosity for corporations did not mean that all A.P.A. members supported non-corrupted labor unions. In fact, the same anti-monopoly sentiment that drove the order’s critique of railroads and financiers grounded its critique of organized labor: unions were economic and political blocs that could be marshaled to benefit those in power. Henry Bowers once wrote an editorial in 1903 that accused Samuel Gompers of effectively treating the American Federation of Labor (AFL) as a political machine, using the AFL as a vehicle for delivering votes to the Democratic Party. A lifelong Republican, Bowers rhapsodized about the majority of working men, supposedly 88 percent of laborers, who stood politically independent and outside of labor union control. “This 88 per cent, the large intelligent per cent of the labor people, are an independent people,” Bowers wrote. “Educated sufficiently and wise enough to know where to cast its vote without a partisan dictator.” These specific comments about Gompers and the AFL surely were influenced by Bowers’s political loyalties. However, his distrust of organizational partisanship was, by all accounts, genuine. Bowers designed the A.P.A. to be a nonpartisan fraternal organization, endorsing politicians based on policy rather than party, and local councils across the country indeed supported Republicans, Democrats, Populists, and other third-party candidates. In fact, efforts by the third Supreme President, John Echols, to throw the weight of the A.P.A. behind the Republican Party in the Election of 1896 significantly contributed to the organization’s decline into irrelevance. Organizations, whether a labor union or the A.P.A., should never strip a man of his economic or political independence.Footnote 47

While the A.P.A. charged that Catholic immigrants were too subservient and destitute to be either effective union members or proper American producers, the organization believed that those immigrants were products of their environment. The institutional Catholic Church and its clergy purposefully shackled the minds of its flock and kept them poor. James Sargent explained:

In fact, the A.P.A. regards the laity of the Roman Catholic Church as victims of error and superstition—born and bred into a system of religious slavery, from which it is our duty to try and set them free by assisting to break down the power of the pope and his emissaries in this country, and expose and counteract the methods by which these victims are held in bondage and compelled to contribute liberally of their hard-earned wages to the support of an institution that tends rather to degrade than to elevate them, and is designed to keep them under the control of their ecclesiastical masters, rather than to make them self-reliant, independent citizens.Footnote 48

Sargent and the A.P.A. did not argue that something innate in the everyday Catholic was deficient. They had been molded into dependent individuals by an authoritarian, greedy, and retrograde institution that desperately desired the United States for itself. The A.P.A. fought to restrict the flow of Catholic immigrants into the country, but the group ultimately considered obedient Catholic workers to be symptoms of a more noxious disease: the institutional Church. That formulation held true when it came to debates over labor regimes in American industrial capitalism. If lay Catholics were not autonomous workers, the A.P.A. reasoned, it was only because the Catholic Church itself stood against free labor. And, as Sargent did, the organization readily connected the Catholic Church to the most potent anti-free-labor symbol of the nineteenth century: slavery.

Catholic Labor as Slave Labor

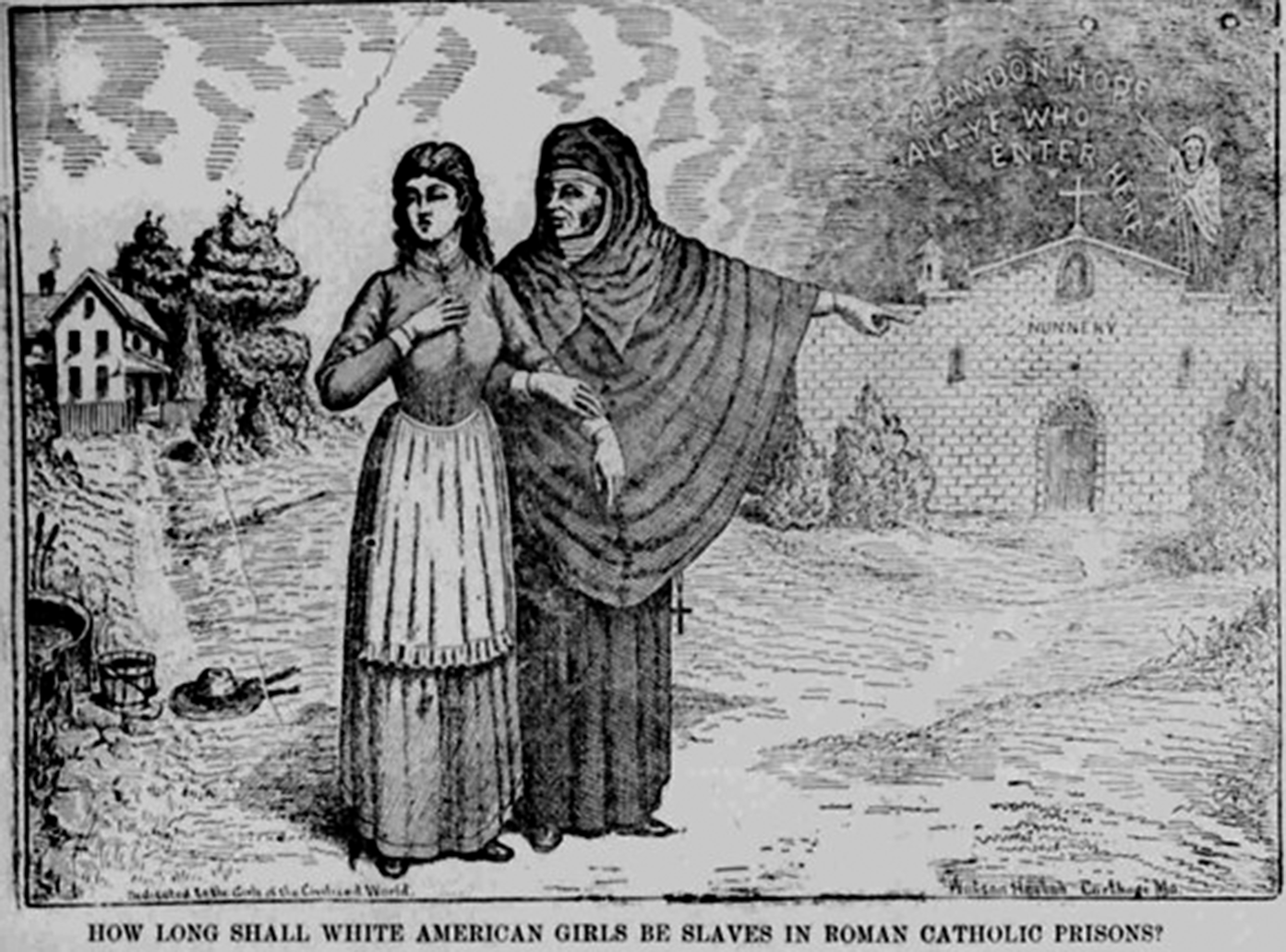

Omaha’s A.P.A. newspaper, the American, published a political cartoon in November 1897 that exclaimed, “HOW LONG SHALL WHITE AMERICAN GIRLS BE SLAVES IN ROMAN CATHOLIC PRISONS?” (Figure 1) Readers would have recognized the dangers that Catholic convents purportedly posed to Protestant women. The “nunnery” – with the black cloud, shrouded skeleton, and threatening message above it – would have evoked fears about sex and gender. Fabricated tales of escaped nuns, such as Rebecca Reed and Maria Monk, were bestselling publications in the nineteenth century and told well-worn stories of sexual and physical abuse within convent walls. Racial and ethnic anxieties were present, too. The artist identified the particular threat to white women, dedicated the cartoon to “Girls of the Civilized World,” and made the nun’s face darker than that of her counterpart.

Figure 1. A cartoon, “Dedicated to the Girls of the Civilized World,” warns readers about the dangers that Catholic convents and charitable institutions posed to young, white women. In the mind of the American Protective Association, the reliance on unpaid, coerced labor to make hefty profits was particularly evil. From the American (Omaha, Nebraska), November 19, 1897.

Emblematic of anti-Catholicism in the Gilded Age, however, even familiar convent tales could not escape political economy. The unprotected young woman was fetching water from a basin in the bottom left of the cartoon, and the nun seemingly targets the young woman, in part, because she can do domestic work.Footnote 49 The importance of domestic work was reinforced in the article below the cartoon. It claimed to offer testimonials from girls and young women inside a convent, the House of the Good Shepherd in St. Paul, Minnesota. The inmates, as they were called, all mentioned toiling in “the laundry.” One girl “described the food as bad, the laundry [as] cold,” while another inmate claimed to be “unaccustomed to washing and did not know how to do such work well.” The latter was “slapped in the face in the iron-room for looking around” for guidance. Ultimately, between two testimonials, the author summed up their understanding of the collective day-to-day experiences inside the House: “hard work, cruelty, and neglect.”Footnote 50

That “hard work” worried the A.P.A. The order claimed that U.S. Catholic institutions coerced women and children into unpaid labor, all under the guise of charity. Nuns and priests made and sold devotional materials, with the revenue enriching the Church. Orphans in New York sorted cards and fulfilled orders for religious items, while young women at reformatory institutions sewed shirts or did laundry for hours each day. The A.P.A. was outraged that these women and children seemed to receive nothing in compensation. In the anti-Catholic press, money-making activities partially defined life at Catholic convents and charities. This coerced labor regime supplied massive profits to what they called the Catholic corporation. As most Gilded Age Americans debated whether economic independence was still possible within industrial capitalism, the A.P.A. claimed that the Catholic Church had established a hidden and profitable form of slavery that violated American ideals of free labor.Footnote 51

Nineteenth-century Americans often compared Catholicism to slavery, and lay Catholics to slaves. During the Civil War, some abolitionists even claimed that slavery and Catholicism were two sides of the same coin. Historians have argued that discourses of Catholic slavery emerged in the nineteenth century amid conflicts about middle-class, Protestant ideas of politics, education, and gender. The A.P.A. both borrowed from and contributed to these discourses. For example, the Supreme State Deputy of the New York A.P.A., James Sargent, published Why I Am an A.P.A. in 1895. The book includes familiar chapters: how the Catholic Church “is the avowed Enemy of the Republic and Its Free Institutions,” how the Catholic Church opposes the public school system, and how the Catholic clergy has been “charged with Immorality, Criminality and Cruelty to Women and Children.” Sargent often relied upon slavery metaphors. He claimed that American Protestants who put Catholics into political office were “none but cowards or natural-born slaves.” While some connections between Catholicism and slavery in Why I Am an A.P.A. may be familiar to historians of American anti-Catholicism, the rhetoric of Catholic slavery in A.P.A. writings also extended to political economy.Footnote 52

Nineteenth-century debates about political economy relied on slavery, both as a real labor regime and as a rhetorical device. It operated as an essential foil for proponents of free labor ideology prior to the Civil War. Northern wage workers and artisans defined their independence and whiteness by the fact that they were not chattel slaves. Historian David R. Roediger has shown that “the bondage of Blacks served as a touchstone by which dependence and degradation were measured.” Following emancipation, though, slavery remained a crucial tool for those involved in the labor movement. Reformers talked about the “wage slave,” the worker whose hunger drove them to take jobs with the meagerest of pay. Wage slavery spoke to working-class fears about permanent wage work and the fantasy that was the freedom of contract.Footnote 53

Wage slavery served as a common economic critique during the second half of the nineteenth century, but racial anxieties did not disappear. White Americans developed a racialized image of Chinese laborers, who were called “coolies.” Coolies referred to Chinese contract laborers whom southern plantation owners purchased to replace Black slaves, or low-wage Chinese workers in the American West. Coolies, according to white working-class leaders, were slaves. They neither demanded high enough wages nor spent enough money as consumers to be independent men. This lack of labor organization, as well as consumerism, made Chinese laborers dangerous. Racialized ideas such as these informed organized labor’s support of Chinese exclusion. Ultimately, as industrialization clashed with ideas of economic independence, white working-class labor reformers used slavery both as a metaphor to identify threats to American capitalism and as a weapon to label those whom they deemed unfit for economic citizenship.Footnote 54

William Traynor wielded the Patriotic American as such a weapon. He reprinted articles from other newspapers and wrote his own columns, accusing the Houses of the Good Shepherd of enslaving women to benefit the Church. Houses of the Good Shepherd were Catholic charitable institutions, run by members of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd throughout the United States. They took in ostensibly delinquent girls and young women, transforming them into productive workers and virtuous women. The A.P.A. raised concerns about all sorts of Catholic monasteries, convents, and charitable institutions, but the Houses of the Good Shepherd seemed to draw special ire from the organization. A.P.A. periodicals across the country called out Houses of the Good Shepherd by name and contended that these “charitable institutions” were a mere public front that hid the real purpose of the institutions: profiting in souls and money. The Patriotic American alone printed stories about the Houses of the Good Shepherd from cities like Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, and New York. Based in San Francisco, the A.P.A. Magazine even printed stories about Houses of the Good Shepherd as far away as Baltimore. These stories all told tales of coercion, wrongful imprisonment, and arduous labor. The articles were akin to the many salacious nineteenth-century stories of escaped nuns, which inspired convent burnings and bestselling books, because they focused on enslaved and exploited women. But the A.P.A.’s convent tales often had an important twist that reflected the Gilded Age world of industrial capitalism. These canards ditched what has been called the “crypto-pornographic anti-Catholic tales of abduction and seduction,” characterized by Rebecca Reed and Maria Monk. Instead, Traynor and other anti-Catholic newspapers claimed that the Houses of the Good Shepherd proved that, if left unchecked, the Catholic Church would deprive working people of their independence. “This is nothing but abject slavery,” the A.P.A. Magazine exclaimed, “and is worse than death itself, and has not the slightest tinge of charity in it. It converts a girl into a machine for the profit of her captors and robs her of her individuality and blights her life forever.”Footnote 55 To the A.P.A., Catholic labor regimes represented the antithesis of an ideal American economy because they purportedly trafficked in slavery.Footnote 56

Sisters of the Good Shepherd, indeed, focused their ministry on women who had been ostracized from society. They dedicated their lives to reforming women who had been accused of theft or who had deviated from late nineteenth-century sexual norms, which often meant prostitution or simply having sexual experience prior to marriage. They sought to convert these women, often poor Catholic immigrants, from delinquents into productive citizens. One sympathetic study, published by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in 1910, said it was “[p]itiful … to look into those beautiful young eyes and know they have looked on vice almost from the cradle.” These women religious (as they were called) ultimately sought to “awaken the souls and the minds of these poor little ones, besides training them to bodily cleanliness and habits of industry and order.” In this way, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd fit within broader late nineteenth-century reform narratives, in which middle-class men and women strove to clean up cities, stamp out vice, and police female sexuality. However, Catholic charitable institutions differed from their Protestant counterparts because poor or working-class women often ran them.Footnote 57 That working-class background shaped the Houses of the Good Shepherd and convinced the women religious that poverty was something more than a moral failure.

While the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, like other women religious in the United States, managed their finances with great skill, salvation for themselves and the women in their charge was top priority.Footnote 58 They believed that redemption for these “fallen” women could only come through the Catholic Church, which necessitated regular prayer, but they also stressed that redemption for poor immigrant women required more. Sisters of the Good Shepherd considered economic structures. The realities of poverty meant that sexual, religious, and civic purity could only be achieved if these women found jobs. Irish Catholic women often supported family back in Ireland or the States, and prostitution became a legitimate means of fulfilling that familial obligation. The women religious believed that wayward women, without job skills or steady income, would almost certainly backslide into prostitution. They had no other choice. To combat this end, the sisters trained immigrant women in domestic services and the sewing jobs that Irish Catholic women commonly held in late nineteenth-century cities. The sisters, according to a self-published memoir of the order, strove to “preserve the innocence of girls” and lead them to “paths of industry and self support.” The result was a highly regulated regimen of prayer and labor, overseen by women religious, separate from the outside world. The Sisters of the Good Shepherd ultimately maintained that their girls and women could be redeemed through both spiritual and material work.Footnote 59

The first Sisters of the Good Shepherd traveled to the United States in 1842, settling in Kentucky. By the end of the nineteenth century, women religious operated Houses of the Good Shepherd – also called Magdalene Asylums or Magdalene Laundries – from Massachusetts to Louisiana to Washington State. The Houses always accepted women and girls who came voluntarily, or at the behest of family members, and those women had the freedom to leave whenever they chose. Financial support for those voluntary admits was uneven. Bishop James Duggan encouraged the sisters to come to Chicago in 1859 and contributed money to their efforts, while the House of the Good Shepherd in New York originally relied on private donations because Archbishop John Hughes opposed both the House and what it implied about the women of his diocese.Footnote 60

Always, though, the sisters relied upon money from the sewing and laundry done by the women and girls under their supervision. Houses, like the ones in Chicago and New York City, eventually received public money because they began taking in women who chose to serve their sentence at a House of the Good Shepherd rather than at an almshouse. This characteristic often gave the House a quasi-state or quasi-correctional atmosphere, in which inmates could not leave of their own volition. However, Houses never stopped accepting voluntary arrivals. One House of the Good Shepherd in Hartford, Connecticut, had fifty-two inmates in 1905: seventeen women for whom the city paid, nine women for whom relatives paid, and twenty-six women for whom the House itself paid. The few studies that exist of individual Houses in the United States indicate that money to operate the institutions was always scarce. The Sisters of the Good Shepherd thus viewed the labor performed by their girls and young women simultaneously to be job training, redemptive, and a means of necessary funding. Those admitted to the Houses did not receive wages, but their labor paid for regular meals and a roof over their heads.Footnote 61

Women working in Houses of the Good Shepherd often had a dimmer view of their supposed path to redemption. They had little to no access to the world outside the asylum walls, and the sisters frequently gave them names other than their own. They lost control of their day-to-day lives and their sexual independence. Inmates occasionally tried to escape or successfully ran away, such as one girl who was caught spooning with a man on a park bench while still wearing her blue-gray penal dress. Newspapers eagerly reported on and sensationalized these stories. Jennifer Cote has shown that Hartford’s Daily Courant used women’s connection to the local House of the Good Shepherd as a license to accentuate the perceived deviance of escaped inmates and to further sexualize them, and the nativist press used the same titillating tactic. Furthermore, some girls and young women tried to reclaim their independence as wage earners after they left the Houses. The sewing and domestic service work was physically taxing and went unpaid. In articles about released women or those inmates who ran away, lawyers routinely foregrounded their clients’ unpaid labor. Although it is unclear to what extent Good Shepherd stories in the Gilded Age nativist press were based on real women or real legal cases, legal efforts to compensate women for past coerced and unpaid labor in worldwide Magdalene Laundries have extended into the twenty-first century. In the end, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd wanted to give poor immigrant women a better life through discipline, prayer, and job training. But some of the same poor immigrant women challenged those reform efforts. These dissident and litigious women fought for a different kind of redemption, a kind in which they could assert their sexual and economic independence.Footnote 62

The Patriotic American regularly republished tales about the Houses of the Good Shepherd. One such article appeared on its front page in March 1891. It recounted the plight of a young woman named Nora Shaunessy. A city judge in Chicago sentenced Nora, who was thirteen years old at the time, to six weeks at the House of the Good Shepherd for stealing coal at the railroad tracks. Nora reportedly was held captive for over five years, released only because her parents hired a lawyer to aid in rescuing their daughter. The article included a statement from Nora herself, a day after she gained her freedom. She explained that the Sisters of the Good Shepherd called her Tony. “My real name,” Nora said, “was known to no inmate of the institution except the sisters. Nor did I know any other girl by her right name.” The effect was to make it feel as if the Sisters of the Good Shepherd removed all connections that inmates had to the outside world, erasing their individuality and personhood.Footnote 63

Nora Shaunessy’s narrative mirrored other House tales that were featured in the Patriotic American. Regardless of its veracity, her story offers a useful window into the main concerns that A.P.A. leaders had about the Houses of the Good Shepherd and Catholicism.Footnote 64 Whereas convent tales earlier in the nineteenth century would largely focus on sexual immoralities over the harsh working conditions in Catholic institutions, Gilded Age House tales in A.P.A. newspapers increasingly foregrounded labor abuses. And, indeed, Nora’s story centered on her coerced, unpaid labor. The girls and young women received religious education and prayed, but mostly, Nora claimed, “All I did was to work, work, all the time.” Her labor, in fact, explained why the sisters refused to let Nora leave. The House wanted to retain “the valuable services of the girl, who appears to have earned money for the sisterhood.” While proselytization and recruitment to the sisterhood played a part, the article argued that the Church had little interest in reforming girls. They desired unpaid labor and were willing to falsely imprison girls like Nora to secure it.Footnote 65

William Traynor knew precisely what to call someone who was held captive and forced to work without monetary remuneration. He wrote that Nora “was brutally treated and made a slave.” And Nora was not the only one. Traynor charged that the Houses of the Good Shepherd imprisoned countless Noras, compelling them to work. He described the operation of Detroit’s House: “One manufacturer in the city has placed there some fifty sewing machines on which the slaves are kept at work making overalls.” Such rhetoric was not limited to Traynor. The language of slavery accompanied many stories about the Houses of the Good Shepherd in articles that the Patriotic Republic republished. For instance, when a woman brought a lawsuit against a House in Troy, New York, claiming false imprisonment, her lawyer exclaimed: “They gave Annie Amoe a pair of slippers, underclothes, a dress and hat. What did they get from her[?]. Twelve hours of hard labor and her board paid by the county, gave them the servitude of a slave. What did she get in return? Barred doors, not even the right to look out of a window on God’s bright day.” Amoe’s lawyer demanded damages from the House in Troy to “teach the defendants that this is a free country, and no one can, without process of law, be deprived of personal liberty.” Even if Amoe and her lawsuit were fabricated, the article’s author expected its readers to understand that personal liberty for Amoe demanded that she be paid for the industrial work she had done for years.Footnote 66

The A.P.A. did not believe that the coercive labor regimes in Catholic charitable institutions were limited to the United States. The Catholic Church was a global organization, and its business strategy was too. Reprinted from the New York Sun, Traynor published an article on the front page of the Patriotic American in January 1892 that focused on the exploitation of Catholic converts in China. The article claimed that newly constructed convents in China were nothing more than silk factories. The author, who identified themselves as J. J. V. M., wrote, “The ‘nuns’ are young native women compelled to weave by mercenary missionaries, who realize richly from their traffic.” This modern-day slavery did not go unnoticed by locals. “The massacres of Christians [sic] and the burning of convents” in China was “often nothing else than the delivering of natives by their relatives from confinement in these ‘convent’ factories.”Footnote 67 In England, a woman named Miss Golding, who claimed to have escaped from a convent, did not spin a yarn of lascivious priests or sexual improprieties. Instead, she emphasized that the Convent of La Sainte-Union des Sacrés-Coeurs only thought of her as a profit source. The convent lusted after her personal wealth, and she did nothing but “work, work, work all day, in a way which people in the outer world cannot have conception of.” Teaching English, music, singing, and drawing every day for twenty-five years, Miss Golding estimated that she made £1,000 for the convent annually – money she never saw herself.Footnote 68 In the anti-Catholic press during the Gilded Age, stories of escaped nuns and convent atrocities across the globe focused increasingly on financial, not sexual, exploitation.

Catholic newspapers responded defensively to condemnations of the Houses of the Good Shepherd in the 1890s. Articles provided readers a history of the order, focusing on the sacrifices and labors performed by the women religious. The Catholic Telegraph in Cincinnati, Ohio, called the sisters “a triumph of the mercy of the Heart of Christ,” while the Monitor in San Francisco endorsed an opinion that “patient fortitude should earn for the good Sisters the title of heroines in the eyes of the world.” While these articles did not mention the anti-Catholic order by name, A.P.A.-style attacks were top of mind for these Catholic publishers. The Monitor acknowledged the stakes of the debate when it republished an article written in response to “a party of curious, prying women who demanded admission on the grounds of being a benevolent society out on an ‘investigating’ tour.” The papers knew that non-Catholic Americans distrusted what occurred behind the Houses’ closed doors. Whether it was the Charlestown convent burning in 1834, a group of reform-minded women in 1893, or the A.P.A. itself, Catholic women religious and the Catholic press defended their institutions from public “investigations.”Footnote 69

These Gilded Age articles from Catholic newspapers in Cincinnati and San Francisco refuted nativist charges of false imprisonment and coerced labor. The Catholic press, whether implicitly or explicitly, understood that the A.P.A. and its ilk had linked Catholic charities and slavery. “As no compulsion is used in their entering the House of the Good Shepherd,” the Catholic Telegraph explained, “so no restraint is needed to keep the women there.” The articles reinforced this freedom of movement by emphasizing the number of magdalens at each House. Magdalens were laywomen who could not enter the Order of the Good Shepherd, because it was “impossible for any person whose reputation has been in the slightest degree tarnished to be a member,” yet still wanted to devote themselves to the House and its work. How could the A.P.A. claim that Houses of the Good Shepherd were institutions of slavery, the Catholic press seemed to ask, if dozens of women voluntarily committed themselves to their respective House for life?

These papers also emphasized that the labor the girls and women undertook at the Houses was not exploitative. It was job training. One article wrote, “The women and girls are taught various trades and handicrafts in the industrial school, and are thus fitted to earn a livelihood.” The domestic labor that Nora and Annie Amoe reportedly did was a pathway to a better life. Plus, the Catholic Telegraph hinted that, even if the work was unpaid, the Houses did not make much money anyway. “Store shirts and laundry work are the most important branches of industry,” they wrote, “but the prices have gradually undergone such reductions that at present a mere pittance is paid for really good work.” The Catholic press argued that the young women and girls could leave when they wanted, often devoted their lives to the cause, learned occupational skills that would prevent them from returning to prostitution, and did quality handiwork, but they did not enrich anyone. The Houses of the Good Shepherd, the Catholic press concluded, did not partake in slavery.Footnote 70

Despite those assurances, the concerns about labor practices inside Catholic charities partly motivated one of the A.P.A.’s core policy demands: public inspection of Catholic institutions. James Sargent’s Why I Am an A.P.A. lists nine political principles of the organization. Number seven advocated for “private schools, convents, nunneries, monasteries, seminaries, hospitals, asylums and other educational or charitable institutions to be open to public inspection and under governmental control.”Footnote 71 An A.P.A. publication from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, reiterated the same demand, specifically calling out the House of the Good Shepherd.Footnote 72 A campaign to “open the nunneries” helped the A.P.A. expand in places like Oregon, while state politicians elsewhere either pushed public-inspection legislation or tried to prevent women from being sent by government officials to Houses of the Good Shepherd in Michigan, Minnesota, and Washington. To highlight the A.P.A.’s concern about money-making activities in Houses of the Good Shepherd, Washington State passed an A.P.A.-supported bill in 1895 that only granted tax-exempt status to church properties if they opened their financial books and showed that income was used solely for charitable purposes.Footnote 73

While the anti-Catholic order desired governmental oversight of Catholic institutions, they were also willing to take matters into their own hands. The Women’s American Protective Association (W.A.P.A., an auxiliary group) in Kansas City ran “Door of Hope,” a twelve-room house that offered an alternative to the House of the Good Shepherd. Door of Hope claimed to house twenty-one girls in 1895 and was “crowded for room,” with more girls wanting to come. John B. Stone – a local county judge who was a member of the A.P.A. and whose wife was a leader of the city’s W.A.P.A. – even donated an acre of land to the council in hopes of erecting a larger, permanent institution.Footnote 74 The W.A.P.A. in Kansas City, however, did not limit its attacks on the local House of the Good Shepherd to mere institutional competition. They once showed up at the local House of the Good Shepherd in 1894, demanding entrance to release a woman named Annie Devers. The women religious denied the W.A.P.A. members’ request. In response, the W.A.P.A. turned to the courts and successfully secured Devers’ release. When reporting on the story, the American talked to another former inmate of the House of the Good Shepherd in Kansas City. Tellingly, after the reporter asked the young girl about the food and drink provided for her, the reporter asked, “What kind of work did you do?”Footnote 75

The A.P.A. also worried about clerical sexual misconduct in Catholic institutions and confessionals. In fact, like many nativist writers throughout the nineteenth century, James Sargent devoted an entire chapter to the subject in his book. However, by reducing calls for public inspection of Catholic institutions to nothing but longstanding Protestant anxieties about gender and sexuality, it obfuscates the obsession that A.P.A. newspapers had with labor practices in the Houses of the Good Shepherd. Paying more attention to the relationship between anti-Catholicism and political economy, particularly to Gilded Age debates about free labor and economic independence, explains why the A.P.A. called for public inspection of Catholic institutions and their financial records, the anti-monopoly origins of the A.P.A., and the order’s destructive desire to purify labor organizations. The A.P.A. did not flourish in the final decades of the nineteenth century because it seized on economic conflicts and “converted them into religious and nationalistic ones,” as has been suggested.Footnote 76 Upon joining the organization, a few of the A.P.A.’s members deserted their various commitments to labor organizations. These anti-Catholic reformers did not believe that lay Catholic dependency and unchecked clerical power wholly explained the negative effects of industrial capitalism; instead, they argued that Catholicism exacerbated the existing structural problems of the U.S. economy. The A.P.A.’s anti-Catholic politics, in other words, were neither separate nor a distraction from working-class efforts to reform American capitalism. However, the A.P.A. ultimately hindered the political success of working-class movements by sowing distrust within labor groups and opposing interdenominational political coalitions, just as Eugene Debs warned it would.

Understanding the A.P.A.’s blend of anti-Catholicism and anti-monopolism is necessary because it can help historians better recognize how the A.P.A. influenced ideas and movements into the twentieth century. For example, in January 1912, the front page of the famous nativist periodical the Menace warned of “An Astounding Conspiracy of Evil to Turn the Labor Organizations Into Roman Catholic Hands.”Footnote 77 This claim would have looked familiar to any former A.P.A. member. Such connections to the A.P.A. suggest that the Menace did not articulate a new form of anti-Catholicism that was unique to the Progressive Era, as has been suggested.Footnote 78 Instead, the newspaper had a ready-made constituency, carrying many of the A.P.A.’s anti-monopoly critiques of the Catholic Church into the early twentieth century. Some progressive politicians even worried that the A.P.A. and its lingering relevance would harm them at the ballot box. Theodore Roosevelt complained to his son, Kermit, in October 1908 that A.P.A. sentiment remained strong. He wrote, “But in the West it is very strong. It may cut down our vote everywhere and may even lose us Ohio and Indiana. It is an infamous movement.”Footnote 79 Indiana would eventually become a stronghold of the Second Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, and while historian Linda Gordon recently recognized that the A.P.A. influenced the Second Klan, the A.P.A. likely shaped Klan ideology, strategy, and membership more than historians have realized.Footnote 80 For example, one older study of the Second Klan in Denver, Colorado, offhandedly noted that several local Klan leaders were children of former prominent A.P.A. leaders.Footnote 81 More research on the potential connections between the A.P.A. and Progressive Era nativism is necessary. This kind of research would help us better assess not only the broader historical legacy of the A.P.A. but also the full impact of anti-Catholicism in working-class thought during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.