Introduction

Elections are normally considered as accountability mechanisms that allow voters to vote out those incumbents that do not deliver on their promises. Yet, recent electoral contests in Western Europe, North America and Latin America demonstrate the limits of traditional models of retrospective economic voting on the basis of observed macroeconomic indicators (sociotropic voting) or personal economic circumstances (pocketbook voting) (Anderson, Reference Anderson2007). Candidates or parties with a strong record of economic stewardship have been booted out of office (e.g., the U.S. Democrats in 2016), while governments engaging in perilous policy experimentation and brinkmanship politics have been voted back into office by their national electorates (e.g., SYRIZA in Greece or the Tories in the United Kingdom). Salvini's run‐ins with the European Commission on Italy's draft budget proposals, Trump's unsuccessful efforts at pushing immigration restrictions through Congress or even recent policy failures with respect to the handling of the COVID‐19 pandemic and the vaccine roll‐out, showcase the limits of executive power; yet, at times, leaders' inability to implement their policy agenda in the face of domestic or supranational constraints appears to enhance their popularity.

In this paper, we focus on the role of external supranational constraints and use the above empirical puzzle in order to propose a theoretical argument on how voters shift from outcome‐ to input‐oriented voting in the presence of such constraints. In contexts where countries are heavily dependent on globalization‐related systemic factors, voters often place a higher premium on the incumbent's actions as opposed to their results, as the former become acutely aware of these constraints on the government's ability to deliver. These actions provide information about the true traits of the incumbent and what they would do if the supranational constraints were to be loosened. This line of reasoning leads us to a key prediction: Voters may in fact reward incumbents at the ballot when the former perceive the latter to have tried but eventually failed to overturn an unpopular policy mix, thereby showing that they can be trusted. To refine our argument further, we show that voters who exhibit higher levels of perceived victimhood care more about electing a representative and congruent government prone to giving voice to their desires and beliefs.

We test the micro‐foundations of this argument against a survey experiment conducted within a political environment heavily subject to supranational constraints, namely the September 2015 Greek parliamentary election. Few elections have challenged the conventional wisdom of retrospective outcome‐oriented voting more than that. Following a failed and very costly renegotiation of the country's bailout agreement with its creditors and on the back of a strong anti‐austerity mandate delivered by 61 per cent of the Greek electorate that voted to reject the latest proposal by the creditor institutions in the July 2015 referendum, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras announced a snap election in September 2015, which his radical left‐wing party of SYRIZA won quite handily – notwithstanding its unfulfilled promises and the deepening of austerity measures – seeing only infinitesimal losses in its vote share.

In light of these circumstances, our treatment arms differ with respect to the priming of the input (i.e., the incumbent's effort to overturn the prevailing austerity framework) and/or the outcome (i.e., the incumbent's failure to relax the bailout agreement's austerity conditions). In line with our argument, we find that the treatment cue emphasizing the effort exhibited by the SYRIZA‐led coalition government increased support for the incumbent party only in combination with the failed‐outcome prompt. Voters, in this context, did not seem to place as much emphasis on the incumbent's ability to deliver in deciding on whether to re‐elect them or not. Instead, they interpreted any information about the incumbent's failed attempts as a signal of the latter's true intentions, trustworthiness, responsiveness and hence of what they would do in the context of an unconstrained domestic policy environment.

The paper proceeds as follows: The following section presents the research question and its relation to the current literature on voting and globalization. We develop our theoretical argument in more detail in the subsequent section and then proceed to present the scope conditions, the research design and the results of our survey experiment. Finally, we conclude by discussing some of the implications of our findings.

Voting and globalization

Extensive research has shown that policy outcomes materializing during a government's term in office are a key predictor of individual vote choices and overall government popularity. To boot, retrospective economic voting has been traditionally seen as one of the main pillars of democratic accountability (Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981). According to this model, elections conform to a reward‐punishment logic: Voters interpret outcomes as signals of the government's competence and performance in office; accordingly, they re‐elect those incumbents who appear to deliver good results and achieve certain targets and vote out those who do not. This accountability mechanism incentivizes politicians to accumulate expertise and exert effort in order to perform well in office, thereby reaping short‐ and long‐term electoral benefits (Bechtel & Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011).

This model relies on the assumption that there is clarity of responsibility (Ferejohn, Reference Ferejohn1986; Key, Reference Key1966). Retrospective performance‐based voting implies that voters can attribute clear responsibility for outcomes to the incumbent. When they are not able to do so, however, due to say institutional and political factors such as the type of government, the number of veto players, the relationship between the executive and legislative branches or the level of government cohesion, it becomes harder for citizens to form assessments based on outcomes and thus the scope for performance‐based voting diminishes (Dassonneville & Lewis‐Beck, Reference Dassonneville and Lewis‐Beck2017; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013; León & Orriols, Reference León and Orriols2019; Powell & Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993).

Among such factors, a more recent strand of this literature has considered the effects of openness and globalization on democratic accountability (Ezrow & Hellwig, Reference Ezrow and Hellwig2014; Kayser, Reference Kayser2007). The argument in sum is that economic globalization, that is, the process of market integration across space, increases national economies' exposure to external factors over which domestic governments have no control (Mosley, Reference Mosley2005). In addition, the process of supranational political integration, which amounts to a deepening commitment by national governments to a common body of rules and regulations, limits what they can promise and deliver, or else curtails their ‘room to manoeuvre’ (Hellwig, Reference Hellwig2016; Kosmidis, Reference Kosmidis2018). Consequently, citizens become less likely to rely on observable outcomes in assessing government performance and deciding how to vote. In other words, when countries are subject to supranational policy constraints, policy outcomes become less relevant in explaining voters' behaviour, especially in areas where governments have limited room to manoeuvre (Sattler et al., Reference Sattler, Freeman and Brandt2008).

This argument was initially advanced in the seminal work by Hellwig (Reference Hellwig2001), who shows that individual economic assessments in open economies are weakly correlated with the vote for the incumbent. Moreover, this argument is not restricted to voters' subjective perceptions: For example, Hellwig and Samuels (Reference Hellwig and Samuels2007) demonstrate how exposure to the global economy weakens the relationship between country‐specific economic outcomes and incumbent re‐election at the aggregate level. Several scholars have tried to unpack the underlying mechanisms: Alcañiz and Hellwig (Reference Alcañiz and Hellwig2011), for instance, find that in Latin America citizens often blame international non‐elected actors for poor observed economic outcomes, and this induces them to exonerate the incumbent. Others have mostly focused on the role of partisanship as a mediator of the effects of outcomes and perceptions of blame. Fernández‐Albertos et al. (Reference Fernández‐Albertos, Kuo and Balcells2013) find that bad outcomes are discounted by supporters of the incumbent party when particular international actors can be targeted and held responsible.

As much as it has enhanced our understanding of the way international constraints affect voters' decision‐making, this literature still leaves open one important question that remains relatively unexplored both from a theoretical and an empirical standpoint: If such outcome‐based accountability mechanisms that rely on clarity of responsibility and retrospective voting are no longer as relevant, then which voting mechanisms do voters actually use? If the retrospective assessment of outcomes no longer provides a good enough indication of how well the incumbent has performed in office, how do citizens decide whether to re‐elect them or not? At the end of the day, voters are still confronted with a decision at the ballot box. Therefore, despite the voluminous literature on the moderating effects of globalization on the nature of economic voting, still little is known about what replaces the standard retrospective logic in voters' minds.

Most attempts to address this question are based on the idea that voters apply different weights to different policy areas according to the nature of information available in each policy domain. According to Duch and Stevenson (Reference Duch and Stevenson2008), one answer could be that voters focus on those policy areas where signals are less noisy and contain more information about the incumbent's competence. Hellwig (Reference Hellwig2016) also provides evidence that voters shift their attention away from general economic outcomes and onto those policy areas that are less affected by globalization, for example, health care. Another possibility is that voting shifts from a retrospective to a prospective logic. Fernández‐Albertos (Reference Fernández‐Albertos2006) shows that the internationalization of the economy moderates the effect of prospective economic expectations on voting; otherwise put, while the openness of the economy waters down the impact of the retrospective assessment of outcomes on the vote, prospective judgments and expectations can still play a role in shaping voters' behaviour. Finally, Ward et al. (Reference Ward, Kim, Graham and Tavits2015) argue that as deeper economic and political integration constrains parties' ability to credibly differentiate themselves on economic issues, parties choose to politicize other non‐economic issues in the process of electoral competition.

We argue that constructive explanations in this literature on how people vote in the first place – not just what they do not base their vote on – are less convincing in the context of a recessionary crisis environment, where the economy remains first and foremost in the political agenda insofar as unstable macroeconomic conditions threaten people's livelihoods, while at the same time the government is constrained in what it can do. Instead, we put forward an alternative – though not necessarily contradictory – argument, namely that within a globalized and highly constrained policy environment voters will tend to discount policy outcomes as signals of government competence and focus more on policy inputs as signals of government responsiveness and congruence.

Input‐oriented voting under supranational constraints

Canonical models of retrospective voting that regard policy outcomes as the basis of democratic accountability are predicated on the implicit assumption that those outcomes are a direct function of policy inputs. However, globalization may make outcomes more detached from either what governments promise to do (inputs) or the policies that they actually enact (outputs). This tension is particularly pronounced when countries join supranational organizations that formally delimit their governments' room to manoeuvre. Widening the gap between capital markets and democratic politics, globalization creates growing disparities between the sources of ‘input’ and ‘output legitimacy’ (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999) and brings about increasing incompatibility between the functions of ‘responsible’ government (‘for the people') and ‘representative’ government (‘by the people') at the national level (Mair, Reference Mair2009). This trade‐off between responsibility, that is, conforming to the dictates of economic orthodoxy, and responsiveness, that is, pursuing policies that people actually desire, became even starker as a result of the Global Financial Crisis, the Eurozone Debt Crisis as well as the more recent COVID‐19 pandemic (Konstantinidis et al., Reference Konstantinidis, Matakos and Mutlu‐Eren2019). While some have argued that voters will then either focus on post‐material socio‐cultural issues and other policy areas that are not affected by extraneous constraints (Hellwig, Reference Hellwig2016) or follow partisan cues in terms of framing reality (Fernández‐Albertos et al., Reference Fernández‐Albertos, Kuo and Balcells2013), we propose input‐oriented voting as a mechanism by which voters assess incumbents.

In order to develop our theoretical argument, we rely on a distinction between policy inputs, outputs, and outcomes as the essential ingredients of the policy‐formation process (see Figure 1). Policy inputs refer to actions, efforts, ideologies, policy platforms, political rhetoric or else anything that politicians say or do at the pre‐ or post‐electoral stage in order to get elected and influence policy design. Policy outputs, in turn, refer to legislative or executive acts, while policy outcomes amount to either macroeconomic aggregates, such as unemployment levels, GDP growth, etc., or personal economic circumstances. The policy design stage converts inputs into outputs, and the policy implementation stage maps outputs onto outcomes. We assume that voters have different sets of preferences over policy inputs and outputs, common (sociotropic) or personalized (pocketbook) experiences over outcomes, and distinct (prior) beliefs over the links between them, that is, the constraints affecting the policy design and policy implementation stages. As a result, we think of voting mechanisms as the interaction between policy preferences and beliefs over how constrained the policy‐formation process is.

Figure 1. The policy‐formation process.

In the absence of economic interdependence, a closed‐economy policy‐formation process should be less affected by external factors so that outputs clearly reflect inputs and outcomes depend more directly on the incumbent's competence in terms of implementing outputs. Therefore – in line with canonical models of retrospective voting – voters should be expected to vote solely on the basis of outcomes since they do not figure to possess the technical expertise to assess what the optimal mix of policies is, choosing instead to interpret outcomes as direct signals of the incumbent's level of congruence and competence (Becher & Donnelly, Reference Becher and Donnelly2013). After all, one would expect that outcomes – especially in terms of personal economic circumstances – are much more easily observable and less costly indicators than either inputs or outputs, as knowledge of the latter two would entail some level of political sophistication and overall interest in politics.

On the other hand, the presence of supranational policy constraints delimits the process of policy design – as per the ‘room‐to‐manoeuvre’ thesis (Hellwig, Reference Hellwig2016; Kosmidis, Reference Kosmidis2018) – and the emergence of globalization‐induced economic volatility renders the outcomes of policy implementation effectively stochastic – as per the ‘clarity‐of‐responsibility’ thesis (Duch & Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Jensen & Rosas, Reference Jensen and Rosas2020). In other words, the process of political integration compresses the mapping of inputs onto outputs, thereby undermining perceptions of ‘procedural legitimacy’, while the vagaries of economic globalization dilute direct responsibility for policy outcomes, thereby eroding the bases of ‘substantive legitimacy’ (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019). Divergent perceptions about the constrained relationship between policy inputs, outputs and outcomes will give shape to different voting mechanisms depending on the weight placed on each component.

When supranational constraints and external factors are perceived to sever the link between policy inputs and outcomes, voter assessments should be expected to weight the former higher than the latter. To boot, unlike outcome‐based and results‐driven voting mechanisms, input‐oriented voting places more emphasis on government responsiveness, democratic representation and policy congruence with voter preferences (Sattler et al., Reference Sattler, Freeman and Brandt2008). According to this logic, voters assess incumbents on the basis of what the latter try to do while in office and whom they appear to represent, rather than what they have already delivered. Therefore, input‐oriented voting not only rewards incumbent effort and (potentially risky) policy experimentation more than outcome‐oriented voting but does even more so when policy outcomes are incongruous with government actions. In effect, knowledge about outcomes can help voters qualify their priors over the nature of the policy environment and the links between the different stages of the policy‐formation process. Input‐oriented voting is thus predicated on the belief that both domestic policy outputs and outcomes are effectively circumscribed by systemic factors beyond the government's control. In other words, both the policy design and policy implementation stages are perceived as inherently constrained.

The combined observation of effort coupled with bad policy outcomes may thus lead voters to infer that achievable policy outcomes are stochastically related to policy outputs (diffuse clarity of responsibility) – which, in turn, are delimited by the country's international commitments – thereby inducing them to exonerate the incumbent from blame. In effect, failed efforts will more clearly illuminate the difficulty of the task at hand, the inexorable nature of supranational constraints, as well as the contrast between the types of policies that incumbents would implement in the absence of such constraints and those they are actually forced to implement. Therefore, input‐oriented voting can entail both a retrospective assessment of incumbent actions and a prospective assessment of politician types in terms of what they might do in the future in the event that those policy constraints were to be loosened.

In the survey experiment to be discussed below, we actually find that the combined treatment cue of effort and failed outcome reinforces respondents’ belief in a heavily constrained domestic policy environment and thereby triggers mostly input‐oriented voting mechanisms. In such a setting where there is no direct correspondence between government actions and policy outcomes, clarity of responsibility is undermined and input‐based sources of accountability take precedence over outcome‐based ones. Since no politician of any ideological hue or competence level figures to directly affect policy outcomes within a systemically constrained policy environment, voters will tend to favor keeping a responsive (congruent) incumbent in office as only that type may have any chance of making a difference for the better once presented with a certain ‘window of opportunity’ in the future. Otherwise, if voters hold the belief that the incumbent has sufficient control over the policy‐formation process, then they are bound to vote on the basis of the incumbent's record in office, that is, their achieved policy outcomes.

If elections are not just about holding incumbents accountable for their performance in office (moral hazard problem) but also about selecting the right types (adverse selection problem), policy inputs can effectively become more useful screening tools than outcomes. In the presence of binding supranational policy constraints, outcomes (performance) will be less informative about the incumbent's level of responsiveness and congruence compared to inputs (actions). In the context of supranational political integration, a process that delinks outcomes from inputs, voters will choose to elect a representative government that can be entrusted to represent their interests and give voice to their inherent desires and beliefs, rather than what may be perceived as a competent but otherwise unresponsive set of technocrats. As a result, this heightened demand for democratic representation and congruence will place more weight on perceptions of input (or procedural) legitimacy.

In light of our definition of voting mechanisms as an interaction between policy preferences and beliefs over the nature of the policy environment, input‐oriented voting behaviour should not apply to all voters alike. Those voters who believe supranational constraints to be inexorably binding will be more prone to use input‐oriented voting strategies. Conversely, those who do not consider that supranational constraints are strong enough to decouple government actions from policy outcomes will be more likely to use outcome‐oriented voting mechanisms (that are also arguably less costly).

By extension, we argue that voters with extreme anti‐globalization preferences (either ascribing to the equity‐based populism of the left or the identity‐based nativism of the right) will also tend to exhibit a strong sense of victimhood and fatalism by attributing their current circumstances to the inscrutable forces of economic globalization and political integration. In that regard, those more susceptible to a polarizing anti‐globalization rhetoric that paints them as the hapless victims of an all‐powerful global capitalist system, controlled by foreign and domestic elites, are more likely to vote for politicians based on their actions and efforts at challenging those constraints even if those politicians are perceived as having very little discretion over the choice of policy outputs or outcomes. On the other hand, those who are more receptive to the prescriptions of economic globalization and political integration will tend to hold governments accountable for policy outcomes. Our empirical findings are in line with the above theoretical arguments.

In sum, the prevalence of input‐ over outcome‐oriented voting will be effectively determined by how constrained the domestic policy environment is perceived to be. All in all, input‐oriented voting is characterized by three main components: (a) an emphasis on government inputs (effort), (b) an attribution of responsibility for outcomes to external actors that impose supranational constraints and (c) the use of information about inputs and outcomes as a way of updating beliefs over the incumbent's attributes. The combination of these three components can enhance incumbent support despite failure to achieve positive outcomes.

A survey experiment of input‐oriented voting

We designed and administered a survey experiment in Greece right before the September 2015 election in order to prime all three of the above components of our argument and test for the existence of input‐oriented voting. This specific case provides an ideal quasi‐experimental setting for testing the impact of policy constraints on voters’ attitudes and assessments. There is arguably no other advanced liberal democracy that has exhibited stronger signs of political turbulence and economic collapse than Greece under the yoke of three successive bailout programmes and heavily constraining conditionality arrangements. The Greek sovereign debt crisis culminated in a dramatic concatenation of events that brought the economy to its knees and the country on the verge of exit from the Eurozone (aka ‘Grexit') in 2015.

The saga of the Greek bailout negotiations started with the January 2015 election that took place 6 years after the start of the Greek crisis and led to the formation of a government under the radical left‐wing party of SYRIZA and its leader Alexis Tsipras. With a popular mandate to reverse austerity, relieve the debt burden and provide humanitarian aid all within the strict confines of the Eurozone, SYRIZA's atypical coalition government with the nationalist right‐wing party ANEL dedicated its first months in office to the renegotiation of the fiscal targets and structural conditions of the country's bailout agreement with its creditors. As the renegotiation process dragged on – thus igniting fears of an impending deadlock – the primary surplus evaporated, and the overall state of the economy deteriorated. Having failed to reach an agreement, Tsipras called a referendum on 5 July 2015 on the latest proposal put forward by the European Commission, which was summarily rejected by a resounding majority of the Greek electorate (61 per cent). Despite such overwhelming popular resistance against austerity, Tsipras ended up accepting the even harsher terms of a heavily front‐loaded, cash‐for‐reforms, third Greek bailout package only a week later on 12 July 2015 and then went on to have it ratified in a very heated parliamentary session, in which the anti‐euro left wing of his parliamentary party splintered off. In light of these cataclysmic developments, Tsipras announced a snap election in September 2015, which SYRIZA won quite handily – seeing only infinitesimal losses in its vote share (36 per cent) – notwithstanding the worsening economic conditions, the renewed austerity and the fact that the government had by its own admission failed to carry out the express will of the Greek people and its own promises before the referendum.

We surmise that input‐oriented voting behaviour – focused on questions of equity and national identity – was key in getting the SYRIZA government back into office by bolstering support for an incumbent prime minister (PM) who came across as a trustworthy representative of the people. Instead of focusing on his government's prior policy achievements, Tsipras effectively ran a campaign that triggered and reinforced those exact voting mechanisms of input‐based accountability by emphasizing the systemically constrained policy environment, the ‘moral high ground’ of the left and the fact that SYRIZA represented the uncorrupted ‘fresh face’ of Greek politics. In light of the party's class‐based rhetoric, one may also link input‐oriented sources of accountability to the demand for descriptive representation, defined as the degree to which elected representatives share the characteristics of the represented.

The turbulent events of 2015 in Greece showcase the limits of economic policy‐making and the ineffectiveness of brinkmanship politics in a heavily constrained environment of political and economic integration that limits the range of available policy options and renders choices starker and signals less noisy (Jurado et al., Reference Jurado, Walter, Konstantinidis and Dinas2020). As a result, the Greek case amounts to an apposite ‘extreme‐conditions’ natural experiment for the study of political accountability and economic voting in the face of broad globalization‐induced policy constraints. By the same token, the Greek political environment at the time makes for an exemplary case of ‘input clarity’ as the government's intentions and negotiating strategy were making headlines on a daily basis. This combination also defines the scope conditions of our argument on input‐oriented voting: Input accountability should work best when inputs are clear, while outcomes remain ambiguous.

Research design

We test our argument against a nationwide, computer‐assisted phone survey conducted in the run‐up to the 20 September 2015 Greek parliamentary election. The survey was run by the University of Macedonia's Research Institute of Applied Social and Economic Studies in Thessaloniki, Greece, on 7–8 September 2015 and comprised 1018 respondents identified through a multi‐stage sampling process.

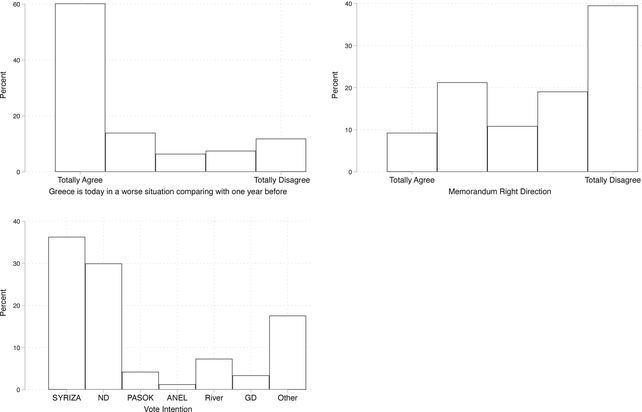

We start by providing an empirical illustration of the research puzzle presented above, namely, the fact that Greeks re‐elected a government that arguably had a disastrous record in office and ended up signing a bailout package whose conditions had been previously rejected in the July 2015 referendum. The first graph in Figure 2 shows that the vast majority of our respondents held a negative evaluation of the government's economic record, with more than 70 per cent of them stating that the economic situation was worse than a year earlier. The second graph shows that a plurality of respondents thought that the economic situation was not only worse at that time but also amounted to an unnecessary sacrifice for a better future. When asked whether they thought that the constraining conditionality provisions contained in the memorandum of understanding were in the right direction, 60 per cent of our respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. Finally, the third graph confirms that despite the negative of the government's record, the overall economic situation, and the July 2015 bailout agreement itself, the party with the highest voting intention was SYRIZA, thus foreshadowing the party's electoral victory 2 weeks later. These findings highlight the paradox we intend to shed light on.

Figure 2. The empirical puzzle (Source: own survey data).

We propose input‐oriented voting as a valid explanation of this puzzle: Voters rally against those supranational constraints that undermine the incumbent's effort to shift the status quo towards a more desirable direction. The relevant input here is the perception that the government had done everything possible to challenge the status quo and achieve a positive result in the bailout renegotiation, whereas the relevant outcomes amount to the content of the final bailout agreement, the continuation of fiscal consolidation policies and the overall effects of austerity on the economy. Although the outcome of the negotiation was clearly negative for most voters and amounted to a clear breach of the government's pre‐electoral promises, government officials repeatedly claimed that they were trying really hard to get a better deal. We argue that the incumbent's subsequent electoral success was rooted in the fact that they were effective at distinguishing between inputs and outcomes, thereby deflecting the blame for the negative, growth‐sapping aspects of the new bailout agreement to factors beyond their control, namely the intransigence of the country's creditors and the structural flaws of the Eurozone. By assuming responsibility for inputs and using failed outcomes as a justification for the need for more action, they managed to escape the electoral defeat that usually awaits governments presiding over economic crises.

To test our theory, we designed an experiment embedded within the survey, whereby we randomly assigned respondents to four different groups. Unlike the control group, all three treatment groups received some prompting statement (cue) about the government. The second group was informed of the failed outcome of the government's renegotiation strategy but not of its effort to overturn the status quo. The third group was primed about the government's exerted effort to reverse the austerity content of the prevailing agreement but not about the unsuccessful renegotiation outcome. Finally, the combined cue for the fourth group emphasized both the government's effort and the failed outcome of the government's attempt at reversing the status quo. More specifically, respondents received the following prompting statements by group:

(i) Control group: None.

(ii) Failed‐outcome treatment group: After 7 months of government, outgoing Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras did not improve the position of Greece towards its lenders.

(iii) Effort treatment group: After 7 months of government, outgoing Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras seems he did everything in his hands to improve the position of Greece towards its lenders.

(iv) Effort‐cum‐failed‐outcome treatment group: After 7 months of government, outgoing Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras seems he did everything in his hands to improve the position of Greece towards its lenders but without success.

We analyze the experiment in three parts. In the first part, we study responses to the vote intention question that followed in the survey after the treatments. All respondents were asked, ‘How likely are you to vote for SYRIZA? Please answer using a scale of 0 to 5 where 0 means “not at all likely” and 5 “very likely”’. Thus, our key dependent variable here is vote intention, which we regress on our three treatments. In the following section, we present the estimated treatment effects with and without the covariates of sex, education, region and income (all in fully factorized form) in order to examine the sensitivity of our estimates.

In the second part, we explore variation across different types of voters. As argued above, input‐oriented voting should be more prevalent among those who have a stronger belief that supranational constraints circumscribe outcomes and perceive themselves and their country as victims of globalization. To that effect, prior to the survey experiment, we asked our respondents how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement, ‘Greeks have suffered more than people from other countries’, as a proxy for their overall sentiment of victimhood and injustice done by the global economic system. We expect higher levels of perceived victimhood to be associated with a more input‐oriented approach to voting.

Finally, we shift our attention to other response items in order to delve into the theoretical mechanisms driving our main treatment effects and thus to decompose the ingredients of input‐oriented voting. As discussed in the theoretical section, input‐oriented voting is associated with three characteristics: (a) an emphasis on effort, (b) an attribution of outcomes to external factors and (c) the use of information about the government's inputs and outcomes to update one's beliefs over politicians’ traits and attributes. We try to unpack these components by using the following series of questions:

(a) To gauge whether voters actually changed their perceptions of the incumbent's effort after the treatments, we asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the following two statements: (i) ‘The government has fought as hard as it could against the creditors’, and (ii) ‘The government has defended the pride of the Greek people.’ If our reasoning is correct, respondents receiving a cue emphasizing incumbent effort should agree more with both statements.

(b) We used two response items as measures of responsibility attribution. The first question was, ‘Which one of the following is primarily responsible for today's situation: the current SYRIZA government, the previous PASOK and New Democracy governments, the Troika or Germany?’ We create two different dichotomous variables that capture whether respondents held SYRIZA (1 if SYRIZA is held responsible, 0 otherwise) or external actors (1 if Troika or Germany are held responsible, 0 otherwise) responsible. The second question asked respondents if they agreed or disagreed with the statement, ‘The government was responsible for the bank closures in the run‐up to the July bailout referendum’. We expect respondents within the combined treatment group to have been more likely to attribute responsibility to external actors than to SYRIZA. In other words, the treatment should have triggered the realization that supranational constraints make governments less responsible for outcomes.

(c) We tried to tap into perceptions about the incumbent's attributes with two survey items. Both were based on the idea that respondents would use the available information (unsuccessful effort to reverse the status quo of austerity) to create counterfactuals. The items read as follows: ‘If Tsipras gets re‐elected, he will manage to renegotiate a debt haircut next year’ and ‘The government has secured a better deal for Greece with its creditors than other parties could have done’. As with all previous items, (dis)agreement with these statements was measured on a scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree') to 5 (‘strongly agree'). To enable comparisons across outcomes, we standardize all items and thus present standardized beta coefficients in our results section.

Results

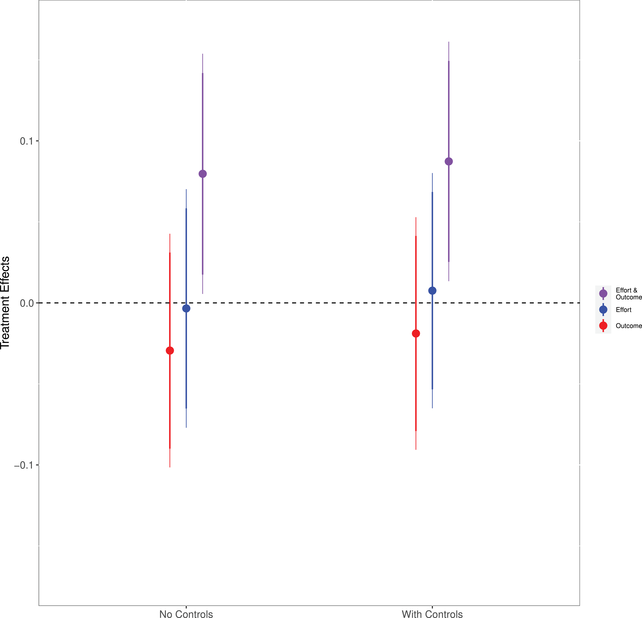

Figure 3 illustrates the results of the first part of the experiment. We present the results in two columns corresponding to two different specifications: one with and one without the covariates. The similarity between the two columns simply confirms our intuition that, given randomization, the inclusion of the covariates does little to change our treatment‐effect estimates. In each column, each treatment group is compared to the control group. The first entry displays the impact of the failed‐outcome treatment and shows that our respondents’ vote intention for SYRIZA was not affected by priming on the government's lack of success in the negotiations. In principle, this is in line with the standard model of voting in a globalized environment, whereby awareness of governments’ limited room to manoeuvre induces voters to place less emphasis on final outcomes (Hellwig, Reference Hellwig2001). Governments are not punished for bad outcomes simply because they are subject to binding supranational constraints.

Figure 3. Treatment effects on vote intention for SYRIZA. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: All bars denote the effects and the accompanying 90 per cent (thick line) and 95 per cent (thin line) confidence intervals for each treatment. Estimates are presented as standardized beta coefficients.

The second entry denotes the isolated effect of the singular effort (input) treatment and shows that there was also no significant impact on vote intention when emphasis was solely placed on the effort exerted by the government throughout the negotiation period. We did not have a strong prior expectation about the effect of this treatment as we premise our argument on the assumption that voters have a clear indication that their government is constrained and that it cannot sway outcomes.

Finally, the last entry presents the combined treatment effect of effort and failed outcome. In line with our expectations, priming respondents on SYRIZA's failed effort made them more likely to express support for the incumbent. The treatment effect is non‐trivial in magnitude. Following the interpretation proposed by DellaVigna and Kaplan (Reference DellaVigna and Kaplan2007), the combined treatment ‘persuaded’ 7 per cent of respondents to vote for SYRIZA. As per our theoretical argument, the mismatch between inputs and outcomes presumably signalled to voters that domestic economic outcomes were mostly due to systemic factors. Otherwise put, the combined treatment cue proved to be informative about the difficulty of the task at hand. It must be noted that the effort‐cum‐failed‐outcome treatment effect is significant compared not just to the control group but also to the other two treatment groups (see Table A.2 of Online Appendix A for this comparison). The combined treatment seemed to impart increasingly more refined information to our respondents that allowed them to form more precise posteriors over the policy environment at the time of the September 2015 election. Our prompting statements essentially contained an informational signal about the government's limitations in achieving what it had intended to. They helped our respondents update their priors about the binding nature of supranational constraints and the feasibility of the government's electoral mandate. The more convinced they became of the inexorability of extraneous policy constraints and the dictates of global capitalism, the more likely they were to reward representative policy inputs.

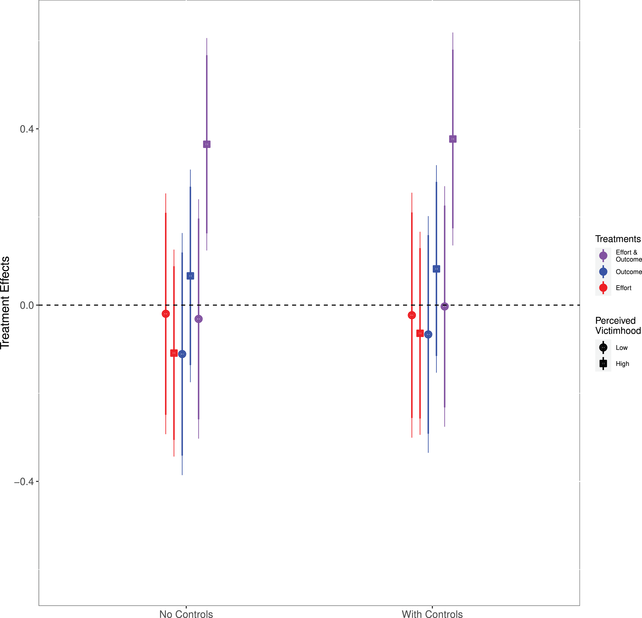

As a next step, we engage in a more fine‐grained analysis of the theoretical underpinnings of our findings. If these results are due to input‐oriented voting, we should also observe some additional corroborating patterns. We start with an analysis of heterogeneous treatment effects. Some voters were presumably more likely to interpret the treatment as evidence of the policy ‘straitjacket’ imposed on the government, whereas others arguably still believed that the government could be held responsible for outcomes. To tap into this, we test whether voters with stronger feelings of victimization were more likely to move towards input‐oriented voting, regarding outcomes as less informative. Accordingly, we distinguish respondents with respect to their level of agreement with the claim that Greeks have suffered more than other people. We combine those who agreed (19.58 per cent) or strongly agreed (41.35 per cent) against all other respondents (39.07 per cent). The heterogeneous treatment effects by the level of perceived victimhood are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Treatment effects on vote intention for SYRIZA by the level of perceived victimhood. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Circles denote the estimates among those who strongly or mostly agree with the victimhood statement and rectangles refer to the rest of the sample. Estimates are presented as standardized beta coefficients with 90 per cent (thick line) and 95 per cent (thin line) confidence intervals.

Comparing the two columns of the graph, the results are once again very similar with or without the covariates. We find that those who agreed or strongly agreed with the victimhood item were more responsive to the combined treatment. Priming them with a negative outcome, together with information about the government's effort, increased their likelihood of voting for SYRIZA by 15 percentage points. This was the group expected to be most sceptical towards globalization. We find no effect, however, among those who did not agree with the victimhood statement. More importantly, perceived victimhood seemed to exert a significant moderating effect only on those receiving the combined treatment as opposed to the singular effort (input) or outcome treatments.

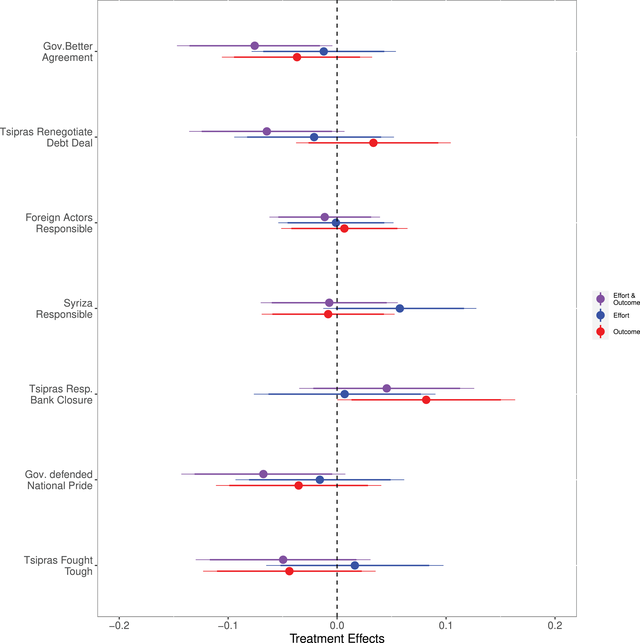

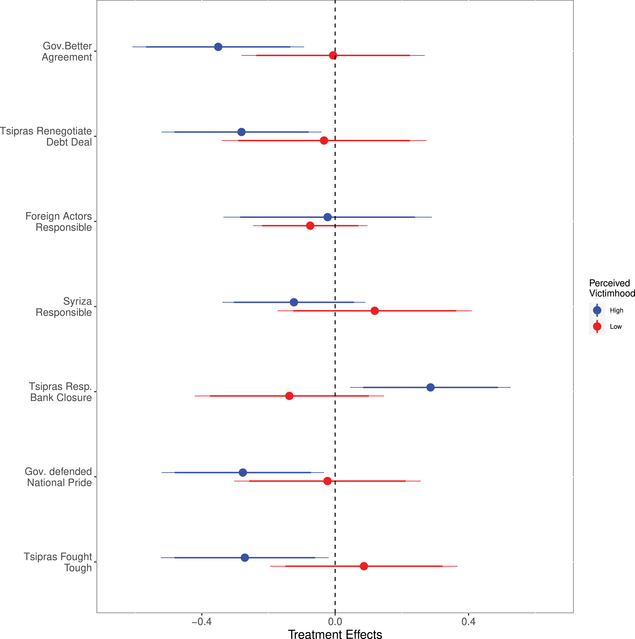

We now proceed to test for the various theoretical mechanisms by estimating treatment effects on responses to a series of statements that proxy for the components of input‐oriented voting. The first two survey items, ‘Tsipras fought hard’ and ‘The government has defended national pride’, are used to emphasize effort. By way of a manipulation check, they allow us to capture whether voters are indeed focusing on inputs, and not some different issue when assessing the incumbent. The next three items, ‘SYRIZA is responsible for Greece's financial situation’, ‘Foreign actors are responsible for Greece's financial situation’ and ‘Tsipras is responsible for the bank closures’, are used to tap into responsibility attribution by distinguishing between the incumbent government and external actors. Our argument is that input‐oriented voting should also comprise blame exoneration over outcomes, especially when voters believe that outcomes are not affected by what governments try to do. This is exactly the reason why we find a significant effect only for the combined treatment in the first part of the experiment. The last two items are meant to reflect voter perceptions of the incumbent's qualities, namely their willingness to renegotiate the debt in the future and their capacity to reach a better agreement relative to other political parties. The evaluation of these statements captures the degree to which our respondents perceived inputs as informative signals of what the incumbent would be willing to do in the future and of their true traits. According to the logic of input‐oriented voting, elections become less of a retrospective exercise and more of a screening process for selecting trustworthy and representative candidates.

Figure 5 presents the results. of All variables range on a scale from 1 (‘strongly agree') to 5 (‘strongly disagree'). Hence, a negative marginal effect indicates agreement with the statement. Although the results are less consistent than in the previous analyses, taken altogether they point to the expected direction. First, we find that the combined effort‐cum‐failed‐outcome treatment increased the likelihood of agreeing with the statement that Tsipras had fought hard to reverse the status quo (although the effect is similar in magnitude to the effect of the outcome alone). In other words, there is suggestive evidence that the combined treatment did indeed change our respondents’ perception of the incumbent's effort. In addition, the item about the extent to which the government had defended national pride had an even stronger effect on our respondents’ perception of effort.

Figure 5. Treatment effects on different dimensions with the accompanying 90 per cent (thick line) and 95 per cent (thin line) confidence intervals. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Second, the evidence for the responsibility attribution argument is less clear‐cut: The combined treatment seemed to induce our respondents to disagree with the statement that Tsipras should be held responsible for the bank shutdown (although this effect does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance). In a way, being reminded about the failed outcome alone seemed to have a stronger effect in this case. The evidence is more ambiguous when it comes to who was to be blamed for the country's overall economic state of affairs. Third, the corroborating evidence in regard to the two response items about incumbent qualities is more concrete. In both cases, there was a clear effect of the combined treatment on our respondents' propensity to agree with the statements that the government – and the PM in particular – brought a better deal than what the opposition could have brought and that the former were more likely to achieve a future deal on the national debt. Thus, taken as a whole, these results seem to validate the input‐oriented voting argument that information about government intentions and final outcomes helps update one's beliefs about politicians' true attributes.

Furthermore, we combine the two previous sets of analysis and examine the impact of the combined treatment on the same outcomes as in Figure 5 for different levels of perceived victimhood. As illustrated in Figure 6, the combined treatment exerted a significant effect on the recognition of incumbent effort, in terms of significantly higher levels of agreement with the statements about how Tsipras had fought hard to change the status quo and how the Greek government had defended national pride among them, only among those who registered high levels of perceived victimhood. Likewise, we find that our previous results regarding the impact of the combined treatment on perceptions of the incumbent's qualities were primarily driven by highly victimized treated respondents who exhibited a higher propensity for agreeing with the statements that Tsipras would be able to renegotiate the national debt and that the government had achieved a better deal. Finally, we also find a strong effect of the combined effort‐cum‐failed‐outcome treatment on the blame exoneration of Tsipras for the bank shutdown among respondents with high levels of perceived victimhood. On average, the combined treatment seemed to ‘persuade’ at least 10 per cent of respondents with high levels of victimhood that the incumbent had tried hard, that the PM was not responsible for the bank holiday and that the government had already delivered and would continue to deliver better outcomes than the opposition. In sum, input‐oriented voting mechanisms appear to be more prevalent among highly victimized respondents, while the same effects vanish among those with low levels of perceived victimhood.

Figure 6. Effects of the combined effort‐cum‐failed‐outcome treatment on different dimensions by the level of perceived victimhood. All bars denote the effects and the accompanying 90 per cent (thick line) and 95 per cent (thin line) confidence intervals. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

These are all key results that are in line with our theoretical argument on input‐oriented voting. When the combined statement on the effort and failed outcome was primed, attention seemed to be placed only on inputs insofar as they informed voters of the characteristics of the incumbent. Rather than causing a decline in the incumbent's evaluation, statements about the incumbent's failed attempt to reverse austerity seemed to operate as an informative signal of the difficulty of the renegotiation task in the context of a systemically constrained environment and Tsipras' steadfast resolve to improve economic conditions in the near future. The combined treatment reinforced expectations that Tsipras would manage to negotiate a debt haircut within the following year and that he would strive not to follow through with the agreed austerity measures. These prospective assessments might also help to explain the puzzling increase in vote intention for SYRIZA as documented above. Finally, our heterogeneous treatment analysis suggests that these input‐oriented voting effects were primarily driven by respondents who exhibited a high level of perceived victimhood.

Discussion

The trade‐offs of globalization, triggered by a combination of economic, political, and public health crises – as in the crisis‐ridden era following the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 or the current context of the COVID‐19 pandemic – have seemingly altered the nature of political accountability and democratic legitimacy. Market integration, factor mobility and the rise of supranational governance have obfuscated the straightforward logic of economic voting by blurring the links between democratic inputs and outcomes and confounding the mechanisms of responsibility attribution. Authors in this strand of the literature have shown that the salience of the economic dimension of political contestation has subsided and that voters have shifted their attention to other post‐material dimensions of electoral competition in order to form consistent political preferences and mechanisms of partisan identification. And yet, in the context of acute economic volatility, as long as the locus of democratic politics remains at the national level, one may not convincingly argue that the traditional economic dimension no longer has any bearing on our understanding of voting behaviour.

While globalization has been shown to limit the scope of the canonical model of retrospective voting, the literature has not yet fully developed an alternative account of voting behaviour in a constrained policy environment. This paper has sought to address this gap from a theoretical and an empirical standpoint by highlighting the distinct nature of input‐oriented voting in the context of broad policy constraints stemming from political integration and/or economic globalization. We use experimental evidence (drawn from a survey conducted in the run‐up to the September 2015 Greek parliamentary election) to show that mundane issues, such as the economy and material well‐being, still matter for voting but in different ways than previously shown. In Online Appendix B, we further probe the external validity of our findings through a panel of EU member states.

First, our empirical evidence suggests that perceptions of international constraints induce voters to place more emphasis on the incumbent's original intentions than the actual policy outcomes they end up delivering and that failed attempts to alter the status quo may in fact be evaluated positively. In such a context, voters will tend to assess inputs in addition to outcomes. This input‐oriented voting logic is particularly prevalent among those voters who feel victimized by the ‘golden straitjacket’ of globalization. In other words, our voting mechanism is premised on pessimistic attitudes of victimhood, according to which voters believe that as long as their country's fate is dictated by the extraneous and inscrutable forces of economic globalization and political integration, no politician can truly better their lot no matter how competent they might be.

Second, we have tried to identify and unpack the underlying mechanisms of input‐oriented voting by demonstrating that voters may reward an unsuccessful incumbent on the basis of updated beliefs about the incumbent's true type and prospective assessments about what they will try to do in the future. When voters believe the range of feasible policy outputs and corresponding policy outcomes to be circumscribed by supranational constraints, they are more likely to reward an incumbent proven to be incapable of changing the overall policy framework or bringing about positive economic outcomes as long as they perceive the incumbent to be congruent, trustworthy and willing to keep defending their interests at all costs. Our findings thus highlight another interesting paradox: Efforts and actions aimed at overturning an unpopular policy mix are more likely to trigger input‐oriented voting and support for the incumbent the more they are perceived as inconsequential.

In that regard, the Greek ‘perfect‐storm’ scenario allows us to shed light on the same cognitive voting mechanisms that got Trump elected and ‘Brexit’ decided, fully refracted through the prism of a survey experiment. Trump's ‘Make America Great Again’ rhetoric boosted his electoral support from an underprivileged class of mostly white voters that felt victimized by the vagaries of unbridled globalization in the form of trade and migration flows. Despite his ineffective handling of the pandemic, he ended up increasing his vote total from the 2016 to the 2020 presidential election. He managed to do so by antagonizing Congress and deflecting the blame for the deleterious effects of the pandemic to external actors (such as China or the World Health Organization), thereby playing to his base and portraying himself as a trustworthy and responsive leader whose executive power was being chipped away by the ‘deep state’ and the inscrutable forces of globalization. In a similar vein, the Brexit campaign – disregarding a long period of sustained economic growth under EU membership – was centred around the slogan of ‘taking back control’ and reclaiming national sovereignty that had been purportedly usurped by the EU's unaccountable bureaucracy and its headstrong push towards deeper political integration. In that light, the results of our paper arguably help refine our understanding of voting behaviour – as well as populist attitudes – in the modern era of economic globalization and political integration.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Stefanie Walter (University of Zurich) to the design of the survey experiment and her overall input into the project. They also thank discussants and conference participants at the CESifo 2018 Venice Summer Institute, the University of Geneva, the University of York, the Instituto de Políticas y Bienes Públicos, CSIC (Madrid, Spain), the 15th Conference on Research on Economic Theory and Econometrics (C.R.E.T.E.) (Tinos, Greece), the Sixth Annual Conference of the European Political Science Association (Brussels, Belgium), and the Erasmus Political Economy Workshop (Rotterdam, the Netherlands), as well as journal reviewers, for their invaluable comments and insights. Furthermore, Nikitas Konstantinidis wishes to acknowledge funding support from the Department of POLIS, University of Cambridge, and Ignacio Jurado wishes to acknowledge funding support from the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness (grant CS02017‐82881‐R), and the Ramón y Cajal Fellowship.

Funding Statement

This article was written as part of the research project “Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness of Spain (grant CSO2017‐82881‐R)”.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: