Introduction

Medieval mining towns in Europe developed as centres of mining regions, hubs of innovation, capital flows and social change. They acted as the interface between political power and the global economy, engaging with local environments and causing long-lasting environmental impacts. These towns exemplified the interweaving of society and nature, where local actions were linked to a broader global context. Moreover, medieval mining towns were amongst the birthplaces of capitalism and its extractive principles. Consequently, they contributed to shaping a new European mindset that, over time, helped foster the development of the Anthropocene.

Studies of mining towns form part of the wider field of mining history, usually concentrating on economic, technological or social viewpoints (e.g. Blanchard Reference Blanchard2001; J. Kořan Reference Kořan1950; Małowist Reference Małowist2006; Molenda Reference Molenda1963; Westermann Reference Westermann and Westermann1997). A far more holistic approach emerged with the development of mining archaeology, which examines mining and metallurgical technology, environmental effects and the spatial and social organization of settlements and communities (Asmus Reference Asmus2012; Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Geltner, Aniceti, Buonincontri, Dallai, Tommolini, Viva and Volpi2024; Derner Reference Derner2018; Hemker Reference Hemker, Brather and Dendorfer2023; Hrubý Reference Hrubý2024; Minvielle Larousse Reference Minvielle Larousse2023). This advancement provided new insights into the role of mining in environmental change, mainly deforestation and pollution (Kaiser et al. Reference Kaiser, Tolksdorf, de Boer, Herbig, Hieke, Kasprzak and Kočár2021; Reismann Reference Reismann2022; Tolksdorf et al. Reference Tolksdorf, Elburg, Schröder, Knapp, Herbig, Westphal, Schneider, Fülling and Hemker2015; Tolksdorf Reference Tolksdorf2018). Changes in technology and environmental impact became linked with the development of mining ideologies and perceptions of nature (Asmussen Reference Asmussen2020; Smith Reference Smith and Valleriani2017). Within this range of topics, mining towns have attracted substantial interest in local history and archaeology, leading to numerous monographs (Hoffmann and Richter Reference Hoffmann and Richter2012; Molenda Reference Molenda, Kiryk and Kołodziejczyk1978; Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000). Nevertheless, few efforts have been made to synthesize the subject of mining towns (Cembrzyński Reference Cembrzyński2017; Kaufhold Reference Kaufhold, Kaufhold and Reininghaus2004; Molenda Reference Molenda1976). However, we still lack a comprehensive understanding of how these towns operated as socio-ecological systems, and how mining activities, political control and capital flows related to environmental change.

In this paper, I propose an ecological perspective to understand medieval mining towns. Ecology is a broad field that examines the relationships between living organisms, their environments and the flows of resources, energy and information. It analyses patterns and processes within socio-ecological systems to understand how changes arise through interactions between humans and nature. Here, I applied ecological concepts to show how flows of matter, energy and information generate feedback that leads to tipping points in the history of a mining town. I draw upon insights from human and political ecology to connect environmental processes and landscape change with social hierarchies and decision-making.

The main questions guiding this paper are: how are power structures embedded in medieval mining, and how does this shape human–environment relations? How did flows of ores, capital, energy and people generate feedback that shaped landscapes and urban communities? To explore these questions, I develop an ecological framework and apply it to a case study of Kutná Hora, one of Central Europe’s most significant medieval mining centres. Drawing on archaeological, geological and historical evidence, the study reconstructs the flows and accumulations that shaped its emergence, prosperity and decline.

The paper begins with the conceptual foundations of the ecological approach and its importance for historical studies. It then defines mechanisms of change, flows, stocks, feedbacks and tipping points that link social and environmental processes. Finally, it illustrates how these mechanisms function in practice through a case study.

Ecology – definitions, concepts, applications

Ecology offers a framework for understanding how humans and the environment interact through the flows of energy, matter and information. When applied to mining towns, this ecological framework helps us see how ore extraction, capital circulation and labour regulation create feedback loops connecting the physical environment with social hierarchies. Mining towns were highly complex and dynamic places. Due to global demand for metals, they could quickly attract large numbers of people from distant areas and diverse social backgrounds. As sources of revenue for rulers, they enjoyed legal and economic privileges that gave them an advantage over other towns. However, their existence heavily depended on the risks of mining activities, available resources, technological advances, global commodity prices and political agendas. Spatially, they had specific layouts and often existed in highly altered and polluted environments (Cembrzyński Reference Cembrzyński2017; Kaufhold Reference Kaufhold, Kaufhold and Reininghaus2004; Lampen and Schmidt Reference Lampen and Schmidt2014; Molenda Reference Molenda1976; Ratkoš Reference Ratkoš1974; Szende and Szilágyi Reference Szende, Szilágyi, Czaja, Noga, Opll and Scheutz2019). Therefore, they require a new approach that links different geographical scales and hierarchies. The strength of ecology lies in its relational perspective. Every change, whether small or large, local or global, triggers a series of interactions that connect humans and non-human elements within a single, intertwined socio-ecosystem. Viewing a mining town this way involves tracing these changes and understanding how they originated through accumulations, flows and tipping points. The ecological perspective provides a language to describe the entanglement of matter and mind that shaped medieval landscapes and ultimately offers insights that can be further tested with new data.

Development of ecology

Ecology has evolved from being solely biological to becoming a broadly used metaphor for relations within systems. Initially, it concentrated on relationships between organisms and their environments (van der Valk Reference Van der Valk, DeLaplante, Brown and Peacock2011). The turning point came with the adoption of systems thinking, viewing the environment as an ecosystem, which means a set of biotic and abiotic elements and their mutual interactions within a specific area (Tansley Reference Tansley1935). Building on that, ecology now analyses flows of energy and matter, metabolism and how ecosystems respond to disturbances (resilience) (Chapin III, Matson, and Vitousek Reference Chapin, Matson and Vitousek2011, 9; McIntosh Reference McIntosh1986). This shift towards system analysis allowed for the transfer of ecological thinking beyond biology. The idea emerged that ecological principles can be used to analyse human-dominated systems.

Human ecology developed when scholars recognized the important role of human culture and society in ecosystem dynamics. It studied adaptation strategies, energy use, resource management and settlement practices, often to tackle modern environmental challenges (Albiol and Lombardía Reference Albiol and García Lombardía2024; Borden Reference Borden2014; Dyball Reference Dyball, Harris, Brown and Russel2010; Dyball and Newell Reference Dyball and Newell2023; Haberl et al. Reference Haberl, Fischer-Kowalski, Krausmann and Winiwarter2016; Marten Reference Marten2001). It especially highlighted how humans and the environment are interconnected, affecting each other through flows of matter, energy and information, as seen in the landscape.

A challenge for ecology is urban areas. Initially, researchers focussed on ‘ecology in cities’, examining the impact of urban areas on the environment. Further developed ‘ecology of cities’, which examines land composition, form, density, heterogeneity and connectivity, as well as the distribution of people and functions, power structures, centralization and resource flows, all conceptualized as urban metabolism (Alberti Reference Alberti2008; Collins et al. Reference Collins, Kinzig, Grimm, Fagan, Hope, Wu and Borer2000; Douglas et al. Reference Douglas, Goode, Houck and Wang2011; Golubiewski Reference Golubiewski2012). This approach is particularly important for studying historical urban forms, as it shows how the built environment links local and global spheres, where all metabolic flows are accumulated and processed and the social sphere, which encompasses human hierarchies, the economy and knowledge, all of which regulate these flows.

Systems, feedback and flows

Ecology introduced several concepts crucial to understanding mining towns: socio-ecological systems, feedback, flows and stocks. A mining town is a socio-ecological system: a complex, integrated system that includes both social and ecological components, which interact dynamically across multiple scales (Biggs et al. Reference Biggs, Clements, De Vos, Folke, Manyani, Maciejewski, Martin-López, Preiser, Selomane, Schlüter, Biggs, De Vos, Preiser, Clements, Maciejewski and Schlüter2022; Preiser et al. Reference Preiser, Biggs, De Vos and Folke2018). Its components interact nonlinearly: a small change, such as discovering ore, can lead to a significant effect, such as the formation of a town. From these interactions, new qualities can emerge, for example, the development of a distinct social class of workers resulting from the interplay of the deposit’s structure, economic arrangements and technology. Consequently, predicting how the system will evolve solely on the basis of individual elements is impossible; only their interactions determine outcomes. Moreover, the system can adapt to new challenges owing to its internal structure. For instance, a mining town can overcome technical difficulties in mining by implementing new technologies and adjusting its financial and organizational arrangements. Finally, the system is open; it can influence distant areas and be affected by external factors. In this context, a mining town impacts forest cover in remote regions by importing fuel and timber, whilst global metal prices influence it; a decline in prices can render the town’s economy unprofitable.

The concepts of feedback, flows and stocks further explain how relationships within a system operate (Dyball and Newell Reference Dyball and Newell2023; Marten Reference Marten2001). A stock is a material or non-material thing that can accumulate. The level of stock changes due to flows. These flows can be physical, such as the flow of silver in mines, or metaphorical, such as the transfer of energy, wealth or feelings. Changes in stock value can trigger feedback. Feedback is an influence that occurs when a change in one element causes changes in other interconnected elements. Subsequently, the modified element can ‘feedback’ on the initial element, creating a feedback loop and impacting other elements. There is (1) positive (reinforcing) feedback, which amplifies change, and (2) negative (balancing) feedback, which resists change. An example of a positive feedback loop in a mining system is an increase in population, leading to higher production. Negative feedback involves technological issues that limit available income, thereby constraining the population that can sustain itself through mining. The relationship between stock accumulation and feedback illustrates how observed changes can be managed through human choices. For example, in a mining town, the declining timber supply can be offset by regulations that safeguard forests from overexploitation. However, some changes in stock can lead to a tipping point, a moment of significant transformation, such as the widespread decline in ore availability that forces mine closures. Tipping points often result from long-term accumulation and are therefore delayed. A good example is prolonged deforestation, which causes the breakdown of the local ecosystem.

Agency and hierarchies

Flows and feedback did not operate solely through natural processes, making the mining town a self-regulatory system. Whatever occurred there operated within legal norms and was mediated by power structures. Insights from political ecology are vital for understanding the socio-ecosystems of mining towns. Political ecology investigates hierarchies of power and decision-making in shaping environmental change, as well as the social inequalities that arise as a result (Morehart, Millhauser, and Juarez Reference Morehart, Millhauser and Juarez2018; Robbins Reference Robbins2012). In the case of mining towns, this perspective addresses questions about how mining was organized, who controlled it, who owned the capital and how the environmental impacts of mining were distributed.

Further insight into decision-making processes and changes in the mining towns brings the concept of relational agency. Ecology has assumed that human actions based on perceptions of environmental change are an inherent element of the ecosystem (Grimm et al. Reference Grimm, Morgan Grove, Pickett and Redman2000). However, the approach has recently shifted towards relational agency as being more embedded in the non-human environment (Christensen and Van Eetvelde Reference Christensen and Van Eetvelde2024; Gerrits Reference Gerrits2023). Agency, understood as the ability to cause change, is not an inherent feature, but results from a complex network of interactions between human and non-human elements. Local and global factors, the outcomes of past decisions, can converge to prompt actions that cause change (Crellin Reference Crellin2020, 165–172; Latour Reference Latour2005). Establishing a mine in a specific location is not merely a miner’s decision, but the result of global silver prices, technical knowledge, support from authorities and available capital. Nonetheless, significant changes rarely stem from individual decisions; instead, they emerge from accumulated practices. Hundreds of miners sinking shafts and bringing rock and ore to the surface collectively reshape the landscape. Consequently, the agency becomes part of the feedback loop within the mining town.

In this study, the medieval mining town is interpreted as a dynamic system where resource flows interact through feedback mechanisms. This system is self-organizing and politically regulated. Feedback operates through institutions, social norms and technological knowledge. This integration of systems thinking and political ecology enables the examination of relationships between social and environmental elements. Since this concept was initially developed to understand modern ecosystems and society, it now needs to be applied to research on historical mining towns.

Ecology in historical and archaeological research

Ecology has long been part of studies on past societies. The fact that ecosystem dynamics have historical dimensions and a focus on human–environment relationships naturally inspires archaeological and historical investigations. Since prehistoric archaeology has shifted towards examining the environment, ecology now holds significant influence in the discipline (Butzer Reference Butzer1982). The rise of environmental archaeology, geoarchaeology, palaeobotany and palaeozoology has greatly expanded opportunities for studying human ecology (Reitz and Shackley Reference Reitz and Shackley2012). This development has sparked increased interest in exploring socio-ecological systems through archaeology (Barton et al. Reference Barton, Ullah, Bergin, Mitasova and Sarjoughian2012; Crabtree and Kohler Reference Crabtree and Kohler2012). However, historical ecology remains most closely linked with ecology itself. It investigates long-term interactions between human societies and their environments, exploring how land use, resource exploitation and environmental change in the past have shaped current landscapes and ecosystems (Balee and Erickson Reference Balée, Erickson, Balée and Erickson2006; Crumley Reference Crumley and Crumley1994; Szabó Reference Szabó2015). Recently, advances in computational methods and the availability of ‘big data’ have brought about a new level of integration between archaeology and ecology (Crabtree and Dunne Reference Crabtree and Dunne2022). Both disciplines regard landscape as a central platform for analysis. Whilst archaeology often concentrates on the distant past, historical ecology focusses on the historical dimensions of more recent landscapes.

Unlike prehistory studies, the European Middle Ages have been dominated by historical narratives focussing on elites and politics, with little attention paid to developing theoretical models of ecological interactions (Schreg Reference Schreg2014). Nevertheless, many studies influenced by ecology originate from environmental history and historical archaeology. These range from rural landscapes in Sweden to issues of state formation, economic development, the resilience of past societies and the environmental impacts of crusades (Curtis Reference Curtis2014; Izdebski, Mordechai and White Reference Izdebski, Mordechai and White2018; Lagerås Reference Lagerås2007; Pluskowski, Boas and Gerrard Reference Pluskowski, Boas and Gerrard2011; Warde Reference Warde2006). Sadly, a clear definition of ‘ecology’ and its core principles remains elusive in historical research. Ecology is described as ‘multiple interactive factors that allow anthropogenic impact on the environment to be measured comparatively over time and space’ (Pluskowski et al. Reference Pluskowski, Brown, Banerjea, Hayward and Pluskowski2019). It has been used to prevent the division between humans and the natural environment, or is regarded as part of environmental history (Magnusson Reference Magnusson2013; Warde Reference Warde2006).

Several scholars have conceptualized medieval cities from an ecological perspective. Britta Padberg (Reference Padberg1996) applied system ecology and population ecology to medieval German towns, emphasizing demographic dynamics. Richard Hoffman (Reference Hoffmann and Squatriti2007, Reference Hoffmann2014) described urban metabolism, viewing cities as ‘sinks’ for energy and resources, shaping environmental footprints into hinterlands. His quantitative approach estimated timber, food and fuel use, revealing urban impacts and dependencies. However, it mainly focussed on numbers, overlooking political and social factors in resource access. Christophersen (Reference Christophersen2023) proposed a new approach to medieval urban ecology, conceptualizing the town as a social-ecological system whose elements are interconnected through social practices encompassing people’s attitudes, actions and the material outcomes of those practices. On the basis of examples from Bergen and Trondheim, he shows how changes in waste disposal practices reflect shifts in attitudes towards ecological conditions.

Ecology in historical research was mostly metaphorical, lacking practical solutions. Nevertheless, it highlights the most critical aspects of urban ecosystems. The key insight comes from Christophersen, aligning flows and accumulations with human relational agency. In the latter part, I propose a heuristic ecological model for mining towns, which provides a basis for further hypotheses and computational analysis.

Applying these concepts to the historical past is challenging but achievable. Different types of evidence can provide insights into flows, accumulations and hierarchies. Thanks to archaeological and cartographical data, we can observe the extent of mining fields and potential accumulations of waste and hazardous substances. Historical documents, cartographic analysis and palaeobotanical data can reveal changes in forest cover. Additionally, wealth accumulation and power relations are evident in the built environment, including the quality of housing and communal buildings. A variety of mining documents and historical narratives highlight key points and external influences. Naturally, the quality and detail of the data vary. Evidence of mining from early periods is particularly scarce, as much of it was destroyed by later mining activities. Nonetheless, it remains possible to identify the most important connections and diagram them to illustrate relationships. This approach generates hypotheses that can be tested with additional evidence and allows for comparative analysis across mining towns.

Ecology of a medieval mining town – case study of Kutná Hora

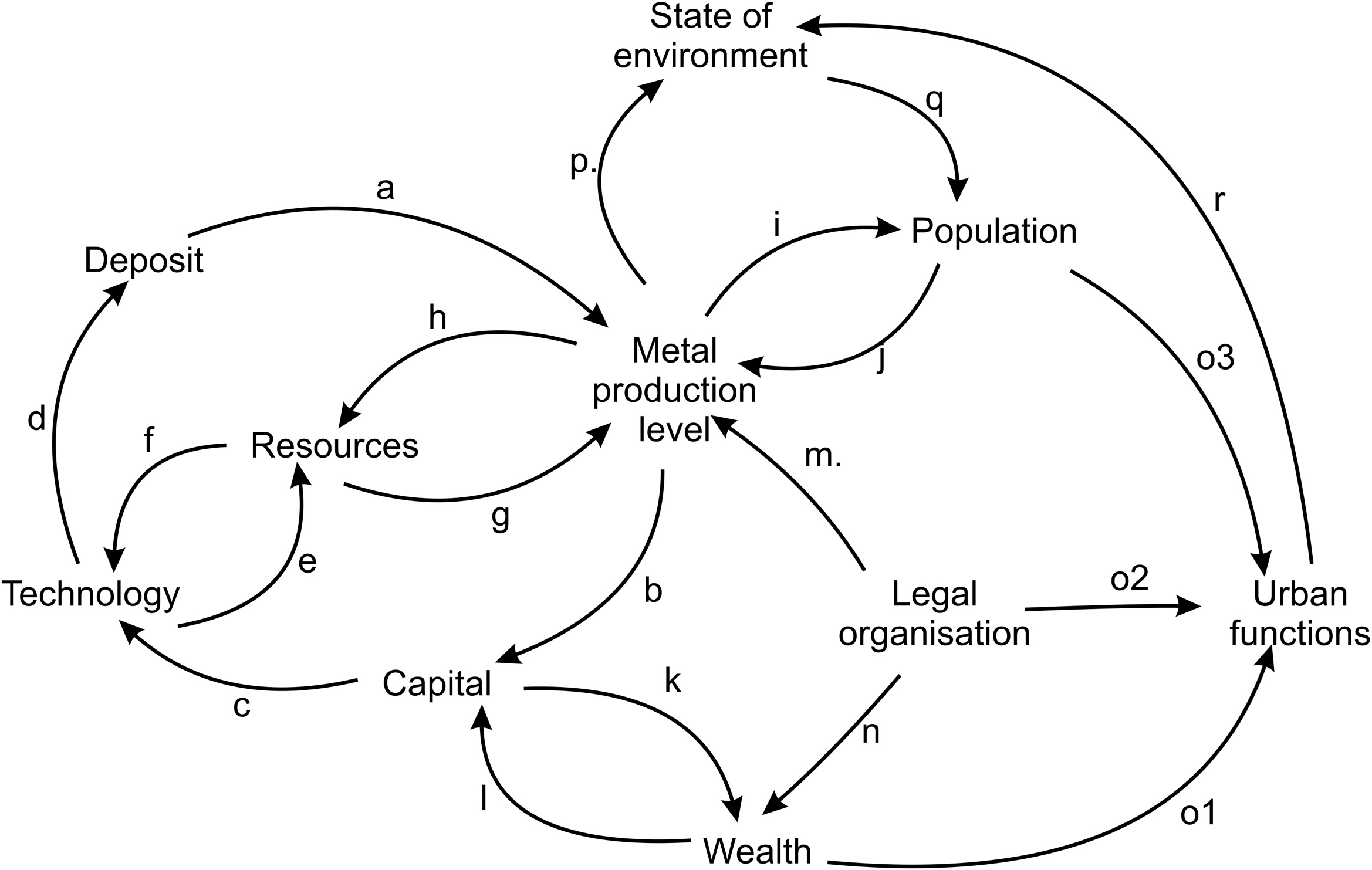

The case study presented below employs the ecological framework described earlier. It examines a socio-ecological system made up of interacting components: environment, technology, society and political hierarchies, which are linked through flows of matter, energy, people and information. It follows a sequence of analytical steps: (1) identifying stocks and flows; (2) recognizing tipping points; (3) detecting feedback loops between elements that could lead to tipping points; and (4) assessing the role of political institutions and hierarchies in governing the system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Assumed interaction within mining town socio-ecosystem: (a) flow of ore; (b) demand for capital; (c) investment in technology; (d) application of technology; (e) impact on resource base (e.g. forest); (f) altered resource base changes the technology; (g) more resources increase the production level; (h) increased production leads to greater resource consumption; (i) production level attracts people; (j) more people boost production; (k) invested capital is repaid and accumulates as wealth; (l) more wealth enables further investment; (m) control by a monopoly lord to sustain production; (n) monopoly lord shares profits; (o, 1–3) emergence of the town; (p) impact on the environment (erosion, pollution); (q) impact on the population’s quality of life; (r) additional environmental impacts through urbanization.

Kutná Hora (Czechia) was one of the most significant mining towns in Central Europe, developing directly from mining activities. To illustrate how different elements interact, this case study is structured diachronically, depicting the town’s life cycle from its birth.

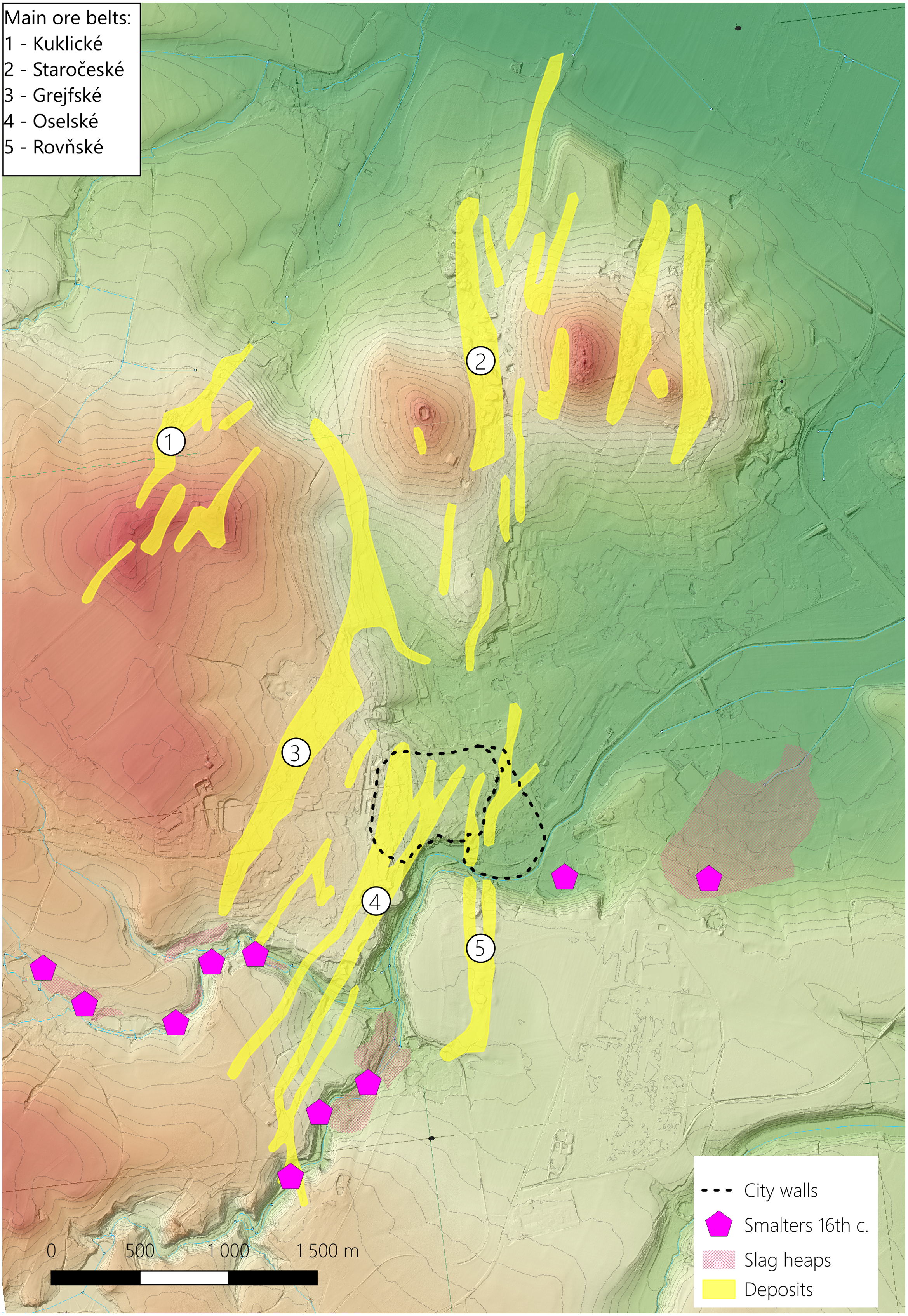

The deposit

The hydrothermal polymetallic deposits represent the initial stock. They covered an area of about 27 km2, located within the hilly terrain above the Vrchlice stream (Pach in the past), surrounded by hills to the north and west (Figure 2). The deposits consisted of elongated belts of main veins and rock impregnated with ore (Holub Reference Holub2018, 21). Hydrothermal deposits were not homogeneous; the mineral composition varies between veins and changes vertically, with much richer parts near the surface. In Kutná Hora, the northern part was rich in copper ores, the central part contained lead–silver ores, and the southern part was rich in antimony–silver ores. The silver concentration, a primary focus of mining here, varied with location and could reach 1kg/ton. Particularly rich were small shallow concentrations (Holub Reference Holub2018, 21–27). Most of the deposit, especially in the town area, was covered by a 10 m thick layer of clay (Absolon Reference Absolon2018, 11). Deposits, hilly landscapes, rivers and streams formed the environmental setting. Nonetheless, this environment was embedded within the land’s political structures, which controlled access and how the flow was initiated.

Figure 2. Kutná Hora – deposits and localization of the town. The extent of deposits is based on the Historical Town Atlas (Bartoš et al. Reference Bartoš, Novák, Posil, Vaněčková, Vaněk, Velímský and Žemlička2010).

Since the 12th century, all metallic minerals were under the king’s monopoly, and only he or those to whom he ceded his rights could grant mining concessions (Bartels Reference Bartels, Kim and Nagase-Reimer2013; Hägermann Reference Hägermann, Kroker and Westermann1984). Amongst those who gained part of this control were towns (Hrubý Reference Hrubý2024, 38). In the area described, it was Kolín and Časlav (Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000, 37). However, the land belonged to the Cistercian monastery in Sedlec (east of the town), which had further implications for the town’s spatial development. Nonetheless, power relations remained fixed, and to oversee the mining, the king needed to intervene; however, this occurred after the silver flow had begun.

Ore, technology and mining law

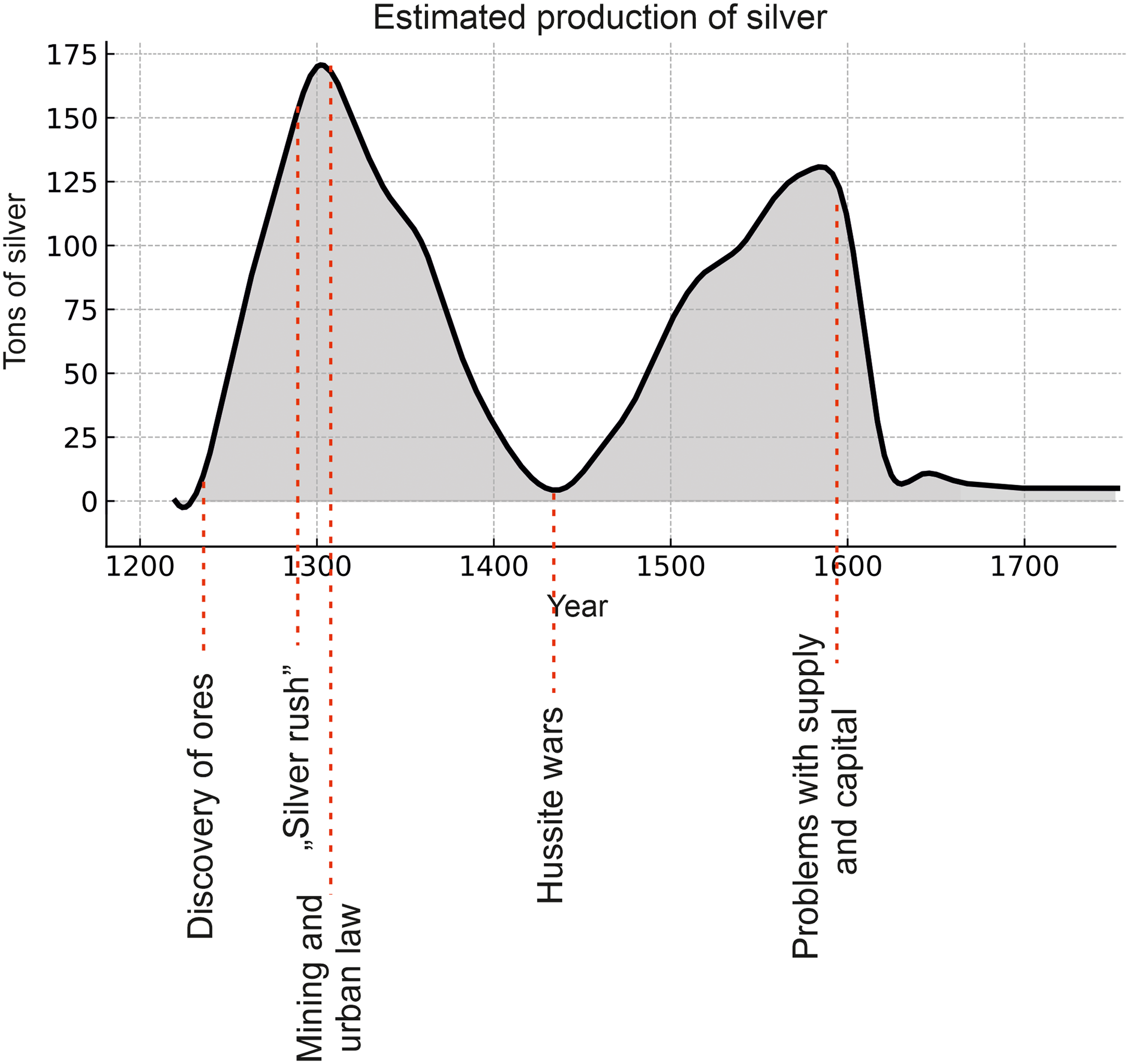

In the 13th century, the Kingdom of Bohemia experienced a surge in mining activities (Hrubý Reference Hrubý2024). Mining in the Kutná Hora area probably began before 1276 (Bartoš et al. Reference Bartoš, Novák, Posil, Vaněčková, Vaněk, Velímský and Žemlička2010, 3; Čechura Reference Čechura1979, 157; Kořan Reference Kořan1950, 4). The turning point occurred in the last decade of the 13th century with the discovery of a particularly rich part of the deposit, which led to an exceptional influx of people from 1294 onwards (Čechura Reference Čechura1979, 160). This was the first feedback; more people meant more ore. Estimated production levels suggest a peak just before 1300 (Figure 3) (Holub Reference Holub2018). However, reaching these levels required the use of proper technology.

Figure 3. Correlations between the level of silver production and tipping points in the town’s history (estimated production based on Holub Reference Holub2018).

When mining in Kutná started, the technology necessary to access ‘underground wealth’ was quite advanced (Asmus Reference Asmus2012; Molenda Reference Molenda1963, chap. VII; Scholz Reference Scholz and Kubenz2012; Wagenbreth and Wächtler Reference Wagenbreth and Wächtler1990, 55–71). In brief, the process began with multiple prospecting shafts. If ore was found, miners sank a shaft to access it. Following the ore deposits, miners constructed tunnels and chambers. Subsequently, shafts were interconnected to improve ventilation and transportation. When the groundwater table was reached, miners started draining it mechanically (pumps) or by gravity (horizontal adits). The ore, along with the surrounding rock, was transported to the surface, where it was sorted, crushed and washed to produce an ore concentrate, which was then further roasted (to remove contamination) and finally smelted to obtain pure metals such as copper, lead and eventually silver. The extraction method depended on the type of ore and its metal content. In this regard, mining and smelting technology function as a feedback mechanism. It was a technological response to emerging problems, but it also has an ecological dimension, as it demands different fuels, produces toxic substances or accumulates waste. Nonetheless, it facilitates the movement of ore.

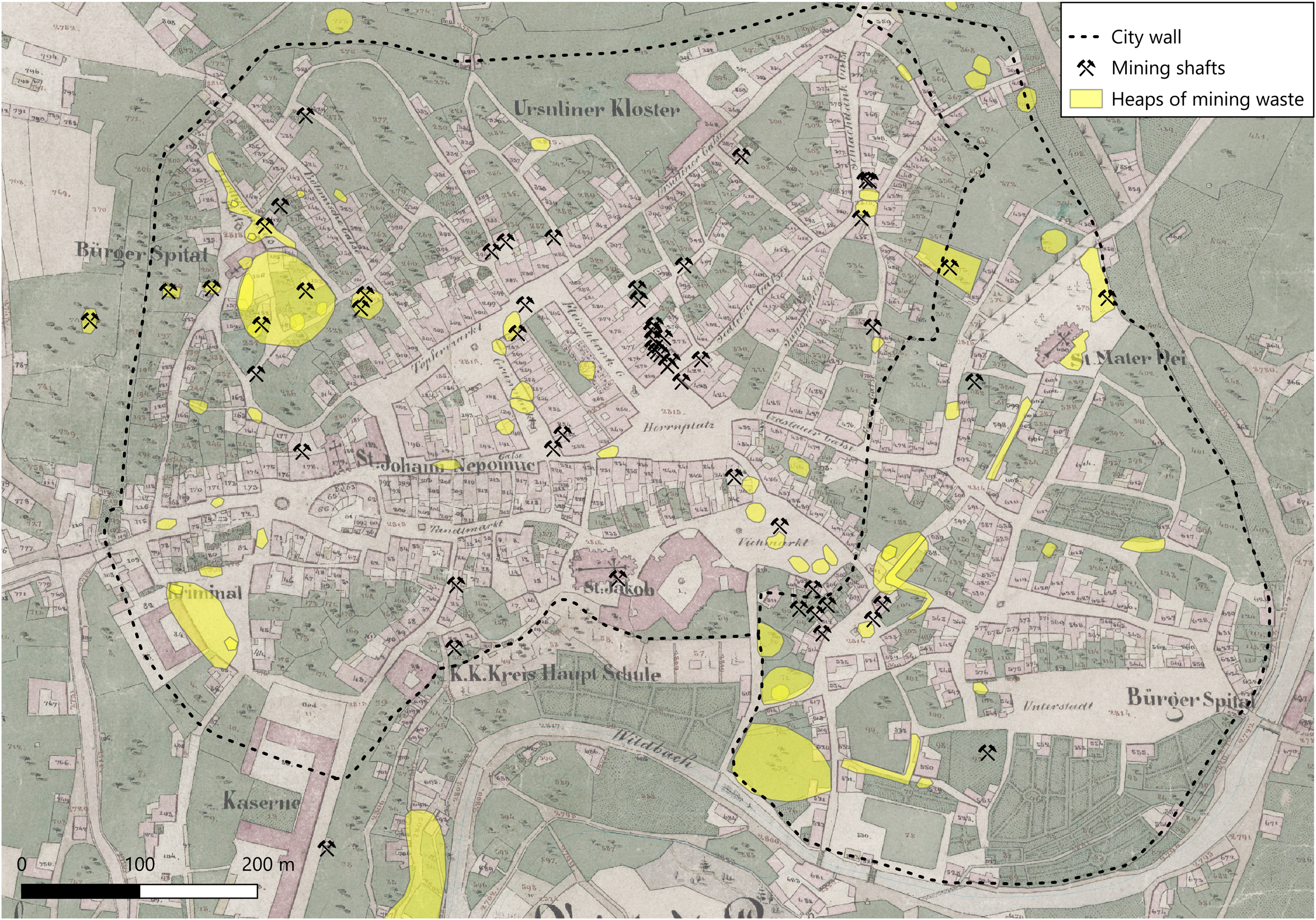

In Kutná Hora, mining probably began on hills in the north, specifically along the Kuklické and Staročeské belts, where ore was closer to the surface (Bartoš Reference Bartoš2004a, 162; Bílek Reference Bílek2000d, 3; Reference Bílek2000e, 13). No later than the beginning of the 14th century, mining expanded to the Grejfské, Oselské and Roveňské belts (Bílek Reference Bílek2000b, 6; Reference Bílek2000c, 4; Reference Bílek2000f, 14). Because a large part of the deposit was beneath layers of clay, the mines quickly deepened. By the early 14th century, some shafts had horse-powered winches, indicating depths of 70–80 metres (Bílek Reference Bílek2000c, 6). By the 15th century, some mines on the Osleské belt reached depths of 500 metres (Bílek Reference Bílek2000f, 14). The effects of underground mining are visible in the town centre, where many houses sit on layers of medieval mining waste (Figure 4). Moreover, the water table was reached swiftly, as the earliest mention of the drainage adit dates to 1305 (Kořan Reference Kořan1950, 7). Unfortunately, there is no direct evidence of processing sites in the town. However, an insight came from the unique depiction of mining activity from the end of the 15th century in Kutná Hora that illustrates all stages of production (Figure 5). The extent of smelting is clear from the amount of slag accumulated west of the town, estimated at 500,000 tonnes (Bílek Reference Bílek2001, 58). It remains unknown whether this is solely a medieval dumping site or also includes early modern waste.

Figure 4. Potential traces of mining in the town centre, background: cadastral plan from 1839 (Originální mapy stabilního katastru 1:2 880, B2_a_4C_3402_6, Archiv of Zeměměřický uřad Praha).

Figure 5. Illustration from end of the 15th century depicting mining and processing of ore in Kutná Hora, by Prague’s illuminator Matouš (Wikipedia, public domain).

This scale and complexity also required legal regulation. That was why the king granted a new mining law, Ius Regale Montanorum, to the mining community in 1300, which became another turning point in the town’s development (Bílek Reference Bílek2000a). The law regulated mines spatially, controlled mining and smelting operations, established a hierarchy of officials and their duties and even protected labourers. This was necessary to ensure a stable flow of silver to the king’s mint and treasury, serving as a political feedback mechanism.

People, capital, political power and the emergence of the town

The discovery of ore initiated a feedback loop in population growth: people moved to work in mines, which led to more ore being mined and attracted even more individuals. Such an inflow of people was typical, as medieval miners were mobile and sought new opportunities across different mining regions (Asrih Reference Asrih and Hemker2020; Hemker and Lobinger Reference Hemker, Lobinger and Hemker2020). The first arrivals were skilled workers, such as miners and smelters, often Germans, as indicated by local place names (Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000, 41). Additionally, there were labourers and service providers, including blacksmiths, rope makers, potters (lamps) and suppliers of food, timber and charcoal. These groups are mentioned in the mining law from 1300.

As mentioned earlier, Kutná Hora’s mining was advanced and large-scale. To sustain it, financial capital was needed to cover wages, tools and fuel. Another feedback loop was in operation: more money, more ore, which generated more money. Since kings were usually impoverished, the capital often came from urban society, from people involved in the metal trade who invested in mining and smelting companies. In Kutná Hora in the 13th century, such investors came from Prague, possibly from Kolín and Čáslav, as well as other mining regions (Borovský Reference Borovský and Jurok2001, 98). They invested in mining to make a profit from it, thereby multiplying their capital. Overall, individuals who owned mining claims (both investors and independent miners), subcontractors, labourers and some artisans formed a mining community (Bartels and Klappauf Reference Bartels, Klappauf, Bartels and Slotta2012, 219). They were subject to mining law, which granted them personal freedom, self-governance and independence from local lords’ authority. These privileges granted by rulers aimed to attract people and capital (Bartels Reference Bartels, Kim and Nagase-Reimer2013, 118).

This introduces the political element: the king’s involvement. Usually, smaller mines were overseen by a local mining centre, but here, the influx of people and capital led to a rapid increase in silver production. This caused the previously mentioned tipping point, resulting in a new law for the community. However, what followed was monetary reform, including the relocation of all mints to Kutná and the start of minting new coins, the Grossi Pragensis (Žemlička Reference Žemlička2014, 369–390). This involved relocating essential central functions to Kutná, such as the mint and the king’s officials responsible for mining across the entire kingdom. These positions were typically held by wealthy individuals involved in mining, which further drew people and capital to new mines.

An interaction between the flow of silver, population, capital and political authority leads to another tipping point: the emergence of the town in a legal sense before 1308 (Bartoš et al. Reference Bartoš, Novák, Posil, Vaněčková, Vaněk, Velímský and Žemlička2010, 6). This process results not only from social factors, but also from spatial processes of population aggregation, demonstrating how the socio-ecosystem developed across the landscape.

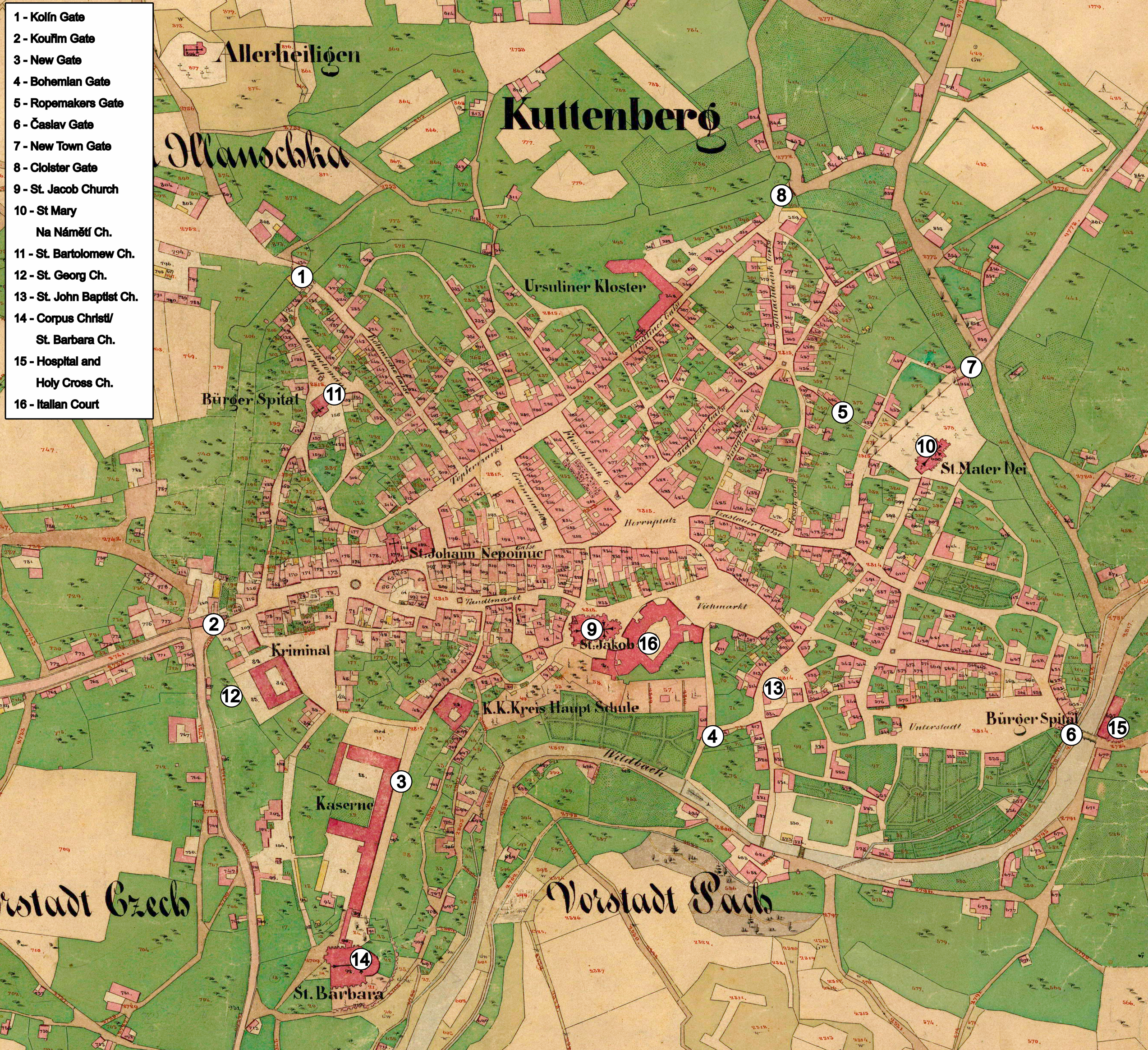

The town probably emerged from multiple mining settlements. Such settlements, consisting of rows of houses situated beside mines, were common in the 13th and 14th centuries (Derner Reference Derner2018; Hrubý, Derner, and Skořepová Reference Hrubý, Derner and Skořepová2019; Hrubý et al. Reference Hrubý, Kmošek, Kočárová, Koštál, Malý, Milo, Tešnohlídek and Unger2021; Schwabenicky Reference Schwabenicky2009). The town developed at the end of the 13th century on a high terrace above the river, amidst the mining fields, likely along the main road dating archaeologically to that period (Frolík and Tomášek Reference Frolík, Tomášek, Buśko, Klápště and Leciejewicz2002). Precisely at the end of the 13th century, the king built his castle, which served as a mint (the so-called Italian Court), directly on the edge of the terrace, outside the mining areas (Záruba Reference Záruba2008). The future urban population began settling nearby. Architectural surveys carried out throughout the 20th century in the town centre revealed that houses dating prior to 1420 lined the old main street.Footnote 1 Another potential focus of early urban development was the churches, which may have evolved from mining chapels. By 1304, the town was already encircled by a fence, soon followed by the city wall (Razím Reference Razím2020, 421) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Kutná Hora cadastral plan from 1839 (Originální mapy stabilního katastru 1:2 880, B2_a_4C_3402_6, Archiv of Zeměměřický uřad Praha).

The gathering of people from various groups, such as merchants, artisans, labourers, clergy and officials, led to the concentration of central functions and social connections. This bottom-up process complemented the king’s top-down approach, which focussed on revenues from mines, regulating the life of a new commune, and securing its privileged status. These two processes are evident in the urban fabric, the connection of growth due to mining, and attempts to create regular city blocks typical of the period.

Accumulation of wealth and political power

From the beginning of the 14th century, Kutná Hora grew as an urban community. Mining investors from the 13th century became patricians and members of the town council. The town gained the status of a royal city and was granted several economic privileges. It became a market centre for both mining and non-mining goods (Bartoš et al. Reference Bartoš, Novák, Posil, Vaněčková, Vaněk, Velímský and Žemlička2010, 7; Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000, 50–52). Additionally, it played a key role in the kingdom’s political scene, thanks to close ties with the king (via mining officials) and the wealth accumulated by Kutná Hora’s burghers, especially the families who were there from the beginning. They held power for most of the 14th century and expanded their investments into real estate and high-ranking positions in other towns (Borovský Reference Borovský and Jurok2001). The material consequence of wealth accumulation were visible within the town. Whilst many houses remained wooden with stone cellars, patrician palaces began to emerge towards the end of the 14th century (Muk Reference Muk1994; Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000, 313–314). Moreover, the town’s prosperity was reflected in numerous churches (Bartoš et al. Reference Bartoš, Novák, Posil, Vaněčková, Vaněk, Velímský and Žemlička2010, 7). Principal amongst them was the first parish church, Corpus Christi and St. Barbara, constructed outside the city walls at the end of the 14th century by the Brotherhood of Corpus Christi formed by local patricians (Bartoš et al. Reference Bartoš, Novák, Posil, Vaněčková, Vaněk, Velímský and Žemlička2010, 8). Its location stemmed from a dispute over parish rights with the Cistercian cloister, and it was built on lands owned by Prague’s bishop, highlighting the complex legal situation faced by the town.

The crises

The sustainability of silver’s flow relies on a feedback loop involving the deposit, population, capital and technology. Changes in these elements inevitably lead to cascading effects throughout the system. The first issue was the exhaustion of rich, easily accessible ores and the need for costly, deeper mining; as a result, production levels in Kutná Hora declined at the end of the 14th century (Holub Reference Holub2018). An indicator of a mining crisis could be the migration of wealthy families into less risky pursuits such as banking, trade and real estate (Musílek Reference Musílek2012, 123). However, what struck Kutná Hora’s mining industry was a sudden lack of capital. Paradoxically, this was a consequence of the town’s political power and the ethnic origins of its inhabitants. When the Hussite wars broke out at the start of the 15th century, the city, inhabited by German-origin patricians, supported the king against the Hussites. This conflict marked another turning point in the town’s history: the destruction of the town and the expulsion of all German patricians (Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000, 60–64). Along with the wealthy class, their capital vanished. This nearly brought mining production to a halt, emphasizing the importance of capital flow to the system’s survival. The Hussites attempted to revive mining, but it took decades, and restoring the banished burghers resulted in increased production levels (Kořan Reference Kořan1950, 9). The town was large enough, and the deposits were sufficiently rich to withstand the crisis and enter a second cycle, underscoring the significance of connections with global flows.

The second cycle

The cycle of feedback between the flow of silver, technology and capital repeated in the second half of the 15th and 16th centuries. It was accelerated by European population growth and demand for metals. Mining production in the town began to increase in the mid-15th century. Thanks to new investments and inventions, such as refining silver from copper production, growth substantially enabled another cycle of wealth accumulation. The city obtained new privileges and again became a crucial political actor. Over the second half of the 15th century, the city was reconstructed in a new late Gothic style, with large patrician palaces and new investments in public spaces (Kořan Reference Kořan1950, 9–10; Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000, 67–71). Because another decline in production was inevitable, especially as the flow of silver from the New World lowered global prices, the town shifted its economic foundations from mining to trade and craft. In 1585, there were 50 different crafts in the city. Additionally, at the end of the 16th century, the town began investing in real estate and fisheries (ponds) (Štroblová and Altová Reference Štroblová and Altová2000, 118–119). Mining nearly disappeared in the 17th century, along with the town’s political stature, but the community persevered and still exists today.

Ecological impact and unforeseen consequences

Thus far, I have focussed on the social elements of the system. However, they were not isolated from the environment. Its feedback was evident at different scales, both geographical (local, regional) and temporal (long-term events). The geological structure of the deposits required miners to adapt technology, find solutions and utilize more resources. Ultimately, it was the deposit that made people wealthy. In underground mines, smaller tipping points occurred more frequently, such as rock collapses or flooding, rendering them inaccessible. On the surface, mining could alter the landscape very quickly. Excavations north of the city centre uncovered 150 traces of shafts and prospecting pits over an area of 300 m by 50–100 m, along with channels and roads, mostly dating to the 13th and 14th centuries, illustrating the complexity of the mining fields (Velímský Reference Velímský2012). Traces of shafts and waste heaps in the city centre show a similar picture (Figure 4). It caused local erosion and the build-up of waste materials. In the long run, these wastes could become problematic. Piles of waste from sorting, crushing, washing and smelting contained large amounts of heavy metals such as lead, copper and cadmium, which remained in the same place for a lengthy period, threatening soil and water contamination. Research on pollution indicates elevated levels all around the town (Horák and Hejcman Reference Horák and Hejcman2016). Additionally, smelting produced significant amounts of toxic fumes that could affect workers’ health and possibly nearby residents.

Pollution and erosion were usually confined to mining and smelting sites, but the greatest impact stemmed from deforestation. Mining and smelting required wood for constructing infrastructure, timbering mines and especially for smelting (Straßburger and Tegel Reference Straßburger and Tegel2009). The demand depended on production scale, ore composition and technology. Therefore, mining relied on local supplies, which were reduced by the high costs of transportation and other medieval communities that depended on forests (Wilsdorf Reference Wilsdorf1960, 36). A solution was political feedback: miners had privileges that guaranteed them cheap access to forests (Majer Reference Majer and Westermann1997, 223). Subsequently, forests were cut for timber or burned for charcoal. There are a few insights into charcoal production in the Kutná Hora region. A document from 1327, issued by King John of Luxembourg, granted charcoal producers special privileges, including the right to pay for forest areas after selling charcoal, tax exemptions on roads to the town and the right to use the shortest routes to Kutná Hora. By the mid-14th century, charcoal was transported from as far as 30 km north of Kutná Hora (Husa Reference Husa1957, 12). As we can see, given the scale and clear importance of the issue to authorities, there was no indication of a supply crisis in the Middle Ages. Timber supplies became a major problem during the 16th century. Local stocks were depleted, and the king had to order lords from nearby lands to provide access to forests for charcoal burners. Unfortunately, due to previous crises, there were not enough people to produce and supply fuel. The solution was importing wood from the north via the Elbe River (Kořan Reference Kořan1950, 19). Another technological innovation was introduced to reduce transport costs, and the channel was built directly near a town to facilitate timber transport (Bartoš Reference Bartoš2004b).

Conclusions

This paper presents an ecological framework for understanding mining towns as a complex interaction between society and environment, driven by flows of resources, people and information. By tracking tipping points, flows and feedback through historical sources, it goes beyond traditional economic or institutional explanations to uncover the dynamics of mining communities. Special attention was put on the role of social hierarchies in the mining town ecosystem.

The case of Kutná Hora demonstrates how mining towns functioned as adaptive systems sustained by the constant circulation of matter, energy, people and capital. The discovery of ores triggered a series of flows and positive feedback loops connecting local geology with European and then global networks. The deposit, its structure and composition prompted people to settle and apply appropriate technology to extract it. However, population growth and production depended on financial resources for labour, raw materials and fuel. The next level involves a political ecology of this system: mining was embedded in social hierarchies, indicating who owned the land and who held the rights to mine. The king was responsible for guaranteeing privileges, law enforcement and crucially, access to cheap energy. Nonetheless, each of these elements influenced the others. The king required miners and investors to carry out the work, and they needed the king to ensure a secure profit. Consequently, social interactions occurred swiftly and were intertwined with the environment via flows of matter. However, this flow operated on a different timescale. It took generations to reach the critical limits of deposits and forest productivity. This also highlights an additional aspect revealed by these interactions: profits were transferred to the state and the wealthy, whilst ecological burdens were borne locally by those working in the mines.

The presented model is based on assumptions and correlations amongst events, and as such, does not establish causation. Still, it opens a new perspective through identifying the quantifiable elements within the system that can be traced in written, archaeological and environmental records. It points towards the analysis of metabolic flows such as timber, charcoal and other mass commodities to show, on the one hand, the scale of environmental impact, and on the other, the economic potential of the community. Levels of environmental impacts can be further investigated by examining scale, intensity, chronology and quantity, such as the area cut for forests, contamination levels and erosion. The next step is to move from theoretical consideration to computational modelling.

The presented model also uncovers additional gaps in our understanding of pre-modern mining towns. The impact of the altered environment on the population’s quality of life remains scarcely studied. This gap is primarily due to a lack of bioarchaeological data on mining communities, but it could be partly addressed through analysing aspects of daily life such as housing, diet and material wealth. Another significant gap involves the integration of cultural constraints, values, beliefs and ideologies that influence behaviour in mining regions. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, perceptions of nature underwent a notable shift. This change was partly linked to the rise of extractive capitalism, which also had origins in mining. It raises important questions about how these changes were connected to mining and its interaction with the environment, and how different social agents, such as miners, officials and investors, perceived minerals and their extraction, and how this influenced the entire system.

Adopting an ecological framework for studies of medieval mining towns (and all other towns) encourages further development of interdisciplinary research by shifting it from merely correlating different types of sources to identifying proxies for ecological change. It transitions from basic technical questions about what things looked like to explaining why various ecological and social patterns occurred and what their deeper roles are in today’s ecological challenges.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Joanna Sudyka, Tomasz Związek, Ulrich Müller, Michael Kempf and René Ohlrau, as well as the Journal’s editorial team and reviewers, for their insightful and helpful comments.

Funding statement

Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy - EXC 2150 – 390870439.

Competing interests

The author declares none.