Introduction

Online public consultations (OPCs) are frequently used by governments to invite citizens and organisations to participate in the formulation of public policies. They constitute a form of stakeholder engagement aimed at information‐gathering and reducing the levels of bias and inequality in interest representation in policymaking by increasing the levels of participation and the diversity of interests informing decision‐making (Balla & Daniels, Reference Balla and Daniels2007). OPCs are widely used in the US regulatory policymaking under the ‘notice and comment’ procedure (Balla, Reference Balla2015; Yackee, Reference Yackee2019), constitute a landmark of EU supranational policymaking and are also employed in national and sub‐national policymaking in countries across Europe (OECD, 2022).

For bureaucracies, OPCs constitute a key mechanism to bring the public in and democratise a realm of policymaking traditionally characterised by expert‐informed, technocratic decision‐making. The extent to which OPCs managed to achieve this and inject pluralism in policymaking constitutes a key question highlighted in the research on participatory governance (Balla & Daniels, Reference Balla and Daniels2007; Rasmussen & Carroll, Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014; Røed & Wøien Hansen, Reference Røed and Wøien Hansen2018). While recognising the important role of OPCs as venues of interest representation, this literature debates the extent to which OPCs manage to increase the participation of actors that were traditionally under‐represented (citizens and public interest organisations) and enhance the plurality of interests voiced. Particularly relevant are the institutional aspects of consultation design and their impact on participation (Beyers & Arras, Reference Beyers and Arras2020; Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2015; Pagliari & Young, Reference Pagliari and Young2016). However, their role is less frequently examined as part of systematic large‐n analyses. Existing research has examined extensively the role of stakeholder‐level characteristics (Quittkat, Reference Quittkat2011; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2015) and of the policy environment (Nørbech, Reference Nørbech2024; Rasmussen & Carroll, Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014; Røed & Wøien Hansen, Reference Røed and Wøien Hansen2018; Van Ballaert, Reference Van Ballaert2017) in explaining levels and diversity of participation in OPCs.

We address this gap and focus on a key aspect of consultation design: the formal invitations policymakers extend to stakeholders inviting them to participate in consultations. In relation to them, we ask: Does the number of government invitations to consultations increase the levels and diversity of stakeholder participation in OPCs? While these invitations represent a key institutional opportunity structure for stakeholders to get informed about, and participate in and shape policymaking, they remain largely unexamined in the literature (notable exceptions are Lundberg, Reference Lundberg2013, Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2015). We build an argument explaining why the number of invitations should be systematically and positively associated with higher levels of participation and diversity of interests and how this pattern is conditional upon the type of policy act on which the government consults. We test our argument on a new dataset containing information about stakeholder participation in 4062 OPCs organised by the Norwegian government across all policy areas during 2009–2023. We find that the number of invitations is systematically associated with higher stakeholder participation, higher diversity of interests represented and a higher likelihood of and more frequent citizen participation. The association between invitations and participation level is moderated by policy act type: the interaction term indicates statistically significant differences in participation levels between legislative acts and government regulations and EU directives, yet not between legislative acts and government reports. The association between invitations and increased diversity varies systematically with policy act type: it is significantly higher on legislative acts relative to all non‐legislative acts. The overall direct impact of invitations, as well as the effect conditional on policy act type, is modest in size relative to the size of the direct effects of policy act type and policy area type on the level and diversity of participation.

Our focus on OPCs is justified by their extensive and frequent use in contemporary governance (OECD, 2022). They are credited with the opportunity to democratise bureaucratic policymaking by enhancing the levels of public participation, the diversity of interests represented, and the presence of actors previously underrepresented or absent from the bureaucratic realm, namely citizens and organisations that are not policy insiders nor prominent organisations. However, the extent to which OPCs managed to generate higher and more diverse participation, especially on behalf of citizens, is a relevant question addressed in relation to US federal policymaking (Balla & Daniels, Reference Balla and Daniels2007; Coglianese, Reference Coglianese2004) and EU supranational policymaking (Bunea & Lipcean, Reference Bunea and Lipcean2024; Nørbech, Reference Nørbech2024), which remains a pertinent puzzle regarding consultations organised by national governments. The question is particularly relevant for countries that witnessed a strong corporatist tradition of interest representation such as Norway, our empirical testing ground. Like the other Scandinavian countries, Norway had a long tradition of corporatism, which, however, started to decline in the past two decades when a shift to more pluralist and lobbyism‐like forms of interest representation emerged (Rommetvedt, Reference Rommetvedt and Knutsen2019). Considering this, the extent to which policymakers’ efforts to invite and mobilise more and more diverse stakeholders to participate in OPCs are successful, provides important information about the extent to which institutions can shape and encourage the creation of a pluralistic system of interest representation in the bureaucratic arena through online participation when this is set against a corporatist tradition. In this respect, Norway provides an ideal hard case to test our argument: if government invitations manage to systematically increase the density and plurality of interests represented in the context of a polity with a strong corporatist past, then their contribution to increasing participation and diversity in countries with more pluralist or neo‐pluralist systems of interest representation could be stronger. Furthermore, like its Scandinavian neighbours, Norway provides public information about both government invitations and stakeholder participation. While information about who participates in OPCs is usually published online in most polities, the public provision of systematic information about policymakers’ invitations and outreach efforts is less common (Blanc & Ottimofiore, Reference Blanc, Ottimofiore, Dunlop and Radaelli2016). The Norwegian case illustrates the importance of government transparency and systematic public information provision for research on participatory governance and highlights an important obstacle in the knowledge accumulation in this area of research: the absence of structured, transparent, easily accessible public records documenting policymakers’ outreach efforts aimed at encouraging stakeholder engagement in policymaking. Lastly, different from Sweden and Denmark, Norway constitutes a country that is neglected in the research on participatory governance and stakeholder participation in bureaucratic policymaking and features less frequently in the literature on lobbying and interest groups (Allern, Reference Allern2012).

Examining the link between government invitations and key dimensions of participation is relevant for several reasons. First, it allows assessing the extent to which institutional measures aimed at ‘making policymaking public’ (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2014) and at generating and encouraging public participation work and increase; the plurality of interests represented, preventing bias. Second, since invitations are usually sent to institutional or organisational actors, analysing this link provides relevant insights about the conditions under which these invitations may also encourage citizen participation. This enhances our understanding of how organisations may act not only as a ‘transmission belt’ between policymakers and citizens but also as an ‘activation belt’ of citizen participation in an arena of elite‐driven, expert‐informed decision‐making. Third, analysing the impact of invitations on the frequency and diversity of participation allows capturing two dimensions of stakeholder engagement in policymaking that are related but ‘not wholly commensurate’ (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2015, 489). Research showed that high participation does not necessarily result in high diversity, and the relationship between frequency and diversity must be inquired empirically (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2015). If invitations generate high participation on behalf of organisations representing only one or two types of (functional) interests, then observed stakeholder diversity is low. Furthermore, invitations may have a negative impact on participation and diversity due to what the policy practice and research have identified as ‘consultation fatigue’. Since OPCs are frequently organised by bureaucracies across policy areas, and sometimes across levels of government, stakeholders receive several invitations to consultations that may happen simultaneously or within a short time span. This puts strain on the attention and resources of stakeholders who find it difficult to participate in several consultations on different policy topics at the same time (Strømsnes et al., Reference Strømsnes, Ervik and Reymert2023, 51).

We contribute to the participatory governance and bureaucratic policymaking research in several ways. Theoretically, we conceptualise government invitations as a feature of consultation design that aims to increase the publicity of the government's initiatives while enhancing the informational advantage and procedural legitimacy of governmental policymaking. Our argument also recognises the importance of policy act characteristics as an epitome of the political and inter‐institutional context against which OPCs take place. Empirically, we examine a polity that was previously under‐researched in the literature on participatory governance (Norway) and test our argument on a new dataset containing information about 104,460 instances of citizen and 146,693 instances of organisational participation in 4062 OPCs across all policy areas during a 14‐year period.

Government invitations and stakeholder participation in online public consultations

The research on stakeholder participation in public consultations identifies three categories of factors shaping the levels and diversity of stakeholder engagement. The first set of studies highlights the importance of stakeholder‐level characteristics such as organisational form, resources, representative mandate, embeddedness in policy and lobbying networks, and the type of (functional) interest represented for explaining the frequency and form of participation (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2014; Coglianese, Reference Coglianese2006; Golden, Reference Golden1998; Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Schmid, Yackee and Zhan2009; Yackee & Yackee, Reference Yackee and Yackee2006; Yackee, Reference Yackee2015). A second set emphasises the importance of policy context and especially of policy area and policy issue characteristics such as the level of issue public salience and level of policy complexity (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2015; Kerwin & Furlong, Reference Kerwin and Furlong2018; Pagliari & Young, Reference Pagliari and Young2016; Rasmussen & Carroll, Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014; Røed & Wøien Hansen, Reference Røed and Wøien Hansen2018; Van Ballaert, Reference Van Ballaert2017). A third set underlines the importance of institutional factors such as consultation format (Beyers & Arras, Reference Beyers and Arras2020; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Blom‐Hansen and Senninger2021; Fraussen et al., Reference Fraussen, Albareda and Braun2020) and features of procedural rules and administrative acts (Balla, Reference Balla1998, Reference Balla2015; Potter, Reference Potter2019; West, Reference West2004).

We build on this institutional perspective and notice the conspicuous absence of studies focusing on a conceptually intuitive institutional factor and consultation design feature that plays an important role in generating and encouraging participation: the (number of) invitations to consultations sent by policymakers to relevant institutional and organisational actors. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies explicitly or implicitly have examined this. Lundberg (Reference Lundberg2013) investigated the impact of the government selection process in the Swedish remiss (public consultation) procedure on levels of pluralism by looking at which categories of organisations participate in consultations. It examined how organisational characteristics, such as insider status and organisational resources shape participation. Rasmussen (Reference Rasmussen2015) analysed who participates in public consultations in Denmark and the United Kingdom by looking at how interest group type and ‘system‐specific differences’ (corporatism vs. pluralism) shape participation. This study examines the impact of invitations as part of a sub‐set of analyses examining the propensity of different organisations to answer the Danish government's invitations. Both studies show that, in Sweden and Denmark, stakeholder‐level characteristics matter in how they respond to invitations: policy insiders and traditional corporatist actors (trade unions, employers’ associations, etc.) respond and participate more frequently.

While in the Scandinavian countries, this invitation procedure has its roots in the traditional corporatist arrangements of interest representation (Lundberg, Reference Lundberg2013), it is also a practice used in pluralist systems such as, for example, the United Kingdom (LSE GV314 Group 2012). Most invitations are sent to institutions and organisations that are relevant stakeholders in the context of the issue or initiative submitted for consultation. We argue that these formal invitations are a key feature of consultation design that shapes the patterns of participation through an informational logic and a procedural logic that underpins policymakers’ incentives to invite and stakeholders’ incentives to participate.

From an informational perspective, government invitations are a relevant public signalling device. First, for policymakers, invitations represent an easy‐to‐use formal channel through which they disseminate information to relevant stakeholders about the start of a policy initiative. Invitations help publicise the initiative and raise public awareness. From this perspective, the number of invitations indicates the breadth of socio‐economic impact and policy scope of an initiative, based on the assumption that a higher number of invitations corresponds to a broader pool of relevant stakeholders. Second, invitations signal to stakeholders that they are recognised as relevant policy actors and affected interests. Policymakers invite them to have a voice and get formal access to the decision‐making process. This constitutes a first yet critical step towards informing and shaping the policymaking process and outcomes, serving thus as a relevant incentive for stakeholders to participate. Stakeholders also have incentives to participate in consultations to which they were invited to preserve the status of recognised relevant interests/actors. Third, invitations can have an informational multiplication effect: stakeholders receiving invitations may disseminate them to others whom policymakers did not think of or could not reach directly. For example, business associations may forward invitations to their member firms encouraging their individual participation to strengthen the numerical presence and voice of their interests in the consultation. Similarly, organisations representing individuals (e.g., consumer organisations, trade unions, NGOs) may share the government's invitation with its members to encourage their direct (individual) participation. Organisations may also launch public information campaigns through social or traditional media to promote consultation awareness and citizen participation. Such organisational efforts may even result in coordinated campaigns and submissions documented in the research on US federal rulemaking (Balla et al., Reference Balla, Beck, Meehan and Prasad2022). Thus, invitations to consultations can raise awareness amongst both obvious and non‐obvious stakeholders and even mobilise the direct participation of a traditionally underrepresented category of stakeholders engaged in bureaucratic policymaking and public consultations: citizens.

From a procedural perspective, government invitations are a unique opportunity for policymakers to design a consultation process that is open to and inclusive of a diversity of interests, being thus less susceptible to the perils of bias and unequal representation. Policymakers can create an institutional opportunity to address structural inequalities in participation and representation by disseminating information about the initiative amongst stakeholders that were underrepresented in bureaucratic policymaking, in general, or in the case of a specific policy area or initiative. This can be the case for stakeholders encountering more severe mobilisation for action and collective action problems, such as consumer or environmental groups or stakeholders that possess fewer resources and struggle to get informed about consultations and initiatives. As such, invitations constitute an instrument of consultation design that can significantly improve the procedural legitimacy of the consultation process and increase the levels of stakeholder trust in it. This elevated trust encourages stakeholders to participate in consultations to express their views and inform the policy process. Additionally, knowing that policymakers are committed to consulting a plurality of interests further incentivises stakeholders to participate because they expect (and partially fear) that stakeholders with opposing policy views to their own might also engage in consultations. Participation becomes a necessary (albeit not sufficient) condition for countervailing ‘policy foes’ and stakeholders with opposing views and interests.

Following from this, our baseline expectation is that:

1.1H The higher the number of government invitations to consultations, the higher the number of stakeholders participating in OPCs.

1.2H The higher the number of government invitations to consultations, the higher the diversity of stakeholders participating in OPCs.

The moderating effect of policy act type

Policymakers have full discretion over the decision to send invitations to consultations, how many invitations to extend, and to whom these are addressed. The literature on participatory bureaucracies highlights that the decision about ‘how to bring the public into bureaucratic policymaking’ is informed by strategic considerations regarding bureaucratic legitimacy, autonomy, and power within the broader institutional context (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2014; Potter, Reference Potter2019). For example, Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2014, 31) shows that ‘the conditions […] of public participation’ in bureaucratic decision‐making are likely to depend on bureaucrats’ level of information required to perform a task and the level of independence they have over task implementation. As such, ‘bureaucrats are less likely to seek public participation for tasks when agency enjoys high information and independent authority’ (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2014, 36), and they are ‘more likely to seek public participation for high information tasks in conditions of task interdependence than in conditions of task independence’ (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2014, 46). Similarly, Potter (Reference Potter2019, 114–128) argues that consultations can be strategically used by deciding the time length of the consultation period. Bureaucracies ‘expand the opportunities for public participation’ when they ‘expect that interest groups will support their cause in front of their political principals’ (Potter, Reference Potter2019, 115). Conversely, ‘when political principals are not aligned with the bureaucratic agents and when relevant interest groups are predisposed against an agency, the agency will work to limit participation’ (Potter, Reference Potter2019, 116). Both highlight the relevance of the relationship between bureaucracies and their political masters (legislators) in the former's decisions about public consultation design.

We recognise this strategic nature of public consultation design, and we expect it to inform policymakers’ decisions about how many invitations to send. We argue that this decision is informed by considerations related to policymakers’ informational and procedural legitimacy needs regarding the policy act on which they consult. Policymakers have incentives to send a high number of invitations when either their informational needs are high, their need for procedural legitimacy is high, or they face a high need for both. Broadly speaking, informational needs are higher on more complex policy acts, while process legitimacy needs are higher when policy acts tackle issues that are publicly and/or politically salient or controversial. Policymakers have incentives to extend the highest number of invitations when policy acts are both complex and politically salient, and second highest when policy acts are either complex or politically salient. Policy act characteristics also shape stakeholders’ incentives to participate in consultations (Kerwin & Furlong, Reference Kerwin and Furlong2018; Røed & Wøien Hansen, Reference Røed and Wøien Hansen2018). The scope, complexity and salience of policy acts shape participation by creating different cost‐benefit constellations that encourage or dissuade stakeholders’ engagement. Therefore, we argue that policy act characteristics play a moderating role in how invitations shape participation insofar as they inform both policymakers’ decisions about how many invitations to send and stakeholders’ incentives to participate.

Complex policy acts increase informational needs and make policymakers more dependable on their external environment to access relevant information and maintain their informational advantage over their political masters. Finding suitable and feasible solutions for issues contained in complex policy acts requires access to more diverse sources of information, which are more likely to emerge in the context of consultations that generate high and diverse participation. This incentivises policymakers to send out more invitations, hoping that this will increase the diversity, if not also the quality of the information received.

From stakeholders’ perspective, engaging meaningfully with complex policy acts constitutes a non‐negligible challenge, especially for categories of stakeholders who struggle to access and manage the expert and oftentimes technical information required by these acts, such as citizens or organisations that do not possess the specialised knowledge nor have the necessary organisational resources to secure it (Rose‐Ackerman, Reference Rose‐Ackerman2021). Despite policymakers’ efforts to invite many stakeholders to consultations on complex policy acts, stakeholders’ participation and diversity are low because the informational demands imposed on them are high (Røed & Wøien Hansen, Reference Røed and Wøien Hansen2018). Since on these acts, policymakers’ propensity to invite more stakeholders is oftentimes met by stakeholders’ difficulties in participating, we expect that together, these two dynamics cancel the moderation effect of policy act complexity on the relationship between invitations and participation.

The situation is different regarding policy acts that are politically salient. These require and incentivise bureaucracies to generate procedural legitimacy as well as broad societal and political support for their initiatives. For them, policymakers’ invitations are equally motivated by informational and legitimacy needs. Securing procedural legitimacy and public support strengthens the government's claim that its acts were informed and supported by a broad range of stakeholders and interests. This is hoped to strengthen their power to pass initiatives into law following legislative debate and voting, with few or no amendments. On politically salient acts, policymakers’ incentives to consult wide are met by stakeholders’ interests to participate in consultations on acts that matter (Røed & Wøien Hansen, Reference Røed and Wøien Hansen2018). Therefore, on politically salient policy acts, we expect to see that the association between invitations and participation is moderated by whether the policy act is politically salient or not.

While the types of acts that governments generate and submit for public consultation differ from polity to polity (OECD, 2022), almost all parliamentary and semi‐presidential systems of government have legislative proposals that are drafted by the government and then debated and adopted by the parliament at the core of their executive policymaking (Rose‐Ackerman, Reference Rose‐Ackerman2021). We consider this type of act to be the most politically salient relative to all other policy acts for both bureaucrats and stakeholders. Policymakers have strong incentives to strengthen their informational advantage and legitimacy because these acts require legislative approval and run the risk of significant legislative amendment and even rejection. These features encourage stakeholders’ participation and voice because they expect that their policy positions are considered both before and after the start of the legislative debate, which in turn increases the probability of them influencing the decision‐making. Stakeholders have stronger incentives to participate in consultations on policy acts that are subject to legislative scrutiny and adoption because consultations offer an additional (pre‐legislative) lobbying venue and opportunity to shape legislative outcomes. Furthermore, they have incentives to contribute to consultations on policy acts that are most likely to have the force of law if adopted. Thus, the association between government invitations and stakeholder participation is likely to be moderated by the policy act type on which the government consults and, specifically, by its property of being a legislative proposal. We therefore expect that:

2.1H The positive association between a higher number of government invitations and increased stakeholder participation is stronger for legislative proposals relative to all other acts.

2.2H The positive association between a higher number of government invitations and increased stakeholder diversity is stronger for legislative proposals relative to all other acts.

Alternative explanations

An important approach in the research on stakeholder participation in public consultations highlights the role of policy context, and especially of policy area characteristics in shaping participation (Rasmussen & Carroll, Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Blom‐Hansen and Senninger2021). The argument is that consultations focusing on (re)distributive issues (e.g., social issues) generate higher participation from more diverse stakeholders relative to regulatory policies, which in turn generate higher and more diverse participation than consultations dealing with foreign policy issues. Therefore, our analyses control for the type of policy area to which a consultation belongs.

Research design

We test our argument on a new dataset containing information about OPCs organised by all ministries of the Norwegian government between 2009 and 2023.Footnote 1 Information about the acts submitted for consultation and stakeholders’ submissions was available on the Norwegian government website under the heading ‘Consultations’ (Høyringar). We identified the full list of OPCs based on the government's consultations dataset posted under the section ‘Overview of consultations’ (Oversyn over høyringssaker). We identified a total of 4062 consultations. Second, we collected information about consultation documents, government invitations and stakeholders. In total, 255 consultations (6.28 per cent) received zero submissions: no stakeholders participated. For the remaining 3807 (93.72 per cent) consultations, we gathered information about the type of (functional) interest stakeholders represented. We identified in total 251,153 instances of stakeholder participation (submissions). Many stakeholders participated in several consultations, so the number of unique stakeholders is lower than that of submissions.

Dependent variables

To examine the link between invitations and patterns of participation, we use two measures: the level and the diversity of participation. These two dimensions are fundamental for assessing levels of pluralism, or conversely of bias, in participation (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2015).

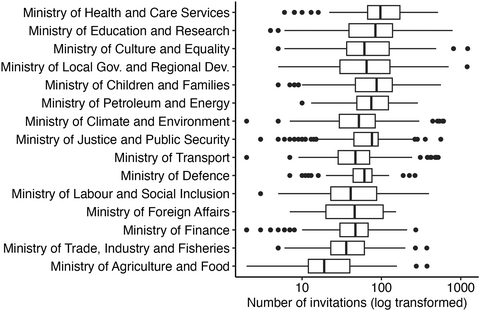

We measure the level of participation using the total (count) number of submissions received on a consultation. This varies greatly across consultations: from 0 to 22,106 (mean 61.83, median 24, SD 460.5). Figure 1 presents the proportion of citizen and organised stakeholder submissions across ministries. Submissions from organisations dominate in relative terms across ministries, but we note a high proportion of citizens’ submissions in consultations organised by the Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Both tackle issues that are fundamental to Norwegian politics and the welfare state: social protection and oil production and management.

Figure 1. Relative participation of citizens and organisations in Norwegian consultations by number of submissions.

Second, we measure the diversity of stakeholder participation at the consultation level by building on recent research on stakeholder participation in public policymaking (Bunea & Lipcean, Reference Bunea and Lipcean2024), by looking at the diversity of interests represented by stakeholders participating in OPCs. We compute a stakeholder diversity index based on the following equation:

Here, ![]() represents the number of submissions contributed by the ith category of stakeholders, while n constitutes the total number of submissions sent on each consultation. Twelve categories are included in the set of stakeholder types i. We create the index in two steps. First, we categorised stakeholders based on the type of functional interests they represent. This information was identified based on each OPC website. We identified the following categories: employer's organisation (Arbeidsgiverorganisasjon); trade union (Arbeidstakerorganisasjon); consumer‐ and interest organisation (Bruker‐ og interesseorganisasjon); ministries; research and education institutions (Forsknings‐ og utdanningsinstitusjon); municipal/regional authorities (includes municipality [Kommune]; county [Fylkeskommune] and county governor [Statsforvalter]); business (Privat virksomhet); citizen (Privatperson); political party (Politisk parti); other voluntary organisation (Annen frivillig organisasjon); other public authority (Annen offentlig etat); other (Annen). Section 1 and Table A1 of the Online Appendix detail our coding.

represents the number of submissions contributed by the ith category of stakeholders, while n constitutes the total number of submissions sent on each consultation. Twelve categories are included in the set of stakeholder types i. We create the index in two steps. First, we categorised stakeholders based on the type of functional interests they represent. This information was identified based on each OPC website. We identified the following categories: employer's organisation (Arbeidsgiverorganisasjon); trade union (Arbeidstakerorganisasjon); consumer‐ and interest organisation (Bruker‐ og interesseorganisasjon); ministries; research and education institutions (Forsknings‐ og utdanningsinstitusjon); municipal/regional authorities (includes municipality [Kommune]; county [Fylkeskommune] and county governor [Statsforvalter]); business (Privat virksomhet); citizen (Privatperson); political party (Politisk parti); other voluntary organisation (Annen frivillig organisasjon); other public authority (Annen offentlig etat); other (Annen). Section 1 and Table A1 of the Online Appendix detail our coding.

Second, we computed the diversity index for consultations receiving at least five submissions so that the index makes empirical sense (3606 consultations). Our diversity measure ranges from 1 to 9.01, with higher values indicating higher diversity (average 4.21, median 4.16, SD 1.43).

Our diversity measure draws on party politics research where it is used to measure the effective number of parties (Laakso & Taagepera, Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979). Our measure weights the number of represented interests based on the share of submissions from each stakeholder category. It captures how many stakeholder types are represented in each consultation with an equal share of comments. It resembles the Herfindhal–Hirschmann Index (HHI) used in the research examining bias (concentration) in interest groups’ participation in consultations (e.g., Beyers & Arras, Reference Beyers and Arras2020) as an alternative measure of actor diversity. Since our analytical focus is on capturing the diversity of interests represented, we consider our measure more suitable for our analytical goal. It captures the effective number of (functional) interests represented in OPCs. Our measure is in an inverse relationship with the HHI: higher values of our index indicate higher diversity of interests represented, while higher HHI values indicate more concentration and thus less diversity of actors. As a robustness test for our models examining the relationship between invitations and diversity, we present in the Online Appendix model specifications using HHI as an alternative measure of stakeholder diversity (Table A2). We find no changes to our results.

To illustrate our diversity index, we briefly discuss consultations with the highest, lowest and median diversity scores. The highest score (9.01) characterised the consultation on residency rules for foreign education workers in Norway, organised by the Ministry of Education and Research. This was relevant for several different stakeholder categories, and therefore the consultation got responses from a variety of stakeholders: private businesses (five responses; 9.65 per cent), citizens (one; 1.9 per cent), consumer groups (four; 7.7 per cent), employer organisations (four; 7.7 per cent), ministries (six; 11.5 per cent), municipal/regional government (six; 11.5 per cent), other public authorities (six; 11.5 per cent), other voluntary organisations (three; 5.7 per cent), research and educational institutions (10; 19.2 per cent), trade unions (three; 5.7 per cent) and ‘other’ stakeholders (four; 7.7 per cent). Four consultations scored lowest on diversity (1), with participation limited to a single stakeholder category: three involved only universities discussing academic legislation (11, 9, and 8 submissions), while the fourth got eight responses only from municipalities regarding an electronic voter marking system for the 2015 local elections. Somewhere in the middle (diversity score 4), we find a consultation organised by the Ministry of Finance on an initiative to change the bookkeeping regulations by specifically removing the option to use work schedules as an alternative to personnel lists. This mobilised consumer groups (three; 15 per cent), trade unions (one; 5 per cent), employers’ organisations (two; 10 per cent), other voluntary organisations (one; 5 per cent), ministries (six; 30 per cent), and other public authorities (seven; 35 per cent). Although the consultation was attended by a fairly diverse set of stakeholder categories, the last two categories were relatively more prominent numerically, which reduced the diversity score.

Explanatory variables

Government invitations

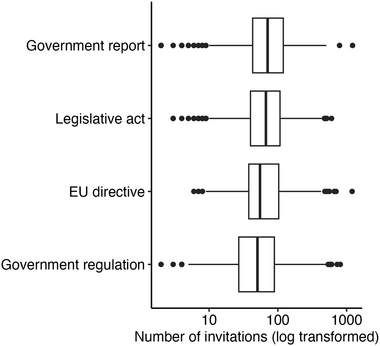

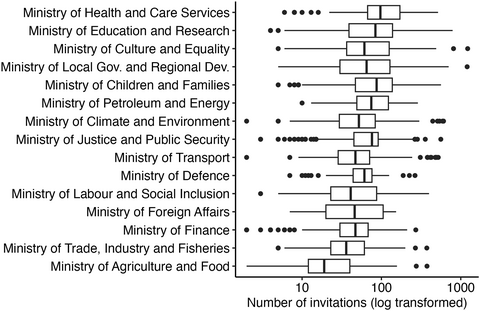

We coded the number of government invitations sent for each consultation based on information from the Norwegian ministries’ websites under the heading ‘Invitations’ (Høringsinstans). For 110 consultations, this information was not available. We cannot determine whether the government did not send an invitation or whether it did not post information about it online. However, as the norm and policy practice are to post this information online, we assume that for these consultations, policymakers sent no invitations and coded these as observations with zero invitations. We identified 325,332 stakeholder invitations sent by the government in relation to 3952 consultations. Our explanatory variable ranges from 0 to 1221 (mean 80.9, median 57.5, SD 84.4). Figure 2 illustrates the variation in the number of invitations across ministries and indicates that the Ministry of Health and Care Services sent out the highest median number of invitations, while the Ministry of Agriculture and Food the lowest.

Figure 2. Distribution of the number of invitations across ministries.

Regarding the content of invitations, we note that all stakeholders receive the same invitation text to one consultation, irrespective of their category. There is variation across consultations regarding the substantive content and text length, as illustrated in Table A3 in the Online Appendix, which exemplifies two invitations. The first was issued by the Ministry of Culture and invited participation in a consultation on ‘Domain Name System‐Blocking of websites that offer gambling that is not authorised in Norway’. The Ministry sent 388 invitations and received 53 submissions from organisations and 185 from citizens. The second was sent by the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation and invited participation in a consultation on the implementation of the EU Directive on the accessibility of websites and mobile applications. The Ministry sent 1203 invitations, but only 47 organisations participated.

Policy act type

Our argument posits that policy act type moderates the impact of invitations on participation. We identified four policy act types:

Legislative acts (Lov): referring to proposals for new (or changes in existing) legislation, which, following consultation, are sent to the parliament for debate and adoption (1222).

Government reports (Norsk offentlig utredning/Rapport): written by a committee or working group, they discuss the knowledge base and potential measures to address different societal problems (Holst, Reference Holst2019) (616).

Government regulations (Forskrift): supplementary provisions to laws which do not require parliamentary approval (1935).

EU directives: The EU acts with significant consequences for Norway, requiring national legislation to implement their policy objectives (289).

Although our conditional hypotheses refer to systematic differences between legislative and non‐legislative acts, our empirics use all act categories to provide a more fine‐grained analysis.

Controls

To assess the role of the policy area in shaping participation, we coded information about the policy area type to which a consultation belonged. Consultations organised by the Ministry of Children and Families, Ministry of Culture and Equality, Ministry of Education and Research, Ministry of Health and Care Services, Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion and Ministry of Local Governments and Regional Development were coded as covering the social policy domain (2346). Consultations organised by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, and the Ministry of Transport were coded as consultations in the economic policy (1477). Consultations organised by the Ministry of Climate and Energy were coded as belonging to the environmental policy (159), while those organised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Defence were coded as belonging to the external policy (80).

We include a time trend variable, which increases from 1 to 15 for each year in the dataset. This accounts for two aspects: the possibility that, over time, stakeholders became more familiar with consultations, which may impact participation, and the increase in the number of organisations in Norway over time (Allern et al., Reference Allern, Arnesen, Hansen and Røed2023) and a shift from corporatism towards pluralism (Rommetvedt, Reference Rommetvedt and Knutsen2019).

Lastly, we control for the length of time the consultation was opened: this ranges from 1 to 242 days. For 33 consultations, the ministries wrongly indicated a closing date that was earlier than the start date. We code this as missing values.

Analyses

We present our empirical analyses in the following order. First, we briefly describe our explanatory variable (number of invitations) and examine its variation across policy acts. Second, we present the regression analyses examining Hypotheses 1.1 and 2.1 about the expected positive co‐variation between invitations and participation levels. Third, we present the regression models examining Hypotheses 1.2 and 2.2 regarding the systematic co‐variation between invitations and stakeholder diversity.

Patterns of government invitations

Figure 3 plots the number of invitations per policy act type. Legislative proposals and government reports have an identical median number of invitations, while the number of invitations for regulations and EU directives is lower.

Figure 3. Boxplot of the distribution of invitations by policy act type.

A Kruskal–Wallis rank sum testFootnote 2 confirms the differences in the number of invitations across policy acts are statistically significant. A pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum test reported in Table 1 helps us investigate which specific pairs of acts differ significantly from each other. Apart from government reports and legislative acts, the differences between pairs are significant at the p < 0.05 level. Norwegian ministries sent significantly more invitations to consultations on legislative proposals compared to government regulations and EU directives, but not relative to governmental reports. This substantiates our argument that bureaucracies have different propensities to send invitations to consultations based on their different (informational and procedural) needs across different acts and further justifies the use of an interaction term between the number of invitations and policy act type.

Table 1. p‐values from pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum test

Invitations and participation levels

To test our expectation about the co‐variation between the number of invitations and participation levels, we fit a negative binomial model due to the over‐dispersed nature of our dependent variable. As a reminder, we expect a systematic positive co‐variation between the number of invitations and participation levels (Hypothesis 1.1). Furthermore, our Hypothesis 2.1 indicates that this positive effect is contingent upon policy act type: the positive co‐variation should be stronger for legislative proposals relative to all other acts. To facilitate model convergence, we exclude five consultations with more than 6000 submissions.

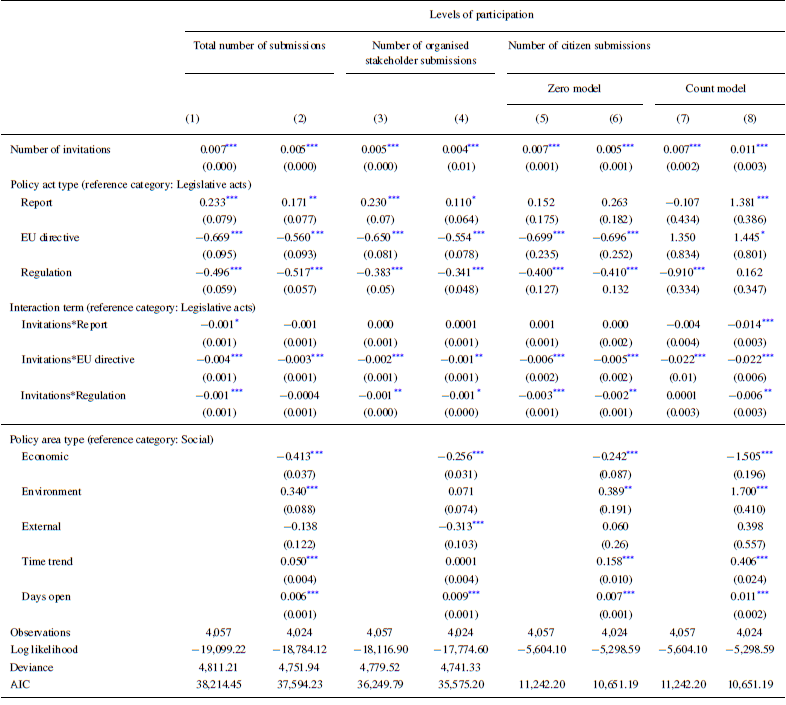

Table 2 presents our analyses employing three specifications of our dependent variable: total number of submissions (models 1 and 2), number of submissions from organisations (models 3 and 4), and number of submissions from citizens (models 5–8). This allows us to account for the theoretical and empirical possibility that more citizens can mobilise for participation than organisations. The variable measuring the level of organisational participation ranges from 0 to 994 (mean 36, median 23, SD 52.6). The variable measuring the level of citizen participation is highly skewed, ranging from 0 to 21,557 (mean 25.8, median 0, SD 440.6).

Table 2. Examining the relationship between invitations, policy act type and levels of participation in consultations

Note: N = 4057 in models without controls because we removed five OPCs that were outliers in terms of participation (more than 6000 submissions). N = 4024 in models with controls because for 33 OPCs there was no correct information for the ‘Days open’ variable (NAs): the website mentions an end date that is earlier than the start date.

Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; OPCs, online public consultations.

* p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

For the analyses examining the level of citizen participation, we fit a hurdle regression model. This is required because many consultations in our dataset (2736; 67.36 per cent) have zero citizen participation. The hurdle regression consists of a zero model and a count model. The zero model predicts the probability that the outcome is larger than 0 (whether there is any citizen participation at all), while the count model predicts the participation of citizens when there is any. In Table 2, models 5 and 6 show the zero‐hurdle model while models 7 and 8 show the count (truncated negative binomial) model.

Looking at the total number of submissions, we find support for Hypothesis 1.1. Model 2 indicates a positive and statistically significant association between invitations and participation: each one‐unit increase in invitations leads to a 0.005 increase in the log of expected participation. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) is 1.005: for each unit increase in invitations, participation increases by about 0.5 per cent. Models examining the number of submissions from organisations (models 3 and 4) and citizens (models 5–8) confirm the robustness of these findings. We discuss these below.

Figure 4 shows the effect of invitations on the predicted counts for our dependent variables keeping the other variables at their means/modes. It illustrates a stronger effect of invitations on the total number of submissions and those from organisations, and a more moderate effect on the number of citizen submissions. This is consistent with the observation that the government sends invitations to organisational and institutional stakeholders. The figure shows that when invitations increase from 0 to 164 (which marks one standard deviation (84) above the average number of invitations (80)), there is an increase in total submissions from 25 to 50, in organisational submissions from 23 to 39 and of citizen submissions from 10 to 19.

Figure 4. The effect of invitations on predicted counts of submissions.

The impact of invitations on participation levels changes across policy act types. However, our results show mixed support for Hypothesis 2.1 positing that the positive association between invitations and participation is stronger for legislative proposals relative to all other acts. The interaction terms in models 1 and 2 show that for government reports, EU directives and government regulations, the impact of invitations is more moderate compared to legislative acts. In model 2, the interaction terms for government reports (−0.001) and regulations (−0.0004) are weak and not statistically significant, suggesting that invitations do not have a substantially different impact on participation for these acts compared to legislative acts. For reports, the conditional effect of invitations indicates a 0.4 per cent increase in participation rate per additional invitation (IRR = 1.004), while for regulations the effect is 0.46 per cent (IRR = 1.0046). For EU directives, the interaction effect is statistically significant. The effect size (−0.003, IRR = 0.997) indicates that each additional invitation increases the participation rate by 0.2 per cent (IRR = 1.002). Invitations increase participation for EU directives, though not as strongly as for legislative acts (0.5 per cent), which supports Hypothesis 2.1.Footnote 3

Our disaggregated analyses for organisations and citizens also suggest mixed support for Hypothesis 2.1. We find slightly stronger support for Hypothesis 2.1 when analysing organisations only (models 3 and 4): the interaction terms for EU directives and government regulations indicate a statistically significant negative effect of invitations on participation compared to legislative acts. In model 4, the coefficient of the interaction term between invitations and act type for EU directives and government regulations is −0.001 (IRR = 0.999). Compared to legislative acts, a one‐unit increase in invitations leads to a decrease in the participation rate of organisations of 0.1 per cent for EU directives and government regulations. For these two act types, the effect of a one‐unit increase in invitations leads to an increase in the rate of organisational participation of 0.3 per cent compared to 0.4 per cent for legislative proposals.

We observe mixed support for Hypothesis 2.1 in models 5–8 examining citizen participation. The interaction term indicates that invitations on legislative proposals generate significantly higher citizen participation relative to all other acts (model 8). There is a statistically significant negative effect for invitations on citizen participation for reports (IRR = 0.99), EU directives (IRR = 0.98) and government regulations (IRR = 0.99) compared to legislative acts. For each unit increase in invitations for EU directives, the participation rate decreases by 1 per cent, while for government regulations and reports the conditional effect is 0, suggesting that invitations have a minimal or no effect on citizen participation in these acts. The general positive effect of invitations on citizen participation is reduced or cancelled for non‐legislative acts, which supports Hypothesis 2.1. For the zero models that explain the probability of any citizen participating (models 5 and 6), we observe a negative effect of the interaction between invitations and act type on citizen presence in consultations on EU directives (−0.01) and government regulations (−0.0003) compared to legislative acts (model 6). The effectiveness of invitations in increasing the likelihood of citizen participation is reduced for these acts relative to legislative proposals.

To further explore the significance and substantial impact of invitations on participation for different policy acts (the logic underpinning Hypothesis 2.1), Table 3 presents the marginal effects of a one standard deviation increaseFootnote 4 from the mean in the number of invitations on participation across policy acts. For legislative acts, a one standard deviation increase in invitations leads to a significant increase in total participation in legislative acts of 31.3. This effect is significant and strong for organisations (16.3) and citizens (16.4). Reports also see a substantial increase in total participation (26.1) driven primarily by the participation of organisations (19.2), with a moderate negative and statistically insignificant effect for citizens (−4.24). Invitations to consultations on EU directives show only a very moderate effect on total participation (5.35) primarily driven by organisations’ submissions (5.21) and a negative albeit not significant effect on citizen participation (−8.38). For government regulations, both citizens (10.1) and organisations (8.67) contribute to the increase in total participation (16.2).

Table 3. Marginal effects for one standard deviation change from the mean in the number of invitations

Note: The results for citizens are calculated based on a truncated negative binomial model.

* p < 0.1; **< 0.05. ***p < 0.01.

Figure 5 shows the predicted counts for all three dependent variables measuring levels of participation for the interaction effect between invitations and policy act type. The increase in invitations matters most for total participation in consultations on legislative proposals and least for consultations on EU directives, with government reports and regulations being somewhere in between. For organisations, the effect of an increase in invitations on participation is larger for governmental reports than for legislative acts, a trend different from the total participation. The larger impact of invitations on participation in consultations on legislative acts could be driven at least partially by citizen mobilisation, while the differences between government regulations and legislative acts are more moderate in explaining organisational participation. However, the impact of invitations on the participation of organisations in consultations on EU directives and government regulations is very low. For citizens, the predicted counts for the interaction term illustrate the very modest effect of government invitations on participation for all policy act types, except for legislative proposals.

Figure 5. Predicted levels of participation for the number of invitations on each policy act type.

Finally, looking at how policy acts types on their own co‐vary with levels of participation across our models in Table 2, we observe that government reports are systematically associated with higher participation levels compared to legislative acts. This association is statistically significant for models examining the total number of submissions (models 1 and 2), submissions from organisations (models 3 and 4) and citizens (model 8). Government regulations and EU directives generate significantly lower participation for all stakeholders and for organisations relative to legislative acts. These policy acts are also systematically associated with a lower likelihood of any citizen presence (models 5 and 6). However, EU directives and governmental reports are systematically associated with increased citizen submissions compared to legislative acts (models 7 and 8). This shows that policy act type also plays an independent role in explaining participation levels that are not linked to the number of invitations. This reinforces our theoretical intuition that policy act characteristics matter for stakeholder participation in consultations.

Among control variables, relative to consultations on social policies, those on environmental policies generate significantly higher participation while those on economic policies significantly lower. This holds across models, although significance levels vary. This reflects the high salience of environmental issues in Norwegian politics (Helliesen, Reference Helliesen2023). Given the size of the coefficients for policy area type, our findings suggest that participation levels are explained to a significant extent by features of the policy process and stakeholders’ interest in the substantive issues tackled in consultations. However, we note the large differences in the number of OPCs across our policy areas, with only 80 consultations on external policies compared to 2346 on social policies. This discrepancy reflects the broad range of policies encompassed by the social policy area (e.g., health, education, labour). Yet, it means that the results for the external policy category should be interpreted with caution because these estimates are based on fewer observations, making them more sensitive to individual cases.

There is a positive and significant association between the number of days a consultation is open and increased participation. This makes intuitive sense, as a longer consultation period gives stakeholders more time to mobilise and participate. Policymakers can use the consultation period as a tool to restrict or expand participation (Potter, Reference Potter2019). However, our analyses show that this effect is quite modest: increasing the consultation period by one standard deviation (32) from the mean (70 days) leads to an average increase of just 9.2 participants.

The time trend shows that Norwegian citizens have become significantly more present in OPCs over the years. The amount of time a consultation is opened for is positively associated with the likelihood of citizen participation and the extent of their participation.

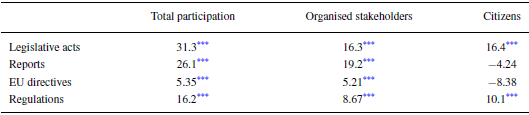

Invitations and stakeholder diversity

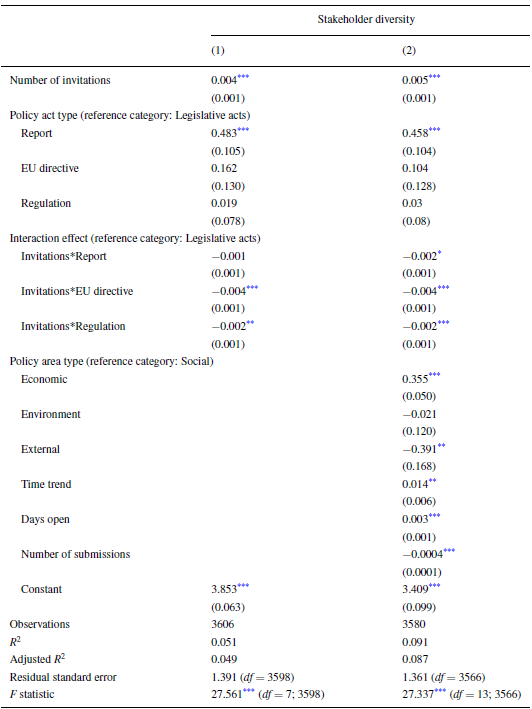

Moving on to examining the relationship between invitations and stakeholder diversity, we present in Table 4 the regression analyses providing a formal test for our expectation that a higher number of invitations is systematically associated with higher stakeholder diversity (Hypothesis 1.2) and that this positive effect is stronger for legislative proposals relative to all other acts (Hypothesis 2.2). Across models, there is a systematic, positive co‐variation between invitations and diversity. Model 2 indicates a moderate increase of 0.005 in diversity for each unit increase in invitations. This supports Hypothesis 1.2.

Table 4. Explaining the co‐variation between a number of invitations, policy act type and stakeholder diversity

Note: OLS model. We analyse OPCs with more than five submissions: 3606. N is smaller in model 2 because, for 26 of 3606 OPCs, we could not identify correct information for the ‘Days open’ variable (NAs).

Abbreviations: df, degrees of freedom; OLS, ordinary least squares; OPCs, online public consultations.

* p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

We also find support for Hypothesis 2.2: the interaction term shows that compared to the effect of invitations on diversity observed in consultations on legislative acts, the effect of invitations on the diversity observed in consultations on other policy acts is negative and statistically significant when all controls are included (model 2). Relative to legislative acts, the interaction term shows a decrease in the effect of invitations on increasing diversity of 0.002 for reports, 0.004 for EU directives and 0.002 for government regulations. Although the interaction terms are negative for the non‐legislative acts, they are not larger in magnitude than the positive main effect of the number of invitations on observed diversity. A one‐unit increase in invitations is associated with a 0.003 increase in diversity for reports and regulations and 0.001 for EU directives. Overall, a higher number of invitations tends to increase diversity across all types of policy acts, but the effect is less pronounced for all non‐legislative acts.

To illustrate the conditional effect of invitations on diversity, Figure 6 presents the predicted stakeholder diversity for our interaction terms. It indicates a moderate positive effect of invitations on diversity for consultations on legislative acts. For government reports and regulations, invitations have a positive, yet less pronounced, impact on diversity. For invitations on EU directives, the effect on diversity is weak as shown by the nearly flat line.

Figure 6. Predicted stakeholder diversity for the interaction terms between the number of invitations and policy act type.

The independent effect of policy act type on stakeholder diversity is relatively moderate, with no statistically significant differences between government regulations, EU directives, and legislative acts. Only government reports generate submissions from significantly more diverse stakeholders than legislative acts.

Regarding our controls, although relative to consultations on social policies, the ones on economic policies generate significantly less frequent stakeholder participation, as indicated by our analyses in Table 2, they seem to attract, on average, the participation of more diverse stakeholders. Consultations on external policies are attended by a significantly less diverse stakeholder pool than those on social policies. The time trend and the number of days for which the consultation is open are systematically and positively associated with stakeholder diversity. The total number of submissions at the consultation level has a slight negative effect, suggesting that increased participation is associated with slightly decreased diversity.

Robustness checks

Previous research indicates that ministries can develop over time strong relationships with some policy insiders or corporatist actors (Lundberg, Reference Lundberg2013; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2015). This might lead ministries to rely on the same invitation lists over time, potentially affecting both their invitation practices and stakeholders’ participation. To address this possibility, we run robustness checks for our models by including ministry fixed effects and ministry‐specific time trends. We present these in Tables A7–A10 in the Online Appendix. These additional analyses confirm our main findings, demonstrating that our results remain stable when accounting for ministry‐specific patterns.

Conclusions

We examined the extent to which government invitations to consultations help explain the patterns of stakeholder participation in open public consultations. Although government invitations are a key consultation design feature, their quality of fostering increased and diverse participation has been only posited theoretically but not empirically assessed in systematic, large‐n research designs. We addressed this research gap with the help of a new dataset of all OPCs organised over a period of 14 years by the Norwegian government.

We found that government invitations co‐vary systematically with patterns of stakeholder participation. A higher number of invitations is systematically associated with a higher number of stakeholder submissions, higher participation of organisations and citizens, a higher likelihood that any citizen participates, and higher stakeholder diversity. Although the impact of the number of invitations on participation is relatively modest in substantive terms, this supports the view that policymakers’ outreach efforts can foster a more inclusive and pluralistic consultative and public policymaking process. These findings are consistent with those of Lundberg (Reference Lundberg2013, 72) who found that in Sweden the practice of government invitations does not negatively impact pluralism and ‘encourages a multitude of organisations to participate’ in policymaking.

Our findings also show that decisions about consultation designs are fundamental for how consultations can address and redress issues of unequal participation and bias in interest representation (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Blom‐Hansen and Senninger2021; Fraussen et al., Reference Fraussen, Albareda and Braun2020). This has important policy implications insofar as it shows that policymakers’ outreach efforts can make a difference in how bureaucracies democratise their policymaking processes and how the public is ‘brought into’ this. This also matters because OPCs constitute a relatively low‐cost instrument that policymakers can deploy to democratise and diversify their policymaking and fulfil their informational and legitimacy needs. Our study shows that through their power to invite stakeholders to consultations, policymakers have some leverage over how stakeholders mobilise for participation in policymaking. Particularly relevant here is the finding that the number of invitations (sent mainly to organisations) increases significantly the likelihood of any citizen participating in consultations. This indicates that invitations matter for mobilising citizens’ participation despite not being directly addressed to them, which in turn highlights that organisations (recipients of invitations) can act as an activation belt for at least parts of citizens’ participation in OPCs. One relevant example is the consultation on the potential opening of areas on the Norwegian continental shelf for seabed mineral activities organised by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy in 2022. The ministry extended 158 invitations. The environmental organisation World Wildlife Fund (WWF) was among the recipients. This organisation mobilised its individual members to participate in the OPC so that a large amount of the submissions made by citizens to this consultation were almost identical, and some even indicated WWF as the source of their text. In total, 980 individuals and 85 organisations participated in this consultation. Following this consultation, during the parliamentary debate stage of this initiative in November 2023, WWF organised a public campaign asking citizens to sign an online letter addressed and later delivered to the Norwegian parliament. This letter had content that was very similar to that of the individual submissions made by citizens earlier in the OPC, providing further evidence that WWF encouraged and supported citizens’ participation in the 2022 consultation.

Our finding about the impact of invitations on citizen participation is noteworthy and suggests an important direction for future research: investigating the specific mechanisms through which government invitations addressed to organisations impact and encourage citizen participation in consultations. This could add important insights to the research examining the role of interest organisations as intermediaries between the public and policymakers (Rasmussen & Reher, Reference Rasmussen and Reher2019) and research investigating how interest organisations influence citizens (Junk & Rasmussen, Reference Junk and Rasmussen2024).

We note, however, an important caveat of our study with respect to citizen participation: the information available about participating citizens does not allow identifying their socio‐economic background or education. Therefore, it is difficult to assess the extent to which these citizens are representative of the broader Norwegian population or represent a group of ‘elite citizens’, highly educated and possessing the time and informational resources to engage in consultations. Thus, it is difficult to assess the impact of invitations on the diversity of participating citizens.

Our analyses indicate that the size of the impact of the government's demand for participation is relatively modest on observed participation patterns when considering other contextual factors. Stakeholders participate in a way that reflects strategic behaviour and corresponds to the political salience of the policy act and their interests in substantive policy issues. Whether an act is a legislative proposal or not moderates to a certain extent the impact of invitations on participation and covaries systematically with observed levels and diversity of stakeholder participation. This is important insofar as these are the acts that executives draft but need legislative approval and face the distinct possibility of legislative amendments prior to this. Strong stakeholder participation provides the executive with important opportunities to legitimise and build broad stakeholder support for its proposals, but also important lobbying and policy‐shaping opportunities for stakeholders.

Lastly, policy area type is a strong and systematic predictor of participation and diversity, a finding consistent with the research highlighting the impact of policy context on stakeholder engagement in consultations (Rasmussen & Carroll, Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014; Røed & Wøien Hansen, Reference Røed and Wøien Hansen2018).

Several limitations mark our study and uncover venues for future research. First, we did not have information about which organisations and what type of organisations are at the receiving end of government invitations in our dataset. This is due to the high number of invitations sent by the Norwegian ministries (325,332) and the lack of systematic official information about the organisational profiles of the actors. Including information about the diversity of actors invited to consultations would allow a more refined way to assess how invitations shape participation and would examine the extent to which the diversity characterising the invitee list correlates systematically with higher stakeholder participation and diversity. Second, although we find that more invitations increase stakeholder diversity, our current analyses do not reveal key characteristics of the participating organisational stakeholders, such as their level of policy insiderness or privileged position in the Norwegian interest representation system. Our diversity index does not capture whether the observed interests are represented by organisations that are new participants, or policy insiders and frequent participants in executive policymaking (as found in Sweden by Lundberg, Reference Lundberg2013) or organisations that are ‘strong corporatist players’ with longstanding relationships with policymakers within certain policy domains as found in Denmark by Rasmussen (Reference Rasmussen2015). Future research could examine the actor constellations underpinning the observed diversity of interests in Norwegian OPCs and investigate the extent to which these are attended by organisations that enjoy special status in Norwegian politics and policymaking. Third, our dataset does not include fine‐grained measures of the public and media salience at the policy act level that would allow us to test an argument proposed in the literature on stakeholder engagement in policymaking that highlights the important role of public or media salience in explaining levels of participation in consultations. Fourth, while our study is interested in examining the co‐variation between the number of invitations and patterns of participation, a relevant and interesting research question is that of what explains the variation in the number of invitations extended across policy acts and policy areas. This would provide further insights into the broader policy context in which government invitations shape participation. Finally, our study focuses on one country with a strong corporatist tradition. Despite its move towards a more pluralist system of interest representation, the legacy of Norwegian corporatism could shape the relationship between invitations and participation insofar as ministries in former corporatist systems may possess more consolidated and systematic databases of relevant stakeholders to invite and have stronger administrative traditions and better‐established procedures for deploying this consultation design mechanism than in countries with more pluralist traditions, which lack the legacy of corporatist arrangements. Similarly, stakeholders may be more responsive to these invitations in countries with former corporatist settings because of a long‐standing tradition of being frequently consulted by the government (Lundberg, Reference Lundberg2013). A question remains, therefore, if government invitations matter in the same way and to the same extent for patterns of stakeholder participation in countries that lack the institutional and organisational legacies of corporatism.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the European Research Council through the ERC‐STG‐2018 research project CONSULTATIONEFFECTS (grant no. 804288). We gratefully acknowledge this funding. We are grateful for the comments received from our anonymous reviewers, Cornelius Cappelen, Raimondas Ibenskas, Alexander Verdoes and the participants in the workshops at the NOPSA 2024 conference and the 2025 National Norwegian Political Science Conference.

Data availability statement

Data and replication code are available a: Bunea, Adriana; Nørbech, Idunn, 2025, ‘Replication Data for: Do government invitations to consultations shape stakeholder participation in public policymaking?’, https://dataverse.no/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.18710/HZIBBH DataverseNO.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix