Introduction

The issue ownership theory is one of the most prominent theoretical frameworks to explain voter and party behaviour (Bélanger & Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008; Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Egan, Reference Egan2013; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). In terms of voter behaviour, the theory predicts that voters support parties which they perceive to be owners of the issues that are important to them (Bélanger & Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008). On the party side, parties are expected to emphasise the issues on which they have a competitive advantage over other parties (Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983). Given the weakening ideological ties between parties and voters, it has been argued that issue ownership increasingly structures voters’ electoral decisions (Walgrave & De Swert, Reference Walgrave and De Swert2007).

Research on issue ownership has paid much attention to the measurement and different dimensions of the concept (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2012, Reference Walgrave, Van Camp, Lefevere and Tresch2016, Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2020). One topic that has received somewhat less attention is how parties become seen as the owner of an issue. While several studies have examined the individual‐level correlates of citizens’ perceptions of issue ownership (Brasher, Reference Brasher2009; Craig & Cossette, Reference Craig and Cossette2020; Stubager & Slothuus, Reference Stubager and Slothuus2013), we know less about what parties can do to build an image as issue owners (but see Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2024; De Bruycker & Walgrave, Reference De Bruycker and Walgrave2014; Walgrave & Soontjens, Reference Walgrave and Soontjens2019). Some work has suggested that parties’ issue ownership is fairly stable (Seeberg, Reference Seeberg2017a), while others find considerable variation (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Dahlberg and Martinsson2015; Dahlberg & Martinsson, Reference Dahlberg and Martinsson2015). Such patterns lead to the question whether this variation is systematic and whether and how parties can act to shape their reputation as issue owner? We shed light on this question with an observational and experimental study into the sources of parties’ issue ownership.

For theorising the sources of issue ownership, we focus on three important aspects of party behaviour: parties’ attention for the issue, the extremity of their position on the issue and their performance on the issue (Egan, Reference Egan2013; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996; Seeberg, Reference Seeberg2017a). We focus on these factors because parties have a substantial level of control over them. First, we assume that parties can actively show commitment to an issue by emphasising it strongly in their election platform (Walgrave & De Swert, Reference Walgrave and De Swert2007). Second, we test whether taking more extreme positions on an issue increases the visibility of parties’ position among the public leading voters to more strongly associate the party with that issue (Wagner, Reference Wagner2012). Third, it can be argued that to build and preserve a reputation as the owner of an issue, parties have to show that they are able to perform well on the issue by providing effective policy (Bélanger, Reference Bélanger2003). We argue and empirically validate whether these three aspects of party behaviour – attention, position and performance – indeed contribute to parties’ issue ownership.

Our first contribution is empirical, combining different possible sources of competence reputation in one study and providing a systematic test of existing and new explanations. Second, we innovate theoretically by testing whether these mechanisms work differently for opposition and incumbent parties, further distinguishing incumbent parties with and without the minister's portfolio on the issue. Our third contribution is methodological, as we conducted two studies to test our expectations empirically. Study 1 uses the most comprehensive dataset on issue ownership available – combining data from 130 parties in 108 elections and 18 countries spanning five decades. To gain causal leverage, Study 2 is a pre‐registered conjoint experiment, in which respondents judged party profiles based on their attention, position and performance on an issue that was important to them. The results of both studies indicate that parties can build issue ownership mainly by focusing strongly on the issue. Opposition parties in particular have much to gain from strategically emphasising issues. Furthermore, extreme parties are generally considered to be less an owner of an issue than more moderate parties. Finally, the observational analysis suggests that good (economic) performance is strongly positively correlated with issue ownership for incumbent parties – especially when they hold the minister portfolio on the issue – and vice versa for parties in opposition, but we only find suggestive evidence regarding performance in the experiment.

Issue ownership and its sources

The concept of issue ownership was introduced in the literature by Petrocik (Reference Petrocik1996, p. 826), who defined it as follows:

[A] reputation for policy and program interests, produced by a history of attention, initiative, and innovation toward these problems, which leads voters to believe that one of the parties (and its candidates) is more sincere and committed to doing something about them.

While this definition has laid the groundwork for most of the research on the topic, it is important to mention that in empirical research different dimensions of issue ownership have been identified, including associative and competence ownership (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2012, Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2020). In our empirical analyses, we focus mostly on parties’ issue competence reputations – the most widely investigated dimension of issue ownership. Therefore, whereas our theoretical ambitions address issue ownership more broadly, our arguments mostly focus on competence reputations specifically.

The definition by Petrocik (Reference Petrocik1996) highlights the historical roots of issue ownership which could be taken to imply that competence reputations are a fixed characteristic of parties. However, previous research has found that perceptions of issue ownership are quite dynamic (Bélanger, Reference Bélanger2003; Dahlberg & Martinsson, Reference Dahlberg and Martinsson2015; Damore, Reference Damore2004; Holian, Reference Holian2004), even over the course of an election campaign (Petitpas & Sciarini, Reference Petitpas and Sciarini2018). Hence, even though we acknowledge that parties have long‐standing reputations with regard to certain issues, they also have to continuously defend their advantage (Dahlberg & Martinsson, Reference Dahlberg and Martinsson2015). Our data allow for a test of the stability of competence reputations and descriptive results reported in online Appendix A show that there is indeed considerable within‐party variation in these perceptions. It is therefore clear that there is variation in people's perceptions of parties’ competence, and we focus on these short‐term dynamics, which have the potential to accumulate and bring about enduring changes in parties’ issue reputations.

We consider three main sources of parties’ competence reputations, following the three dimensions of issue ownership that are often distinguished: issue attention, position and competence (Lefevere et al., Reference Lefevere, Seeberg and Walgrave2020; Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2020). Our focus is thus similar to that of Egan (Reference Egan2013), who examines issue priorities, policies and performance of the parties in the United States to explain their levels of issue ownership. Building on this work, in the following sections we elaborate on each of these three possible sources of issue ownership and we formulate hypotheses with regard to their effects. We also expand on the work of Egan. First, we take the arguments a step further by also considering between‐party heterogeneity. Second, at an empirical level, we move beyond the U.S. context by using a comparative design and beyond observational analyses by using a novel conjoint experiment.

Parties’ emphasis on their core issues

The first source of parties’ competence reputation is their emphasis on issues (Dahlberg & Martinsson, Reference Dahlberg and Martinsson2015). Most existing research focuses on this mechanism and has found that parties can gain or keep ownership by emphasising it strongly in their own communication (De Bruycker & Walgrave, Reference De Bruycker and Walgrave2014; Holian, Reference Holian2004). Focusing on the Belgian case, Walgrave and de Swert (Reference Walgrave and De Swert2007) found that parties are more likely to be considered the owner of an issue when they actively emphasise their core issues and also when the media emphasises parties’ handling of these issues. Others have shown that parties can ‘steal’ the ownership of another party through the attention they give to an issue (Tresch et al., Reference Tresch, Lefevere and Walgrave2015; Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Nuytemans2009).

From work along these lines, we know that media coverage and parties’ own communication can lead voters to perceive parties as competent on issues. Here, our focus is on how parties themselves can act strategically to build a reputation as issue owners, leading us to focus on the role of parties’ own communication captured in manifestos. Party platforms inspire parties’ press releases during the campaign (Tresch et al., Reference Tresch, Lefevere and Walgrave2018), implying they are a good indicator of how much a party wishes to emphasise a certain issue – irrespective of how successful they are in spreading this message. Furthermore, issue attention in manifestos is associated with future parliamentary questions (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Nyhuis, Block and Velimsky2024).Footnote 1 While the connection between issue attention in manifestos and ownership has been documented by earlier research, not all previous research has found it to matter. Experimentally investigating issue ownership perceptions, Stubager and Seeberg (Reference Stubager and Seeberg2016), for instance, did not find effects of receiving information about parties’ priorities of an issue. We, therefore, first test the issue attention hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The more a party emphasises an issue in its manifesto, the better its competence reputation on that issue.

Position taking on issues

Besides deciding which issues to talk about, parties also need to take positions on a range of issues, which they do strategically (Wagner, Reference Wagner2012) and which can shape their competence reputations. Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2024) show that parties gain economic ownership when they are perceived to move to the political right. In our analyses, we consider a broader set of issues than only the economy, and from such a broader perspective, too, there are reasons to expect that extremeness on an issue increases the party's perceived competence on it.

First, when a party takes more extreme positions, it is likely to receive more media attention than moderate parties (Mullainathan & Shleifer, Reference Mullainathan and Shleifer2005). In turn, the media attention for a party on a specific issue could strengthen the perceived link between the party and this issue, and voters might take this stronger displayed commitment of the party as a signal of its competence on this issue. Second, Lefevere et al. (Reference Lefevere, Seeberg and Walgrave2020) found that when parties attack another party's position by labelling it as extreme, voters take this as a sign that the attacked party is strongly committed to this issue. Wagner (Reference Wagner2012) developed this argument explicitly when arguing that parties have an incentive to take more extreme – rather than centrist – positions because doing so allows them to differentiate themselves from other parties. This helps the party to establish a strong association as owner of that issue. Providing evidence for this claim, Ezrow (Reference Ezrow2008, p. 207) shows that niche parties – that focus on one or a small set of issues – gain electoral support when they hold a more extreme position on their core issue (see also Mauerer et al., Reference Mauerer, Thurner and Debus2015). We hence hypothesise that parties that take a more extreme position on an issue will be perceived as being more competent on it.

Hypothesis 2: The more extreme the position of a party on an issue, the better its competence reputation on that issue.

An alternative hypothesis would be that the association between the ideological position of a party and its competence reputation is non‐linear or even reverses at the ideological extremes. Johns and Kölln (Reference Johns and Kölln2020), for instance, show that centre parties are considered more competent in general. However, when it comes to competence on issues specifically, we follow the argumentation above and reason that an extreme position on an issue signals a party's devotion to it. The analysis below will shed new empirical light on the validity of our hypothesis and that of the alternative hypothesis.

Party performance

A third element of parties’ behaviour, we theorise that has the potential to shape their ownership over certain issues, is the extent to which a party delivers on the issue by conducting effective policies that lead to desirable outcomes (Bélanger & Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008). Parties’ history of decision‐making has been theorised to shape their competence reputations (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996) because decision‐making is a way for parties to show that they can ‘walk the talk’ and deliver on their promises: ‘logic dictates that for a party to make the greatest gains in credibility on an issue, it should deliver real results’ (Brasher, Reference Brasher2009, p. 86).

Parties can deliver on issues in several ways. For instance, they can fulfil their campaign promises to have special attention for certain issues by putting them high on the agenda after the elections. There is evidence that parties do this. Gross et al. (Reference Gross, Nyhuis, Block and Velimsky2024), for example, show that in their parliamentary activities parties focus on issues to which they gave more attention during the campaign. Other research shows that parties take up their promises in future parliamentary work, such as parliamentary questions and legislative activities (Otjes & Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2017; Sulkin, Reference Sulkin2009). Here, we do not consider delivering in terms of agenda‐setting but focus on more downstream outcomes – that is, whether or not the desirable outcome was realised – because we argue that this is closest to the ‘results’ that have been argued to be important to build competence reputations (Brasher, Reference Brasher2009). For the U.S. case, investigating time‐series data of issue ownership between the Democrats and Republicans, Brasher (Reference Brasher2009) showed that parties’ issue handling reputations reflect their institutional performance. Investigating the Canadian case, Bélanger (Reference Bélanger2003) similarly found that objective economic indicators are significantly associated with perceptions of incumbent parties’ competence in handling these issues. We thus expect that a better performance on an issue correlates positively with competence reputations on this issue:

Hypothesis 3: The better the track record of a party on an issue, the better its competence reputation on that issue.

Between‐party heterogeneity

We also expect there to be substantial between‐party heterogeneity: we argue that there will be differences between incumbent parties and opposition parties. These two types of parties have different interests during an electoral term, and they have been found to use their agenda‐setting power strategically according to their position (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010; Thesen, Reference Thesen2013). Election manifestos are structurally different between incumbent and opposition parties (Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Müller, Praprotnik and Winkler2018) and can, therefore, also relate differently to their competence reputation. In addition, governing parties have an advantaged position for sending out their messages and can make stronger claims on being able to act on those messages. As indicated by Brasher (Reference Brasher2009, p. 72), ‘Control of an institution of government provides each party with not only a communication platform but also the institutional resource to actually take action which gives their words greater credibility’. Incumbent parties’ performance might also be monitored more closely; apart from finding a main effect of being in office, Bélanger (Reference Bélanger2003) finds that economic indicators matter more for perceptions of competence in handling the economic issues for parties in office than for opposition parties. It can, therefore, be expected that the mechanisms described above are more prevalent for parties in office. When several parties are in coalition, we furthermore expect to see differences depending on which party holds the portfolio relating to a specific issue. Previous work has shown that people are able to distinguish different parties based on their positions within the government. Duch and Falcó‐Gimeno (Reference Duch and Falcó‐Gimeno2022, p. 3) argue that ‘individuals interpret institutional compartmentalization as a signal of the agenda‐setting power of parties in coalition cabinets’. They also find that voters are more likely to punish a party for bad economic performance when it holds the finance minister position in a context of compartmentalised decision‐making. Investigating the Italian case, Plescia (Reference Plescia2017, p. 330) concludes that ‘parties seem to suffer in line with ministerial responsibilities’. Finally, Plescia and Kritzinger (Reference Plescia and Kritzinger2022) show that coalition conflict over an issue reflects more negatively on the party that controls the ministry of that issue. All these contributions indicate that citizens are informed about parties’ portfolios and that performance on specific issues reflects on the parties that hold ministerial responsibilities for them. Therefore, while theoretically we are mostly concerned with testing general mechanisms, we also test in an exploratory fashion whether there is heterogeneity in the effects, distinguishing opposition parties from incumbent parties with and without the government portfolio on the respective issue. Looking at party status as a moderating factor, it is important to note that we do not test the direct effects of being in office on competence reputations, which we leave to future research.

In the empirical part of the paper, we present the results of two studies. Study 1 uses observational data stemming from public opinion surveys, party manifestos and official government statistics, constituting the most extensive dataset on competence reputations available. Study 2 reports on an original and pre‐registered conjoint experiment designed to put the results of the observational study to a causal test.

Study 1: An observational assessment of the sources of issue ownership

Data and variables

Our dependent variable for the observational study captures parties’ competence reputation on specific issues. To operationalise this variable, we rely on a publicly available dataset that was created by Seeberg (Reference Seeberg2017a, Reference Seeberg2017b) (and see also Adams et al. Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2024). The dataset contains information on the ownership over 35 issues in 17 countries, coming from national election studies.Footnote 2 We updated the dataset by incorporating the most recent election studies available in the countries covered in Seeberg's data and added information on competence reputations from the Icelandic Election Studies. Overall, we have information on perceptions of ownership over 35 issues in 108 elections in 18 countries in the period 1969–2019.Footnote 3 Parties’ perceived competence is measured at the party–issue level and indicates the proportion of respondents in an election study who considered the party most competent on the issue under investigation. The data show substantial variation in parties’ reputations as evidenced by the observed range of the indicator, which runs from 0 to 97.26 (the highest score is observed for the U.S. Democratic Party on the issue of the environment in 2016).Footnote 4 The data are stacked, with party–issue combinations nested in years and nested in countries (for a similar data structure, see Bélanger, Reference Bélanger2003).

Given that the data combine information from different national election studies, the exact question wordings unavoidably vary somewhat (see Seeberg, Reference Seeberg2017a). In most election studies, competence reputations were measured by asking respondents which party they thought was best at dealing with a list of pre‐selected issues. Alternatively, respondents were first asked which issue was most important to them and, subsequently, which party would be best at dealing with it. While there is some variation in question wording, the measures mostly capture the competence dimension of issue ownership (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2020). We think of this as an advantage because this focus on competence implies that the measures of issue ownership match our theoretical framework and our focus on competence reputations.

We include three main independent variables (see online Appendix C). The first independent variable captures the attention that parties have for specific issues in their manifestos. We rely on manifestos because of data availability. Reassuringly, however, in their study on Belgium, Walgrave and De Swert (Reference Walgrave and De Swert2007) found that parliamentary work did not add any explanatory power for explaining issue ownership when attention in party manifestos is accounted for. We use the data of The Manifesto Project (MARPOR) (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2021), which relies on a hand‐coding of mentions of issues on the quasi‐sentence level, resulting in a measure of the proportion of the manifesto that is devoted to different topics. We capture attention for issues as the sum of a party's issue mentions, combining positive and negative mentions of issues (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) to a measure indicating the proportion (in percentages) of a party manifesto that is devoted to an issue.Footnote 5

The second main independent variable captures the extremity of parties’ positions. We create two different measures: first, we focus on the extremity in terms of parties’ general left‐right position, as a ‘super issue’ (Van der Eijk et al., Reference Van der Eijk, Schmitt, Binder and Thomassen2005).Footnote 6 Acknowledging the limitations of a single left–right dimension, we also assess the role of the extremity of parties’ positions on more specific issues. To calculate parties’ ideological positions, we again use the MARPOR data, which provides us with comparable estimates of the positions of all parties and elections covered in the dataset. We follow Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) and log‐transform the MARPOR estimates, both for the general left–right scale and for more specific issue domains. To create a measure of extremity of these positions, we then take the absolute value of this scale.Footnote 7

For positional measures on more specific issues, we opted to include only those issues for which there is a very close match between MARPOR categories and the issues in the ownership data: education, European Union, welfare and environment, excluding the other issues that are included in all other analyses (see online Appendix D).Footnote 8 We again apply a log‐transformation to capture positions to calculate the absolute value of the position of parties on the issue and each time link it to the same issue of the ownership data for every country‐year–party dyad.

The third main independent variable is a measure of performance. Following Bélanger (Reference Bélanger2003), and building on the literature on economic voting, we use information on unemployment rates. This means that our observational assessment of the role of performance is limited to economic issues and unemployment more specifically. The economy is a prime example of a valence issue, where everyone agrees on what the goal should be (Stokes, Reference Stokes1963). We believe that unemployment rates capture the performance of a party on the economy quite well. It is the economic indicator that is the easiest to perceive by voters, and citizens appear to swiftly update their economic perceptions when there are changes in unemployment rates (Conover et al., Reference Conover, Feldman and Knight1986, Paldam & Nannestad, Reference Paldam and Nannestad2000, Stiers & Kern, Reference Stiers and Kern2021). Even though it can be debated whether fluctuations in economic indicators really reflect how well parties perform, we know from the literature on economic voting that citizens connect economic conditions and party performance (Dassonneville & Lewis‐Beck, Reference Dassonneville and Lewis‐Beck2014; Duch & Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis‐Beck & Stegmaier, Reference Lewis‐Beck and Stegmaier2000). A limitation of a focus on economic performance is that it captures the performance of incumbents, not those of opposition parties. We elaborate on this point in the conclusion. We retrieve unemployment data of the year leading up to the elections from the World Bank and match it with the data on competence reputations.Footnote 9 For this purpose, we only link the unemployment rates to entries in the dataset that capture perceived competence over the issue of unemployment specifically.

We furthermore include incumbency status to examine party‐level heterogeneity. The measure distinguishes parties that were in opposition during the previous term, parties in government but without holding the minister portfolio on the respective issue and parties in government holding the minister portfolio. Information on which parties hold minister portfolios connected to specific issues is derived from the WhoGov database (Nyrup & Bramwell, Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). More details are included in online Appendix H.

Methods

To model the associations between competence reputations and our key independent variables, we use linear models with, as a unit of analysis, the party–issue dyad. We argue on theoretical grounds that more attention for a certain issue increases a party's competence reputation on this issue, but parties can also emphasise those issues on which they already hold stronger issue reputations – introducing some reverse causality in the models. Previous research has shown that parties are more likely to talk about issues on which they have ownership (van der Brug & Berkhout, Reference Brug and Berkhout2015). Parties can also focus their policy efforts on their strongest domains. To address this issue of endogeneity to some extent, and to account for autocorrelation, we estimate panel models with fixed effects on the level of party–issue combinations, implying the remaining variation explored in the model concerns changes within the party–issue level.Footnote 10 This approach allows us to model baseline differences in issue emphasis and competence reputations between parties (e.g., due to differences in the size and popularity of parties), accounting for reverse causation in the model. Furthermore, we cluster the standard errors by country.

We estimate two models for each variable of interest: a first one focusing on the overall correlation between our measure of interest and issue ownership and a second including an interaction between our measure of interest and the indicator of a party's position as opposition party, incumbent party without the issue‐specific minister portfolio or incumbent party with an issue‐specific minister portfolio.

Results

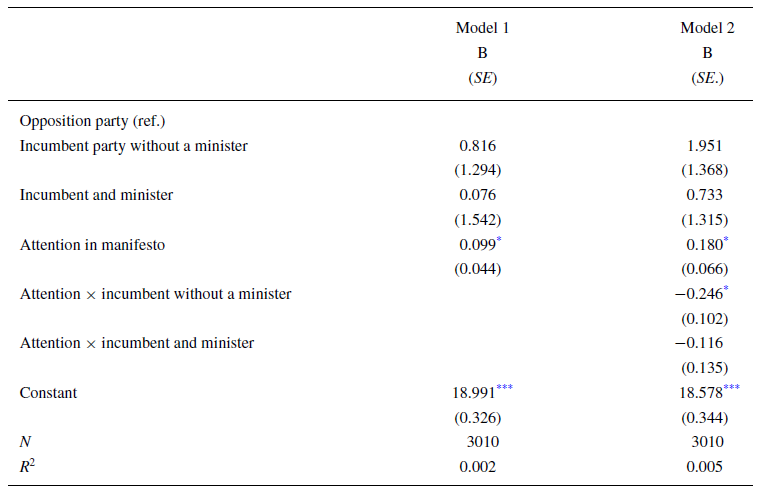

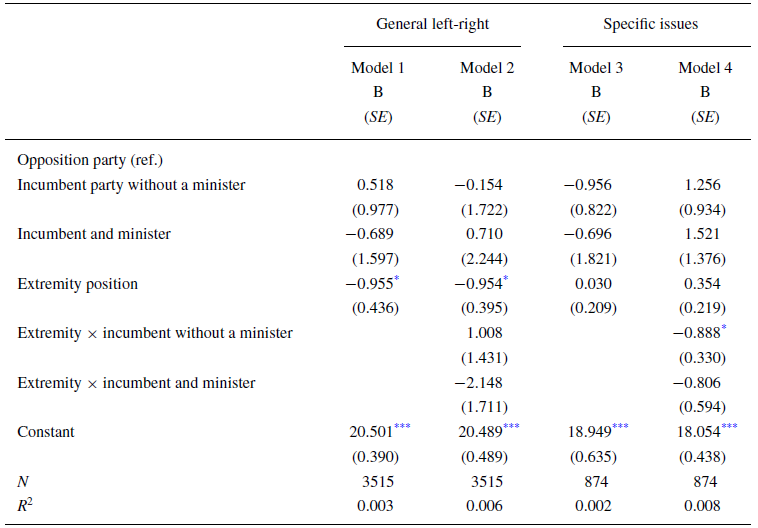

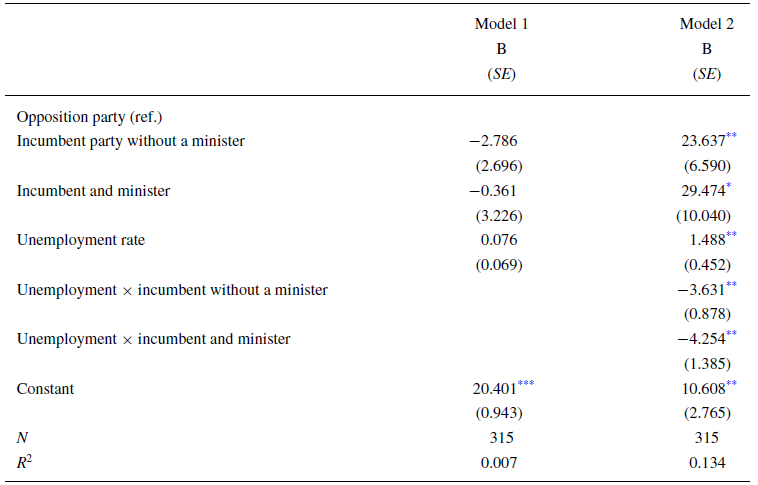

In the first step, we assess whether more attention to an issue in a party's manifesto is associated with better competence reputations on that issue (Hypothesis 1). Table 1 shows a positive association between issue attention in a manifesto and issue ownership. Accounting for parties’ stable issue reputations (through party fixed effects), we find that with an increasing proportion of the manifesto devoted to an issue comes an increasing public perception of the party's issue competence on this issue: parties gain about 0.10 percentage points perceived competence when they spend one additional percentage point of their manifesto on the issue. This indicates that competence reputations fluctuate considerably and are not only stable and slow‐moving party characteristics. The results in Model 2 provide indications of differences in the correlation between attention and competence between the different groups of parties. To ease the interpretation of the results, the average marginal effects of a one‐unit increase in issue attention – by incumbency type – are displayed in Figure 1.

Table 1. Explaining competence reputations with manifesto attention

Note: Entries are unstandardised ordinary least squares (OLS) coefficients, and standard errors (SE) are given in parentheses.

Significance levels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 1. Average marginal effects of issue attention.

Note: The figure shows the average marginal effects of issue attention for different groups of parties. Results based on coefficients in Table 1 Model 2.

Figure 1 shows that for every increase of a percentage point in attention for a certain issue in their manifesto, an opposition party receives almost 0.18 percentage points higher competence reputation. For incumbent parties, we do not find a significant association – irrespective of whether this party holds the ministerial portfolio on the issue or not. This is a surprising finding: while we did not have a clear expectation regarding the heterogeneous effects of issue attention between types of parties, theories of agenda setting pointed in the direction of better opportunities for incumbent parties to spread their message, which would result in stronger effects for governing parties. The results suggest the opposite, as issue attention only seems to matter for opposition parties. Below we examine whether the competence reputations of incumbent parties are, instead, shaped by other sources of party behaviour.

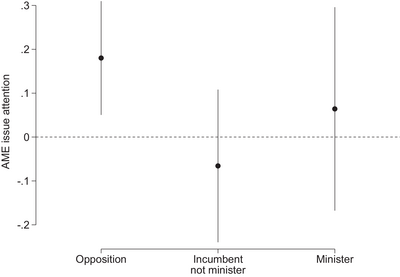

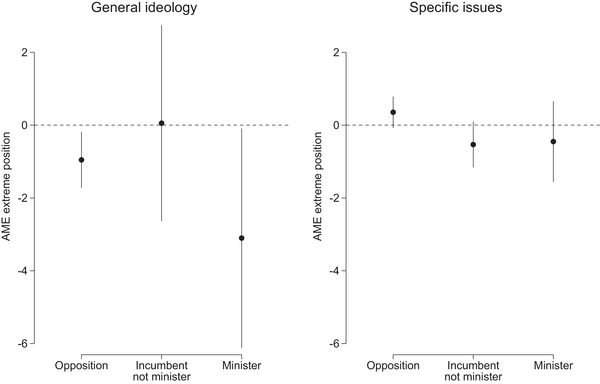

Second, we test whether parties that take a more extreme position on issues are considered more competent on that issue (Hypothesis 2). Contrary to our hypothesis, Table 2 shows a negative association between extreme positions on the general ideological continuum and competence reputations. Figure 2 shows that this association exists for opposition parties and for incumbent parties that hold the minister position on the issue while it is almost zero for incumbent parties without the minister portfolio. We do not find a significant association for extremity on specific issues, but we note that the association between extremity and competence is significantly smaller for incumbent parties without the ministerial position than for parties in opposition. Looking at Figure 2, while the uncertainty around the estimates for opposition parties and incumbent parties without a minister is too large for the estimates to reach statistical significance, the results indicate opposite patterns for incumbent and opposition parties. Hence, while a general extreme ideological position seems to negatively influence the competence reputations of most parties, there is suggestive evidence that opposition parties can gain perceived competence when they take an extreme position on specific issues.

Table 2. Explaining competence reputations with party positions

Note: Entries are unstandardised OLS coefficients, and standard errors (SE) are given in parentheses.

Significance levels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2. Average marginal effects of extreme position taking.

Note: The figure shows the average marginal effects of extreme issue positions for different groups of parties. Results are based on coefficients in Table 2 Model 2 (left) and Model 4 (right), respectively.

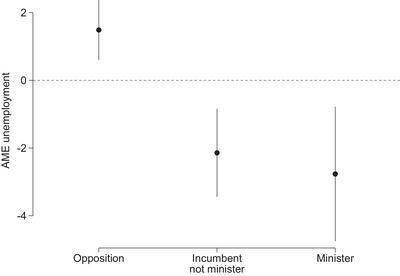

As a last mechanism, we turn to the role of performance (Hypothesis 3). The results are summarised in Table 3. In these models, ‘holding the minister portfolio’ refers to holding the portfolio of unemployment – in this case the WhoGov category ‘Labor, employment & social security’ (see online Appendix H for details).

Table 3. Explaining competence reputations with unemployment

Note: Entries are unstandardised OLS coefficients, and standard errors (SE) are given in parentheses.

Significance levels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 3 shows no overall effect of unemployment rates on perceived competence. However, as visualised in Figure 3, when the unemployment rate increases (i.e., bad incumbent performance), opposition parties are perceived to be more competent on the issue of unemployment. In contrast, when unemployment levels decrease (i.e., good incumbent performance), it is incumbent parties that gain a better reputation; for every percentage point decrease in unemployment, incumbent parties gain about 1.9 percentage points in perceived competence over unemployment.Footnote 11 The association is stronger for parties that hold the ministerial portfolio of labour with an average marginal effect of 2.6 percentage points.Footnote 12 The sign for opposition parties is reversed as could be expected: as competence reputations are distributed among all parties running in an election, opposition parties logically gain the reputation that incumbent parties lose even if they do not have policy control over the issue of unemployment.

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of unemployment rate.

Note: The figure shows the average marginal effects of unemployment rates for different groups of parties. Results are based on coefficients in Table 3 Model 2.

While the analyses reported here use absolute measures of parties’ issue emphasis and extremity, it is possible that their relative emphasis and position are more important (i.e., emphasis and position vis‐à‐vis other parties in the party system). We tested this possibility using a relative measure of issue emphasis (indicating how much more or less space a party devotes to the issue in its manifesto compared to the mean attention of all parties in a country‐year) and of extremity (a measure of how much the position of a party deviates from the mean position of all parties). As can be seen from online Appendix L, the results are not stronger compared to the main analyses that use absolute measures. The main difference is that issue attention is positively associated with competence reputations in the analysis of relative indicators, which is in line with our original argument of increased visibility of these parties.

Study 2: An experimental test of the sources of issue ownership

Study 2 puts the observational results of Study 1 to the test using a design that allows for stronger causal interpretation: a conjoint experiment. The design and analyses of this study were pre‐registered.Footnote 13 The study was reviewed by the ethics board of KU Leuven.Footnote 14

Experimental design and case

Our experimental design consists of two stages (Castanho Silva & Wratil, Reference Castanho Silva and Wratil2023). In the first stage, respondents were asked to indicate which three issues were most important to them from a list of issues (see online Appendix M)Footnote 15 and then how important each of these issues was to them. Our goal with these questions was to select the issue that was most important to the respondent, which was used in the second stage: the conjoint task. This way, the issue used in the conjoint part of the experiment was always important to the respondent, ensuring that individual‐level issue salience was held constant.

The second part was the conjoint choice task, in which we asked respondents to look at the profiles of two hypothetical parties, ‘party A’ and ‘party B’. The choice of hypothetical parties means that respondents judged the parties without strong predispositions so that pre‐treatment attitudes could not affect their answers. As a drawback, this limits the external validity of the design, as in the real world, parties can make explicit use of long‐standing ties with (groups of) voters. However, as it would be impossible to account for all existing (psychological) connections between respondents and existing parties, we opted for maximising the internal robustness of the design. Another drawback is that this design cannot account for the role of media actors in connecting party strategies to the public's perceptions of parties. For example, if extremity shapes perceptions of issue competence solely because more extreme parties receive more media coverage, these effects would not be visible in the experiment. The advantage of using hypothetical parties, however, is that it allows us to obtain estimates of the unmediated effects of party strategies – and therefore of the impact that parties themselves and independently have on the competence reputations they hold.

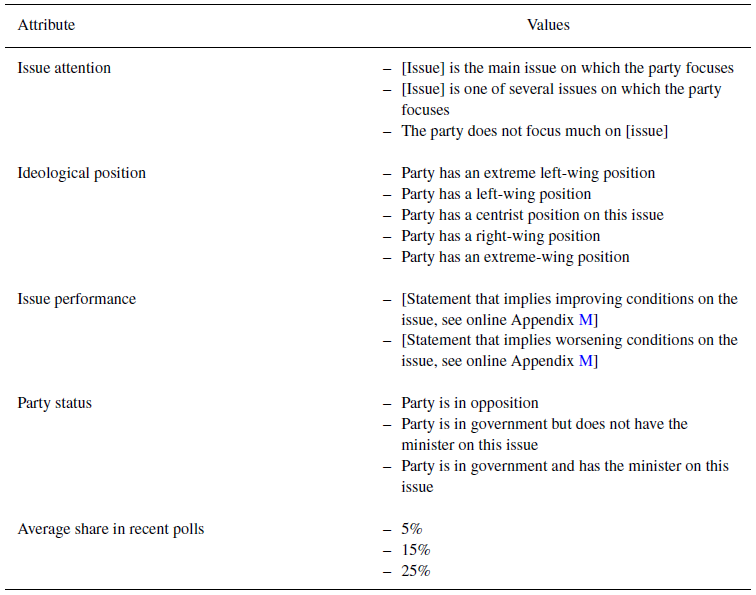

The party profiles included five different attributes, matching the variables that we considered in Study 1: parties’ attention to the issue, ideological position, issue performance, parties’ status as incumbent or opposition party and party size.Footnote 16 Table 4 provides an overview of the attributes and possible values, with information that is adapted to show the respondent's most important issue shown in brackets. Note that the values are not fully equivalent to the measures used in the observational study. For issue attention, for instance, we highlight whether the issue was the main issue for the party or not, which is not equivalent to a percentage of the manifesto that is devoted to an issue as in the models presented in Study 1. However, we opted to include statements that are straightforward to understand and that left little room for differences in interpretation by the respondents.Footnote 17 For the position of the parties, we include a statement on their general ideological position and no issue‐specific statements. As a result, the experiment cannot be compared to the issue‐specific analyses in Study 1.

Table 4. Overview of the conjoint study: attributes and values

The order of these attributes was randomised between respondents. In line with the observational analysis, we recoded the ideological position variable to indicate the extremity of the party, irrespective of the ideological side of the spectrum (i.e., centrist, left/right and extreme left/right). After seeing the party profiles, respondents were asked: ‘Below are some characteristics of two political parties. Which political party do you think is best to handle [issue]’? This question asking about which party is best at ‘handling’, ‘dealing with’ or ‘solving’ an issue is the standard measure of competence reputations in research on issue ownership (Seeberg, Reference Seeberg2017a). This dichotomous choice for one of the two parties is the dependent variable in the analyses.

We fielded our experiment in the Netherlands, a long‐standing and stable West‐European democracy, meaning that voters are used to expressing their political preferences and (dis)content freely. Furthermore, with its proportional electoral system and highly fragmented party system, voters are used to evaluating different indicators of different parties. Moreover, given the country's history of coalition governments, it was realistic to show them scenarios in which multiple parties governed in a coalition and in which specific parties (do not) hold certain ministerial portfolios. We fielded the experiment between 22 and 29 March 2023, immediately after the provincial and Senate elections in the Netherlands. This makes for a similar timing as the post‐electoral survey studies used in Study 1.

We collaborated with Bilendi to field the survey among a non‐probability sample consisting of online panellists. While the use of this type of non‐probability sample has been criticised, concerns about such samples do not prevent valid inference for experimental research (Coppock et al., Reference Coppock, Leeper and Mullinix Kevin2018). The survey included a quota to ensure that the sample would be representative for the Dutch population in terms of sex, age, educational attainment and region. In online Appendix N, we compare the demographics of the sample with population statistics, showing that our sample characteristics match the population well.Footnote 18 The experiment was fielded among 1600 respondents, and all respondents completed two choice tasks, resulting in sufficient statistical power (Orme, Reference Orme2010). In the analyses, we cluster the standard errors by the respondent. To analyse the conjoint experiment and in line with our pre‐registration plan, we graphically present the marginal means of the different values by attribute (Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020).

Results

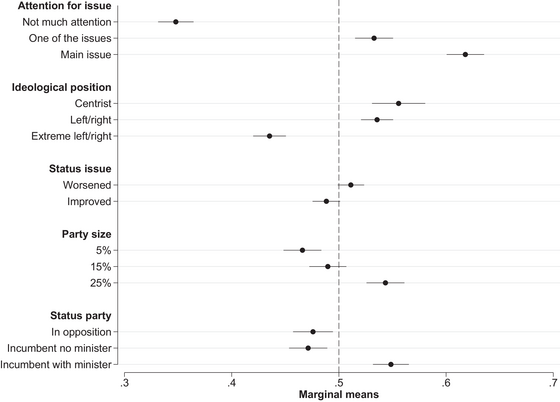

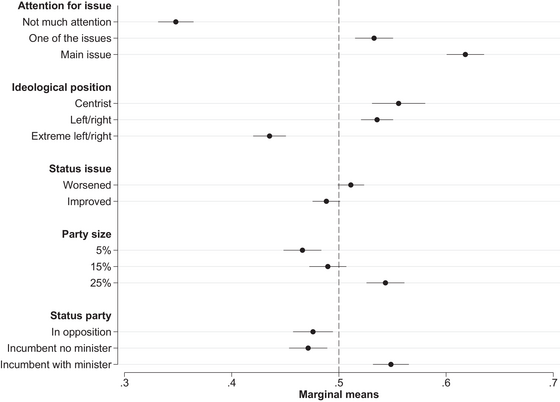

We start by examining the effects of each of the attributes on competence reputations. The marginal means in Figure 4 show, first, that issue attention is a strong determinant of perceived competence. For ideological positions, contrary to our expectation, respondents were less likely to choose the extreme party as the most competent party to handle an issue, while there is not much difference between a centrist and a leaning party. This result corroborates the findings from the observational study presented above regarding general left‐right ideology. Our findings are therefore in line with those of Johns and Kölln (Reference Johns and Kölln2020), who argue and show that centrist parties are, ceteris paribus, more likely to be considered competent.Footnote 19 While the experiment randomised positions, for real‐world parties it is also possible that there is some level of endogeneity between extremity and competence reputations, whereby parties with strong competence reputations on an issue take a position on the issue that is more popular – and which could be more centrist if that is where the median voter is located. Besides these theoretical reasons for finding that centrist parties are perceived to be more competent, it is also possible that a social desirability bias is at play, as respondents might be reluctant to favour parties that are explicitly labelled as extreme. Also for the issue status – that is, whether the conditions related to the issue improved or worsened – we find an effect that is opposite to what we hypothesised. The estimates in Figure 4 suggest that when conditions worsen, a party is somewhat (but not significantly) more likely to be selected than when conditions improve. Additional analyses, discussed below, indicate that these prompts were misunderstood by the respondents and caution should therefore be taken when interpreting these results. For party size, we find that larger parties are generally considered more competent in handling important issues. Finally, an incumbent party that has the minister on the issue is more likely to be selected as most competent.

Figure 4. Marginal means competence reputations.

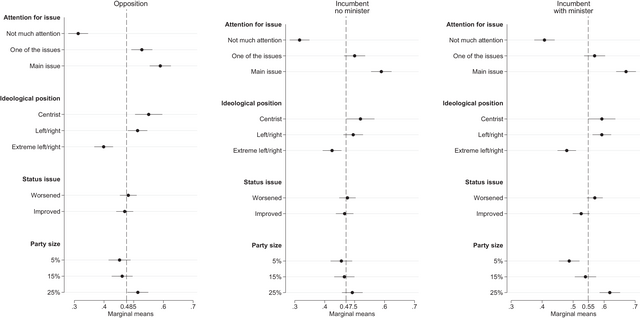

As in the observational analyses, we explore whether these patterns depend on the status of the party through a subgroup analysis. The results are displayed in Figure 5. Note that we adjust the baseline levels (i.e., the vertical dashed line shown on the x‐axis) for the different subgroups.

Figure 5. Marginal means competence reputations for subgroups.

The results are mostly in line with those in Figure 4, although they also show some heterogeneity between the subgroups, in line with the observational analyses. First, issue attention is an important determinant of competence reputations for all three groups, but the differences are more pronounced among opposition parties. For ideological positions, extreme parties are still less likely to be selected, although differences are somewhat less pronounced for incumbent parties. Issue status, which taps the role of performance, does not have a meaningful effect for any of the subgroups, while party size is mostly relevant for incumbent parties holding the ministerial portfolio.

Taken together, these results partially support the results of the observational analyses. In line with the first hypothesis, the conjoint results suggest that parties can build competence reputations when they have much attention for this issue, and this mechanism is strongest for opposition parties. Looking at the role of ideological position, we do not find support for the second hypothesis but find consistent evidence for the opposite association. For the third hypothesis, the experimental results contrast with those of the observational analyses: whereas the latter showed significant effects of unemployment rates on perceived competence, the experiment does not show significant effects of issue status. We have three speculative explanations for this null effect of competence. The first is the limited external validity of the experiments. The null effect of issue status could be caused by the hypothetical nature of the experiment. Informing respondents that the conditions related to an issue were improving or worsening might be too abstract to reproduce what happens when people live through and perceive the improving or worsening conditions themselves. Furthermore, whereas in real life the incumbent parties, and especially those holding the ministerial portfolio, would try to take credit for improving circumstances, this was reduced to a simple, factual statement in the experiment. A second possible explanation is that respondents might not have understood these prompts as factual statements regarding the issue status. Finally, the effect of competence might run through other variables such as party status and party size. We present exploratory analyses supporting these explanations below.

Additional tests

We also conducted a series of additional tests. First, besides the forced choice, we also asked respondents to rate each of the two presented parties on a competence‐scale ranging from 0 (not competent at all) to 10 (very competent). Replicating the models using the scores on this scale as the dependent variable, the results are mostly in line with those presented here (see online Appendix P).

We also asked respondents which party they would vote for if they would be confronted with the two respective party profiles in an election. We use this measure as an outcome variable in an exploratory test that was not pre‐registered. The results are reported in online Appendix Q and are fully in line with those presented here. Moreover, we replicated the analyses using only the data from the first conjoint task to verify whether the results were influenced by learning effects. The results in online Appendix R indicate that there are no carry‐over effects.

Third, we conducted subgroup analyses distinguishing respondents based on individual‐characteristics age, sex, educational level and ideological position. This analysis was not pre‐registered and is therefore exploratory. The results, in online Appendix S, show no substantial differences between these groups.

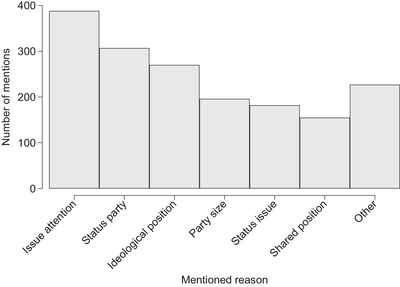

Finally, we included an open‐ended question in the survey, asking respondents why they opted for the one party over the other. We coded the responses to this question (asked two times to each respondent; following every choice) specifying whether the respondent noted one of the mechanisms under investigation or a residual category. Figure 6 displays the number of times that different reasons for a choice were mentioned. Because we coded the data on the level of stated reasons (a respondent could report several reasons for their choice), we reported absolute numbers instead of proportions.

Figure 6. Self‐reported reasons for the choice of issue owner.

The results in Figure 6 are mostly in line with those of the analyses above. The single most mentioned reason for the choice of the most competent party is that the party has a lot of attention for the issue – and the fact that a party does not have attention for an issue was also mentioned as the reason not to choose that party. In line with the results in Figure 4, respondents indicated in large numbers that they prefer a party in office, and with the minister, as such a party would be most likely to be able to make actual changes. Respondents note that ‘Governing can accomplish more than being on the sideline’ and that ‘a party can only make changes if they have the authority to make decisions’. For the same reason the size of the party – that is, its support base – was mentioned frequently, as respondents believed that larger parties would have more opportunities to push their agenda and views forward.

Besides the party being in a position to design policy, and in line with the results above, the general ideological position of the party mattered a great deal. While several respondents mentioned specific party positions (liking or disliking left or right parties generally, or not wanting to support an extreme party), the additional category ‘shared position’ refers to respondents who indicate that one of the parties shares their own views best – without clarifying what factor they based this consideration on.

While the conjoint results do not indicate a strong impact of the indicator of performance, that is, whether the status of the issue improved or worsened, competence arguments were mentioned a substantial number of times in the open‐ended questions. These results, and the data of this open question in general, shed new light on the results regarding competence. As discussed above, party status and party size are important determinants of competence reputations, as several respondents opted for the party with the minister because a party can only make a real difference in that position and because larger parties will be better able to push their agenda and competently handle issues. It is hence likely that issue competence does matter, but that its effect runs through other variables. Hence, while we do not find effects of the issue status specifically, some of the other attributes in the model seem to have signalled implied competence, and respondents took these signals into account. Furthermore, some respondents misinterpreted the performance promptly and took it for a statement made by a party. These respondents actually appreciated that the party acknowledges that a problem has worsened, and thought the party was more likely to tackle this issue in the future or criticised it for stating that the problem improved when they felt like it did not. Competence hence seemed to matter to some extent when respondents assessed different party profiles. Finally, there is the residual category, referring to respondents who felt like the one party seemed more fit to the task of handling the issue without further reflection or other reasons that were not attributable to one of the included prompts.

Taken together, these results further support the conclusions from the analyses above. Having sufficient attention for an issue is the most important determinant of parties’ competence reputations. However, parties also need to be in a position where they can make changes, by having a large support base and an executive position, increasing their perceived competence to handle issues. Furthermore, extremist parties are generally considered less fit to handle important issues. Besides these implications for our study specifically, the answers to this open question also suggest that many respondents did not understand the issue handling question as being about ‘issue competence’. Several respondents interpreted it as a question about a party's practical ability to get things done (e.g., by being in power or having some form of control over the issue), rather than about which party is the most competent to address the issue. As the question used in this experiment is the standard question to measure competence reputations or issue ownership, future research should examine respondents’ interpretation of it in more depth.

Conclusion

Issue ownership influences voting behaviour and parties are known to engage in strategies that increase the salience of the issues they own. While several earlier studies examined the individual‐level correlates of citizens’ perceptions of issue ownership (Craig & Cossette, Reference Craig and Cossette2020; Stubager & Slothuus, Reference Stubager and Slothuus2013), the party‐level sources of issue ownership perceptions have received less scholarly attention.

We contribute to this line of research by means of a large‐scale examination of the sources of parties’ competence reputations – the most‐often investigated dimension of issue ownership. Acknowledging the long‐term standing of competence perceptions, we focused on what parties can do in the shorter term, as these marginal changes can accumulate and in this way change parties’ reputation. Building on previous research (Egan, Reference Egan2013), we focused on three main aspects of party behaviour: their focus on specific issues in their electoral manifestos, the extremity of their ideological positions and their performance. We argued that parties should be considered more competent on issues when they emphasise them more, when they have a more extreme position on the issue and when they have a track record of good performance on the issue. We systematically examined whether there were indications of heterogeneity in these mechanisms between parties, based on their status as an incumbent or an opposition party and whether they hold the ministerial portfolio on an issue.

The results of the observational analyses provide suggestive evidence that each of the three mechanisms is associated with variation in competence reputations. Importantly, however, in each case, we find much heterogeneity between parties. The main determinant of perceived competence is attention to the issue in the party manifesto, and this mechanism is particularly strong for opposition parties. A similar finding arises from the analysis of extreme party positions: while generally parties seem to be punished for holding extreme positions, opposition parties seem to be able to gain from holding an extreme position on specific issues. For incumbent parties, performance matters most – and especially when they hold the ministerial portfolio in their party. Good performance allows them to gain a better competence reputation, that is lost by the opposition.

The results of the experimental analyses provide insights into the factors that respondents look for when presented with very clear and direct information. While this limits the experiment's external validity, it provides clear support for the strongest mechanisms. First, the results further emphasise the importance of issue attention for competence reputations, as they show that parties, regardless of their status as incumbent or opposition parties, gain perceived competence by displaying commitment to an issue. When it comes to extremity, the results further corroborate that extreme parties are less likely to be considered competent in handling important issues. Finally, while the competence prompt did not result in the expected effects, the answers to open questions provide suggestive evidence that people care about parties’ competence and their ability to make changes. Future research can test each of these separate mechanisms further, with more detailed prompts.

Our analysis is subject to some limitations. First, we are limited to measuring party positions on a small set of issues in the observational analyses, and we did not include issue‐specific positions in the experiments. It is likely that the wording of the prompt, describing the parties as ‘extreme’, made it less likely that respondents were willing to favour this party. For the observational analyses, we had to make use of whatever issues were measured in election surveys, and these issues could not always be straightforwardly connected to specific issue codes from The Manifesto Project or to indicators of performance. We opted to use strict criteria, but future research could combine different data sources – when available – and issue‐specific statements in an experimental context to expand the models.

Second, and related, the observational analyses only use one measure of party performance. The unemployment rate is a widely used measure in studies of performance voting, but there is no obvious connection with how parties in opposition performed. While it can be argued that a decline in unemployment rates is – at least in part – a result of decisions taken by parties in government, an increase in unemployment rates cannot be attributed to the actions of opposition parties. To address such limitations, we hope that future studies can further explore the uncovered mechanisms and the importance of performance, in particular, in more depth. We also conducted an additional analysis using an alternative measure of issue performance: the proportion of pledges about the issue that parties were able to fulfil during the last term (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). These analyses suffer from important data limitations but the results, reported in online Appendix T, do not show any effects of pledge fulfilment on competence reputations. With regard to the experiment, selecting the issues that are most important to the respondents has a disadvantage in that they are likely to have pre‐treatment perceptions of whether or not things are improving, possibly limiting the treatment effect of this attribute.

Third, our study makes abstraction of the context – both in terms of space and time – in which parties operate. While this fits our research aim focusing on party behaviour in general, future research could focus on the ways in which contextual factors condition the direct and moderating effects studied here. Specifically context‐related factors such as issue salience, the degree of competition on an issue and the type and contentiousness of an issue – for instance distinguishing valence from positional issues – are relevant factors to explore in future research.

Despite these shortcomings, we find that parties can indeed control to some extent their competence reputations on issues. While some characteristics such as the size of their support base might be out of parties’ control, they can signal their commitment to an issue by putting sufficient emphasis on this issue – and this holds especially for opposition parties. Furthermore, and in line with the central voter theorem, extreme parties are generally considered less competent.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Henrik Seeberg Bech Seeberg for making his data on issue ownership publicly available, and Elin Naurin, Terry Royed and Dominic Duval for sharing their data on pledge fulfilment in Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. We also thank the participants of the ECPR General Conference 2021, APSA Conference 2021, the Politicologenetmaal 2021 and a seminar of the Comparative Working Group at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for valuable feedback. Finally, we are grateful to Henrik Bech Seeberg and Stefaan Walgrave for commenting on a previous version of this paper.

Data availability statement

Replication data and code are available on Harvard's Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JYXPAS

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary Information