Ventenata dubia (ventenata) is an invasive species in Conservation Reserve Program sites, rangelands, and wildlands. Herbicides are an option for management of V. dubia and other annual weedy grasses in non-cropland and native landscapes. Current registered herbicides have little residual activity, require annual re-application, or are injurious to desirable vegetation. In the year of application, indaziflam controlled V. dubia greater than 80% when applied with glyphosate and greater than 90% when applied with rimsulfuron. At 1 yr after application, V. dubia control was greater than 90% when indaziflam was combined with glyphosate or rimsulfuron. Ventenata dubia seed viability in soil seedbanks is short, with only a small percentage remaining viable at 3 yr. Thus, sustained control from a single indaziflam application may facilitate long-term control, particularly with a PRE herbicide applied in year 3 that would further control remaining V. dubia germinating from the seedbank. In addition, perennial cover from Bromus inermis (smooth brome) or Pseudoroegneria spicata (bluebunch wheatgrass) increased by 30 percentage points when indaziflam was used with glyphosate, and 10 percentage points when used with rimsulfuron. Successful and sustained V. dubia control leading to perennial grass recovery provides further incentive to integrate indaziflam in combination with either glyphosate or rimsulfuron into a management regimen. Indaziflam appears to be a new tool to control V. dubia invasions while minimally impacting desired vegetation.

Introduction

Non-cropland areas of eastern Washington are a patchwork of diverse ecosystems, ranging from Palouse Prairie to rangeland to Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) areas (Looney and Eigenbrode Reference Looney and Eigenbrode2012). Palouse Prairie is one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America, existing as fragments scattered within production agriculture landscape (Looney and Eigenbrode Reference Looney and Eigenbrode2012), and CRP grassland is vital for preventing soil erosion resulting from wind and precipitation. The land occupied by non-crop vegetation, provided by prairie remnants and CRP, offers diversity in an agricultural matrix, wildlife habitat, insect refuges, and soil conservation (Looney and Eigenbrode Reference Looney and Eigenbrode2012). Prairie remnants, rangeland, and CRP often occupy adjacent land (Looney and Eigenbrode Reference Looney and Eigenbrode2012), potentially impacting one another by allowing points of entry and movement of weedy species like ventenata [Ventenata dubia (Leers) Coss].

Ventenata dubia, a winter annual grass, is a serious threat to isolated Palouse Prairie grasslands, CRP land, rangeland, and non-cropland areas in the inland Pacific Northwest (iPNW) (CABI 2018). First reported in 1952 in the iPNW, V. dubia negatively affects land productivity, wildlife habitat, and soil quality through increased soil erosion (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Pavek and Prather2015). Recent work indicates the range of V. dubia is expanding into vulnerable sagebrush steppe rangelands, and populations have now been identified in Oregon, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming (Dittel et al. Reference Dittel, Sanchez, Ellsworth, Morozumi and Mata-Gonzalez2018; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Norton and Prather2018). Ventenata dubia displaces existing vegetation through competition by developing dense litter that provides a moist environment for V. dubia seed germination in either fall or early spring before competing vegetation can establish or break dormancy (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Pavek and Prather2015). Ventenata dubia then competes with desirable species by using early spring soil moisture (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Pavek and Prather2015). The high silica content found in V. dubia reduces the litter decomposition rate and lowers the plant’s desirability as forage (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Pavek and Prather2015; Wolff Reference Wolff, Mealor, Collier, Miller and Burnett2013). Management of V. dubia is critical for preservation of remnant Palouse Prairie, CRP, rangeland, and non-crop areas in the iPNW.

Ventenata dubia management in Palouse Prairie, CRP grasslands, and rangeland requires herbicide options that do not injure established perennial grasses or other desirable native or coexisting vegetation. Failure to choose an effective herbicide or misapplication and mistiming, may lead to negative impacts on desirable vegetation or diminished weed management (Wallace and Prather Reference Wallace and Prather2016). Imazapic (Plateau®, BASF Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC), glyphosate (Roundup WeatherMax®, Monsanto Company, St. Louis, MO) and rimsulfuron (Matrix SG®, DuPont Crop Protection, Wilmington, DE) are commonly used for management of winter annual grass weeds in non-cropland (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, De and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b; Sheley et al. Reference Sheley, Carpinelli and Morghan2007). Herbicide application timing is vital to maximize the efficacy of herbicide treatments and minimize injury to non-target vegetation (Wallace and Prather Reference Wallace and Prather2016). Ventenata dubia management can be achieved using some of the aforementioned products, for example, control was 97% to 98% and 63% to 83% with rimsulfuron or imazapic, respectively, at 10 mo after PRE applications (Wallace and Prather Reference Wallace and Prather2016). However, neither rimsulfuron nor imazapic consistently control winter annual grasses for more than a single season (Mangold et al. Reference Mangold, Parkinson, Duncan, Rice, Davis and Menalled2013; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, De and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b; Sheley et al. Reference Sheley, Carpinelli and Morghan2007; Wallace and Prather Reference Wallace and Prather2016).

Herbicides that provide residual control of germinating seedlings without harming desirable perennials are needed. Indaziflam (Esplanade®, Bayer Crop Science, Research Triangle Park, NC is a cellulose biosynthesis inhibitor (CBI) labeled for use in turf, perennial crops, and, most recently, non-cropland as a PRE herbicide (Brabham et al. Reference Brabham, Lei, Gu, Stork, Barrett and DeBolt2014; Shaner Reference Shaner2014). When cellulose development is disrupted, initial roots cease to elongate and coleoptiles fail to emerge from the exocarp (Brabham et al. Reference Brabham, Lei, Gu, Stork, Barrett and DeBolt2014). Therefore, CBI herbicides have minimal impact on well-established perennial vegetation while providing control of emerging weed seedlings (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, De and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b, Reference Sebastian, Nissen, Sebastian, Meiman and Beck2017). Commonly, CBI herbicides are applied PRE, specifically targeting weed seeds as they germinate and resulting in inhibited seedling growth (Sabba and Vaughn Reference Sabba and Vaughn1999).

Dose–response studies conducted by Sebastian et al. (Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b) to compare indaziflam and imazapic demonstrated that indaziflam had increased activity on winter annual grasses compared with imazapic. Herbicide dose causing 50% dry biomass reduction (GD50) values indicate indaziflam controls V. dubia at a dose 16 times lower than imazapic. Differences in potency between indaziflam and imazapic are due to differences in modes of action, water solubility, and degradation by soil microbes (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b). As such, indaziflam controls winter annual grasses longer than imazapic (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, De and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b). Our hypothesis was that V. dubia would respond to treatments of indaziflam similar to downy brome (Bromus tectorum L.), and that such treatments would not injure perennial plant species. Therefore, the objective of this study was to quantify the response of a V. dubia–invaded CRP grassland community to an early-season application of indaziflam in comparison to herbicides typically used for invasive annual grass management.

Materials and Methods

Field trials were established in 2016 on CRP land near Pullman, WA (46°49′32.16″N, 117°13′1.46″W, Palouse silt loam [fine-silty, mixed, superactive, mesic Pachic Ultic Haploxerolls]), and Moscow, ID (46°46′26.67″N, 177°13′1.46″W, Joel silt loam [fine-silty, mixed, superactive, frigid Alfic Argixerolls]), on sites densely populated with V. dubia. Desirable perennial grass species included smooth brome [Bromus inermis Leyss] and bluebunch wheatgrass [Pseudoroegneria spicata (Pursh) Á. Löve] (25 to 30% cover) interspersed with intermediate wheatgrass [Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey] (5% cover). Plots at each location were 9 by 3 m with treatments arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications at Pullman and three replications at Moscow. Herbicide treatments (Table 1) were applied at the Pullman site on February 25, 2016 (61 cumulative growing degree days at base temperature 0 C, beginning January 1, 2016), while perennial grasses were assessed as dormant. Herbicide treatments were applied at the Moscow site March 21, 2016 (106 cumulative growing degree days at base 0 C), when V. dubia seedlings were at the 1-leaf stage. All herbicide treatments were applied with a nonionic surfactant at 0.25% v/v and delivered with a CO2 -pressurized backpack sprayer at a rate of 140 L ha−1 using TeeJet® 8002E flat-fan nozzles (TeeJet Technologies, Springfield, IL). Application conditions for each application are presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Herbicide treatments and rates tested for control of Ventenata dubia in Conservation Reserve Program land.

a All herbicide treatments included 0.25% v/v nonionic surfactant.

Table 2. Environmental conditions at the time of herbicide application for Pullman, WA, and Moscow, ID.

Herbicide efficacy was evaluated by visually estimating the average cover (%) for each species present within 0.1-m2 quadrats. Cover was assessed in two random sites for each treatment plot. Ventenata dubia cover was assessed at 3 mo after treatment (MAT) in Moscow and 6 MAT in Pullman in 2016, although in a Mediterranean climate assessment timing is not critical, as little new growth occurs during the summer. Cover assessments were repeated at 16 MAT at both sites to evaluate the reduction of V. dubia cover over time. Aboveground biomass samples were collected from both sites at 17 MAT. Aboveground biomass from two 0.1-m2 quadrats within each plot was harvested at ground level and separated by species at both sites. Samples were cut and sorted in situ and then oven-dried at 60 C for 1 wk.

Plant canopy cover data were arcsine square-root transformed and tested by ANOVA using PROC MIXED (SAS® v. 9.4, 2017, SAS Analytics and Software Solutions, Cary, NC), and means were separated using LSMEANS (P < 0.05, α = 0.1, 0.05). Transformation did not improve variance structure; results are therefore presented using nontransformed data. Herbicide treatment was considered a fixed effect. Year, location, year by location, replication by MAT by location, treatment by MAT, treatment by location, and treatment by MAT by location were considered random effects (McIntosh Reference McIntosh2015; Moore and Dixon Reference Moore and Dixon2015). Biomass data were analyzed similarly to cover data with the absence of year as a random factor. Species richness and diversity assessments were conducted to identify differences associated with herbicide treatments (Heip and Engels Reference Heip and Engels1974; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Caruso, Buscot, Fischer, Hancock, Maier, Meiners, Muller, Obermaier, Prati, Socher, Sonnemann, Waschke, Wubet, Wurst and Rillig2014; Spellerberg and Fedor Reference Spellerberg and Fedor2003; Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, Willis and Field2001). Species richness was expressed as the number of species within samples. Diversity was represented with Shannon’s and Simpson’s diversity indices averaged over species present at each site.

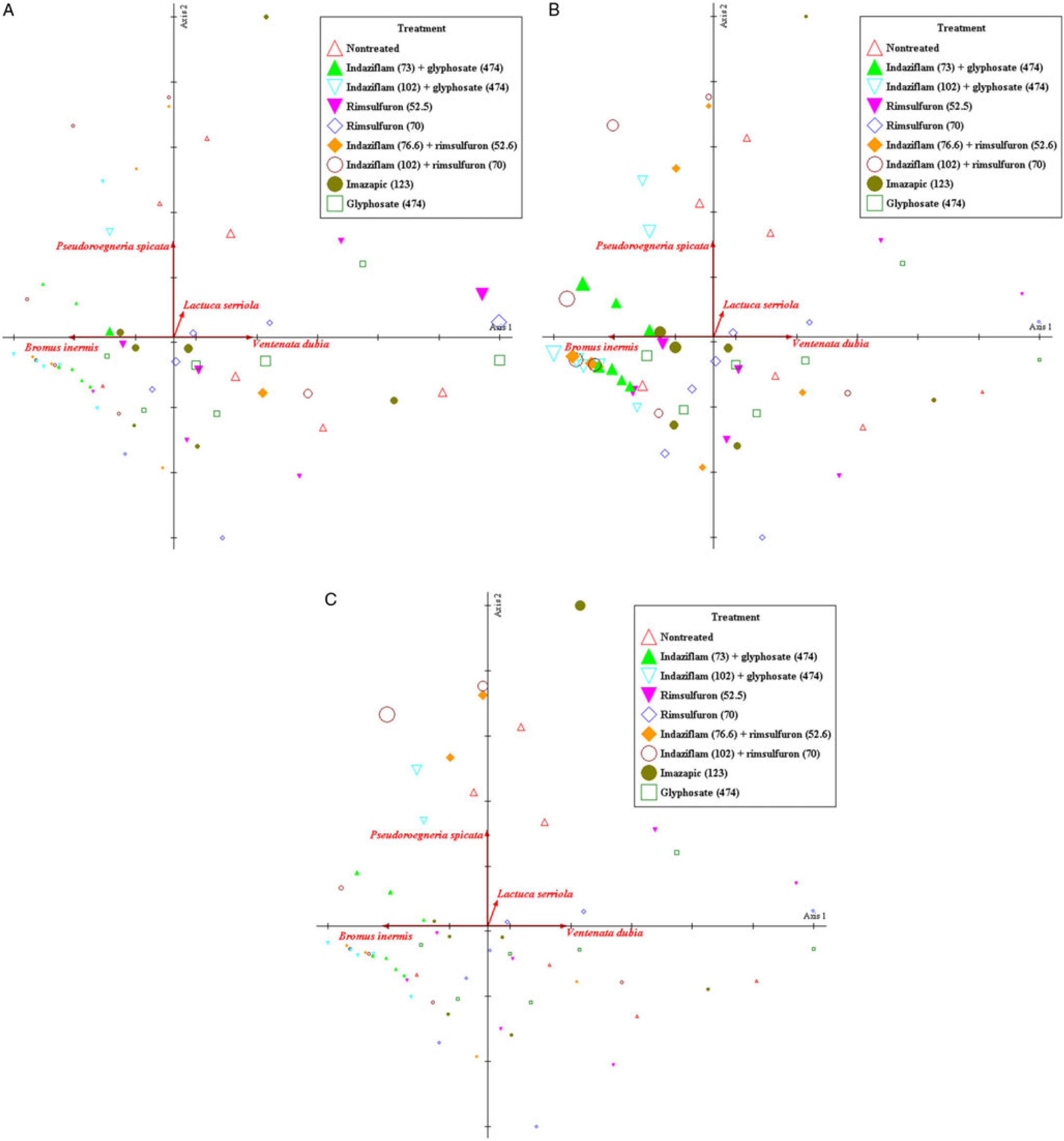

Biomass data were ordinated in two dimensions by nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMS). Species cover values by treatment and replication at 16 MAT were ordinated using NMS with the program PC-ORD v. 6.0 (McCune and Mefford Reference McCune and Mefford2011). The distance measure used was the Sørensen index, the number of runs with real data = 10, maximum number of iterations = 400 and number of randomized runs = 50. NMS runs were repeated 20 times with random starting configurations in one to seven dimensions, and the solution with the best balance of dimensionality and stress was chosen. In all ordinations, the first two dimensions provided the best balance between variance and stress reduction (stress was 13.36 in the final iteration, instability = 0.00). The previous ordination was rerun with dimensions limited to two. A varimax rotation was used to maximize the loadings of individual variables on the dimensions of the reduced ordination space (McCune and Mefford Reference McCune and Mefford2011). Total variance explained by the two axes was 0.943 (an r of 0.55 for axis 1, and an r of 0.392 for axis 2).

Results and Discussion

A significant interaction was observed between MAT and treatment (P = 0.0294) and MAT and location (P = 0.0361) for V. dubia and perennial grass cover. Therefore, cover data were analyzed separately and are presented by year and location. In 2016 at Moscow, all treatments except glyphosate applied alone reduced V. dubia cover compared with the nontreated at 3 MAT (Table 3). Ventenata dubia cover was 20% or less with all treatments except glyphosate alone. In 2016 at Pullman, V. dubia cover was 8% or less for all treatments except glyphosate alone, which was not different from the nontreated. At both locations, treatments containing indaziflam, rimsulfuron, or imazapic resulted in similar and significantly reduced V. dubia cover (Table 3). The lack of control when glyphosate was applied alone may be explained by litter providing a physical barrier between the herbicide and germinated but not emerged seedlings. A similar process was observed for medusahead [Taeniatherum caput-medusae (L.) Nevski] and litter (Kyser et al. Reference Kyser, Ditomaso, Doran, Orloff, Wilson, Lancaster, Lile and Porath2007). Alternately, V. dubia germination may have continued after the application of glyphosate, although germination is thought to occur in a limited time period (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Pavek and Prather2015). Finally, V. dubia may not have been actively growing during or after the application to the site near Pullman, WA. A POST-applied herbicide combined with a herbicide with residual activity like indaziflam appears to be an effective first-year treatment and gives managers increased flexibility, particularly when using rimsulfuron.

Table 3. Ventenata dubia and perennial grass cover at 3 mo after treatment in Moscow, ID, and 6 mo after treatment in Pullman, WA. a

a Moscow: applied March 21, 2016; evaluated in June 2016. Pullman: applied February 25, 2016; evaluated in August 2016.

b Dominant perennial grass species present at the site were smooth brome (Bromus inermis Leyss); bluebunch wheatgrass [Pseudoroegneria spicate (Pursh) Á. Löve]; along with interspersed intermediate wheatgrass [Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey] and tall wheatgrass [Thinopyrum ponticum (Podp.) Z.-W. Liu & R.-C. Wang].

c Means within the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at α = 0.05, except Pullman, where α = 0.1.

Ventanta dubia cover in 2017 (16 MAT) was reduced with indaziflam treatments when compared with the nontreated and rimsulfuron, glyphosate, and imazapic treatments at both Moscow and Pullman (P = 0.0100, Moscow; P < 0.0001, Pullman). In Moscow, V. dubia cover did not exceed 10% in treatments that included indaziflam. In Pullman, V. dubia was not observed in treatments that included indaziflam (Table 4). Indaziflam applied in mixture with glyphosate (73 g ai ha−1, 474 g ai ha−1; 102 g ai ha−1, 474 g ai ha−1) or rimsulfuron (76.6 g ai ha−1, 52.6 g ai ha−1; 102 g ai ha−1, 70 g ai ha−1) controlled V. dubia more than treatments with rimsulfuron or glyphosate alone. At the Pullman site, treatments that included indaziflam, regardless of rate, always had greater perennial grass cover than the nontreated. In Moscow, the perennial grass cover was greater with the lower rate of indaziflam, but was similar to the nontreated at the higher rate. Both V. dubia and perennial grass cover were more variable at the Moscow site, and thus few treatment effects were significant. Where V. dubia cover was less than the nontreated, perennial grass cover was usually increased (Table 4).

Table 4. Ventenata dubia and perennial grass cover in Moscow, ID, and Pullman, WA, in 2017, 16 mo after treatment. a

a Means within each column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at α = 0.05.

b Dominant perennial grass species present at the site were smooth brome (Bromus inermis Leyss); bluebunch wheatgrass [Pseudoroegneria spicate (Pursh) Á. Löve]; along with interspersed intermediate wheatgrass [Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey] and tall wheatgrass [Thinopyrum ponticum (Podp.) Z.-W. Liu & R.-C. Wang].

At 17 MAT, there was not a significant trial main effect for biomass (P = 0.1117). Therefore, biomass data were combined over the two trials (Table 5). Herbicide treatments without indaziflam had similar amounts of V. dubia biomass when compared with the nontreated (Table 5). Ventenata dubia biomass was reduced by treatments including indaziflam when compared with the nontreated and other herbicide treatments (P = 0.0253). Herbicide treatments including indaziflam contained <2 g m−2 of V. dubia compared with >42 g m−2 for other treatments, indicating V. dubia control exceeded 1 yr. As previously noted, rimsulfuron and imazapic do not typically control annual grass weeds for longer than a single season (Mangold et al. Reference Mangold, Parkinson, Duncan, Rice, Davis and Menalled2013; Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, De and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b; Sheley et al. Reference Sheley, Carpinelli and Morghan2007; Wallace and Prather Reference Wallace and Prather2016).

Table 5. Biomass of Ventenata dubia and perennial grass combined from sites in Moscow, ID, and Pullman, WA, in 2017, 17 mo after treatment. a

a Means within each column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at α = 0.05.

b Dominant perennial grass species present at the site were smooth brome (Bromus inermis Leyss); bluebunch wheatgrass [Pseudoroegneria spicate (Pursh) Á. Löve]; along with interspersed intermediate wheatgrass [Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey] and tall wheatgrass [Thinopyrum ponticum (Podp.) Z.-W. Liu & R.-C. Wang].

Perennial grasses benefited from successful residual control of V. dubia (Table 5). Perennial grass biomass was >250 g m−2 in treatments including indaziflam. In contrast, treatments of rimsulfuron or glyphosate alone had less perennial grass biomass (<150 g m−2) and were not different from the nontreated. These data suggest indaziflam controlled V. dubia, and there was no residual control from imazapic, rimsulfuron, or glyphosate when used alone, as assessed in the second year after application. Based on biomass assessments, perennial grasses appear to be released from competition when V. dubia is managed with indaziflam. The negative effects of V. dubia on perennial grass biomass production is significant and is likely related to the depletion of soil moisture before the perennial grasses begin to grow.

Ordination of plots from each trial site corroborated the univariate analyses (Figure 1A–C). Bromus inermis biomass was strongly associated with the reduction of V. dubia biomass; V. dubia was positively correlated on the horizontal axis (r = 0.777), while B. inermis had a strong negative correlation (r = −0.895) on the horizontal axis. Managing V. dubia had a positive effect on B. inermis biomass. Indaziflam treatments had a similar effect on P. spicata (r = 0.855), which was correlated with the vertical axis, and indaziflam treatment affected the position of P. spicata–dominated plots along the horizontal axis in the ordination space. Only a few plots had both species. Prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola L.) was also significantly correlated to the secondary axis (r = 0.458) and was found in all three plot types. Lactuca serriola is a common spring annual weed found in crop, CRP, and pasture and rangeland that usually appears after disturbance opens space for establishment, and it is considered an indicator of degraded sites. Overall, indaziflam reduced V. dubia biomass and increased perennial grass biomass.

Figure 1. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMS) plots with correlations between herbicide efficacy and Ventenata dubia biomass (A) and subsequent biomass of Bromus inermis (B), or Pseudoroegneria spicata (C). Vector directions indicate species association with the indicated direction in the ordination space, and increasing symbol size indicates increasing cover of each species.

The limited diversity present in the CRP study sites limits our ability to broadly assess potential impacts on diversity as a consequence of treatment by indaziflam. In our study, indaziflam plus rimsulfuron (76.6 + 52.6 g ai ha−1) had the highest richness score (Table 6), and reductions in species diversity indices are indicative of V. dubia removal. Treatments of indaziflam plus glyphosate (at rates of either 73 + 474 g ai ha−1 or 102 + 474 g ai ha−1) or indaziflam plus rimsulfuron (102 + 70 g ai ha−1) reduced species richness. However, the biomass data (Table 5) suggest these treatments had little impact on established perennial grasses. The reduction in species richness in these treatments indicates control of weedy species facilitates landscape improvement by opening space for reintroduction of desirable species. Further examination of indaziflam mixture effects on V. dubia and other weeds at sites with greater diversity is needed to evaluate herbicides in landscapes where management is inherently difficult. However, on degraded CRP sites like those evaluated in the present study, diversity is less critical and most reflective of the efficacy of a given treatment.

Table 6. Species richness and Shannon’s and Simpson’s diversity indices in relation to herbicide treatment. a

a When compared with the nontreated, reductions or additions to species diversity can be correlated with a reduction in Ventenata dubia or a reduction of other species.

In summary, results from our study indicate that indaziflam treatments effectively control V. dubia in CRP occupied by perennial grasses. Furthermore, these data indicate that indaziflam controlled V. dubia for more than 1 yr while minimally impacting desirable perennial vegetation. However, when used in early-season applications, indaziflam should be applied in mixture with herbicides that have POST activity to manage any emerged V. dubia. Potential V. dubia invasion into vulnerable habitats, such as sagebrush steppe rangeland in the Great Basin, is a major concern for landscapes damaged through the presence of other winter annual grass weeds (Sebastian et al. Reference Sebastian, Nissen, De and Rodrigues2016a, Reference Sebastian, Sebastian, Nissen and Beck2016b; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Norton and Prather2018). Land managers in states where V. dubia is being discovered can use this information and take proactive measures to minimize populations and prevent further spread, although additional information on the impact of indaziflam on desirable annual grass and broadleaf species is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bayer CropScience LP for partial funding of this research. This work was also supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch Project 1017286. No conflicts of interest have been declared.