1. Introduction

Three Four factors are particularly informative for lexical acquisition: the sociolinguistic context of language acquisition and use; word familiarity and the linguistic distance that shapes the quality of word representations (Newman & German, Reference Newman and German2002). Saiegh-Haddad & Haj, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018; Scarborough, Reference Scarborough2004; Sears et al., Reference Sears, Hino and Lupker1995); modality (Clark & Casillas, Reference Clark, Casillas and Allan2015; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Izumi, Reference Izumi2003; Reznick & Goldfield, Reference Reznick and Goldfield1992); and grammatical class (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017; Gentner, Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982; Kambanaros et al., Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann and Michaelides2013, Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann, Michaelides and Theodorou2014).

Arabic is a prototypical case of diglossia in which two varieties co-exist within the same speech community and serve distinct social and functional roles (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson1959; Hudson, Reference Hudson2002). Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is used in formal domains and in reading and writing, whereas Spoken Arabic (SpA; an umbrella term for regional vernaculars) is used for everyday communication (e.g., Albirini, Reference Albirini2016; Bassiouney, Reference Bassiouney2009; Brustad, Reference Brustad2000; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005, Reference Ryding2016; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014; Versteegh, Reference Versteegh2001). Variation in children’s exposure to MSA is associated with individual differences in receptive and productive MSA vocabulary (Al-Jarf, Reference Al-Jarf2006; Al-Shehri, Reference Al-Shehri2012; Aram et al., Reference Aram, Fine and Ziv2013a, Reference Aram, Korat, Saiegh-Haddad, Hassunha Arafat, Khoury and Abu Elhija2013b; Feitelson et al., Reference Feitelson, Goldstein, Iraqi and Share1993; Korat et al., Reference Korat, Shamir and Segal-Drori2014). The home literacy environment, the quality of parental literacy mediation, and the exposure to broadcast media in MSA (such as children’s television, widely circulated dubbed cartoons, news, and documentaries) also contribute to emergent literacy skills and MSA lexical knowledge (Albirini, Reference Albirini2016; Bassiouney, Reference Bassiouney2009; Korat et al., Reference Korat, Shamir and Segal-Drori2014; Ryding, Reference Ryding2016). In many Arab countries, a substantial share of children’s animated content is dubbed in MSA, providing early receptive exposure to MSA phonology and lexicon outside explicitly educational contexts. Studies on Arabic diglossia show that the linguistic distance between SpA and MSA affects language and literacy skills in MSA, including the quality of phonological representations in the lexicon, metalinguistic awareness, and word reading (for a review, see Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2023). Literacy skills in MSA are further predicted by language and literacy skills in SpA (Schiff & Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2018; Saiegh-Haddad & Schiff, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2025). Consistent with this, literacy interventions in kindergarten are more effective when they adopt a diglossia-centred approach – one that considers the linguistic distance between SpA and MSA and places the spoken variety at the centre of early literacy education (Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2023).

In a diglossic context, two phonological forms may be linked to the same meaning representation: a form used in the spoken variety and a form used in MSA. The phonological distance between these forms can vary along several parameters (e.g., phoneme substitution, deletion, and addition). The two forms may be completely different and unique to each variety (unique lexical items), partially overlapping (cognates), or identical (Saiegh-Haddad & Spolsky, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014). The acquisition of two lexicons therefore raises questions about factors that facilitate or inhibit lexical access and retrieval, and about how the two phonological forms are linked to, and contribute to, meaning representations. Saiegh-Haddad and Spolsky (Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014) report that words with overlapping phonological forms in Palestinian Arabic (PA) and MSA (i.e., cognates) constitute 40.6% of kindergarten children’s lexicons, identical words constitute 20.2%, and unique SpA words constitute 38.8%. Prior research shows that lexical-phonological distance between SpA and MSA predicts the quality of phonological representations in children’s lexicons (Saiegh-Haddad & Haj, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018), children’s phonological processing in working memory (Saiegh-Haddad & Ghawi-Dakwar, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Ghawi-Dakwar2017), and their phonological awareness (Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2003, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2004, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2007, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2019a, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Verhoeven and Perfetti2019b; Saiegh-Haddad et al., Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Levin, Hende and Ziv2011, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Shahbari-Kassem and Schiff2020; Schiff & Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2018). However, no study has examined the impact of linguistic distance on lexical acquisition in MSA, or the relationship between lexical knowledge in SpA and in MSA. There is also scant evidence on whether acquiring a word in one variety supports or inhibits the acquisition of its form and meaning in the other, particularly when the same meaning is associated with partially overlapping phonological forms (i.e., cognates).

Modality further conditions lexical knowledge in Arabic diglossia. SpA is used across both comprehension and production in everyday interaction, whereas MSA is disproportionately encountered in comprehension (listening/reading) and less in spontaneous production, aside from reading aloud and formal recitation (e.g., Qur’anic reading). For instance, Qur’an reading, at least among more literate speakers, involves articulation but may lack critical aspects of language production such as lexical selection and syntactic assembly. Thus, while MSA is mostly used for comprehension and SpA for both comprehension and production, the alignment of modality with variety is complex and context-dependent.

Grammatical class also bears on lexical acquisition. Nouns typically precede verbs because they are more concrete, imageable, and specific (Gentner, Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982). Khoury Aouad Saliby et al. (Reference Khoury Aouad Saliby, Dos Santos, Kouba Hreich and Messarra2017) tested Lebanese bilingual children with typical and atypical language development on noun and verb comprehension and production. They conducted cross-sectional group comparison using the Lebanese version of the Cross-linguistic Task (CLT-LB) for comprehension (picture recognition) and production (picture naming), targeting nouns and verbs separately. They found that both groups scored significantly higher on the noun lexical tasks. Similar noun advantages have been reported in monolingual and bilingual children (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017; Gentner, Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982; Kambanaros et al., Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann and Michaelides2013, Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann, Michaelides and Theodorou2014). Grammatical class also varies with respect to the degree of distance between SpA and MSA because many inflectional verb-related categories (e.g., person, number, gender, and mood) are realized differently across the two varieties (Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014). For instance, in MSA verbs inflect using prefixes and suffixes for person (1st, 2nd, and 3rd), number (singular, dual, and plural), and gender (masculine and feminine). Some of these distinctions are not marked in PA yielding smaller paradigms, e.g., dual number, as in /katab-a:/ “they two wrote,” is not marked on verbs at all in PA, instead the plural form /katab-u:/ is used. Verbs both perfective and imperfective are marked for mood (indicative, subjunctive, and jussive) as well which is not marked in PA. For example, ya-ktub-ū-na “they write” contrasts with PA yi-kitb-u, and the MSA subjunctive form marked as a final mood vowel (ʾan ya-ktub-a “to write”) is not marked in PA (y-ktub “to write”). MSA also preserves gender–number distinctions on the verb that PA neutralizes, e.g., al-banāt(u) ya-ktub-na “the girls write” (F.PL suffix – na) versus PA l-banāt b-y-ktb-u “the girls are writing” (general plural – u). By contrast, nouns in both varieties mark number, gender, and definiteness (MSA al-, PA il−/l-) and use both concatenative (sound) and non-concatenative (broken) plurals (e.g., kitāb ~ kutub “book ~ books”; muʿallima ~ muʿallimāt “female teacher ~ female teachers”), but MSA adds overt case not present in PA: MSA al-kalb-a “the dog-ACC,” al-kalb-i “dog-GEN,” al-kalb-u “the dog-NOM” versus PA il-kalb “the dog” for all cases. Consequently, in PA the bulk of morphology that is unique to MSA resides in verbal inflection (≈81% of all non-identical morphemes as reported in Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023), and MSA inflectional morphology continues to challenge learners from childhood through adolescence (Shahbari-Kassem et al., Reference Shahbari-Kassem, Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2025). These examples make visible why verbs carry greater cross-variety distance than nouns and why MSA items – especially verbs – impose higher morphological load than their PA counterparts. The current study investigates how lexical-phonological distance, modality, and grammatical class shape lexical knowledge in Arabic diglossia, and examines cross-lectal relationships between lexical knowledge in SpA (PA) and MSA.

1.1. Linguistic and functional factors in lexical knowledge

Lexical knowledge is affected by linguistic, or structural, and sociolinguistic-functional factors. According to the Lexical Restructuring Model (LRM: Metsala & Walley, Reference Metsala and Walley1998), as children’s vocabularies increase, the pressure for more accurate segmental representation increases, and lexical representations are restructured and become more accurate (Metsala, Reference Metsala1997). In turn, high-frequency and familiar words receive more pressure for restructuring than low-frequency and unfamiliar words. By the same token, early acquired words and words that are actively used by speakers would be more accurately represented and easier to retrieve than words that are acquired later in age and which are used for a limited set of communicative functions.

Lexical knowledge is also affected by modality. It is well documented that comprehension of words emerges before their production (Clark & Casillas, Reference Clark, Casillas and Allan2015; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Izumi, Reference Izumi2003; Reznick & Goldfield, Reference Reznick and Goldfield1992). According to the Output Hypothesis (Swain, Reference Swain1993), production requires the learner to move from “semantic processing” dominant in comprehension to more “syntactic processing” (Izumi, Reference Izumi2003) that is necessary for language production. The complexity of production of speech as compared to comprehension is also attributed to production being more demanding especially in terms of long-term memory and lexical retrieval than comprehension (Clark & Casillas, Reference Clark, Casillas and Allan2015; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Izumi, Reference Izumi2003; Reznick & Goldfield, Reference Reznick and Goldfield1992). In turn, the developmental gap between nouns and verbs in favour of nouns (discussed later) is expected to be more apparent in production, since verbs are loaded with more syntactic information, especially in Semitic languages like Arabic, as more derivational and inflectional complexity is involved in their formation (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Shahbari-Kassem et al., Reference Shahbari-Kassem, Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2025; Shamsan, Reference Shamsan2005).

Lexical knowledge is also affected by grammatical class, or lexical category: nouns versus verbs. The advantage of nouns over verbs in comprehension and production is argued to be a shared finding across languages, regardless of the nature of the language: highly inflected like Greek or minimally inflected like English (Gentner, Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982; Kambanaros et al., Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann, Michaelides and Theodorou2014), and in monolingual and bilingual children alike. For example, Altman et al. (Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017) tested 5- and 6-year-old monolingual and bilingual Russian–Hebrew children and found better performance on nouns over verbs in both groups. Kambanaros et al. (Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann and Michaelides2013) report similar results in bilectal (or diglossic) contexts, showing a noun advantage over verbs for typically developing bilectal children ages 3 to 6-year-old. It has been argued that nouns predate verbs because they are “more concrete, meaningful, imageable, specific and unambiguous than verbs” (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017, p. 4).

In Semitic Arabic, another explanation is viable and it pertains to the morphology of Arabic as a Semitic language with a rich inflectional and derivational structure particularly in the formation of verbs as compared to noun (Ravid, Reference Ravid and Lieber2019; Shamsan, Reference Shamsan2005). Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad (Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023) measured the distance in morphological structure between MSA and a local dialect of PA and showed a larger distance in inflectional than in derivational morphology. A detailed mapping of the morphological distance in inflectional and in derivational morphology showed that most of the morphemes used in PA were non-identical and the majority of these non-identical morphemes (64%) were in verb inflections. They also found that noun inflections were the least distant (either identical or strongly overlapping), whereas verb inflections were the most distant making up 81% of the structures in the most distant “unique” category. For instance, Arabic verbs agree with the subject in number and gender, and they change their surface form depending on person and mood. This means that the same verb acquires different inflectional forms, and this might make it more difficult for children to acquire the verbal system. In contrast with verbs, nouns are less morphologically varied; they code number and gender differences (as well as case in MSA) making them less varied. In addition, all Arabic verbs are morphologically derivationally complex encoding a root and a word pattern. In contrast, many nouns (~43%) are primitive (Shalhoub-Awwad & Joubran-Awadie, Reference Shalhoub-Awwad and Joubran-Awadie2021) and do not encode roots and patterns making them morphologically simpler (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014). If we assume that at least part of the learning of the morphology of nouns and verbs comes from exposure to MSA via storybook reading and the media, as well as from exposure to the ambient Spoken Arabic language variety, these findings imply that the morphological distance between MSA and PA in verb inflectional morphology makes the learning of verbs even more difficult given the morphological variability that inheres in this system as well as its even richer structure in MSA (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985; Gentner, Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982; Pinker, Reference Pinker2009).

In diglossia, differences between words in grammatical class might interact with modality. In Arabic diglossia, speakers of the language hear MSA (mainly, in the media) more than they actively use it for speech. As a result, MSA word representations are used mostly passively in comprehension whereas SpA words are used in both modalities: comprehension and production. This might result in a larger discrepancy between comprehension and production of words, as noted above, and especially for verbs, which encode more morpho-syntactic information than nouns and reveal a larger gap in morpho-syntactic structure in SpA versus MSA. Differences in use between the two varieties are sociolinguistic and functional in nature, yet they also imply differences in familiarity and experience and, in turn, differences in quality of lexical representations with consequences for comprehension and production.

Finally, neighbourhood density also contributes to the quality of lexical representations (Perfetti, Reference Perfetti2007). Newman and German (Reference Newman and German2002), found that neighbourhood density contributed to lexical knowledge in children aged 7–12 besides age-of-acquisition and word frequency. Neighbourhood density was also found to have a negative effect on naming in the presence of high-frequency neighbours (Luce, Reference Luce1986; Sears et al., Reference Sears, Hino and Lupker1995). As such, a word’s unambiguousness seems to derive from the statistical likelihood that it will be chosen from among other possible options of words, depending on both lexical frequency and the set of similarly sounding competing words. In line with this argument, Scarborough (Reference Scarborough2004) found that words with low relative frequencies receive much more competition from their neighbours, and so lexical access for these words is relatively more “lexically confusable” (p. 6). While information on spoken word frequency and neighbourhood density is not available for the various dialects of SpA including PA, the diglossic situation likely yields many words that have similar phonological forms in SpA and MSA, that is cognates, and in turn might yield a similar competition impact in children’s lexicon. Saiegh-Haddad and Spolsky (Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014) report that among PA-speaking kindergarten children, 40.6% of the words in their lexicons are cognates with partially overlapping forms in PA and MSA. Moreover, 42% of them are different by just one phonological distance parameter, such as phoneme substitution, deletion, or addition (e.g., PA /ðahab/ versus MSA /dahab/ “gold”), whereas 24% are different by two parameters, that is cognates, and, in turn, might yield a similar competition impact in children’s lexicon. For instance, Saiegh-Haddad and Spolsky (Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014) report that among children, almost 40% of the words in the lexicons of speakers of PA consist of cognates with partially overlapping forms in PA and MSA (e.g., PA /sama/ versus MSA /sama:ʕ/ “sky”).

1.2. The lexicon and lexical skills in Arabic diglossia

Arabic-speaking children across the Arabic-speaking regions grow up in diglossia. Hence, they acquire two linguistic systems: one in SpA, the language variety they use actively for everyday communication, and another in MSA, the language they hear on TV, in prayers, and in storybook reading, and later the language of literacy and education. The spoken variety is acquired naturally from the ambient language as early as the first day of life, and this variety continues to be used by all speakers for all oral language speech functions. When they reach school age, children start learning MSA as the language of literacy and of all the books they use. This variety alternates with SpA, however, even within the classroom, as the language of informal oral interactions (Amara, Reference Amara1995; Coulmas, Reference Coulmas1987). It is noteworthy that for Arabic speakers living in exile, children may have very limited exposure to MSA and may not eventually develop knowledge of this variety, or some may acquire some MSA knowledge only for prayers, but not SpA (Abdulkafi & Benmamoun, Reference Abdulkafi, Benmamoun, Saiegh-Haddad, Laks and McBride2022).

MSA is different from the spoken vernaculars across all language domains: phonologically, morphologically, syntactically, and lexically. “Paired lexical items” (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson1959), or shared words, constitute around 60% of the lexicon of young children (Saiegh-Haddad & Spolsky, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014). Yet, importantly, shared words can have identical forms in MSA and SpA, or they can be only partially overlapping (cognates) with critical consequences for representation and processing (Ghawi-Dakwar & Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Ghawi-Dakwar and Saiegh-Haddad2025; Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2003; Saiegh-Haddad & Ghawi-Dakwar, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Ghawi-Dakwar2017; Saiegh-Haddad & Haj, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018). Saiegh-Haddad and Spolsky (Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014) analysed the lexicon of monolingual 5-year-old speakers of PA, the SpA vernacular used by the Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel. They found that only 21.2% of the words in the lexicon of children had an identical phonological forms in the two varieties (e.g., PA /Ɂmi:r/ prince, /na:m/ sleep), while 38.2% were cognate words with partially overlapping phonological forms in the two varieties (e.g., PA /dahab /, MSA / ðahab / gold; PA /wiɁiʕ/, MSA/waqaɁ/ fall), and 40.6% were unique PA words not used in MSA at all (e.g., PA /ʃanta/, MSA /ħaqiːba/ a bag; PA /natt/, MSA /qafaz/ jump). Asli-Badarneh et al. (Reference Asli-Badarneh, Hipfner-Boucher, Bumgardner, AlJanaideh and Saiegh Haddad2023) investigated the composition of the lexicon used by Arabic-speaking immigrant in Canada (Age-range 7–12) as reflected in the narratives they produced orally. Though the task was administered at school and the instructions were given in MSA, over half of the Arabic lexicon used in their narratives consisted of words within their SpA vernacular: 21.55% identical words, 25.73% cognates in SpA form, and 12.18% unique SpA words.

The linguistic distance between SpA and MSA has been shown to challenge MSA language and literacy development with higher scores for MSA structures that keep an identical form in SpA as against cognate and unique MSA structures. This was demonstrated for phonological processing in working memory, phonological awareness, morphological awareness, and word decoding accuracy and fluency (for a review, Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2023). As for the effect of the linguistic distance on lexical-phonological representations in the mental lexicon, Saiegh-Haddad and Haj (Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018) used a receptive phonological accuracy judgement task to test the impact of the lexical-phonological distance on the quality of lexical-phonological representations comparing the accuracy judgements of identical, cognate, and unique MSA words undergoing phonological substitution among kindergarten, first grade, second grade, and sixth grade children. The results showed that identical words yielded the highest accuracy scores followed by cognate and then by unique MSA words across all tested grades. These results imply that differences between words in distance predict differences in quality of the underlying lexical representations. This is expected, in turn, to affect phonological processing in working memory (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley2003). Saiegh-Haddad and Ghawi-Dakwar (Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Ghawi-Dakwar2017) tested the effect of the phonological distance on phonological processing in memory using a non-word repetition task that manipulated distance and compared the repetition of pseudo-words encoding PA phonemes versus those encoding a single MSA phoneme each. The study showed a negative effect of distance on repetition with lower accuracy for pseudo-words encoding MSA phonemes both in kindergarten and in the first grade demonstrating long-term representational quality effects on phonological processing in working memory (Saiegh-Haddad et al., Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Levin, Hende and Ziv2011).

Word knowledge requires the establishment of phonological and semantic representations, as well as the creation of links between phonological and semantic representations. When the phonological representation is hard to establish, because it is novel and not within the spoken variety of children, lexical acquisition is harder. Ghawi-Dakwar and Saiegh-Haddad (Reference Ghawi-Dakwar and Saiegh-Haddad2025) tested this question in an experimental design in which the learning of pseudo-words was tested. The study compared word learning for pseudo-words encoding phonological structures within PA versus novel pseudo-word encoding one unique MSA phoneme each. The study showed that word learning of novel pseudo-words was harder than that of pseudo-words encoding PA phonological structures only, and this was true in both comprehension and production modalities as well as in kindergarten and in the first grade. Moreover, the study showed that kindergarten children found novel word learning in the production modality particularly more difficult with floor levels of performance. These results from an experimental word learning task imply that the lexical-phonological distance may be a constraint on lexical acquisition in Arabic diglossia. Similarly, bilingual research has demonstrated what is called “a cognate facilitation effect,” namely, that bilinguals recognize and produce cognates faster than non-cognates (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Chen and Geva2019; Ibrahim, Reference Ibrahim2006; Koda, Reference Koda, Koda and Zehler2008). This research has also demonstrated that the selection of one out of two lexical representations that have both semantic and phonological similarities may result in substitution errors (Sherkina, Reference Sherkina2003). The evidence for a cognate effect in bilinguals is mixed (De Groot, Reference De Groot2011) with some studies reporting the non-existence of a cognate effect. For example, Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Caramazza and Sebastian-Galles2005) reported that cognate benefits may manifest in subtler ways in tasks that do not directly measure lexical retrieval. Dijkstra et al. (Reference Dijkstra, Miwa, Brummelhuis, Sappelli and Baayen2010) noted that phonological mismatches could bring down the cognate benefit as they make cognates less common because cognates need to be cross-linguistically similar. The cognitive effort of controlling two languages in bilinguals has also been suggested to reduce the cognate advantage (Kroll & Bialystok, Reference Kroll and Bialystok2013). It might also be the case that, due to the overlap of cognates, implicit support is provided which is difficult to measure in explicit tasks since automaticity may obscure performance differences (Kroll & Bialystok, Reference Kroll and Bialystok2013). Additionally, De Groot (Reference De Groot2011) argues that the way bilinguals use their languages can already change cognate effect (and particularly, language dominance and proficiency). In sum, the effect of cognates is inconclusive reflecting frequency, language distance, and language dominance, as well as the balance between competition and support. It is noteworthy that in the bilingual literature, the term “cognate” refers to the same word with an identical representation in the two languages of bilinguals (these are akin to what Saiegh-Haddad and Spolsky [Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014] refer to as “identical” words in the case of Arabic diglossia). Cognate words in Arabic are akin to so-called partial cognates in the bilingual literature. In the context of Arabic diglossia, it is reasonable to argue that when an MSA word is identical in SpA (complete overlap in form), it will be easier for children to acquire, whereas an MSA word that is a cognate (overlaps only partially in form) will be more difficult given that the majority of the cognates are very similar in form (~70%) and might hence compete strongly for selection, and unique MSA words the most difficult. Moreover, these effects of linguistic distance might interact with modality and be more apparent in productive than in receptive tasks (Amara, Reference Amara1995; Coulmas, Reference Coulmas1987), and with grammatical class with this effect being more prominent in the acquisition of verbs than of nouns (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Shahbari-Kassem et al., Reference Shahbari-Kassem, Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2025; Shamsan, Reference Shamsan2005).

Despite the negative effect of linguistic distance, research has also demonstrated cross-language interdependence and transfer of skills between SpA and MSA (Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2023, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2025; Zamlut, Reference Zamlut2011). For instance, Saiegh-Haddad (Reference Saiegh-Haddad2018) tested phonological and morphological awareness in PA and in MSA and found cross-lectal relationship between skills in the two varieties. Specifically, metalinguistic phonological and morphological awareness skills in PA predicted word reading accuracy and fluency in MSA. Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff (Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2025) showed that reading comprehension in MSA was predicted by language and literacy skills in SpA, including SpA vocabulary knowledge, morphological awareness in SpA, and the decoding of identical SpA words. Finally, Haj et al. (Reference Haj, Saiegh-Haddad, Ghawi-Dakwar and Schiff2025) show that lexical skills in MSA (vocabulary knowledge and lexical representations) are grounded in the same skills in SpA demonstrating the interdependence between the two varieties. These results align with the linguistic interdependence hypothesis (Cummins, Reference Cummins1979) and are akin to those observed in bilingual and second-language learners (Alsherhi, Reference Alsherhi2021; August & Shanahan, Reference August and Shanahan2006; Chung et al., Reference Chung, Chen and Geva2019; Ringbom, Reference Ringbom and Rosa Alonso2016).

1.3. The current study

Given the effects of linguistic distance on children’s language and literacy skills acquisition (Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2023), the study of the impact of lexico-phonological distance on children’s lexical knowledge is warranted. Other relevant questions pertain to the role of modality (comprehension versus production) and grammatical class (nouns versus verbs) in lexical acquisition in Arabic and the interaction of these factors with linguistic distance. These factors are informative given the fact that modality and variety often align, with MSA used more for comprehension than production. Moreover, grammatical class, verbs more than nouns, yields different degrees of distance between SpA and MSA, and they are often morphologically more complex in MSA than in SpA. Every Arabic verb may be inflected to mark six morphological categories – number, person, gender, voice, tense, and mood. Yet, the essential meaning of the inflected verbs is retained (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014). These affixes are added to the stem mostly by a concatenative (linear) process to mark number, person, gender, voice, and mood, while a non-concatenative (nonlinear) process is formed to mark tense (Ryding, Reference Ryding2005). However, children may not fully acquire certain aspects of person, gender, and number agreements even after reaching the age of 6 years (Taha et al., Reference Taha, Stojanovik and Pagnamenta2021). Scant studies on the acquisition of verb inflection addressed the morphological distance between the spoken varieties and MSA (however, see Shahbari-Kassem et al., Reference Shahbari-Kassem, Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2025).

The current study addresses the role of modality, grammatical class, and linguistic distance in PA-speaking children’s lexical knowledge, as well as the relationship between lexical knowledge in SpA and MSA. The study addresses two research questions:

-

(a) What impacts lexical knowledge in PA and in MSA?

-

(b) Does lexical knowledge in PA contribute to lexical knowledge in MSA?

It is hypothesized that modality (comprehension versus production) and grammatical class (nouns versus verbs) will impact the children’s lexical knowledge in PA and in MSA; hence comprehension is expected to be higher than production, especially for verbs, and nouns are expected to yield higher scores than verbs. Lexical and lexico-phonological distance (comparing identical, cognate, and unique words) is expected to impact the participants’ MSA lexical knowledge especially in production; hence, identical words are expected to yield the highest accuracy rates, followed by cognates and then by unique words. Finally, it is also hypothesized that lexical knowledge in PA will scaffold lexical knowledge in MSA.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample of the study consisted of 30 (21 females) typically developing children, aged 65–78 months (mean age 5:9), attending public Arab kindergartens in the northern district in Israel. All children were monolingual who came from Arab villages and towns and were reported by parents to have typical language development with no past or present hearing difficulties. The study had institutional IRB approval (dated 18.01.2018) and was further approved by the Ministry of Education chief scientist (No. 11897). Due to COVID-19 restrictions, a computerized parental consent was obtained from all children’s parents via Google form.

To verify typical language development, all children were screened with a PA adaptation (Saiegh-Haddad & Ghawi-Dakwar, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Ghawi-Dakwar2017) of the Arabic language: Evaluation of Function (ALEF), a language testing battery created with a normative sample of 3- to 9-year-old Saudi Arabian children (Kornilov et al., Reference Kornilov, Rakhlin, Aljughaiman and Grigorenko2016). Ravens matrices (Kornilov et al., Reference Kornilov, Rakhlin, Aljughaiman and Grigorenko2016) were used to test for cognitive development. Children performed within the norm on all tasks. (See Appendix A – for more information on ALEF and scores for all screening tasks items, https://osf.io/wuk5n/files/osfstorage.)

2.2. Experimental tasks

Two experimental lexical tasks were designed for this study: one for PA: PA Cross-linguistic Lexical Task (PA-CLT) modelled after the CLT (Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015), and one for MSA: MSA Diglossic Lexical Task (MSA-DigLT), capturing the linguistic distance between PA and MSA. These two tasks were part of a larger battery developed within an Israel Science Foundation grant (ISF 454/18) awarded to the second and third authors. These tasks offer a detailed framework for studying lexical knowledge in Arabic diglossia targeting comprehension and production. The tasks aim to distinguish the cognitive processes involved in each modality and to investigate the impact of linguistic properties, particularly grammatical class and lexical-phonological distance on these processes. The comprehension tasks are picture selection tasks. They are designed to assess comprehension testing the participants’ ability to recognize and understand a lexical item in PA and in MSA. Participants see a series of prompts, each containing a target word and three distractors. Participants are instructed to select an image that corresponds to the target word. This comprehension task relies primarily on the participants’ receptive language, as children are required to map phonological forms to a semantic representation, and it does not involve language production. On the other hand, the production tasks are picture naming tasks. They require the participants to produce the target lexical items by viewing the images. The prompt for the production task is a single image. After showing the target image, participants are asked to name the object or action in the image. This task activates productive language skills since it requires not only recalling the meaning of the target item but also the meaning, sound, and structure necessary to produce the right spoken word. The differences in task requirements are expected to influence modality effects, with comprehension typically yielding higher accuracy rates than production. This is consistent with the Output Hypothesis, which posits that production tasks are inherently more demanding due to the need for syntactic processing and the integration of multiple linguistic components (Swain, Reference Swain1993). The increased cognitive load associated with production tasks may result in greater variability in performance, particularly for items with greater lexical-phonological distance or those belonging to more complex grammatical classes, verbs in our tasks. By clearly delineating the methodology for both comprehension and production tasks, this study aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing lexical knowledge in Arabic diglossia. The insights gained from this comparison will contribute to a deeper understanding of modality effects and their interaction with linguistic variables.

PA cross-linguistic lexical task (PA-CLT). The PA-CLT targets children’s receptive and productive knowledge of nouns and verbs in PA. The task was developed based on the principles outlined in Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015), and includes two sub-tasks that vary in modality: picture selection (comprehension) and picture naming (production), as well as an equal number of nouns and verbs (N = 30 per grammatical class per modality). Images presenting the target lexical items were selected from the original CLT pool of images (Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015), based on cultural adequacy. Our lexical items were selected from 165 nouns and 142 verbs that were tested for Age of Acquisition (AoA) using subjective judgements by 50 adult speakers of the same PA dialects (M age = 36.9 years) (Bashir et al., Reference Bashir, Armon-Lotem and Saiegh-Haddadforthcoming). AoA ranks were used to match items and distractors.

Since PA dialects do not always use an identical label for each concept, an additional constraint was added to the design outlined in Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015). Namely, only target lexical items that had an identical lexical representation and complexity (syllabic length and clusterhood) across the five examined local dialects of PA used in the north of Israel were targeted: Abu-Sinan, Sakhnin, Nazareth, Kufor Kanna, and Wadi Sallami (Bashir et al., Reference Bashir, Armon-Lotem and Saiegh-Haddadforthcoming). Also included were a small number of lexical items that were only slightly different in the different dialects, yet identical in terms of syllabic length and clusterhood (e.g., the word for glasses has different lexical representations in the different dialects: /na dˤara/, /na ðˤara/, /na dˤarat/, and /na ðˤarat/). Accordingly, in the comprehension task, the researcher provided the lexical representation that fit the specific dialect of each child. Similarly, in the production task, lexical representations according to the specific dialect were accepted. This deviation from MSA design procedure as described in Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015) was necessary considering the dialectal nature of PA and the goals of the current study. Furthermore, given the large variation in PA and MSA and the goals of the current study, where two tasks were developed, the PA-CLT was not designed fully in the accordance with the standard design procedure as described in Haman et al. (Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015). Specifically, following Haman 2015 a semantic distractor, which could serve as the target word for the production task, was selected first making sure it was taken from the same semantic category and matched for their Complexity Index (CI) and AoA values. However, unlike Haman, one of the other two distractors was visual (when possible) while the other was unrelated. The choice of a visual distractor was based on the need to keep a relation which is non-semantic, between the third distractor and the target.

In the comprehension picture selection task, three distractors were used per each noun and verb: (a) a semantically/categorically related (e.g., an elephant–a mouse; eat–lick) or an associatively related (e.g., a bicycle–a helmet; whisper–listen) distractor, (b) a visual distractor (e.g., a door–a blackboard; eat–drink), and an unrelated distractor (e.g., a tree–a fish; sleep–drive). Each target lexical item and the three distractors were matched on CI: (syllabic length: 1–3 syllables and consonant clusterhood/sequencing: +\- cluster) and on subjective AoA. For example, the target item, /zerr/ “button,” was presented with a semantic distractor, /ʔʃatˤtˤ/ “belt,” a visual distractor, /ʕuʃʃ /“nest,” and an unrelated distractor, /fardd/ “gun.” In this example, the target lexical item and the three distractors were all monosyllabic, featuring a consonant cluster (+cluster), and they were reportedly acquired around the same age (AoA = 3.3 years old). An additional example from the verbs in PA-CLT is the target verb /ʕasˤar/ “squeeze,” which was presented with a visual distractor /ʕereʔ/ “sweat,” a semantic distractor /ʔatˤaʕ/ “cut,” and an unrelated distractor /weʔ eʕ/ “fall.” All four verbs, the target and the three distractors, were non-clustered monosyllabic verbs and share the same AoA (3.6 years old). It is noteworthy that PA verbs take prefixes and suffixes in the present tense (the imperfective), but for verb analyses and assessment, we referred to the stem verb.

The production tasks required naming of the object/action in the picture. Target words manipulated the same variables as in the comprehension task (e.g., /da:n/ “ear”: monosyllabic, cluster, AoA = 2.6). Alpha Cronbach reliability across all tested words in comprehension and production combined was α = 0.93 (see Appendix B – PA-CLT items).

MSA diglossic lexical task (MSA-DigLT). The MSA-DigLT was developed to test children’s receptive and expressive knowledge of nouns and verbs in MSA, taking into consideration the lexico-phonological distance of each item from PA. Five kindergarten teachers were asked to rate on a Likert scale of 1–5 the familiarity levels of 90 nouns and 90 verbs in MSA that are expected to be familiar to five-year-old children (from 1 = not familiar at all to 5 = very familiar). Based on these ratings, 30 nouns and 30 verbs, which were rated as “highly familiar” by all raters, were selected in three-word distance categories: identical, cognate, and unique MSA words (N = 10 per distance category per grammatical class). Images for the picture selection (comprehension) tasks and picture naming (production) tasks were selected from the original CLT pool of images (Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015) and supplemented by items from ClipArt. Three distractors were used for the comprehension task: a semantic categorical/associative distractor, a visual distractor (part of whole), and a phonological semantically unrelated distractor. For instance, /darraja/ “bicycle” a unique MSA noun for speakers of PA, was presented together with the three distractors: /xuːða/ “helmet” – an associatively related distractor, /ʕajal/ “wheel” – a visual distractor (part of whole), and /daraj/ “stairs” – a phonological yet semantically unrelated distractor. Similarly, the target verb /jaʒlis/ “sit down” was presented with a phonological distractor /jalbis:/ “wear,” a semantic distractor /jaktub/ “write,” and a visual distractor /juʃahid/ “watch.” The production task required children to produce the word for the object/action represented in the picture. Since the same words were used in both the comprehension and the production tasks, the production tasks were administered before the comprehension tasks and in different sessions at least a week apart. As with the PA-CLT, verbs in the MSA-DigLT were analysed and assessed at the root (stem) level. Alpha Cronbach reliability across all tested words in comprehension and production combined was α = 0.95 (see Appendix C – MSA-DigLT items, https://osf.io/wuk5n/files/osfstorage).

2.3. Procedure

Data were collected by three Ph.D. students who are native speakers of the dialects targeted in this study. Task administration took place individually in a quiet room at the kindergarten centres. Data collection was administered within four non-consecutive sessions, each 20 minutes long, alongside other tasks that targeted the acquisition of other aspects of PA. Data collection was done in the kindergartens during COVID-19 period with providing the required medical examinations and the special permissions that were given by all people in charge when there was no Quarantine. Tasks were ordered as follows: PA-CLT production (nouns and verbs) tasks, MSA-DigLT production (nouns and verbs) tasks, PA-CLT comprehension (nouns and verbs) tasks, and MSA-DigLT vocabulary comprehension (nouns and verbs) tasks. Pictures of target items, together with the distractors for the comprehension tasks, were displayed on a computer screen. In the MSA production tasks, and in order to elicit the lexical items in MSA, children were interviewed in MSA and were told to “speak like” cartoon heroes or news broadcasts and say the word the cartoon hero would use.

2.4. Data analysis

To test our hypotheses, we aggregated successful responses on each task and then generated percentage scores. The marking scheme for both lexical tasks was 1 for correct response and 0 for incorrect/no response. For each task, we computed percentage correct. We calculated the mean percentage of correct responses by modality (comprehension and production) and grammatical class (nouns and verbs) for PA-CLT and MSA-DigLT. For MSA-DigLT, we calculated the mean percentage correct as a function of lexical-phonological distance (identical, cognate, and unique).

To test comparisons across the two language varieties, we built Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE; Hardin & Hilbe, Reference Hardin and Hilbe2013) model with observations clustered by participant with an exchangeable working correlation. The study’s fixed effects concerned modality (comprehension and production), grammatical class (nouns and verbs), distance (identical, cognate, and unique), with age as a covariate. In this modelling approach, we aimed to explain comprehension and production of words by means of word distance category (identical, cognate, and unique) and grammatical class (nouns and verbs). In addition, by this GEE (GEE; Hardin & Hilbe, Reference Hardin and Hilbe2013) model, we tested the contribution of lexical knowledge in PA to lexical knowledge in MSA (by comparing children’s performances in PA-CLT and in MSA-DigLT). Moreover, because the success rates could not be tested within the normal distribution assumption, we used the non-symmetric Gamma distribution for the number of correct responses as the outcome, where cases of a zero success received a small value to include in the analysis as Gamma distribution requires strictly positive values. We examined differences in post hoc multiple comparisons (across distance and grammatical class) in comprehension and production as well as their interaction with the spoken language. After relating PA-CLT to MSA-DigLT, we proceed to consider two-way interactions with PA-CLT and a three-way analysis of the following: distance × grammatical class × PA-CLT. We assessed how PA affected nouns and verbs specifically through a three-way interaction to produce the six groups. For categorical two-way interactions, the within- and between-group differences are plotted, and the decompositions involving PA are listed in a separate table.

We used GEE to model population-averaged effects with robust (sandwich) standard errors. Observations were clustered by participant, and we assumed an exchangeable working correlation, under which the correlation between any two observations from the same participant is constant. Fixed effects included modality (comprehension and production), grammatical class (nouns and verbs), and lexical-phonological distance (identical, cognate, and unique); age was entered as a covariate. Thanks to the GEE model, we could account for this correlation between PA-CLT and MSA-DigLT noun and verb comprehension and production. It allows to specify a correlation structure within subjects, which results in more consistent parameter estimates. In other words, this approach offers a clear perception of the interaction between variables to significantly enhance our understanding of conditions impacting lexical knowledge related to Arabic diglossia. To answer the research questions about the effect of modality (comprehension versus production), grammatical class (nouns versus verbs), and linguistic distance between PA and MSA (identical, cognate, and unique) on lexical access and retrieval, the GEE analysis was set up with these variables as fixed effects. The participant ID was included as a random effect.

3. Results

Children’s performance on the PA-CLT and the MSA-DigLT tasks is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean percentage (and MSA deviation) of performance on the PA-CLT and the MSA-DigLT task (n = 30)

To test the differences in the means reported in Table 1, we used post hoc rankings. Planned t-tests confirmed the post hoc ranking and showed that there were differences between nouns and verbs in comprehension and production. In comprehension tasks, it was easier to process nouns than verbs as shown by the analysis; in the PA-CLT, noun yielded the following: mean = 98.1, SE = 2.529, while verbs yielded lower scores: mean = 93.13, SE = 2.668, with a mean difference of 12.10 (p < 0.001). In the production tasks, unexpectedly, verbs yield higher scores than nouns, but the difference was not statistically significant. In the MSA-DigLT, both in comprehension (Wald χ 2(2) = 11.68, p = 0.003) and in production (Wald χ 2(2) = 6.706, p = 0.035), the interaction between distance and grammatical class was significant. This suggests that the grammatical category (nouns versus verbs) modulates distance’ effects on task performance.

Post hoc tests confirmed: comprehension > production; nouns > verbs; and significant distance × grammatical class interactions in both modalities. For nouns, the analysis indicated a clear hierarchy in performance, with comprehension tasks yielding significantly higher accuracy rates compared to production tasks. Similarly, for verbs, comprehension tasks were associated with better performance than production tasks, though the disparity was less pronounced than for nouns. These findings suggest that while both nouns and verbs are more readily processed in comprehension than in production, nouns exhibit a more marked advantage in comprehension. Distance effect was differently affected by grammatical class and modality – more in production than comprehension and more in verbs than nouns. A detailed analysis will be presented in the distance effect section below and will be related to in the discussion section.

The second research question addressed the contribution of PA lexical knowledge to MSA lexical knowledge. To answer this question, we firstly correlated PA-CLT results with MSA-DigLT. The results showed that PA-CLT results on knowledge of nouns correlated with noun knowledge in MSA within both modalities – comprehension and production – and across both distance categories – cognate and unique (Appendix D – Table 1, https://osf.io/wuk5n/files/osfstorage). In the case of verbs, a significant correlation was only observed in the comprehension modality and it was limited to cognate words, namely, PA verb knowledge only correlated with cognate verb knowledge.

To better understand the relationship between lexical skills in PA and in MSA, a regression analysis was used (GEE; Hardin & Hilbe, Reference Hardin and Hilbe2013 model), in which lexical knowledge was measured six times, three times on nouns and three times on verbs, and each time addressing words from a different distance: identical, cognate, and unique.

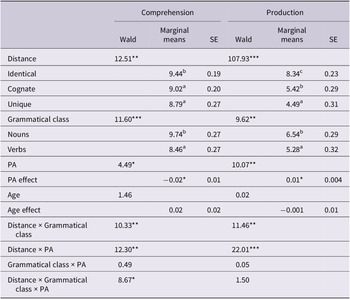

Table 2 shows the GEE modelling results followed by a marginal mean ranking when the main effect was found significant.

Table 2. Word distances and PA effects on MSA-DigLT word comprehension and production performance

*** p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Latin letters for marginal mean ranking from the lowest (a).

Table 2 shows that the main effects of both distance and grammatical class were significant (Wald χ 2(2) = 12.51, p < 0.01; Wald χ 2(1) = 11.60, p < 0.001, respectively) in the word comprehension analysis of the MSA-DigLT. Moreover, PA, namely performance on the PA-CLT task, showed a significant effect on word comprehension (Wald χ 2(1) = 4.49, p < 0.05), and an even stronger effect on word production (Wald χ 2(2) = 107.93, p < 0.001). The post hoc ranking of word distance types shows highest comprehension in identical words, and lower comprehension in cognate and unique words alike, regardless of the grammatical class, and comprehension was higher in nouns in comparison to verb, regardless of the distance type. Two out of the three two-way interactions were found significant. The interaction effect between grammatical class and distance in word comprehension (Wald χ 2(2) = 10.33, p < 0.01) is presented in Figure 1.

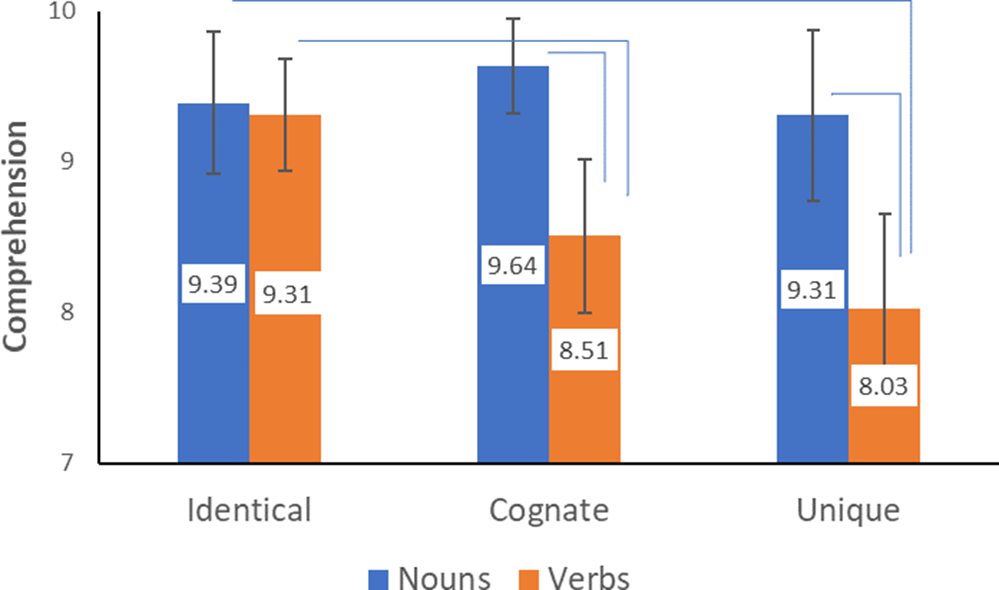

Figure 1. Interactions of distance and grammatical class in comprehension tasks – MSA-DigLT. Note: Blue lines show which marginal means differed one from another.

Figure 1 shows that the comprehension levels of nouns and verbs in identical words were similar. However, noun comprehension levels were extremely higher in comparison to verb comprehension in cognate and unique words. Moreover, verb comprehension of cognate and unique words was lower in comparison to both verbs and nouns of identical words.

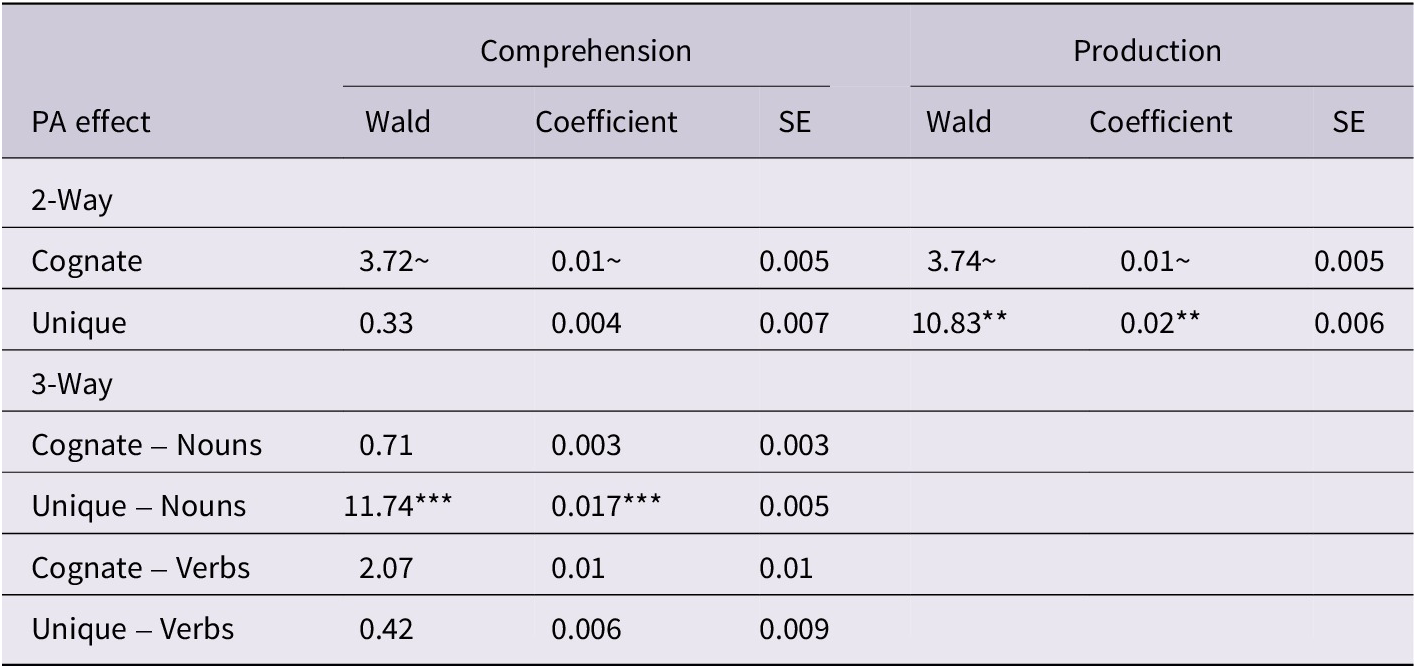

In addition, the interaction with distance type indicated possible differences in the effect of PA lexical knowledge on word comprehension across the word distance types cognate and unique; the results on the identical items were excluded (as the name implies, identical means that there is no distance in the lexical representation between PA and MSA; thus cannot teach us about the impact of PA lexical knowledge on MSA vocabulary acquisition). The different effects are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Interaction decomposition between distance and PA on comprehension and production – MSA-DigLT

*** p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

The upper left part of Table 3 demonstrates that, across the comprehension tasks, the effect of PA lexical knowledge on cognate words was close to significance (Wald’s = 3.72, p < 0.10), but not on unique words. In the production task, however, PA effect was significantly positive across unique words (Wald χ 2(1) = 10.83, p < 0.001).

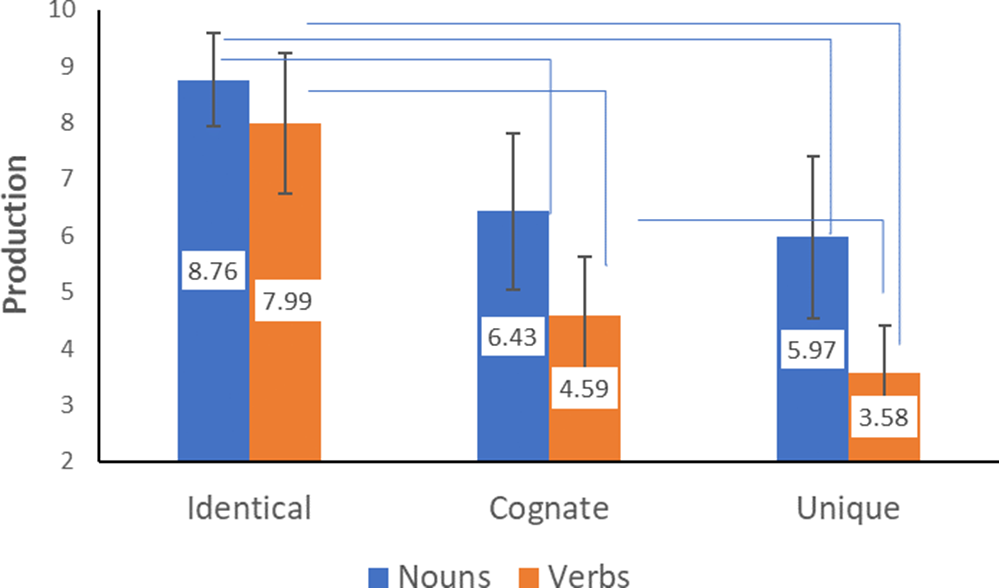

Lastly, the three-way interaction decomposition is shown in the lower left part for word comprehension. The only time in which PA showed an effect on word comprehension was for unique nouns (b = 0.017; Wald χ 2(1) = 11.74, p < 0.001), whereas across all other combinations of distance and grammatical class categories, PA showed no significant effect on word comprehension. Similar results are shown in Figure 2 for word production (Wald χ 2(2) = 11.46, p < 0.001), that is, no difference in identical words but the results of cognate and unique nouns were higher in comparison to verb production. Lastly, the three-way interaction analysis of word production resulted in no effect of PA on any of the compared pairs.

Figure 2. Interactions of distance and grammatical class in production tasks – MSA-DigLT. Note: Blue lines show which marginal m means differed one from another.

It is noteworthy that the children in our sample varied in age (65–78 months) and because language grows quickly during this maturational period, age was entered into the analysis as a predictor. However, the results did not show that the effect of age was significant.

In sum, our results demonstrate the role of modality and grammatical class in lexical knowledge in PA as well as the role of modality, grammatical class, and linguistic distance from PA in lexical knowledge in MSA. The results also demonstrate the interdependence between lexical knowledge in PA and in MSA.

As for the role of distance in MSA-DigLT, in the comprehension modality, our results showed an effect of distance with identical words being more easily comprehended than cognate or unique words, with no difference between the two latter types of words. Unexpectedly, there was no effect of PA lexical comprehension, as measured using the PA-CLT, on the comprehension of MSA words. Regarding the production of words on the MSA-DigLT task, the results showed again that distance had a strong effect on production, and with a significant gradation between all three types: from identical words to cognate to unique words. Contrary to what was reported for comprehension, PA lexical knowledge showed a significant effect on the production of MSA words, in particular the production of those words that are distant: cognate and unique words.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated lexical skills of typically developing PA-speaking kindergarten children in their spoken Arabic vernacular (PA) and their lexical skills in modern MSA Arabic (MSA). The first aim of the current study was to examine the role of modality (comprehension and production), and grammatical class (nouns and verbs) in lexical knowledge in PA, along with the role lexical-phonological distance (identical, cognate, and unique) in lexical knowledge in MSA.

4.1. Comprehension versus production

The results of the study showed that modality is associated with lexical knowledge in children. In both PA and MSA, children’s comprehension was consistently higher than their production, regardless of grammatical class (nouns and verbs) or lexical-phonological distance (identical, cognate, and unique). This pattern is consistent with earlier research (Clark & Casillas, Reference Clark, Casillas and Allan2015; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Izumi, Reference Izumi2003; Reznick & Goldfield, Reference Reznick and Goldfield1992; Swain, Reference Swain1993). In addition, these results extend previously documented findings consistent with the output hypothesis (Swain, Reference Swain1993), showing that in Arabic diglossia too, as in monolingual and bilingual settings, production is more complex and requires more demanding skills in terms of long-term memory and lexical access than comprehension (Clark & Casillas, Reference Clark, Casillas and Allan2015; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Izumi, Reference Izumi2003; Reznick & Goldfield, Reference Reznick and Goldfield1992; Swain, Reference Swain1993). It is noteworthy that the generalizability of the results may be constrained by the ceiling results with a high degree of homogeneity, especially for comprehension, which may reflect the methodology and be item-specific of the CLT design targeting a tight age range, as well as the focus on children with typical development and exclusion of children with developmental language deficits (Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015). These issue are for future research to address.

4.2. Nouns versus verbs

The results of the study revealed a noun advantage over verbs in both PA and MSA consistent with prior work across languages and bilectal contexts (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017; Bybee, Reference Bybee1985; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Gentner, Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982; Kambanaros et al., Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann and Michaelides2013, Reference Kambanaros, Grohmann, Michaelides and Theodorou2014; Khoury Aouad Saliby et al. (Reference Khoury Aouad Saliby, Dos Santos, Kouba Hreich and Messarra2017). Children scored higher in nouns than in verbs regardless of modality or lexical-phonological distance. The one non-significant exception in PA noun production may reflect item selection under CLT guidelines (Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015). This could be accounted for by the strict selection of the lexical items that followed the CLT guidelines leading to the inclusion of some less-familiar items, which some of the children did not recognize, such as a plow (for children who live in cities, as compared to villagers) or pineapple. That is, this non-significant difference might reflect the methodology used and be item-specific. Future studies could consider revising these few items.

In the Arabic context, in particular, the noun advantage over verbs may also be due to the morphological properties of nouns over verbs with Arabic nouns being less morphologically dense and variable than Arabic verbs. They may also be related to the large morphological distance between MSA and PA in verb inflectional morphology (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014; Shahbari-Kassem et al., Reference Shahbari-Kassem, Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2025). As such, Arabic verbs agree with the subject in number and gender, and they change their surface form depending on person and mood. This means that the same verb acquires different inflectional forms, and this might make it more difficult for children to acquire the verbal system. In contrast with verbs, nouns are less morphologically varied; they code number and gender differences (as well as case in MSA) making them less varied. In addition, all Arabic verbs are morphologically derivationally complex encoding a root and a word pattern. In contrast, many nouns are primitive and do not encode roots and patterns making them morphologically simpler (Ravid, Reference Ravid and Lieber2019; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014).

Thus, our results show that participants demonstrated more difficulty with verbs, which aligns with existing literature suggesting that the lexical representation and the morphological complexity of verbs influence performance (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Ravid, Reference Ravid and Lieber2019; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014; Shahbari-Kassem et al., Reference Shahbari-Kassem, Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2025; Shamsan, Reference Shamsan2005). These findings underscore the importance of considering morphological factors in language acquisition research and suggest potential areas for future exploration, such as interventions to support verb learning or cross-linguistic comparisons of morphological complexity in assessment and intervention. The morphological complexity inherent in Arabic verbs in particular may reflect their extensive inflectional paradigms for tense, aspect, mood, person, and number and is often accompanied with challenges in both elicitation and acquisition, especially when compared to nouns. This complexity is associated with increased difficulty for language learners, as mastering the various forms and rules associated with verbs can result in errors or delays in acquisition. In contrast, nouns generally exhibit simpler morphological structures, primarily involving inflections for number and case, making them more accessible for learners. Overall, these findings are consistent with the view that verb morphology and lexical representation are associated with lower performance (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Ravid, Reference Ravid and Lieber2019; Shahbari-Kassem et al., Reference Shahbari-Kassem, Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2025).

4.3. PA versus MSA

Our results showed better performance in PA-CLT lexical knowledge task than the MSA-DigLT across modalities and grammatical class. Differences between comprehension and production in the context of Arabic diglossia often involve differences in the language variety used: SpA versus MSA. In other words, in Arabic diglossia, speaking often happens in SpA, the only language of everyday speech, whereas comprehension can be in SpA or in MSA, with MSA being used most often in comprehension as it is not the language of oral interpersonal interaction by anyone MSA (Albirini, Reference Albirini2016; Bassiouney, Reference Bassiouney2009; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014). As a result, when children did not know a word in MSA, they reverted to the PA form; the more dominant and accurately represented lexical system (Saiegh-Haddad & Haj, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018). Crucially, the use of PA words was manifested to a different degree by the distance between the two varieties. This pattern is consistent with bilingual children’s code-switching when there is a lexical gap. Unlike the bilingual case, where this might be considered a strategy, in our case we see a real distance effect because, methodologically, in order to make sure that the children understood the task (to produce the MSA form), we told them explicitly that we ask them to use the language of their cartoon hero. Thus, when they knew the MSA word they produced it and when they did not, they used the PA equivalent lexical item. Moreover, when they produced the PA form, we explicitly asked if they knew the word in the MSA form (the language of books and cartoons).

Despite the unique nature of Arabic diglossia, the results are consistent with the evidence from other languages showing an advantage for comprehension over production in both PA and MSA (Clark & Casillas, Reference Clark, Casillas and Allan2015; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Izumi, Reference Izumi2003; Reznick & Goldfield, Reference Reznick and Goldfield1992). This reflects the complexity of production over comprehension (Clark & Casillas, Reference Clark, Casillas and Allan2015; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Izumi, Reference Izumi2003; Reznick & Goldfield, Reference Reznick and Goldfield1992). In Arabic diglossia, differences in modality might interact with grammatical class, speakers of the language hear MSA (mainly, in the media) more than they actively use it for speech. As a result, MSA word representations are acquired mostly passively in comprehension whereas the PA words are used in both modalities: comprehension and production. This might result in a larger discrepancy between comprehension and production of words. This is especially so for verbs which encode many morpho-syntactic categories including person, number, gender, mood, and tense/aspect and agree with the subject in number, person, and gender (Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005). In accordance with this prediction, our results revealed better performance on the comprehension tasks compared to the production tasks; a main effect of grammatical class, that is, children performed better on nouns compared to verbs; and an interaction effect of grammatical class by modality, with the gap between comprehension and production smaller for verbs than for nouns (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017).

4.4. The lexical-phonological distance (identical, cognate, and unique) factor in MSA lexical knowledge

In addition to modality and grammatical class, we examined the role of lexical-phonological distance in MSA lexical knowledge. The current study tested the role of lexical-phonological distance as a factor in MSA lexical knowledge. The two phonological forms of words in the two varieties can be identical, partially overlapping (cognate words) or completely different in each variety (unique words) (Saiegh-Haddad & Spolsky, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Spolsky, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014). Our results revealed that noun comprehension showed minimal difference between the three lexical-phonological distance categories which may reflect familiarity and ceiling performance. In other words, our choice of items (highly familiar MSA nouns) lowered variance, obscuring the true influence of distance. This aligns with evidence that MSA narrative comprehension by preschoolers is preserved despite diglossic distance (Kawar et al., Reference Kawar, Saiegh-Haddad and Armon-Lotem2023; Mahamid & Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Mahamid and Saiegh-Haddad2025); when contextual or semantic support is rich, children are able to map MSA forms to pre-existing conceptual representations with little cost.

Verb comprehension demonstrated a similarity between cognate and unique with both being lower than identical. For production, however, our results revealed a similarity between cognate and unique nouns with both being lower than identical, but a full three-way gradation for verb production. Moreover, a minimal cognate facilitation effect (De Groot, Reference De Groot2011; Dijkstra et al., Reference Dijkstra, Miwa, Brummelhuis, Sappelli and Baayen2010; Kroll & Bialystok, Reference Kroll and Bialystok2013) is observed when the cognates are compared to the unique, yet with an overall ceiling effect for the items tested. In contrast, our results demonstrated no facilitation effect for cognates in verb comprehension. The absence of cognate facilitation in verb comprehension is consistent with the findings that small phonological mismatches can reduce cognate benefits and lower representational quality (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Caramazza and Sebastian-Galles2005; De Groot, Reference De Groot2011; Dijkstra et al., Reference Dijkstra, Miwa, Brummelhuis, Sappelli and Baayen2010; Kroll & Bialystok, Reference Kroll and Bialystok2013; Saiegh-Haddad & Haj, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018). It may also reflect the complexity of inflected prompts in MSA (tense, mood, number, person, gender, and aspect) relative to PA (Ryding, Reference Ryding2005; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Henkin-Roitfarb, Saiegh-Haddad and Joshi2014) and the noun–verb differences in concreteness and inflectional load (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985; Gentner, Reference Gentner and Kuczaj1982; Haman et al., Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Hansen, Simonsen, Chiat, Bjekić and Armon-Lotem2017; Joubran-Awadie & Shalhoub-Awwad, Reference Joubran-Awadie and Shalhoub-Awwad2023; Khoury Aouad Saliby et al., Reference Khoury Aouad Saliby, Dos Santos, Kouba Hreich and Messarra2017; Ryding, Reference Ryding2005). A frequency account is also plausible and warrants further study (Metsala & Walley, Reference Metsala and Walley1998; Perfetti, Reference Perfetti2007).

For noun production, the lack of cognate facilitation is associated with blocked retrieval, consistent with the negative effects of neighbourhood density with high-frequency neighbours similar to lexical forms (De Cara & Goswami, Reference De Cara and Goswami2003; Luce, Reference Luce1986; Sears et al., Reference Sears, Hino and Lupker1995). In contrast, verb production showed a graded distance effect (identical > cognate > unique), consistent with prior work linking diglossic distance to difficulty in memory, phonological awareness, decoding, and lexical-phonological representations (Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2003, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2004, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2007; Saiegh-Haddad et al., Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Levin, Hende and Ziv2011, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Shahbari-Kassem and Schiff2020; Saiegh-Haddad & Haj, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018; Saiegh-Haddad & Ghawi-Dakwar, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Ghawi-Dakwar2017; Saiegh-Haddad & Schiff, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2016), and with low cognate facilitation relative to unique verbs (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Chen and Geva2019; Koda, Reference Koda, Koda and Zehler2008; Sherkina, Reference Sherkina2003).

Despite the lack of a cognate facilitation, the results from our MSA verb production reveal an interesting pattern of gradation in lexical-phonological distance effect with identical verbs being easier to produce than cognate verbs, and with unique verbs being the most difficult to produce. This aligns with previous research that shows that the phonological distance between PA and MSA has a negative effect on processing in memory, phonological awareness, word decoding, and lexical-phonological representations (Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2003, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2004, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2005, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2007; Saiegh-Haddad et al., Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Levin, Hende and Ziv2011, Reference Saiegh-Haddad, Shahbari-Kassem and Schiff2020; Saiegh-Haddad & Haj, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Haj2018; Saiegh-Haddad & Ghawi-Dakwar, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Ghawi-Dakwar2017; Saiegh-Haddad & Schiff, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2016). In addition, this distance effect resonates the cognate facilitation in MSA verb production with a significant higher performance on cognate verb production as compared to unique verb production (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Chen and Geva2019; Koda, Reference Koda, Koda and Zehler2008; Sherkina, Reference Sherkina2003).

4.5. The contribution of lexical knowledge in PA to lexical knowledge in MSA

The second goal of our study was to explore the contribution of PA lexical knowledge as reflected in performance on the PA-CLT to MSA lexical knowledge as reflected in performance on the MSA-DigLT. We predicted that children with higher scores in PA would perform better in MSA, building on their stronger lexical network (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Chen and Geva2019; Cummins, Reference Cummins1979) and supporting earlier reported of cross-lectal transfer and interdependence between language and literacy skills in PA and MSA (Saiegh-Haddad & Schiff, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2016, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2025; Zamlut, Reference Zamlut2011). Our results showed no broad association between PA lexical comprehension and MSA word comprehension, except for unique nouns. For production, however, PA lexical knowledge was associated with MSA production for both cognate and unique words.

While the effect of PA lexical knowledge on MSA word comprehension was not broadly significant, except notably for unique nouns, the results showed an observable effect of PA on MSA cognate comprehension. This may reflect the ceiling scores and minimal variability. In the MSA-DigLT, the ceiling scores on MSA word comprehension might reflect the familiarity of the items selected and with minimal variance significant correlations cannot be expected to emerge. The interaction of PA noun and verb comprehension and production with MSA distance type indicated a differential effect of PA on word comprehension across the lexical-phonological distances. Specifically, the contribution of the comprehension of PA lexical knowledge in predicting the comprehension of MSA lexical knowledge was significant for unique noun comprehension. This could be explained similarly to the noun–verb differences observed above, with nouns being more concrete on the one hand and less inflectionally complex on the other, making it possible to rely on general phonological representation. This finding resonates with earlier evidence from bilingual children demonstrating a cross-linguistic relationship between vocabulary knowledge in the two languages or language varieties (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Chen and Geva2019; Koda, Reference Koda, Koda and Zehler2008; Ringbom, Reference Ringbom and Rosa Alonso2016; Sherkina, Reference Sherkina2003). These results imply that children with rich PA lexical network are able to build on it when acquiring MSA.

While a cross-lectal transfer is non-consistent in comprehension, our results for production revealed that PA lexical knowledge had a significant contribution to MSA lexical knowledge across cognate and unique words. The results showed that PA lexical knowledge predicted children’s MSA production of cognate and unique lexical items, which were easier to produce when PA scores were higher. This finding provides further evidence for the cross-lectal relationship between skills in the two varieties (Alsherhi, Reference Alsherhi2021; Schiff & Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2018; Saiegh-Haddad & Schiff, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2025). Moreover, our findings imply that just as linguistic skills in SpA predict word reading and reading comprehension (Saiegh-Haddad & Schiff, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2025), lexical skills in SpA can predict lexical knowledge in MSA. These results are consistent with Cummins’ Interdependence Hypothesis and Common Underlying Proficiency (Cummins, Reference Cummins1979) and transfer of skills across the languages of bilectal speakers including in Arabic (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Chen and Geva2019; Cummins, Reference Cummins1979; Haj et al., Reference Haj, Saiegh-Haddad, Ghawi-Dakwar and Schiff2025; Schiff & Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Schiff and Saiegh-Haddad2018; Saiegh-Haddad, Reference Saiegh-Haddad2023; Saiegh-Haddad & Schiff, Reference Saiegh-Haddad and Schiff2025). This finding is not only novel but it has important educational and clinical implications.

5. Limitations and future research