Introduction

Childhood undernutrition remains a major health concern in many countries around the world. Regardless, a preventable condition, nearly 151 million children around the globe have stunted growth (Fanzo et al. Reference Fanzo, Hawkes, Udomkesmalee, Afshin, Allemandi, Assery, Baker, Battersby, Bhutta and Chen2018; FAO et al. 2024). Childhood stunting does not only reflect long term nutritional deficiencies but also impact cognitive and physical development in later stages of life (Black et al. Reference Black, Walker, Fernald, Andersen, DiGirolamo, Lu, McCoy, Fink, Shawar and Shiffman2017). Improvement in child nutritional status is expected to enhance economic productivity by 4 to 11% through gains in gross domestic product (Horton and Steckel Reference Horton and Steckel2013), conversely, economic burden of poor child linear growth, in terms of per capita income loss ranges from 5 to 7% (Galasso and Wagstaff Reference Galasso and Wagstaff2019; Galler et al. Reference Galler, Bryce, Waber, Zichlin, Fitzmaurice and Eaglesfield2012). Although national and international efforts translated into some progress, uneven outcomes remain evident across borders and within countries (Rehman et al. Reference Rehman, Qing and Cui2023; Ssentongo et al. Reference Ssentongo, Ssentongo, Ba, Ericson, Na, Gao, Fronterre, Chinchilli and Schiff2021).

Insufficient nutritional intake, inadequate healthcare access, and sub-optimal nurturing environment are well established factors of childhood stunting (Ali Reference Ali2021; Azriani et al. Reference Azriani, Qinthara, Yulita, Agustian, Zuhairini and Dhamayanti2024). These critical factors are shaped by women’s decision-making ability within the household through multiple pathways. For instance, participation of women in economic decisions—such as purchase and resource allocation—enables them to prioritize investments on nutritious food and quality healthcare, improving child nutritional status (Rehman et al. Reference Rehman, Ping and Razzaq2019; Soh Wenda et al. Reference Soh Wenda, Fon, Molua and Longang2024; Wassie et al. Reference Wassie, Tenagashaw and Tiruye2024). Conversely, women’s involvement in non-economic decisions which includes her own healthcare, freedom of movement, and control over birth spacing improves a child’s diet and overall well-being through better caregiving practices, access to critical information, and maintenance of a hygienic household environment (Kamiya et al. Reference Kamiya, Nomura, Ogino, Yoshikawa, Siengsounthone and Xangsayarath2018; Onah et al. Reference Onah, Horton and Hoddinott2021).

Despite the documented significance of women’s participation in household decisions in global health literature, the strength of this relationship is not consistent. The association between women’s decision-making ability and child nutritional status varies substantially depending on the domain of decision making, specific regional and cultural context (Santoso et al. Reference Santoso, Kerr, Hoddinott, Garigipati, Olmos and Young2019). These variations create few gaps in existing literature which this study aims to fill. Firstly, much of the existing literature is based on single cross-sectional datasets, which limits the ability to explore how the relationship between women decision-making and child stunting evolves overtime with changing socioeconomic conditions. Secondly, few studies have incorporated multilevel structure of the data which is crucial given that individuals are clustered within households, and households within communities (Santoso et al. Reference Santoso, Kerr, Hoddinott, Garigipati, Olmos and Young2019). The presence of hierarchies at different levels implies that observations are not independently distributed; ignoring this structure can lead to an overestimation of statistical significance and, consequently, incorrect inferences (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2011; Mahmood et al. Reference Mahmood, Abbas, Kumar and Somrongthong2020).

Lastly, despite Pakistan’s cultural, social and economic diversity, there is limited literature on the role of women’s participation in household decisions in relation to child nutritional security—particularly in terms of sub-national analysis and how this association has evolved overtime (Das et al. Reference Das, Achakzai and Bhutta2016). Like many other countries childhood stunting is still a challenging health concern for policy makers in Pakistan, where despite some progress in past two decades, 37% of children have poor linear growth with prominent regional disparities (Di Cesare et al. Reference Di Cesare, Bhatti, Soofi, Fortunato, Ezzati and Bhutta2015; Islam et al. Reference Islam, Ali, Majeed, Ali, Ahmed, Soofi and Bhutta2025; NIPS 2019). Existing studies that do examine the association between women’s status and child nutritional status provide contradictory findings. For instance, Hou (Reference Hou2015) and Shafiq et al. (Reference Shafiq, Hussain, Asif, Hwang, Jameel and Kanwel2019) found no clear link between a mother’s decision-making power and improved nutritional outcomes. However, Khalid and Martin (Reference Khalid and Martin2017) suggest lower odds of childhood stunting in female-headed households.

To address these gaps in literature, this study aims to explore association between women’s decision-making within household and childhood stunting by employing multilevel model using two survey rounds of nationally representative household data, PDHS 2012–13 and PDHS 2017–18. To capture decision-making ability, a composite index was constructed by using factor analysis from the responses related to women’s participation in different household decisions. Additionally, the separate effects of economic and non-economic decisions were examined to address concern that a composite index may mask the role of individual domains (Ravallion Reference Ravallion2010). Finally, this study also explores the stability of relationship between women’s decision-making and child nutritional growth overtime and strength of association across different geographical locations

Materials and methods

Data and study area

Data used in this study were accessed from two rounds of the nationally representative survey “Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys (PDHS)” conducted by the National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) in collaboration with the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) for the years 2012–13 and 2017–18. Pooling data from these two cross-sectional surveys offer the advantage to produce accurate estimates due to the larger number of observations and to evaluate the variations overtime. The dataset covers a range of socioeconomic and demographic variables, including age, education, employment, household assets, immunization, women’s status, and anthropometric indicators such as stunting and body mass index (BMI).

The PDHS employs a stratified, multistage cluster sampling method to collect data in urban and rural areas of Pakistan, covering all four provinces; Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK); and other regions including; Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT), Gilgit Baltistan, the Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). To maintain comparability across years, observations from AJK and FATA were excluded, as these regions were not surveyed in 2012–13. The stratification process was completed by dividing six regions into urban and rural areas which produced 12 strata. In first stage of sampling, the primary sampling units (PSUs)—also referred to as the enumeration blocks—were selected based on probability proportional to size within each stratum. The selection and structure of PSUs differ between urban and rural areas. In rural areas, one village is typically considered a single PSU, whereas urban areas are subdivided into two or three PSUs based on population density and administrative divisions. Each primary sampling unit comprises around 200–250 households. Within each PSU, households were categorized into low, middle, and high-income groups based on asset ownership, housing condition, and access to services. Based on the relatively homogeneous living condition, income level and general infrastructure, PSU can be used as a proxy to unobserved community level characteristics.

In the second stage of sampling, 28 households from each PSU were selected through systematic sampling with a random starting point. The total sample comprises 14,000 households from the 2013 round and 16,240 households from the 2018 round. After removing missing and inconsistent observations, the sample size for ever-married women with at least one child under 5 years of age reduced to 6,049 observations in both rounds.

Construction of variables

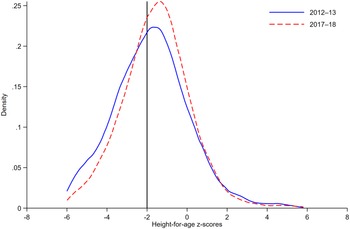

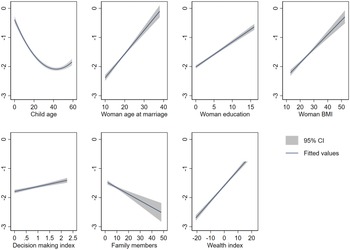

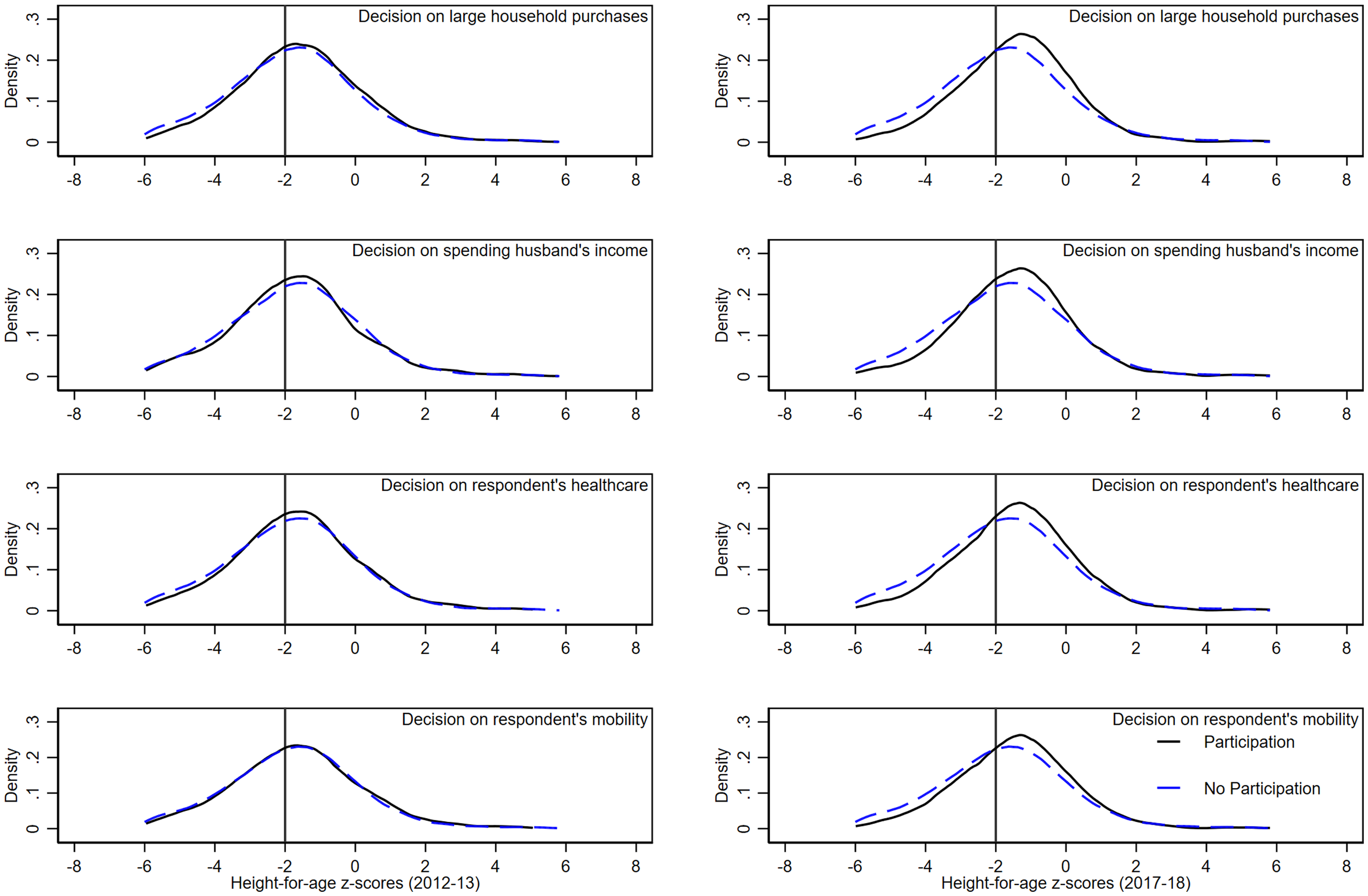

Dependent variable in this study is childhood stunting, measured as Height-for-Age z-score (HAZ), following 2006 growth standards of World Health Organization (WHO 2006). HAZ scores serve as a benchmark indicator that compare a child’s height to the median height of a healthy reference population of same age and sex. For this study, pre-calculated continuous HAZ scores were used for children under the age of five adjusted for sex and age in month from the PDHS datasets. The range of HAZ scores are between –6 and +6 standard deviation (SD) which is considered biologically plausible as per WHO standards. For robust analysis, two binary variables were created indicating stunted growth of a child if HAZ score is below –2 SD and severely stunted growth if HAZ is less than –3 SD. To visualize the distribution of child nutritional status, Kernel Density Estimates (KDE) were drawn, where the left-skewed distribution of HAZ indicates a high prevalence of child stunting (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Kernel Density Estimates of Height-for-Age z-Scores (0–5 years) by Survey Year.

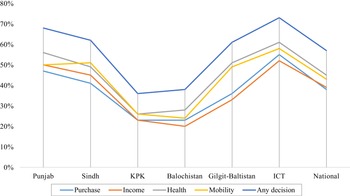

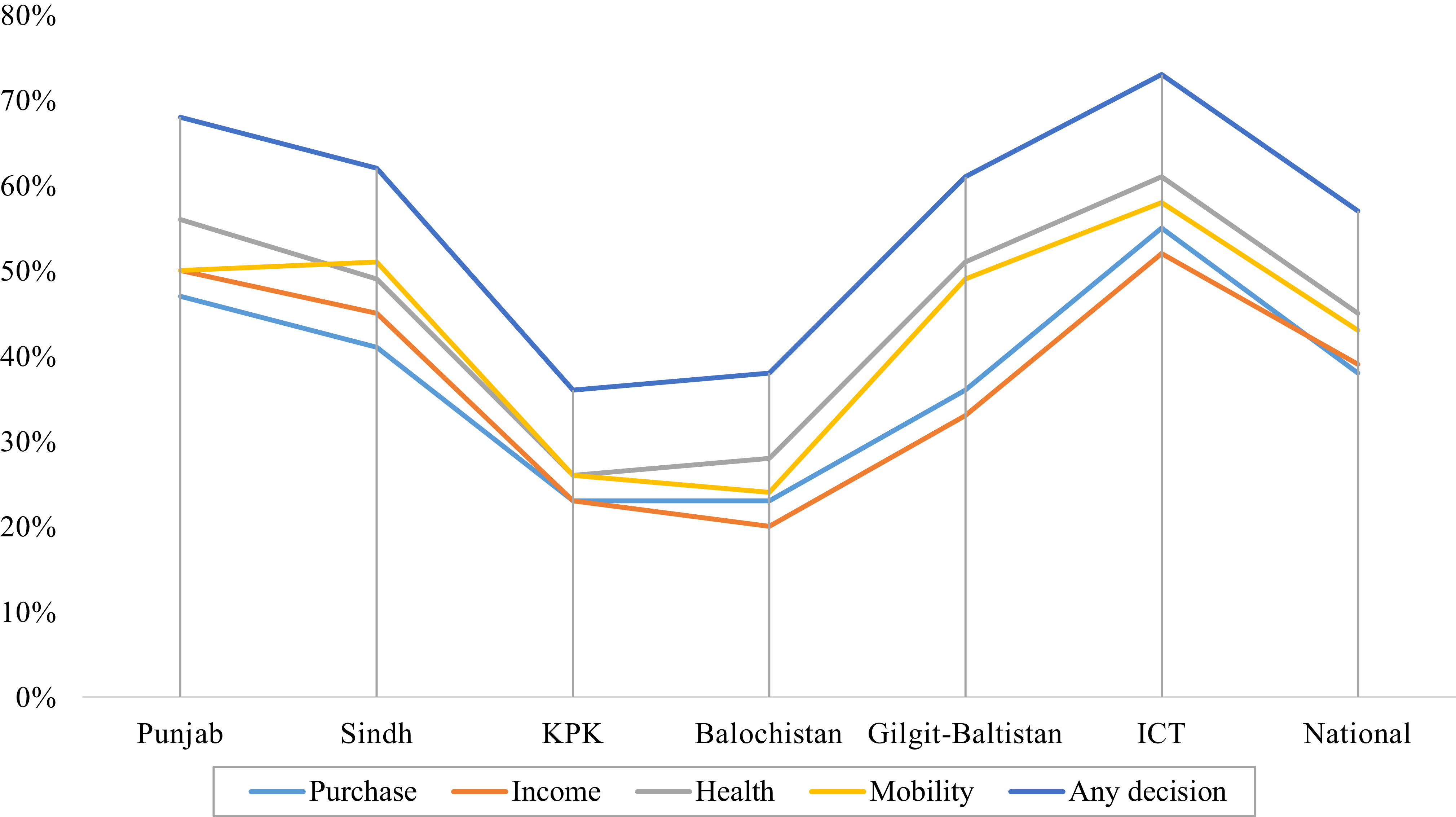

The explanatory variables of interest in the present study are women’s participation in household decision-making, broadly categorized into economic and non-economic domains. Economic decisions include household purchases decision and control over household income, while non-economic decisions refer to participation in decisions regarding women’s healthcare and mobility. During the survey, women were asked a series of questions to assess their decision-making ability: (1) who usually decides on large household purchases; (2) who usually decides how the husband’s income is spent; (3) who usually makes decisions regarding woman’s health care; (4) who decides on the woman’s mobility, specifically visiting family or relatives. Responses to these questions were: (i) the woman makes the decision alone; (ii) the woman makes the decision jointly with her husband; and (iii) the husband makes the decision alone or with the help of other family members. Binary variables were created for all decisions coded as “1” if a woman participates in the decision-making process (alone or jointly) and “0” otherwise. These binary variables were combined to construct a composite index using factor analysis based on tetrachoric correlations. The suitability of data on decision making for factor analysis were tested by using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. Both indicated that correlation matrix was not an identity matrix and the data is sufficiently correlated for factor analysis (see Table S1 for details). Figure 2 illustrates the percentage of women participating in various household decisions across different regions of Pakistan. It is evident that 40% to 60% of women reported involvement in household decisions at national level with distinct regional differences.

Figure 2. Regional Variation in Women’s Participation in Household Decision-Making by Domain (%).

To strengthen the robustness of results, two additional variables were constructed related to women’s decision-making. First, an ordered categorical variable was created ranging from “0” to “4”, representing the number of household decisions in which a woman participated. Second, a binary variable was created, coded as “0” for no participation and “1” for participation in at least one decision.

A range of control variables were also incorporated to account for individual, household, and community level factors. At the Individual level, child-specific variables include age and gender, while women characteristics comprised age at marriage, body mass index (BMI), education, and employment status. Household level variables include wealth index, family size, access to safe drinking water, and availability of hygienic sanitation facilities. At the community level, this study accounted for average level of women’s education, average proportion of women who received at least four antenatal visits (access to maternal health services), place of residence (urban/rural), and geographic location. Considering the high correlation between average women’s education and health access in a community, a combined variable was created by taking mean of these two indicators to represent an educated and healthy community.

Among explanatory variables, child age, women’s decision-making index, age at marriage, BMI, education, and family size were included as continuous variables in the model, while the rest were specified as binary variables, excluding wealth index. Although the DHS dataset has a wealth index variable, it is only valid for a single point in time. Therefore, a new wealth index was constructed using confirmatory factor analysis. This index was derived from 41 binary variables representing moveable and immovable household assets, along with two continuous variables; the number of members sleeping in a single room and land ownership. The availability of safe drinking water and hygienic sanitation variables were removed from the index because of their distinct and direct effect on child nutritional growth. The resulting index was divided into three categorize, “rich”, “middle”, and “poor”. Table 1 shows weighted descriptive statistics for child HAZ and all covariates used in this study.

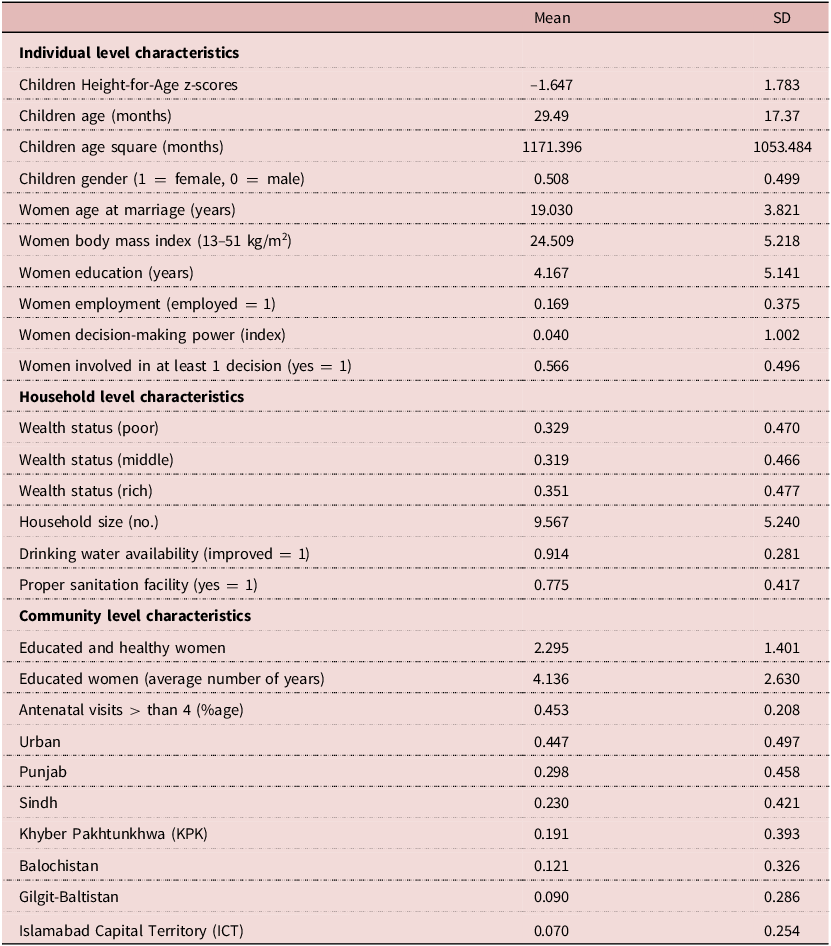

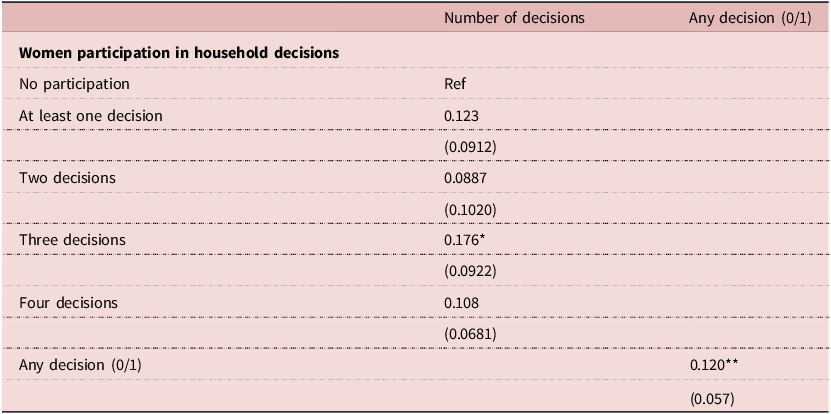

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Variables Used in this Study (n = 6049)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on PDHS 2012–13, 2017–18.

Econometric specification

Multilevel model was incorporated to estimate the association between women’s decision-making power and child long term nutritional status.

Three levels were defined: individual characteristics of women and children at the first level, household-related variables at the second level, and community variables at the third level.

Following Subedi (Reference Subedi2005), the first-level model is given as:

Where

![]() $H$

is the child HAZ score;

$H$

is the child HAZ score;

![]() $a$

denotes individual-level characteristics;

$a$

denotes individual-level characteristics;

![]() $\pi $

shows the coefficients to be estimated; and

$\pi $

shows the coefficients to be estimated; and

![]() $e$

is the error term. The variables in the equations contain three subscripts, i, j, and k, which represent the hierarchical structure of the data at the individual, household, and community levels, respectively.

$e$

is the error term. The variables in the equations contain three subscripts, i, j, and k, which represent the hierarchical structure of the data at the individual, household, and community levels, respectively.

The second-level model is formulated using the first-level intercept and slopes as outcomes;

Here,

![]() $\beta $

are the coefficients of the intercept and slopes,

$\beta $

are the coefficients of the intercept and slopes,

![]() $X$

are the household-level characteristics, and

$X$

are the household-level characteristics, and

![]() $\gamma $

are random effects for household j and community k.

$\gamma $

are random effects for household j and community k.

The third-level model was formulated by using the second-level intercept and slopes as outcomes;

Here,

![]() $\gamma $

are the coefficients,

$\gamma $

are the coefficients,

![]() $W$

are the community variables and

$W$

are the community variables and

![]() $\mu $

are random effects associated with k community.

$\mu $

are random effects associated with k community.

The single equation can be created by first substituting equations (4)-(7) into equations (2) and (3) and then substituting the newly formed equations (2) and (3) into (1).

The first four terms on the right side of equation 8 are deterministic, and the last three terms are stochastic. The estimation of this equation was accomplished in four steps:

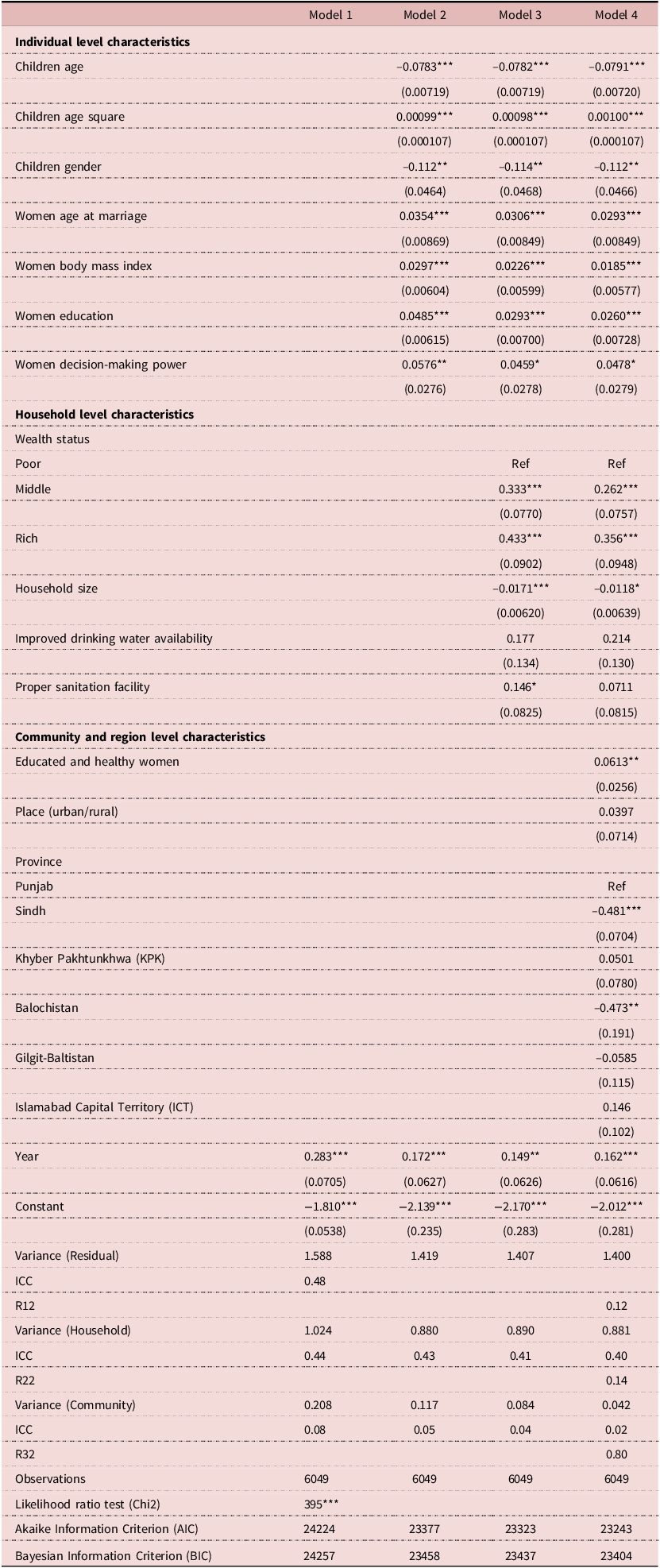

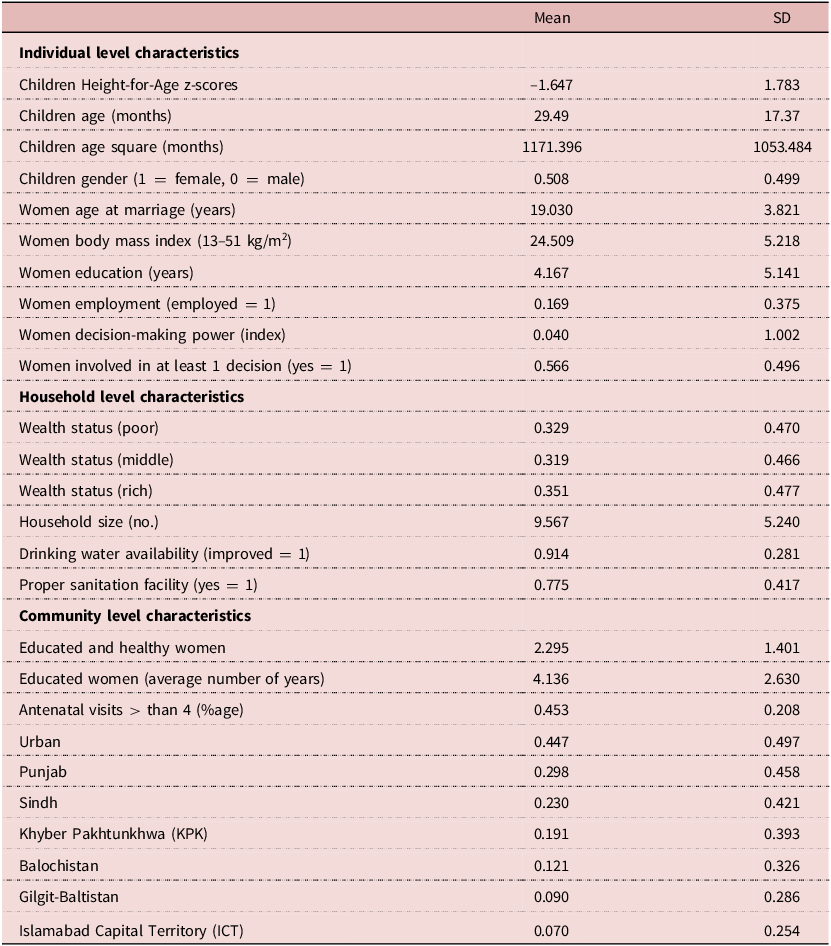

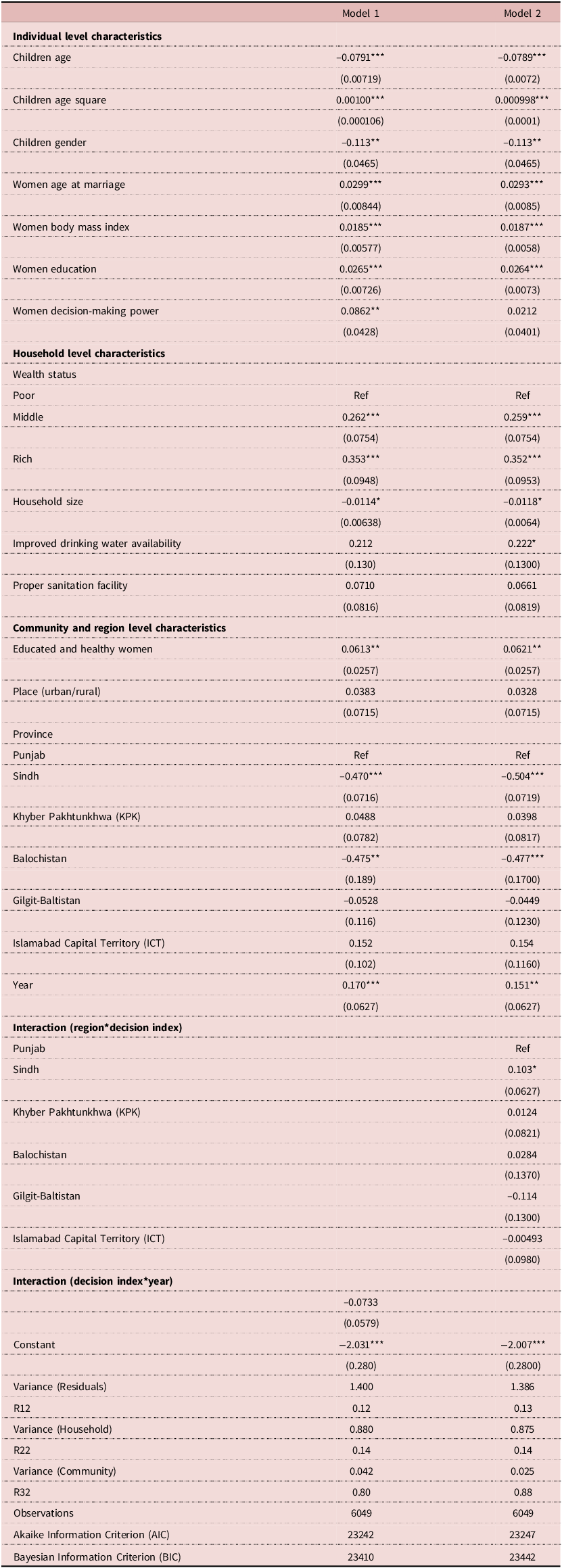

Step 1: At first, the intercept-only model (1) was estimated by specifying the hierarchical levels of the data: the individual, household, and community levels. The intercept-only model provides estimates of the interclass correlations. According to these estimates, 48% of the total variation in childhood stunting is associated with individual characteristics, 44% is associated with household-level variables, and 8% of the variation is at the community level (Table 2). As the magnitude of the variations is nontrivial at each level, this justifies the use of three-level modelling. Step 2: Next, individual-level covariates were included to explain variation in the child Height-for-Age z-score and observed the improvement in model fit compared to the intercept-only-model. Step 3: Subsequently, household-level variables were added to account for variation across households in child Height-for-Age z-score. Step 4: In the final model, community-level variables were incorporated to account for variations across communities. Two interactions terms of survey year and region variable with women’s decision-making index were added in separate models to observe changes overtime and across regions. Survey weights provided by PDHS were applied in all analyses to adjust for complex survey design and to account for unequal selection probabilities across regions.

Table 2. Maximum Likelihood Estimates of Height-for-Age z-Scores (0–5 years)

Source: Authors’ calculations using PDHS 2012-13, 2017-18. Standard errors are in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Results

Non-parametric analysis

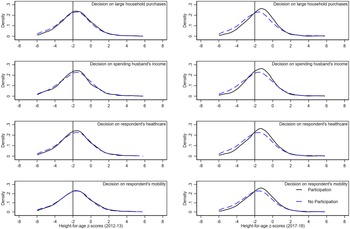

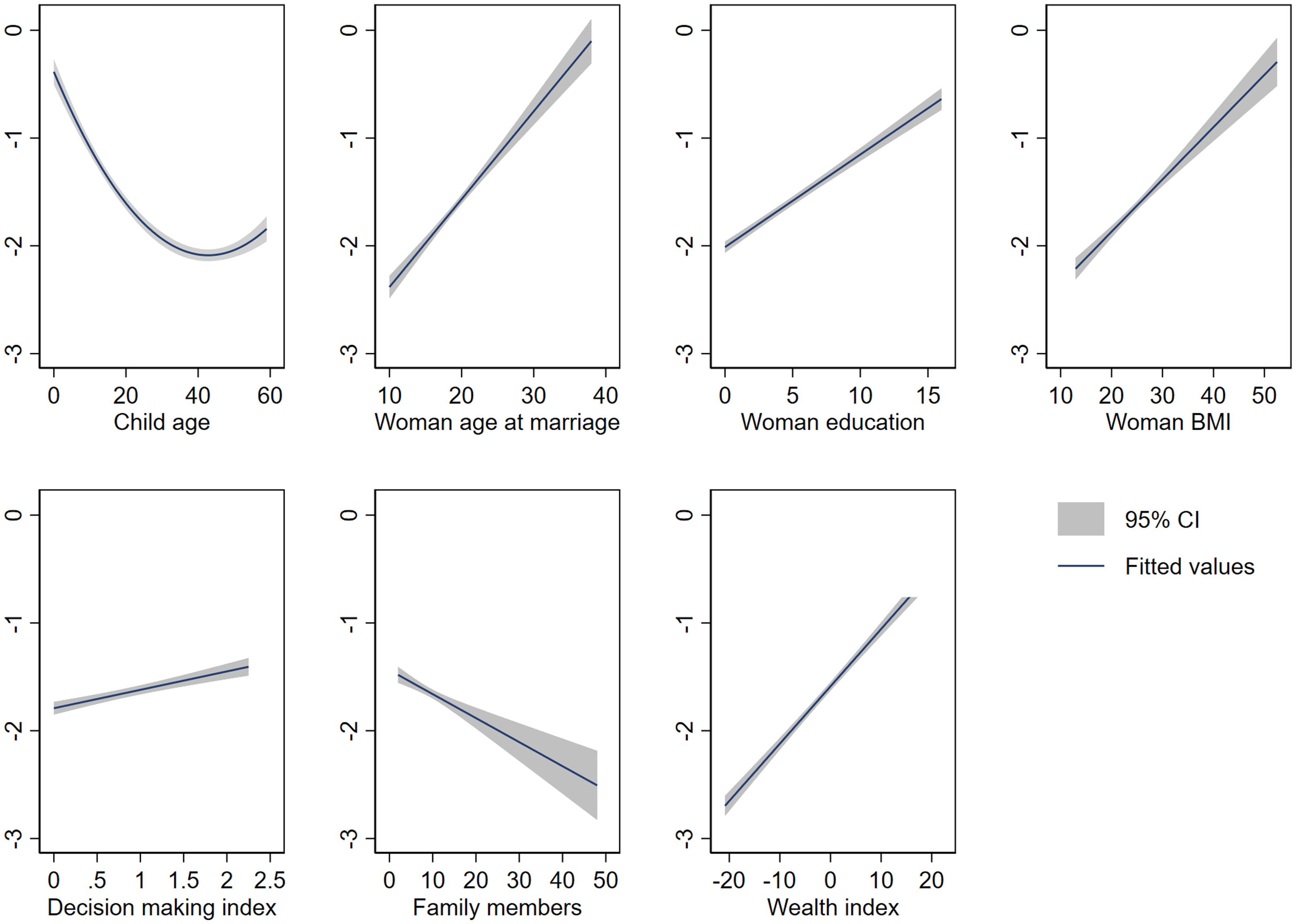

Before conducting the regression analysis, a nonparametric exploratory analysis was performed to examine the relationships between the dependent and independent variables. To accomplish that, two-way scatterplots were plotted between HAZ and explanatory variables on the right side of equation 8. Figure 3 shows that the associations between child HAZ and all explanatory variables appear linear with the exception of child’s age which exhibits a quadratic pattern. Thus, the square of child’s age was included for parametric analysis to account for this nonlinearity. To visualize the association between women’s decision-making power and child HAZ, kernel density estimates of HAZ for all decisions (Figure 4) were generated. Across all panels, the results present a preliminary idea that children of women who participate in household decision-making tend to have better nutritional outcomes with slight improvement across survey years.

Figure 3. Relationship Between Height-for-Age z-Scores and Explanatory Variables.

Figure 4. Kernel Density Estimates of Height-for-Age z-Scores by Women’s Participation in Household Decisions by Survey Year.

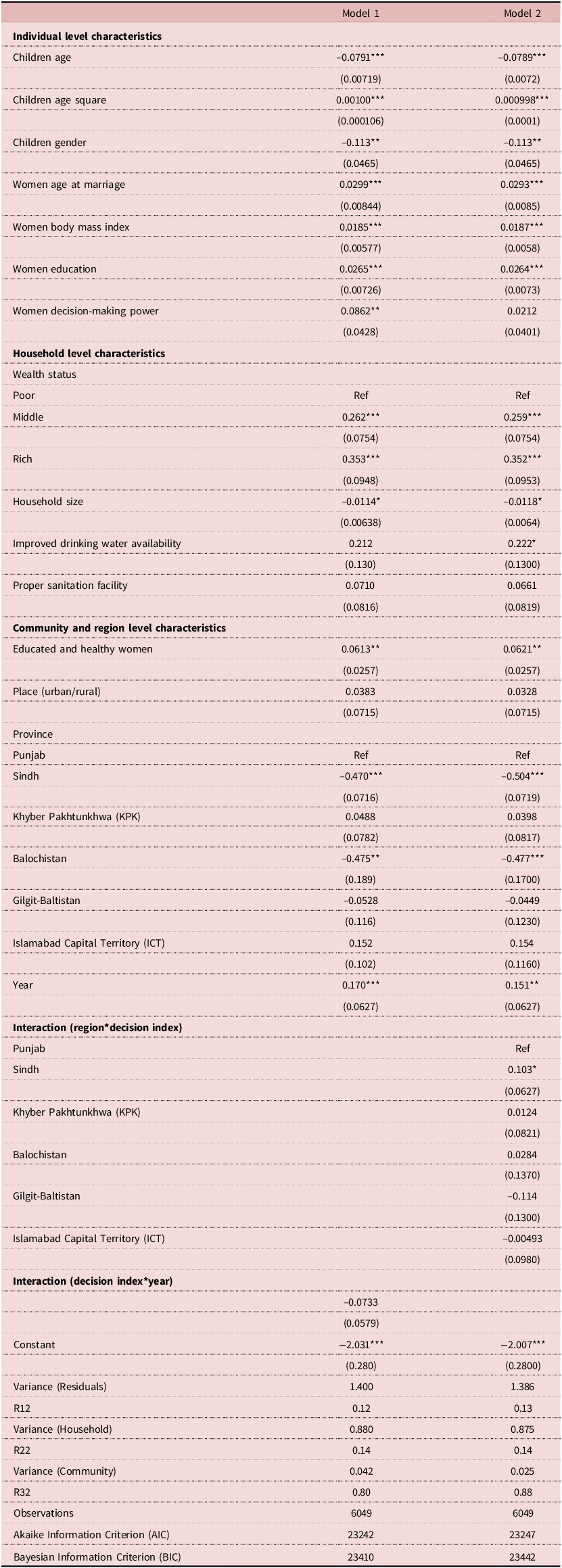

Parametric analysis: multilevel model estimates

The maximum likelihood estimates are presented in Table 2. All predictor variables were added to the models in four steps, starting with the basic intercept-only model (Model1), followed by the inclusion of individual-level variables in Model2. The last two columns show the estimated associations of household and community characteristics with childhood stunting (Model3–4). The likelihood ratio test obtained from Model1 indicated that instead of using the conventional ordinary least squares model, the multilevel model was a better fit for this study, with a statistical significance of more than 1% (χ2 = 395).

Model4 in table 2 shows that aggregate variation explained by community and regional characteristics is highest (R32 = 0.80), followed by household (R22 = 0.14), and individual level (R12 = 0.12). Results showed that the long-term nutritional score of children is positively associated with women’s involvement in the decision-making process. More specifically, children of women who participate in household decisions are likely to have a better nutritional score by 0.048 SD than their counterparts. The coefficient value is slightly lower than that of Model1 with individual-level variables but remains statistically significant at the 10 percent confidence level after adding household and community variables.

The coefficients of the explanatory variables related to some other characteristics of women, such as education, age at marriage, and nutritional status, are also positive and significant. More precisely, this study predicted a 0.026 SD increase in children’s HAZ with one-year increase in women’s education, and a 0.029 SD improvement in children’s long-term nutritional status was observed by delaying women’s marriage by one year. A child is more prone to poor linear growth if a woman has a lower body mass index. Specifically, each unit increase in the women’s BMI is predicted to improve children HAZ scores by 0.019 SD. Results also indicated that female children are more likely to have higher HAZ than male children by 0.11 SD at 5% significance level.

The second set of covariates are household-level characteristics, which directly influence the environment children live in, thus effecting their normal growth. Compared with those living in less wealthy households, children living in middle-income families are expected to have Height-for-Age z-scores that are 0.26 times greater, while members of rich families are predicted to have 0.36 times greater HAZ scores. Children living in large families are at a higher risk of experiencing poor linear growth than children living in smaller families. The coefficient of hygienic sanitation was positive and significant at the 10 percent confidence level, but turned insignificant after the addition of community and regional characteristics. Finally, the safe drinking water availability coefficient is positive but not significant.

At the community level, women average education and access to health services significantly improve child nutritional outcomes. More specifically, children living in more educated and health-accessible communities are predicted to have higher HAZ scores by 0.06 SD with 5% significance. Generally, it had been observed that children living in rural areas are more prone to poor nutritional growth, however, no significant difference was found in this sample. Compared to Punjab, children living in Sindh and Balochistan have significantly lower chance of normal nutritional growth by 0.48, and 0.47 SD respectively.

Interactions: Two-way interactions were included to observe that whether the association between women’s decision-making power and childhood stunting changed overtime and across regions. The coefficient of year interaction was not statistically significant indicating that the effect of women’s decision-making on child nutritional status remained relatively stable across survey years (Model1 Table 3). Regional interactions show that the association between women’s decision-making ability is heterogeneous across different regions. Using Punjab as reference region, children living in Sindh are better off by 0.10 SD associated with women’s involvement in household decision-making, with 10% statistical significance. In contrast, other regions demonstrated mixed coefficient directions, none of which were statistically significant (Model2 Table 3).

Table 3. Maximum Likelihood Estimates of Height-for-Age z-Scores (0–5 years) with Interactions

Source: Authors’ calculations using PDHS 2012-13, 2017-18. Standard errors are in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

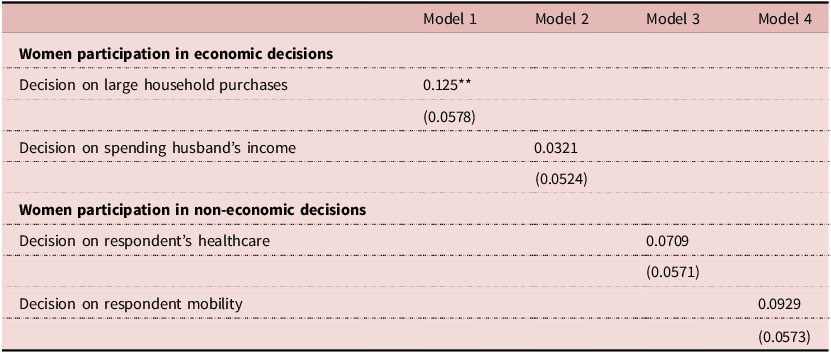

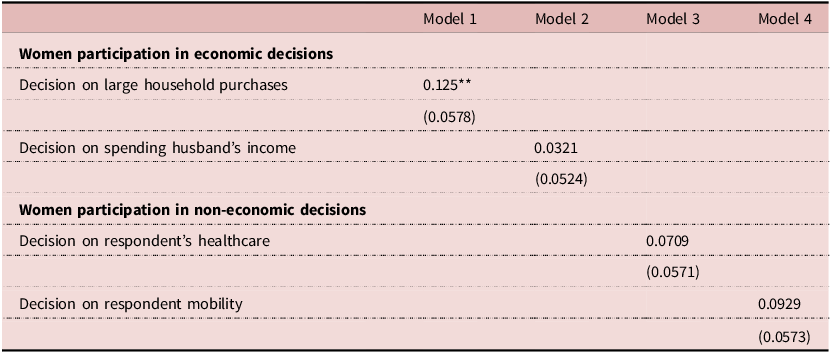

Sensitivity Analysis: To assess the sensitivity of women’s decision-making effect on child nutritional outcome, this study examines the association between categorical variables of both dimensions, economic as well as non-economic, of decision-making power and child HAZ. As presented in Table 4, the coefficients for all decisions are positively associated with child growth; however, only decision related to major household purchases is statistically significant at the 5%. More specifically, children of women who participate in decisions regarding major household purchases are predicted to have HAZ scores that are, 0.13 standard deviation higher than those whose mothers do not involve in such decisions.

Table 4. Maximum Likelihood Estimates of Height-for-Age z-Scores (0–5 years) by Different Types of Women’s Decisions

Source: Authors’ calculations using PDHS 2012-13, 2017-18. Standard errors are in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. All models were controlled for individual, household and community level variables. For detailed parameters see Table S2 in supplementary file.

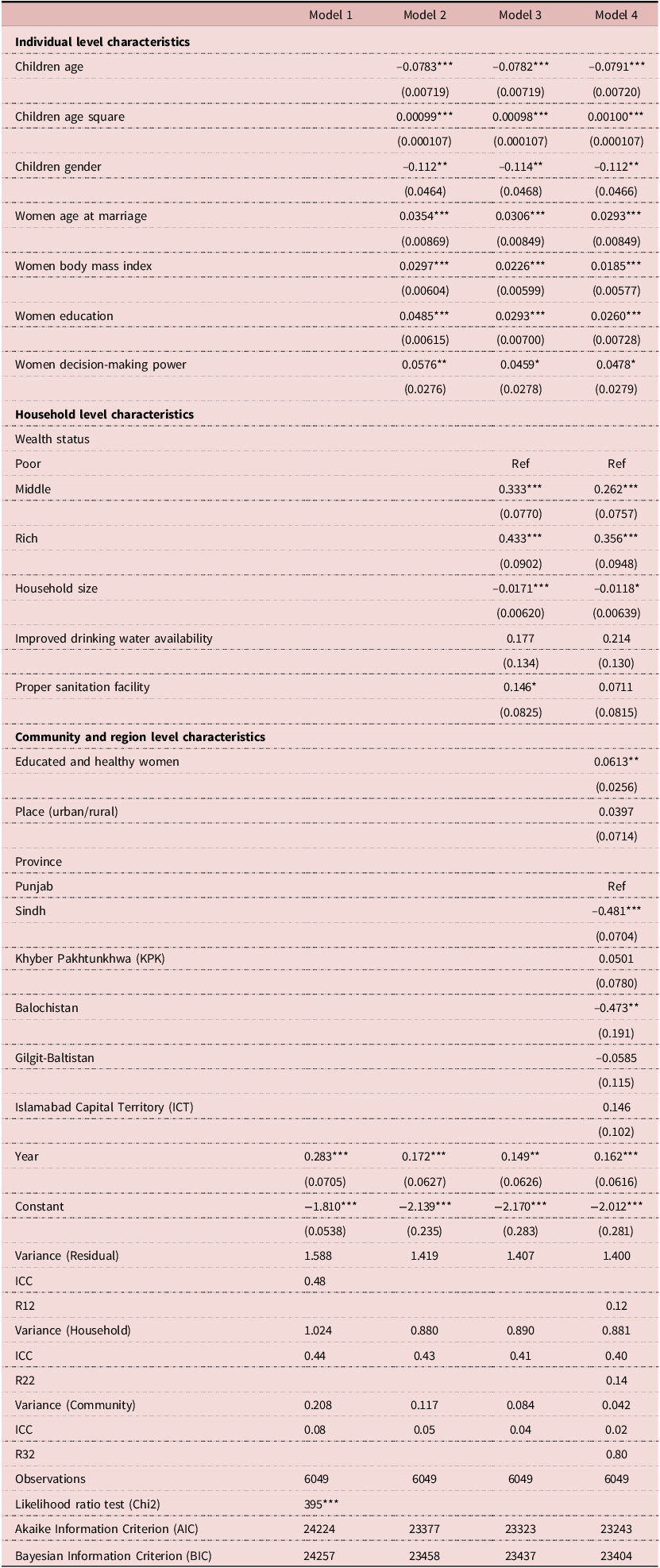

Robustness check

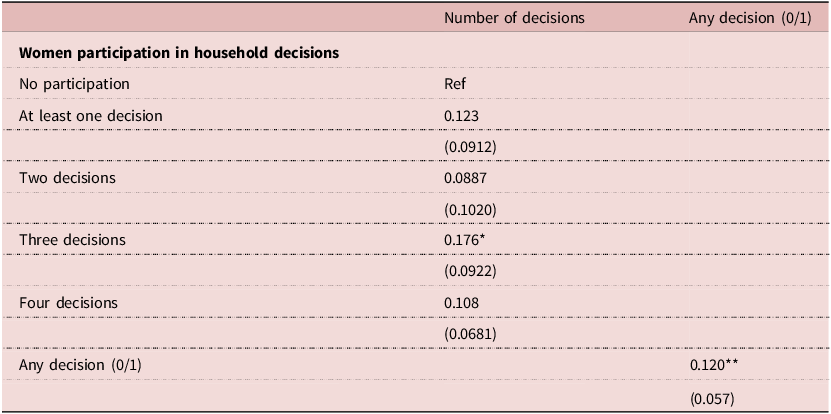

Two robustness checks were applied in this study to further affirm initial results (Table 5). First, the decision-making variable was defined in two different ways; where one categorized decision-making from low autonomy to high autonomy while second shows no participation vs participation in at least one decision. Results showed that compared to no participation, involvement in three decisions showed highest improvement in child stunting outcomes. As per second definition, compared to no participation, women’s participation in at least one decision improved child HAZ by 0.12 SD with the statistical significance of 5%. This exhibits that the positive association between women’ involvement in household decisions and child nutrition does not affect by how decision-making variable is defined. Secondly, two binary dependent variables were constructed; stunted and severely stunted, for which separate logistic regression models were estimated. Both models reaffirmed preliminary findings that women’s decision-making ability is positively influencing child nutritional status with stronger effect observed for severely stunted children (see Table S4 in supplementary file for details).

Table 5. Maximum Likelihood Estimates of Height-for-Age z-Scores (0–5 years) by Extent of Women’s Decision-Making Involvement

Source: Authors’ calculations using PDHS 2012–13, 2017–18. Standard errors are in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. All models were controlled for individual, household and community level variables. For detailed parameters see Table S3 in supplementary file.

Discussion

For the past two decades, the prevalence of child undernutrition has been steadily decreasing; however, a significant number of children continue to experience inadequate nutritional growth, which instigates further research on determinants of child nutritional status. The present study explores the association between women’s decision-making ability and childhood stunting by using a three-level hierarchical model. Findings from this study contribute to the rather scant literature on the role of women’s decision-making power for better child health outcomes in the context of Pakistan overtime. Regional analysis based on geographical locations were performed considering cultural and socioeconomic differences within country. In addition, separate role of economic as well as non-economic decisions were investigated following existing literature that a composite index may mask the individual effect of different decision-making dimensions.

It is evident from the findings of this study that women’s participation in household decisions significantly improve childhood stunting outcomes and has remained relatively stable overtime. The positive effects of women’s involvement in household decisions on child nutritional outcomes are consistent with existing literature from different countries (Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Kordas and Murray-Kolb2015; Onah et al. Reference Onah, Horton and Hoddinott2021; Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Saima and Goni2015). However, regional analysis revealed that this association is more pronounced in Sindh province than in other regions, highlighting that cultural norms and economic conditions mediate the effect of women’s decision-making power. One possible explanation can be that children in Sindh are comparatively vulnerable to stunted growth than some other provinces, suggesting that even modest changes in underlying factors such as women’s decision-making power could have substantial effect on nutritional outcomes. Another rationale of these findings can be that the interventions promoting women’s decision-making are more efficiently implemented in Sindh than other regions. These regional variations are consistent with findings from existing literature, which have also reported contradictory results within and across countries (Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Ruel, Ferguson and Uauy2015).

The sensitivity analysis revealed that although both economic and non-economic domains of decisions are positively associated with children’s long-term nutritional outcomes, only financial decision related to large household purchases was significant. These results support previous literature, which also indicate that different types of decisions influence child health indicators variably (Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Kordas and Murray-Kolb2015; Shroff et al. Reference Shroff, Griffiths, Suchindran, Nagalla, Vazir and Bentley2011). This may imply that non-financial decisions like mobility and health-care are relatively less constrained in the context of Pakistan, suggesting that women may face less barriers in accessing information or healthcare services. Another study from Pakistan also found no direct association between women’s mobility and child nutritional status (Shafiq et al. Reference Shafiq, Hussain, Asif, Hwang, Jameel and Kanwel2019). However, decisions related to purchases indicates greater control over household resources, which women can divert toward nutritious food, healthcare, safe drinking water and hygienic sanitation (Abate and Belachew Reference Abate and Belachew2017; Malapit et al. Reference Malapit, Kadiyala, Quisumbing, Cunningham and Tyagi2015; Quisumbing and Maluccio Reference Quisumbing and Maluccio2003). These findings support national social protection projects like Benazir Income Support program (BISP) which help women achieve autonomy and financial support, resulting into better child nutritional growth.

The findings further suggest that women formal education ensures better child Height-for-Age z-score. One existing study from Pakistan also indicated a positive association between women education and child health outcome (Aslam and Kingdon Reference Aslam and Kingdon2012). In line with existing evidence, present study also found that women’s nutritional status is positively associated with child nutritional growth (Haque et al. Reference Haque, Alam, Rahman, Mustafa, Ahammed, Ahmad, Hashmi, Wubishet and Keramat2022). Household level variates also found to be positively influencing child long term nutritional status especially economic status. The family wealth not only improves child health through nutrition availability but also helps to maintain optimal growth surroundings (Shahid et al. Reference Shahid, Ahmed, Ameer, Guo, Raza, Fatima and Qureshi2022). This study also found that family size is another critical determinant at household level which effect children normal growth. Existing studies also highlighted that larger family size leads to poor nutritional quality of available food which may affect child’s height and weight negatively (Feng and He Reference Feng and He2021). It is especially crucial from the context of Pakistan which is 5th most populous country according to population census-2017 (PBS 2017). It would be a challenging situation if not dealt with great concern, given the fact that economic growth is not progressing in parallel to population growth. Lastly, women’s education and access to health services at community level significantly improves child nutritional outcomes, as educated women are more likely to share knowledge about nutritious food and healthcare practices. This finding is consistent with existing research from Pakistan which also highlighted the significance of women education and availability of health facilities in a community to improve nutritional security (Ishfaq et al. Reference Ishfaq, Anjum, Kouser, Nightingale and Jepson2022).

The government of Pakistan has launched several projects to improve the nutritional status of children. For example, with the cooperation of the World Food Program, the ‘Scaling up Nutrition’ project in Balochistan Province aims to provide ready-to-eat nutritious food to target groups (WFP 2017). Similarly, the Reproductive Maternal Neonatal Child Health and Nutrition (IRMNCH&N) project provides micronutrients to stunted children and health awareness counselling sessions to mothers in Punjab Province (Malik Reference Malik2016). The provincial government of Sindh also provides high-nutritive-value food to children under the age five and pregnant nursing women who are food-insecure households (World Bank 2017). These nutrition-oriented policy interventions are important for addressing childhood nutrition problems in the short-term. However, addressing the problem of child undernutrition on a long-term basis requires more nuanced policy responses.

This study recommends that nutrition-oriented policies should also consider non-food factors such as health, education, the status of women and family planning. Although not examined in this study, prior research suggests that increasing the age at marriage leads to women having a greater role in household decision-making (Field and Ambrus Reference Field and Ambrus2008). Thus, one possible policy instrument to improve women’s decision making ability in Pakistan is to increase the minimum age at marriage. This will also bestow an opportunity for better educational achievements which not only provides access to better health care knowledge but also provides financial resources. Lastly, in addition to focusing on women to increase their participation in household decisions, it is equally crucial to engage their husbands and other family members. All stakeholders in women’s social circle contribute to enhance their status within household and society.

Limitations: Although, this study provides interesting insights, there are some unavoidable limitations. Firstly, the analysis relies on self-reporting data related to women’s decision-making variables, which may cause the risk of information bias due to subjective nature of questions. Secondly, the study design does not allow for the identification of the pathways or causal link between women’s decision-making ability and childhood stunting. Future research can focus on qualitative data for better questions related to specific cultural context and identification of underlying pathways particular to each region.

Conclusions

This study explores the association between women’s participation in household decision-making and childhood stunting over time. Estimates from multilevel model suggests a positive influence of women’s involvement in financial decisions for children’s long-term nutritional status, with no significant changes observed over the course of five years. Regional analysis highlights that children living in Sindh are more likely to benefit from women’s decision-making power compared to those in other regions. Based on these findings, this study recommends that policies and projects prioritize the enhancement of women’s capabilities particularly through improved education, health and decision-making power as a pathway toward achieving national nutrition goals.

Relevant organizations and policy makers should formulate multi-sectoral interventions to address childhood malnutrition, with consideration to the varying effect of women’s decision-making across different regional context. Finally, these measures together with focused public education campaigns on marriage age and family planning could contribute to a healthier, more nutritionally secure, and economically productive future generation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932025100448

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Muhammad Masood Azeem for insightful suggestions, which contributed greatly to improve the quality of paper. Authors also acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback and the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) Program for giving access to the datasets used in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.