Statement of Research Significance

Research Question(s) or Topic(s): This study investigated cognitive functioning in survivors of childhood and young adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated under a single protocol, focusing on performance across several cognitive domains and associations with clinical risk factors. Main Findings: Average performance was generally comparable to normative data but impairments were common, particularly in processing speed, executive functions, and working memory. Younger age at diagnosis was associated with poorer performance in processing speed, executive functions, and non-verbal reasoning, whereas hematopoietic stem cell transplantation was associated with poorer processing speed and non-verbal reasoning. Study Contributions: This study provides new evidence on long-term cognitive outcomes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors, indicating normal cognitive function on average, but a relatively high proportion of severely impaired participants. It identifies younger age at diagnosis and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as clinical risk factors, indicating the potential for risk-based cognitive monitoring and tailored survivorship care.

Introduction

The vast majority of children, adolescents, and young adults (CAYA) diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) now survive. Consequently, increasing attention is being paid to late effects, including cognitive impairment. Reported deficits most often affect processing speed, executive functions, and attention (Alias et al., Reference Alias, Mohd Ranai, Lau and de Sonneville2024; Godoy et al., Reference Godoy, Simionato, de Mello and Suchecki2020; Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Embry, Kairalla, Sharkey, Gioia, Griffin, Berger, Weisman, Noll and Winick2024; van der Plas, Modi, et al., Reference van der Plas, Modi, Li, Krull and Cheung2021; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhuang, Lin, Michelson and Zhang2020), which may hinder educational and professional achievement (Ahomäki et al., Reference Ahomäki, Harila-Saari, Matomäki and Lähteenmäki2017; Baughan et al., Reference Baughan, Pell, Mackay, Clark, King and Fleming2023; Baum et al., Reference Baum, Lax, Lehmann, Merkel-Jens, Beelen, Jöckel and Dührsen2023) and reduce quality of life (van der Plas, Spencer Noakes, et al., Reference van der Plas, Spencer Noakes, Butcher, Weksberg, Galin-Corini, Wanstall, Te, Hopf, Guger, Hitzler, Schachar, Ito and Nieman2021). A deeper understanding of these sequelae is important to guide screening, interventions, and survivor support (Elsbernd et al., Reference Elsbernd, Pedersen, Boisen, Midtgaard and Larsen2018; Krull et al., Reference Krull, Hardy, Kahalley, Schuitema and Kesler2018; van der Plas, Qiu, et al., Reference van der Plas, Qiu, Nieman, Yasui, Liu, DIxon, Kadan-Lottick, Weldon, Weil, Jacola, Gibson, Leisenring, Oeffinger, Hudson, Robison, Armstrong and Krull2021).

The neurotoxic burden of therapy has declined with the omission of cranial radiation from first-line treatment; however, intensive central nervous system (CNS)-directed chemotherapy remains a significant risk factor, and cognitive impairment continues to be reported in survivors treated with chemotherapy alone (Egset et al., Reference Egset, Stubberud, Ruud, Hjort, Eilertsen, Sund, Hjemdal, Weider and Reinfjell2024; Gandy et al., Reference Gandy, Scoggins, Jacola, Litten, Reddick and Krull2021; Lofstad et al., Reference Lofstad, Reinfjell, Weider, Diseth and Hestad2019; van der Plas, Spencer Noakes, et al., Reference van der Plas, Spencer Noakes, Butcher, Weksberg, Galin-Corini, Wanstall, Te, Hopf, Guger, Hitzler, Schachar, Ito and Nieman2021). Established clinical risk factors include young age at diagnosis (Jacola et al., Reference Jacola, Krull, Pui, Pei, Cheng, Reddick and Conklin2016; Mavrea et al., Reference Mavrea, Efthymiou, Katsibardi, Tsarouhas, Kanaka-Gantenbein, Spandidos, Chrousos, Kattamis and Bacopoulou2021; van der Plas, Qiu, et al., Reference van der Plas, Qiu, Nieman, Yasui, Liu, DIxon, Kadan-Lottick, Weldon, Weil, Jacola, Gibson, Leisenring, Oeffinger, Hudson, Robison, Armstrong and Krull2021), female sex (Gandy et al., Reference Gandy, Scoggins, Phillips, Van Der Plas, Fellah, Jacola, Pui, Hudson, Reddick, Sitaram and Krull2022; Jacola et al., Reference Jacola, Krull, Pui, Pei, Cheng, Reddick and Conklin2016; van der Plas, Qiu, et al., Reference van der Plas, Qiu, Nieman, Yasui, Liu, DIxon, Kadan-Lottick, Weldon, Weil, Jacola, Gibson, Leisenring, Oeffinger, Hudson, Robison, Armstrong and Krull2021), and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) treatment (Dreneva & Devyaterikova, Reference Dreneva and Devyaterikova2022; Gabriel et al., Reference Gabriel, Hoeben, Uhlving, Zajac-Spychala, Lawitschka, Bresters and Ifversen2021; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Sharafeldin, Rexer, Streck, Petersen, Henneghan and Kesler2021; Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Deal, Rosenstein, Quillen, Chien, Wood, Shea and Park2021). The patients requiring HSCT are at particularly high risk, as they typically undergo intensive chemotherapy regimens followed by myeloablative conditioning with high-dose chemotherapy and/or total body irradiation (Hoeben et al., Reference Hoeben, Pazos, Albert, Seravalli, Bosman, Losert, Boterberg, Manapov, Ospovat, Milla, Abakay, Engellau, Kos, Supiot, Bierings and Janssens2021). After transplantation, prolonged immunomodulatory therapy further increases the risk of neurotoxic side effects (Gabriel et al., Reference Gabriel, Hoeben, Uhlving, Zajac-Spychala, Lawitschka, Bresters and Ifversen2021). Acute treatment-related neurotoxic events, such as posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), seizures, and coma, are less well studied but may also be associated with poorer cognitive outcomes (Anastasopoulou et al., Reference Anastasopoulou, Eriksson, Heyman, Wang, Niinimäki, Mikkel, Vaitkevičienė, Johannsdottir, Myrberg, Jonsson, Als-Nielsen, Schmiegelow, Banerjee, Harila-Saari and Ranta2019; Nassar et al., Reference Nassar, Conklin, Zhou, Ashford, Reddick, Glass, Laningham, Jeha, Cheng and Pui2017; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Khan, Li, Mirzaei Salehabadi, Brinkman, Srivastava, Robison, Hudson, Krull and Sadighi2022). Time since treatment completion may also influence neurocognitive outcomes, although findings are mixed: some studies suggest recovery over time (Buizer et al., Reference Buizer, De Sonneville, Van Den Heuvel-Eibrink, Njiokiktjien and Veerman2005; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Cheung, Conklin, Jacola, Srivastava, Nolan, Zhang, Gurney, Huang, Robison, Pui, Hudson and Krull2018), whereas others indicate persistent or late-emerging deficits (Krull et al., Reference Krull, Brinkman, Li, Armstrong, Ness, Kumar Srivastava, Gurney, Kimberg, Krasin, Pui, Robison and Hudson2013).

To date, studies of neurocognitive outcomes following treatment for ALL have primarily focused on North American cohorts (Semendric et al., Reference Semendric, Barker, Haller, Pollock, Collins-Praino and Whittaker2025), which differ from Scandinavian cohorts in health culture, access to healthcare, and socioeconomic support systems – factors likely to influence long-term neurocognitive outcomes and their impact on everyday life. Our study addresses this gap in knowledge by examining a population-based cohort of CAYA treated for ALL in Eastern Denmark under the Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (NOPHO) ALL2008 protocol (Toft et al., Reference Toft, Birgens, Abrahamsson, Griškevičius, Hallböök, Heyman, Klausen, Jónsson, Palk, Pruunsild, Quist-Paulsen, Vaitkeviciene, Vettenranta, Asberg, Helt, Frandsen and Schmiegelow2016, Reference Toft, Birgens, Abrahamsson, Griškevic Ius, Hallböök, Heyman, Klausen, Jónsson, Palk, Pruunsild, Quist-Paulsen, Vaitkeviciene, Vettenranta, Åsberg, Frandsen, Marquart, Madsen, Norén-Nyström and Schmiegelow2018). The primary objective was to investigate neurocognitive performance among individuals treated for ALL, based on age-adjusted Z scores derived from normative data. Secondary objectives were to investigate associations between neurocognitive performance and age at diagnosis, sex, time since end of treatment, HSCT, and neurotoxic events (PRES, seizures, and coma) during treatment. We hypothesized that, on average, participants would perform below normative expectations in attention, executive functions, and working memory, and that younger age at diagnosis, female sex, and HSCT treatment would be associated with poorer cognitive outcomes. Associations with time since end of treatment and neurotoxic events during treatment were included as additional predictors, although prior evidence for these factors is limited.

Methods

Participants

This study was an add-on to the Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Survivor Toxicity And Rehabilitation (ALL-STAR) study, a Danish cohort study investigating late effects among CAYA individuals who survived ALL (Andrés-Jensen et al., Reference Andrés-Jensen, Skipper, Mielke Christensen, Hedegaard Johnsen, Aagaard Myhr, Kaj Fridh, Grell, Pedersen, Leisgaard Mørck Rubak, Ballegaard, Hørlyck, Beck Jensen, Lambine, Gjerum Nielsen, Tuckuviene, Skov Wehner, Klug Albertsen, Schmiegelow and Frandsen2021). Participants were treated according to the NOPHO ALL2008 protocol at Copenhagen University Hospital or Odense University Hospital between 2008 and 2021. The protocol excludes Philadelphia-positive ALL, infant ALL, and patients with Down syndrome (Toft et al., Reference Toft, Birgens, Abrahamsson, Griškevic Ius, Hallböök, Heyman, Klausen, Jónsson, Palk, Pruunsild, Quist-Paulsen, Vaitkeviciene, Vettenranta, Åsberg, Frandsen, Marquart, Madsen, Norén-Nyström and Schmiegelow2018). Eligibility criteria for the present study were: i) age at ALL diagnosis <25 years, ii) ≥ 1 year since end of ALL treatment, iii) age ≥ 7 years at time of cognitive evaluations, and iv) consent to participate in the ALL-STAR study at the Copenhagen University Hospital (Figure 1). Participants were excluded if they were not fluent in Danish, had a history of neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., Trisomy 21, infantile autism), or had brain injuries unrelated to cancer or cancer therapy, as determined by review of their medical records.

Figure 1. Recruitment, enrollment, and completion of study measures.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee for the Capital Region of Denmark (no. H-18035090, amendment 96042) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (no. P-2021-473) and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment. For participants younger than 15 years, consent was provided by their parents, and the participants gave verbal or informal assent. For participants aged 15–17.9 years, written informed consent was obtained from both the participant and their parents.

Setting

The ALL-STAR Study is coordinated by the Pediatric Oncology Laboratory at Copenhagen University Hospital. Neurocognitive testing was conducted between November 2021 and May 2023. Tests were administered by trained psychology students under the supervision of experienced neuropsychologists from both Copenhagen University Hospital and the Copenhagen Centre for Rehabilitation of Brain Injury. All assessments were performed in a quiet, uninterrupted setting. While testing was completed in a single session, short breaks were provided as needed to accommodate individual participants.

ALL-specific medical history and demographics

Patient demographics, treatment exposure, and prospectively recorded neurotoxicity data were retrieved from the NOPHO ALL2008 registry and verified against patient medical records. Additional demographic information was obtained via a brief questionnaire, which included the educational level and occupational situation of the participant and their parents, as well as the living situation and household income of the participant or their parents. Parental education was categorized according to the International Standard Classification of Education as basic, secondary, or tertiary education (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012).

Neurocognitive tests

Neurocognitive performance was assessed using a battery of standardized tests covering multiple cognitive domains. The assessment lasted approximately 90 minutes and included subtests from several instruments (detailed in Supplementary Table S1). If a test was not performed, the reason was recorded (Supplementary Table S2). The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fifth Edition (WISC-V; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2014) was administered to participants aged 7–15, and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2008) was used for those aged 16 and older. Processing speed was evaluated using the Coding and Symbol Search subtests from the WISC-V or the WAIS-IV. Executive functions, specifically cognitive flexibility, were assessed in participants aged 8 years and older using the Trail Making Test (TMT) from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS; Delis et al., Reference Delis, Kaplan and Kramer2001). Condition 4 (Number–Letter Switching) served as the primary outcome measure (TMT Switch). In addition, a Switching Contrast Score (Condition 4 minus the average of Conditions 2 and 3: Number Sequencing and Letter Sequencing) was calculated to control for component processes of sequencing and motor speed (TMT Contrast). Condition 1 (Visual Scanning) was included only to maintain standard test administration. Verbal reasoning and vocabulary were assessed with the Vocabulary and Similarities subtests from the WISC-V or WAIS-IV. Non-verbal reasoning was assessed with the Matrices and Figure Weights subtests from the WISC-V or WAIS-IV. Working memory was assessed with the Digit Span subtests from the WISC-V or WAIS-IV. Visuospatial and motor skills were assessed with the Block Design test from the WISC-V or WAIS-IV and Condition 5 of the TMT (Motor Speed; TMT Motor) from the D-KEFS, included only for participants aged 8 years and older. Sustained attention was assessed in participants aged 8 years and older using the Conners Continuous Performance Test–Third Edition (CPT-III; Conners, Reference Conners2014). The analysis included the following CPT-III outcome variables: Detectability (ability to discriminate between targets and non-targets), Omissions (inattention), Commissions (impulsivity), Hit Reaction Time (processing speed), and Variability (attention lapses). These variables were chosen because they are commonly reported in studies of attention and executive functions in ALL survivors (Fellah et al., Reference Fellah, Cheung, Scoggins, Zou, Sabin, Pui, Robison, Hudson, Ogg and Krull2019; Gandy et al., Reference Gandy, Sapkota, Scoggins, Jacola, Koscik, Hudson, Pui, Krull and Van Der Plas2023; Partanen et al., Reference Partanen, Phipps, Russell, Anghelescu, Wolf, Conklin, Krull, Inaba, Pui and Jacola2021) and are considered sensitive indicators of sustained attention and impulsivity (Conners, Reference Conners2014).

Statistical analysis

Participants were compared with eligible non-participants to assess potential selection bias. Continuous variables were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and total ranges and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages and compared using Fisher’s exact test.

All test scores were age-standardized using appropriate normative data prior to analysis. Wechsler subtests (WISC-V and WAIS-IV) were standardized using Danish-Norwegian-Swedish normative data (M = 10, SD = 3). D-KEFS subtests were standardized using U.S. normative data (M = 10, SD = 3). CPT-III scores were standardized using U.S. normative data (M = 50, SD = 10). To enable direct comparison across tests, all scores were transformed into Z scores by subtracting the normative mean and dividing by the normative SD for each measure. Additionally, the direction of the CPT-III scores was reversed so that higher Z scores represented better performance on all tests. Descriptive statistics for the Z score distributions were summarized as means with SDs and nominal 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Normality was assessed by visual inspection of Q–Q plots and histograms with normal curves, supplemented by Shapiro–Wilk tests. Variables with p < .05 in the Shapiro–Wilk test and clear deviations from normality in plots were classified as non-normal. For approximately normally distributed scores, one-sample Student’s t tests were used to compare participants’ mean Z scores with the normative mean of 0. For variables deviating from normality, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted. The test probabilities were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure. Claim of statistical significance required an FDR-corrected p value < .05.

In addition, we calculated the percentages of participants with Z scores at or below thresholds of ≤ −1.3 and ≤ −2. These thresholds are widely used as the operational definitions of mild and severe neurocognitive impairment (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Phillips, Liu, Ehrhardt, Bhakta, Brinkman, Williams, Yasui, Khan, Srivastava, Ness, Robison, Hudson and Krull2024; Gandy et al., Reference Gandy, Sapkota, Scoggins, Jacola, Koscik, Hudson, Pui, Krull and Van Der Plas2023; van der Plas, et al., Reference van der Plas, Qiu, Nieman, Yasui, Liu, DIxon, Kadan-Lottick, Weldon, Weil, Jacola, Gibson, Leisenring, Oeffinger, Hudson, Robison, Armstrong and Krull2021). Percentages were presented with exact 95% CIs. To summarize impairment across domains, participants were classified as impaired within a domain if at least one test score in that domain met the threshold (≤ –1.3 or ≤ −2.0). For each threshold, we calculated the proportion of participants with impairment in at least one domain and in two or more domains, using exact 95% CIs.

We evaluated the associations between cognitive Z scores and five predictors: age at diagnosis (per 10 years), sex (reference = female), time since the end of treatment (per 5 years), HSCT treatment (reference = no), and the presence of at least one major neurotoxic event during treatment (reference = no). Multiple linear regression models were fitted for each cognitive outcome, with all predictors entered simultaneously to estimate their mutually adjusted effects. Regression coefficients, nominal 95% CIs, and FDR-corrected p values were reported. The FDR correction was applied to the p values across all cognitive outcomes, separately for each predictor, with statistical significance defined as p < .05. In addition to the mutually adjusted models, univariate models were also fitted.

Parental tertiary education (yes/no) was initially considered based on its association with cognitive outcomes in both childhood cancer survivors and the general population (Eilertsen et al., Reference Eilertsen, Thorsen, Holm, Bøe, Sørensen and Lundervold2016). In our data, parental education was not significantly related to the primary predictors and did not materially alter the regression estimates. To avoid adjusting for variables lacking confounding influence, parental education was excluded from the final analyses.

Missing data were rare and mainly due to practical constraints (e.g., unavailable materials, administration errors, scheduling issues); less commonly, scores were missing due to participant fatigue or task-related difficulties. Missing values were not imputed in the primary analyses. For most outcomes, this corresponds to assuming that data were missing at random. However, when summarizing impairment, this approach treats missing test results as not impaired. Because this may underestimate impairment in cases where missingness reflected fatigue or difficulties, we conducted conservative robustness analyses in which such cases were imputed as the lowest observed score for that test when computing means, CIs, and SDs. These imputed scores were then evaluated using the standard impairment thresholds (Z ≤ −1.3 and Z ≤ −2) to estimate impairment prevalence.

The study used a convenience sample size determined by feasibility and constrained by the number of eligible patients in long-term follow-up. No formal sensitivity or power analyses were conducted.

To visualize patterns for the individual cognitive profiles, hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance, complete linkage) was applied to the matrix of cognitive Z scores using the R package ComplexHeatmap v2.20.0 (Gu, Reference Gu2023). This approach orders participants by the similarity of their cognitive profiles, producing a dendrogram and heatmap that visually highlight different patterns for the performance across all cognitive tests. The visualization was used descriptively to illustrate different patterns, not to define clinical subgroups.

All data handling, visualizations, and statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.2; R Core Team, 2024).

Results

Participant characteristics

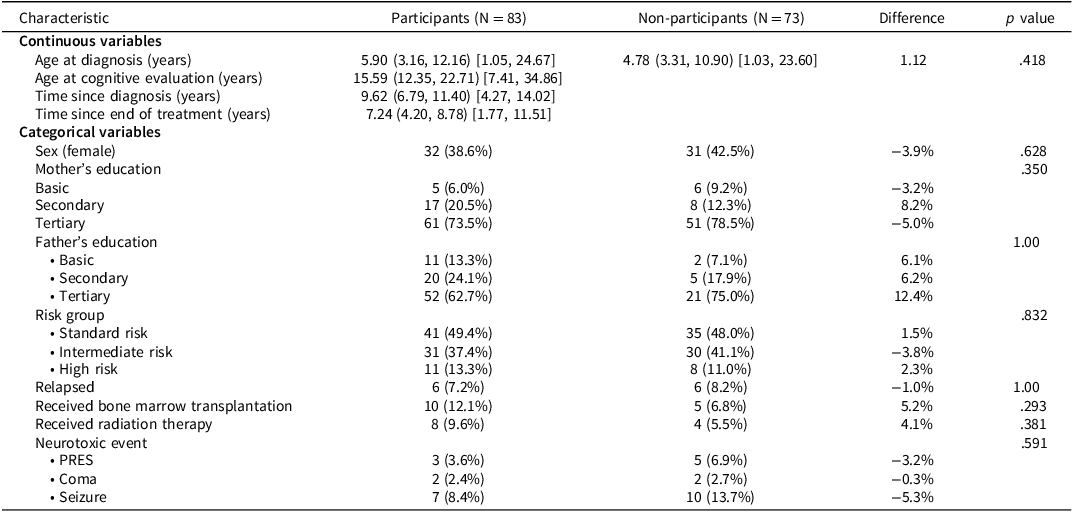

Of 163 potentially eligible survivors of ALL treated under the NOPHO ALL 2008 protocol in Eastern Denmark, 7 were excluded before recruitment: 3 due to pre-leukemic severe intellectual disability, 1 due to post-leukemic severe intellectual and physical disability, and 3 due to lack of fluency in Danish or residence outside Denmark. Among the remaining 156 eligible participants, 83 participated (participation rate = 53.2%; Figure 1). Of the 73 non-participants, 52 actively declined, 10 passively declined, 8 could not be reached, and 3 withdrew or failed to attend. One additional survivor was excluded prior to recruitment due to severe acquired brain injury and physical disability following ALL treatment. Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics, including neurotoxic events, for both participants and non-participants, who were similar across all the evaluated characteristics.

Table 1. Participant and non-participant characteristics

Note: Continuous variables are presented as median (IQR) [range], and categorical variables as N (%). Differences are reported as median differences for continuous variables and percentage point differences for categorical variables. p values are from Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range, PRES = posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Neurocognitive scores

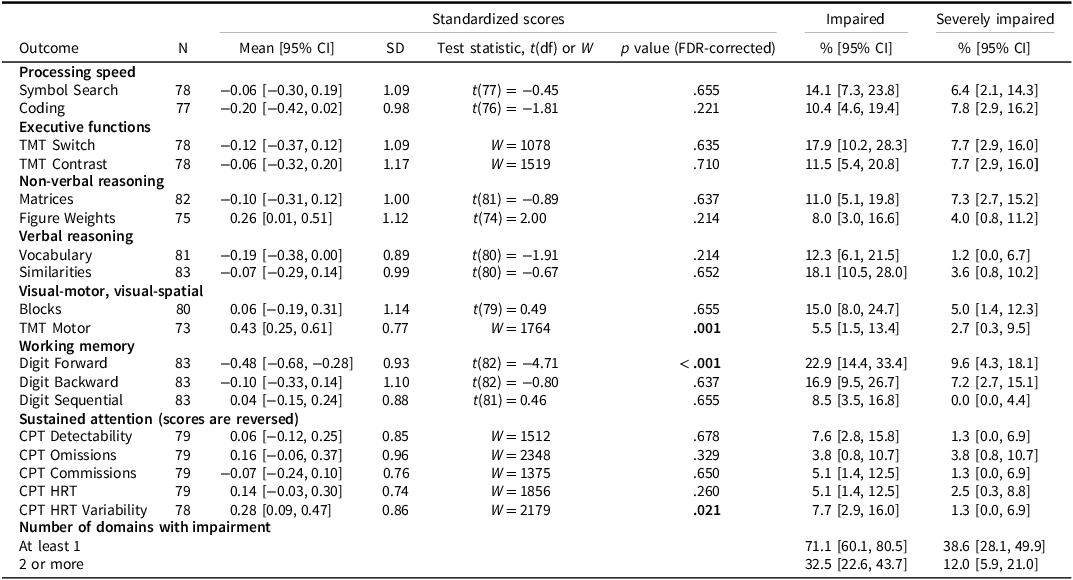

All participants underwent neurocognitive assessment. Missing data were uncommon and mostly due to administrative errors or unavailable materials; details are provided in Supplementary Materials (Table S2). Two participants were younger than 8 years and were therefore not included in the TMT and CPT-III outcomes. Six participants were unable to complete the Figure Weights subtest due to fatigue or task-related difficulties, and for other tests, between zero and two participants had missing data for the same reasons. Across most measures, we could not show that the mean Z scores differed from the normative mean of 0, as shown by the one-sample t tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (Table 2), and all mean scores were within ±0.5. Participants scored lower on Digit Forward, suggesting potential difficulties with attention span and working memory, whereas higher average scores were observed on TMT Motor and CPT-III HRT Variability, though the robustness analyses indicated that the higher average score in CPT-III HRT Variability may be due to the exclusion of participants with fatigue/difficulties (Supplementary Table S3). The boxplot (Figure 2) illustrates the distributions and outliers across tests, consistent with the t test results.

Figure 2. Boxplot of Z scores for each cognitive test. Boxes show the median and interquartile range. Whiskers extend from the hinge to the largest and smallest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range, with points beyond them depicted as outliers. Horizontal dotted reference lines indicate Z = 0 (normative mean), Z = –1.3 (impairment threshold), and Z = –2.0 (severe impairment). Abbreviations: CPT = Conners Continuous Performance Test, HRT = Hit Reaction Time, TMT = Trail Making Test.

Table 2. ALL participants’ performance on the neurocognitive tests with one-sample tests comparing to the normal population. Standardized scores according to the normative population and proportions with Z scores ≤ −1.3 (impaired) and ≤ −2 (severely impaired), respectively, are presented

Note: The table shows mean and standard deviation (SD) with nominal 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and false discovery rate (FDR) –corrected p values. Impaired indicates proportion scoring below Z ≤ −1.3 (≈10th percentile); Severely impaired indicates proportion scoring below Z ≤ −2 (≈2.3rd percentile). Adjusted p values are from two–sided one-sample t tests evaluating whether the mean differed from zero; for skewed distributions, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (W) were used instead. Values in bold indicate p < .05 and confidence intervals that do not include the theoretical impairment threshold.

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, CPT = Conners Continuous Performance Test, df = degrees of freedom, FDR = False discovery rate, HRT = Hit Reaction Time, SD = standard deviation, TMT = Trail Making Test.

Across tests (Table 2), the proportion of participants classified as impaired (Z ≤ −1.3) ranged from 3.8% to 22.9%. The prevalence of severe impairment (Z ≤ −2) ranged from 0% to 9.6% across tests. The prevalence of impairment on Digit Forward was particularly high (impaired: 22.9%, 95% CI [15.2, 33.0]; severely impaired: 9.6%, 95% CI [4.3, 18.1]).

At the domain level, 71.1% of participants showed impairment (Z ≤ −1.3) in at least one domain, 32.5% were impaired in two or more domains. Using the stricter threshold (Z ≤ −2), 38.6% had severe impairment in at least one domain, 12.0% in two or more domains. The robustness evaluation using imputed scores indicated that up to 42.2% had severe impairment in at least one domain and up to 13.3% in two or more domains, representing a relative increase of approximately 10% in impairment prevalence (Supplementary Table S3).

The heatmap visualization of individual Z scores (Figure 3) illustrates patterns of cognitive performance across participants. The top part of Figure 3 shows participants with low performance (dark colors) across most tests and for several domains. The middle part includes participants with more variable performance, characterized by very low scores on some measures (Z ≤ −2, dark purple) and average or higher scores on others (Z ≥ 0, yellow-green to yellow). The lower part, representing the largest group, includes participants who generally performed within or above the average range (Z > −1; green to yellow). As described in the Methods, the cluster structure should be interpreted cautiously and does not represent distinct clinical groups.

Figure 3. Heatmap of neurocognitive participant Z scores organized by their cluster assignments. Darker indicates lower scores, brighter indicates higher scores, grey is missing data. Abbreviations: CPT = Conners Continuous Performance Test, HRT = Hit Reaction Time, TMT = Trail Making Test.

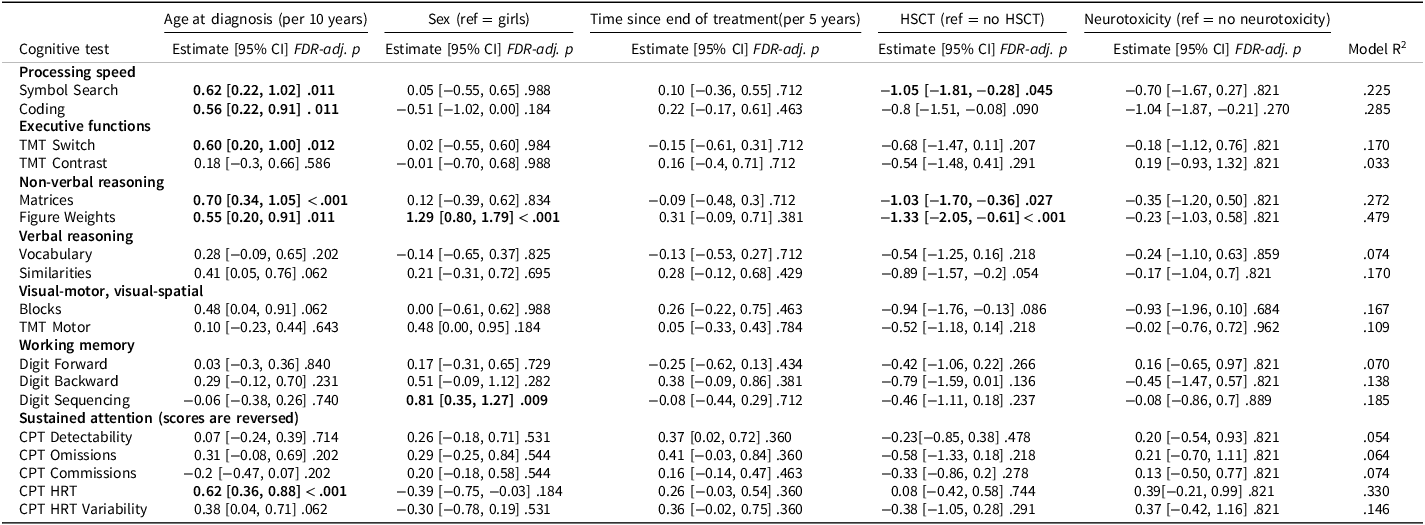

Regression analyses

The associations with age at diagnosis, sex, time since end of treatment, HSCT, and neurotoxicity were investigated in mutually adjusted linear regression models (Table 3; Figure 4) supplemented by univariate analyses (Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 4. Mutually adjusted linear regression analysis. Unstandardized estimates with 95% confidence intervals are shown for each predictor across cognitive outcomes. Predictors with FDR-adjusted p values < .05 are marked with *. Abbreviations: CPT = Conners Continuous Performance Test, HRT = Hit Reaction Time, TMT = Trail Making Test.

Table 3. Mutually adjusted regression analysis

Note: Linear regression was conducted to test for associations between cognitive test Z scores and age at diagnosis, sex, time since the end of treatment, HSCT, and major neurotoxic events (yes/no). Unstandardized regression coefficients, nominal 95% CIs, and p values are reported. To control for multiple comparisons, FDR correction was applied separately for each predictor across all cognitive outcomes; adjusted p values <0.05 are shown in bold.

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, CPT = Conners Continuous Performance Test, FDR = false discovery rate, HRT = Hit Reaction Time, HSCT = hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, TMT = Trail Making Test.

Higher age at diagnosis was associated with better performance on six of the 18 cognitive outcomes including processing speed (Coding, Symbol Search), executive functions (TMT Switch), non-verbal reasoning (Matrices, Figure Weights), and sustained attention (CPT HRT). For all remaining outcomes except CPT Commissions, the wide CIs indicated that a meaningful association with age at diagnosis could neither be confirmed nor rejected.

Male sex was associated with higher scores on non-verbal reasoning (Figure Weights) and working memory (Digit Sequencing). For several additional tests (Coding, CPT HRT, CPT HRT Variability), the upper confidence limits were <0.25, indicating that any potential male advantage on these outcomes would be small. For the remaining outcomes, CIs included both positive and negative values, suggesting that sex differences could neither be confirmed nor rejected (Table 3; Figure 4).

Time since end of treatment was not significantly associated with cognitive performance. CIs were wide for several outcomes, indicating considerable uncertainty and compatibility with moderate to large associations in either direction.

Participants who had undergone HSCT performed significantly worse on processing speed (Symbol Search) and non-verbal reasoning (Matrices and Figure Weights). Across all outcomes, 17 of 18 estimates were negative, and lower confidence limits were below −1 for 15 of the 18 outcomes, indicating that large adverse effects of HSCT could not be rejected. Because all HSCT participants in this sample were male, the adjusted associations reflect association of HSCT among male participants, whereas the univariate analyses compare male participants who received HSCT with the broader non-HSCT group (Supplementary Table S4).

Neurotoxicity was not significantly associated with performance in the adjusted analyses. However, the lower confidence limit was below −0.75 for most outcomes, suggesting that moderate to large adverse effects could not be rejected.

Discussion

We investigated neurocognitive functioning in a cross-sectional cohort of CAYA survivors of ALL treated under the same protocol. Standardized scores relative to normative data were used to characterize average performance, impairment prevalence, and associations with age at diagnosis, sex, time since end of treatment, HSCT, and treatment-related neurotoxicity.

Contrary to expectations, average performance was not clearly lower than in the normative population in domains such as attention, executive functions, and processing speed (Alias et al., Reference Alias, Mohd Ranai, Lau and de Sonneville2024; Fraley et al., Reference Fraley, Neiman, Feddersen, James, Jones, Mikkelsen, Nuss, Schlenz, Winters, Green and Compas2023; Gandy et al., Reference Gandy, Sapkota, Scoggins, Jacola, Koscik, Hudson, Pui, Krull and Van Der Plas2023; Godoy et al., Reference Godoy, Simionato, de Mello and Suchecki2020; van der Plas, Modi, et al., Reference van der Plas, Modi, Li, Krull and Cheung2021; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhuang, Lin, Michelson and Zhang2020). For some measures, average performance was above normative expectations, including faster TMT Motor Speed and lower CPT HRT Variability. However, these measures primarily reflect basic motor or response characteristics rather than higher-order cognitive processes.

The unexpectedly high average cognitive performance in our cohort may partly reflect selection bias toward higher-functioning or more motivated individuals, potentially reinforced by the cohort’s relatively high parental education level, as well as coming from families with greater socioeconomic resources. Among participants, 73.5% of mothers and 62.0% of fathers held tertiary education, compared with 42% of Danish adults aged 30–69 years at the time of the study (Danmarks Statistik, 2023). Although parental education did not differ significantly between participants and non-participants, recruitment from the ALL-STAR survivorship cohort (Andrés-Jensen et al., Reference Andrés-Jensen, Skipper, Mielke Christensen, Hedegaard Johnsen, Aagaard Myhr, Kaj Fridh, Grell, Pedersen, Leisgaard Mørck Rubak, Ballegaard, Hørlyck, Beck Jensen, Lambine, Gjerum Nielsen, Tuckuviene, Skov Wehner, Klug Albertsen, Schmiegelow and Frandsen2021), which required completing multiple questionnaires and a full day of clinical assessments, may have favored participation by families with higher education levels and greater resources. Consequently, our results may underestimate the cognitive difficulties in the broader survivor population. In addition, normative populations may underestimate the performance of healthy control groups. North American studies have reported WISC index and full-scale IQ scores near the normative average but still below those of a healthy control group, whose scores tended to be slightly above norms (van der Plas, Modi, et al., 2021). Thus, the use of normative scores may overestimate how well our participants perform relatively to healthy subjects.

Focusing on average performance may overlook that a considerable number of survivors experience marked cognitive difficulties. In this cohort, a clinically meaningful proportion of participants showed impairments or severe impairments, underscoring the presence of particularly vulnerable individuals. The prevalence of severe impairment was especially high in working memory (Digit Forward). Although overall cohort averages were generally comparable to normative data, a notable proportion of the participants showed severe impairment across multiple cognitive domains. The heatmap visualization of individual scores highlighted that, while many performed within the normative range across most domains, some showed severe difficulties across several domains. Quantitively, at least 71.1% of participants showed impairment in at least one domain and at least 32.5% showed impairment in two or more domains. Severe impairment was present in at least 38.6% of participants in one or more domains and at least 12.0% in two or more domains. Hence, a substantial number of participants exhibited some cognitive difficulties, and a smaller group showed multi-domain and severe impairments. In addition, one eligible survivor was not recruited due to severe acquired brain injury and physical disability following ALL treatment, and our robustness analyses indicated a relative increase of approximately 10% in the estimated prevalence of severe impairment. Together with the potential selection bias, these findings suggest that the true prevalence of cognitive deficits in the broader survivor population is likely underestimated.

Our results should also be interpreted in relation to international findings. Much of the existing evidence comes from large U.S. cohorts such as the St Jude Lifetime Cohort (Krull et al., Reference Krull, Brinkman, Li, Armstrong, Ness, Kumar Srivastava, Gurney, Kimberg, Krasin, Pui, Robison and Hudson2013), which differ from Scandinavian settings in socioeconomic conditions, healthcare access, and lifestyle risk factors associated with neurocognitive outcomes (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Stratton, Williams, Ahles, Ness, Cohen, Edelstein, Yasui, Oeffinger, Chow, Howell, Robison, Armstrong, Leisenring and Krull2023). Our study shows that even in our tax-funded healthcare system with relatively uniform access to services, the impairment prevalence suggested that the risk of clinically meaningful neurocognitive difficulties remains substantial.

Our results align with some recent studies showing that reliance on average performance can mask individual vulnerabilities. For instance, a Scandinavian study of adult survivors treated primarily according to NOPHO protocols reported averages near the normative expectations, yet 24−36% performed below −1.5 SD in executive functions, attention, and processing speed (Egset et al., Reference Egset, Stubberud, Ruud, Hjort, Eilertsen, Sund, Hjemdal, Weider and Reinfjell2024). Similarly, a study of survivors treated between 2000 and 2010 showed higher impairment prevalences on specific subtests of working memory and executive functions (i.e., Wechsler Digit Span and D-KEFS TMT), while most other tests were comparable to norms (Gandy et al., Reference Gandy, Sapkota, Scoggins, Jacola, Koscik, Hudson, Pui, Krull and Van Der Plas2023). Other research has also shown increased impairment prevalence in working memory and executive functions (i.e., Wechsler Digit Span and D-KEFS Verbal Fluency) (Mochon et al., Reference Mochon, Lippé, Krajinovic, Laverdière, Marjerrison, Michon, Robaey, Rondeau, Sinnett and Sultan2023). Survivor heterogeneity has been further highlighted in latent class analysis studies, which have identified distinct neurocognitive phenotypes within this population (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Phillips, Liu, Ehrhardt, Bhakta, Brinkman, Williams, Yasui, Khan, Srivastava, Ness, Robison, Hudson and Krull2024; Partanen et al., Reference Partanen, Phipps, Russell, Anghelescu, Wolf, Conklin, Krull, Inaba, Pui and Jacola2021).

In the multiple regression analysis mutually adjusting for age at diagnosis, sex, time since end of treatment, HSCT, and neurotoxic events during treatment, we found that younger age at diagnosis and HSCT treatment were associated with poorer neurocognitive performance. Younger age at diagnosis was associated with poorer processing speed, executive functions, non-verbal reasoning, and one of the measures of sustained attention, consistent with several previous studies (Krull et al., Reference Krull, Hardy, Kahalley, Schuitema and Kesler2018; van der Plas, Modi, et al., Reference van der Plas, Modi, Li, Krull and Cheung2021). For the remaining outcomes, CIs were wide, indicating that age-related effects could not be rejected.

HSCT was associated with poorer processing speed and non-verbal reasoning performance, aligning with studies reporting that up to a quarter of pediatric HSCT recipients develop neurocognitive sequelae (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Krull, Cushing-Haugen, Ullrich, Kadan-Lottick, Lee and Chow2022). Although only a few estimates reached statistical significance, most effects in our sample were adverse, and several confidence intervals included values consistent with large adverse effects. Because HSCT is typically reserved for more severe cases, the association with HSCT cannot be assumed to reflect treatment effects independent of disease characteristics. Additional clinical factors, such as CNS involvement or treatment complications, may contribute to both treatment decisions and neurocognitive outcomes, limiting the extent to which treatment-specific effects can be isolated.

Sex differences were observed only on a few measures. Male participants performed better on non-verbal reasoning (Figure Weights) and working memory (Digit Sequencing). Previous studies have suggested that female sex may be associated with poorer cognitive outcomes in ALL survivors (Gandy et al., Reference Gandy, Scoggins, Phillips, Van Der Plas, Fellah, Jacola, Pui, Hudson, Reddick, Sitaram and Krull2022; Krull et al., Reference Krull, Brinkman, Li, Armstrong, Ness, Kumar Srivastava, Gurney, Kimberg, Krasin, Pui, Robison and Hudson2013; van der Plas, Qiu, et al., Reference van der Plas, Qiu, Nieman, Yasui, Liu, DIxon, Kadan-Lottick, Weldon, Weil, Jacola, Gibson, Leisenring, Oeffinger, Hudson, Robison, Armstrong and Krull2021), and though our data did not always consistently reproduce that pattern, the uncertainty around many estimates means that disadvantages in female survivors cannot be rejected. Interpretation is further complicated by the lack of sex-stratified normative data, making it unclear whether observed differences reflect treatment effects, population-level sex differences, or measurement limitations.

We found no statistically significant association between neurotoxicity and neurocognitive outcomes. However, several estimates were compatible with potentially large adverse effects, and wide confidence intervals across multiple domains indicate that meaningful neurotoxic impacts cannot be rejected. Therefore, our study could not document an effect of neurotoxicity, nor could it exclude a major harmful effect.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is a cohort of ALL survivors treated under a uniform protocol and assessed with a broad neurocognitive battery covering attention, executive functions, processing speed, working memory, visuospatial and motor skills, verbal reasoning, and non-verbal reasoning.

However, several limitations should be noted. The reliance on standardizing to normative data rather than comparing with a control group, the limited statistical power, and the cross-sectional design constrain the generalizability and prevent the ability to draw longitudinal inferences. The small number of participants with HSCT and neurotoxicity reduced the power to detect or rule out related cognitive effects. The proportion participating was relatively low (53.2%), and as the participants had already completed the ALL-STAR survivorship study (Andrés-Jensen et al., Reference Andrés-Jensen, Skipper, Mielke Christensen, Hedegaard Johnsen, Aagaard Myhr, Kaj Fridh, Grell, Pedersen, Leisgaard Mørck Rubak, Ballegaard, Hørlyck, Beck Jensen, Lambine, Gjerum Nielsen, Tuckuviene, Skov Wehner, Klug Albertsen, Schmiegelow and Frandsen2021), selection bias is possible, potentially favoring healthier individuals, although those with poorer cognitive skills may also have been motivated by the opportunity for a detailed assessment. The battery did not cover all relevant domains; verbal reasoning was included, but comprehension, naming, and dedicated measures of learning and episodic memory were absent. Additionally, we did not include clinical factors such as sepsis (Partanen et al., Reference Partanen, Phipps, Russell, Anghelescu, Wolf, Conklin, Krull, Inaba, Pui and Jacola2021), fatigue (Egset et al., Reference Egset, Stubberud, Ruud, Hjort, Eilertsen, Sund, Hjemdal, Weider and Reinfjell2024; Vasquez et al., Reference Vasquez, Escalante, Raghubar, Kahalley, Taylor, Moore, Hockenberry, Scheurer and Brown2022), and pain (Partanen et al., Reference Partanen, Alberts, Conklin, Krull, Pui, Anghelescu and Jacola2022) in the analysis.

Clinical implications

International guidelines, including those from the Children’s Oncology Group (DeVine et al., Reference DeVine, Landier, Hudson, Constine, Bhatia, Armenian, Gramatges, Chow, Friedman and Ehrhardt2025), recommend neuropsychological evaluations for patients treated with CNS-directed therapies. Such evaluations should be performed at baseline, during long-term follow-up, and when clinical symptoms or academic difficulties arise. Similar recommendations are provided in the Psychosocial Standards of Care Project for Childhood Cancer (Annett et al., Reference Annett, Patel and Phipps2015) which emphasize risk-stratified cognitive follow-up for survivors exposed to treatments such as cranial irradiation and intrathecal chemotherapy. Our findings underscore the importance of adhering to these guidelines, particularly for survivors treated at a young age and those treated with HSCT, as these groups appear especially vulnerable to cognitive impairment and may require close monitoring and additional support.

Neurocognitive monitoring could be implemented using a brief screening protocol to identify survivors facing the most significant cognitive challenges. To facilitate feasible implementation in clinical settings, tiered models for neurocognitive follow-up have been proposed (Jacola et al., Reference Jacola, Partanen, Lemiere, Hudson and Thomas2021; Limond et al., Reference Limond, Bull, Calaminus, Kennedy, Spoudeas and Chevignard2015). The core battery proposed by Limond et al., is relatively brief and developmentally appropriate, covering the domains most affected in our cohort, including processing speed, executive functioning, and reasoning. Although originally developed for brain tumor survivors, the battery is efficient to administer and can be extended when clinically indicated, making it a strong candidate for broader implementation across diagnostic groups, including childhood ALL.

Finally, further efforts are needed to explore the potential for mitigating cognitive impairment. Some survivors in our cohort may have benefited from social and educational interventions available only in Denmark (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Larsen, Pouplier, Schmidt-Andersen, Thorsteinsson, Schmiegelow and Fridh2022; Thorsteinsson et al., Reference Thorsteinsson, Helms, Adamsen, Andersen, Andersen, Christensen, Hasle, Heilmann, Hejgaard, Johansen, Madsen, Madsen, Simovska, Strange, Thing, Wehner, Schmiegelow and Larsen2013), although their impact on cognitive outcomes remains to be formally investigated.

Conclusion

Although average cognitive performance among survivors of ALL was largely comparable to normative expectations, a notable proportion showed severe impairments across multiple domains. Younger age at diagnosis and HSCT were associated with poorer outcomes, highlighting key clinical risk factors to consider in cognitive monitoring and survivor care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617726101829.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marie Linneberg, Astrid Vestereng, and Sofie Ølgod for their valuable contributions to the neurocognitive assessments, and Vibeke Dam and Carsten Lose for their expertise and support in test administration and interpretation. We are also grateful for the support of the ALL-STAR team, in particular Sisse Høilund Carlsen for retrieval of clinical and demographic data.

Funding statement

This work has been supported by the Danish Childhood Cancer Foundation (grant number 2020-6785; Grant number 2021-7442), the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant number NNF21OC0072440), the Danish Cancer Society (grant number R260-A15221), and Helsefonden (grant number 18-B-0276). ITO was funded by the Swedish Childhood Cancer Fund (grant number FT2023-007).

Competing interests

Nothing to disclose.

Role of the funders

The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.