Summary

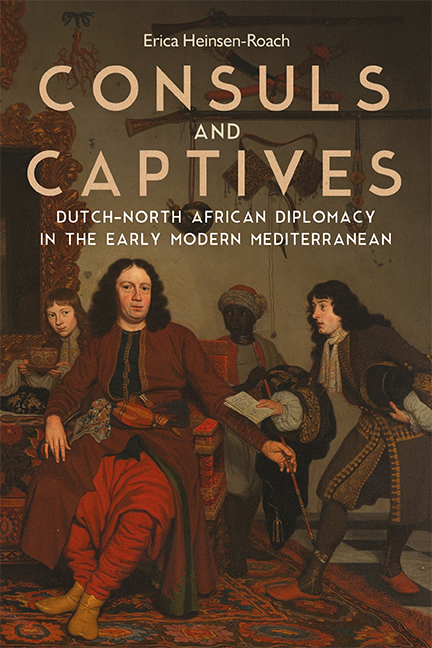

In the early 1900s, the Dutch author Louis Couperus strolled “in sheer romanticism” through the rue des Consuls in Algiers where, he claimed, all European consuls had resided during the town's golden age as a pirate republic. Couperus's seventeenth-century compatriots—regents, consuls, and captives alike—did not all share his sentiments. In 1691, the Dutch consul Zacharias Cousart referred to Tripoli as the “most miserable place under the sun.” A few years earlier, he had ransomed six Dutch captives but was never reimbursed. In fact, he never received compensation for at least three years of work, hampering his ability to give gifts and facilitate his negotiating position. Some years earlier, Ambassador Thomas Hees took a stroll up the river outside town, caught a pike, and to his own amusement, fell into the water, getting wet from the waist down. Hees's self-depreciating humor was a character trait but also a reminder that state representatives experienced life and work in the Maghrib differently. Hees, in his rank of ambassador, was treated with great respect and courtesy. The gifts Michiel Musscher so beautifully painted in Hees's portrait reflect the generosity that Maghribi officials showed foreign ambassadors. The position of Cousart and his peers differed. Consuls enjoyed many privileges and rights in their capacity as representatives of the state yet as foreign residents in town were also subject to Islamic law and local customary practices if they became embroiled in disputes with Muslim subjects. Personal debt, partly accrued by poor financing, and the escapes of slaves often put consuls in precarious situations, frustrating their ability to fulfill their tasks. Real problems left little room for romantic feelings.

We might therefore say that Christian consuls stationed in the Maghrib had a thankless position that resembles what the diplomatic historian D. C. M. Platt once called the “Cinderella” service, a term that described the disparagements that British consuls experienced during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. During the early modern period, the difference between consuls in continental Europe, who were “merely” responsible for commerce, and ambassadors involved in the grand scheme of European politics reflected a similar social discrepancy where consuls were not even regarded as belonging to the diplomatic world. The professionalization of the European consular corps in the twentieth century seems, therefore, the inevitable outcome of a long process of reconciling the tasks of consuls and ambassadors.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Consuls and CaptivesDutch-North African Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean, pp. 179 - 186Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019