Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Subjectivity in Troubadour Poetry

- Part II The ‘Chansons de geste’ in the Age of Romance: Political Fictions

- Part III Courtly Contradictions: The Emergence of the Literary Object in the Twelfth Century

- Part IV The Place of Thought: The Complexity of One in French Didactic Literature

- Part V Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry

- Part VI Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries

- Afterword

- General Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- Bibliography of Work by Sarah Kay

- Index

- Gallica

The Disembodied Tongue; or, The Place of the Book in the Livre de la Cité des Dames

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

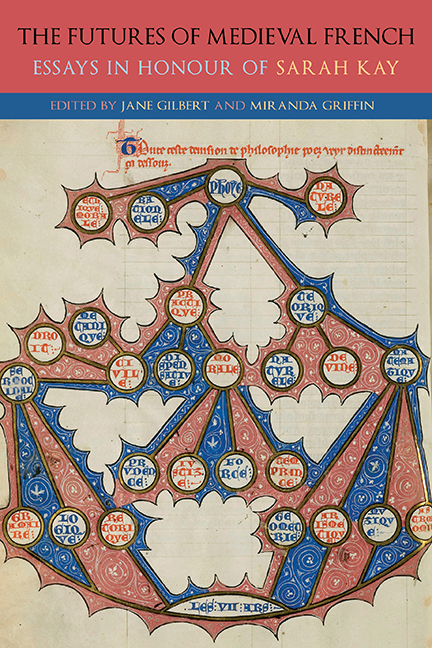

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Subjectivity in Troubadour Poetry

- Part II The ‘Chansons de geste’ in the Age of Romance: Political Fictions

- Part III Courtly Contradictions: The Emergence of the Literary Object in the Twelfth Century

- Part IV The Place of Thought: The Complexity of One in French Didactic Literature

- Part V Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry

- Part VI Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries

- Afterword

- General Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- Bibliography of Work by Sarah Kay

- Index

- Gallica

Summary

IT IS DIFFICULT to call to mind a vernacular French work more committed to concretising a didactic message through spatial allegory than Christine de Pizan's Livre de la Cité des Dames. Here, the author devotes her narrative to an involved metaphorical construction project, that of the eponymous City of Ladies. This space is envisioned by an intradiegetic Christine character and her divine guides, the personified forces of Reason, Rectitude, and Justice, as a physical stronghold in which virtuous women may take refuge from the calumny of men. The City of Ladies, however, is not nearly so materially territorialised as it may initially seem. The Christine character digs its foundations, for instance, using the ‘pioche de [s]on entendement’ (pickaxe of [her] intelligence). This non-pickaxe, which is not used for digging at all but, rather, for asking questions, produces a non-hole and, as the walls go up, the referent of the City metaphor becomes ever more obvious. The Christine character uses the ‘truelle de [s]a plume’ (trowel of her quill, 104) in order to build walls that are painfully difficult to imagine as stones joined together by mortar, but easy to identify as what they are: a series of literary exempla shaped in ink by a quill. The City of Ladies, in other words, is the Cité des Dames, an overlaying of text and space which the author is at pains not to conceal (Reisinger 2000: 629–31).

That the allegorical stronghold that is the City of Ladies should point so emphatically at its real-world referent of a literary text may seem at first glance to take a parodic stance with respect to the culture of didactic writing into which the Cité des Dames emerged. As Sarah Kay compellingly demonstrates, by the time the Cité des Dames was completed in 1405, spatial allegory had, for well over a century, figured the conceptual distance between physical bodies and their intellectual knowability by cultivating a kind of productive tension between territorially incarnate metaphor and the invisible work of thought.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Futures of Medieval FrenchEssays in Honour of Sarah Kay, pp. 200 - 212Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021