Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

7 - Masks and Politics

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

Summary

‘In the forest, when the branches quarrel, the roots embrace.’

(West African proverb: Fölmi 2015: 228)Masks for father

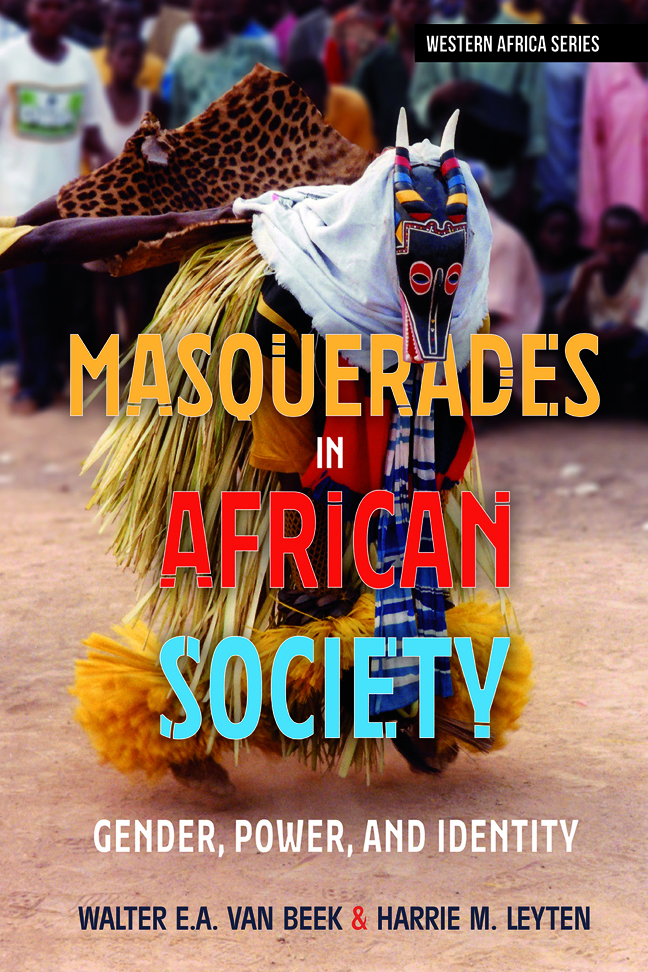

In a suburb of Abeokuta, in Yorubaland, the sound of drums heralds the approach of a masquerade. From all houses people emerge to see the parade, and children start dancing in anticipation of the spectacle. When the procession turns the corner, the mask comes into full view, surrounded by a host of excited people. Jumping to the rhythm of the drums, the mask with its finely carved wooden headpiece swings its long robes so that the layers of cloth become visible, layer upon layer. During the procession the mask is in the thick of things, surrounded by people and with drummers following it closely, and among the many attendants one elderly man is dressed in his finest gown. He is Ade, the pater familias of the Akinyode family, and clearly in charge of the whole feast. Women from his household sing in praise of the egungun, thus honouring also Ade Akinyode's late father, in whose remembrance the masquerade is being organised. They halt at the house of Chief Biobaku, where special songs are intoned to honour Akinyode's daughter, who is married to the chief. But it is Ade Akinyode himself who is central, for all people relate to him: the divining priest, the carver and the tailors, the herbalist, and finally the leader of the egungun cult. As a successful businessman in town and a prominent member of the egungun association, Ade is grateful to his late father for assisting him in setting up shop, and thus he has every reason to organise this masquerade.

Masks and the history of the patriline

The masking model that we have adopted implies that mask rituals find a favourite niche in societies where the power balances between men are under periodic redefinition and rely upon competing power bases. In such an open arena mask, rituals constitute a power source on their own that in principle is accessible to all males, so the core question is this: Who controls the masks and their rituals?

In this oro egungun performance of the Nigerian Yoruba, it is not the bush that enters the town; this full-cloth mask is quite urban, predominantly human, and points at relations between humans much more than it points at the wilderness.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Masquerades in African SocietyGender, Power and Identity, pp. 219 - 252Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023