Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Motherhood and Meaning in Medieval Sculpture

- 1 Motherhood as Transformation: From Annunciation to Visitation at Reims

- 2 Motherhood as Monstrosity: The Moissac Femme-aux-serpents and the Transi of Jeanne de Bourbon-Vendôme

- 3 Resurrecting Lazarus: The Eve from Saint-Lazare at Autun

- 4 Visualizing Parturition: Devotional Sculptures of the Virgin and Child

- Afterword: Motherhood and Meaning: Medieval Sculpture and Contemporary Art

- Bibliography

- Index

- Already Published

Introduction: Motherhood and Meaning in Medieval Sculpture

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Motherhood and Meaning in Medieval Sculpture

- 1 Motherhood as Transformation: From Annunciation to Visitation at Reims

- 2 Motherhood as Monstrosity: The Moissac Femme-aux-serpents and the Transi of Jeanne de Bourbon-Vendôme

- 3 Resurrecting Lazarus: The Eve from Saint-Lazare at Autun

- 4 Visualizing Parturition: Devotional Sculptures of the Virgin and Child

- Afterword: Motherhood and Meaning: Medieval Sculpture and Contemporary Art

- Bibliography

- Index

- Already Published

Summary

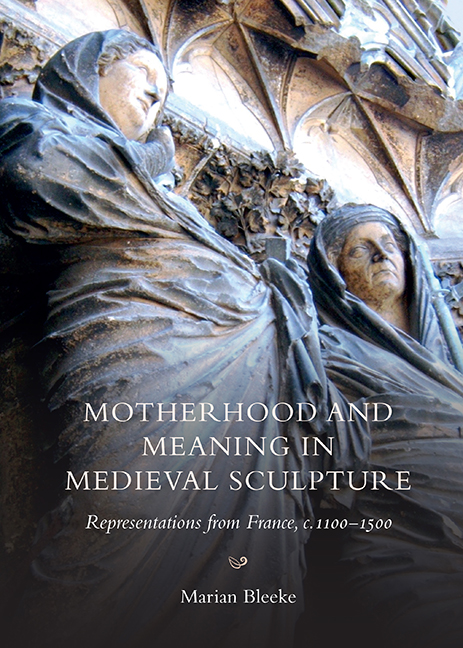

She stands with her weight shifted slightly to her left and with that hip pressed outward and upward, in a version of the classical contrapossto pose (Fig. 1 and Plate I). She puts that pose to a different end, however, propping an infant up on her hip and securing him against her body with a strong grasping hand. The child reaches out with one hand to grasp her veil and pull it over her chest – and with that gesture he calls attention to the play of fabric folds that the contrapossto pose creates on her lower body. On her right, a series of curves at varying depths cross over her body from her extended hand to where the child's body presses against hers. The topmost of these folds flips the garment inside out, revealing its white inner surface so that it rhymes visually with her white veil above. On her left, by contrast, the fabric gathers into tight folds along vertical lines that extend down from the pleats in the lower portion of the child's garment. And the end of her veil gathers into similarly tight folds as it dangles from his hand. The placement of this flare of folds against her chest calls attention to her breasts, which are further emphasized by curving lines that extend upwards to them as drapery folds created by the tight cinch of her belt below.

This book asks what this sculpture – an early fourteenth-century French Virgin and Child – along with a number of other medieval sculptural representations of women – including the Annunciation and Visitation pairs from Reims cathedral (Figs. 2–3), the femme aux serpents from the church of Saint-Pierre at Moissac (Fig. 8), the transi of Jeanne de Bourbon-Vendome (Fig. 13), the Eve from the church of Saint-Lazare at Autun (Fig. 16), and multiple other Virgin and Childs (Figs. 26–37, Plates I–IV) – have to say about medieval women's experiences of motherhood. The most obvious answer to that question is little to nothing: the work of anonymous but presumably male sculptors, often working for clerical and so (ideally) celibate male patrons, there is little to no chance that these artworks speak of motherhood on the level of their makers’ self-expressions.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Motherhood and Meaning in Medieval SculptureRepresentations from France, c.1100-1500, pp. 1 - 14Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017