Summary

What we call a mountain is … a collaboration of the physical forms of the world with the imagination of humans—a mountain of the mind.

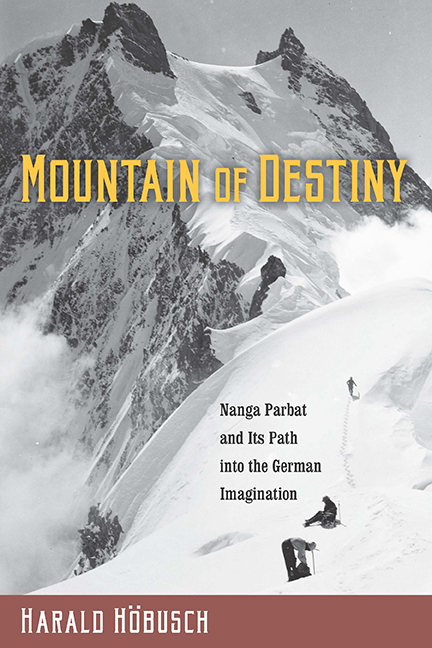

—Robert Macfarlane, Mountains of the MindIN 1924, IN HIS FIRST “TRUE” BERGFILM (mountain film), German director Dr. Arnold Fanck told the story of a fictional local climber (“The Mountaineer”) whose imagination was seized by the idea of scaling the Guglia del Diavolo, supposedly a forbidding rock tower in the Italian Dolomites. Again and again he attempts the perilous ascent, only to eventually fall to his death. His unfulfilled dream is finally realized by “His Son,” who, in the effort of saving his friend Hella during her own illfated attempt on the Guglia, reaches the summit. The title of Fanck's immensely popular mountain drama—a film that for seventy-two days in a row played to sold-out audiences in Berlin—was “Mountain of Destiny” (Der Berg des Schicksals).

Less than ten years later, as if following an unintended script, the fictional drama of Fanck's film—with its themes of mountaineering obsession, generational legacy, and ultimate triumph—would begin to play itself out for real, the fictional Guglia del Diavolo replaced by an actual, even more forbidding mountain, and the audiences’ fascination with the struggle of man against mountain rising to yet unseen heights. Never before or after, in fact, would a mountain capture the German imagination longer and more thoroughly than Nanga Parbat (from Sanskrit: Nanga Parvata, the “Naked Mountain”), located in the extreme western part of the Himalaya chain in present-day Pakistan, and at 8,125 meters the world's ninth-highest peak. Repeatedly referred to by 1930s mountaineers as the German “mountain of destiny,” Nanga Parbat—over a period of roughly two decades between 1932 and 1953—became not only the destination of six German mountaineering expeditions but also the quintessential German “mountain of the mind” onto whose slopes German mountaineers, mountaineering officials, politicians, writers, and filmmakers would project some of the most pressing social, political, and cultural concerns of their time.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Mountain of DestinyNanga Parbat and Its Path into the German Imagination, pp. 1 - 14Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2016