Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Terms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The Filed Story of Niederungen

- 2 Contact Stories: The Author and the Officer

- 3 Conspiratorial Stories: The Securitate Sources MAYER, SORIN, and EVA

- 4 Captured Stories: Remote Audio Surveillance

- 5 Migrating Stories

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Appendix I Müller’s Surveillance Timeline (1974–93)

- Appendix II Author’s Accreditation by CNSAS

- Index

4 - Captured Stories: Remote Audio Surveillance

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Terms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The Filed Story of Niederungen

- 2 Contact Stories: The Author and the Officer

- 3 Conspiratorial Stories: The Securitate Sources MAYER, SORIN, and EVA

- 4 Captured Stories: Remote Audio Surveillance

- 5 Migrating Stories

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Appendix I Müller’s Surveillance Timeline (1974–93)

- Appendix II Author’s Accreditation by CNSAS

- Index

Summary

We once entered the apartment of a family who had a cat. The feline ran out. You should have seen two or three Securitate colonels running after the cat.

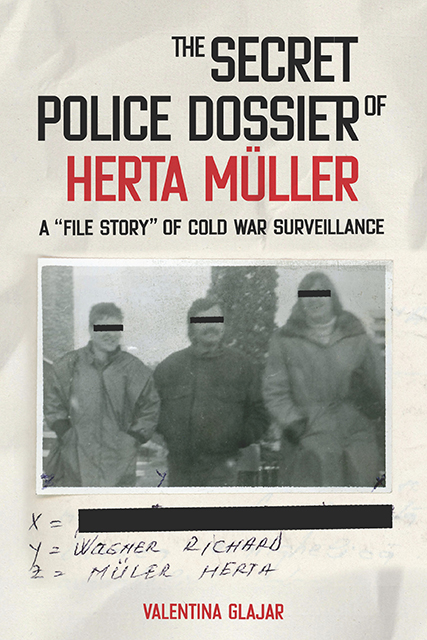

By the 1970s the Romanian Securitate had gained technology that allowed them to implement a more sophisticated layer of remote surveillance that was intrusive and unforgiving, exposing its targets’ intentions and activity at a heightened level of transparency. Not biased or subjective, the listening devices, when working properly, provided unfiltered access to the targets’ innermost privacy (fig. 4.1). While informers’ reports rendered events through their own perspective informed by habitus, expectations, and attitude toward their targets, T.O. was designed to erase the personal inaccuracies and imprecisions found in those reports.

In a 1971 issue of Securitatea, a top-secret publication dedicated to the work of the agency, various officers answered questions about a range of topics related to their activity and based on their experiences. One question referred to the most efficient means of surveilling and verifying informers, and their opinions were divided, with a majority of the officers siding with “special means”— bugging or wiretapping. In the experience of Lt.-Col. Constantin Ionescu, for example, technical sources were helpful if only they could be more easily installed and exploited—an issue no longer topical in today's digital surveillance era. Informers, on the other hand, memorized and related different aspects of a certain objective, and in the end, if they were sincere, the information they provided would come together. Major Constantin Jipa appreciated the possibilities of remote surveillance but also highlighted its limitations. He favored good informers over any technical devices, because they were active, could engage their targets in conversation, and could ask the appropriate questions at the right time. Major Vasile Stan disagreed since, in his opinion, informers could not memorize everything, did not report certain aspects, or ignored others that would otherwise be noteworthy to the Securitate officers. Technical devices, on the other hand, were perfectly objective. Captain Tudor Savu had the last word, and his choice was technical sources, but in combination with direct human intelligence. Remote surveillance, with all its advantages and limitations, was a priority for the Securitate, which was eager to gain access to its targets’ conversations taking place in the privacy of their homes.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Secret Police Dossier of Herta MüllerA 'File Story' of Cold War Surveillance, pp. 190 - 227Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023