Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Piercing the Skin of the Present

- Part I

- Part II

- 5 Show Them What Cleaning Is: This Time It's for Mama

- 6 Who Can See this Bleeding? Women's Blood and Men's Blood in these #Fallist Times

- 7 The Bloody Fingerprint: We Must Document

- Bibliography

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

7 - The Bloody Fingerprint: We Must Document

from Part II

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 March 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Piercing the Skin of the Present

- Part I

- Part II

- 5 Show Them What Cleaning Is: This Time It's for Mama

- 6 Who Can See this Bleeding? Women's Blood and Men's Blood in these #Fallist Times

- 7 The Bloody Fingerprint: We Must Document

- Bibliography

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Summary

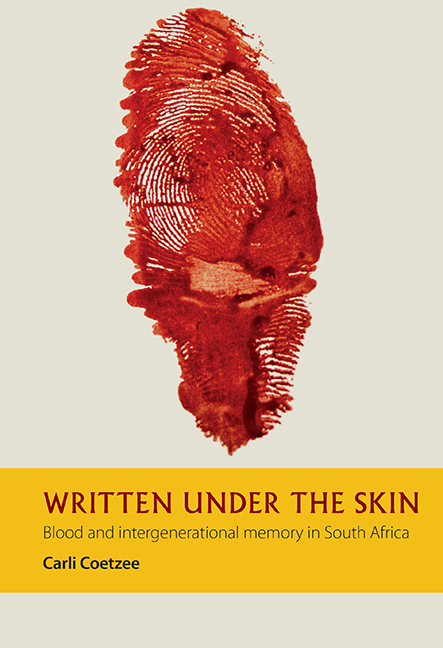

The South African visual artist Zanele Muholi mobilises the complex meanings of a bloody fingerprint in her series of artworks called Isilumo Siyaluma (period pain, or the pains associated with periods), the prototype of which provides the cover for this book. Muholi's menstrual artworks are made with a particular kind of blood, blood that in some languages is named differently so as to distinguish it from other bloods. Menstrual blood is differently valued symbolically, and its relation to the skin or surface of the body is distinct. The bleeding of menstruation is the result of the body naturally shedding the thickened (invisible and internal) womb lining, which replenishes itself after being shed, then grows and is shed again cyclically (periodically, as the name indicates). Menstrual blood is the body's mode of self-regulation, but it also structures and punctuates time. It is different from the other bloods that flow in a closed circulatory system through our bodies and which are brought to the surface in a blood test.

The menstrual cycle has an invisible phase (unremarkable, and unremarked upon), followed by the hyper-visible phase when bleeding occurs. This bleeding has, at various times and in various contexts, required menstruating women to be separated or to bring ourselves and our blood into invisibility. A vast scholarly and activist literature has reflected on and analysed these prohibitions, and the shame and embarrassment associated with visible menstrual blood. When menstrual blood rises to the surface (on clothing or on furniture) it has extraordinary power to unsettle and cause discomfort. It is these meanings of blood that are brought to the surface of the canvas in Muholi's work.

To make the Isilumo Siyaluma series, Muholi collected her own menstrual blood, pressed her finger into the fluid and then made prints, using her finger dipped in the blood as paint. The viscosity of menstrual blood makes it different from other human bloods as a painterly medium, and most women are used to touching this blood (at least from our own bodies). There is a welldocumented tradition of menstrual art by women artists, and Muholi's work is informed by this tradition but with activist agendas shaped and inflected by her own location. In discussions by Pumla Dineo Gqola (2006) and Nomusa Makhubu (2012) these situated agendas are shown to be central to Muholi's activist project.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Written under the SkinBlood and Intergenerational Memory in South Africa, pp. 147 - 154Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019