Introduction

This Element introduces the life and teachings of philosopher and teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), a South Asian from India who offered a unique perspective on expansion of human consciousness. His message centers on individual self-inquiry as the only practice useful for discovering freedom from the conditioning of society and for ultimate self-realization.

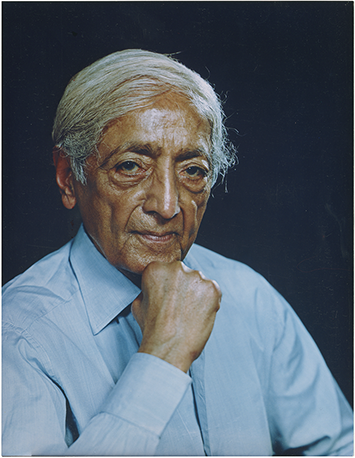

Described as “the quintessential iconoclast of the twentieth century” (Sanat Reference Sanat1999: xi) and “the eminent thinker of our age” (Mehta Reference Mehta1987: 54), Krishnamurti, by any measure, led an extraordinary life. After a somewhat obscure childhood in south India, he attained international notoriety at age fourteen when he was identified by the Theosophical Society as the vehicle for the prophesied World Teacher of this cosmic age. Before reaching adulthood, he was venerated and served as head of a worldwide order established in his name. After twenty years Krishnamurti disbanded the order and became a teacher in his own right, without benefit of any organization. For more than sixty years on a public circuit, he addressed thousands of audiences, primarily in India, England, the United States, and Europe, and met with scholars and practitioners in several fields for dialogues, aimed at observing consciousness in the moment through collaborative inquiry. His teaching and his personality influenced world leaders in politics, science, religion, and philosophy, and his writings continue to be cited for their insights into the human condition (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 J. Krishnamurti, 1982.

Section 1 traces Krishnamurti’s childhood, his appointment by the Theosophical Society as the vehicle for the prophesied World Teacher, and the onset in 1922 of the transformative Process that affected his entire being. Section 2 explains his life as a teacher after 1929 when he disbanded the order instituted in his name and became an independent teacher. Section 3 contextualizes his teaching within his life, aligning elements of his message with his personal experience. Section 4 explores Krishnamurti’s definition of the religious life as a principle of unification that transforms the habitual fragmentation of the psyche into a mind characterized by wholeness and order. Section 5 describes Krishnamurti’s commitment to the possibility of an unconditioned mind, a state of persistent meditation in everyday life, that can open all individuals to the search for truth through engagement with the unknown. Section 6 explores his teaching about human possibilities of transformation, which include the identification of each person with the whole, summarized by his phrase “you are the world.” Section 7 examines Krishnamurti’s engagement with scientists and philosophers, particularly highlighting his dialogues with theoretical physicist David Bohm. Section 8 analyzes his educational philosophy and looks at the ways in which education can lead to personal liberation and transformation. Section 9 summarizes the legacy of Krishnamurti’s teachings.

This Element argues that the life and teachings of Krishnamurti are so intertwined, that he does not represent any tradition of self-realization or identifiable cosmology, but rather teaches directly out of his own insights. What he discovered himself aligns clearly with nondual philosophies of enlightenment that call upon each individual to search for truth and be responsible for their own trajectory through life. Because he did not establish a formal organization or proselytize for a defined membership, however, the scope of his influence is not easily delineated, lying primarily within informal exposure to his message. Research into his life reveals controversies, described herein, which pertain to the details of his personal experiences, the content of his teaching, his unique presentation, and his prescribed methods. These controversies are presented without providing a final determination.

Sources

This Element relies on several types of resources for its content – biographies, Krishnamurti’s personal journals, reminiscences by associates, audio and video tapes of addresses and dialogues, and commentaries on the teaching. Reports of his life draw primarily from two sources. First, the comprehensive biographies by Mary Lutyens (1908–1999) (Reference Lutyens1975, Reference Lutyens1983, Reference Lutyens1988, Reference Lutyens1990, Reference Lutyens1996), daughter of Lady Emily Lutyens (1874–1964), one of Krishnamurti’s closest friends, and Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944), architect and designer of New Delhi, the capital of independent India. Mary Lutyens grew up alongside Krishnamurti from 1911 when she was three years old (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: ix). Second, the biography and dialogues reported by Pupul Jayakar (1915–1997) (Reference Jayakar1986, Reference Jayakar1995), who met Krishnamurti in India in the 1940s and served as his intellectual amanuensis, watching over him through a recurrence of the mysterious “Process” in 1948 (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986, Reference Jayakar1995). Both Lutyens and Jayakar note the development of Krishnamurti’s teaching as largely a function of the challenges and lessons met in his own life’s trajectory. Other less comprehensive biographies and reminiscences by associates also contribute to the depiction of Krishnamurti’s life.

Accounts of the teaching itself draw from a variety of sources: Krishnamurti’s own writings and personal journals; recordings and transcriptions of his talks and dialogues; scholarly analyses (both appreciative and critical) by academics, scientists, and educators; descriptions of the schools and foundations organized in his name; and reflections by those who have observed his teaching in their lives. Primary and secondary literature concerning his influence on the study of consciousness and transformation, his demonstration of dialogical exchange in his teaching, and the dialogical process developed with David Bohm are also utilized.

The published corpus is vast, including 107 books currently in print (some of which are translated into 31 languages), 600 videos, and 2,500 audio recordings, mainly derived from lectures Krishnamurti gave over his lengthy career (Lee Reference Lee2024). The talks, all delivered in English, invariably cover wide-ranging topics so that any single talk might span the breadth of his teaching – from the function of thought to an analysis of global disharmony (Van der Struijf & Van der Struijf Reference Van der Struijf and Van der Struijf2000). Almost all public addresses given by Krishnamurti in his later life are available in audio and video formats. Additionally, two full-length films review his life and teaching (Mendizza Reference Mendizza1985, Reference Mendizza and director1990).

Along with other foundations relating to Krishnamurti and his teachings that exist around the world, the Krishnamurti Foundation of America (KFA, www.kfa.org) maintains a library, bookstore, archive, and web presence. The KFA’s presence on the internet includes current usage of Facebook (300 K followers), Instagram (206 K followers), TikTok (48.9 K followers), YouTube (1.5 M views), the KFA Newsletter (66.5 K subscribers), and “The Immeasurable” (7.9 K users) (Lee Reference Lee2024).

1 Boyhood and Early Life with the Theosophical Society

Jiddu Krishnamurti was born in 1895 in Madanapalle, Madras Presidency (now Andhra Pradesh), into a Telugu-speaking Brahmin family steeped in the traditions of Hinduism and a sacred view of the world. His great-grandfather had been an eminent Sanskrit scholar and his grandfather also a learned man and civil servant in colonial India. His father, Jiddu Narianiah (d. 1924), a graduate of Madras University, served in the Indian Civil Service as an official in the Revenue Department and later as District Magistrate (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 1). Krishnamurti’s mother, Sanjeevamma (d. 1905), was a pious and charitable woman known for her devout nature, psychic gifts, and paranormal visions. She had a premonition that her eighth child would be in some way remarkable and insisted that the baby be born in the puja room, a special room set aside in orthodox Hindu households for prayers, usually proscribed for any polluting activity such as childbirth (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 15–16). Consistent with orthodox Hindu tradition, immediately after birth, Krishnamurti’s horoscope was cast by an astrologer, who predicted that the child would become a great teacher, but only after encountering significant obstacles (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 16). According to Hindu observance, six days after the birth of a child, the important name-giving ceremony is held. Jiddu Narianiah and Sanjeevamma, following tradition, named their eighth child “Krishnamurti” (literally “the image of Krishna”) after the Lord Krishna, himself an eighth child (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 17).

At the age of six, Krishnamurti went through the sacred thread ceremony, upanayana – initiation into the first of four stages of life of a twice-born male or brahmacharya, specified in ancient custom for all Brahmin boys at the beginning of their life of study and discipline (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 17). As part of the initiation ceremony, the Hindu priest placed the sacred thread over Krishnamurti’s right shoulder and his father whispered the sacred Gayatri Mantra – invocation to the sun – into his ear. According to Narianiah, “It is a ceremony which Brahmin boys go through when it is time to launch them out into the world of education” (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 17). After the initiation ceremony, the young boy was taken to a Hindu temple for prayers and then on to the nearest school and “handed over to the teacher” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 3) to begin his education. All these rituals are integral to the orthodox Brahmin tradition of Hinduism and Krishnamurti’s family strictly observed each rite.

As Brahmins, the Jiddu family belonged to a high caste, the significance of which cannot be overstated. Brahmins represent a spiritual rather than an economic elite and constitute, according to Hindu tradition, the hereditary group that has arrived, through karma and reincarnation, at the last and highest stratum of spiritual evolution. Traditionally, they are considered purer in mind and body than the lower castes and thus constitute the caste from which temple priests and religious scholars derive (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 2). Throughout his childhood, Krishnamurti’s life was circumscribed by the conventions of caste and “the rituals, theology, and ethics of Hinduism would have been second nature to him, a matter of domestic routine” (Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 27–8).

The young Krishnamurti was physically delicate and suffered several recurring illnesses, including malaria. Repetitive bouts of fever combined with Narianiah’s frequent transfers of residence interrupted the boy’s schooling so that “in lessons he fell far behind other boys his age” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 4). A quiet and contemplative child, often lost in dreamy imaginings, he drew negative judgments, including inferior mental functioning, from his teachers and peers. His mother seems to be the one person who appreciated his unusual behavior and saw his dreaminess as a type of gift, rather than stubbornness or lack of intelligence (Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 28). Krishnamurti relates that his happiest memories of childhood center around the time spent with his mother, who would conduct Hindu worship, puja, in the family shrine, send him out to distribute rice to beggars, and teach him about karma and reincarnation. After his mother’s death, he saw his mother’s image in visions, a fact confirmed by his father Narianiah (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 4–6).

Up to the age of ten, when Krishnamurti’s mother died, the family was intact. Throughout his first ten years, both his father and mother taught him at home, adhered to Brahminical practices, and introduced him to the teaching of the Theosophical Society. His father attended conventions of the Society in Madras and held meetings at the family home for the study of Theosophical ideas (Krishnamurti in Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 19).

Both parents respected Annie Besant (1847–1933), who became president of the Theosophical Society in 1907 and, as described later, was to become the adoptive mother for Krishnamurti and his brother Nityananda, and a central figure in Krishnamurti’s life until her death in 1933. In 1907 after the death of his wife, Narianiah wrote to Besant “to offer his ‘whole-hearted and full time service’ in any capacity in exchange for free accommodation for himself and his sons in the Compound of the international Headquarters of the Society at Adyar near Madras” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 7). After an initial rejection of this request, Besant agreed to accept his services and in January, 1909, Narianiah took a position as assistant secretary in the Theosophical Society and moved with his four sons to the international headquarters of the Theosophical Society at Adyar, outside Madras (now Chennai), India (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 7).

The Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 in New York City by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–1891), Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), and William Q. Judge (1851–1896), began as an organization dedicated to a synthesis of science, religion, and philosophy with the credo, “There is no religion higher than truth.” The founders sought to promote the study of insights from various world religions, investigate occult phenomena, and foster the brotherhood of all humankind.

The Theosophical Society with international headquarters at Adyar, in Tamil Nadu state, defines its teaching not as a religion per se, but rather as a restatement of the essence of religion itself by affirming three objectives:

1. to form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of Humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or color;

2. to encourage the study of Comparative Religion, Philosophy, and Science; and

3. to investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humans. (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 10)

The Preamble to the bylaws refers to the hope of penetrating further than science into “the esoteric philosophies of ancient times” (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 28).

Although Olcott became the first president (1875–1907), the writings and teachings of Blavatsky became synonymous with the tenets of the Society. The Society accepted Blavatsky’s self-description as a disciple of highly evolved beings, mahatmas or Masters of Wisdom, who had instructed her in esoteric truths that she referred to as the ancient wisdom, the secret doctrine, or Theosophy (meaning divine wisdom). Her reports include personal contacts with an occult brotherhood of these Masters made during her travels in the Far East, particularly in the Himalayas (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 54–61). Their teachings, Blavatsky states, deemed to be perennial truths and the universal basis of all valid religions, were transmitted directly to her and became the basis of her writings (Murphet Reference Murphet1975; Campbell Reference Campbell1980), most notably Isis Unveiled (Blavatsky Reference Blavatsky1877) and The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy (Blavatsky Reference Blavatsky1888), which remain foundational to the Society’s ontology and cosmology.

Even within Theosophical circles, Blavatsky’s narratives of her travel to the Himalayas and her direct tutelage by the Masters there have been surrounded by doubt and controversy, based primarily on independent scholarly investigation of the content of the writings themselves as well as lack of any independent sources to validate her claims (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 56–61). Challenges to her personal narrative as well as the content of the teaching include charges of plagiarism, unacknowledged Western esoteric roots – particularly Masonry and Rosicrucianism – and inconsistencies in the universal wisdom proffered by the Masters, alleged to be omniscient (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 56–61; Godwin Reference Godwin1994: 326–8; Washington Reference Washington1995: 26–46). Even though questions persist concerning Blavatsky’s biographical narrative, the provenance of received truths, and her idiosyncratic approach to occult communication, the existence of the Masters and continuing communication from them remain central to the perspectives of most Theosophists (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 60–1, 178–87). From the earliest days of Blavatsky’s personal narrative, two Masters figure prominently in Theosophical thought – Kuthumi (Koot Hoomi) and Morya – both of whom also appear in the life of the young Krishnamurti as he was schooled at Adyar (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 10–11; Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 81).

After 1879 when Blavatsky and Olcott traveled together to India and began to champion Indian aspirations for political unification and a revival of the Indian people’s pride in the history, religion, and culture of their country, the Society attracted educated and influential British colonialists as well as Indians as members (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 78–83). Further, in 1880, they were welcomed in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) as Western champions of Buddhism as they worked with Sinhalese Buddhists in efforts to limit the influence of Christian evangelism, considered prejudicial and vituperative (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 83–7). As Olcott stated, the Society in its commitment to no particular religion was “as loyally working with Indians to promote Hinduism as it had been with the Sinhalese Buddhists to revive Buddhism” (Olcott cited in Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 86).

Interest in Theosophical principles grew in America, Europe, and India. In large part, Theosophical ideas are consistent with the cosmological and psychological teachings of Hinduism and Buddhism – with explorations into esoteric Christianity – and are portrayed in an amalgam of Hindu and Buddhist terminology, particularly using the concepts of evolution, karma, and reincarnation (Hanegraaff Reference Hanegraaff2006: 1114–21; Jones & Ryan Reference Jones and Ryan2007: 444–5). The synthesis of East and West, religion and science, as well as spiritual and educational understanding, made Theosophy attractive to cosmopolitan, liberal people of many nationalities who had been disappointed by the dogmatism of both religion and science. These progressives sought to unite the diverse peoples of the world in a peaceful brotherhood (Hanegraaff Reference Hanegraaff2006: 1114–16).

Part of Theosophical teaching, from the time of Blavatsky and creation of the Society’s Preamble, is the exploration of occult and clairvoyant powers for discovering the hidden mysteries of nature and the esoteric powers of humanity. Founding Theosophists used their understanding of esotericism to draw from a host of related movements that included the occult sciences of astrology, alchemy, ritual magic, divination, Spiritualism, and psychism as well as distinct movements such as Gnosticism, Pythagoreanism, Neo-Platonism, Hermeticism, Kabbalah, and Rosicrucianism (Godwin Reference Godwin1994: 277–362). Foundational to the diversity in these movements is the esoteric assertion that an individual can comprehend symbol, myth, and ultimate reality only through a personal struggle for progressive illumination on successive levels (Faivre and Needleman Reference Faivre and Needleman1995: xii). This personal struggle involves “functioning effectively in the external world and … submitting oneself to a more conscious and transcendent reality that is contacted within the self” (Faivre and Needleman Reference Faivre and Needleman1995: xxvi).

Theosophy combined these tenets of Western esotericism with Buddhist and Hindu ontologies to form a worldview that includes a complex cosmology, a metaphysical psychology, an esoteric physiology, and an evolutionary scheme that encompasses eons of cosmic and planetary changes. Esoteric tenets from the West meshed well with Theosophical understanding of Asian concepts of reincarnation, karma, and progression through spiritual evolution toward self-realization (de Purucker Reference De Purucker1979). For understanding and practice of the tenets of esotericism, Olcott in 1888 ordered formation of an Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society, which “legitimated Madame Blavatsky’s desire to pursue occult instruction with an elite group within the Society” (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 98). Blavatsky herself acted as leader, “known as the Outer Head – the Inner Heads being the Mahatmas (Masters) with whom she was supposed to have direct ties” (Hanegraaff Reference Hanegraaff2006: 1119). Although multiple divisions and dissensions have surrounded the operation of both the Esoteric Section and the Theosophical Society since their beginnings (Godwin Reference Godwin1994: 362; Hanegraaff Reference Hanegraaff2006: 1119), the section has endured until today, operating in secret with its own order of practices and rituals.

The combination of an esoteric worldview, belief in an occult hierarchy, and the Indian, European, and American community of seekers brought together in the Society constituted the milieu in which the young Krishnamurti was immersed in the next two decades of his life, from 1909 to 1929 (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975; Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 120–50; Jones Reference Jones, Melton and Bauman2010).

Discovery of the Vehicle for the World Teacher

In 1889, Annie Besant, a prominent figure in progressive movements in England, who would become central to the workings of the Society as a whole and Krishnamurti’s life in particular, read Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine, an act that would change her life in significant ways. Besant (née Wood) was born in 1847 in London, raised in the Church of England, married a minister in the church, and bore two children. With each passing year, her unhappiness in marriage, the severe illnesses of her children, her acute observations of the social inequities surrounding her, and her own diligent inquiries into theological questions prompted her to question the doctrines of the church on many grounds (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 41–64). She left her husband and became a “passionate crusader for freedom of thought, women’s rights, trade unionism, Fabian socialism, and birth control” (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 22). Self-identified as an atheist, she used her considerable gift as an orator to deliver public addresses on reform of many social ills. But, upon reading Blavatsky’s work, she “turned her enormous energies from materialism and atheism to the pursuit of the occult and sacred” (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 22). She soon joined the Theosophical Society, became the most favored protégé of Blavatsky, and joined the Inner Group of the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society, which functioned to maintain contact with the Masters (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 65–6).

Besant took up residence at the headquarters of the International Society at Adyar and became its president in 1907. She continued her work for social reform begun in the United Kingdom by working to improve social conditions in India, founding many schools, and leading in the movement for Indian Home Rule (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 2–3). Although not a supporter of Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagraha (nonviolent resistance) campaign, her participation in Indian politics as a moderate proponent of Home Rule led to her popularity, and she was elected the first woman president of the National Congress of 1918 (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 2–3).

Alongside these extraordinary achievements, Besant at the same time was convinced of India’s special role in spiritual evolution. She spoke of her conviction that India’s mission in the world is to share its genius for religious and spiritual knowledge (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 22–3).

If religion perish here, it will perish everywhere and in India’s hand is laid the sacred charge of keeping alight the torch of spirit amid the fogs and storms of increasing materialism. If that torch drops from her hands, its flame will be trampled out by the feet of hurrying multitudes, eager for worldly goods; and India, bereft of spirituality, will have no future, but will pass on into the darkness, as Greece and Rome have passed.

Underlying Besant’s fervor for India’s mission was another prediction for world change. Termed “progressive messianism” (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 27), Besant’s perspective entailed “a progressive and evolutionary view of history with the hope for a terrestrial salvation that will be accomplished imminently by a messiah who will enter the historical process to effect a radical but non-catastrophic change” (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 27).

Besant accepted Blavatsky’s complex evolutionary scheme involving sequential “Root Races” (or dispensations) of humanity with members of the Occult Hierarchy officiating to usher in each new dispensation. According to Besant, Blavatsky’s secret teachings, given only to her advanced students, specified that the “inner purpose of the Society was to prepare the world for the coming of a new Race” and identified Master Kuthumi and Master Morya as the two Teachers who would officiate at the coming of the new age (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 275–6).

But it was Besant who would use her own occult powers (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 279) and research skills to enhance Blavatsky’s description of the advent of a new civilization, by predicting the appearance of a World Teacher, or Bodhisattva, to usher in the new Root Race. According to Besant, a “World Teacher appeared on earth every time a sub-race was beginning” and, further, “all religions were delivered by a World Teacher” (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 270–5). Besant placed this emissary above the Masters in the Occult Hierarchy in a more distinctive rank – that of World Teacher or Lord Maitreya, the same consciousness that inhabited Lord Krishna in Hinduism and Jesus Christ in Christianity. This consciousness, she predicted, would soon incarnate into a contemporary person, who would serve as the “vehicle” of the World Teacher to bring a new teaching on a global scale (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 11). According to her insights, the World Teacher for the Sixth Root Race would be characterized by love and service, similar to the principle of a Bodhisattva, rather than the characterization of the Teacher of the previous Fifth Root Race, who was characterized by mind (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 270–7).

Besant saw her most important personal contribution to this messianic narrative to be preparation of the world for the appearance of the World Teacher (Wessinger, Reference Wessinger1988: 270–1). In l896, five years after Blavatsky’s death, Besant publicly affirmed this expectation of a World Teacher, who would arrive imminently (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 12–13).

Besant was soon joined in leading the Theosophical anticipation of welcoming the World Teacher by another British citizen, a former Anglican clergyman with reputed powers of clairvoyance, Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854–1934). Ordained to the priesthood of the Church of England in 1879, Leadbeater drew upon his already avid interest in the supernatural and Spiritualism when he read the stories of Blavatsky’s contact with the Masters (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 26) and made her acquaintance in 1884 in London. The very next year in Blavatsky’s presence, Leadbeater experienced his first meeting with a Master named Dwal Khul, which began a communication with other Masters that was to continue until his death (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 39). According to Leadbeater’s primary biographer, Blavatsky “totally transformed and remade his personality, changing him from an ordinary curate … into a pupil of the Masters” (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 40).

Although Besant and Leadbeater had met in 1894 in England, it was in 1909 that Leadbeater settled into the routine of Theosophical life at Adyar when he took charge of The Theosophist, a journal published by the Society, and began to document his occult investigations (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 102). In regular talks and writings, he came increasingly to identify himself as an occultist who claimed “regular communication [through clairvoyance] with the Powers that govern the earth from the Inner Planes, the Masters or Mahatmas, the Supermen who constitute the Occult Hierarchy of the planet” (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 1) – the same mahatmas who Blavatsky reports taught her the mysteries of the universe (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 53–6).

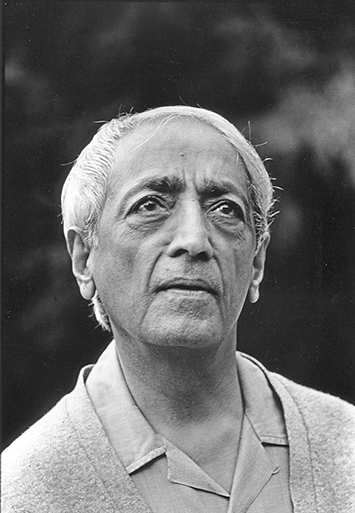

In April 1909 during a swim with his young assistants at the Theosophical estate at Adyar, Leadbeater had a chance encounter with Krishnamurti and his younger brother Nityananda (1898–1925). While Leadbeater’s companions were drawn to the outgoing Nityananda, Leadbeater focused on the more withdrawn older brother (see Figure 2) and reported that the boy “had the most wonderful aura he had ever seen, without a particle of selfishness in it … and that one day the boy would become a spiritual teacher and great orator” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 21). Leadbeater’s fascination could not have been based on Krishnamurti’s outward appearance, as he was “under-nourished, scrawny and dirty” and his “vacant expression gave him an almost moronic look” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 21). Yet, Leadbeater soon declared “that the boy was to be the vehicle for the Lord Maitreya ‘unless something went wrong’ and that he, Leadbeater, had been directed to help train him for that purpose” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 21).

Figure 2 J. Krishnamurti, c. 1924.

Besant was informed of and accepted Leadbeater’s “discovery” of Krishnamurti as indeed the vehicle of the awaited World Teacher, which, in effect, ousted Hubert van Hook, previously selected by Besant as the possible vehicle (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1983: 24–5). Krishnamurti and Nityananda were then removed from their school, given residence at the Theosophical headquarters in Adyar, and instructed personally by Leadbeater. According to Leadbeater, he would take the boy Krishnamurti every night in his astral body during sleep to learn from Master Kuthumi. Each subsequent morning, Krishnamurti would write notes about the meeting with Master Kuthumi, but because the boy’s English was not excellent, Leadbeater edited the notes to make sure that no mistakes were included. Leadbeater then typed the notes himself and finally took the manuscript clairvoyantly to Master Kuthumi and even to the Lord Maitreya himself for validation (Leadbeater in Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 135–9). Concerning his tutelage, Krishnamurti later related that he “began to see the Master K. H. [Kuthumi] in the form put before me. Later on, as I grew, I began to see the Lord Maitreya … (and later) the Buddha” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1983: 13).

Beginning in the 1890s, Leadbeater had conducted research into the past lives of Society members – a project that became his preoccupation once Krishnamurti was identified as the vehicle. Using clairvoyance, Leadbeater identified the particulars of thirty lives of Alcyone (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 108), the name given to Krishnamurti throughout his successive lives – enough to fill two large volumes (Besant and Leadbeater Reference Besant and Leadbeater1924). The method by which Leadbeater received these details was observed as identical to any author dictating his creative works to a secretary, that is, completely unverified by any other observer (Nethercot Reference Nethercot1963: 141). For this reason, the transmissions received by Leadbeater as well as his regular communications with the Masters were held in suspicion by many in the Society and prompted charges of deliberate fakery (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 114–15). Others, including Besant, defended Leadbeater’s integrity and the extent of his clairvoyance.

In 1910, the first book attributed to Krishnamurti, At the Feet of the Master (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1974), was published under curious circumstances. The book’s author was specified as Alcyone, the name attributed to the soul of Krishnamurti and its many incarnations. Leadbeater became fascinated with tracing the lives of Alcyone, which he reported spanned a period “from 22662 B.C. to A.D. 624” (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 114). The book, a first-person account of the lessons derived by Krishnamurti/Alcyone from study with Master Kuthumi on the higher planes, remains in print as a “guide for the pupil seeking spiritual and occult development” (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 137). Authorship of the book became a matter of dispute, however. Because Leadbeater directed the nightly sessions between Krishnamurti and Master Kuthumi and edited all of Krishnamurti’s notes – which are no longer extant – “there was no way of measuring to what extent Leadbeater had revised or altered [Krishnamurti’s] words” (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 137). The dispute over authorship of the book, whether Krishnamurti or Leadbeater, persists, with evidence that Krishamurti himself denied authorship in a clear statement to his father (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 138–9).

Around the turn of the twentieth century the Theosophical movement had begun to decline, but under the formidable leadership of Annie Besant, many lodges in Europe, America, and India revived (see Figure 3). As president of the Society, Besant, with the aim of drawing together those who believed in the coming of the World Teacher and were willing to contribute to his mission, initiated several groups within the Society, culminating in 1911 with the creation of the Order of the Star in the East (OSE) and an accompanying journal The Herald of the Star, with Krishnamurti as nominal editor.

Figure 3 J. Krishnamurti and Annie Besant, c. 1924.

Following the creation of the OSE, dissension arose among Society members who held that Besant had imposed an occult adventist agenda and messianic opinions about Krishnamurti on members of the Society who were clearly not amenable, as these impositions extended far beyond the three original objectives of the Society (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 46). Among some Theosophists, Besant’s “proclamation of the World-Teacher [sic] and the progressive messianic movement as embodied in the Order of the Star in the East” was a “departure from Theosophy as taught by Madame Blavatsky” and was termed “Neo-Theosophy” (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 275–7). Because of these differences between the original aims of the Theosophical Society and those of “Neo-Theosophy,” Besant created and maintained an organizational distinction between the Theosophical Society and the OSE. Apart from these disagreements, however, the Society and the OSE were hardly distinguishable, as the same people attended meetings and held high office in both organizations. As a result, “some members, and indeed whole sections of the Society, disagreed, and departed” (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 138–9). The OSE claimed 43,000 members in its annual report of 1926, two-thirds of whom were also members of the Theosophical Society (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1990: 62). In 1927, the OSE was reorganized to reflect the fact that the awaited coming of the World Teacher had changed to reflect, in Besant’s words, that “The World Teacher is here” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1990: 67) and was renamed The Order of the Star.

Beginning in 1911 and continuing over the next decade, under the guardianship of Besant and the continued instruction by Leadbeater and several tutors, Krishnamurti studied English, history, mathematics, and sports. Leadbeater personally oversaw Krishnamurti’s maturation in his understanding of the Society and its occult teachings (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 45–6). As an adept at occult matters, Leadbeater claimed that he was present clairvoyantly during sleep at the initiations of various Theosophical Society members into higher and higher planes of existence, which he reported to each member after waking the next morning. Krishnamurti’s progressive initiations on the astral plane were reported in this fashion (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 129–34). Specifically, Leadbeater reported, Krishnamurti was accepted as a student of Master Kuthumi who vouched for his worthiness and entrusted Leadbeater and Besant to help him on his upward way in the outer world (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 131). In this way, Krishnamurti’s life was planned and directed through instructions from Master Kuthumi, transmitted through Leadbeater.

While Narianiah was living outside the Adyar compound, Krishnamurti and his brother were living inside, near Besant and Leadbeater, and took their meals there. In 1910, Narianiah transferred guardianship of his sons to Besant. In 1911 and extending for several years, a scandal ensued surrounding Leadbeater’s impropriety regarding sexual conduct with boys in his charge, including Krishnamurti and Nitya. In 1912, Narianiah complained to the District Judge of Chingleput that his sons were being corrupted through unnatural acts by Leadbeater and sought to annul any grant of guardianship to Besant, who did not keep the boys separate from Leadbeater. Narianiah alleged that he witnessed improper and unnatural acts between Leadbeater and Krishnamurti. Besant fought to retain guardianship. Several court cases ensued, ending with an appeal to the Privy Council in England, which decided in Besant’s favor, so that Krishnamurti and Nitya were under the guardianship of Besant until they reached the age of eighteen (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 54–84; Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 140–57). Although the facts surrounding Leadbeater’s improprieties concerning young boys remain controversial, it appears evident that Leadbeater “had no sexual relationship with Krishnamurti or Nityananda” even though “there were ‘irregularities’ in Leadbeater’s relationships with his closest pupils on other occasions, and Mrs. Besant was aware of this fact, but unwilling, or unable, to take any action” (Tillett Reference Tillett1982: 155).

At the Theosophical Convention at Benares in December 1911, Krishnamurti was to demonstrate the first manifestation of the Lord Maitreya, which Leadbeater felt as a “tremendous power flowing through him [Krishnamurti],” and prompted others in attendance to fall at his feet and weep (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1990: 16). The next day, Besant informed the Esoteric Section that “after what they had seen and felt, it was no longer possible to make even a pretence of concealing the fact that Krishna’s body had been chosen by the Bodhisattva and was even now being attuned to him” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1990: 16). Following this pivotal event and the conflict over custody of Krishnamurti and his brother, Krishnamurti began to exert some personal independence, but remained largely under the guidance of Besant and the instruction of Society members at Adyar. His independence would grow exponentially with his experiences in the 1920s.

The Process

In 1922 Krishnamurti, now in his twenties, and Nityananda traveled to Sydney, Australia, to attend a Theosophical convention. After deciding to visit the United States on their return to Europe, they were invited to spend time in Ojai, California, near Santa Barbara. The remote valley afforded a location for the brothers to be alone together, and its dry climate was particularly helpful for Nitya’s tuberculosis, a growing concern. Krishnamurti was “enchanted with the beauty of the countryside,” and Besant later bought the property for the brothers (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 46–7). Named Arya Vihara, “the monastery of the noble ones,” the property became a permanent home for Krishnamurti throughout his life as well as his place of death (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 47).

Beginning in August 1922, at the age of twenty-seven, Krishnamurti “was to be plunged into the intense spiritual awakening that changed the course of his life” (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 47). While at Ojai, he underwent an intense, life-altering transition, begun earlier in Holland, that was understood as a profound “transformative event that lasted for months and was to recur to the end of his life” (Lee Reference Lee2020: 8). This experience, called “the Process,” began as formal meditation, but moved on to involve “pain, nausea, hallucination, disembodied voices, and the apparition of religious figures” (Lee Reference Lee2020: 8). It contained moments of great beauty and clarity offset by periods of physical pain, even agony. He fell unconscious, conversed with nonphysical entities, and spoke from several personas. On occasion he talked as if observing himself and the Process from a distance and referred to himself in third person. In general, the import attributed to the Process was that Krishnamurti’s body was being prepared to serve as a receptacle of the higher consciousness of the Lord Maitreya (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 165–88) and was similar to a “classic description of arousing of kundalini” (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 59).

Krishnamurti’s report of his transformation of consciousness is consistent with other reports of mystical nondualism, wherein personality dissolves into communion with all else. In his words,

On the first day while I was in that state and more conscious of the things around me, I had the first most extraordinary experience. There was a man mending the road; that man was myself; the pickaxe he held was myself; the very stone which he was breaking up was a part of me; the tender blade of grass was my very being, and the tree beside the man was myself. I almost could feel and think like the roadmender and I could feel the wind passing through the tree, and the little ant on the blade of grass I could feel. The birds, the dust, and the very noise were a part of me. Just then there was a car passing by at some distance; I was the driver, the engine, and the tyres; as the car went further away from me, I was going away from myself. I was in everything or rather everything was in me, inanimate and animate, the mountain, the worm and all breathing things. All day long I remained in this happy condition.

This description of the result of the Process contains themes that appear in Krishnamurti’s teaching throughout his life.Footnote 1 Later, in a letter to Besant and Leadbeater, he elaborated, offering other themes of a recurring vision.

I was supremely happy, for I had seen. Nothing could ever be the same. I have drunk of the clear and pure waters at the source of the fountain of Life and my thirst was appeased. Nevermore could I be thirsty, nevermore could I be in utter darkness. I have seen the Light. I have touched compassion which heals all sorrow and suffering; it is not for myself, but for the world. I have stood on the mountain top and gazed at the mighty Beings. I have seen the glorious and healing Light. The fountain of Truth has been revealed to me and the darkness has been dispersed. Love in all its glory has intoxicated my heart; my heart can never be closed. I have drunk at the fountain of Joy and eternal Beauty. I am God-intoxicated!

Accounts of the Process by all witnesses concur that Krishnamurti’s awakening constituted a mystery, “a window into a world of great energy, love, and power” (Lee Reference Lee2020: 15). After the Process was complete – although sporadic incidents recurred for sixty-four years (Lee Reference Lee2020: 15) – another incident was to prove pivotal to Krishnamurti’s relationship to the Society. In 1925, as Nitya’s health was jeopardized by influenza in Ojai, Besant and Krishnamurti were assured that the Masters would see that the illness would be overcome, that “Nitya was essential for K’s life-mission and therefore he would not be allowed to die” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 219). With this assurance, Krishnamurti left the person dearest to him to travel to India. Yet, during the voyage, he received a telegram of Nitya’s death. With this immense loss and its consequent sorrow, “all physical references to the Masters ceased” (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 70). From then on, Krishnamurti “seems to have lost all faith in the Masters as presented by Leadbeater, though not in the Lord Maitreya and his own role as the vehicle” (Lutyens 1990: 58). This dissolution of trust in the Masters following Nitya’s death and the newfound perspective provided by the Process contributed to Krishnamurti’s growing distance from the authority structure of the Theosophical Society and its emphasis on the study and practice of occultism.

From a stance of overwhelming dissatisfaction with the Society, his talks began to emphasize the benefit of self-inquiry in the search for truth, a direction antithetical to the Theosophical structure of that day. Although he did not deny the existence of the Masters, in 1927 Krishnamurti began to say that the Masters and all other gurus are unnecessary, that everyone must find truth for himself. The following year, he told his audience “I hope that you will not listen to anyone, but will listen only to your own intuition, your own understanding, and give a public refusal to those who would be your interpreters” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1983: 14). He began to speak of the liberation of each person and that no one can give liberation to another; each must find it within one’s self.

In a rejection of all forms of spiritual authority, he disbanded the Order of the Star in August of 1929 (Jayakar Reference Jayakar1986: 78) at the international meeting of the Order in Ommen, Holland, stating,

I maintain that Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. … I do not want to belong to any organization of a spiritual kind. … If an organization be created for this purpose, it becomes a crutch, a weakness, a bondage, and must cripple the individual, and prevent him from growing, from establishing his uniqueness, which lies in his discovery for himself of that absolute, unconditioned Truth. … Because I am free, unconditioned, whole … I desire those who seek to understand me, to be free, not to follow me, not to make out of me a cage. … You are all depending for your spirituality on someone else. … No man from outside can make you free. … You have been accustomed to being told how far you have advanced, what your spiritual status is. How childish! Who but yourself can tell you if you are incorruptible? … For two years I have been thinking about this slowly, carefully, patiently, and I have now decided to disband the Order, as I happen to be its Head. You can form other organizations and expect someone else. With that I am not concerned, nor with creating new cages, new decorations for those cages. My only concern is to set men absolutely, unconditionally free.

Dissolution of the Order marked the beginning of Krishnamurti’s career as an independent teacher. His writings and addresses to audiences presented an increasingly clear message that scaled back his teaching to the individual, called for rigorous investigation of self, and rejected institutionalized forms of allegiance and belief as necessary for personal liberation. He spurned the “image of himself as a global keystone” involved with addressing the world’s problems at large, saying that “my purpose is only to awaken that knowledge, that desire to discover for yourself” (quoted in Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 179). His own role was defined as that of a “lamp, enlightening what was already there but could not be seen” (Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 179).

Leadbeater and other leaders of the Society rejected Krishnamurti’s message because it did not include homage to the occult hierarchy, institutions, or ceremonial practices in which these leaders officiated as the Teacher’s “self-appointed apostles,” even though such homage was contrary to all directives from the Teacher himself (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 210–17). Leadbeater also did not agree with the democratic tone of Krishnamurti’s message – that his teaching was, according to Leadbeater, “for the average man and not for one ‘who has our special advantages’” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1975: 278). Although Besant remained head of the international Theosophical Society until her death in 1933 and expressed sorrow over the split between Krishnamurti and the Society, she nevertheless continued to be his avid supporter, recognizing that his spiritual attainments and vision superseded her own (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 296). For his part, Krishnamurti retained an immense gratitude to Besant for her companionship and guardianship, consistently referring to her as Amma (mother) throughout his life, as he had since 1913 (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1983: 20).

2 An Independent Teacher (1929–1986)

At the age of thirty-four, Krishnamurti was no longer affiliated with any organization, nor did he claim personal authority to reveal the truth to anyone. 1929 marked the onset of bleak economic times globally, including the stock market collapse and the beginning of the Great Depression. It also signaled a continuing decline in the Theosophical Society’s membership. Having enjoyed an influx of members due to the discovery of the World Teacher and Krishnamurti’s charismatic appearances around the world, the Society began to turn in another direction in the late 1920s. The larger organization was in disarray, having suffered a series of disputes, scandals, defections, schisms, and lawsuits involving almost all the leaders – a persistent phenomenon that began with Blavatsky (Santucci Reference Santucci and Hanegraaff2006: 1114–23). In the years following 1929, the Society lost a third of its membership (Campbell Reference Campbell1980: 130).

It became clear that some had joined the Theosophical Society to be near the World Teacher, so that, with his separation from the Society, they felt comfortable resigning their membership as well. The Society’s leadership stood distant from the dissolution of the Order of the Star, maintaining that the Order was only one of many offshoots of the original Society and that the parent organization would not be affected (Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 189). In actuality, a central figure of the organization had divorced himself from its fold and, further, had undermined the legitimacy of its organization and beliefs. When addressing members of the Society, Krishnamurti stated that any organization, including theirs, based on religious hopes is not only irrelevant but also pernicious and encourages hypocrisy and deceit. Yet, he was invited back regularly to speak to meetings of the Theosophical Society while Besant was in charge and maintained an amicable relationship with the Society until his passing (Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 188–90). As Radha Burnier, President of the Theosophical Society in 1995, wrote in that year on the centenary of his birth, “The connection between J. Krishnamurti (Krishnaji as he was affectionately known) and the Theosophical Society was broken, not because he left – as many members believe – but because people were not ready to listen to a profound message given in terms they were not accustomed to hearing” (Burnier Reference Burnier1995: 104).

Krishnamurti’s audiences did not suffer such a decline. Financial support for the maintenance and propagation of his teaching shifted dramatically as he rejected the support of the Theosophical Society, disbanded the Order, and ended all financial connections with these organizations. A united core of students, some quite wealthy, were able to assure him a continued lifestyle of comfort. Some individuals left the Theosophical Society to follow the teachings of Krishnamurti; others retained their membership, while maintaining an allegiance to him; still others came upon Krishnamurti’s influence afresh, independent of his past, and became committed to the spread of his ideas. The result was a small but significant coterie of committed individuals who were not members of any organization and did not join any movement, yet supported Krishnamurti in several ways (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1983: 17–20).

Building on a publishing trust set up before dissolution of the Order, this coterie established foundations in England, India, Europe, South America, and the United States dedicated to furthering Krishnamurti’s teaching, creating schools to enact his teaching, sponsoring his personal appearances, and coordinating publication of his talks (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1983: 17–20). These foundations continue to collaborate today to fulfill these functions, but, according to Krishnamurti’s dictum, without any formal membership.

From 1929 until the outbreak of the Second World War, Krishnamurti traveled widely, consistently addressing the key themes of freedom, awareness, conditioning, love, and fear. During these years, his delivery became more polished, even as his message became more challenging. While he prioritized revolutionary change at the psychological level over social change, at the same time, he refused to support one nationality or one identity over another in a time of accelerating global conflict – both of which stances led to suspicion and criticism in a time of war. As the world confronted the reality of war, his appearances before public audiences grew more strained when he was questioned about his patriotism and national loyalties. Until the end of the war, he withdrew from public life and led a quiet existence in the Ojai Valley, where he gave occasional talks (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1983: 54–63).

Krishnamurti never married and was consistent in his warnings that marriage can restrict individual freedom, stultify relationships, serve as a “sanctification of possessiveness,” and preclude the possibility of a genuine relationship with another (Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 203). These views are of a piece with Krishnamurti’s concern that human love is confused with “pleasure, competition, jealousy, the desire to possess, to hold, to control and to interfere with another’s thinking” (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1969: 80). Although cautious of marriage, his message consistently focused on the importance of relationships among individuals, and he supported lasting commitments in relationships. Moreover, he did not extol the virtues of celibacy and asceticism, which he considered life-denying, artificially suppressive of natural drives, and potentially a source of power that is “separative and will not bring a comprehension of the whole” (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti2014: 51).

For twenty years, Krishnamurti carried on an intimate relationship with Rosalind Rajagopal, one of the few associates who witnessed the transformative events of the Process in Ojai in 1922–1923. In 1927 Rosalind married D. Rajagopalacharya (referred to as Rajagopal), who had known Krishnamurti since 1920, saw to the first publications of his talks, and occupied several roles, finally acting as his administrative and financial chief. Krishnamurti served as a doting father figure for the Rajagopals’ only child, a girl named Radha, who was to describe the relationship between her mother and Krishnamurti in print only after his death (Sloss Reference Sloss1991). According to Sloss, the two had a committed sexual relationship based on mutual love and respect, which was not upsetting to Radha’s father, Rajagopal. Publication of Sloss’s book prompted a reply by Mary Lutyens, one of Krishnamurti’s biographers, in which Lutyens affirms that “The physical relationship is not in dispute and should not come as a shock” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1996: 1). Even though Krishnamurti’s bond with Rosalind was not contrary to his teachings, the couple chose not to make their liaison public. The reasons for this secrecy have been the subject of conjecture and even derision, but acceptance of Krishnamurti and his message seems to have been little affected (Vernon Reference Vernon2000: 199–204).

From the end of the Second World War in 1945 until his death in 1986, at the age of ninety, Krishnamurti continuously taught his insights to audiences worldwide. These gatherings grew progressively from an exclusive Theosophical orbit to include all sorts of individuals from a host of nations. His appeal to personal inquiry without the aid of any organization, religion, or belief system and his defiance of all organizations as agents of tyranny and self-hypnosis varied little over the decades (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1954).

Krishnamurti died in his cottage in Ojai in 1986 from pancreatic cancer. Many of his admirers came to see him in his last months but were tactfully asked to leave. Only a few of his closest associates witnessed his last hours. Near the end, he called for a tape recorder to make a final statement, which he had to be assured would not be altered in any way. In short, he said,

[F]or seventy years that super-energy – no – that immense energy, immense intelligence, has been using this body. I don’t think people realize what tremendous energy and intelligence went through this body … and now the body can’t stand any more. You won’t find another body like this, or that supreme intelligence, operating in a body for many hundred years. You won’t see it again. When he goes, it goes. There is no consciousness left behind of that consciousness of that state. They’ll all pretend or try to imagine they can get into touch with that. Perhaps they will somewhat if they live the teachings. But nobody has done it. Nobody. And so that’s that.

According to his wishes, Krishnamurti was cremated in nearby Ventura, California, with no ritual performed and no memorial set up in his honor (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1990: 208).

3 The Context: Teacher and Teaching

Locating Krishnamurti’s teaching in terms of extant religious or philosophical systems – an exercise he would disdain – demonstrates an alignment with Asian nondual systems of thought that view ignorance as the central problem of humanity and self-realization as the primary spiritual goal of human existence. Conversely, his teaching is not aligned with Western monotheistic and dualistic emphases on salvation and an afterlife. Analogous to Gautama Buddha, Krishnamurti refused to refer to any deity or to any claims for reward or punishment in successive lifetimes. His emphasis on the cause of suffering and the psychological bondage that results from attachment to personal image, identity, and thought is also consistent with Asian, as well as Western esoteric, notions of the perils of conditioning to, and identification with, roles and images. While concentrating on the human condition in the moment, Krishnamurti refused to entertain conjecture about past and future, whether cast in terms of karmic debt, rewards and punishments, maya (illusion), or future bliss (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1954). He never mentioned deities or angels and, once detached from the Theosophical Society, never again taught the reality of the Masters. Although his first book, published under the name Alcyone, was a record of his tutelage by the Tibetan master Kuthumi, Krishnamurti says these were not his words, but rather the words of the Master who taught him (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1974a). From occasional references to rebirth or reincarnation made relative to his own life, one infers that he did not completely reject Asian cosmologies or ontologies. However, he never included reincarnation as a factor in his diagnosis of, or remedy for, the human condition. Instead, he emphasized individual instantaneous change in the moment, outside of time, and rejected evolutionary change – whether social, cultural, or spiritual – over time. To him, evolutionary change was not only not acceptable but also not possible (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1970).

Krishnamurti and his teaching are of a piece. He claimed that his teaching derived not from the study of religious or philosophical systems, but rather from a life of developed awareness that yielded an expansion of consciousness, personal freedom, and love. The first subsection that follows addresses the parallels between Krishnamurti’s life and his teaching, examining his refusal to identify himself as anyone other than an inquirer and his rejection of spiritual epithets applied to him. The final three subsections discuss themes that emerged in Krishnamurti’s life and became central to his teaching: living free from the known; self-inquiry without authority; and developing acute attention and awareness.

Life Experience Becomes a Message

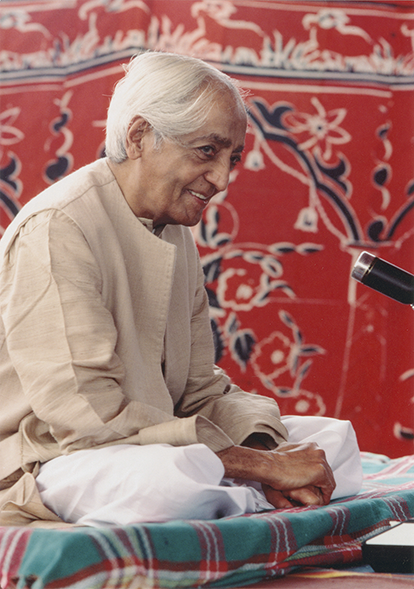

Although Krishnamurti bases his teaching in his life experiences, he does not identify his own experience as a legitimating factor or authority for validation of his message. He was born and raised in a traditional Brahmin Hindu family, yet he does not identify himself as Brahmin, Hindu, or even Indian. Throughout his life he remained strictly vegetarian, did not consume intoxicants, and practiced Hatha Yoga, although he repeatedly said that the reasons for these practices were not to obey any authority, to align himself with any religion, or to follow a prescribed regime. Highly self-disciplined himself, he did not advise anyone else to follow these practices and, in fact, shunned the notion of self-discipline in his teaching. He engaged in inquiry with scholars and teachers in a variety of religious and scientific traditions, yet he did not claim to follow, represent, or transmit any system or codified path. He had extraordinary experiences of illumination, yet he never advocated a search for transcendence or development of occult powers, stating instead that growth of consciousness is more appropriately found in acute awareness of everyday life. Krishnamurti’s message, thus, does not rely on the legitimacy of any external source nor his own status. Instead, he attributes his own understanding and the crux of his teaching to rigorous self-inquiry and development of awareness and attention (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 J. Krishnamurti, 1935.

Krishnamurti was particularly disdainful of the effects brought about by identification of an individual in terms of religion, nation, or culture. “When you call yourself an Indian or a Muslim or a Christian or a European, or anything else, you are being violent,” he said. “Do you see why it is violent? Because you are separating yourself from the rest of mankind” (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1969: 51–2). Krishnamurti applied this stricture to his own identity. When confronted by an educated Indian professional and told that his teaching was purely Advaita (nondual) Vedanta – one of the major philosophical schools of Hinduism – Krishnamurti described himself, in third person, by saying:

He denies the very tradition with which you invest him. He denies that his teaching is the continuity of the ancient teachings. … Any acceptance of authority is the very denial of truth, as he has insisted that one must be outside all culture, tradition and social morality. … He totally denies the past, its teachers, its interpreters, its theories and its formulas.

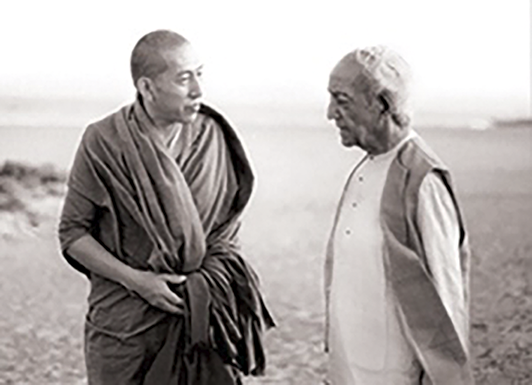

As Krishnamurti became a teacher in his own right, independent of any tradition or organization (see Figure 5), his addresses did not focus on the Brahmanical tradition that had saturated his early years, the complex cosmology left by Blavatsky as the foundation of the Theosophical worldview, or the preoccupations with the occult that inspired Leadbeater and Besant. Instead, he posited that personal transformation derives exclusively from individual self-inquiry and self-observation, absent any accompanying support from organizations, authorities, higher realms, or even fellow seekers.

Figure 5 J. Krishnamurti, 1968.

His teaching does not rely on a complex metaphysics, evolutionary scheme, or belief system as taught by the Theosophical Society. In fact, he doubted the efficacy of any beliefs or doctrine as productive of real change in an individual. Even though the Theosophical Society was a liberal, pan-religious movement founded on the intention to incorporate the highest teachings of all religions in its quest for truth – not restricted by nationality, tradition, or texts – Krishnamurti came to view the Theosophical Society as limited in its perspective and authoritarian in its procedures. That he examined his life independently and critically and came to doubt the utility of the Theosophical Society, even while under its tutelage, illustrates his assertion that sustained personal inquiry and freeing oneself from conditioning can effect real change in an individual. Krishnamurti distinguished his teachings as an inquiry into the human condition, independent of any allegiance or belief as to what constitutes an authority in spiritual matters, including, and perhaps especially, the Theosophical Society.

Nor did he rely on occult or psychic abilities to evoke altered states of consciousness or define the transcendent realm as an ideal to be reached, often considered validation of spiritual achievement. Instead, Krishnamurti stressed the necessity of expanding consciousness through acuity of awareness in everyday life.

Krishnamurti dissociated himself from the public mantle of World Teacher bestowed upon him by Leadbeater and Besant, but, curiously, he never rejected the notion that he was the vehicle of the World Teacher, the Lord Maitreya, who would inspire a new consciousness in humanity (Wessinger Reference Wessinger1988: 287; Lutyens Reference Lutyens1990: 83). Even when he learned that “a very early Tibetan manuscript contained a prediction that the Lord Maitreya would incarnate in a being with the name Krishnamurti” (Holroyd Reference Holroyd1991: 55), Krishnamurti stated that he was skeptical. He seemed to consider the “enigma of his origins and his identity irrelevant to the truth of the teachings” (Holroyd Reference Holroyd1991: 55). Krishnamurti’s own words attest to his understanding that his selection was providential, but that the expectations and projections contained in the narrative and organizational structures of the Theosophical Society were inconsistent with, if not contradictory to, his interpretation of the role of World Teacher. In a letter to his enduring confidante Lady Emily Lutyens, mother of a major biographer, he wrote:

You know, mum, I have never denied it [being the World Teacher], I have only said it does not matter who or what I am but that they should examine what I say, which does not mean that I have denied being the W. T.

In biographer Lutyens’s words, “He was never to deny it” (Lutyens Reference Lutyens1990: 83). Curiously, Krishnamurti accepted the ontology (and presumably accompanying prophecies) of a World Teacher, who would enter the world to provide insight into the evolution of consciousness, yet declined the public mantle of World Teacher. This paradoxical situation in which he offered a teaching, a message, without seeking recognition of himself as a source of wisdom or authority is the basis for the epithet “non-guru guru” (Balasundaram Reference Balasundaram2012: 7–8). He was a teacher and guide, and thus, by one interpretation, a guru; but he did not assume the authority usually attributed to a guru, thus, by another interpretation, he was a non-guru. He was quite clear about the role of teacher that he assumed and the role of guru that he rejected:

I do not demand a thing from you, neither your worship, nor your flattery, nor your insults, nor your gods. I say “this is a fact; take it or leave it.” And most of you will leave it, for the obvious reason that you do not find gratification in it.

Several themes that emerged in Krishnamurti’s life became foundational to his teaching: freedom from conditioning and the known; self-inquiry without authority; and developing acute attention and awareness. His entire teaching remained centered around these basic processes.

Freedom from the Known

With the stated goal of making all of humanity absolutely, unconditionally free, Krishnamurti invited those who listened to him to observe their inner selves, including the movement and functions of thought. With each audience, Krishnamurti inquired into the basic nature of humanity and emphasized the necessity of becoming aware of one’s conditioning, identification with one’s position and thought, and the consequent bondage to fear and time.

Participation in psychological thought – that is, activity of the mind attached to a personal identity – inevitably conditions an individual to live in the past, through constructions of thought that constitute knowledge, the known. Individuals live as “second-hand people” (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1969: 10), meaning that they accept the knowledge derived from their own thought or from some authority, whether text or teacher. As second-hand people, individuals learn to revere knowledge presented through thought and become unable to perceive what is present and observable outside thought, in the moment (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1999). They live in an illusory world of notions about self, without grasping the truth of self. They are conditioned. They are not free.

Krishnamurti’s terminology regarding the known and truth is quite specific. To him, the known is made up of thought and memory transferred from one person to another or constructed in one’s mind. The unknown is the extent of one’s conditioning that cannot be readily observed by the psyche and certainly not transmitted from one person to another. Without question, many “truths” exist as facts in the collective of society. These truths are termed by Krishnamurti as the known. But the truth of one’s conditioning is idiosyncratic to each person and lies outside these collective truths. Thus, the truth that one seeks to find about oneself is not the known, but rather the unknown and must be discovered anew by each person. Further, this truth cannot be apprehended by thought, whether transferred from another or constructed by oneself. What is needed is to be free from the thought and memory of the known to confront the unknown, the truth of oneself, outside thought (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1969).

What is needed is to escape the tight grip of conditioning and psychological thought to experience freedom in the mind. Instead of finding guidance through imitation of respected authorities or self-hypnosis, one can investigate through self-inquiry the ways in which one is not free (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1999: 17–18). Understanding one’s lack of freedom requires understanding the edifice created by psychological thought, brought about through observation of self in the present moment, without interference from authority, identification, or conditioning, all of which divide the personal psyche and separate individuals from each other (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1999: 113). To be free one must die to the “known” to discover for oneself truth, which is limitless, unconditioned, and unapproachable by any path whatsoever (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1969: 9–33).

According to Krishnamurti, awareness of the unknown in oneself requires a whole and immediate shift in the moment – a revolutionary change that cannot be wrought incrementally through progressive steps. This seeing of oneself that he envisions brings an awareness of the whole of oneself that allows a new understanding of being to flower, not dependent upon psychological thought, conditioning, or time. With this seeing, an individual is free from identification with any role or position, which distorts observation of the truth of the situation. When one sees oneself in the moment outside conditioning or identification, one discovers another state of consciousness and awareness without limit, another intelligence beyond intellect. But this discovery occurs only through “not knowing,” through inquiry into what cannot be known through psychological thought.

When identification as an observer is absent, one can observe without fear, desire, suppression, or denial. A radical transformation occurs “if there is no background, if there is no observer who is the background” (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1999: 114). In the very process of observing, change occurs. In this way, one can “be a light to oneself” (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1999: 2).

Krishnamurti teaches that, because all religions and systems of redemption – whether engaged in the goal of salvation, enlightenment, liberation, or self-realization – are the products of thought, they must be rejected as the source of insight into oneself. Any promise derived from a system of thought can only be an illusion, so Krishnamurti refused to delineate a cosmology, any soteriological system, or any tenets of belief. Once, when asked about astrology and reincarnation, Krishnamurti replied: “It is not a matter of belief; belief is never alive – never real. Reincarnation is a fact, but you have to discover it for yourself, in your life, and not from me or a book” (Lee Reference Lee2016: 70–1).

In essence, Krishnamurti’s teaching lacks any trappings of established traditions, including belief systems, cosmologies, status hierarchies, and authority structures. To Krishnamurti, individual transformation in the moment occurs through developed inquiry, sustained attention, and self-examination, processes that resemble a number of spiritual approaches – such as nondual practices, Indigenous spirituality, and esoteric exercises among others – but are identical to none. Attempts to discover resonances between Krishnamurti’s teaching and extant systems of thought and practice offer multiple themes, such as observation of the natural world, the unity behind all diversity, and a call for individual responsibility. Yet, these resonances stop short of any resemblance to legitimizing institutions or authoritative sources found in these systems. Rather, the moment of sincere self-observation is the only verification, the only legitimation, of Krishnamurti’s ideas that he would sanction.

Self-Inquiry without Authority

Krishnamurti asserts that transfer of knowledge from experts or texts to an individual’s memory is not genuine knowledge of self. Just as a professor of Buddhism does not have the consciousness of the Buddha, one cannot study the ideas of others and gain insight into oneself. Such understanding derives from self-inquiry, which alone produces direct, personal perception of the truth of oneself. Whereas ordinary knowledge is gained through the intellect, through cognition, real self-knowledge resides at the level of perception, which includes intellect and mind, but is a holistic event that includes all senses and the body, unmediated by psychological thought. Perception is a spontaneous seeing of oneself, rather than a cognitive process of thinking about oneself. Seeing oneself in the moment cannot be shared among individuals, but must be discovered by each person anew (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1972).

To Krishnamurti, knowledge about oneself gained through perception requires an orderly mind, open inquiry, and intelligence, all of which are destroyed when one depends upon an external authority. Further, making a teacher or a tradition into an authority destroys inquiry and intelligence; direct knowledge about oneself is the only truth that can change consciousness. When one observes oneself sincerely without judgment, one awakens an intelligence and develops an observing consciousness that can perceive how one is conditioned throughout life to identify as a separate individual with memory and past knowledge of one’s own. Through inquiry, one sees that what is deemed “one’s own” is a congeries of conditioned responses to experiences that have become habitual and with which one identifies. Further inquiry reveals that this conception of oneself – the ego – is borrowed from outside oneself and is thus illusory and riddled with error. The teaching, therefore, is not to study and understand Krishnamurti’s perspective but simply to perceive one’s own truth in oneself and how one’s consciousness operates, an exploration that must be conducted on one’s own (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1954).

One particularly tenacious obstacle to direct perception of the truth of oneself is negative emotions, which Krishnamurti labels disorder. He says that when one sees this disorder directly, the actual seeing itself changes consciousness. Transformation of consciousness is not produced through an exercise of will or through control of one part of self over another part, but rather, through the actual perception of the disorder in oneself. He asks that one become aware of how disorder, whether irrationality, jealousy, fear, or competition, lives in oneself. Using thought to identify, evaluate, accept, or reject disorder will not eradicate disorder because using the mind in the process of identification enhances the negative emotion that is associated with a role. Rather, seeing the disorder in the moment of awareness, independent of thought, changes the situation immediately; disorder gives way to order. With perception of the uselessness, even danger, of fear, greed, ambition, or conflict, these elements of disorder lessen their hold on the psyche and order emerges from disorder. Freedom from the unconscious habitual bondage of conditioning then results in transformation of consciousness (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1954).

Awareness and Attention

The crux of Krishnamurti’s teaching is to discover and then cultivate an attention that opens to an awareness that is pure, empty, and not filled with the contents of the mind. Of primary importance is to gain insight into one’s own consciousness through direct perception of one’s personal and unique bondage to mechanical and habitual modes of existence. Attending to the nature of the self allows direct observation of how one is bound ceaselessly to thought, to the remnants of memory, and assumptions built on these remnants. To Krishnamurti, the self, by its very nature, is divisive, separating and isolating an individual from others and creating division and disorder in the psyche.

By the self, I mean the idea, the memory, the conclusion, the experience, the various forms of nameable and unnameable intentions, the conscious endeavour to be or not to be, the accumulated memory of the unconscious, the racial, the group, the individual, the clan, and the whole of it all. … Experience strengthens the self, because reaction, response to something seen, is experience.