Introduction: Rus, Russia, Ukraine

Numerous scholars have now made the case that the Enlightenment period helped to shape our modern perception of the past. Whether this was Anthony Kaldellis talking about the creation of “Byzantium” or Larry Wolff discussing the Invention of Eastern Europe, one can turn to good scholarship to understand what happened 300 years ago and its effects on our understanding of history.Footnote 1 What is missing though is our integration of that material into our modern understanding of why that matters. The case of medieval Rus and modern Ukraine is an excellent one to use to explore what happened to create a separate medieval East and West and why that matters in the present.

A year before Russian President Vladimir Putin’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he published a piece entitled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.”Footnote 2 In that article Putin repeated the long-standing belief that Russians were Great Russians and Ukrainians were simply Little Russians. To do this, he used history as his guide. He did not just go back to the seventeenth century when Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich was the first to use the title “Sovereign of Great, Little, and White Russia.” Instead, he went all the way back to the Middle Ages and the medieval kingdom of Rus to demonstrate that the Ukrainians and Russians were the same people. In particular, he quoted the Povest’ vremennykh let (often translated as the Tale of Bygone Years), the earliest Rusian source, to say, “Let [Kiev] be the mother of all Russian cities.”Footnote 3 Which is not that different from the only English translation of that source: Oleg “declared that [Kiev] should be the mother of Russian cities.”Footnote 4 This translation, published in 1953 but prepared earlier, is titled The Russian Primary Chronicle. And here we can see elements of the problem quite clearly. Both Vladimir Putin and the translator of the chronicle are stating that the history of the ninth-century polity and the early twelfth-century source are all Russian. Such a label makes it much easier to elide the medieval kingdom of Rus into the modern country of Russia and erase anyone else’s claim to the medieval past of that region. A more accurate translation of the same phrase from the chronicle would be, “Let this [Kyiv] be the mother of the towns of Rus’.”Footnote 5 Taking away the idea that medieval Rus was Russia is one step, but a large one, in attempting to shift our perception of medieval and modern Europe.

However, it is worth examining how medieval Europe became so divided, and why, to help us better understand and move away from those perspectives. As noted earlier, the Enlightenment played a key role, especially in regard to Orthodoxy. Orthodox Christianity was viewed as even more outdated, old, and traditional than Catholicism, which was more common in the lives of the Enlightenment thinkers. Many have traced the anti-religious streak back to Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, with John Arnold stating, “Gibbon has bequeathed to us a particular way of looking at religious credulity as the opposite of Reason and thus as a threat to civilization, a view which tends to recur in current debate.”Footnote 6 Gibbon’s later eighteenth-century writings did not appear in a vacuum and is contextualized with numerous instances where Orthodoxy was treated as not just the enemy of Reason, but of the Western order, as well. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, broad sheets published in German cities told about the atrocities of the Russians using identical language – in fact the broadsheets were the same, with only the perpetrators replaced – as when they discussed the Ottoman Turks.Footnote 7 Similarly, after Peter the Great’s victory at Poltava in 1709, an official of King George I stated that “Germany and the entire North have never been in such grave peril as now, because the Russians should be feared more than the Turks … and are gradually advancing closer and closer to our lives.”Footnote 8 Long gone were the days of any Christian unity, in its place was an identification by Western Europeans that Orthodoxy was as much of a threat, if not more, than the dominant Islamic empire in Western Afro-Eurasia.

Even if we advance to the twentieth century, the division of Europe with Orthodoxy at its heart is not just still present but increasingly codified. J. B. Bury, not coincidentally a scholar of Gibbon, divided his massive Cambridge Medieval History project such that eastern Europe was allocated into one volume. He explained his rationale quite clearly in his introduction:

This exception to the general chronological plan of the world seemed both convenient and desirable. The orbit of Byzantium, the history of the peoples and states which moved within that orbit and always looked to it as the central body, giver of light and heat, did indeed at some points touch or traverse the orbits of western European states, but the development of these on the whole was not deeply affected or sensibly perturbed by what happened east of Italy or south of the Danube, and it was only in the time of the Crusades that some of their rulers came into close contact with the Eastern Empire or that it counted to any considerable extent in their policies.Footnote 9

For Bury, Europe may exist as a geographic entity, but medieval Europe largely refers to western Europe and eastern Europe is relegated to a Byzantine sphere of influence. Dimitri Obolensky took this a step further when, in the 1970s, he codified the idea of a Byzantine Commonwealth.Footnote 10 The organizing principle of Obolensky’s commonwealth was the tacit acknowledgment of the Byzantine emperor’s authority over the whole of Orthodox Christendom. Thus, he does not include such areas of Byzantine influence as Venice, Sicily, or the Caucasus; because they do not fit into the Orthodox-centered scheme which he has created. Garth Fowden, who took classes with Obolensky at Oxford, makes this quite clear when he notes that Obolensky’s commonwealth constituted, “the Chalcedonian Orthodox world of Slavic Eastern Europe.”Footnote 11 A combination of the foregoing ideas has led us to the modern world of medieval studies where there exists a “medieval Europe” which comprises largely western Europe, though Iberia, Scandinavia, and Central Europe are making inroads into this territory; and a Byzantine world which includes the Orthodox Balkans and Rus. Whether one looks in textbooks, job ads, or conference programs, one can see this pattern replicated.

But how then does this relate to Rus, Ukraine, and Russia? The Russian narrative of history was codified by Vasilii Kliuchevsky in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in his famous History of Russia. These books inspired a generation of historians and Kliuchevsky himself was, in the words of his biographer, “Russia’s most distinguished historian and whose teaching, writing and training of young scholars have markedly affected the way Russians and others view Russia’s past.”Footnote 12 Kliuchevsky’s History of Russia was translated into eleven languages, including English, and his students taught Russian history across Europe and in North America, thus his ideas spread widely. His view on Rus was that it was simply Russia and in his volume 1, the material is largely related to Rusian–Byzantine ties.Footnote 13 There are no mentions of the manifold dynastic marriages which connected Rus throughout Europe in this period, nor the breadth of religious and trade relations. When non-Rusian or Byzantine influences are included, they are negative. In fighting against the “barbarians of the steppe” Rus held “the left flank of Europe. Yet this historical service cost her dear, since not only did it dislodge her from her old settlements on the Dnieper, but it caused the whole trend of her life to become altered.”Footnote 14 In addition to a lack of Rus, there is also a lack of Rusians in his narrative. “He ignored the existence of separate Ukrainian and Belorussian nationalities and cultures and those who proclaimed it: in his judgment, these peoples were Russians.”Footnote 15 Moreover, in later volumes, he dealt with the Russian conquest of the lands of Ukrainians and Belorussians as a historical inevitability akin to manifest destiny, often under the label of the “gathering of the Rus lands.” His views codified the belief of a Russian world that comprised eastern Europe and was connected to, if not descended from, the Byzantine Orthodox world; and created the basis for this to be taught and perpetuated until the present day.Footnote 16

Kliuchevsky’s narrative has been called the “traditional scheme of Russian history,” and this is accurate, but not inclusive.Footnote 17 Due to the popularity of the “traditional scheme,” Russian history writ large – which is to say eastern European history or Orthodox European history – became its own field and thus could be safely excluded from other regions, such as medieval European history. A cursory glance at a popular medieval Europe textbook will show the place of Rus, and other Orthodox polities:

“The ‘border’ that divides Catholic from Orthodox in the Balkans is today roughly the border between Croatia (Catholic) and Serbia (Orthodox). When we think about the wars in the Balkans that occurred in the 1990s, it is important to remember that many of the divisions are at least in part along religious lines – Catholics, Orthodox, and Muslims (remember that Ottoman Turks ruled the southern Balkans for more than four hundred years beginning in the last century of the Byzantine Empire) – that were first established during the Middle Ages.”Footnote 18

“Like the Balkan Slavs, the Russians received their religion and much of their culture from Constantinople. Indeed, after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the Russians began to think of themselves as heirs to the Roman Empire: just as Rome had given way to Constantinople, so now has the torch passed to the third and final Rome, Moscow”Footnote 19

To conclude their narrative, the authors make clear their perspective on the division in Europe and its consequences by suggesting that “When we think of problems and misunderstandings within Europe today, we in large part think of tensions and conflicts that exist along the lines of Western and Byzantine spheres of influence, for example, the line between Poland and Russia or that between Croatia and Serbia.”Footnote 20 For these authors, as well as for many authors not cited here, the division between Latin and Orthodox in the middle ages are replicated in the problems of the modern world.

A division in Europe based on historical and religious divisions can be seen in current political issues. The United Nations definition of the term “Eastern Europe” exemplifies the issues under discussion: “that part of the European continent that has been ‘under Byzantine and Orthodox influence, which has only randomly been touched by an Ottoman impact, but significantly shaped by Russian influence during the Russian Empire and in the Soviet period’.”Footnote 21 The eastern part of Europe is no longer just a geographical definition, but a categorical one which is based, in large part, around Orthodoxy. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was created in the wake of World War II, and its mission was to oppose the Soviet Union and its expansion. Yet, the first NATO Secretary General, Lord Ismay, colloquially stated the organization’s purpose as “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.”Footnote 22 Apart from the fascinating comments about Americans and Germans, the focus for Lord Ismay was not the Soviet Union, but Russia and the Russians – perhaps creating a link with the quote from the official of George I two hundred years earlier. Lord Ismay’s interpretation of the organization’s mission was implicitly ratified in the years after 1991 when the fall of the Soviet Union did not mean the disbanding of NATO; instead, it expanded. The expansion of NATO brought it closer and closer to the Russian border, despite multiple warnings from Boris Yeltsin, Putin, and various Russia experts that this was seen as threatening.

We could take our argument one step further and unite the themes of Orthodoxy and European identity. The European Union (EU) comprises twenty-seven member states, of which three are majority Orthodox countries (Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania). The other majority Orthodox countries in Europe are Belarus, Moldova, North Macedonia, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the Orthodox countries comprise the majority of Europe which is not included in the EU. If one includes the European Economic Area (which adds numerous western and northern European countries), one can see the outliers are all Orthodox countries. Thus, the logical conclusion is that the territory of the European continent which we traditionally label “Europe” is largely non-Orthodox, while the rest, which is typically labeled “Eastern Europe” is Orthodox; creating a frame which has caused problems for Ukraine’s ability to join the EU, among many other issues.

Figure 1 Map of Europe designating Orthodox countries not in the EU (red), the European Union (green), and the Orthodox countries in the EU (purple).

Education is a blessing, but an incorrect understanding of history can create problems. Medieval history matters for so many reasons, but one is that it sets expectations for modern perceptions. A medieval Europe that is inclusive of Rus and thus stretches from the Ural Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean will help to shift our perception of Europe not only in that period, but in our own.

The sections in this slim volume will attempt to do a broad task, elucidate the history of the kingdom of Rus and its relationship with the rest of Europe. Section 1: “Situating Rus” is intended as a brief introduction to the foundation of the kingdom, some of its early actors and its relationship to the world around it, both in history and in historiography. Section 2 is on religion and thus tackles the issue highlighted in the Introduction, the conversion of Rus to Christianity. Instead of a traditional picture of Orthodox dominance, this section will highlight the position of Rus within the broader Christian world. Section 3 examines the kingdom of Rus itself with a specific focus on governance, both top down and local. This is an important topic in the historiography because Rus’s decentralized government has often led to perceptions of them as an “other.” Section 4 brings the world back in and discusses the place of Rus in Europe. Far from the traditional “Route from the Varangians to the Greeks,” Rus was tied in to most corners of Europe through dynastic and other relations. The sum total of this short overview of Kyivan Rus in Medieval Europe will demonstrate the importance of accurate representations of history, both for its own sake, as well as for our understanding of the world around us.

1 Situating Rus

Rus seldom appears on modern maps of medieval Europe. Instead, if the map is comprehensive, it may use “Russia” to label that part of the eastern Europe; while if the map is not, it will most likely leave the area blank, or occlude it behind the key explaining what is going on in Western Europe. Regardless of the historiographical issues embedded here, we need to begin with setting the stage for where Rus was, what it was, and how we know anything about it before we can properly contextualize it in regard to medieval Europe as a whole.

The kingdom of Rus was founded by Scandinavians who explored the eastern European river systems. Unlike expansion westward from Norway, which is often described as requiring the dual advances of keel and sail; going east around the Baltic was a much simpler task which could be, and was, accomplished by oared boats.Footnote 23 Evidence for amber and fur trade, and as loot from raids, comes from an earlier period than what we see for the start of the Viking age. The traditional, and still dominant, explanation for the expansion of Scandinavians into eastern Europe is focused on the acquisition of silver. There were no native silver deposits in Scandinavia or in northeastern Europe, but by the later eighth century, silver began appearing in the Baltic. The source of silver were dirhams, Islamic coins from the Abbasid Caliphate. Those coins made their way up the Volga River via trade with the Khazars, Bulgars, and local Slavic and Finnic populations. Thomas Noonan, who studied the numismatics of Rus extensively, suggests that 36 percent of the silver coming into eastern Europe in the period 780–830 was exported to the Baltic.Footnote 24 This amount increased each decade subsequently and in the early ninth century finds begin to appear along the Dnieper River route as well, largely on the left bank (eastern side) of the river. Noonan concludes that “once it became known that Ladoga [a town in the north on Lake Ladoga] was the chief outlet for the export of Islamic dirhams to the eastern Baltic, peoples from all over the Baltic came to Ladoga to obtain these coins.”Footnote 25 One can see the impact of that silver in the rise of Birka and Gotland in the ninth century.Footnote 26 In addition to silver, eastern Europe was a source for other goods such as the aforementioned amber and furs, as well as slaves.Footnote 27

Scandinavians came into eastern Europe searching for these goods, but they also made a life there. In the earliest excavated settlement layer from Ladoga, dated 750–830, numerous goods with ties to Scandinavia have been found, including Frisian style bone combs, wooden toy swords of Frankish style, and leather shoes which can be found around the rim of the Baltic as in Norway.Footnote 28 Even farther afield, near Lake Kubenskoye (700 kilometers to the east of Ladoga) tenth-century finds of glass beads are similar to what is found in Birka, in both style and quantity.Footnote 29 In fact, Ingmar Jansson notes that “Mainland Scandinavian artefacts are abundant, found in settlements, graves and hoards throughout the land of Rus – in political and economic centres and also in some rural regions.”Footnote 30 All of which creates a solid basis for the interactions between Scandinavians and eastern Europeans in the material record.

Textual sources for the Scandinavian presence along the eastern European river systems are more complicated. Viking raids on Anglo-Saxon England, Ireland, and the Carolingian territories are all well recorded by contemporaries, or those writing slightly later. This profusion of sources is due to a literate populace being raided, often monks in monasteries, as well as the widespread network generated by the Northumbrian renaissance. Eastern Europe was not Christianized, and thus, we have no monasteries to raid or monks to write about such raids. For early textual sources we must rely on those preserved in Arabic and Greek, as the Scandinavians reached the Caspian and Black Sea regions, and a few in Latin typically about trade. The Arabic sources provide us with the earliest textual glimpse of Rus. Ibn Khurradādhbih was the director of the Abbasid intelligence service in the late ninth and early tenth centuries. In the middle of the ninth century, he wrote a report about the Radhanite merchants traveling through eastern Europe and into Abbasid territory. Within that report is a section on Rusian merchants. He describes them as “one of the Saqaliba people” which is a word typically used for Slavs, and they are from the farthest reaches of that land, implying the north.Footnote 31 Early in the next century, Masʻūdī says that “the Rūs are many nations, divided into different groups.”Footnote 32 And then relates that they travel “far and wide, trading with al-Andalus, Rome, Constantinople and the Khazars.” Relations with the Khazars, a raid upon whom Masʻūdī records, also provide an entry point for Arabic sources on Rus. Istakhrī, writing in the mid-tenth century, suggests that “there are three sorts of Rūs. One sort lives near Bulghār and their king dwells in a city called Kiev; it is larger than Bulghār. Another sort live further away; they are called Slovenes [Salāwīya]. And there is a sort called Arthānīya; their king lives in Arthā and the people come to trade in Kiev.”Footnote 33 Trading, especially along the river systems, is highlighted by Istakhri, especially in sable pelts.

Greek sources also begin in the mid-ninth century with a report by Patriarch Photius regarding an attack on Constantinople by a “Scythian tribe,” “An obscure nation, a nation of no account, a nation ranked among slaves … ”Footnote 34 Scythian is a generic term used in the medieval Roman Empire to describe those to their north, across the Black Sea. Photius does refer to “Rhos” in the titles of his homilies (III and IV), but not in the text. Later in the 860s he uses “Rhos” in an encyclical to the other patriarchs, telling of a mission to convert them, and referencing the 860 attack on Constantinople.Footnote 35 This same information is included in the text of Theophanes Continuatus, who wrote in the middle of the tenth century, possibly under the sponsorship of Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos.Footnote 36 It is also included in John Skylitzes, writing in the eleventh century.Footnote 37 The possibility of a ninth-century conversion of Rus has been speculated upon by modern authors, but it is difficult given the lack of other sources and the possibility of a repetition of information in three Greek sources.Footnote 38 In the tenth century, Rus and its rulers come more into the view of the medieval Romans. In 967, Emperor Nikephoras II Phokas requested assistance from Sviatoslav, the ruler of Rus, against the Bulgars.Footnote 39 Both Leo the Deacon and Skylitzes record the various battles of this campaign and have a good deal of information about Sviatoslav and the Rusians who are referred to as Rhos, Scythians, Taurians, and Tauroscythians.

The Latin sources are thin for this early period of the history of Rus. In the early tenth century, the Byzantine emperor Theophilos sent a group of “Rhos” to Louis the Pious because they could not return home the way they arrived.Footnote 40 After an investigation, Louis the Pious pronounced them to be Swedes, a group which he knew quite well from dealing with Scandinavian raids, and the presence of Danes at his court, such as Harald Klak. According to a new reading by Ildar Garipzanov, it is also possible that they named their ruler as Hakon, a decidedly Scandinavian name.Footnote 41 Latin sources also record the presence of the Rusians as traders, akin to what the Arabic sources record. The Raffelstettin regulations of the early tenth century mark the presence of Rusians in the middle Danube region.Footnote 42 Largely they traded wax, horses, and slaves and continued to be present in other early tenth-century trading regulations, increasing their identification as traders on an east-west route, not just a north-south one.

Local sources come into the picture rather late. The earliest chronicle source produced in Rus dates to the end of the eleventh and early twelfth centuries. It is known as the Povest’ vremennykh let (PVL), after its opening phrase. This chronicle begins with the biblical flood, proceeds to the foundation myth for Rus in the ninth century, and then entries become more common in the second half of the tenth century. One quite interesting aspect of this source is the likely interpolation of two treaties between Rus and the Roman Empire, each of which followed raids on Constantinople.Footnote 43 The treaties are formulaic in organization, but include specifics on the Rusians, their gods, and their names, indicating a good knowledge between the two groups and possibly providing another early source for Rus.

Having established the early source base for Rus, we can say comfortably that the Rusians were Scandinavians who explored the eastern European river systems and occupied existing towns, dominating local populations, and trading with the Khazars, Bulgars, Romans, Germans, and others. But where do we get this name of Rus? The traditional explanation is based around translation and transmission. The local Finnic speakers on the Baltic coast referred to those coming from Scandinavia as “rowers” (ruotsi); as noted earlier, they did not need the advancement of sails to reach the eastern Baltic. When those Finns guided (willingly or otherwise) the Scandinavians into the interior they called them not Scandinavians, Swedes, or any other ethnonym, instead using their own name for them – ruotsi. The Slavs dropped the “ts” into a simple “s” and called those who came “rusi.” Over time, the ending became softened and is now indicated by a soft sign (rendered in English by a ′), thus Rus′. Though for ease of use, I have excluded the prime and simply use Rus for the place and Rusian for the people throughout.

Normanist Controversy

The beginning of the previous paragraph elides the fact that some scholars do not, in fact, agree that the Rusians were Scandinavians. The controversy between those who do and those who do not believe this has come to be called the “Normanist Controversy,” as in were the Rusians Scandinavians (Northmen, Normans)? A brief overview of the controversy is essential to contextualize the history and historiography of Rus.

The 862 entry in the PVL states that the Slavs, having “driven the Varangians overseas,” then invited them back in because they could not rule themselves.Footnote 44 Accordingly, they sent to the Rusians for a leader. As for who the Rusians were, the chronicler takes pains to point that out, saying, “For that’s the way these Varangians called themselves, Rusians: as now others are called Swedes, and others Normans, Angles, still others Goths … .” The chronicler is situating the Rusians “overseas” among other Scandinavian peoples such as the Swedes. Similarly, the two treaties interpolated into the PVL between Rus and the medieval Roman Empire includes the signatories; for the 912 treaty, following the imperial names it says, “we of the Rusian nation, Karl, Ingjald, Farulf, Vermund … ” and so on.Footnote 45 The names are almost entirely Scandinavian and they identify themselves as Rusian, solidifying that link. Outside of Rus, we see a similar situation in the Annals of St. Bertin where envoys from Rus come to the court of Louis the Pious and he identified them as Swedes, further linking Rusians and Scandinavians.Footnote 46 The case in primary sources seems clear.

In the eighteenth century, however, Mikhail Lomonosov, one of the earliest Russian, rather than German, scholars in the Russian Academy posited a new theory, one grounded in politics. His suggestion was that the Rusians were autochthonous Slavs who were from the Ros River region.Footnote 47 The idea that the Rusians were Slavs rather than Swedes was incredibly important in the context of contemporary politics as Peter the Great had recently fought the Swedes for twenty years in the Great Northern War, and they had been a primary rival for more than a century prior. Russia’s attempts to link itself to the Kyivan Rus past meant that the foundations of Rus needed to be the foundations of Russia. Thus, if the Slavs could not govern themselves and had to invite in Scandinavians to rule over them, as the PVL states in 862, the contemporary ramifications were a negative portrayal vis-à-vis the ongoing conflict with the Swedes and in regard to the ability of Russia to stand alone as an empire in Europe. Lomonosov’s ideas birthed the Normanist controversy. The Normanist position has been consistent and has been stated here. The anti-Normanist position begun by Lomonosov has changed numerous times over the last two hundred years, as various ideas were disproven by textual or archaeological evidence. The persistence of the anti-Normanist position is largely linked to government sponsorship under Imperial, Soviet, and modern Russian regimes which aim to strengthen their idea of nation via an articulation of an independent past.Footnote 48 The past, as we should know, is not only another country, but does not exist to validate or legitimize modern polities or their dictators. That the Rusians were Scandinavians is evident in the extant sources and should be able to be discussed without political interference.

A Kyivan Kingdom

The semi-mythical Riurik was succeeded by Oleg, Helgi in the original Scandinavian. The PVL is clear that Oleg belonged to Riurik’s family, but Riurik also entrusted his son Igor (Ingvar) to him as well, “as he was very young.”Footnote 49 Oleg and Igor are historical characters who appear in sources beyond the PVL, unlike Riurik; however, their relationship to one another and to Riurik is unclear. Oleg ruled until 913 when Igor succeeded him, which, if Igor was only one at the time of Riurik’s death, would make him thirty-five years old when he is able to succeed.Footnote 50 Igor rules until his death in 945, on a raid, at the age of sixty-seven. At Igor’s death, his wife Olga (Helga) ruled as regent for their young son Sviatoslav, who came of age and began to rule ca. 964; nineteen years after his father’s death. Of course, none of this is impossible, but it does seem unlikely that Oleg ruled as regent, the implication of the chronicle, for thirty plus years, well after his ward’s age of majority. That Igor only had one son, and that in his mid-60s, and the son stayed under his mother’s rule until he was at least nineteen, if not older. More likely is that the chronicler writing in the eleventh century was attempting to make sense of earlier stories which contained numerous early rulers and to put them into some kind of an order to help ground the ruling clan of Rus.

Oleg has multiple claims to fame, but a key one here is his link between the two bases of Rus. Venturing south from the Rusian base near what will become Novgorod, in 882 he took the city of Kyiv on the Dnieper. Kyiv at the time was ruled by two Scandinavians, Askold and Dir.Footnote 51 The PVL ascribes the Rusian attack on Constantinople in the 860s to them, including Photius’s dispatch of the Rusians by dipping the hem of a garment of the Mother of God into the Black Sea, causing a storm to rise up and wipe out “the godless Rusians.”Footnote 52 The PVL’s account of this attack is much different than the attacks led by Oleg or Igor in the tenth century, both of whom were also “godless Rusians.” The point being made by the chronicler is articulated by Oleg when he confronts Askold and Dir in 882: “’You are not rulers nor even of a ruling family, though I am from a ruling family’ and bringing forward Igor ‘and this is the son of Riuirk.”Footnote 53 Reading between the lines of the chronicle account we see numerous Scandinavians in eastern Europe, not just one particular family. Oleg’s claim to Kyiv is based on force, but the chronicler includes the justification of his being from a ruling family and his possession of Riurik’s son, Igor; even though Igor would not come to rule for another thirty-one years. Denigrating Askold and Dir as ignoble also allowed the chronicler to explain the failure of the Rusian attack on Constantinople in the 860s, situating Rus in wider medieval history, but also not denigrating his sponsors who claimed descent from Igor, if not Oleg.

The polity ruled by Oleg stretched from Kyiv in the south to Novgorod in the north and the PVL says that “The Varangians, Slavs, and others who accompanied him were called Rusians.”Footnote 54 Thus we see already a concatenation of terms wherein Rusian describes not just the Scandinavians but all those under their rule; a key concept in the Normanist controversy. Rus was made up of numerous groups named in the chronicle, all of whom were required to pay tribute to the ruler. Oleg’s first task after taking Kyiv was raids on the Derevlians, Severians, and Radimichians to subjugate them.Footnote 55 Whether these are really tribal names of the time or were added in later given their formulaic content – the first two names mean forest dwellers and northerners – is unknown. When Igor succeeded to the throne in 913, he had to do the same, re-subjugating those same groups and convincing them to pay tribute to him. Rule was personal and thus ended at the death of the ruler. The new ruler had to create a personal tie of obligation to the subordinate groups. Centralization of political power would not come to Rus until the time of Volodimer Sviatoslavich and was, in many ways, concomitant with the arrival of Christianity.

Oleg and Igor both led raids on Constantinople and both of those raids resulted in treaties interpolated into the PVL. Raids on Constantinople are not surprising given its preeminence in western Eurasia. What might be surprising, however, are the treaties which were created between Rus and the medieval Roman Empire. The treaties read like modern legal documents in which provision is made for equal punishments and responsibility under the law for both “Rusians” and “Christians,” which the treaty uses for the Romans.Footnote 56 The old Rhodian sea law governing wrecked ships is incorporated into the treaties, and there is clear language about slaves, ransoms, theft, and murder. Igor’s treaty, which is overall less advantageous for Rus (presumably because the campaign was less successful) also contains interesting provisions that designated royal agents from Rus required gold seals to identify themselves while merchants had silver seals.Footnote 57 Seals are known from Rus, but the treaty also stipulates that the ruler will include a letter with those seals. The documentary history of Rus is sparse and there are no extant textual sources from this period, nor is there a widespread belief that there was textual evidence from this period.Footnote 58 And yet, the treaty indicates that the ruler would send a letter and seals to prove the validity of his designated representatives and merchants. Given that the Rusian god Perun is written into the treaty, it seems unlikely that this is a stock treaty that would not have been, or could not have been, adjusted for this usage.

The PVL begins not as an annal but by situating Rus within universal Christian history. “After the flood, the sons of Noah divided the earth among them.”Footnote 59 These lines are taken from the chronicle of George Hamartolous but reflect the biblical story of the Flood and the subsequent division of land between Noah’s sons. Japheth’s territory is expanded to include the eastern European territories familiar to the chronicler; specifically, he says, “In the share of Japheth lies Rus.”Footnote 60 It was essential for a new polity to find ways to legitimize itself, especially in regard to integrating itself into Christian history. The grounding of the earliest Rusian chronicle in biblical history is an essential part of that, but it also required placement in not just the Old, but the New Testament. Thus, the chronicler quickly moved forward in time to present a story of St. Andrew. St. Andrew is known to have traveled and taught around the Black Sea, but the PVL takes this several steps farther. Andrew came to the Rusian Sea and noticing the Dnieper he decided to travel upriver to reach Rome. Traveling to Rome by going north along the Dnieper is an unlikely route, adding thousands of miles to his trip, but the point was not speed, but connecting the territory which would become Rus to an apostle of Christ. Andrew stopped along the river at a series of hills and proclaimed that “a great city will arise” there, and subsequently Kyiv was built on that location. But this was not enough, as he traveled to the location of Novgorod to experience a Slavic sauna. Afterward on to Rome to have audiences marvel at his tale, and not to take too long out of his known itinerary. The point of St. Andrew’s journey is one of legitimization and connection. Rus was late to Christianization and was not part of the Roman Empire, but the story of St. Andrew blessing the hills of Kyiv and visiting the saunas of Novgorod, the two poles of the kingdom in the chronicler’s time, endowed Rus with a connection to sanctity.

However, the chronicler also had to service local interests as well as wider ones. Thus, following the account of St. Andrew, he immediately launches into a folk version of the founding of Kyiv wherein three brothers, and one sister, found the city. Kii, the eldest brother was the eponymous founder of the city and the other two brothers’ names grace hills in the city and the sister was Lebed (swan), a river in southern Kyiv which flows into the Dnieper.Footnote 61 The chronicler tells his readers that these siblings were ancestors of many current people in Kyiv, providing a rationale for the inclusion of the tale – glorification of some of the current magnates. Taking foundation stories one step further, the chronicler notes that “some ignorant people believe” that Kii was a ferryman, but that is wrong; instead, he was a powerful ruler who travelled to Constantinople and conquered a wide area. Such a tale seems increasingly far-fetched but may have addressed a persistent rumor at the time about a ferry across the river and Kii’s humble origins. Origins which would not be good enough for those connected to the chronicler writer who had to balance Rusian rulers, local magnates, and Christian history in creating a foundation for Rus.

2 Religion

Excavations carried out in the region of medieval Zvenigorod, between the upper reaches of the Western Bug and San Rivers, have unearthed fascinating objects indicative of the wide reach of pilgrims from western Rus.Footnote 62 An icon of Sts. George and Demetrius made of pewter and from Thessalonica is representative of the traditional understanding of Rusian Christianity. The warrior saints were especially valued in the medieval Roman Empire and in Rus.Footnote 63 In the excavation was also a cross made of wood from the eastern Mediterranean, and numerous seashells (see Figure 2) which have been made into pilgrim’s tokens.

Figure 2 Seashell from Zvenihorod

The seashell is the object given to those making a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia. The shrine of St. James was one of the most important pilgrimage spots in Christendom, but typically it is seen as only of importance to those in Latin Europe. These finds from the twelfth to the thirteenth centuries suggest that this was not the case; instead, Santiago de Compostela had a much larger reach among the Christian faith community. Further evidence of these broad connections is found in a series of pilgrim inscriptions found in the church of St. Gilles in southern France.Footnote 64 The graffiti written in Cyrillic and datable to the thirteenth century include examples such as “God help your servant Semki Ninoslavich.”Footnote 65 Not only is St. Gilles a Benedictine monastery in France, but it is also on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela providing a further connection between Rusian religious travelers and the far west of Christian Europe. Such an image is at odds with the traditional picture of Rusian religion which is solely oriented around the labels “Orthodox” and “Byzantine,” despite much evidence to the contrary. This section will deal with the conversion of Rus and the many religious ties Rus maintained with the wider Christian world to demonstrate their place in Christian Europe and not just an Orthodox oikumene.

Christianization of Rus

It is possible that there was an initial mission to Christianize Rus in the mid-ninth century, as noted in Section 1, however, the widespread conversion of Rus took place in the later tenth century and began with a dyad akin to that of Helena and Constantine.Footnote 66 Olga and her grandson Volodimer are the two who brought Christianity to Rus over the course of approximately thirty years. After the death of Olga’s husband Igor, she ruled as regent for their young son Sviatoslav. During that time, it is well attested that she both took a trip to Constantinople and that she converted to Christianity, though whether or not it was in Constantinople is an open question. The PVL records her trip to Constantinople in the year 955.Footnote 67 Her purpose, according to the Rusian chronicle, was to attain Christian baptism; which she achieved and the patriarch christened her “Helena [Olena – CR], after the ancient empress, mother of the great Constantine.” The emperor, identified as “Constantine, son of Leo” gave her gifts and sent her home as his baptismal daughter. The same chronicle entry records that once she was back in Kyiv, the emperor sent to her and asked for what had been promised to him “presents of slaves, wax, and furs, and soldiers.” Olga demurred and suggested that if the emperor were to come to Kyiv, she would give him those things, but not otherwise. As far as the PVL is concerned then, Olga was baptized in Constantinople at the hands of the patriarch and the emperor, but the story is more complicated. Olga’s visit to Constantinople is recorded in the contemporary Book of Ceremonies. This source was compiled at the order of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos to document the various ceremonies required through examples of actual embassies, receptions, and so forth which occurred during his rule. Olga’s visit is discussed in detail, including with whom she met and who accompanied her, but there is not a single reference to baptism.Footnote 68 Additionally, Olga is referred to as such throughout, rather than by her baptismal name of Helena. This is an oddity in medieval Roman sources which typically use Christian names for people, even those outside of the empire.Footnote 69 Olga’s companions on the journey also raise questions about the purpose of the trip. She was accompanied by a priest, Gregory, who received a monetary gift from the emperor; but it is entirely unclear where he is from, apart from the fact that he was part of Olga’s entourage. While she brought along numerous relations (both male and female) and agents of other Rusian elites, she also brought over forty merchants (forty-three were present at the first reception and forty-four at the second). The presence of such a large number of merchants, twice that listed in the treaty of 944 between Rus and the empire, has given rise to the supposition that the visit to Constantinople was primarily about trade. Finally, two other Greek sources mention this visit John Skylitzes and John Zonaras. Both Skylitzes and Zonaras report that she was baptized in Constantinople, and both also refer to her as Olga (Elga in the sources).Footnote 70 All of which muddies the waters rather than clears them.

It is essential then to look elsewhere for information. The Latin sources also contain information about Olga and her baptism, as well as the Christianization of Rus. That they do is a subtle, but important, statement regarding the place of Rus in Christian Europe. The continuator of Regino of Prum notes in the year 959 that an envoy of “Queen Helena of the Rusians,” who had been baptized in Constantinople, arrived and asked the Ottonian emperor for a bishop and priests to convert her people.Footnote 71 Though brief, this entry adds a great deal to our discussion. Here Olga is referred to by her baptismal name of Helena, the only other source to do so thus far, and her place of baptism is noted as Constantinople, agreeing with the PVL, Skylitzes, and Zonaras. The purpose of the embassy though is of particular note, as she is seeking assistance in conversion from the German Empire. Even basing our understanding solely on Regino’s continuator, it is clear that there was an interesting byplay underway in which the Rusian queen sought baptism from one empire and a bishop from another.Footnote 72 Otto had a bishop ordained for the mission to Rus the next year, but as he died, it was not until 961 that Bishop Adalbert undertook the mission.Footnote 73 “Exhausted” from his toils, Adalbert returned home in 962 unable to report any success in the conversion.Footnote 74 Adalbert’s lack of success can likely be explained by Sviatoslav’s coming of age in Rus. The PVL has him acting on his own as an adult in 964, and it is possible that he was already exercising power before that.Footnote 75 Sviatoslav was himself a confirmed pagan who adopted the habits of steppe dress and accoutrement, and told his mother flatly that he would not convert to Christianity as his “followers will laugh at it.”Footnote 76 Thus, though Olga converted and took the Christian name Helena, Rus as a whole did not convert at this time.

The conversion of Rus to Christianity came about under Olga’s grandson, Volodimer Sviatoslavich, though the process was not without exploration of alternate paths. Volodimer first attempted to create his own pantheon of gods out of the existing deities worshipped by the various peoples within Rus.Footnote 77 But only a few years later, a set of three entries begin in the PVL detailing three different conversion stories, which it seems the chronicler, writing in the late eleventh or early twelfth century, was attempting to put together into a whole. The stories articulate a search for a monotheistic faith from amongst Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, exploring both German and Constantinopolitan variants. Judaism is dismissed largely out of hand after the first story in 986, and the others are investigated more thoroughly.Footnote 78 Though Volodimer does not convert to Islam, there is a substantial presence of Rus in Islamic sources discussing this possibility, something not taken as seriously by the Christian authors of the PVL.Footnote 79 For those authors, the choice comes down to which variant of Christianity? The PVL lauds Constantinopolitan Christianity, spending pages on enlightening Volodimer, and the reader, on the intricacies of faith and the history of church councils, while also describing the interior of Hagia Sophia as heavenly compared to the lack of “glory” found in the German churches.Footnote 80 Despite these pages devoted to the faith, what converts Volodimer is, as might be expected, a miracle, though one connected with dynastic marriage. Under the year 988, Volodimer captured the Roman city of Cherson with the aid of a mole inside the city named Anastasius.Footnote 81 He then offered to give the city back to emperors Basil II and Constantine VIII in exchange for the hand of their sister Anna Porphyrogenita in marriage. The emperors agreed, but stipulated that Volodimer must first be baptized. Anna was delivered to Volodimer in Cherson where, failing to immediately convert, he was struck blind.Footnote 82 Volodimer converted at Anna’s behest, and he was subsequently healed. According to the PVL, the couple returned to Kyiv and Volodimer baptized his population in the Dnieper River Christianizing Rus.

The story beyond the PVL’s telling is, as one might imagine, slightly more complicated. Procopius records that a band of Rusians (Tauroscythians) came to Constantinople in 988 to aid Basil II in putting down uprisings against his rule.Footnote 83 That these troops were sent by Volodimer is confirmed by the Egyptian Melkite Christian, Yaḥya Ibn Sa‘īd (d. c.1066) who recorded that Basil II faced a revolt of one of his nobles and asked for assistance from the Rusian king, to whom he gave his sister in marriage.Footnote 84 Ibn Sa‘īd also notes the baptism of Volodimer and his kingdom, as well, and the building of many churches there. Using these sources, it is possible to expand the story offered to this: Basil II needed troops to assist in putting down the revolt of Bardas Phocas. In exchange for troops, Volodimer asked for Anna Porphyrogenita’s hand in marriage, and despite the fact that she was desired as a prospective bride by both the Ottonian and Capetian royal families, Basil II had no choice but to marry her to the pagan Volodimer. Volodimer sent troops to assist Basil II, but Anna was not forthcoming and thus Volodimer besieged and took the city of Cherson, holding it for ransom until Anna arrived there, at which time the city was returned to Constantinopolitan control (as a “wedding present” according to the PVL).Footnote 85 The pieces fit well in this order and it helps us understand the political rationale for both Volodimer’s and Rusian conversion in order to placate the Roman emperors and Volodimer’s new wife.

The PVL records that “the bishop of Cherson and the priests of the princess (Anna)” were the ones who baptized Volodimer; perhaps tellingly, nothing about the baptism is recorded in Roman sources.Footnote 86 Following his baptism and marriage, he gathered “Anastasius and the priests of Cherson” along with the relics of St. Clement and several bronze statutes and returned to Kyiv. There is no mention in the PVL, nor in Greek sources, of a missionary bishop being sent from Constantinople, though Ibn Sa‘īd does mention that a metropolitan was sent.Footnote 87 The provenance of the relics of St. Clement are an interesting, and still open, question. Constantine / Cyril, on his journey in the Black Sea to attempt the conversion of the Khazars, came upon the relics of St. Clement in the mid-ninth century. He carried those relics with him on his journey and eventually all the way to Rome.Footnote 88 That the relics appeared again in Cherson is odd, unless one gives credence to a later Rusian source which indicates that an embassy was sent to Volodimer from the papacy while he was in Cherson and it bore holy relics.Footnote 89 The relics of St. Clement could play on Volodimer from multiple angles: as a tie to the papacy given Clement’s position as third successor to St. Peter; a connection to the Black Sea where Clement was exiled and the relics were found; a tie to the Apostle to the Slavs himself St. Cyril; and finally, relics of his new religion which had the power to create miracles. Whatever their origin, they became prominent relics in Rus and, according to Thietmar of Merseburg, Volodimer erected a church in Kyiv for them and this was where he and Anna were buried.Footnote 90 This church is not recorded in the PVL which suggests that the first church he built in the city was dedicated to his patron St. Basil and the next year he built the Tithe Church in Kyiv which he entrusted to Anastasius of Cherson.Footnote 91 Volodimer also “appointed priests from Cherson” to the church and gave it the appropriated goods from that city, perhaps including the relics of St. Clement. Anastasius is known only as the betrayer of Cherson in the PVL, and yet he is here appointed to one of the first churches in Rus with a staff of priests from Cherson. There is no evidence in the PVL that there was a Constantinopolitan metropolitan directing affairs, rather Volodimer himself was the agent behind such appointments; and later the royal family itself was responsible for founding churches and appointing priests, as was common throughout medieval Europe.

The first mention of a metropolitan in Rus is when Metropolitan Theopemptos consecrated a new church in 1039.Footnote 92 There is no recorded metropolitan before this time, though much debate exists on this topic. The record of metropolitans is incomplete with multiple gaps of years with no mention of anyone serving in that office, especially in the eleventh century. The majority of metropolitans were appointed to Kyiv by the patriarch of Constantinople. It is widely assumed that they were unable to speak the local language and, in fact, little is known of any of their life and career before their appointments until the middle of the twelfth century.Footnote 93 In the mid-eleventh century, late in his tenure as ruler, Iaroslav Volodimerich created the first native Rusian metropolitan, Ilarion.Footnote 94 The language of the PVL is quite interesting as it says that “Iaroslav, after assembling the bishops, appointed Ilarion as metropolitan in Holy Sophia [the metropolitan church in Kyiv].” This is the entirety of the information provided in the chronicle about his appointment and thus it seems that it was Iaroslav himself who did the appointing and thus the episode has been connected with the 1043 Rusian attack on Constantinople and a disjunction in relations.Footnote 95 Ilarion does not seem to have been metropolitan long, but he is well-known for his “Sermon on Law and Grace” which integrates Rus into biblical history.Footnote 96 After Iaroslav’s death, Rus enters a period in which it has three metropolitans for a period of time, and it is unknown which of them, if any, were appointed from Constantinople. In 1055, the Novgorod First Chronicle records the presence of a Metropolitan Ephraim.Footnote 97 An Ephraim appears later as a Rusian monk, and eunuch, who traveled to Constantinople to experience monastic life there, and was the source of the Stoudite Rule in Rus.Footnote 98 He then became metropolitan of Pereiaslavl while there were also metropolitans for both Kyiv and Chernigov in the 1070s and 1080s. Attempting to make sense of this troika of metropolitans has bedeviled historians for generations, resulting in numerous theories.Footnote 99 The See of Rhosia was the single largest metropolitanate subordinate to the patriarch of Constantinople, and yet the patriarchs were unwilling to divide it, as is seen several times in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries.Footnote 100 The PVL records a Metropolitan Georgios in 1073 only by noting that he was absent in the Roman Empire at that time, and then the next mention of a metropolitan is Ioann in 1086.Footnote 101 The entry for 1089 encapsulates part of the problem with who was metropolitan and when as it notes that Metropolitan Ioann died; that Ianka Vsevolodovna was sent to Constantinople for a new metropolitan (also named Ioann), and that “Ephraim, the metropolitan of that church” consecrated “the Church of St. Michael in Pereiaslavl.”Footnote 102 The entry continues with a listing of the ecclesiastical deeds of Ephraim in that region. But then, in 1091, Ephraim is listed under a series of “bishops” and in the Paterik of the Kyivan Caves Monastery he is only listed as a bishop.Footnote 103 Affairs become slightly more regular and better documented in the twelfth century, for instance we know a good deal about the career of Metropolitan Constantine II in the 1160s as he disciplined the monks of the Caves Monastery and mutilated Bishop Feodor of Suzdal.Footnote 104

The role of the metropolitan of Kyiv as the leader of the Church and delegate of the patriarch of Constantinople leaves more questions than answers when the source base is examined. It is widely accepted by scholars that the PVL was written by monks who were part of a Church hierarchy which reported to a metropolitan of Kyiv.Footnote 105 Despite that belief, the chronicle record is surprisingly uninterested in the affairs of the metropolitans. Combined with the lack of updates to the menologia with the names of patriarchs post-ninth century, it is possible to suggest that the ecclesiastical relationship between Rus and Constantinople was not nearly as strong in the eleventh to twelfth centuries as is widely imagined.Footnote 106

Gertrude’s Psalter

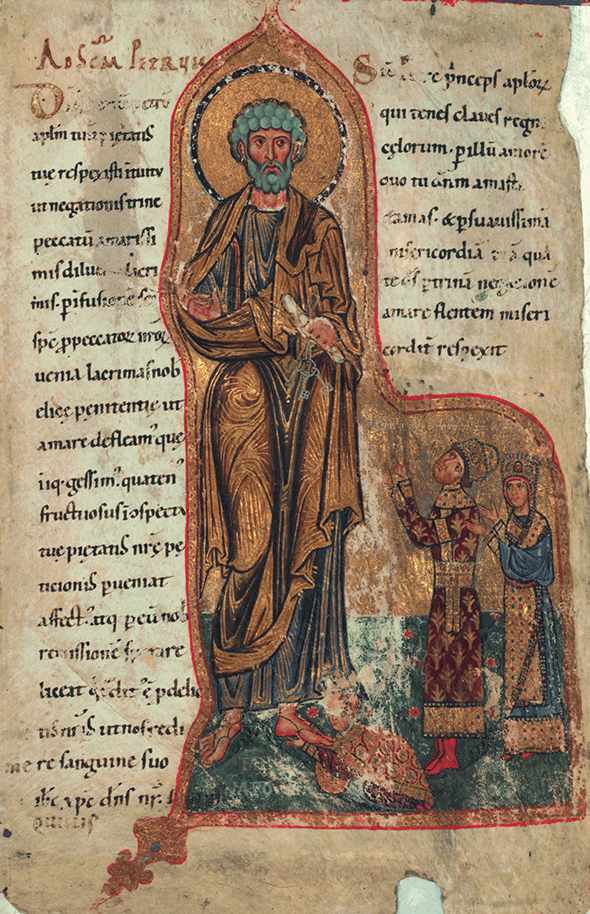

One of the most well-known women of medieval Rus is Gertrude, the Polish princess who became the wife of Iziaslav Iaroslavich in the middle of the eleventh century. Gertrude appears in almost no textual sources by name, and yet she left behind a marvelous testament to her existence and her faith. The Gertrude Psalter, also referred to as the Egbert or Trier Psalter, began life in the Ottonian Empire in the tenth century and came into Gertrude’s possession via her mother, Richeza, a member of the Ottonian family.Footnote 107 In Rus, Gertrude added a number of prayers to the codex as well as several images.Footnote 108 For all of these, she was the maker, to use Therese Martin’s evocative term which points out the “false dichotomy” in modern scholarship between artist and patron (which itself is gendered male); instead noting that medieval inscriptions used “made” (fecit) for those who physically constructed something as well as for those who paid for said construction.Footnote 109 Gertrude’s Psalter, the pieces composed in Rus and made by her, then are statements of her faith.

Gertrude was a devout Christian with a particular devotion to St. Peter, which may have been because of her son Iaropolk’s visit to the papacy in the early 1070s, or because that was his Christian name.Footnote 110 One of the images in the Psalter is of St. Peter (Figure 3).

Figure 3 St. Peter Gertrude Codex – Cividale del Friuli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Archivi e Biblioteca, codex CXXXVI)

Gertrude herself appears in this image, one of only a few examples of an image of a medieval Rusian woman we can identify. She is not named, however. The label above her head reads simply “Mother of Iaropolk.” “Mother” is a ligature and could be Greek, but “Iaropolk” is written clearly in Slavonic. Gertrude herself is performing proskynesis, the traditional donor, ktetor, pose at the base of St. Peter, clasping his foot. Given all that we understand about medieval art composition, she is identified here as the maker of this work. The work itself is exceptional and simply examining this one page will highlight Gertrude’s religious experience which crosses what moderns have divided into separate faith traditions.

Gertrude came from the “Latin” world as a Polish princess and the psalter itself has its origins in the German Empire. It is no surprise then that the text of the psalter, even the 95 prayers added in Rus, are in Latin. The prayers on this page are clearly made with the shape of the illumination in mind as they conform to the space provided on St. Peter’s right and left. The prayer to his left (the right of the page) has been seen as Gertrude’s direct address to St. Peter:

O Saint Peter, prince of the Apostles, who holds the keys of the kingdom of heaven; through that love by which You loved and love the Lord, and through His sweetest mercy by which God mercifully looked down on you as you wept bitterly over your triple denial, mercifully look upon me the unworthy handmaiden of Christ; absolve the bonds of all my vices and crimes.Footnote 111

Gertrude herself is the “unworthy handmaiden of Christ” and thus along with her image as donor, she appears twice on this page of the psalter. Talia Zajac has pointed out the Latin elements in this prayer such as the “keys of the kingdom of heaven.” While there were some instances of the presence of keys related to St. Peter in medieval Roman iconography, it was largely confined to the western tradition as a way to recognize St. Peter as the first pope. In the image of St. Peter on the page one can also see the keys in his left hand, along with a scroll, reinforcing the textual description of the keys.

A connection with the papacy may also be made here via the presence of Iaropolk and his wife Cunigunda, the two figures at St. Peter’s left receiving his blessing. In 1073, Iziaslav was expelled as the ruler of Rus and taking Gertrude and their son Iaropolk, fled first to Poland and then to the German Empire. While Iziaslav appealed for help to Henry IV at Mainz, Iaropolk, and his new German bride Cunigunda, were sent to Rome to meet with Pope Gregory VII. The pope listened to Iaropolk’s plea and granted the kingdom of Rus to Iziaslav, via Iaropolk, in exchange for fidelity to the papacy.Footnote 112 Pope Gregory VII then sent a papal legate with the Rusian family to deliver a message, and possibly a crown, to Bolesław II of Poland who subsequently assisted Iziaslav to return home and regain rule in Rus.Footnote 113 At Iaropolk’s death in 1086, the Rusian chronicler records that he had built a church dedicated to St. Peter, the first of its kind in Rus.Footnote 114 Numerous scholars have discussed the possibility of a conversion of Iaropolk to Latin Christianity or possible dedication to the papacy, but it is important to clarify that conversion was not required at this time and in fact what is seen here is evidence of the “big tent” of Christian Europe.Footnote 115

Gertrude’s psalter as a whole provides additional evidence of this “big tent” or perhaps simply the lack of the hard dividing lines which we imagine existed in the medieval past. The image of St. Peter in Figure 3 is largely medieval Roman in composition. A contemporary medallion made in Constantinople shows the same bust image of St. Peter with eyes shifting to the viewer’s right.Footnote 116 The medallion is clearly labeled “o agios Petros” on either side of the saint’s head, something which is present, but difficult to see in the psalter page. The Latin prayers of Gertrude are original (to the saint’s left) and a borrowing from an Anglo-Saxon prayer (to the saint’s right).Footnote 117 And thus, the image is representative of Gertrude’s life and wider faith tradition in Rus: Latin, Greek, and Slavonic text on one page. Medieval Roman design elements mixed with those from the Latin West. All combined into one whole.

Though Gertrude has been given, and deserves, immense credit for the psalter; the Christian life of Rus was not strictly oriented toward the Roman Empire or away from the West, in general. One place where this is abundantly clear is in the celebration of saints’ days in Rus. Over time, certain saints worshipped throughout the Christian world began to be celebrated on different days in different places. In Rus, we see a mix of medieval Roman and Latin days in the menologia. The earliest Rusian menologion is the Ostromir Gospel, created for the eponymous mayor of Novgorod in 1056/1057.Footnote 118 It contains several saints’ days which accord with the Latin calendar rather than that of Constantinople, including Silvester, Polikarp, and Vitus.Footnote 119 The second oldest menologion is contained in the Archangel Gospel of 1092.Footnote 120 This, too, contains divergent dates for saints, but different saints than had appeared with Western dates in the Ostromir Gospel. The Archangel Gospel lists Latin dates for the Apostle Paul, the martyrs Kosmas and Damian and several others.Footnote 121 In addition, it contains a listing for St. Wenceslaus who does not appear in Constantinopolitan menologia.Footnote 122 Dated to the third quarter of the eleventh century is a birchbark document from Novgorod which contains a list of saints and saints’ days, though all are in keeping with the Constantinopolitan calendar.Footnote 123 Finally, coming back to the Gertrude Psalter, it contains the same feast days as the Ostromir Gospel, perhaps suggesting a common origin.Footnote 124 One thing that the Rusian menologia have in common is that they do not contain sainted patriarchs after Nikifor who died in 828.Footnote 125 A glaring omission given the modern understanding of the relationship between the churches.

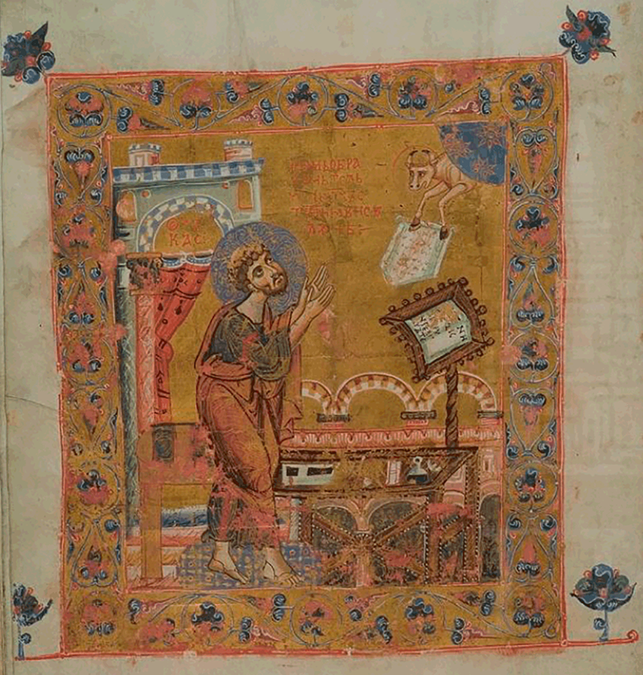

Rusian religious books also give us another glimpse into an appropriation of Western design, the symbols of the evangelists. Drawing on the Book of Revelation, early Church Fathers created symbols for each of the gospel writers. The most commonly used set in medieval Europe was that created by St. Jerome comprising: the Lion for Saint Mark, Angel for Saint Matthew, the Eagle for Saint John, and the Ox for Saint Luke. Typically, medieval Roman illuminated manuscripts do not include the symbols for the evangelists.Footnote 126 When symbols for the evangelists do appear, they do not often follow the Hieronymic model. Instead, there are other pairings of evangelist and symbol, such as that of Epiphanios: Matthew – Man; Mark – Calf; Luke – Lion; John – Eagle.Footnote 127 This format can also be seen in the Georgian Gelati Gospels which were composed on Mt. Athos during the late Komnenian period.Footnote 128 Rusian manuscripts of the eleventh to twelfth centuries, however, both depict the evangelists with symbols and they regularly, and only, use the Hieronymic system. The Ostromir Gospel has images of the three of the evangelists preserved, Mark, John, and Luke.Footnote 129 The image of Luke can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Miniature of St. Luke from the Ostromir Lectionary

The portrayal of Luke has many similarities to that of St. Peter in the Gertrude Psalter; in terms of the chrysographia and bright colors evocative of the cloisonne enamel which was so prized by the Rusians. What stands out, however, is the ox appearing in the upper right-hand corner, handing the parchment to St. Luke; the ox being the Hieronymic symbol for St. Luke. The same can be seen in the illumination of St. Luke from the twelfth-century Mstislav Lectionary (Figure 5).Footnote 130

Figure 5 Miniature of St. Luke from the Mstislav Lectionary

Though the artistic style has altered slightly, all of the stylistic elements have been retained, inclusive of the ox handing St. Luke the unrolled scroll. Returning full circle to the Gertrude Psalter, we can see the symbols of the evangelists there as well (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Miniature of Christ enthroned, folio 10v

In the image of Christ Enthroned (Figure 6), he has above him all four of the symbols of the evangelists; perhaps with a stylistic pairing of the tetramorphs below him as well. The Gertrude Psalter is well known as an object which is representative of a Latin woman bearing her religious identity in Rus. But the Ostromir Gospel and the other texts examined in this section have no such personal connection to a Latin figure, male or female; and yet, they too bear the hallmarks of coming from an ecumenical Christian environment not dependent upon Constantinople. What we might then suggest is that the Rusian Christian world was a syncretic one where Christian elements came from the medieval Roman Empire, but also from Poland, Hungary, the German Empire, Anglo-Saxon England and elsewhere along with the many visitors, traders, and spouses to Rus.

In the early twelfth century, a Rusian monk named Daniil traveled to Jerusalem on pilgrimage. He left a record of his journey which describes distances traveled, churches and wonders seen, as well as his reception in the city itself. At this time, Jerusalem had been taken by the First Crusade, which received no mention in the Rusian chronicle record.Footnote 131 Baldwin was king and given the timing of the pilgrimage in 1107-1108 it is likely that this was during the interregnum before Ghibellin of Arles became patriarch in 1108. Baldwin welcomed Daniil to Jerusalem and took him to pray at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.Footnote 132 Daniil refers to Baldwin as “my ruler [kniaz’] and my lord” when thanking him for his graciousness. Daniil then processes into the church with Baldwin and the abbot of St. Sabas monastery where he watches the service. Daniil designates the priests at the high altar as “Latin” and notes that they began “to squeal” their prayers, as opposed to those of the correct faith (“pravovernii”) who sang Vespers. This is the only derogatory mention of the Latins in Daniil’s text, and one can surmise that it has as much to do with the sound of the Latin chant as anything else. Unfamiliar sounds have often been described in such ways, witness the Greek label for barbarians – those who make a ba-ba sound, or the Slavs label for Germans – nemtsy – those who cannot speak. Daniil records that Baldwin, whom he addresses with the same title (kniaz’) as he does Rusian rulers, allows him to record the names of the rulers who sent him and points out that all that happened can be affirmed by the other Rusians on the journey, several of whom he names. Daniil’s visit is indicative of the broad Christian ecumenism present in Rusian belief that differs from the invective recorded in some texts, including the PVL during Volodimer’s conversion.Footnote 133 There is little idea in Daniil’s text of tension between the various Christianities nor hostility about a Latin patriarch.

The crusades in the eastern Mediterranean were of little interest, at least according to preserved writings, to the Rusians. The sack of Constantinople in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade is recorded in some detail by the Novgorod Chronicle, though the account is focused upon, and bookended by, the struggle between Roman contenders for the throne.Footnote 134 There is no religious animus against Latins or for Orthodox. The sacking of churches is mentioned and condemned, simply because they are churches. For the lived experience of the people of Rus, the separation from the Latin world really occurs with the activities of the papal legate, William of Sabina. In 1222, Pope Honorius III declared that Orthodox churches should be closed in all Latin lands. This was not a problem in most places, as there were few in the majority of Western Europe. However, in the Baltic, both Christianities had coexisted for some time, as is seen by the presence of Latin churches to St. Olaf in Novgorod, and Rusian churches on Gotland.Footnote 135 The impact of Pope Honorius’ edict came with the Latin conquest of Dorpat in 1224. Dorpat had strong ties with Novgorod and there were Orthodox churches within its borders, all of which were closed. William of Sabina also ordered proselytization of the Orthodox population. The combination of these factors led to a disruption in the Novgorodian lands and Iaroslav Vsevolodich, ruler of Novgorod, attacked Dorpat in 1234.Footnote 136 Legate William responded by agitating the papacy for a crusade directed against Rus, which Pope Gregory IX granted in 1240. A clear rift between Latin and Orthodox had been created, and yet even after that time, there were still some who managed to exist between those worlds, trading and working for both parties.Footnote 137

3 The Kingdom of Rus: From the Inside

The idea of Rus as a kingdom, as an organized polity even, is rare in the secondary scholarship. An essential element in a series focused on “Rethinking” polities is attempting to understand and articulate how Rus functioned as a kingdom and how it was governed. This section divides the issue into two; first dealing with the existence of a “kingdom” of Rus, and the title of the Rusian ruler; second is a brief look at what governance looked like in Rus via the various positions which made up the court and the functionaries in the kingdom.

Titles – From Prince to King

In the early thirteenth century, Henry of Livonia wrote about the ongoing conflict in the Baltic between the local Livs, the Rusians on the other side of Lake Chud (Peipus), and the newly arrived Germans and their crusaders. Rus is interwoven into Henry’s narrative as the various Rusian rulers played a major role in Baltic affairs. Henry says, “the great king of Novgorod, and likewise the king of Polotsk, came with their Russians in a great army … ”Footnote 138 “King Vladimir went with these Letts … ”Footnote 139 and later “the Russians kings … ”Footnote 140 Throughout his chronicle, Henry refers to the rulers of Rus as kings, using “rex” or “reges.”Footnote 141 James Brundage who has translated the chronicle into English, uses “king” in his translation, but then adds a footnoted caveat early in the text: “Vladimir was a Russian prince, not a king, as Henry calls him.”Footnote 142 And slightly later “Like the ‘king’ of Polozk, the ‘king’ of Gerzika was a Russian prince.”Footnote 143 Brundage was a historian of medieval canon law and entered crusade studies from that angle. To help him with unfamiliar territories and peoples, like all good scholars, he turned to existing scholarship and definitions. Though Brundage first published his translation in 1961, the Columbia UP edition is from 2003 and he could have used Simon Franklin and Jonathan Shepard’s The Emergence of Rus for the revised notes, as they use “prince” as the title for the Rusian rulers throughout. So does Janet Martin’s Medieval Russia, at least when speaking of the Kyivan period.Footnote 144 Even if Brundage would have turned to an expert on Russian history, for that is the designation both in the book and which is largely common still in the field, he would have found that a simple translation of the word “kniaz’” into English is “prince.”Footnote 145 However, I would suggest, and have,Footnote 146 that the medieval Rusian ruler’s title should be translated as “king,” as Henry of Livonia originally used. So, why is this not reflected in the scholarship or in translations?

As is often the case, there are several reasons for why kniaz’ is translated as prince. One is due to the vagaries of the denotation and connotation of “king.” Another is historical practice. Those two will be dealt with sequentially here. The first issue does not have anything specific to do with the word kniaz’, or really the word prince, but primarily with the word “king.” The third of the Henry of Livonia quotations above, regarding “Russian kings” illustrates the problem well. There were many people in Rus who bore the title king. Henry did not have a problem with this. Similarly, Abbot Wilhelm, writing around the same time as Henry of Livonia, noted that Queen Sophia of Denmark was born to the “king of the Rusians, for they have many kings there.”Footnote 147 Wilhelm, like Henry, does not include a statement of judgment when he notes the multiple kings, he is simply sharing information and wants to clarify for his audience. For modern peoples, though, multiple kings is an oxymoron. King equals monarch, and monarch is, literally, a sole ruler, thus there can be only one.Footnote 148 The idea that in Rus there were multiple kings then immediately disqualifies the ruler from having the title of king, despite the fact that this was the title which they were given in multiple Latin sources (rex) and Scandinavian sources (konungr); and even despite the shared etymology of kniaz’ with konungr and even with king. It is much more common in modern medieval history writing to give the title of king to a sole ruler, such as a king of England. Even when said sole ruler, also had other kings subordinate to him whether that be Alfred the Great or Henry II. There, historians are willing to make an exception due to the early Middle Ages, or to anticipatory association.Footnote 149 The mindset which, I would suggest, developed as part of the Enlightenment has situated within moderns a hierarchical worldview and a need for structure, especially in government, that was absent for much of the middle ages. Another place to see this same phenomenon is in coins. Medieval numismatics is a robust field, and coin collections have been carefully curated at universities and institutions such as Dumbarton Oaks. To take just one figure, the mid-eleventh-century Eudokia Makrembolitsa as an example, we can see her on multiple coins in the DO collection. She appears with her husband, Romanus IV Diogenes on a coin during their rule and yet the coin is labeled simply as “Nomisma tetarteron of Romanos IV Diogenes (1068-1071)” with no mention of Eudokia (Figure 7).Footnote 150

Figure 7 Nomisma tetarteron of Romanos IV Diogenes (1068-1071)

Eudokia’s presence was essential for Romanos IV because it was via her authority as the widow of Constantine X and regent for their sons, that he was allowed to claim royal authority at all. The complexity of the situation can be clearly seen on other coins and seals wherein Eudokia and her sons with Constantine X appear with Romanos IV regularly.Footnote 151 The DO collection does include Eudokia in its catalog, “Nomisma histamenon of Eudokia Makrembolitissa (1067)” (Figure 8).Footnote 152

Figure 8 Nomisma histamenon of Eudokia Makrembolitissa (1067)

Yet, this coin does not simply depict Eudokia, but her children with Constantine X as well. Eudokia may have been ruling, but her rule was inextricable from that of her children for whom she acted as regent. It was on their behalf that she married Romanos IV to provide a protector for their legacy, even while he was accused of acting against them. The corulership on both of these coins was done on purpose to demonstrate visually to the people of the Roman Empire who their rulers were. The images included connectivity with the past ruler via Eudokia and via her sons, connections which were essential for claims of current power. But for moderns this level of complication does not easily fit into our hierarchical categorization of rule. The Roman Empire is ruled by an emperor; singular. Thus, we need to be able to choose an emperor to occupy that position, from the many given to us by our source materials.

All of which is highly relevant to the situation in regard to Rus. Multiple rulers with the same title at the same time created the idea that there was no political centralization and hierarchy with a king at the top of a pyramid. Thus, there could be no king and the translation for the rulers of Rus needed to be something of which there could be many, prince or duke (the latter more common before the twentieth century) fit the bill nicely. It is worth emphasizing that the issue in regard to a plurality of rulers is not centered on Rus, but on our modern perceptions of rule and corulership. By exploring what we think we know, perhaps we can gain a better understanding of the ways that medieval peoples approached their own rulership.Footnote 153

The multiplicity of rulers with the same title was one problem, but there is also the problem of historical translation which needs discussion. Rus was connected into the medieval European world and its rulers appear in Latin, Old Norse, and Greek sources. But it was not until the early modern period that English travelers, writing in English, reached the area and began writing about the polities which they found there. Queen Elizabeth of England had ties with the court of Ivan IV of Moscow and his son Feodor. One of her most famous ambassadors was Giles Fletcher who traveled to Muscovy in 1588 and wrote about the experience a few years later in a work entitled “Of the Russe Commonwealth: or, Maner of Governement by the Russe emperour (commonly called the Emperour of Moskovia) with the manners and fashions of the people of that Countrey.”Footnote 154 The full title, in properly elaborate Elizabethan form, denotes the subject and is important for why Fletcher is used here. Fletcher approached Muscovy as an empire, with an emperor. When he wrote about the nobility, who served under the emperor, he categorized them as he saw them in the late sixteenth century, but also through the inevitable lens of his own experience. Thus, he says, “The degrees of persons or estates of Russia (besides the soveraigne state or emperor himselfe), are these in their order.”Footnote 155 The first and fourth are the most important orders for our purposes, and Fletcher’s text will be quoted here at length:

The nobility, which is of four sortes. Whereof the chiefs for birth, authoritie, and revenue are called the udelney knazey, that is, the exempted or priviledged dukes … The fourth and lowest degree of nobilitie with them is of such as beare the name of knazey or dukes, but come of the younger brothers of those chiefe houses, through many descents, and have no inheritance of their owne, save the bare name or title of duke onely.Footnote 156