1 Introduction

Wer fremde Sprachen nicht kennt, weiß nichts von seiner eigenen. People who know no foreign languages know nothing of their own. This has been replaced by a third global English myth, namely that in international communication the only language you need is English, as expressed in my update of Goethe’s maxim: Wer Englisch kennt, braucht keine anderen Sprachen. Whoever knows English has no need of other languages.

1.1 Scope of the Element

This Element addresses the challenges Global English poses to the formal (school) learning of languages other than English (LOTE). As Global English is continuing to change our language learning landscape, policymakers, educators and learners themselves need to adapt to the sometimes unpalatable reality that one language seems, to many learners, more desirable to learn than any other (Reference de Swaande Swaan, 2001a). Globally, many language education systems continue to be marked by English displacing other languages hitherto used (Englishisation), while targets for LOTE learning are not achieved. Mass migration and increasing societal multilingualism in a wide range of LOTE further add to an increasing mismatch between official language education policy (LEP) and sociopolitical needs for language skills. Language education policy planning and school provision remain ill equipped to respond to the challenging needs for a twenty-first century education (Reference KramschKramsch, 2014; Reference PachlerPachler, 2002).

While international organisations subscribe to equality of all languages (Council of Europe, 2020; UNESCO, n.d.), the Englishisation of education systems continues (e.g. Reference Wilkinson and GabriëlsWilkinson & Gabriëls, 2021a). Recently, the discipline of applied linguistics has undergone radical paradigm shifts advocating equality in language learning and language use, most importantly the multilingual turn (Reference MayMay, 2019) and the translanguaging turn (Reference García, Wei, García and WeiGarcía & Wei, 2014). Meanwhile, the undeniable preference for the learning of English over LOTE has received comparatively less attention (Reference Lanvers, Thompson and EastLanvers et al., 2021a). Thus, as modern paradigms in applied linguistics strive for ever more equity between languages, and in language use, breaking disciplinary and language boundaries (Reference WeiWei, 2020), language learning preferences and uptake patterns remain unaffected. We observe a growing gap between the conceptual developments in applied linguistics and language policy on the one hand, and practices of language learning on the other (Reference Gazzola, Gobbo, Johnson and Leoni de LeónGazzola, 2023).

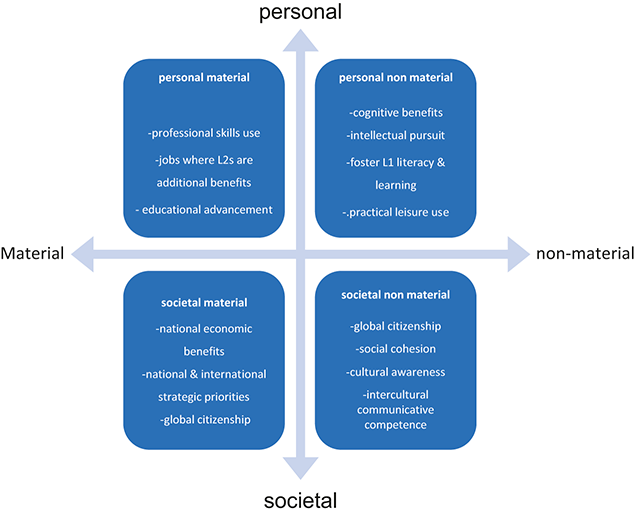

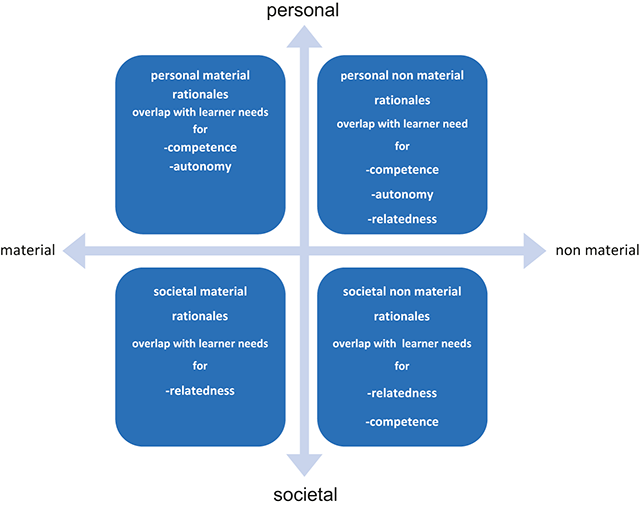

This Element addresses these widening gaps in a two-pronged approach. First, it revisits traditional rationales for language learning, reframing them in a new scheme that emphasises non-material justifications for language study more than past rationales. This holistic matrix of rationales is designed to support educators and policymakers in designing and formulating their own language policy in the most comprehensive manner possible. In a novel departure, the matrix of rationales proposed here consists of two continuum dimensions:

Who benefits from language learning (individual or society)?

What is the nature of the benefit (material or non-material)?

The Element then undertakes the exacting task of connecting such rationales to our – by now, considerable – knowledge about language learner motivation. Although the twenty-first century has seen some conceptual contributions on the topic of rationales for language learning, it remains somewhat under-theorised. Rationales have also rarely, if at all, been linked to learner motivation, a striking lacuna since official rationales for LEP might be utilised to help learners understand the relevance of their endeavour. The second argument of the Element is that rationales can indeed be used to help motivate learners, provided that two conditions are met: they are explicitly communicated to, and discussed with, learners, and rationales are tailored to the basic human motivational needs of learners engaged in language study.

By preference, official rationales for language learning should help motivate learners. Despite a prolific literature on language learner motivation, the relation between rationales and motivation has hardly been investigated. The reason for this lacuna is that they operate at different levels: while rationales are logically conceptualised by policymakers, motivation sits (largely) at the experiential level of the individual. The best rationale for language learning could not compensate for a learner’s experience of boredom in the classroom. Nonetheless, rational arguments for language learning have been used as motivational incentivisation in intervention studies. The online supplement to this Element (available at www.cambridge.org/lanvers) offers practical activities and methods designed to incentivise non-material motivation for language learning. In this sense, this Element bridges LEP research, language learning motivation research and pedagogical practice.

This Introduction sets out the incentive and context of the Element. Beyond, the Element is structured as follows: Section 2 asks under what conditions English might be framed as a threat to learning LOTE. Three conceptualisations of global language systems are discussed, and each system is scrutinised for the light it can shed on the question of what rationales might remain for the study of LOTE. The section concludes that, irrespective of whether English dominance in language learning is considered desirable, inevitable or harmful, language learning and teaching models conceptualising different language skills and their purposes as discrete neglect important recent paradigm shifts in applied linguistics, namely the multilingual turn and the translanguaging turn in language learning.

Section 3 first discusses the existing literature on rationales for formal language education and then presents a novel, two-dimensional matrix model of rationales for teaching foreign languages. This matrix, it is argued, can help policymakers, educators and learners themselves in reflecting on and formulating their specific motivation for language study, adapted to their contexts. Rationales for any formal language study have, hitherto, been under-theorised and often perform justificatory functions, defending policy rather than serving as a nexus from which curricula, schemes of work, pedagogies and so forth may emerge. The holistic matrix provided here is designed to help policymakers to formulate their rationales in the most holistic way possible for their context, and to communicate these better to stakeholders.

Section 4 undertakes the delicate translation from rationales to motivations. Putting rationales into the service of motivating learners is subject to many caveats, as many motivational factors, such as liking the teacher, lie outside the conceptual and logical remit of rationales. Nonetheless, some rationales overlap with motivational dimensions, and forms of incentivisation relating to this nexus remain underutilised to date. There is evidence that if rational incentivisation is targeted to specific learner groups and their specific motivational needs, it can have positive motivational effects. In other words, Section 4 puts the matrix into the service of motivating learners. Section 5 pulls together these different strings and discusses how we might best protect the learning of a diversity of languages in the future.

1.2 A Personal Professional Trajectory

If the world ‘stampedes’ towards the one language with the highest prestige while neglecting others, it might suggest that many learners share a somewhat asymmetrical motivational orientation, one that lacks appreciation of non-material, especially personal non-material rationales and benefits of language learning. The by now considerable wealth of empirical studies on language learner motivation underscores this observation. This global challenge in language learning has directed my attention towards rationales, questioning more closely why we make students learn foreign languages. Too often, in my experience as a secondary school language teacher in the UK, the legitimate student question But why should we learn this? has remained poorly addressed, if at all. The language learning crisis, triggered by Global English, has incentivised me to rethink rationales for language study more thoroughly, but the fundamental claims of (1) conceptualising all rationales holistically, with equal validity, and (2) connecting rationales to motivation reach far beyond this problem.

This Element also provides a reflection on the stages of my own involvement in language learning: from a somewhat ‘rebellious’ learner, preferring French to English as foreign language, to a teacher struggling with low student motivation, to a researcher focusing on student motivation, to a researcher focusing on education policies and global language trends, in order to finally realise the interconnectedness of these. Thus, to the extent that this Element interweaves empirical research with my personal trajectory, it is empirically grounded, but such ‘joining of the dots’ has also led me to a conceptual contribution concerning the nature of rationales for language learning, and the connectedness between rationales and motivation.

1.3 What Is Language Education Policy?

A traditional critical sociolinguistic approach to LEP views policy as ‘one mechanism by which dominant groups establish hegemony in language use’ (Reference TollefsonTollefson, 1991: 16), thus enabling dominant groups to shape language practices in alignment with their ideology (Reference ShohamyShohamy, 2016). This conceptualisation of LEP stresses the hegemonic power dynamics of institutions shaping participant behaviours. In this view, (lack of) equity in LEP might be gauged by the extent key stakeholders are involved in policymaking (Reference TollefsonTollefson, 1991: 211). Language education policy can be officially declared in ratified documents and practised at the level of educational institutions and the individual, as well as debated and contested. Language education policies are always created in their politico-ideological contexts (Reference KramschKramsch, 2005). Different metaphors have been applied to describe the multilayeredness of LEP, the best known being Reference Ricento and HornbergerRicento and Hornerger’s (1996) onion metaphor; other descriptors include top-down versus bottom-up, implicit versus explicit, de jure versus de facto.

More recent theoretical contributions to language policy stress how policy is enacted, co-created and negotiated at all levels: the macro, meso and micro-levels (Reference Gazzola, Gobbo, Johnson and Leoni de LeónGazzola et al., 2023). This Element adopts the latter view of LEP, as constantly shaped in a dynamic interaction of bottom-up and top-down forces. However prescriptive and regulatory policies might be in their inception, they are interpreted, shaped and altered by those acting out LEP (Reference Johnson and JohnsonJohnson & Johnson, 2015). Stakeholders such as learners, parents and the public contribute to and co-construct policy daily (Reference SpolskySpolsky, 2019). A nation-state passing policies on language education is a top-down, declared, deliberate, visible discourse of LEP, created by politically dominant groups. A particular teacher debating with their class why they might want to study a language, or using their preferred teaching method, sits at the opposite end of the policy continuum. Enacted policy is largely invisible, but has great impact on LEP in practice, at the micro- and even meso-level. Both are embedded in their sociopolitical context, but their exposure to political ideology differs widely: at the macro-level, policymaking is subject to greater politicisation, by virtue of the combination of greater scrutiny, accountability and the need for ideological alignment with other, more general policy directives.

In this view of LEP, all actors involved in LEP are also engaged in formulating, debating and reshaping rationales for learning and creating (in)felicitous conditions for positive learner motivation. For these reasons, discourses on language learning are integral to LEP, not separate from it. Ideologisations of policies are expressed in texts describing and debating policies.

1.4 Policy–Practice Gaps in Language Education Policies

This section offers empirical underpinning for the argument that education systems, globally, experience Englishisation in the form of increased learning of English as a foreign language. It is not hard to find examples of LEP not reaching its targets due to English dominance, in both anglophone (Reference CollenCollen, 2020; Reference Lanvers, Thompson and EastLanvers et al., 2021a) and non-anglophone (Reference Wilkinson and GabriëlsWilkinson & Gabriëls, 2021a) contexts. To some extent, discrepancies between declared and practised LEP are inevitable: in the complex process of implementing LEP, intentions and rationales get interpreted, (mis)construed, diluted and distorted, as local agents of LEP apply their own resources, limitations, preferences, attitudes and ideologies (Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2013). Such discrepancies are most apparent when language education is obligatory: declared targets can be measured against actual uptake. Degrees of discrepancy are, however, also indicative of conflicts between different stakeholders involved in language learning: they reveal underlying tensions between those in power to declare LEP, and those enacting it (Reference Johnson and JohnsonJohnson & Johnson, 2015).

1.4.1 Method and Structure

In this section, global language learning trends in formal school education are presented by region (anglophone/non-anglophone). Such a broad macro view necessitates a methodologically concise remit. In both anglophone and non-anglophone contexts, patterns are presented by large geographical areas. Official uptake figures of the last three decades on formal school foreign language (FL) uptake at upper secondary level are reported (where available), ordered by geographical area and, within this, largest data set available (e.g. the European Union rather than their member states). For both anglophone and non-anglophone contexts, attitudinal and contextual challenges for LOTE learning are also discussed. The literature and data searches reveal, as so often in applied linguistics, a strong Global North bias in the literature and data available (Reference Pennycook and KirpatrickPennycook, 2020): precise data from many areas in the Global South remain less accessible than from the Global North.

1.4.2 Language Learning in Anglophone Contexts

1.4.2.1 Uptake Trends

Today, the term ‘crisis’ can be found frequently when describing language learning in many anglophone countries, such as the UK (Reference BowlerBowler, 2020), the US (Reference BermanBerman, 2011; Reference WileyWiley, 2007) and Australia (Reference Liddicoat and ScarinoLiddicoat & Scarino, 2010). As all major anglophone countries are now reporting language learning crises (Reference Lanvers, Cunningham and Hall (eds.)Lanvers et al., 2021), trends suggest that we are facing the fulfilment of the prophecy – pronounced as early as 1996 – that English speakers will be the only monolinguals left (Reference Skutnabb-Kangas, Hellinger and AmmonSkutnabb-Kangas, 1996). Across many anglophone contexts, compulsory schooling in LOTE has been eroded over the past decades (Reference LanversLanvers, 2017a), and uptake of LOTE tends to lag behind official LEP targets.

In the UK, uptake of foreign language study has been reported as below target for over two decades now (British Academy, 2020; British Academy et al., 2020; British Council, 2017). In England, the government is currently on track to fail for a second time to meet its language education target for foreign language engagement, namely that 90 per cent should learn a foreign language up to the age of sixteen by 2025 (Reference Lanvers, Cunningham and Hall (eds.)Lanvers, 2021). Scotland’s national centre for languages reports a continual decline in uptake, of European languages especially, since Reference Lanvers2012 (SCILT, n.d.). Recent policy changes to increase uptake at secondary level have as yet to make an effect on uptake (SCILT, n.d.). In Wales, the decline of FL uptake at the secondary level is more pronounced than in England (British Council, 2019). In Northern Ireland, uptake of FLs at age 14–16 has fallen by 19 per cent since 2010 (British Council, 2021). In Wales and Northern Ireland, Welsh and Irish respectively do not count towards a FL, partly explaining the low FL learning record in these nations. In Ireland, FLs were not compulsory at upper secondary level until very recently, and it is too early to determine if the new Languages Connect LEP will help stem the decline in FL uptake, especially of French, observed elsewhere (Reference Bruen, Lanvers, Thomson and EastBruen, 2021).

In the US, only about 20 per cent of school students leave with a FL certification (National K–12 Foreign Language Enrollment Survey Report, 2017), and only eleven states have a FL school graduation requirement. All FLs except for Spanish experienced a sharp decline over the last decades (Reference Rhodes and PufahlRhodes & Pufahl, 2014). Current language skills do not meet national requirements for trade, education, diplomacy and international cooperation (America’s Languages, 2017; Reference RubioRubio, 2018).

In Canada, official bilingual policies provide the context for high French–English bilingualism in some states, with an average of 20 per cent of Canadians reporting being bilingual in these languages. Despite governmental efforts, this percentage has not increased over the last decades, and English speakers are more likely to be monolingual than French speakers (Statistics Canada, 2023). Beyond this, Canada is one of the most linguistically diverse nations, with Mandarin and Punjabi as most common community languages (Statistics Canada, 2023) – to date, this multilingualism is not embedded in formal secondary school education.

In Australia, Asian languages, which make up the bulk of language learning at the upper secondary level, experienced a sharp decline over the last two decades (Reference BaldwinBaldwin, 2019), with uptake falling below target (Reference Bunce, Rapatahana & and Bunce (eds.)Bunce, 2012). Foreign languages at any post-compulsory phase are in decline (Reference Liddicoat and ScarinoLiddicoat & Scarino, 2010; Reference Mason, Hajek, Lanvers, Thompson and EastMason & Hajek, 2021). In New Zealand, the percentage of secondary school students aged 13+ enrolled in FL education dropped from 22.3 per cent in 2000 to 16.8 per cent in 2018 (Reference East, Lanvers, Thompson and EastEast, 2021a), dropping as students advance through each school year, an attrition similar to that observed in England.

Across different anglophone contexts, there is a sharp social divide in the uptake of FLs. This divide is now documented in the UK (Reference Lanvers, Rivers and KotzmannLanvers, 2017b), the US (Reference Cruickshank, Black, Chen, Tsung and WrightCruickshank et al., 2020) and Australia (Reference Molla, Harvey and SellarMolla et al., 2019). Learning languages other than English is often framed as a cultural asset for some privileged groups sharing the same cultural habitus, thus alienating large groups of learners not sharing this habitus (Reference CoffeyCoffey, 2018). Students in schools in disadvantaged areas may be prevented from continuing a LOTE against their own wishes (Reference BrownBrown 2019; Reference ClaytonClayton, 2022). The decline in LOTE learning is often accompanied by a reduction in formal learning opportunities of FLs (America’s Languages, 2017; BBC News, 2019). Many higher education providers struggle, for instance, to keep their languages departments viable (Reference LiddicoatLiddicoat, 2022; Reference Looney and LusinLooney & Lusin 2019; Reference Pawlak, Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk and TrojszczakPawlak, 2022; Reference Thompson, Lanvers, Thomson and EastThompson, 2021).

1.4.2.2 Attitudinal Issues

Attitudes and beliefs in anglophone countries, such as the common mantra ‘English is enough’, are hard to break, even in the face of evidence to the contrary. Poor self-efficacy for FL learning is evidenced in many anglophone contexts (Reference LanversLanvers, 2017a; Reference Looney and LusinLooney & Lusin, 2019). Negative public discourses, such as shaming learners for poor achievements, can further demotivate learners (Reference LanversLanvers, 2017a), and attempts to motivate students better via fostering instrumental orientations alone tend to have little motivational effect on English L1 (first language) learners (Reference GrahamGraham, 2022; Reference LanversLanvers, 2017a).

Political changes unrelated to language can also impact negatively on language learning. In the UK, Brexit has jeopardised the aim to increase language learning, because Britain, having experienced a language teacher shortage for several decades, relies strongly on EU nationals as language teachers (Reference BroadyBroady, 2020). Post-Brexit, these are both less willing and less able to settle in the UK. Negative commentary in journalistic outlets on the poor state of language learning in anglophone countries also deters students from FL study (Reference Graham and SantosGraham & Santos, 2015; Reference Lanvers and ColemanLanvers & Coleman, 2017) and thus widens the gap between societal needs for language skills, on the one hand, and actual language learning uptake, on the other (for the UK, see Reference Foreman-Peck and WangForeman-Peck & Wang, 2014; for Ireland, see Reference Schroedler, Sherman and NekvapilSchroedler, 2018).

Conversely, for the English speaker eager to engage in language learning, a number of hurdles are present (Reference LanversLanvers, 2016a). Learners of English are keen to practise their target language with ‘native speakers’. Thus, learners of LOTE who are fluent in English often find little opportunity to practise their target language. Furthermore, the demand to learn languages (via formal LEP) tends to be low in anglophone countries (Reference Lanvers, Thompson and EastLanvers et al., 2021a). The predicaments of English L1 language learners remain poorly understood.

In such contexts, one might predict that anglophone language learners who do opt for language study beyond the compulsory phase are highly intrinsically motivated. This is indeed corroborated in empirical studies (for the UK: Reference LanversLanvers, 2016b; Reference StolteStolte, 2015; for the US: Reference Thompson and LiuThomson & Liu, 2018; for Australia: Reference Lo Bianco and SlaughterLo Bianco & Slaughter, 2009). Even comparing learners of the same target language, for example English L1 and German L1 speakers both learning French, we observe that English L1 speakers show higher motivation than those with other L1s (Reference Howard and OakesHoward & Oakes, 2021).

1.4.3 Language Learning in Non-anglophone Contexts

1.4.3.1 Uptake Trends

In the following, I list some statistics and trends, underlining the (creeping) dominance in language learning in non-anglophone contexts. Across the European Union, language learners tend to perform better in English than in any LOTE they study, in terms of both uptake and learning outcomes (Reference Lanvers, Thompson, East, Lanvers, Thompson and EastLanvers et al., 2021b). Although formal engagement with the learning of LOTE is high at c. 60 per cent (Eurostats, 2022), learners and their parents often favour English as a foreign language, leading to a decline in the learning of French and other LOTE (Reference BusseBusse, 2017; Reference Csizér and LukácsCsizér & Lukács, 2010); across the European Union, targets for learning LOTE are not met (Reference LanversLanvers, 2024).

In many low- and middle-income countries, English is needed to access education. The proficiency levels needed in English create a systemic barrier to access to education and academic success, and mother tongue teaching is sidelined by teaching via English or larger colonial languages (Reference Kioko, Ndung’u, Njoroge and MutigaKioko et al., 2014). Political will to increase teaching via students’ L1, in line with UNESCO recommendations, is often present but progress in this respect is slow (for India, see Reference Kanna and RakeshKanna & Rakesh, 2023; for further examples from South Africa, Australasia and Asia, see Reference Menken and GarcíaMenken & García, 2010). Regarding uptake of LOTE, the lack of publicly available data makes it hard to gauge general patterns in formal LOTE engagement at the upper secondary level across wide geographical regions, except for Europe and anglophone regions. However, at post-compulsory levels, global trends indicate that Asian languages (Mandarin, Japanese, Korean) are on the rise, while uptake of traditional FLs such as French, German and Italian is waning in both anglophone and non-anglophone contexts (for higher education generally, see Reference Rose and CarsonRose & Carson, 2014; for the US, see Reference Looney and LusinLooney & Lusin, 2019; for Asia, see Reference KobayashiKobayashi, 2013).

One LEP aiming to reverse current trends is worthy of note. In China, the Chinese Ministry of Education launched a new LEP of investment and fostering of the learning of LOTE in 2016, in both upper secondary and tertiary education (Reference Gao and ZhengGao & Zheng, 2019). Notwithstanding the problems relating to the implementation of this policy and learning outcomes (Reference Gao and ZhengGao & Zheng, 2019), the policy nonetheless is a rare example of how modern language education policies explicitly aim to encourage the learning of LOTE. Currently, lack of public data on uptake and outcomes prevents a judgement on the long-term success of the policy.

1.4.3.2 Attitudinal Issues

Studies investigating motivation among dual linguistics (English and LOTE) in Europe tend to show higher motivation for English than LOTE (Reference HenryHenry, 2017; Reference McEown, Sawaki and HaradaMcEown et al., 2017), and, given the choice of learning English or LOTE, most would opt for English only (e.g. Reference DalmauDalmau, 2020; Reference Dörnyei and NémethDörnyei & Németh, 2006; Reference Ushioda and DörnyeiUshioda & Dörnyei, 2017). The preoccupation with English has been accompanied by a focus on pragmatic and instrumental rationales and motivations for language learning per se (Reference UshiodaUshioda, 2017).

Studies in China reveal how learners see learning English as necessary but learning LOTE as a further opportunity to advance their career (e.g. Reference Lu and ShenLu & Shen, 2022). As a good level of English competency is increasingly considered the norm, and necessary for academic progression, proficiency in English does not serve as well as a distinguishing marker of achievement. Thus, LOTE are becoming a ‘good to also have’ educational distinguisher (Reference Lu and ShenLu & Shen, 2022), accompanied by a social divide in LOTE mirroring that in anglophone contexts, with learners from advantaged backgrounds more likely to develop fluency in a LOTE or two, in addition to English (e.g. in Spain, Reference Codó and SunyolCodó & Sunyol, 2019; Reference RydenvaldRydenwald, 2015). Furthermore, negative emotions in LOTE learning can hamper progress among Chinese learners (Reference Li and LiuLi & Liu, 2023).

There is, to date, no evidence that LOTE learning opportunities in non-anglophone contexts are declining during the compulsory phases of language learning. Researchers should, however, stay alert to the question of whether LEP and provision of LOTE learning in non-anglophone contexts might eventually follow the pattern observed in many anglophone contexts, namely that of policy deregulation and erosion of provision.

1.4.4 Summary: Language Learning Patterns

Languages other than English learning in both anglophone and non-anglophone contexts show some similarities across educational sectors and different geographical regions: a growing motivational crisis for the learning of LOTE, especially hitherto traditional LOTE such as European languages, and LEP-uptake mismatch. The uptake patterns in formal education underscore the notion that the phenomenal success of English as a global lingua franca has contributed to the spread of a monolingual mindset among anglophones (Reference EllisEllis, 2008; Reference Phillipson and Skutnabb-KangasPhillipson & Skutnabb-Kangas, 1996). The demise of learning opportunities for LOTE at school level has sharpened inequality in access to language learning (Reference Barakos and SelleckBarakos & Selleck, 2019). Anglophone contexts face a motivational crisis with respect to LOTE, a decline in uptake, increasing gaps between declared and practised policy and an erosion of the opportunities to study LOTE in their respective education systems. Elitist tendencies among those engaged in language learning can be observed across all major anglophone countries. Many academics have called for radical changes to the way anglophone countries approach language study (Reference BroadyBroady, 2020; Reference Copland and McPakeCopland & McPake, 2021; Reference Reagan, Osborn and MacedoReagan & Osborn, 2019). To a large extent, official policies do not match policy-in-practice at the level of schools, largely because learners may opt to study subjects other than languages (‘voting with their feet’).

Current gaps between declared and practised LEP support the thesis that, so long as LEP permits the displacement of LOTE by English, it will serve rather than counter English dominance – or ‘linguistic imperialism’, to use Reference PhillipsonPhillipson’s (1992) term. Concerning the EU’s commitment to multilingual education, Reference PhillipsonPhillipson (1992: 47) observes: ‘although multilingualism seems to have become an “EU mantra”, its actual extent falls far short of an equal treatment of the Union’s official languages’. Citing the European Commission (2015) itself as evidence, he contends that the EU commitment to multilingualism has always been rhetorical rather than consequential. De Swaan is similarly critical of EU policy: ‘in the Union, too, pious lip service is paid to the ideal of multilingualism, while, discreetly, only two languages are used in practice’ (Reference de Swaande Swaan 2002: 184). In his view, giving rights to medium-sized and smaller languages – often to redress English hegemony – can often have the opposite effect to the one intended: ‘ the more languages are formally assigned equal status, the less chance they stand of holding their own against the one dominant language, usually English, sometimes French’ (Reference de Swaande Swaan, 2002: 187).

While Phillipson attributes the failure of the European LEP to a lack of political commitment and the investment needed to fight linguistic imperialism, de Swaan ascribes the responsibility more to individuals who lack interest in diversifying their language learning. Both, however, agree that current European LEP permits English dominance to ‘creep in’ because no educational institution commands sufficient power (or willpower?) to stem English dominance. So long as the intentions of declared LEP diverge from key stakeholder interests (such as learners and educators), it is unlikely that LEP alone will be able to curb English dominance.

Unwittingly or not, the success of English as a global lingua franca has skewed existing views on rationales for language learning. To motivate learners of English, utilitarian and functional rationales and motivations are often foregrounded at the expense of holistic arguments (Reference GrahamGraham, 2022). Learners of LOTE, meanwhile, face even greater motivational challenges (Reference Ushioda and DörnyeiUshioda & Dörnyei, 2017), leaving only the most determined LOTE learners with strong motivational stances persisting with their learning (Reference LanversLanvers, 2016b). Both motivational problems relate to the success of Global English. In a novel departure, this Element conceptualises both motivational challenges in the context of Global English.

In a world ‘stampeding towards English’ (Reference de Swaande Swaan, 2001a; Reference Van Parijsvan Parijs, 2020), how can we safeguard the learning of LOTE? What rationales might convince policymakers and curricula designers? Are the rationales we commonly cite suitable to motivate students? If attempts to engage learners in learning a variety of LOTE often fail to achieve their desired results, in both anglophone (Reference Lanvers, Thompson and EastLanvers et al., 2021a) and non-anglophone (Reference BusseBusse, 2017) contexts, can Global English be blamed for this? In Germany, for instance, the teaching of French is in sharp decline, while the uptake of English continues to increase (Reference SpiegelSpiegel, 2023). It may seem self-evident to ‘blame’ Global English for any decline in LOTE learning. However, languages, including English, have no agency in themselves: language users do. Thus, the precise mechanisms leading to the ‘stampede’ towards English deserve more attention. Can we clearly identify which stakeholder groups are driving this ‘stampede’? Learners? Parents? Policymakers? Conflicting interests between those preferring to learn English, or advocating LOTE, have long since reached the education sector. For instance, in German primary schools, it is customary, in border regions of neighbouring countries with different languages, to offer the neighbour’s language and not English as first FL (e.g. Danish near the Danish border, French near the French border; see Reference LanversLanvers, 2018a), a policy that has led parents to sue their local education authority for the right of their child to receive English instruction instead (Reference SpiegelSpiegel, 2007).

One explanation for the ‘stampede’ might be to point to a lack of motivation for the learning of LOTE on the part of the individual (learner or parent). This thesis conceptualises motivation for language learning as a ‘fixed quantity’: as motivation for one particular language increases, it decreases for others. Such framing contravenes modern conceptions of language learner motivation as dynamic, fluid and in constant ecological interaction with a host of internal as well as external influences (Reference GuGu, 2009). A further assumption underlying the ‘individualistic’ explanation concerns its overgeneralisation: the explanation takes as a given that most learners will be more motivated to learn language(s) of higher – as opposed to lesser – status. Section 4 discusses some learner groups that do not match this prediction.

One might also hold formal LEP accountable for the ‘stampede’ towards English and decline in LOTE learning. In this case, do LEPs merely follow (assumed) learner preferences, reinforcing the compulsory learning of English, while reducing the necessity to learn LOTE? This would portray LEP in the service of a neoliberal commodification of education (Reference Bori and CanaleBori & Canale, 2022).

In sum, blaming either individuals or LEP for the above-described trends has its limits, but both play a part: there is evidence that some learners are indeed motivated by personal advancement only when learning English (Reference BozzoBozzo, 2014), and that some LEP makers follow neoliberal principles in devising their LEP (Reference Bori and CanaleBori & Canale, 2022). Framing either LEP or learners themselves as responsible for the ‘stampede’ oversimplifies the complex interaction of policies, policy enactment at local and school level and learner motivation. In such contexts, holistic rationales for language learning can serve as a bulwark against commodification of language study.

The next part of this section discusses the question of if English L1 speakers could be framed as ‘advantaged’ by not having to learn other languages.

1.5 English L1 Speakers as Beneficiaries of Global English

Some argue that L1 English speakers are unfairly advantaged, as they need not ‘bother’ with language learning (Reference Van Parijsvan Parijs, 2020), or that they are net gainers of the Global English phenomenon (Reference HultgrenHultgren, 2020), because the English spoken in their inner circle (Reference Kachru and KachruKachru, 1992) is often perceived as a prestige and normative variety, desirable above other varieties. This section scrutinises these arguments.

Reference HaberlandHaberland (2020) and Reference WrightWright (2009) remind us that English fluency does not guarantee mutual understanding: monolingual English speakers often lack sensitivity to the difficulties of using English as a lingua franca and may use colloquialisms, idioms, local sayings and regional accents that make conversation for a speaker using English as a lingua franca difficult (Reference Jenkins, Jenkins, Baker and DeweyJenkins, 2017). Such speakers may also make reference to UK- or US-specific cultural or political phenomena and acronyms, which leave the international interlocutor baffled (Reference HazelHazel, 2016). Any purported advantage of having ‘native speaker-like’ competence (however defined) comes at a price: English L1 speakers struggle in international conversations using English as a lingua franca (Reference GilsdorfGilsdorf, 2002), partly because new and emerging forms of English are increasingly divergent from L1 speaker varieties, and partly because they have often had little opportunity themselves to practise cross-linguistic and cross-cultural communicative strategies that tend to develop alongside formal FL learning. Most importantly, however, since future varieties of English are increasingly being shaped by second-language speakers (Reference WeiWei, 2020), any ‘L1 English speaker advantage’ in lingua franca communications seems doubtful.

Thus, it is timely to ask if English L1 speakers are indeed well served by being ‘relieved of the burden’ of language learning (Reference Van Parijsvan Parijs, 2020). Much like the cyclist ‘relieved’ of the cycle commute to work by opting for the bus, the indolence thereby gained – or freedom, depending on your perspective – comes at a price. Monolingualism is only increasing among L1 speakers of English (Reference Lanvers, Cunningham and Hall (eds.)Lanvers et al., 2021; Reference Skutnabb-Kangas, Hellinger and AmmonSkutnabb-Kangas, 1996), not in other language communities, and these monolinguals lose out on the social, cognitive and educational advantages that multilingualism brings with it (Reference BakBak, 2016). The ‘English speaker advantage’ reveals itself to be most valid if embracing a monolithic view of English (Reference Pennycook and KirpatrickPennycook, 2020), viewing English as a fixed entity with normative ‘inner circle’ standards (Reference KachruKachru, 2006). Future varieties, however, including future high-status standards of English, will be determined by their users – and these are increasingly second- rather than L1 speakers.

The next section asks if current attitudes to the dominant lingua franca can also be found in the past.

1.6 Attitudes to Learning Lingua Francas: A Historical Outlook

Reference OstlerOstler (2005: 13) reminds us that world languages and lingua francas may come and go. The future of any lingua franca, however powerful it might seem at a particular historic moment, depends on a myriad of factors including demographic migration, access to language education and, increasingly importantly, communication technology. This brief historical excursus does not offer a like-for-like comparison between past lingua franca and Global English, nor does it offer any predictions regarding the future of Global English. Rather, it examines speakers’ attitudes to historic lingua franca, including learning them.

As far as linguists are able to document, lingua francas, in the widest sense of a language used between groups who have no language in common (Reference BernsBerns, 2012), have existed for at least two millennia (Reference NolanNolan, 2019), and multilingualism was a well-known phenomenon in antiquity (Reference Schendl, Hernández-Campoy and Conde-Silvestre (eds.)Schendl, 2012). The use of lingua francas has often benefited humankind, fostering the exchange of ideas, culture and science, as the use of Greek in early antiquity demonstrates. The Greek language was considered linguistically and culturally superior to any other (Reference AdamsAdams, 2019), and Greeks generally did not feel the need to learn any languages other than their own (Reference MomiglianoMomigliano, 1975). The term barbarism was coined and applied to any incomprehensible, foreign language, as well as to incompetent use of the Greek language (Reference HallHall, 1989).

With changing power dynamics within the Roman Empire, Greek culture and language became increasingly challenged (Reference AdamsAdams, 2003), most vocally by Cicero (Reference FögenFögen, 2000). Although ancient Greek continued to be of great importance for the educated elite for centuries to come (Reference LeonhardtLeonhardt, 2013), speakers of Greek were increasingly compelled to add Latin to their repertoire (Reference Dickey, Archibald, Brockliss and GnozaDickey, 2015). Competence in Latin became a commodity for upwards social mobility, and desirable cultural and social capital (Reference AdamsAdams, 2003).

This changed as the power dynamics of the Roman Empire shifted. The – to Romans, uncomfortable – asymmetry between Roman political and military prowess, and their nagging sense of cultural and linguistic inferiority vis-à-vis Greek (Reference AdamsAdams, 2003), was increasingly challenged, most eminently by Cicero (Reference FögenFögen, 2000). For those using Latin in antiquity, however, the notion of being disadvantaged by having to communicate in this second language (L2) was anathema. Like Greek, Latin continued to be learned and used long after the end of the Roman Empire, including in areas never occupied by the Romans (Reference LeonhardtLeonhardt, 2013).

Both Latin and Greek survived as elite lingua francas for centuries, mainly thanks to meticulously guarded codification and, in teaching, adherence to a classical canon of texts, using traditional teaching methods. The codification of Latin is perhaps best illustrated by the sixteenth-century vogue for ‘Ciceronianism’, according to which only those words that were used by the classical author were deemed to be ‘good enough Latin’ to be used in teaching and writing (Reference LeonhardtLeonhardt, 2013). Furthermore, in Europe, both French and Spanish gradually gained prestige from early modernity onwards (Reference LópezLópez, 2018), while the English language was at times described as ‘passe Dover, [is] woorth nothing’ (John Florio, 1578, cited in Reference LópezLópez, 2018: 55).

Through much of human history, then, multilingualism in prestige languages was a desirable asset for those holding privileged positions, with strongly codified prestige languages functioning as lingua francas, used alongside regional languages. In the seventeenth century, as nationhood became increasingly linked to linguistic identity, the powerful association between the nation-state and its language gave rise to the notion that monolingualism, rather than multilingualism, was an advantaged status. Indeed, according to Reference GramlingGrambling (2016), this was the point when monolingualism was ‘invented’. The notion served to sustain the hegemony of colonial powers and educated elites (Reference GramlingGrambling, 2016). The following quotation by the seventeenth-century French essayist Dominique Bouhours expresses the sentiment of monolingual superiority succinctly:

On parle déja François dans toutes les Cours de l’Europe. Tous le étrangers qui ont de l’esprit, se piquent de sçavoir le François; ceux qui haïssent le plus nôtre nation, aiment nôtre langue; … il n’y a guères de païs dans l’Europe où l’on n’entende le François, & il ne s’en faut rien que je ne vous avouë maintenant, que la connoissance des langues étrangers n’est pas beaucoup nécessaire à un François qui voyage.

People are already speaking French in all the courts of Europe. All foreigners who have some intelligence are keen to know French, and those who most hate our nation, love our language … there is hardly a country in Europe where one does not understand French, and there is no denying what I confess now, namely that the knowledge of foreign languages is not really needed by a travelling Frenchman.Footnote 1

A simple substituting of the word French with English would suffice to update this quotation for the twenty-first century. Similar language-chauvinistic attitudes can be found in other contexts (e.g. Reference García BermejoGarcía Bermejo, 2021). The exercise of comparing historical and current monolingual hegemonic attitudes may serve as a reminder – if it were needed – of the fragile status of any global language, when viewed longitudinally. This brief reflection on the status of past lingua francas, and attitudes towards language learning, has illustrated a number of characteristic dynamics that might apply to the current status of English, or not, as follows.

Being monolingual in a prestige lingua franca has historically been linked to a linguistic and cultural elite (Greek) or nation-state ideology. With changing political power dynamics, different language skills arise, a point at which monolinguals become disadvantaged. In today’s context, this means that multilinguals rather than English monolinguals are better positioned to adjust to language shifts towards new prestige varieties, should the need arise. Furthermore, historically, learners of lingua francas tended to see language learning not as a burden, but rather as a privilege, permitting social betterment. Here, we observe a similarity to English today in that many learners of English are motivated by the professional and personal advantages this language might afford them (Reference Lamb, Csizér, Henry and RyanLamb et al., 2019), while motivation for learning other languages declines (Reference BusseBusse, 2017). In short, for the minority of speakers of an elite lingua franca as (part of) their L1, learning other languages has previously been dismissed as superfluous, while opportunities to learn a lingua franca have always been framed positively.

However, mechanisms of diffusion, teaching and learning English differ substantially from learning past lingua francas. In today’s English learning world, both elitism and standardisation, although not absent, are on the wane (Reference Houghton and HashimotoHoughton & Hashimoto, 2018). Informal learning of English is greatly facilitated by the digital revolution, with boundaries between formal and informal learning, leisure and compulsory learning, institutional learning and self-study becoming ever more blurred (Reference SockettSocket, 2014). These key differences in learning opportunities and modes of learning provide something of an equaliser. Access to the learning of a global lingua franca has never had such a low entry point as access to English has today – even when acknowledging wide geopolitical differences in both accessibility to, and quality of, education. Access to free online resources is increasing (Reference ShearsShears, 2017); varieties and standards are becoming not only increasingly diverse but also increasingly unpredictable. This diversification precludes predictions as to if and when the language might lose mutual intelligibility, causing it potentially to break up into different languages (although such predictions exist; see Reference Jenkins, Jenkins, Baker and DeweyJenkins, 2017).

Furthermore, English currently benefits from neither unified codification (Reference LeonhardtLeonhardt, 2013: 16) nor strong institutional control, such as what the Catholic church offered for Latin. Controversies around varieties and standards, including the native speaker debate, abound in the multibillion-dollar business that is TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages). Publications in journals such as English Today, World Englishes, and TESOL Quarterly illustrate this. Thus, while it is estimated that one third of the world’s population will be involved in learning English in the near future (CEFR, 2020), there is no agreement on what counts as English. The dual impact of Covid-19 and the rise of online learning has made both the TESOL market and the English varieties taught more diverse, dynamic, fast changing and unregulated than ever (Reference Gogolin, McMonagle, Rauch and LesemanGogolin et al., 2020).

In brief, the English L1 speaker could indeed be described as advantaged today in certain elite contexts, such as academic publishing – an advantage, however, that is subject to change the more English L2 speakers drop aspirations to adopt English L1 norms, and the more English is influenced by L2 speakers.

This historical excursus concludes with the observation that current attitudes towards learning and speaking a lingua franca do indeed find echoes in history. However, with respect to dissemination and support mechanisms for the lingua franca, significant differences have emerged. The lack of central control over codification and the mechanisms for learning and teaching English is unprecedented and serves as a warning to tread carefully when comparing the fate of past lingua francas to that of English. Current proliferation of varieties of English makes it hard to predict which variety of English – if any – learners might consider most worthwhile for investing in in the future. Lingua francas come and go, and at the present moment English is changing faster than other current lingua franca such as Spanish or Arabic (Reference McWhorterMcWhorter, 2011). In an increasingly multilingual and globalised world, the one certainty about global language constellations and the forms taken by the lingua francas we have is that both will change, in status, form, and usage. Individuals and societies will need to adapt to these changes. In the current context, individuals versed in multilingual rather than monolingual practices will have the advantage of linguistic adaptability.

1.7 Terminologies

Perhaps more than other disciplines, the dynamic and fast-moving discipline of applied linguistics has its share of disputed terminology and definitions. From the ‘native speaker’ debate (Reference Isaacs and RoseIsaacs & Rose, 2021), to discussions about the term English versus Englishes (Reference Rose and GallowayRose & Galloway, 2017) or World Englishes, to the meaning of English as lingua franca (ELF) (Reference Bolton, Nelson and ProshinaBolton, 2019), this Element inevitably touches upon linguistic conceptions and terminologies that have given rise to fundamental controversy. This section clarifies the terminology used here.

1.7.1 Anglophone and (Non-)Anglophone Contexts

Here, anglophone contexts are defined as those where the majority of the population grows up with English as (part of) their first language(s) and uses this language for both daily business and official communication, although all anglophone countries are de facto highly multilingual. In line with this definition, the EU, a pan-national entity where most of the population does not use English to conduct both daily and official business, will be classified as ‘non-anglophone’, while the US will be considered as anglophone. Likewise, for pragmatic reasons, anglophone countries are defined here as countries where most of the population grows up with English as (part of) their first language(s).

1.7.2 Englishisation, Englishising

These terms are used to denote the phenomenon whereby English is used in contexts where hitherto other languages were used. Thus, it can cover a wide range of linguistic phenomena, such as:

an increase in the use of English loan words and all forms of translanguaging involving English

the move towards using English as a medium of instruction

in LEP, greater emphasis on the development of English rather than LOTE

in education institutions, curriculum and staffing changes favouring knowledge of language, linguistics and culture associated with English

1.7.3 Motivation in Language Learning

It has often been argued that motivation for learning languages is somewhat unique compared to learning other subjects (Reference Ushioda, Mercer, Ryan and WilliamsUshioda, 2012) in that language learning offers the potential for widening social horizons, for access to different cultures and for developing new facets of identity. This complexity is undoubtedly one of the reasons for the plethora of theoretical approaches and empirical works on the topic (for meta reviews, see e.g. Reference Aryadoust, Soo and ZhaiAryadoust, 2023; Reference Mahmoodi and YousefiMahmoodi & Yousefi, 2022), which makes it all the more important to clarify the understanding of language learner motivation for the purpose of this Element. Space precludes a full discussion of the relative merits of currently dominant L2 motivation theories (for a discussion, see e.g. Reference Lamb, Csizér, Henry and RyanLamb et al., 2019), but two features common to the dominant theories currently used in research stand out: a basic extrinsic–intrinsic continuum dimension, and a psychosocial dimension. In other words: all L2 learning motivation theories agree that (1) individual learners personally identify with reasons for language study to very different extents, and (2) the social environment, ‘significant others’ and the wider sociocultural environment influence learners greatly. These minimal premises for L2 motivation, supported by the current L2 motivation literature, serve as the basis for conceptualising L2 in this Element and for recommending pedagogical practices to promote learner motivation (Section 4). As a result, although one motivational theory is preferred over others (self determination theory), the pedagogical recommendations in this Element are designed to be compatible with all currently dominant L2 motivation theories.

1.7.4 Languages Other than English (LOTE)

Despite its intended neutrality, LOTE is inadequate in its anglocentricity, juxtaposing some 7,000+ existing languages in the world against one language, which, moreover, is not even the first or second most spoken language as L1 in the world (Ethnologue, 2019). Despite criticism of the term (Reference CunninghamCunningham, 2019), there is no agreement on alternative(s) to it. Introducing alternative terminology is possible, of course, but at the expense of comprehensibility and accessibility. Loathed or liked, the term LOTE is now established, and alternative nomenclature is unlikely to successfully replace existing terms. The use of alternative terminology risks marginalising and fragmenting academic discourse. Moreover, it is appropriate in this context in that learning of English and LOTE are explicitly contrasted. Thus, the term LOTE is used here in the tradition of linguistic reclaiming from negative connotations, such as in feminist linguistics (Reference GodrejGodrej, 2011).

1.7.5 L1, L2, LX, FL, Learners of English, Learners of LOTE

The debates on how to label the language competencies of individuals, in particular the language acquired as an infant, are well into their third decade (Reference CookCook, 1999) and show little sign of abating. Avoiding the term ‘native speaker’ for all its infelicitous connotations (Reference Isaacs and RoseIsaacs & Rose, 2021), the question nonetheless arises of how to refer to the language competencies an individual develops via informal exposure in infancy, as opposed to any other languages learned subsequently, whether informally or formally. A common practice in linguistics is to use numerical ordering to indicate the chronology of acquisition: L1 versus L2, L3 and so on, in an attempt to eschew value judgements about an individual’s proficiencies in any specific language. This practice is adopted in all contexts where an order of language learning can be assumed, based on context and LEP. In Germany, for instance, requirements of language learning are often expressed as ‘first foreign language to be introduced’, ‘second foreign language to be introduced’ and so forth, often leaving some freedom as to which target languages these should be. The label ‘L1’ is open to criticism similar to that of ‘native speaker’, with respect to connotations of proficiency and order of acquisition. It is an inadequate descriptor of multilingual L1 acquisition, interrupted and fragmented L1 acquisition, and so on, as often experienced by children, for instance those raised in migrating families. The canonical ordering poses a similar problem for further languages, in that it falsely connotes a neat chronology in which languages were/are learned. Reference DewaeleDewaele (2018) proposes the terms L1 and LX, the former describing a first language, usually mastered at a high level of competency, and the latter for any subsequently learned language, to avoid such misrepresentations. This practice is adopted here, with some important demarcations: the term ‘L1’ is understood as any language(s) a given speaker is first exposed to and acquires as an infant. Thus, ‘English L1’, for instance, is to be read as shorthand for any speaker who has this language either as the sole or one of their first languages. Furthermore, ‘LX’ will be used to describe any language learned via formal schooling, reflecting the Element’s focus on LEP in the school sector. The LX will only be afforded a specific number (L3, L4 etc.) if the order is clearly identifiable via LEP, as for example in German LEP. The term foreign language (FL) is used here to describe any language(s) acquired via formal schooling. Finally, the terms ‘learners of English’ and ‘learners of LOTE’ are not to be understood as mutually exclusive. Indeed, Section 4 dedicates a section to the problem of motivation in learners simultaneously acquiring English and LOTE.

1.7.6 Polity

Reference Kaplan and BaldaufKaplan and Baldauf (1997) stipulate that LEP needs to be captured at the level of polity, that is, the entity that is responsible for LEP and existing practices and preferences. Language education policymakers thus have agency in language learning, in the sense of deciding who may, or need to, learn what language to what level, and how to justify these policies as part of a complex ecological mesh of sociocultural and political factors.

1.7.7 Plurilingualism and Multilingualism

This Element adopts the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR, 2020) definition of plurilingualism: the ability on the part of the individual to use several languages. Conversely, multilingualism is used to describe this ability for a geographical area, that is, the handling of more than two languages by some or all members of a society (Reference Aronin and O’LaoireAronin, 2006: 3). Both terms are used according to CEFR definitions here.

Both the multilingual and translanguaging turns in applied linguistics foreground the plurilingual learner identity in any language learning processes. These paradigm shifts mandate for all language knowledge to be validated equally in learning contexts. Section 2 expands further on how we might assist educators and learners towards a positive validation of all language skills, using the recent framework of dynamic language constellations.

1.7.8 Rationale for Language Learning

One of the curiosities of the LEP literature is that the term rationale is often used but seldom defined. Here, rationale is used in the dictionary sense (Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d.) of logical reasons; thus, LEP rationales serve to legitimise and justify policies using rational arguments.

1.7.9 World Englishes, Lingua Franca, Global English, World Language

Given the plethora of publications and ever-expanding terminologies describing growth in the use and learning of English, a pragmatic restriction to commonly used terminology, in its most widely accepted definition, is called for. A lingua franca is understood as a variety used for communication between speakers of different L1s (Reference LeonhardtLeonhardt, 2013). The term world language is used here to refer to a language of high global status, often used in high-status domains, such as politics, business and commerce, travel, high culture, and academia. The term World Englishes describes varieties of English used around the globe, giving no preference or partiality towards one variety or another (Reference SeargeantSeargeant, 2010). Finally, the term Global English is used here, again following Reference SeargeantSeargeant’s (2010) taxonomy, to underline the use of English beyond the inner circle countries and in global professional contexts, in the widest sense. In other words, Global English is a phenomenon powered by Englishisation, in all its forms, including the learning of English where, conceivably, none had taken place previously.

1.8 Section Summary

In a context where one language, by virtue of its global status, has the power to influence the LEP of all other languages, it is timely to consider what rationales for language learning might offer solutions to the challenge of English dominance. The historical excursus served to underline the ephemeral nature of lingua franca, and the advantages of preparedness for global linguistic changes. This section also outlined commonalities between anglophones and non-anglophones regarding the effect of Global English: as the learning of English is prioritised over that of learning LOTE – by learners themselves and/or by LEPs. There are also signs that the learning of LOTE is becoming increasingly elite, especially in anglophone and increasingly in non-anglophone contexts. In anglophone contexts, neither the ‘English is enough’ fallacy (Reference MartinMartin, 2010) nor elitism in LOTE learning (Reference Muradás-TaylorMuradás-Taylor, 2023) show signs of fading. These trends seem to support de Reference de Swaan, Sternberg and Ben-RafaelSwaan’s (2001b) thesis that learners are mostly interested in learning high-status languages. Meanwhile, multilinguality, including in language classrooms, is growing globally, often due to mass migration. As a result, education systems and formal language education are increasingly diverging from the lived realities of multilingualism today (Reference Lo Bianco and AroninLo Bianco & Aronin, 2020: 40).

A rethinking of rationales for language study can help address this gap. Helping learners appreciate a wide range of reasons for language study is as important as language instruction itself and can help learners appreciate the value of learning a variety of languages. Thus, rationales can do more than offer a (necessary) justification for the space accorded to languages in the curriculum and learners’ overcrowded timetables. The question Why teach or learn languages? supersedes operational questions such as How? At what age? and To what level? These can only be addressed meaningfully once the first is answered. Too often, however, neoliberal approaches to education drive language education policymakers to address questions of how before why.

A crucial consideration in rationalising language learning for the twenty-first century is if English can somehow be ‘blamed’ for current language learning uptake trends. The next section offers a critical debate on this issue.

2 Framing English as a Killer Language

It happens all too often – people regret that their language and culture are being lost but at the same time decide not to saddle their own children with the chore of preserving them.

Section 1 has argued that, globally, provision and uptake of formal language education are at a crossroads, in several respects: declared aims in LEP are not matched by actual uptake, and neither declared LEP nor uptake match the reality of our increasingly diverse and multilingual world (Reference Banks, Suárez-Orozco and Ben-PeretzBanks et al., 2016). This section scrutinises the link between Global English and LOTE learning in more detail. As a first step towards unpacking any assumed link between patterns in the learning of LOTE and of English, the next section engages with the question of whether Global English can be framed as responsible for the decline in LOTE learning.

2.1 Relating Global English to the Decline in LOTE Learning

The answer to the question of whether Global English is responsible for a decline in LOTE learning depends to a large extent on the degree of partisanship or neutrality afforded to the English language, as both a lingua franca and a favourite FL for learners. The positioning of English (e.g. as a commodity, a threat, a neutral affordance) influences stakeholders’ view of the relative merit of learning English and shapes LEP. Declared LEPs might favour English explicitly, for example by increasing the compulsory element of English L2 in the curriculum or, implicitly or even inadvertently, by liberalising choices in the learning of L2s (Reference PhilipsonPhillipson, 2017b).

Similarly, the stance someone takes towards the phenomenon of Global English shapes how they explain the language learning crises in anglophone contexts. For some, the crisis is taken as evidence of xenophobia, native-speakerism and a chauvinistic and imperialistic stance towards English. This explanation, plausible at first glance, becomes problematic when looking more closely at who ‘decides’ to learn languages – or not. Who has elected to deprioritise language learning in anglophone education systems? Do learners actively ‘decide’ not to learn a LOTE and, if so, why? In the UK’s education systems, for instance, a range of systemic disincentives prevent students from continuing with FL study beyond the compulsory phase (Reference LanversLanvers, 2018b), with some forced to discontinue their study (Reference ClaytonClayton, 2022). Thus, the ‘choice’ to study a FL is often conditioned by forces outside the remit of the students themselves. There are also few signs that English L1 speakers harbour more chauvinistic attitudes towards their first language than any other L1 speakers might do towards theirs: all speakers show the tendency to prefer their own language (Reference GarretGarret, 2010). In sum, there is little evidence to support the claim of ‘English exceptionalism’, in the sense that English L1 speakers are more averse to language learning per se than other L1 speakers.

There is, however, evidence that, like other L1 speakers, English L1 speakers often show a preference for their native variety, rather than a variety emerging out of ELF use (Reference Subtirelu and LindemannSubtirelu & Lindemann, 2016), a fact that often contributes to miscommunication between L1 and L2 users of English (Reference HazelHazel, 2016). As argued in Section 1, monolingualism tends to equip L1 English speakers poorly for ELF communication. To date, the few empirical studies investigating the issue suggest that many anglophones are aware of these communicative limitations (Reference Cruickshank, Black, Chen, Tsung and WrightCruickshank et al., 2020; Reference LanversLanvers, 2012).

In sum, both the notion of English L1 speaker ‘advantage’ and the notion of English as the killer language of LOTE need revisiting. To scrutinise both notions further, three models of global language constellations will be presented. Many such models exist (e.g. Reference KachruKachru, 2006). The three models presented here have been chosen for heuristic purposes: the models offer maximally contrastive answers to the questions of whether, and how, Global English might be bringing changes to the learning of English, on the one hand, and of LOTE, on the other. They are:

Linguistic imperialism

Global language system

Dominant language constellations

The models frame Global English, respectively, as inherently hegemonic, inherently utilitarian or as part of a dynamic unitary system. Each model is examined from the perspective of the language learner: learners of English and learners of LOTE (including English L1 learners), asking how these learners are positioned within these models in the context of Global English; are they beneficiaries or losers? Thus, this section discussed the level of agency the different models might ascribe to language learners themselves.

2.2 Linguistic Imperialism

For some linguists (Reference PennycookPennycook, 1994; Reference PhillipsonPhillipson, 2003), English has long ceased to be, and never will be, a neutral lingua franca. In Phillipson’s view, standards of English, access to language learning and status hierarchies of different Englishes remain intrinsically linked to, and representative of, socio- and geopolitical inequalities. While others (e.g. Reference HultgrenHultgren, 2020) consider today’s ubiquity of English as a sign of the language’s equalising potential, if not its de facto equalising quality, Reference PhillipsonPhillipson (1992: 47) sees English dominance as safeguarded by the ‘establishment and continuous reconstruction of structural and cultural inequalities between English and other languages’. Any form of linguistic imperialism is viewed as a form of linguicism, defined as ‘ideologies, structures and practices which are used to legitimate, effectuate, regulate and reproduce an unequal division of power and resources (both material and immaterial) between groups which are defined on the basis of language (Reference Phillipson and Skutnabb-KangasPhillipson & Skutnabb-Kangas, 1996: 667).

Reference PhillipsonPhillipson (2003) asserts that linguicism perpetuates and reinforces existing social inequality. In this view, discourses that frame English as neutral (lingua nullius – nobody’s language), as espoused by the British Council or some American politicians, contribute to linguicism and mask the vested interests of dominant powers in its proliferation.

2.2.1 Critique of Linguistic Imperialism

As detailed theoretical critiques are available elsewhere (Reference LinLin, 2013), this review concentrates on how stakeholders in language education are positioned within the linguistic imperialism model. De Swaan has criticised its strong hegemonic view of English, arguing:

Recently, a movement to right the wrongs of language hegemony has spread across the Western world, advocating the right of all people to speak the language of their choice, to fight ‘language imperialism’ abroad and ‘linguicism’ at home, to strengthen ‘language rights’ in international law. Alas, what decides is not the right of human beings to speak whatever language they wish, but the freedom of everyone else to ignore what they say in the language of their choice.

In other words, however ideologically driven some declared policy may or may not be, practised policy can never be organised in the controlled manner that Phillipson postulates. Gaps between declared and practised policy are inevitable, and, in the continual tension between top-down policy and bottom-up practice, the agency of individuals must be acknowledged. Learners might choose English, for their own betterment and that of their communities. Indeed, the most vocal criticism of Phillipson can be found among those advocates of English who highlight the liberational, life-enhancing and mobility-enhancing potential afforded by the language (Reference CanagarajahCanagarajah, 1999). Many of Phillipson’s opponents share his critical assessment of English dominance, but differ greatly in their approaches to addressing it.

Phillipson (2013), aware of such criticism, has argued that neither individuals, nor LEPs, nor the applied linguistics academic community have so far succeeded in countering linguistic imperialism. For him, inequalities in access to learning English and the continuing higher status of inner circle (Reference KachruKachru, 2006) varieties of English are mechanisms that perpetuate linguistic imperialism.

In sum, advocates of the linguistic imperialism model tend to contend that the language is ‘imposed’ upon learners against their will and thereby afford little agency to the individual learner as agents of LEP. The position reveals a conceptualisation of LEP as static. As Reference CanagarajahCanagarajah (1999) remarks, Phillipson emphasises the structural at the expense of the local. If, however, we credit language users with agency to shape, propagate and form their own varieties and norms, even the learning of a language labelled ‘imperialistic’ harbours the potential for resistance. Learners may take ownership of varieties of English, distribution processes and resources in English. Free online learning resources, increasingly ubiquitous, facilitate such bottom-up processes, and learners need not replicate and reinforce dominant varieties of English (Reference Seidelhofer, Miller and ThomsonSeidelhofer, 2005). In short, language learners and users have agency.

2.3 Global Language System

The economic linguists Reference de SwaanDe Swaan (2002), Reference Grin and ArzozGrin (2008) and Reference CalvetCalvet (2006) have proposed a hierarchical global language system. In this system, only about 100 of the world’s several thousand languages are positioned as central; these are spoken by 95 per cent of the global population. Furthermore, some twelve languages (e.g. Russian, German, French, Arabic, Hindi, Spanish) achieve the status of supercentrality, reaching significance beyond national boundaries, and only one language, English, achieves hypercentral status, as a global lingua franca. Viewing language as a hyper-collective economic good, the model furthermore states that language learning mostly occurs in a centripetal direction, with most learners interested in learning languages of higher centrality than the ones they already possess as (part of) their first language(s). As a consequence, the only hypercentral language becomes the most desirable to learn. The model is a perfect example of self-reinforcement of hierarchies: any existing popularity is likely to propel a language into further popularity, and vice versa (Reference de Swaande Swaan, 2002: 5).

The model includes a mechanism for calculating the economic status of a given language in the form of its Q value (Reference de Swaande Swaan, 1993). To do so, the overall number of speakers of a language and the number of multilinguals among them are needed: the Q value of any language is calculated by multiplying the prevalence of a language (number of speakers) by its centrality (number of multilingual speakers). It thus would be in the language learner’s interest to invest time and effort into languages with a high Q value. If individuals have a choice between a higher- or lower-status language (as measured by Q value), for instance when an author needs to decide which language to publish in, economic and expediency arguments usually favour the higher-status language, while ethical and cultural arguments, such as countering hegemony and preserving diversity in cultures, might favour a lower-status language. In multilingual societies and communication systems, centrality rather than prevalence of a language will dictate which language carries a higher Q value and is likely to function as the more expedient lingua franca. Furthermore, linguistic inertia (Reference de Swaande Swaan, 2002: 18) is often responsible for a time lag between changes in political constellations and shifts in the status of various languages, including the popularity of learning a specific language, but, in many cases, power dynamics between languages ultimately align with those of the political world. The model thus predicts a continual dynamic rivalry between languages, each vying to improve its position:

The concept of a multi-tiered, hierarchical world language system provides the foundations for a political sociology of language. The dynamics of this emerging global system were generated by processes of state-formation, which led to language unification at home, and to transcontinental expansion of the language abroad. Within each constellation, group rivalry and accommodation, and elite attempts at closure, shape the division of functions between languages.

Meanwhile, L1 speakers of a high-status language such as English are framed as ‘relieved’ of the burden of language learning, often without much awareness of this privilege (‘an enviable blessing is bestowed upon them by the sheer accident of their mother tongue’, Reference de Swaande Swaan 1998: 43).

As for the issue of linguistic imperialism, de Swaan positions this rather more ethical question outside the remit of linguistics, and counters, similarly to Canagarajah, that most choices for or against a given language are determined bottom-up, by speakers themselves. For de Swaan, then, language preferences of individuals should not be subject to ethical considerations of linguistic human rights, and top-down LEPs, for the most part, try to address the preferences of most learners at most times.

2.3.1 Critique of de Swaan

In this model, competitiveness, profitability and efficiency determine global language developments, including learning trends (Reference Del Percio, Flubacher, Flubacher and PercioDel Percio & Flubacher, 2017). The desirability of a language is as calculable as the price of goods. Reference PhillipsonPhillipson (2003) observes that de Swaan borrows from neoliberal theories of international trade, of merit goods and collective cultural capital. In de Swaan’s model, learners are first and foremost agents improving their linguistic capital by acquiring high Q-value languages. The dynamics of language distribution, then, would be akin to the mechanisms that characterise social media postings, namely user-driven, bottom-up and populist, thus mostly reinforcing existing hierarchical linguistic structures. Language education policymakers, meanwhile, would be largely guided by the Q values of both L1s and L2s in play in any given context, and macro-political, economic and social factors would determine which L2s (if any) were worthwhile learning. In this model, the main task of declared LEP is to strategically align provision with individual preferences, matching maximum opportunities for individuals to develop their Q value in return for minimal investment.