1 Introduction

Overuse involves the oversupply of interventions beyond the needs of the population. It has become increasingly recognised as a problem of healthcare quality,Reference Korenstein, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Keyhani1–Reference Saini, Brownlee, Elshaug, Glasziou and Heath4 where quality refers to ‘the degree of match between health products and services, on the one hand, and the needs they are intended to meet, on the other’.Reference Berwick5 In this Element, we explore how concepts related to overuse have been variously employed across research, policy-making, and clinical practice. We highlight that much work to date has focused on identifying overuse rather than examining potential solutions to combat it – but show that even identifying overuse is not straightforward. We describe how overuse is becoming seen as a new ‘quality frontier’Reference Berwick5 and explain the challenges in designing and evaluating approaches to improvement. We discuss critiques highlighting the tension between standardised restrictive policies and individualised clinical care.

2 What Is Overuse?

Overuse has been defined as ‘the provision of medical services that are more likely to cause harm than good’Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6 and accordingly as a form of inappropriate care.Reference Alderwick, Robertson, Appleby, Dunn and McGuire7 Since the adoption of the term by the Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality in 1998,Reference Chassin8 overuse has increasingly encompassed a range of concepts, including overdiagnosis,Reference Moynihan, Doust and Henry9 overtreatment,Reference Godlee10 and too much medicine.Reference Glasziou, Moynihan, Richards and Godlee11,Reference Carter, Rogers and Heath12 It is also often linked with the concept of low-value care. However, overuse and low-value care have different origins and are traceable to different research literatures: research on overuse originated in the clinical community and has been focused on clinically orientated concerns;Reference Chassin8,Reference Brook, Chassin and Fink13 research on low-value care originated with economists and has been focused on improving system-level value.Reference Alderwick, Robertson, Appleby, Dunn and McGuire7,Reference Porter14 Concepts of low-value care in the literature are therefore often broader than those of overuse and based on priority-setting and the comparative cost-effectiveness of interventions – which may result in the classification of interventions that have significant clinical benefit as low-value due to their relative cost.Reference Baker, Qaseem, Reynolds, Gardner and Schneider15,Reference Aylward, Phillips and Howson16

In this Element we focus on overuse of healthcare interventions, broadly defined as diagnoses and treatment interventions that have negligible or no benefit to individuals and that have the potential to cause either direct harm (e.g. side effects) or other unwelcome consequences (e.g. financial or other burden of treatment) for patients, as well as wasting resources at a system or societal level.Reference MacLeod, Musich, Hawkins and Schwebke17,Reference Hensher, Tisdell and Zimitat18 We show that there are many challenges in identifying, defining, and measuring overuse, and highlight that all definitions of overuse incorporate both clinical and economic concerns to some extent.

3 Understanding Overuse

Overuse can be broadly understood as the provision of interventions that have negligible or no benefit (and may cause harm) to particular groups of patients. However, despite its apparent conceptual simplicity, the term has been used in different ways in different contexts, sometimes bringing together divergent and potentially competing ideas. Research, policy, and practice in this area have all suffered from a lack of consensus on conceptualisation, definition, and measurement, leading to challenges for stakeholders trying to strategically understand and address overuse.

Several conceptual frameworks for understanding overuse have been developed. For example, Lipitz-Snyderman and BachReference Lipitz-Snyderman and Bach19 propose attention to: trade-offs between benefits and harms, and between benefits and costs; and patient preferences (i.e. where these may be inconsistent with evidence or clinical recommendations). Chan et al.Reference Chan, Chang, Nassery, Chang and Segal20 suggest that there should be differentiation between ‘specific clinical situations or indications for which a service is considered inappropriate or of questionable clinical value’ and ‘services that may be appropriate for a specific population, such as a high-risk population, but [are] inappropriate or of negligible clinical benefit when applied to other, particularly lower-risk populations’.

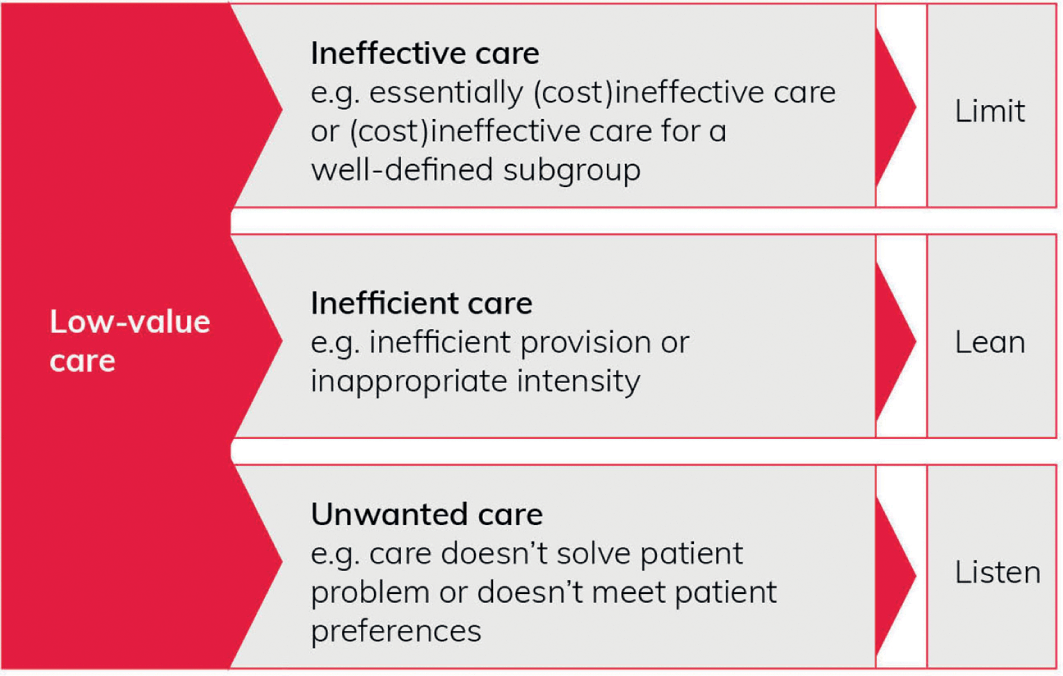

Verkerk et al.Reference Verkerk, Tanke, Kool, van Dulmen and Westert21 develop such ideas into a broad typology of low-value care, which reflects medical, system, and patient perspectives.

(1) Ineffective care: from a medical perspective, care that is ineffective (in terms of clinical benefit and/or cost) for a certain condition or subgroup of patients, according to scientific standards. Examples include antibiotics for a viral infection or routine echocardiography for asymptomatic patients.

(2) Inefficient care: from a societal (or system-level) perspective, care that involves ‘inefficient provision or inappropriate high intensity or duration’. Examples include duplication of diagnostic tests and removing stitches in hospital instead of general practice. This form of care may be effective clinically but is also considered as overuse.

(3) Unwanted care: from a patient perspective, care that ‘does not solve the individual patient’s problem or does not fit the individual patient’s preferences’. Examples include chemotherapy for a patient who prefers palliative care, or surgery for a patient who prefers conservative treatment.

3.1 Scientific Evidence of Clinical Ineffectiveness

Ineffective care can be considered as one key dimension of overuse. However, establishing unequivocal evidence of clinical ineffectiveness for particular interventions and specific patient groups is rarely easy.Reference Verkerk, Tanke, Kool, van Dulmen and Westert21 As Elshaug et al. point out in their report of 150 potentially low-value practices, ‘services that are ineffective and/or unsafe across the entire patient population to which they are applied are probably quite rare’.Reference Elshaug, Watt, Mundy and Willis22 Instead, overuse occurs along a continuum, running from ‘universal benefit’ to ‘entirely ineffective’ (see Figure 1):

Figure 1 Grey zone services

At one end of the continuum lie tests and treatments that are universally beneficial when used on the appropriate patient, such as blood cultures in a young, otherwise healthy patient with sepsis, and insulin for patients with Type 1 diabetes. At the other end of the continuum are services that are entirely ineffective, futile, or pose such a high risk of harm to all patients that they should never be delivered, such as the drug combination fenfluramine-phentermine for obesity. However, the majority of tests and treatments fall into a more ambiguous grey zone.Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6

To date, a large proportion of the work to identify and address overuse has focused on the ‘easy hits’Reference Robinson, Williams, Dickinson, Freeman and Rumbold23 – that is, those interventions with a relatively uncontentious scientific evidence base to demonstrate that they are ‘entirely ineffective’ for all, or distinct groups of, patients. But as efforts to identify overuse have become more extensive (moving beyond unambiguous cases and into the grey zone), disagreement among experts and other stakeholders has increased, with definitions, underlying principles, and interests all being contested.Reference Nassery, Segal, Chang and Bridges2,Reference Carter, Rogers and Heath12,Reference Macdonald and Loder24

In Brownlee et al.’s grey zone (Figure 1), a challenge for those seeking to identify overuse is absent or weak evidence relating to specific patient subgroups. For example, Garner et al. used Cochrane systematic reviews to identify low-value and potentially overused interventions.Reference Garner, Docherty and Somner25 But the interventions they identified were the result of ‘a lack of randomised evidence of effectiveness, rather than robust evidence of a lack of effectiveness or evidence of harm’Reference Garner, Docherty and Somner25 – or as Altman and Bland memorably express it, an ‘absence of evidence’ rather than ‘evidence of absence’.Reference Altman and Bland26 In their systematic review of nursing guidelines, Verkerk et al. were similarly unable to distinguish between do-not-do recommendations with a strong or weak evidence base.Reference Verkerk, Huisman-de Waal and Vermeulen27 Although insufficient or weak scientific evidence is also a challenge in the development of clinical guidelines,Reference Wieringa, Dreesens and Forland28,Reference Knaapen29 it is particularly problematic in the context of labelling interventions as overuse because such interventions may become targets for restriction or removal.

3.2 Approaches to Identifying Overuse

In addition to the challenges in establishing which interventions might be ineffective and thus vulnerable to overuse, methods for identifying when overuse is occurring in health systems are also diverse and lacking in consensus. One of the most widely used is the RAND Appropriateness Method, which was developed in the USA in the 1980sReference Chassin8,Reference Brook, Chassin and Fink13 in response to two main issues. First, a recognition of the limited specificity of clinical guidelines, which may recommend that an intervention is considered for a particular group of patients, but not address the conditions under which people within this group may derive limited benefit or experience harm.Reference Keyhani and Siu30 Second, a new awareness of large geographical variations in the use of some interventions.Reference Shekelle31 The RAND approach uses similar techniques to the guideline development process, integrating scientific evidence with the opinions of experts,Reference Korenstein, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Keyhani1,Reference Keyhani, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Korenstein32 but it also incorporates detailed assessments about the ‘appropriateness of performing the procedure for a comprehensive set of specific clinical circumstances or clinical scenarios’.Reference Shekelle31

Other approaches involve systematically reviewing the research evidence for individual conditions. In the UK, for instance, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has developed do-not-do recommendations based on reviews of clinical guidelines.Reference Garner and Littlejohns33 Its do-not-do database stipulates, for example, that pharmacological intervention should not be employed to aid sleep ‘unless sleep problems persist despite following a sleep plan’.34 Researchers have also undertaken marginal analyses,Reference Polisena, Clifford and Elshaug35 revisited previous systematic reviews (that were originally focused on intervention rather than potential for overuse),Reference Garner, Docherty and Somner25 and reassessed health technology assessments.Reference Noseworthy and Clement36–Reference Soril, Niven, Esmail, Noseworthy and Clement38

Practice variation studies,Reference Leape, Park and Solomon39,Reference Chen, Lin and Bardach40 which seek to identify clinical practices that vary by country, region, or individual clinician, also have a role in assessing overuse. Such studies can provide insight into potential areas of overuse (or underuse) by identifying large geographical differences between and within countries to prioritise opportunities for disinvestment.41,42 Their premise is that variation is not only due to different population characteristics, but also reflects ‘professional uncertainty’ – that is, variation in clinicians’ beliefs about the outcomes of alternative treatments.Reference Wennberg, Barnes and Zubkoff43 Findings can operate as ‘tin-openers’ – providing data from which to start the process of assessing and making decisions about overuse and underuse.Reference Schang, Morton, DaSilva and Bevan44 For example, an Australian report based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data aimed to ‘stimulate a national discussion’ about whether variation in several orthopaedic, obstetric, and cardiac procedures was warranted.45 National and international surveillance programmes on antibiotic use are another important example of extensive infrastructure being put in place to enable variation modelling.46,47 However, interventions with high levels of practice variation are often those for which the current evidence ‘does not point clearly to a right answer’Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6 on which practice is most effective, thereby creating space for different professional opinions and use of discretionary care.

Practical difficulties in trying to characterise overuse arise because of lack of data in relation to subgroups of patients,Reference Chan, Chang, Nassery, Chang and Segal20 problems separating data from routine data sources,Reference Korenstein, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Keyhani1 and a lack of relevant clinical data about symptoms and physical exam findings in electronic health records and administrative databases.Reference Levinson, Kallewaard and Bhatia48 The incompleteness of data records has also created significant challenges with interpreting evidence of overuse from one healthcare setting to another.Reference Garner, Docherty and Somner25 As electronic records make data more accessible, and suites of local indicators are developed based on evidence of overuse from professional societies and campaigns,Reference Schwartz, Landon, Elshaug, Chernew and McWilliams49–Reference Isaac, Rosenthal and Colla52 some of these challenges are being addressed. Researchers are increasingly using new methods to identify overuse within healthcare systems – for example by using algorithms to interrogate administrative databases.Reference Segal, Bridges and Chang50 In line with the underpinning scientific evidence and focus of professional campaigns such as Choosing Wisely, such work has been orientated towards tests and procedures rather than, for instance, prescribing.Reference Brett, AG and RS53

3.3 Determining Overuse in the Context of Differing Perceptions of Value

The approaches for identifying overuse highlighted in Section 3.2 are typically based on research evidence of clinical and cost-effectiveness,Reference Haynes, Devereaux and Guyatt54,55 which is consistent with the argument that ‘only evidence from clinical research has secure standing as knowledge’.Reference Upshur56 But the methods for producing standardised evidence for application in clinical practice are, of course, open to challenge.Reference Wieringa, Dreesens and Forland28,Reference Timmermans and Berg57–Reference Knaapen60 Increasingly, tensions are being recognised between standardised systems for assessing overuse and clinical judgements when applied in context. For policy-makers, determining the value of interventions requires more than scientific measures of effectiveness in the treatment of individual conditions: it also involves complex and context-dependent decisions about options, and allocative concepts of value – ‘health outcomes achieved per dollar spent’.Reference Porter14

At this system and policy level, there is frequent tension between financial and quality imperatives.Reference Williams and Brown61 Concepts of low value in this context include considerations of the comparative value of interventions given restricted budgets and allocative options, which may go beyond strictly clinical/scientific concepts. Healthcare commissioners may come under pressure, for reasons of cost, to restrict interventions and services that have been approved as clinically evidence-based.Reference Williams, Harlock and Robert62 By the same token, decisions about overuse may be influenced by the range of alternatives that are available and their associated costs and burdens. For example, surgery for minimally symptomatic inguinal hernia could be considered as overuse,Reference Malik, Marti, Darzi and Mossialos63 since this condition can be managed effectively with so-called watchful waiting. But this alternative strategy also requires clinical activity and resources, so the decision may not be straightforward. More generally, comparing surgical interventions with more conservative options (e.g. physiotherapy) is often more complex than it might initially appear, complicating assessments of overuse.

Determining value may also involve considering the (potentially conflicting) interests of different stakeholders. Antibiotic overuse is a particularly complex area: as well as debates about what constitutes appropriate use in clinical practice,Reference Tarrant, Krockow and Nakkawita64 there is difficulty in balancing the value of antibiotics to individual patients in the short term against the longer-term risk to society of growing antimicrobial resistance. Controversies about managing antibiotic overuse point to the need for both responsible use in terms of optimising clinical outcomes, and broader stewardship programmes that protect the efficacy of antibiotics for wider society and patients of the future.Reference Dyar, Obua and Chandy65

Further complexity arises when the views of patients and the public are factored into thinking about what counts as overuse. An increasingly influential view is that identifying an intervention as low value should be based on the features of the individual encounter, rather than done in a general way outside of a specific situation.Reference Korenstein66 This and similar arguments emphasise that individual patient needs and preferences should be core to decision-making about the value of interventions in practice.Reference Greenhalgh, Howick and Maskrey59,Reference Hollon, Areán and Craske67,Reference Heneghan, Mahtani and Goldacre68 In this individualised context, the most important outcomes for some patients may diverge from those that are prioritised within the scientific frame of knowledgeReference Pathak, Wieten and Djulbegovic69 (see Box 1). While patients may in many cases opt for more conservative options when informed about the likelihood of benefits and potential harms,Reference Stacey, Légaré and Col74 this approach can be problematic if patients seek interventions that are not deemed appropriate within the healthcare system. This can be seen in public calls for population-based screening programmes for conditions for which existing research evidence does not support screening, for example.

Box 1 Balancing the possible benefits and harms of breast cancer screening

Screening for breast cancer with mammography is often discussed in the overdiagnosis and overtreatment literature. This is because of its tendency to identify anomalies that would not have gone on to cause a problem for the individual concerned, but are then subject to intervention.

A 2011 Cochrane review of breast screening suggested that for 2,000 women screened over a period of 10 years, one would have her life prolonged but an additional 10 would be treated unnecessarily.Reference Gøtzsche and Jørgensen70 In 2012, the Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening came to the view that while screening did reduce breast cancer mortality, there was an associated cost of overdiagnosis for other screening participants.71 The review placed the figure at about three overdiagnosed cases identified and treated for every one breast cancer death prevented.

The balance between possible benefits and harms has led to calls for better information for those invited to take part in breast screening – in particular, for information clearly stating the potential for overdiagnosis and subsequent overtreatment. In Australia, a randomised controlled trial of a decision aid including information on overdiagnosis to support informed choice about breast cancer screeningReference Hersch, Barratt and Jansen72 suggested that the additional information increased the number of women making an informed choice about whether or not to have screening. It also indicated that being better informed might mean women were less likely to be screened. However, other work (by several of the same authors) on women’s harm/benefit trade-offs has suggested that people have high tolerance for overdiagnosis, with around half of women reporting that they would always be screened, even at a 6:1 overdiagnosis-to-death-avoided ratio.Reference Stiggelbout, Copp and Jacklyn73

Ultimately, identifying what is deemed appropriate use cannot be seen as an entirely scientific or neutral enterprise. Instead, it is a social process with multiple political, economic, and relational dimensionsReference NE, CH, TD, MB and Wisely75,Reference Hasson, Nilsen and Augustsson76 (see Box 2). Despite Porter’s argument that a scientific and economically calculated ‘value for patients’ should take precedence over the ‘myriad, often conflicting goals’ of stakeholders,Reference Porter14 the practices involved in identifying overuse (and underuse) are inevitably complex and social. Overuse has been related to payment systems (e.g. fee for service), but also to interrelated patient, clinician, and healthcare system factors. Patterns of overuse can be surprising when, for example, system change shapes new behaviours.Reference Mafi and Parchman89

Box 2 Controversies in defining appropriate use – an example from cardiovascular disease prevention

Controversies around defining and identifying overuse are particularly evident in debates around the use of preventative medications in healthy people. In recent years, medications targeting cardiovascular risk conditions (e.g. hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus) or calculations of overall risk have become a key feature of cardiovascular disease prevention.77–79 The widespread prescription of these interventions for primary prevention (i.e. to people without history of cardiovascular disease) is intended to save both lives and money.80 For example, the National Health Service (NHS) Health Check programme, which has operated in England since 2009, aims to address underuse of preventative medications by identifying people to whom they should be prescribed, and quality measures in general practice incentivise such prescribing.Reference Digital81

However, the widespread use of these preventative medications and apparently rigid adherence to guidelines in this area have been challenged.Reference VM, JP and HH82 Some clinical leaders claim that preventative medications may do more harm than good, with side effects outweighing potential predicted future benefits in many cases and broader harms (e.g. psychological, treatment burden) emerging from diagnostic labelling.Reference Heath83,Reference Hutchins, Viera, Sheridan and Pignone84 The widely publicised controversy over statin medications (coined the ‘statin wars’) illustrates such contentions,Reference Husten85 with critics highlighting their widespread prescription as a case of overuse rather than underuse.Reference Kendrick86,Reference Newman and Redberg87 Others have disputed the value of the NHS Health Check programme, arguing that it diverts resources to population groups in least need.Reference Capewell, McCartney and Holland88

At the heart of the debate are competing framings of the benefits and harms of medications and ideas about how standardised knowledge from research and guidelines should be translated into practice.

3.4 Recognising Overuse as a Quality Problem

Notwithstanding the debates about defining and measuring it, overuse is increasingly seen as a problem for health systems, populations, and patients. Researchers have estimated that ‘around 20% of mainstream clinical practice brings no benefit to the patient’.90 Although such estimates are largely based on the US healthcare system, researchers working in other countries have reported similar findings. An international review of overuse estimates that ‘approximately a third of all patients (between 20% and 33%, depending on the study), receive treatments or services that the evidence suggests are unnecessary, ineffective or potentially harmful’.Reference Ellen, Wilson and Vélez91 Individual studies suggest rates of overuse may be very much higher for some interventions, in some contexts – with one study in China finding that 57% of patients had been prescribed inappropriate antibiotics.Reference Berwick5

Overuse has sometimes been identified as a particular problem in high-income countries,Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6,Reference Keyhani, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Korenstein32 but patterns of overuse – and underuse – are not always simple. In 2017, The Lancet published a series of articles on ‘right care’, based on studies of overuse around the world.Reference Saini, Brownlee, Elshaug, Glasziou and Heath4–Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6,Reference Saini, Garcia-Armesto and Klemperer92–Reference Elshaug, Rosenthal and Lavis95 It highlighted that overuse and underuse (the latter defined as ‘the failure to use effective and affordable medical interventions’Reference Glasziou, Straus and Brownlee94) were both widespread and should be understood and addressed in parallel.Reference Saini, Garcia-Armesto and Klemperer92 Overuse and underuse may coexist within the same health economies, across the spectrum of different intervention types and/or for a single intervention across different patient groups. Overuse and underuse may be present in both high-income and low-income countries. Overuse has been (and continues to be) a persistent challenge even in low-income countries and in communities with limited access to healthcare services, where overuse may be a response to poor living conditions or limitations of available healthcare services.Reference Berwick5,Reference Jain96,Reference Willis and Chandler97

Concerns about overuse have become increasingly prominent in the healthcare community, particularly as increasing numbers of studies show that overuse has potentially major consequences for patients – including costs, emotional distress and anxiety, physical harms from side effects, or other adverse eventsReference Moynihan, Doust and Henry9,Reference Heath83,Reference Hicks98–Reference Moriates100 – and for the sustainability of healthcare systems.3,Reference Berwick and Hackbarth101 Addressing overuse has recently been positioned as a new ‘quality frontier’ in international work to improve healthcare quality,Reference Berwick5 being linked with the Institute of Medicine’s dimensions of quality.102,Reference Armstrong103 Increasingly, it has been positioned as a patient safety (‘harm’) issue,Reference Moriates100 stretching the concept of safety to include psychological harm as well as physical injury.Reference Lipitz-Snyderman and Korenstein104

3.5 Recognising Systemic Influences on Overuse

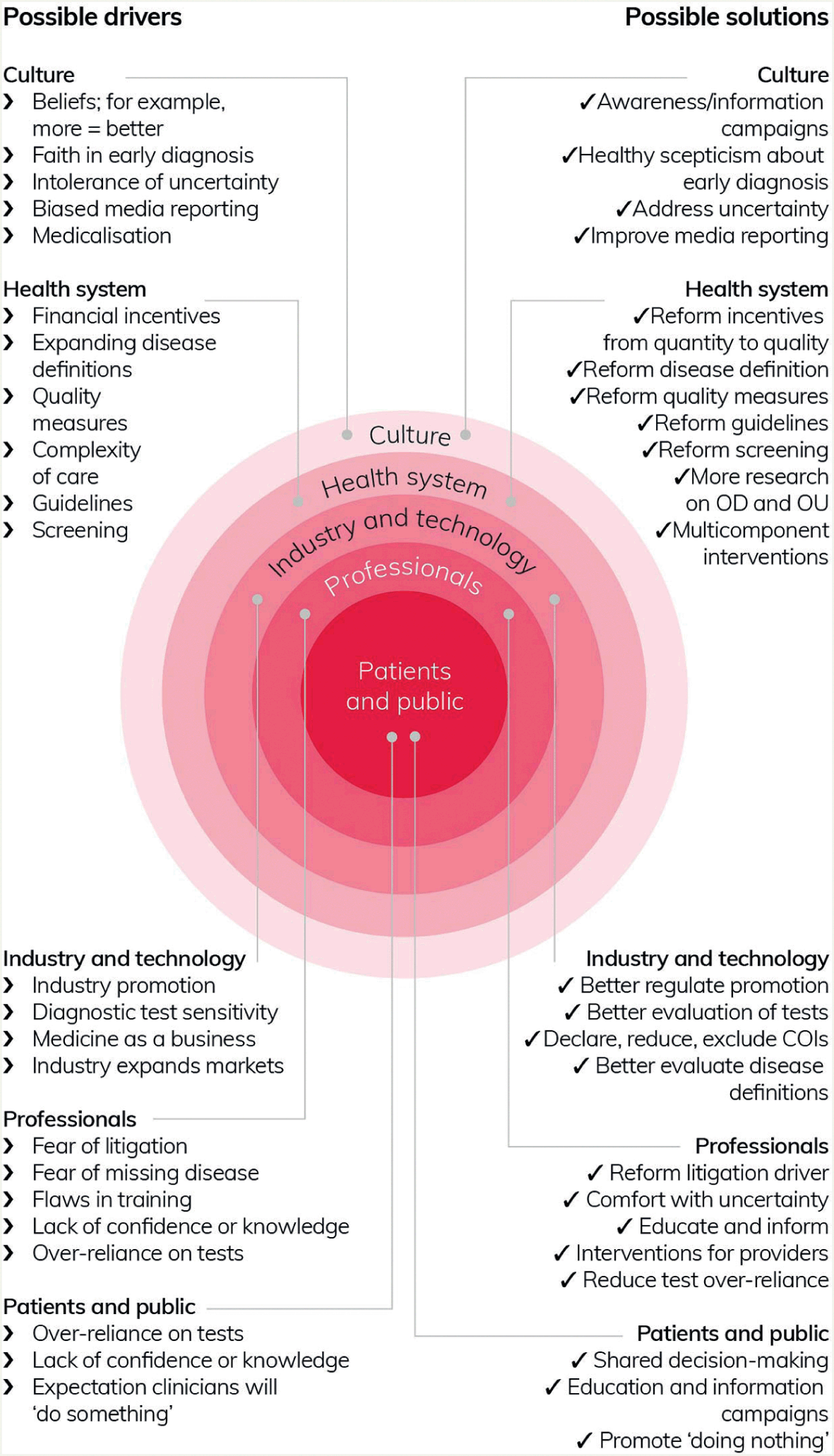

To address overuse as a systemic quality issue, it is necessary to have an appreciation of its systemic drivers (Figure 2). For example, efforts to address problems of underuse may unintentionally result in overuse.Reference Hicks98,Reference Pathirana, Clark and Moynihan105 Clinical guidelines provide a clear example: historically, they focused on what should be done rather than what should not be done (and in what circumstances).Reference Hicks98 Associated payment models and other (e.g. reputational) incentives have not always targeted the appropriate use of interventions, but they have influenced physicians’ recommendations and so may lead to a situation of oversupply.Reference Richardson and Peacock106 Less obvious systemic features, such as appointment structures that fail to allow enough time for thorough explanations of the benefits and harms of potential interventions, may also contribute to overuse. Other drivers relate to frontline interactions between professionals and patients (e.g. cultural beliefs that more is better,Reference Pathirana, Clark and Moynihan105,Reference Siemieniuk, Harris and Agoritsas107 defensive medicine, lack of recognition of the potential harms and limits of medical interventions), and market factors (e.g. industry-driven new technologies).Reference Pathirana, Clark and Moynihan105,Reference Siemieniuk, Harris and Agoritsas107 The widespread overuse of knee arthroscopy in conditions such as knee arthritis and meniscal tears provides an example of how various drivers converge to produce overuse. Its overuse has been attributed to patient expectations, financial incentives, and patients or clinicians erroneously attributing clinical improvements following surgery to the arthroscopy intervention, rather than to other factors.Reference Siemieniuk, Harris and Agoritsas107

Figure 2 Overdiagnosis and related overuse: mapping possible drivers to potential solutions

Even apparently individualised behaviours are shaped systemicallyReference Pathirana, Clark and Moynihan105 and are not simply the result of individual choices. For example, professionals’ fear of litigation is directly linked to the institutional systems through which they are monitored and held accountable. Clinicians may err on the side of caution, proceeding with interventions of unclear utility in an effort to fit in with local practice and customs and to help them defend themselves should questions be asked about their practice.Reference Armstrong and Hilton108 And a survey of US physicians found that respondents reported that colleagues were ‘more likely to perform unnecessary procedures when they profit from them’.Reference Lyu, Xu and Brotman109 Overuse may also become normalised and embedded in policies and guidelines over time due to oversupplyReference Mulley110 – with or without involvement of conflicts of interest that are known to distort healthcare research, strategy, expenditure, and practice.Reference Stamatakis, Weiler and Ioannidis111 Multiple and intersecting drivers arising from different parts of the healthcare system precipitate ethical questions about who is accountable for overuse and its prevention – for example, individual clinicians, healthcare managers, or politicians?

4 Efforts to Address Overuse

Efforts to address overuse come in many different shapes and sizes. It is not possible to cover all of these in detail but, in this section, we present an overview of the international literature using illustrative examples to demonstrate a selection of types of activities and some of the challenges involved. Many of our examples are drawn from the UK, with its distinctive health system characteristics. Interventions elsewhere have similarly been shaped by their own healthcare contexts, particularly the payment mechanisms involved and wider drivers of overuse that dominate the healthcare landscape.

4.1 Campaigns and Awareness-Raising Activities

Advocacy activity and campaigns increasingly target the problem of overuse, united by the goal of achieving widespread reduction in the use of ineffective or inappropriate interventions, based on established scientific evidence. This activity has drawn attention to a range of interventions, including tests, treatments, and processes of care that are argued to have questionable or no benefit and which should therefore be avoided or withdrawn.Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6,Reference Chan, Chang, Nassery, Chang and Segal20,Reference Elshaug, Watt, Mundy and Willis22,Reference Prasad, Vandross and Toomey112 Overuse campaigns include a series of special issues on ‘too much medicine’ in the British Medical Journal,Reference Moynihan and Smith113 and the international Preventing Overdiagnosis movement.Reference Moynihan, Doust and Henry9 National campaigns in Scotland (Realistic MedicineReference Fleck114) and Wales (Prudent HealthcareReference Aylward, Phillips and Howson16) have accompanied those based in England. Elsewhere, initiatives have included the Journal of the American Medical Association’s ‘less is more’ seriesReference Lipitz-Snyderman and Bach19 and The Lancet’s ‘right care’ series.Reference Saini, Brownlee, Elshaug, Glasziou and Heath4–Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6,Reference Saini, Garcia-Armesto and Klemperer92–Reference Elshaug, Rosenthal and Lavis95 Reports from influential healthcare organisations have also brought the topic to greater prominence.3

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign,115 which was established in 2012 and arose from work to improve performance of the US healthcare system, is a particularly important campaign internationally in highlighting the potential harms of overuse for patients. Choosing Wisely campaigns in the USA and elsewhere have centred on specific overused tests and interventions (see Box 3 for the UK implementation of the campaign,Reference NE, CH, TD, MB and Wisely75,Reference Scott and Duckett120 which is led by the Academy of Medical Royal CollegesReference Malhotra, Maughan and Ansell116). In most cases, targeting of these interventions is based on high-quality evidenceReference Horvath, Semlitsch and Jeitler121 and on prevalence data indicating significant opportunity to improve care and achieve better value for money.Reference Colla, Morden, Sequist, Schpero and Rosenthal122

The Choosing Wisely campaign has taken a bottom-up approach,Reference Ellen, Wilson and Vélez91 targeting clinicians, patients, and the public with the aim of ‘supporting conversations between physicians and patients about what care is truly necessary’.Reference Wolfson, Santa and Slass123 Patients have been positioned as consumers who can push back against the institutional forces that lead to overuse. In the USA, ABIM’s partnership with Consumer Reports (a non-profit consumer organisation) has led to considerable success in reaching into the public domain with educational messages relating to overuse.Reference Levinson, Kallewaard and Bhatia48,Reference Wolfson, Santa and Slass123 The campaign has simultaneously adapted its message to appeal to clinicians by framing overuse as a problem of waste as well as unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment.Reference Wolfson, Santa and Slass123

Box 3 Choosing Wisely and other UK campaigns

The UK’s Choosing Wisely campaignReference Malhotra, Maughan and Ansell116 has published a list of 40 overused interventions that patients and clinicians should question.Reference Torjesen117 It has also developed resources for patients and clinicians to support shared decision-making, such as ‘Four questions to ask my clinician or nurse to make better decisions together’, which uses the acronym BRAN:

What are the Benefits?

What are the Risks?

What are the Alternatives?

What if I do Nothing?

Other national initiatives that have sought to address overuse include Realistic Medicine (Scotland) and Prudent Healthcare (Wales). These national healthcare strategiesReference Fleck114,118 provide overarching principlesReference Fenning, Smith and Realistic Medicine119 around which a wide range of improvement activities (more or less geared to overuse) have been aligned. The principles emphasise that many patients prefer less intervention than they receive and stress the need for improved shared decision-making (see Box 5). As with the campaigns Choosing Wisely and Preventing Overdiagnosis, these UK-based national strategy ambitions have not always been subject to robust evaluation either prior to or alongside their implementation.

Studies of US commercial insurance claims data thus far have concluded that Choosing Wisely has had only a marginal impact on its targeted interventions.Reference Rosenberg, Agiro and Gottlieb124,Reference Hong, Ross-Degnan, Zhang and Wharam125 But Bhatia et al. suggest a broader ‘integrative framework’ approach to evaluating outcomes is needed, including clinical measures from electronic records alongside patient and physician experience surveys and patient-reported outcome measures.Reference Bhatia, Levinson and Shortt126 However, as Chalmers et al.Reference Chalmers, Badgery-Parker and Pearson51 have subsequently reported, the vast majority of recommendations from the Choosing Wisely lists are not measurable using routinely collected datasets, leading to considerable complexities in meaningfully measuring outcomes.

The international Preventing Overdiagnosis campaign has also provided a focus for clinicians and researchers committed to reducing the use of ineffective or harmful interventions. Like Choosing Wisely, its goals have been primarily around articulating and drawing attention to the problem and gaining support among clinicians. Since 2013, the campaign’s annual conference has highlighted the harms associated with early detection and the widening of disease definitions, thereby providing a counter-narrative to the dominant surveillance-focused narratives embedded in health policy.Reference Moynihan, Doust and Henry9 Such high-profile forums have been supported by ground-level movements such as the Royal College of General Practitioners’ overdiagnosis group,Reference McCartney and The127 which has provided day-to-day opportunities for general practitioners (GPs) and others to discuss the science and the practicalities around issues of overdiagnosis.

4.2 Tackling Overuse through Different Approaches to Care

Although the problem of overuse has been recognised in research and policy domains for several decades, until recently many efforts to tackle it have been relatively ‘passive’.Reference Parkinson, Sermet and Clement128–Reference Parker, Rappon and Berta130 These have included the publication of guidelines or educational materials,Reference Parker, Rappon and Berta130 health technology reassessment outputs such as NICE’s do-not-do lists,Reference MacKean, Noseworthy and Elshaug131,Reference Wammes, van den Akker-van Marle and Verkerk132 evolution in prescribing patterns,Reference Parkinson, Sermet and Clement128 and other evidence of a practice’s ineffectiveness or harm.Reference Niven, Mrklas and Holodinsky129 Some of these approaches have had a significant impact on practice.Reference Colla, Mainor, Hargreaves, Sequist and Morden133 But in this section we focus mainly on what some have described as ‘active strategies to change practices’.Reference Parker, Rappon and Berta130 These more active strategies go beyond awareness-raising, the dissemination of tools and guidelines, and educational or decision support. They involve the types of intervention that are commonly understood as quality improvement – usually incorporating defined mechanisms, theories of change, and outcome measures.

Verkerk et al. have argued that understanding the different types of low-value care is fundamental to tackling overuse effectively.Reference Verkerk, Tanke, Kool, van Dulmen and Westert21 They suggest (Figure 3) three broad approaches: ineffective care requires a ‘limit’ approach, inefficient care requires a ‘lean’ approach, and unwanted care requires a ‘listen’ approach. (For further details on Lean approaches to improving quality and safety in healthcare, see the Element on Lean and associated techniques for process improvement.Reference Radnor, Williams, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic134)

Figure 3 Typology of low-value care

Internationally, the majority of interventions targeting overuse have fallen into Verkerk’s ‘limit’ category, most commonly targeting medication use (56%), followed by radiology (12%), procedures (10%), and labs/pathology (10%).Reference Colla, Mainor, Hargreaves, Sequist and Morden133 Colla et al. found that most interventions were implemented in hospitals (56%), followed by ambulatory care settings (20%) and health systems (16%).Reference Colla, Mainor, Hargreaves, Sequist and Morden133 They identified a variety of both demand-side and supply-side interventions. On the demand side, interventions included patient cost-sharing (i.e. where the cost of healthcare services is divided between the patient and the insurance plan), patient education, and public reporting of provider performance. On the supply side were interventions such as pay-for-performance, insurer restrictions, risk-sharing agreements (which spread the financial and clinical risks from introducing a new drug between the pharmaceutical company and the health authorities), clinical decision support (see Box 4), clinician education, provider feedback, and interventions with multiple elements. Clinician decision-support interventions were most commonly applied in order to limit overuse and were also reported to be most effective.

Although decision-support interventions have been shown to be successful in many contexts, they may be complicated by factors such as difficulty in incorporating standardised protocols into individualised care, and difficulty anticipating the harms from potential interventions due to these occurring further downstream from the unnecessary intervention.Reference Lipitz-Snyderman and Korenstein104 Boxes 4–6 highlight some examples of successful interventions to address overuse, as well as the complexities of implementing such interventions that relate to applying evidence in real-world contexts.

Box 4 Initiatives to trigger patient or clinician reconsideration

Patient Education Initiative

The EMPOWER (Eliminating Medications through Patient OWnership of End Results) trial focused on evaluating the effectiveness of a direct-to-consumer educational intervention aimed at reducing benzodiazepine use in older adults in Canada,Reference Tannenbaum, Martin, Tamblyn, Benedetti and Ahmed135 and it demonstrates the value of patient involvement in interventions to reduce overuse. The intervention involved patient education about risks and harms of benzodiazepine use, peer champion narratives to support self-efficacy, and the specification of clear steps for reducing and replacing the medication. The intervention also encouraged people to initiate conversations with their doctor. The trial found that the intervention was effective in eliciting discussion and shared decision-making, resulting in significant levels of deprescribing and dose reduction.

Implementing an Approval Process before Knee Arthroscopy

Chen et al.’s Australian study involved a clinical governance process which required clinicians to seek approval from a senior clinician prior to referring a patient aged 50 years or older for knee arthroscopy.Reference Chen, Harris, Sutherland and Levesque136 Although there is strong evidence against undertaking this procedure, referral rates had remained high. Following the intervention, referral rates dropped (by almost 60% in one region), indicating that simple and low-resource policies can have a significant impact on clinician behaviours in some circumstances.

Box 5 Shared decision-making interventions

Shared decision-making is increasingly being positioned as a means to tackle overuse.Reference Pathirana, Clark and Moynihan105 A key element is the perceived potential to change the way decisions are framed by signalling that doing nothing or pursuing a strategy of active surveillance (rather than immediate intervention) can be discussed as a deliberate or positive action.Reference McCaffery, Jansen and Scherer137 By focusing on joint decisions between the patient and clinician, the approach involves both demand-side and supply-side elements.Reference Morgan, Leppin, Smith and Korenstein138

Shared decision-making has a prominent place in the UK’s Choosing Wisely campaign, alongside recommendations for clinicians of things not to do and questions for patients to ask of their clinicians (see Box 3). Shared decision-making is promoted as an effective strategy for tackling overdiagnosis and overtreatment, with Choosing Wisely citing what it sees as its positive influence on inappropriate antibiotic use in acute respiratory infections, for example.

One prominent example is the MAGIC (MAking Good decisions In Collaboration) programme, which ran between 2010 and 2013 as a knowledge translation project designed to test the implementation of shared decision-making in real-world clinical contexts.139 The programme was based on a large body of evidence showing the benefits of shared decision-making, including its potential impact on overuseReference Coulter140 – an evidence base that has since been extended.Reference Berwick5,Reference Stacey, Légaré and Lewis141 MAGIC highlighted various challenges to implementing shared decision-making in practice.Reference Joseph-Williams, Lloyd and Edwards142 These included factors relating to clinicians, patients, and healthcare organisations, summarised as: ‘We do it already’; ‘We don’t have the right tools’; ‘Patients don’t want shared decision-making’; ‘How can we measure it?’; and ‘We have too many other demands and priorities’. A particular problem in general practice was that processes for shared decision-making could come into conflict with financial incentives encouraging particular activities. The project also suffered from difficulties in developing meaningful outcome measures.

Box 6 Pharmacist roles for deprescribing in care homes

Some efforts to tackle medicines overuse as a system-wide problem have involved investment in new roles to review and optimise medicines use, as well as changes to the organisation and delivery of services. In the UK, these approaches have been used to address problematic polypharmacy, defined as use of multiple medications, where ‘the multiple medications are prescribed inappropriately, or where the intended benefit of the medication is not realised’.Reference Duerden, Avery and Payne143 It is associated with risk of harm from adverse drug reactions and other negative outcomes. For older people in particular, it is associated with increased risk of falls, hospital admission, and mortality.

Problematic polypharmacy results from a silo-based, as opposed to holistic, approach to care of people living with multimorbidity. The national NHS England Medicines Optimisation in Care Homes programmeReference England144 involves the creation of new pharmacist roles to support review and optimisation of medicines for older people in care homes. The focus is on reducing unnecessary medication in the context of multidisciplinary team-working across primary care and social care settings. Alves et al.’s 5-year evaluation of a pharmacy-led model of deprescribing – a team of primary care pharmacists supported GP practices in Somerset to undertake medication reviews and deprescribing in care homes – found it led to a wide range of pharmacist interventions to deprescribe medications that were deemed not to be needed, or where polypharmacy presented a safety risk. The programme also generated significant cost savings.Reference Alves, Green and James145

A challenge for system-wide approaches targeting deprescribing in care homes is that of overcoming some of the barriers to medication optimisation for this patient group. For older people with dementia and people approaching the end of life, decisions about optimising medication may be complicated by reduced decision-making capacity and difficulties with comprehension and communication. Involving relatives and carers may result in conflicting views, and establishing goals of care may be complex.Reference Reeve, Bell and Hilmer146 This highlights the tensions between organisational, regional, or national goals to reduce problematic polypharmacy and aspirations for shared decision-making at the point of care about what might be best for the individual. An example of an approach that aims to support shared decision-making about deprescribing in care home settings is the medication review project, funded by the Health Foundation and led by Northumbria Healthcare NHS Trust, which aimed to put care home residents and their relatives at the centre of the decision-making process.147

Some researchers have argued that interventions should focus more on ‘direct intervention by reimbursement policy makers’,Reference Parkinson, Sermet and Clement128 encouraging policy-makers involved in contract management to use payment systems (which may or may not have been driving overuse) as levers on clinical practice. However, changing payment systems alone is unlikely to address overuse without precipitating detrimental consequences. Increasingly, researchers have highlighted that multiple, interrelated factors drive overuse, and that interventions to address overuse should therefore reflect these multiple dimensions – which are specific to the particular healthcare context.

Colla et al.’s systematic review identifies that the approaches with the most potential to address low-value care are those that involve multicomponent interventions targeting both patients and clinicians.Reference Colla, Mainor, Hargreaves, Sequist and Morden133 The review also highlights clinical decision support and performance feedback as effective strategies with a sound evidence base. The authors recommend more extensive use and evaluation of multicomponent interventions. Their review also identifies problems and gaps in the research, including publication bias, a focus on volume reduction rather than value, dominance of acute sector interventions, and few studies that include more clinically meaningful measures, such as clinical appropriateness, patient-reported outcomes, or elicited patient preferences.Reference Colla, Mainor, Hargreaves, Sequist and Morden133,Reference Maratt, Kerr and Klamerus148

Overall, there is a paucity of good quality literature on interventions to address overuse in low-income and middle-income countries, with obvious implications for addressing urgent problems such as the inappropriate use of antibiotics.Reference Van Dijck, Vlieghe and Cox149 In all clinical and geographical contexts, it is important to recognise that, as shown in Figure 2, complex social factors (e.g. antibiotics as a quick fix within a resource-stretched healthcare systemReference Willis and Chandler97) complicate simple concepts of getting evidence into practice. (See the Element on implementation science for a broader discussion.Reference Wilson, Implementation science, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic150)

5 Critiques of Approaches to Addressing Overuse

The analysis presented so far in this Element has emphasised the pressing importance of work to address overuse, both to avoid patient harm and to ensure limited healthcare resources are used wisely, particularly as it is likely that many reports have underestimated the scale of the problem and the diverse harms. Approaches to addressing overuse have taken a variety of forms, often targeting the behaviour of clinicians in order to prevent inappropriate care, or promoting shared decision-making in anticipation that this will reduce patient demand for interventions. We have highlighted the growing body of evidence about the effectiveness of approaches to address overuse, which points to the value of multicomponent interventions.

In Section 5.1, we present some prominent critiques that support advances towards greater system-level intervention. Then in Section 5.2, we discuss an alternative and opposing critique that highlights the potential impact of such authoritative policy programmes on stakeholders, importantly frontline clinicians and patients. We highlight that the enthusiasm for the avoidance of harm associated with overuse and for wise use of resources may not always carry over into support for more restrictive approaches that remove (apparently) valid options. In drawing attention to this opposing critique, our aim is not to undermine the importance of finding effective approaches to addressing overuse (all interventions and policies inevitably bring about their own winners and losers); rather, we hope that by highlighting such tensions, we can bring to the fore important social elements of intervention development that may be overlooked – sometimes to the detriment of their success. These critiques prompt our own final reflections on the topic in Section 6.

5.1 Moving towards System-Level Healthcare Improvement

As we noted in Section 3, researchers have increasingly drawn attention to the need to systematically identify and address overuse across whole healthcare systems.Reference Nassery, Segal, Chang and Bridges2,Reference Chan, Chang, Nassery, Chang and Segal20,Reference Segal, Bridges and Chang50,Reference Oakes, Chang and Segal151 Although some impact can be achieved by withdrawing interventions completely from approved treatment protocols, this is appropriate for a minority of interventions only; many interventions may be appropriate in some, but not other, circumstances. In addition, experts have observed that a greater burden of proof is generally required to remove interventions from established guidelines and protocols than it is to incorporate them in the first place.Reference King152

Nassery et al. propose that creating an index of overused services (similar to a stock market portfolio) would enable policy-makers to identify and address the structural problems that generate overuse. They suggest that such an approach would facilitate a shift from addressing overuse in a ‘piecemeal’ fashion (i.e. individual clinical topics identified and addressed in isolation) to addressing it as ‘a widespread and pervasive phenomenon’.Reference Nassery, Segal, Chang and Bridges2 But, as we have seen, the evidence base is skewed towards particular areas of medicine, with more studies in curative medicine, for example, than in rehabilitative care, health promotion, or nursing practice.Reference Verkerk, Huisman-de Waal and Vermeulen27,Reference de Vries, Struijs, Heijink, Hendrikx and Baan153 In order to enable more informed prioritisation at a system level, more diversity of studies is required, as is greater transparency about the quality and scope of the available evidence.Reference de Vries, Struijs, Heijink, Hendrikx and Baan153

Some have advocated more broadly for multicomponent interventionsReference Colla, Mainor, Hargreaves, Sequist and Morden133 that are carefully integrated into clinical care pathways and include ‘policy changes and/or changes to funding models’ as these are ‘predicted to have the greatest likelihood of facilitating de-adoption’.Reference Niven, Mrklas and Holodinsky129 However, better understanding of the drivers of overuse (involving multiple organisational processes as well as individual behaviours) are needed for this kind of system-level action. And as Harvey and McInnes have noted: ‘… the reasons why healthcare professionals continue with practices for which there is little or no supporting evidence are typically complex and include a combination of individual (eg, beliefs about evidence, past experience), interprofessional (eg, influence of peers), and contextual (eg, economic, industry and marketing influences) factors’.Reference Harvey and McInnes154

Hensher et al. similarly have drawn on various economic perspectives (health, behavioural, ecological) to highlight the intersecting individual and system drivers of overuse, the dynamics of which will be different in different healthcare contexts; they note also the complexity of addressing these.Reference Hensher, Tisdell and Zimitat18 However, perhaps as a result of this complexity, system-level dimensions of overuse have consistently been overlooked within approaches to addressing overuse (see Box 7), with the problem often ‘misconstrued as … arising from both physicians’ integrity and autonomy rather than arising from system failures’.Reference Keyhani and Siu30

Box 7 The politics of system-level intervention in the UK

Policy-makers have sometimes been reluctant to address overuse overtly. In the UK, for example, local commissioning organisations have tended to allow overused interventions to ‘“wither on the vine” through lack of use’ (as replacement practices evolve, for example), or be discreetly removed or reconfigured during organisational mergers and takeovers.Reference Williams, Harlock and Robert62

More deliberate action to identify and address overuse has generally focused on broader disinvestment for the purpose of cost savings. But due to considerable political sensitivities, local policy-makers have often wanted to keep this work under the public radar to avoid raising concerns about rationing.Reference Schang, Morton, DaSilva and Bevan44,Reference Williams, Harlock and Robert62,Reference Williams, Robinson and Dickinson155 Such sensitivities may account for researchers reporting ‘little evidence of any tools or frameworks to support disinvestment decision-making’ in commissioning organisations,Reference Hollingworth, Rooshenas and Busby156 with interventions typically being small-scale and based on comparisons of local data with other commissioning regions.Reference Hollingworth, Rooshenas and Busby156,Reference Wye, Brangan and Cameron157

While financial levers are clearly important (e.g. financial incentives for patients and/or rewards or penalties for clinicians, clinics, and hospitalsReference Elshaug, Rosenthal and Lavis95), quality improvement approaches158 – with their attention to healthcare systems and mechanisms of intervention – are likely also to be important in taking forward work to address overuse. Despite the potential, Chassin lamented in 2013 that overuse has been ‘almost entirely left out of the quality improvement discourse’,Reference Chassin159 and it would seem that not much has changed since then. Publications such as The Lancet’s ‘right care’ seriesReference Saini, Brownlee, Elshaug, Glasziou and Heath4-Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust6,Reference Saini, Garcia-Armesto and Klemperer92–Reference Elshaug, Rosenthal and Lavis95 have highlighted overuse as a quality issue, but there are still relatively few examples of interventional studies that aim to address overuse with fully specified theories of change and outcome measures. Indeed, a 2018 review by Parker et al. identified only a small proportion of studies that outlined theoretical mechanisms of de-adoption;Reference Parker, Shahid and Berta160 and most of those employed psychological theories or behavioural science approaches (e.g. ‘nudge interventions’Reference O’Keeffe, Traeger and Hoffmann161) targeting frontline behaviours rather than more systemic reasons for overuse.

5.2 Tensions between Interventions to Tackle Overuse and Individualised Care

While systematic approaches may have a role in addressing structural factors in overuse, some aspects of them are increasingly being challenged by clinicians and patients. Evidence from across a diverse literature indicates that, in practice, it is difficult to develop consensus among stakeholders about what should be classified as overuse.Reference Scott and Duckett120 Systems and processes put in place to reduce the use of existing interventions inevitably have consequences for stakeholders, who may, as discussed earlier, have different understandings of what is valuable. As a result, efforts to standardise definitions of overuse (what is, or is not, appropriate for particular groups of patients), and then to enforce compliance, may not be accepted by professionals or patientsReference Levinson, Kallewaard and Bhatia48,Reference Owen-Smith, Coast and Donovan162–Reference W, L and J164 (see Box 8).

Box 8 The Evidence-Based Interventions programme

In England, the Evidence-Based Interventions (EBI) programme, which was established in 2018, aims to ‘reduce the number of inappropriate interventions provided on the NHS’.Reference England165 The programme represents a shift in approach from engagement exercises (e.g. Choosing Wisely) and strategic principles (e.g. Prudent Healthcare) to more targeted (‘active’) initiatives that are integrated into payment systems.Reference Parkinson, Sermet and Clement128 Guidance has been issued to clinical commissioning groups166 – which are organisations that commission primary care services in England – mandating them to restrict interventions listed as inappropriate, including through the use of financial levers to ensure compliance. An initial list of 17 interventions that ‘should not be routinely commissioned’ (e.g. dilatation and curettage [D&C] for heavy menstrual bleeding) or ‘should only be commissioned or performed when specific criteria are met’ (e.g. knee arthroscopy for patients with osteoarthritis) was intended to be expanded over time.167 There is accompanying guidance on items that should no longer be routinely prescribed in primary care.168

Although the programme has emphasised that its main objective is clinical improvement (and any associated savings will be reinvested in patient care169), critics have argued that it is geared towards delivering cost savings.Reference Puntis170 Its guidance has been challenged by commentators, clinicians, and patients. Specific criticisms relate to the evidence base for restriction (including blanket restriction of some interventions, which is not in line with NICE clinical guidelines or the best interests of patients), the resources required to explain these restrictions in clinical practice, and the consequences for clinician–patient relationships.Reference Puntis170–172 Debates highlight the tensions between different approaches to determining and measuring value (see work by Chalmers et al.,Reference Chalmers, Badgery-Parker and Pearson51 Pandya,Reference Pandya173 and Tsevat and MoriatesReference Tsevat and Moriates174).

The EBI programme provides an example of how de-implementation (e.g. restricting existing services) may involve fundamentally different challenges from implementation. Disinvestment initiatives such as this, even when based on an apparently relatively strong evidence base, are likely to be contested when applied to frontline clinical practice. Resistance has been particularly strong where attempts to reduce overuse are integrated into broader cost-savings work; policy-makers face charges of ‘rationing’ – ‘the denial of health care that is beneficial but is deemed to be too costly’.Reference Bevan and Brown175 This notion has become highly emotive and political, making policy-makers nervous about how disinvestment work will be perceived. Despite attempts to emphasise the quality improvement angle of decommissioning ineffective or harmful interventions, the distinction between addressing overuse and generating cost savings has been difficult to achieve in local policy-making.Reference Rooshenas, Owen-Smith and Hollingworth176

Resistance from clinicians and patients arises from ongoing tensions between their autonomy (clinical decision-making) and the imposition of standardised rules to address overuse which restricts that autonomy. Contributing to such tensions is the difficulty in applying traditional instruments for changing practice, which display a ‘[weak] ability to discriminate between inappropriate and appropriate care’.Reference Hensher, Tisdell and Zimitat18 Indeed, there are significant problems with applying average estimates of effects from the populations of clinical trials to individual patients for whom some benefit may exist.Reference Garner and Littlejohns33 Some treatments and conditions may also be soft targets for restriction, due to a lack of evidence or lobbying muscle from patient groups and social judgements about their value (e.g. cosmetic surgery, orthodontics).Reference Garner and Littlejohns33 Restrictive policies have the potential to lead to significant inequity between people who have what could be considered high-status conditions (i.e. well-recognised with strong research funding) or the social resources to self-advocate, and people who are not in this position (see Box 9).

Box 9 Independent Funding Request processes

Independent Funding Request (IFR) processes, which have been put in place as a mechanism for determining exceptionality alongside restrictive policies, have raised concerns about equity – with, for example, some patients apparently swaying decisions by harnessing considerable public and pharmaceutical company support in their appeals for expensive cancer drugs.Reference Ford177 IFR processes involve judgements about who is deserving of a restricted treatment and invite a huge amount of work from both patients and clinicians in making a case for treatment.Reference Russell, Swinglehurst and Greenhalgh178,Reference Russell and Being179 Due to the inherent problems of implementing IFRs, Heale and SyrettReference Heale and Challenging180 have gone as far as claiming that the IFR process is ‘unfair, unacceptable, and probably unlawful’. Other work suggests that targeting the overuse of low-value care in too broad and inflexible a manner may also result in the underuse of high-value care by some groups.Reference Bhatia, Levinson and Shortt126

Ellen et al. have argued that ‘a comprehensive approach [to overuse] likely lies in synergistic efforts between stakeholders and governments to identify overuse and subsequently undertake collaborative efforts to address it’.Reference Ellen, Wilson and Vélez91 Such efforts should take account of multiple dimensions of quality, including those relating to patients, physicians, and organisations and systems, and might be able to harness the support of those campaigning against overuse. However, as Hodgetts et al.Reference Hodgetts, Elshaug and Hiller181 found in their study of participatory decision-making about assisted reproductive technologies, such processes are labour-intensive and (politically) sensitive as they ‘involve the negotiation of different orders of evidence (empirical, contextual, and anecdotal), indicating a need for higher level discussion around “what counts and how to count it” when making disinvestment decisions’.

Crucially, patient experiences and patient and public priorities have been largely left out of interventional studies to address overuse systematically:Reference Colla, Mainor, Hargreaves, Sequist and Morden133,Reference Entwistle, Calnan and Dieppe182 this has meant that harms of overuse (and consequences of restrictive interventions) may be much more extensive than commonly reported, and underlying questions of value may sometimes only emerge during the translation of evidence into policy-making and clinical practice.Reference Entwistle, Calnan and Dieppe182 Although in theory patient perspectives are central to concepts such as value-based healthcare,Reference Tsevat and Moriates174 in practice these concepts are almost entirely economically focused and tend to be derived from the US healthcare context. The lack of focus on patients has led to increasing calls for overuse to be addressed within existing structures for patient safety.Reference Moriates100 Lipitz-Snyderman and Korenstein argue that this has various advantages – in particular, ‘framing overuse through the lens of patient safety’ provides the issue with an ‘institutional home’ and helps to highlight overuse ‘as an issue that affects clinical outcomes that are most important to patients and clinicians’.Reference Lipitz-Snyderman and Korenstein104 However, greater social science analysis is needed to understand overuse, value, and restrictive practices from alternative (particularly under-represented patient) standpoints.Reference Cupit and Armstrong183

6 Conclusions

In this Element we have highlighted how the term overuse can include a range of related concepts and that these have been variously employed across research, policy-making, and clinical practice. Concerns about overuse are present across a wide variety of healthcare contexts, and we have drawn on diverse examples to demonstrate this. But we have also noted that studies tend to be skewed towards particular areas of medicine, with a larger number of studies in curative medicine rather than in areas such as rehabilitative care, health promotion, or nursing practice.

As we have shown, much work on overuse has been focused on its identification, as this is a logical first step in the process of addressing it. But identifying overuse is not straightforward. We have drawn attention to some of the key challenges involved, particularly around how evidence of overuse is produced and used, and different stakeholder understandings of value. And we have highlighted that producing good evidence around overuse rates is often challenging. Ideas about what constitutes overuse are always shaped by social systems, and views about the possible benefits and potential harms of any particular intervention – and the most appropriate balance between these – may be challenged by those involved. These challenges apply both to efforts to identify particular instances of overuse and efforts to identify and address the problem at healthcare system level.

We have outlined the recent shift to addressing overuse as a new quality frontier, but we have also highlighted how overuse has long been understood, if somewhat neglected, as a form of inappropriate care (alongside underuse and misuse). We have considered increasing calls for overuse to be addressed more systematically, often involving policy-makers and changes to payment systems, but we have also discussed critiques that draw attention to the tension between standardised restrictive policies and individualised clinical care (and the complex social structures involved). Through case studies of efforts to address overuse in various forms, we have demonstrated some of the challenges involved in doing so.

Our discussion has drawn attention to how lack of conceptual clarity around overuseReference Hofmann184 produces practical tensions – in particular, an overarching tension between frontline and management (or financial) understandings of overuse. We observe that tensions – between frontline-clinical and managerial logics of overuse – relates to both identifying and addressing overuse, and we suggest it is likely to be exacerbated as researchers and policy-makers call for more systemic (standardised and incentivised) approaches. Such a challenge is likely to present differently across different healthcare systems.

The issues we have covered, and our reflections on some of the challenges, suggest a number of directions that further work on overuse could usefully take. First is the need for greater transparency about the quality and scope of the evidence available on overuse. In particular, greater diversity and quality of studies across different healthcare contexts would enable more informed prioritisation at a system level. The development of improved methodologies to identify interventions that have little benefit for patients would be helpful in more clearly establishing the scale of the problem.

Second, many of the interventions seeking to address overuse described in the literature are specific to the healthcare context in which they were situated (most are US-basedReference Tannenbaum, Martin, Tamblyn, Benedetti and Ahmed135). The drivers and dynamics of overuse are likely to be different across healthcare systems. For example, guidelines, performance measures, and governance processes may incentivise (over)use, as clinicians’ work is often orientated to these in the face of uncertainty; these will be context specific.Reference Cupit, Rankin, Armstrong and Martin185 Work is needed to draw out and understand the particular influences at play in different contexts, and how these influences are exerted, in order to inform decisions about whether strategies that seem to have been successful in one context will translate to another. The role of financial and reputational incentives should be a particular focus for research and intervention in fee-for-service systems.

Third, tensions between different concepts of quality and value among stakeholders should be recognised. Research should include (and prioritise) meaningful clinical measures relating to appropriateness and other outcomes that are important to patients.Reference Maratt, Kerr and Klamerus148 Although there will always be diverse opinions and priorities, and financial resources will always be limited, recognising the political dimensions of overuse might provide a welcome contribution to informed public discussion.

Finally, insights from healthcare improvement research are likely to be valuable in developing successful efforts to address overuse. These include the need to clearly articulate the problem and the factors driving it, as well as the need to recognise that these may vary in different cases – for example, according to features of the particular clinical context, or the professional or patient groups concerned. Also needed is careful, theory-informed design of interventions with clearly articulated and credible proposed mechanisms through which the desired outcomes will be achieved – along with robust evaluation of efforts to tackle the problem, including qualitative process evaluations capable of producing in-depth and nuanced accounts of whether and how interventions have worked in practice. There is a particular need for social science studies that can establish how concepts of overuse are being developed and employed in practice and the (unintended) consequences.Reference Armstrong103

In conclusion, overuse is a significant issue for the quality, safety, and cost of healthcare, particularly in countries where financial and other drivers exert a significant influence on the use of medical services. Addressing the overuse of medicine is a pressing global priority, and understanding the complexities involved is critical to informing new approaches to tackle it.

7 Further Reading

Articles

Chassin and GalvinReference Chassin8 – sets out the background to work on addressing overuse.

Pathirana et al.Reference Pathirana, Clark and Moynihan105 – an analysis of the drivers of overuse and related solutions.

Journal Series

The Lancet’s right care series: www.thelancet.com/series/right-care.

BMJ’s too much medicine series: www.bmj.com/specialties/too-much-medicine.

JAMA’s less is more series: https://jamanetwork.com/collections/44045/less-is-more.

Natalie Armstrong initially conceptualised and planned the Element, with input from Caroline Cupit and Carolyn Tarrant. Caroline Cupit wrote the first draft under Natalie Armstrong’s supervision, with contributions from Natalie Armstrong and Carolyn Tarrant. All authors contributed to revising the Element in response to reviewer feedback. All authors have approved the final version.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank the peer reviewers for their insightful comments and recommendations to improve the Element. A list of peer reviewers is published at www.cambridge.org/IQ-peer-reviewers.

Funding

This Element was funded by THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute, www.thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk). THIS Institute is strengthening the evidence base for improving the quality and safety of healthcare. THIS Institute is supported by a grant to the University of Cambridge from the Health Foundation – an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and healthcare for people in the UK.

Natalie Armstrong is supported by a Health Foundation Improvement Science Fellowship. Natalie Armstrong and Carolyn Tarrant are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC EM). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. Caroline Cupit is supported by a Mildred Blaxter Fellowship from the Foundation for the Sociology of Health and Illness.

About the Authors

Caroline Cupit is a social scientist, working at the University of Leicester and the University of Oxford. She uses sociological theory and methods and has particular expertise in institutional ethnography – an approach she employs to identify good care practices as well as systems and processes for improvement.

Carolyn Tarrant is Professor of Health Services Research and leads the Social Science Applied to Healthcare Improvement Research (SAPPHIRE) Group at the University of Leicester. She is a social scientist with expertise in qualitative methods, including ethnographic methods in applied healthcare research.

Natalie Armstrong is Professor of Healthcare Improvement Research at the University of Leicester and Health Foundation Improvement Science Fellow. A medical sociologist by background, her work uses sociological ideas and methods to understand health and illness and to tackle problems in the delivery of high-quality healthcare.

The online version of this work is published under a Creative Commons licence called CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0). It means that you’re free to reuse this work. In fact, we encourage it. We just ask that you acknowledge THIS Institute as the creator, you don’t distribute a modified version without our permission, and you don’t sell it or use it for any activity that generates revenue without our permission. Ultimately, we want our work to have impact. So if you’ve got a use in mind but you’re not sure it’s allowed, just ask us at enquiries@thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk.

The printed version is subject to statutory exceptions and to the provisions of relevant licensing agreements, so you will need written permission from Cambridge University Press to reproduce any part of it.

All versions of this work may contain content reproduced under licence from third parties. You must obtain permission to reproduce this content from these third parties directly.

Editors-in-Chief

Mary Dixon-Woods

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Mary is Director of THIS Institute and is the Health Foundation Professor of Healthcare Improvement Studies in the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the University of Cambridge. Mary leads a programme of research focused on healthcare improvement, healthcare ethics, and methodological innovation in studying healthcare.

Graham Martin

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Graham is Director of Research at THIS Institute, leading applied research programmes and contributing to the institute’s strategy and development. His research interests are in the organisation and delivery of healthcare, and particularly the role of professionals, managers, and patients and the public in efforts at organisational change.

Executive Editor

Katrina Brown

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Katrina is Communications Manager at THIS Institute, providing editorial expertise to maximise the impact of THIS Institute’s research findings. She managed the project to produce the series.

Editorial Team

Sonja Marjanovic

RAND Europe