1 Institutions and Political Legitimacy, a Debate

Armed humanitarian interventions have emerged as one of the most significant developments in global affairs since the end of the Cold War. These uses of military force, primarily led by democratic countries, pose fundamental questions about how the international community should respond to the worst human atrocities while preserving the principle of state sovereignty. More than that, they also shape and challenge our understanding of the role of liberal values in the international system.Footnote 1

One of the most striking features of humanitarian interventions is their association with multilateral, international institutions.Footnote 2 Indeed, political scientist Martha Finnemore argued that since World War II, “to be legitimate, humanitarian interventions must be multilateral.”Footnote 3 Yet, the precise role these institutions play in legitimizing such actions remains controversial.Footnote 4 United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Anan captured this controversy when he articulated the difficult tension facing the UN framework:

If, in those dark days and hours leading up to the [Rwandan] genocide, a coalition of States had been prepared to act in defense of the Tutsi population, but did not receive prompt Council authorization, should such a coalition have stood aside and allowed the horror to unfold?

To those for whom the Kosovo action heralded a new era when States and groups of States can take military action outside the established mechanisms for enforcing international law, one might ask: Is there not a danger of such interventions undermining the imperfect, yet resilient, security system created after the Second World War, and of setting dangerous precedents for future interventions without a clear criterion to decide who might invoke these precedents, and in what circumstances?Footnote 5

The Security Council, the only institution with the authority to legalize humanitarian intervention, is prone to gridlock. While it is designed to be cautious in authorizing military force and prioritize preventing disputes among the great powers, such a framework could produce severe human costs during a rapidly unfolding humanitarian crisis. On the other hand, turning to alternative multilateral processes, such as NATO’s role in the Kosovo crisis, or resorting to unilateralism, poses its own challenges. These alternative approaches risk undermining the existing international regime built to safeguard global peace and security and state sovereignty. Moreover, individual governments must also navigate the delicate balance of avoiding domestic and international backlash for conducting foreign policy seen as illegitimate,Footnote 6 while simultaneously managing the constraints multilateral institutions impose on their foreign policy autonomy.

These political and human stakes have sparked ongoing debate among policymakers and within public discourse. They also motivate a major body of scholarship on how international institutions influence the political legitimacy of foreign policies, including humanitarian intervention.Footnote 7 In fact, since Claude Inis observed that the United Nations could generate “legitimacy,” scholars have spent decades unpacking what that truly means.Footnote 8 Given Realist theory’s strong presumption that institutions have little impact on international security and war, researchers have grappled with why these seemingly powerless bodies hold any significance. Why does international support for a country’s foreign policy grow when such a policy receives institutional approval? If institutions do matter, which ones can bestow legitimacy, and why?Footnote 9

At least three lines of research address these questions. First, Constructivist scholars argue that an institution’s power to legitimize comes from its ability to shape beliefs about what behavior is appropriate and what ought to be followed. When a policy, such as military intervention, receives institutional legitimacy, it gains wider acceptance and support. Endorsements from multilateral institutions, for example, can reveal broad, international approval and that the purpose of intervention is not merely self-serving.Footnote 10 These institutions could also confer legitimacy by producing favorable and fair outcomes and by following appropriate procedures.Footnote 11 Conversely, the absence of institutional backing can also delegitimize a country’s foreign policy.Footnote 12 These pathways to legitimacy are rooted in the social interactions between political actors and institutions.

A second line of research argues that institutions legitimize the use of armed force by legalizing it.Footnote 13 People may be more inclined to support legally sanctioned actions due to their intrinsic respect for the rule of law in the international system.Footnote 14 Legality can also hold practical value. For instance, adhering to international law helps safeguard a country’s reputation.Footnote 15 From this perspective, because the Security Council holds the exclusive authority under the current international legal system to authorize military action outside of self-defense,Footnote 16 it should have a unique ability to legitimize uses of armed force, including humanitarian interventions.

A third line of research recasts the concept of legitimization in rational, game-theoretic terms, leading to what is broadly known as rational information transmission theories. One study posits that the Security Council’s endorsements act as signals that reassure observers about the potential for military force to provoke great power conflict and destabilize the international system.Footnote 17 A subsequent body of research emphasizes how institutions can convey information that shifts public perceptions about the motives behind war and its potential material cost and benefits.Footnote 18 To explain why institutions can send such signals, these theories focus on institutional characteristics such as independence (neutrality) and conservativeness.Footnote 19 Independent institutions include a diverse range of veto players, and conservative institutions set a high bar for policy approval. Overall, these arguments generally suggest that policy endorsements by the Security Council are influential because they represent an elite pact, a diverse group of countries, and a significant barrier to authorizing military action.

This arc of scholarship has profoundly influenced international relations theory. It has taken the field from a general skepticism about the relevance of international institutions to what is now the conventional wisdom: the Security Council and other institutions enable governments to reassure, signal, and ultimately persuade skeptical audiences, including the mass public and foreign elites, about the legality and merits of their foreign policy.Footnote 20

However, some puzzling cases and recent research highlight the need for additional theorizing and empirical investigation to better grasp these institutional dynamics. For instance, the historical record includes cases where international institutions other than the Security Council conferred legitimacy. In 1999, the United States and NATO allies conducted an armed humanitarian intervention in Kosovo without Security Council approval. But rather than condemning the United States, much of the international community declared that the illegal intervention was nevertheless legitimate.Footnote 21 Even several non-Western members of the Security Council refrained from condemning the intervention.Footnote 22 Theories focusing on international law struggle to explain these events. Similarly, existing information models emphasizing institutional traits like independence and neutrality fall short of explaining NATO’s apparent ability to legitimize intervention. After all, NATO is often seen as a homogenous body with a reputation for aligning with U.S. interests.

Recent experimental research also reveals intriguing patterns existing theories cannot fully explain. One study found that governments can raise support for their policies among foreign public simply by seeking Security Council approval, even if that approval is ultimately denied due to opposition from some of the permanent (P5) council members.Footnote 23 This finding suggests that neither legality nor an explicit endorsement from the great powers is required for an institution to have influence. It also underscores public skepticism of the Security Council’s procedural element, particularly the P5’s “veto” power. Meanwhile, existing studies show that institutional approval does not necessarily lead people to reassess their beliefs about the material costs and benefits of war,Footnote 24 and that IOs other than the Security Council can rally support for war in ways that existing models cannot account for.Footnote 25 In sum, while current research demonstrates the ability of international institutions to influence politics by shaping domestic and international opinion, there is a clear theoretical gap in understanding why this influence exists and which institutions can wield it.

1.1 Interpreting Legitimization as a Social Cue

This Element develops a new theory to understand how international institutions shape the perceived legitimacy of foreign policy. It advances a social theory of legitimacy that builds upon political psychology, social identity theory, as well as insights about state-level norms from constructivist literature. It begins with the premise that legitimacy is in the eye of the beholder, so to theorize and uncover evidence about it, one must first begin with the audience of legitimacy: individuals.

To preview, Section 2 elucidates the social cue theory in two main parts. It first explains how social cues work in general terms to lay down the theory’s underlying logic, allowing researchers to apply it to other phenomena. It then develops the theory in the specific context of humanitarian intervention by the community of liberal democracies. Generally stated, the theory interprets legitimization as a social process driven by identity. It argues that institutions, depending on the identities they represent, confer legitimacy by sending social cues about whether a policy is socially appropriate and how a specific group of countries will receive it. These cues operate through relational mechanisms, alleviating concerns about norm abidance, group participation, as well as status and image, and by exerting direct social pressure on group members to conform. Additionally, the theory explains how individuals and communities of ingroup members both can send social cues, but that those cues are more influential when channeled through institutions. When an institution represents a social group, it can amplify and clarify the social meaning of a cue, enhancing its legitimizing effect.

By analyzing institutional legitimization in terms of identity politics, the social cue theory produces a new set of propositions regarding whose cues matter and why. Cues from ingroup members or institutions should matter most because they exert social pressure and induce social considerations regarding a policy. In the case of humanitarian interventions, the relevant ingroup is the community of liberal democracies, which are the main actors behind these interventions, and its closely linked institution, NATO. The theory implies that liberal democracies vis-à-vis NATO can send social cues to influence how domestic and foreign community members perceive humanitarian intervention. This phenomenon occurs because these audiences view NATO as an international organization (IO)Footnote 26 representing their ingroup.Footnote 27 In contrast, cues from outgroup countries and institutions representing a more diffuse community like the Security Council exert less social influence, particularly when an ingroup cue already exists. Section 2 concludes with a discussion of alternative explanations (regarding material considerations and Western regionalism), scope conditions (relating to policy domain, temporality, and political actors), and how the social cue theory is distinct from existing informational arguments.

Sections 3–5 test the social cue theory’s implications through a multi-method research design, using historical polls, case studies of U.S. intervention, news media analysis, a survey of policymakers in the United Kingdom, and nine public opinion surveys and survey experiments conducted in the United States, Japan, and Egypt. The findings from these studies support the social cue theory while refuting alternative explanations.

To begin, during humanitarian interventions, both the Security Council and NATO are highly visible to citizens in liberal democracies – appearing in news articles, speeches, and media broadcasts. As a result, their policy positions become key social cues to the public.

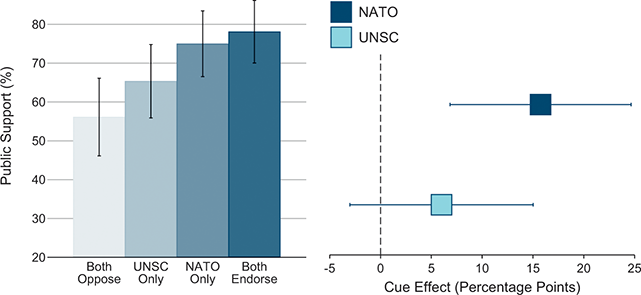

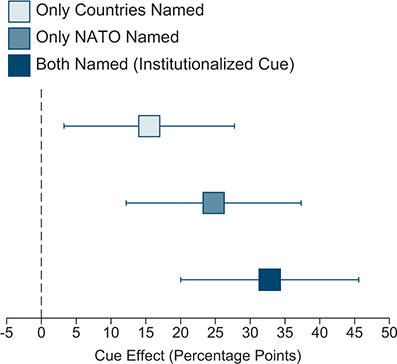

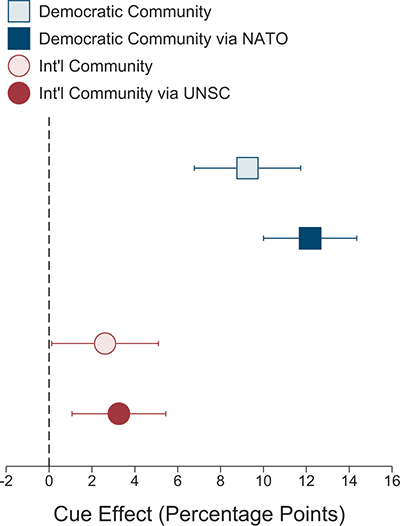

Next, the historical record of U.S. intervention and original survey experiments reveal that ingroup cues significantly influence domestic public opinion. Americans tend to be skeptical of interventions without institutional backing, such as in the case of Rwanda and Syria. They are more enthusiastic about intervention when formal institutional backing is involved but express little distinction between NATO’s sole approval versus both NATO and the Security Council’s backing. Thus, the historical data suggest that ingroup cues from NATO and the liberal community raise domestic public approval, while the Security Council’s additional endorsement has minimal impact. Moreover, survey experiments demonstrate the causality found in the historical record. NATO’s policy endorsements cause an increase in public support for intervention. Furthermore, once an ingroup cue from NATO is sent, the Security Council does little to shift public opinion. The reverse, however, is not true. Even with a Security Council endorsement, NATO’s additional endorsement still increases public approval. Lastly, the experiments also show that social cues from the liberal community influence public opinion, but its cues exert an even stronger influence when conveyed through NATO, demonstrating the power of institutionalized social cues.

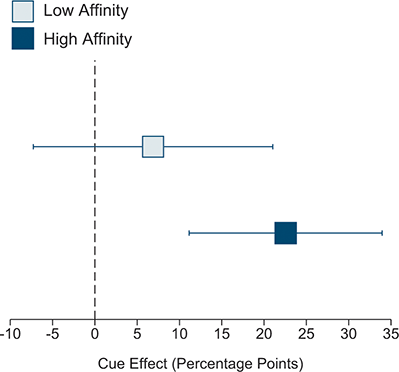

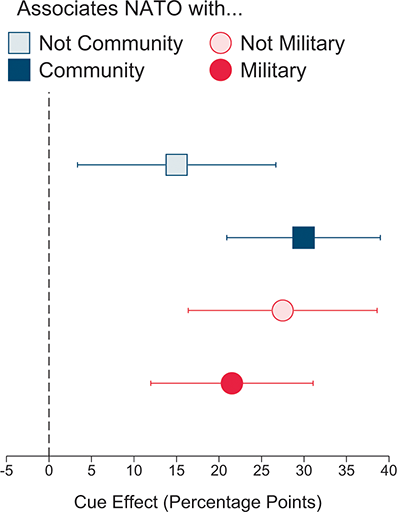

Three additional empirical results demonstrate the social cue theory’s causal processes while ruling out alternative explanations relating to military and material burden-sharing capacity. First, NATO’s influence is most substantial among individuals who associate NATO with the liberal community and who express affinity with its member countries, rather than those who associate NATO solely with military strength. Second, NATO’s impact on public opinion operates through the theorized relational mechanisms: concerns about norm abidance, group participation, and status and image. Third, even after removing its ability to change people’s cost-benefit calculations, NATO continues to shape public support for military intervention.

Social cues influence the foreign audiences of an intervening country as well. Analysis of news articles, historical polls, and original survey experiments shows that NATO and the liberal community’s cues similarly affect Japanese support for U.S. humanitarian interventions, just as they do in the U.S. domestic context. These results contribute to debates about American soft power and challenge the notion that NATO’s influence is limited to the West. Turning to foreign elites, a representative survey of UK parliamentarians reveals that they prefer humanitarian intervention with NATO but without the Security Council’s approval over the reverse. In contrast, neither NATO nor the Security Council significantly affects Egyptian public opinion, which instead is more strongly influenced by the Arab League. These findings are consistent with the social cue theory, reinforcing the importance of ingroup cues. Taken together, the evidence shows that the liberal community and NATO can legitimize humanitarian wars by sending powerful social cues to domestic and international audiences.

The final two sections revisit the existing literature on how international institutions affect domestic and foreign opinion on war, demonstrating this Element’s broader contributions to the field of international relations. Section 6 reinterprets existing studies on international law and rational information transmission, showing that evidence previously seen as consistent with legal or material theories can be explained through the lens of social cues. The section also presents additional analysis to test more specific claims made by the existing theories, focusing on political knowledge. These analyses ultimately uncover empirical patterns that can only be explained by the social cue theory. Section 7 discusses the academic and policy implications of the Element. It explains how the Element advances our understanding of legitimacy, forum shopping,Footnote 28 and the role of identity in international relations, and concludes by contemplating practical questions about humanitarian wars led by the democratic community.

2 A Theory of Social Cues

This section develops a novel theory of social cues to explain how political communities and international institutions legitimize, and thereby influence, people’s perceptions of armed humanitarian intervention. Legitimization is understood here as a social process in which some stimulus leads people to conform to their social group and view a particular behavior or opinion as consistent with their identity. The theory proceeds in two subsections: first, as a general argument on how social groups send institutionalized social cues; and second, as a specific application on how IOs influence humanitarian wars by the liberal democratic community in the post–Cold War era. The section subsequently examines alternative explanations, questions of generalizability, and how the social cue theory distinguishes itself from rational informational theories. The section concludes by outlining the findings presented in the subsequent evidentiary sections.

2.1 The General Argument

The social cue theory begins with premises rooted in social and political psychology, including social identity theory (SIT), but innovates theoretically to advance a new framework for understanding how institutions convey social cues. People develop social identities when they identify with a particular group. These social groups can form around ascriptive attributes like age, race, and gender as well as ideologies, hobbies, professions, and other qualities. Identification with a group creates a sense of belonging, distinguishing “us” from “them.” This “ingroup-outgroup” distinction shapes people’s understanding of their social world, a concept central to SIT. Scholars of international relations similarly highlight how group identification and ideology foster inclusion, exclusion, and relational comparisons, influencing behavior and preferences in international affairs.Footnote 29

Identifying with a group also means acquiring a stake in the group’s collective well-being and adopting the group’s perspective. For example, individuals may feel pride based on the performance of their sports team, ethnicity, or country. This phenomenon involves developing a sense of social self or collective social identity,Footnote 30 which leads people to experience “collective self-esteem” and emotions based on their group’s experiences.Footnote 31 Collective identification also leads people to make intergroup comparisons (which contrasts with comparisons between self and others at the individual level).Footnote 32 They will care about how their group interacts and relates to other groups.

This concept of collective identity is central to international relations scholarship, which shows how the social belonging of countries, governments, and their citizens influence their preferences and behavior in international affairs.Footnote 33 For example, German citizens adopting their national identity may think about the world from the perspective of their country, Germany, as a social actor in international politics. Research in international relations also emphasizes how social identities can transfer from country to individual: if countries belong to a larger social group, then that country’s citizens will also tend to perceive themselves as belonging to such a group. For example, Germany is a part of Europe, so to some degree, Germans share a collective European identity.Footnote 34 Overall, countries and their citizens can develop ingroup identities based on economic, political, social, and other factors, in addition to geography.

Extensive research documents how people’s identities affect their opinions, decisions, and behavior both as individuals within a group and as someone who has internalized their group’s collective identity. One of the most consistent findings in this area is ingroup favoritism, the tendency to favor those within one’s identity group. This favoritism can be observed in a wide range of actions, from essential services like providing health care to smaller acts of assistance like helping a stranger who has dropped their groceries.Footnote 35 In international relations, this tendency influences humanitarian aid, where individuals are more inclined to help foreigners sharing their racial or religious background.Footnote 36 A notable example arose during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where a shared European identity contributed to widespread receptivity toward Ukrainian refugeesFootnote 37 – a response that contrasted with the more limited support for Syrian refugees fleeing conflict.Footnote 38 Ultimately, ingroup favoritism is a well-documented phenomenon influencing various aspects of social, economic, and political interactions globally.

Beyond ingroup favoritism, people identifying with a group are more likely to adhere to its views and behave consistently with its norms and practices. This tendency, in part, is driven by self-esteem: people seek to feel good about themselves, and they often adopt their group’s standards as a measure of self-worth and status. For instance, academics are socialized to feel validated by publishing in particular research journals or achieving specific career milestones. From a more rationalist perspective, people’s incentive to affirm their identities can be interpreted as an “identity-based payoff,” where people gain satisfaction from the identity-affirming actions of themselves and others.Footnote 39 Individuals might also follow their group’s behavior and norms for less calculated and more instinctual reasons, out of habit, emulation, and herd mentality. This can include a natural aversion to standing out or appearing deviant within a group to which they feel deeply connected. In this way, both calculated and subconscious motivations contribute to individuals’ alignment with their group’s values and practices.

Following this line of thought, I argue that social cues influence people’s opinions and behavior by operating on their desire to conform to and affirm their identities. The dynamic of social cueing occurs when a “sender” sends a cue to a “recipient,” and the recipient perceives the sender as belonging to its social group. The transmission of a social cue could be direct or indirect. For example, a sender could relay its opinion directly to a recipient, or a sender can publicly declare its opinion on a matter while the recipient observes that declaration. Cues include statements or actions that endorse a point of view, type of behavior, or policy. However, they do not rely on imposing a direct material cost or benefit on a recipient’s behavior, distinguishing them from coercive threats or inducement.

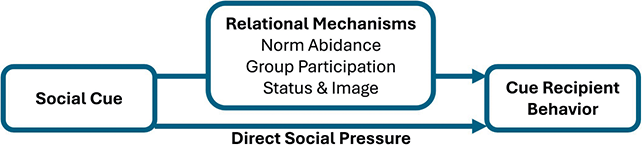

These social cues influence people through two main channels, illustrated in Figure 1. The first channel involves relational mechanisms, which tap into the following three key preferences stemming from people’s social identity. Preference number one is norm abidance, or people’s desire to behave consistently with their group’s norms and practices and advance their group’s values and goals, rather than those of an outgroup.Footnote 40 They may find intrinsic value in upholding the group’s values, while they also may fear social disapproval for violating group norms or going against their peers. This adherence can reflect a commitment to a specific norm or a broader, more intangible desire to do what is “right” or “appropriate.” For instance, a Christian may strive to uphold specific norms around charity, marriage, and the family, or more generally, seek to embody what it means to be a “good” Christian. In this sense, social cues push individuals to behave consistently with their group’s values.

Figure 1 Conceptual schema of social cues. Social cues channel their influence through social-relational mechanisms and by exerting direct social pressures to conform.

Preference number two is group participation, or people’s desire to be part of their group’s activities. People often prefer to do things alongside their peers, whether going out for a movie or engaging in a multilateral foreign policy. On the other hand, people may also have a “fear of missing out” when they are left out of the activities of their social group. Social cues thus induce this desire to be part of the community.

Preference number three is status and image, or people’s desire to maintain a high status and a good image among their peers. For many, maintaining a good image serves not only as an intrinsic source of self-esteem but also as an instrumental way to secure a sense of high status within a group.Footnote 41 This desire can lead to social ladder-climbing behaviors as well, as individuals seek recognition and approval. Furthermore, this drive for status and a positive image often extends beyond the individual to the group as a whole: people want their group to be respected within an even larger, superordinate community. For instance, a tennis player may want to be well-regarded among her fellow players while desiring that tennis itself to be well-regarded relative to other sports. Thus, social cues act upon these concerns about status and image, which in turn influence people’s opinions and behaviors. Together, these three mechanisms – norm abidance, group participation, and status/image – help to explain how social cues influence people’s opinions and behaviors.Footnote 42

The second channel of social cues operates more directly, affecting individuals through direct social pressure. In this case, social cues prompt recipients to adopt certain beliefs or behaviors without explicit reward, punishment, or incentive. Instead, recipients change their opinions or behavior through an almost automatic or instinctual process of emulation, mimicking, and conformity. This direct pressure might be described as a “normative nudge,” and there is no intervening mechanism in its causal pathway. In summary, social cues play a dual role of social influence: they ameliorate social-relational concerns, while also directly socializing group members into conformity.Footnote 43 From the surface, this dual role can be interpreted as conferring legitimacy on a point of view or behavior among a particular social group.

Who or what types of entities can send social cues? The sender of these cues can be individuals, groups of individuals, or formal bodies or organizations. Among these, cues from ingroup members exert the strongest influence. Indeed, experimental research shows that people update their beliefs and change their behavior after gleaning information from fellow group members.Footnote 44 Other studies show that cues from the like-minded can influence people’s trade attitudes.Footnote 45 Yet other research finds that cues from social peers can influence public opinion as strongly as those from political elites.Footnote 46 Within a group, cues from veteran or high-status members tend to be more influential than those from novices.Footnote 47 By contrast, cues from outgroup members are generally discounted or even met with resistance, especially when the outgroup is perceived negatively or is socially distant.Footnote 48

Social cues are particularly impactful when they are institutionalized. In international relations, for example, international organizations (IOs) can institutionalize the cues sent by certain countries or groups of countries. In this context, institutionalization designates a cue-sender as representing a particular social group using rules, titles, or formal organizations. Furthermore, such a designation can elevate the status of a cue-sender within their community. For example, a religious leader with a specific title can send cues about the social implications of various behaviors for members of a particular religion. The role of a religious leader is institutionalized (e.g., a church pastor or an abbot of a temple), which places them in a better position than other ingroup members to send social cues about what constitutes identity-congruent behavior. To provide another example, the European Union and its high commissioner are formal institutions that could effectively send social cues to the community of European states and citizens, compared to other ingroup members like the German government or some high official that happens to be European.

Institutions, when recognized as representing a social group, can amplify the impact of a social cue in two related ways. First, institutionalization clarifies the social meaning of a cue. Individuals, countries, and other entities often have multiple identities, so a cue’s social meaning may be ambiguous to observers. Take, for example, a pastor named Mike, who is also a parent, political party member, and engineer. If Mike, dressed in everyday clothes, shares a political opinion at a town hall meeting, fellow religious group members might be unsure whether to interpret his views through a religious lens or as influenced by his other roles. However, if he expresses the same views from the pulpit, members of his religious community are likely to interpret and respond to his statement within the context of their shared faith and identity.

Second, institutions can play a “logistical” role by coordinating group decision-making and facilitating the delivery of a social cue to group members. Even if individuals (or states) share an identity, they may have difficulty agreeing on a group’s goals, agenda, and actions. And even if they are aligned, they may struggle to effectively communicate their views to the broader group, especially if the group is large or dispersed. Institutions address these challenges by facilitating group decision-making and promoting communication through channels like traditional and internet media, mailing lists, and gatherings, enhancing the visibility and reach of its viewpoints. So, overall, social cues sent through institutions representing an identity group are likely to have greater reach and provide clearer guidance on ingroup norms.

To summarize, the social cue theory argues that people are more likely to support policies and engage in behavior endorsed by their social group while discounting the opinions of outgroup members. These endorsements, or social cues, influence ingroup behavior both directly – through a “normative nudge” effect that encourages emulation and conformity – and indirectly by mitigating relational concerns about norm abidance, group participation, and status and image. Social cues are particularly strong when delivered through institutionalized channels, such as formal organizations representing the group. This process of social cueing ultimately serves to legitimize certain behaviors and viewpoints for group members.

Before turning to the issue of humanitarian intervention, it is crucial to elaborate on the social cue theory’s main requirements. For social cues to work, cue recipients need to identify with the social group of the cue sender, but only to a minimal degree. Namely, cue recipients need only have some sense, whether explicitly or subconsciously, that they belong to the group. This standard most closely aligns with SIT, particularly from the minimal group paradigm tradition.Footnote 49 From this perspective, even trivial things like being sorted into the blue or red group can be the basis of group identity,Footnote 50 though if the identity marker is too trivial, it may not be a stable and long-lasting identity. Similarly, for institutionalized social cues to work, ingroup members need to have some sense, whether explicitly or subconsciously, that the institution is associated with their social group.

Two important points follow. First, members of a social group can still be susceptible to social cues even if they lack detailed knowledge of their group’s norms. For example, a person may consider themselves a member of the U.S. Republican Party. Similarly, someone who identifies as Christian may not be familiar with all the ways their beliefs and actions align (or don’t) with their faith. However, both of these individuals would still be susceptible to social cues by their group. Second, a social group can form around a certain set of values but abandon those values over time while still waving the group’s banner. This phenomenon could lead to organized hypocrisy in identity politics. Thus, one can identify with a social group and be susceptible to its social cues without necessarily understanding, internalizing, or keeping pace with its evolving values and practices.

2.2 Social Cues by the Liberal Community and NATO

In three parts, I will now apply the general formulation of the social cue theory to international politics and, specifically, to understanding how international institutions legitimize and, therefore, influence the domestic politics of humanitarian wars waged by liberal democracies. This discussion will generate a series of hypotheses regarding how the Security Council, NATO, and their member governments affect people’s views on humanitarian intervention, which will be tested in the subsequent empirical sections.

The first part of the argument establishes the liberal democratic community and NATO as the social group and institution most central to the phenomenon of armed humanitarian interventions. The United States, along with other liberal democracies, is the primary participant of humanitarian interventions, and substantial research on political communities suggests that these countries are embedded in a broader social grouping of democratic countries. This democratic community distinguishes itself from outgroup countries governed by authoritarian regimes, closed economic systems, and those with limited fundamental rights.Footnote 51 This us versus them perspective was undoubtedly promoted during the Cold War, with both sides framing the world as ideologically divided between good and bad systems.Footnote 52 While such a perspective may have been elite-driven and motivated by material interest, the notion that democracies share an identity gained traction and continued to shape foreign policy and identity even after the fall of the Berlin Wall.Footnote 53 This democratic identity also influences how various political actors, including the public, perceive which states are “friends” or “foes.”Footnote 54 Indeed, reflecting on the resilience of political identities, Peter Katzenstein noted that political actors “attribute far deeper meanings to the historical battles that define collective identities than to the transient conflicts of daily politics.”Footnote 55

Beyond representing a distinct social group, the liberal community is defined by a shared set of norms and practices.Footnote 56 Members follow a “logic of appropriateness,” or a set of beliefs about how they should behave,Footnote 57 which may be formally codified or informally accepted and adhered to as part of a “community of practice.”Footnote 58 For liberal democracies, this means governments and their citizens alike tend to avoid coercive bargaining or violence in interstate relations, although this courtesy may not extend to interactions with outgroup nations.Footnote 59 Relevant to this study, these democracies also uphold norms of consultation, emphasizing the need for collective deliberation with other democratic states in foreign policy.Footnote 60 As a result, democracies often take the policy endorsements of other group members into serious consideration.Footnote 61

Other research demonstrates how the social distinction between democracies and non-democracies influences international politics. On a macro level, democratic ideological and normative group distinctions affect which states wage war with one another,Footnote 62 form military alliances,Footnote 63 and perceive other governments as threats.Footnote 64 An analysis of UN General Assembly voting records even reveals that commitments to liberalism create a coherent “liberal order” grouping in international affairs.Footnote 65

Group behavior among countries – whether it be the deliberation of policy or conduct of joint operations – often occurs within a multilateral IO. When it comes to the democratic community, a long tradition of scholarship observes that NATO is emblematic of this group of countries, particularly in contrast to other IOs like the Security Council.Footnote 66 This line of research, often traced back to Karl Deutsch and colleagues’ seminal 1957 study of the North Atlantic community, links NATO’s role its member countries’ commitment to shared norms and values.Footnote 67 Subsequent research shows how NATO’s function as a political community of norms and values further sheds light on its operational practices, institutional survival,Footnote 68 as well as how its members maintain peace and engage in conflict.Footnote 69 NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe can be understood in terms of social identity community building by liberal democracies as well.Footnote 70 Thus, while the democratic community exists as a group of countries, NATO has become a key institution embodying its social identity and place in international relations.

To be clear, understanding NATO as a social community does not negate its role as a military alliance. These functions are not mutually exclusive and may even be complementary. In fact, even NATO itself recognizes its dual mission of providing security and advancing democratic norms and group cohesion. Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has explicitly placed promoting and defending liberal democratic values and community on par with its security mandate. This is evident in NATO’s Strategic Concept documents, which serve as its primary public statements that articulate its purpose, principles, and goals. The early Strategic Concepts (1950–1968) emphasized NATO’s strength as a military alliance, though they still acknowledged its interest in safeguarding democracy. Beginning with the fifth Strategic Concept in 1990, however, NATO has increasingly emphasized its social role in building and embodying a “shared community” of democratic values. The 2022 Strategic Concept, for example, states on its first page:

We remain steadfast in our resolve to protect our one billion citizens, defend our territory and safeguard our freedom and democracy. We will reinforce our unity, cohesion and solidarity, building on the enduring transatlantic bond between our nations and the strength of our shared democratic values. We reiterate our steadfast commitment to the North Atlantic Treaty and to defending each other from all threats, no matter where they stem from.

This statement underscores NATO’s dual identity, reflecting its mission to uphold both democratic ideals and military security.Footnote 71

In sum, NATO can be understood as an ingroup IO for democratic nations.Footnote 72 In contrast, the Security Council has a more diffuse and less defined social identity, which, according to social cue theory, limits the influence of its cues. While the Security Council includes some democratic members, it also represents a range of nondemocratic states and thus reflects a broader range of the international community. Indeed, a defining feature of the Security Council is its heterogeneous membership.Footnote 73 If it exclusively represented nondemocratic governments, it might convey an outgroup social cue, but as it stands, it occupies an ambiguous position in terms of ideological and social alignment with the democratic community.

The second part of the argument turns to the micro-level and assesses how the democratic community and NATO’s representation of it manifests within individuals. For the social cues to influence attitudes toward humanitarian interventions, a meaningful segment of people within democratic countries must identify, at least loosely, with the broader liberal community. According to the social cue theory, individuals need only a minimal or “thin” identification with a group for such cues to take effect. Often, people associate with a group before internalizing all the group’s values. This means that not all members of the liberal community will necessarily understand or strictly adhere to its norms, practices, and ideals. Rather, it is enough that people feel, even if just implicitly, that other liberal democracies and NATO are “on the same team” and constitute their ingroup. By holding this basic degree of identification, individuals become susceptible to social cues, though a stronger group identification may amplify these effects. This section supports the plausibility of these assumptions regarding people’s identity attachments.

A substantial body of research theorizes and documents how identities in international relations manifest at the individual and mass public levels.Footnote 74 Within the liberal community, people’s values and identification with other democracies are shaped by elite communication, news media, education, and public discourse.Footnote 75 Studies show that democracy and its values affect both mass public and policymaker attitudes toward international affairs.Footnote 76 For example, research from the transpacific region shows that democratic leaders’ appeals to shared liberal values affect citizen attitudes toward military alliances.Footnote 77 Relatedly, global opinions about China’s rise as a superpower vary significantly based on people’s democratic orientation, even when controlling for national security and economic interests.Footnote 78

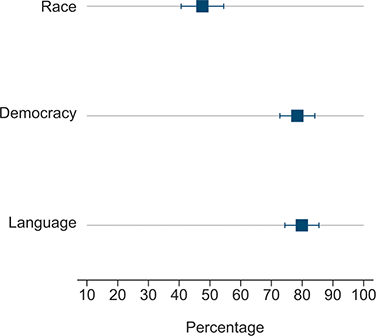

Corroborating these findings, Figure 2 presents data from a survey of Americans and shows that about 78 percent of the respondents believed that sharing a political system was at least “Somewhat Important” in determining whether citizens of different countries could relate to one another. Eighty percent saw language, a key marker of shared identity, as important.Footnote 79 In contrast, only about 45 percent considered race an important basis for international relations.

Figure 2 Americans can better relate to foreigners from democratic systems. Question asked, “What allows people from different countries to relate with one another?” The percentages capture those who responded somewhat, very, or extremely important, as opposed to not very or not at all important. N = 704. Survey USA-5.

Additional research documents how NATO membership affects public beliefs and values related to liberal democracy. For example, after joining NATO, countries like the Czech Republic and Romania adopted textbooks and implemented educational campaigns that promoted democratic frames of thinking, prompting citizens and elites to prioritize and see liberal values and human rights as legitimate.Footnote 80 This experience reflects a broader pattern of liberal democratic community-building in Eastern Europe, where NATO has served as a socializing force, fostering identification with democratic norms and values.Footnote 81

More recent examples from NATO’s public diplomacy provide additional evidence of how it fosters a collective identity among individuals. NATO states, as a core tenet, that it “promotes democratic values and enables members to consult and cooperate on defense and security-related issues.”Footnote 82 To this end, NATO and its affiliates often portray the alliance as a value-driven, group-oriented community. For instance, in June 2017, NATO tweeted, “We are an Alliance of like-minded countries … We are united … #WeAreNATO.”Footnote 83 Another tweet from the U.S. Mission to NATO highlights the group’s ideational commitments, “SecDef Mattis: For nearly 70 years the #NATO alliance has served to uphold the values upon which our democracies are founded.”Footnote 84 Similarly, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, tweeted, “NATO is the most powerful and successful alliance in history, and it’s built on the foundation of shared democratic values.” Beyond these social dynamics, NATO’s attempt to foster a collective identity can also be understood in strategic terms: if its members share an identity, they are more likely to contribute to the organization’s overarching goals.Footnote 85

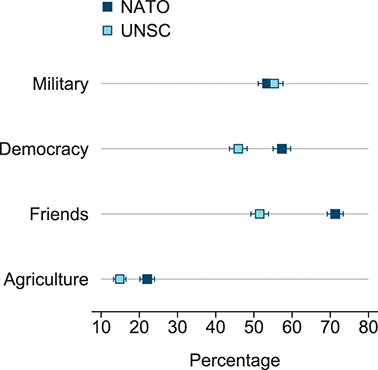

Whatever the motivation, these acts of socialization lead individuals in the community to identify with the larger group. Indeed, American public opinion reflects NATO’s dual role as a military alliance and emblem of the democratic community. Survey results summarized in Figure 3 show that most Americans associate “NATO” with the terms friends, democracy, or military. Notably, they are more likely to associate NATO with ideas relevant to a liberal community, such as friends and democracy, than they are with the Security Council. Another telling result is that friends is the most frequently selected term, aligning with the concept of ingroup identification and reflecting NATO’s role as more than just a defense alliance.

Figure 3 Americans associate “NATO” with the military, democracy, and friends. Question asked, “What do you associate with the [North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)/United Nations Security Council]?” Response options were randomized. N = 1,790. Data are from Survey USA-6.

The third and final part of the argument explains how the liberal democratic community sends social cues regarding humanitarian intervention to ingroup members. Here, countries within the liberal community – especially those institutionalized through NATO – act as cue senders, while citizens in these countries, from laypersons to policymakers and elites, are the recipients. In this setting, social cues take the form of policy positions adopted by foreign governments and institutions like NATO.

Social cues are observed in legislation, legislative votes, and statements or speeches by state officials and leaders, among other behaviors. More broadly, governments and international institutions convey their perspectives through political communication and news media, influencing public discourse. For instance, NATO sent a social cue when the North Atlantic Council voted to authorize intervention in Kosovo in 1999, a decision relayed through news media and political speeches, such as President Bill Clinton’s address to the American public. By contrast, an example of a social cue sent through legislative voting includes the UK Parliament’s 2013 vote against a U.S.-led intervention in Syria, which was covered in American news media.Footnote 86 Even outside institutional frameworks, individual foreign leaders and other elites can also directly influence public opinion, as Hayes and Guardino (Reference Hayes and Guardino2013) document in their study of the 2003 Iraq War. These policy positions can then be channeled to citizens through the media and the rhetoric of domestic elites attempting to bolster policy support by referencing the endorsements of “foreign voices.”

The liberal community’s policy endorsements act as social cues that influence members of its ingroup. These social cues exert social pressure, prompting group members to adopt the sender’s stance on humanitarian intervention. As theorized, social pressure directly prompts an instinctual alignment with a particular set of preferences or behaviors. They also indirectly mitigate social-relational concerns about the implications of intervention for members of the liberal community. In doing so, social cues address three key questions about how intervening would affect one’s country. Is intervention in line with group norms, which include championing liberal values and human rights, and is it simply appropriate or the right thing to do? Will other ingroup countries also participate in the intervention? Will engaging in intervention harm or improve their country’s status or image?Footnote 87 The answer to these questions influences people’s understanding of pro-norm behavior, group belonging, and status and image, ultimately influencing their support for humanitarian intervention policy.

Next, we can elaborate on the specific role of NATO in institutionalized social cues by the liberal community. As discussed in the general theory, NATO can clarify the social meaning of cues sent by its member states while also amplifying the reach of these policy endorsements. First, in clarifying social meaning, NATO can help audiences interpret the motives behind a member state’s actions. When a state endorses a course of action, it may not be immediately clear whether the support reflects the broader liberal democratic values or narrower national interests. For instance, if the UK backs military intervention, it could be for specific national interests rather than a stance on behalf of the democratic community. However, when the UK makes the same recommendation under NATO’s banner, the endorsement takes on a more communal significance, as NATO symbolizes the collective liberal democratic community. In this way, NATO strengthens the social cue by clarifying its social meaning within the democratic community.

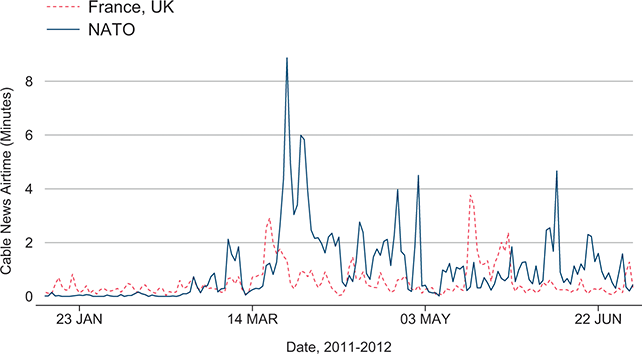

Second, NATO serves an amplification role, enhancing the logistical coordination and communication reach among member states and the public. For governments, NATO helps coordinate decisions across the community,Footnote 88 increasing the likelihood of reaching shared policy positions, such as on intervention issues. Without this organizational framework, individual governments may struggle to reach or communicate collective decisions. For the public, NATO can increase the prominence of the democratic community’s policy cue, as its media presence often surpasses that of any single member state.Footnote 89 The following empirical sections highlight how NATO receives substantial coverage in both print and television media, far outpacing individual member states. This visibility supports NATO’s role in amplifying the community’s voice, ensuring that its policy endorsements reach a broad audience.

In conclusion, social cue theory offers a coherent and distinct perspective on the social dynamics within the liberal community regarding humanitarian interventions. It suggests that the liberal community can influence democratic citizens through ingroup social cues, which gain even greater power when channeled through institutions like NATO. Furthermore, once citizens receive such a policy endorsement (or rejection) from NATO, they are more likely to discount the views of outgroup members or institutions with mixed identities, such as the Security Council. These cues are influential because they exert social pressure and provide social guidance, helping individuals understand how to fit in and gain good standing within the community of democracies.

2.3 Caveats and Clarifications

This section discusses alternative explanations for NATO’s apparent legitimizing effect, the generalizability of the theory, and how the social cue theory contrasts with existing informational theories of international institutions.

2.3.1 NATO’s Alternative Effects

The social cue theory predicts that NATO and the liberal community should strongly influence how members of the liberal democracy ingroup think for social identity reasons. But could there be other reasons why these ingroup cues affect people’s policy preferences? I lay out two such alternative reasons here, which I evaluate empirically in subsequent sections.

The first alternative explanation relates to people’s material considerations. People may believe that IOs facilitate burden sharing. If they do, an endorsement by an IO like NATO could imply that their country would have to expend fewer resources to participate in the intervention. While existing research on burden sharing does not necessarily conclude that NATO would be superior to the Security Council in facilitating burden sharing, this is a reasonable alternative explanation.Footnote 90 In particular, when NATO supports intervention, it usually means it will commit material resources to that cause. A related material logic is that people may follow NATO’s cues because they perceive it to be a strong, competent military alliance capable of conducting military intervention.Footnote 91 This military capability relates to burden sharing, but it could also improve the likelihood of a successful intervention, and people tend to like successful policies.Footnote 92 All of these material mechanisms relate to the “output” or performance of an institution, which existing research documents as statistically associated with people’s perception of institutional legitimacy.Footnote 93 The observable implication of this material alternative explanation is that people’s estimations about the costs and benefits of war should mediate the relationship between NATO’s cues and people’s support for intervention.

Second, a nonmaterial alternative explanation focuses on Western regionalism. It similarly emphasizes identity and ideational factors rather than material and security concerns. Scholars have long observed that NATO, the North Atlantic community, and even the broader liberal community overlap with a racial or geographic group centered in North America and Western Europe.Footnote 94 Related work also argues that the “Anglosphere” constitutes a distinct transnational identity that impacts international relations, including forming military coalitions in interstate uses of force.Footnote 95 From this perspective, NATO’s influence should be understood as an ingroup signal among white Western countries rather than among democracies more generally. One implication of this argument is that NATO’s effect should operate only within Western liberal democracies.

Each of these arguments provides an alternative logic for why people might respond more enthusiastically to a NATO-backed intervention compared to one authorized by the Security Council. While they are not necessarily mutually exclusive with the social cue theory (these mechanisms can be additive, for example), the empirical sections demonstrate that they cannot explain away the social cueing mechanisms articulated in my theory.

2.3.2 Generalizing Across Policy Domain, Time, and Political Actors

The influence of social cues could be contingent on three factors. The first is the issue domain. The theory is being applied to the realm of armed humanitarian intervention. Rathbun (Reference Rathbun2007) observed that, at least among elites, supporting one’s community is a fundamental foreign policy value, and such a disposition strongly predicts support for humanitarian military operations. This observation implies that social considerations might be especially important in policies like humanitarian intervention, where other-regarding motivations are salient. In contrast, social considerations might hold less weight for critical national security matters. For example, a country responding to a foreign invader would care little about seeking institutional approval to defend itself.

The second is the time period. The theory in its general form – that IOs representing an identity can send social cues – is being applied to the case of the post–World War II liberal community and, more narrowly, their conduct of humanitarian interventions since the Cold War. As a social theory, the specific application must be contingent on the social context. For example, it is hard to imagine that a social group of democracies was salient in earlier centuries. Some may also argue that in the era of U.S. President Donald Trump, democracy may once again retrench from being a salient identity grouping in global politics, especially since elites have leeway to shape popular perceptions of legitimacy.Footnote 96 However, whether President Trump’s rhetoric has fundamentally shifted American identity in world politics remains an open question. In fact, after Trump assailed NATO during his first presidential campaign, the U.S. Congress reacted by bringing forth a bipartisan resolution to affirm the U.S. commitment to NATO.Footnote 97 A PEW study also found that “[w]hile Trump recently called into question the value of U.S. participation in NATO, Americans overwhelmingly view NATO membership as beneficial for the United States … Large majorities in both parties say NATO membership is good for the U.S.”Footnote 98

In any case, the theory does not claim that identities last forever. While identities and their resulting discourse and mass-level constraints may be stable in the short and medium run,Footnote 99 they can change in the long run.Footnote 100 Nevertheless, even if the specific application may change, the social cue theory provides fundamental theoretical lessons about social identity and the legitimizing role of institutions in international politics, which I further discuss in the conclusion.

Finally, social cues may operate differently on different political actors. This Element focuses on domestic and international public opinion, which are intrinsically important political actors for the aforementioned reasons. Section 5 provides some evidence regarding foreign elites, but elites are not the focus of my study. So, one might ask, does the theory apply to elites? For example, lawyers in the State Department may prioritize legal considerations. Military elites may prioritize considerations about burden sharing and operational success. Policymakers may already be directly informed about foreign policy matters and do not require a second opinion from an international institution.

But while different elites may have distinct priorities, they are also people, and recent research cast doubt on the exaggerated distinction between elites and the public.Footnote 101 One might even argue that when it comes to foreign policy, elites are even more socialized than the mass public into specific modes of thinking, given their deeper and more direct exposure to international politics. Indeed, the Washington Post analyzed polling by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and found that “[a] new poll suggests that maybe American voters and D.C. foreign policy elites aren’t so different after all.”Footnote 102 Specifically, the analysis found that

Despite Trump’s harsh words about NATO, a consensus exists among all groups polled that the United States should either maintain or increase its commitment to the organization; fewer than 1 in 10 in any group supported leaving NATO. Meanwhile, though Trump had questioned the wisdom of U.S. support for allies such as Japan, South Korea and Germany, there was widespread support for keeping U.S. military bases in these countries.

Corroborating this logic, some existing studies find that IOs do not just influence mass opinion but elites as well. For example, Schultz (Reference Schultz and Drezner2003) argues that a president seeking to wage war can invoke an IO’s authorization to help break gridlock among domestic elites. Likewise, Thompson (Reference Thompson2009) argues that IOs, and particularly the Security Council, can convince foreign elites to support war. Furthermore, elites themselves often explicitly express their desire for institutional legitimacy. For example, leading up to the 2011 Libyan intervention, top policymakers, including U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, considered “international authorization” to be a necessary condition for intervention (Chivvis Reference Chivvis2014, 55). Lastly, established research on European supranational identity generally implies that elites may be even more socialized in international norms and identity than the mass public, given their direct participation in international politics, travel, and cross-border exchange.Footnote 103

One might point out another way elites differ: they form their opinions in a group setting; however, existing research casts doubt on whether group opinion formation differs fundamentally from that of individuals.Footnote 104 Lastly, even if elites like military officers have different priorities,Footnote 105 many are still sensitive to pressure from the masses.Footnote 106 So, overall, the social cue argument could contribute to understanding elite behavior as well, both directly as elites are subject to social cues and indirectly as they consider the general public.

2.3.3 Contrast with Information Transmission Arguments

While not logically mutually exclusive, the social cue argument is distinct from existing information transmission theories of international institutions in three main ways.Footnote 107

First, existing theories model the process of information-seeking as a means to an end. People seek an informational heuristic to reduce uncertainty about the objective outcomes of a policy. In this case, citizens or foreign elites seek to make an educated guess about whether humanitarian intervention will produce good outcomes. On the other hand, from the social cue perspective, the cue itself is important, and the policy’s objective outcome may even be secondary. The cue itself is an act of socialization that creates social pressure while alleviating concerns about norms, status, and group behavior. From the information as a heuristics perspective, cues solve the problem of not having insider or “encyclopedic” knowledge about a policy. From the social cue theory’s perspective, even cue recipients with “encyclopedic” knowledge who can make informed decisions would still be influenced by social cues.

Second and closely relatedly, the information transmission and social cue theories focus on different causal mechanisms. Given its emphasis on policy outcomes and motives, information transmission theories tend to focus on the logic of consequences in material, cost-benefit terms. From this view, people are asking questions such as, will intervention cost my country blood and treasure, and will it succeed in achieving the foreign policy objective? Informational cues, as defined in the literature, answer such questions. In contrast, social cues exert social influence and operate through relational mechanisms. One could perhaps still call this “social information” and, therefore, also information, but the contents of the mechanism are different. In addition, the social cue theory further emphasizes the effect of direct social pressure, which is not informational in the sense that it causes the cue recipient to update their beliefs about the world.

Lastly, the social cue theory provides a distinct explanation for why some sources of cues matter and others do not. Ingroup cues matter most, especially when sent through an institution that has been accepted by the community to represent the identity of the group. In contrast, the information theories present a range of other factors: for example, cues from those with distant policy preferences (i.e., conservative pivotal voters), cues from diverse, independent, or neutral committees, and cues from an elite coalition. These are clearly different theories, primarily drawn from the game theoretic tradition, that lead to different hypotheses about which sources of cues matter.

One final information perspective, also from the game theoretic tradition, that comes closest to the social cue theory argues that cues from similarly biased sources can relay useful information as a heuristic.Footnote 108 While this perspective has not been fully theorized in the context of IOs and war, the social cue theory does share some insights with these arguments in its focus on like-minded cue givers. Nevertheless, the social cue theory can still differentiate itself for the first two reasons stated earlier: social cues are the object of concern in and of themselves, operating through social pressure and relational mechanisms, rather than a means to an end for the cue recipient to estimate the material consequences of a policy or other behavior. Beyond these two major differences, the social cue theory further provides a deeper set of explanations and testable implications for how socialization and institutionalization of the cue giver affect these dynamics. By contrast, from the informational heuristics perspective, the cue recipient only needs to know the policy preference of the cue sender to update their beliefs based on the cue. Thus, the social cue theory provides a distinct set of propositions about whose cues matter and why, which the remainder of the Element tests.

2.4 Outline of Empirical Sections and Research Designs

The subsequent empirical sections test various implications of the social cue theory as outlined next. Section 3 assesses the effect of social cues sent by the liberal community and NATO in the U.S. context. It does so by examining historical cases and original experimental data from surveys. Section 4 demonstrates the mechanisms of social cues, distinguishing the social causal pathways from material alternative explanations. Section 5 examines the effect of social cues on foreign audiences, and Section 6 (re)assesses arguments from the extant literature relating to international law and information transmission.

Observational evidence from American interventions (Section 3): Historical polls from 1990 to 2013 show that humanitarian interventions backed by the liberal community and NATO enjoy high support from the American people. The Syria case shows that IO approval is critical for raising public support. Comparing Bosnia and Kosovo shows that NATO, with or without the Security Council, can generate public support.

Causal evidence of social cues on domestic audiences (Section 3): Survey experiments show that cues from NATO and the liberal community cause American support for humanitarian intervention to increase. Once Americans learn about NATO’s position, the Security Council has little effect, but not the reverse. These effects are even stronger among the attentive public than among the mass public, implying that NATO’s cues are not primarily serving as informational heuristics for the ignorant, as existing theories might imply.

Institutionalized cues (Section 3): Additional experiments show that the liberal community’s influence on public opinion is more substantial when institutionalized via NATO. Corroborating these experimental results, during the Libya crisis, NATO also received more cable news television coverage than its component countries, showing that IOs receive more salience than specific countries in the real world.

Analysis showing the relevance of ingroup perceptions to NATO’s influence (Section 4): NATO’s endorsement effect is greatest among (1) those who express the strongest affinity with NATO’s member countries and (2) those who associate NATO with democracy and community. In contrast, NATO’s influence on public opinion is not impacted by its association with military power, contrary to the material considerations alternative explanation.

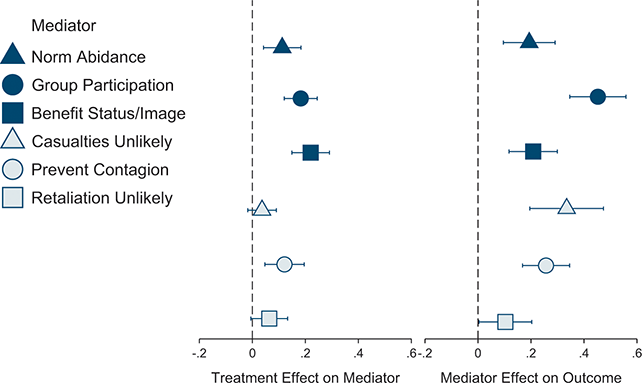

Analysis of the social cue’s relational mechanisms (Section 4). NATO’s cues activate people’s social concerns about norm-abidance, group participation, and status and image. These factors, in turn, affect people’s opinions on intervention. In contrast, material considerations relating to financial and human costs and benefits cannot fully explain the cueing effect.

Foreign audiences (Section 5): The relative effects of the liberal community, NATO, and the Security Council, as well as the impact of institutionalized cues, reported in Section 2, are all replicated in Japan. This finding contrasts with the alternative explanation of Western regionalism. Next, NATO and the Security Council do not significantly affect Egyptian public opinion, but the Arab League does. This finding is also consistent with the social cue theory.

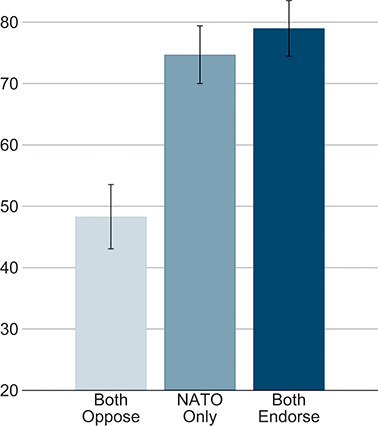

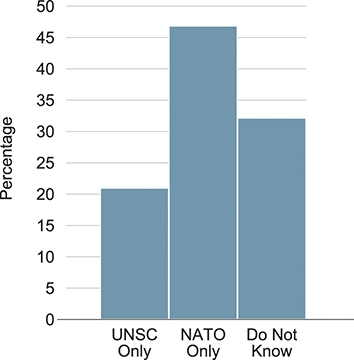

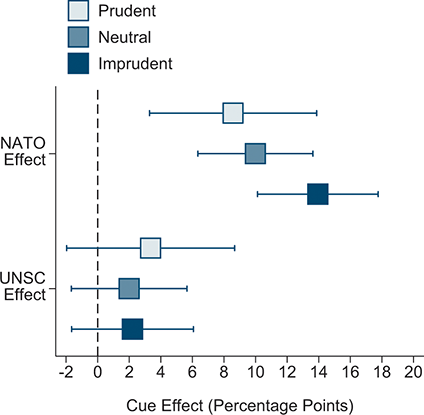

Foreign elites (Section 5): Substantially more members of the United Kingdom Parliament (MPs) would rather receive NATO’s backing for humanitarian intervention than the Security Council’s if they could only have one or the other.

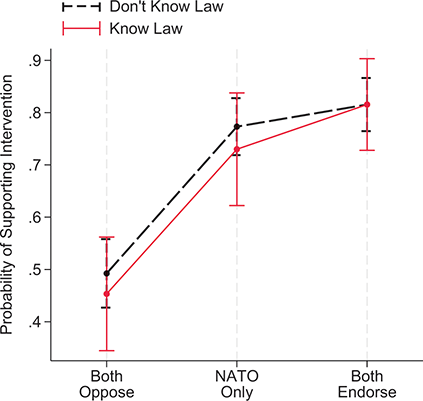

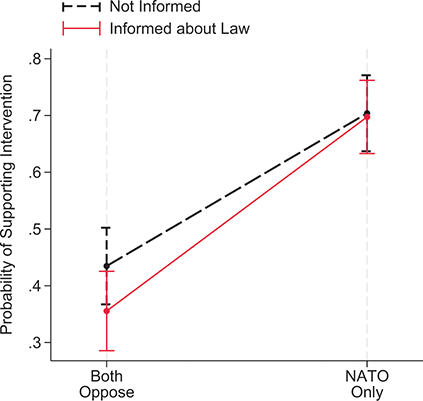

Reconsidering legal perspectives (Section 6). This section provides additional observational and experimental evidence showing that the Security Council’s lack of influence is not due to people’s ignorance of international law.

Reconsidering arguments about information transmission (Section 6). Existing theories predict that a neutral and conservative institution like the Security Council should affect public opinion, while a relatively homogenous and hawkish institution like NATO should have a weaker effect. Yet, the evidence thus far shows nearly the opposite. This section presents additional analysis to show that the Security Council’s relatively weak effect is not due to political ignorance. People largely view the Security Council as relatively neutral and conservative. Individual-level data on people’s understanding of the Security Council and NATO further show that people’s assumptions about institutional neutrality and conservativeness do not moderate the institution’s effect on public opinion.

3 Evidence from American Interventions

My fellow Americans, today our armed forces joined our NATO allies in airstrikes against Serbian forces responsible for the brutality in Kosovo.

This section tests the claim that democratic countries seeking to boost domestic support for humanitarian intervention can achieve this by securing the endorsement of international institutions. The analysis focuses on the United States, which plays an outsized role in modern humanitarian interventions as either the primary intervening force or a key contributor of financial, political, and military support. If the social cues theory holds, then the liberal democratic community, mainly through NATO, should significantly influence American support for military action.

Drawing on multiple forms of evidence, the following two sections demonstrate that the liberal community and NATO shape American public opinion. The first section explores American views on intervention from Somalia to Syria, using historical polls, media coverage, and presidential speeches from these cases. The second section presents original experimental data from U.S. opinion surveys to assess the causal impact of IOs on public opinion. Consistent with the social cue theory, NATO exerts a distinct causal effect on American public opinion, beyond that of the Security Council. The experimental analysis further separates the impact of IOs from that of their member states, revealing that NATO allows the liberal community to send institutionalized cues that carry more weight than the signals sent by individual member countries alone.

3.1 The Post–Cold War Historical Record

Since the end of the Cold War, armed humanitarian interventions have primarily been a policy of the liberal democratic community, with the United States leading the majority of these actions. Each of these interventions has been multilateral, conducted under the auspices of an international organization such as the Security Council or NATO. Conversely, intervention efforts have been abandoned when institutional approval proved unattainable. This section reviews historical opinion polls from episodes of U.S. interventions, focusing on the case of Syria and a comparative analysis of Bosnia and Kosovo. Syria highlights the challenges of rallying support for unilateral intervention, while the Balkan cases illustrate how NATO can drive humanitarian action with or without Security Council endorsement.

What do the broad, descriptive patterns tell us about the post–Cold War era of humanitarian intervention? Table 1 summarizes the historical relationship between the Security Council, NATO, the liberal community (independent from NATO), and American public support for humanitarian intervention.Footnote 109 It includes cases in which the United States considered humanitarian intervention and opinion polling data were available. Column 1 names the case. Columns 2 through 4 give the policy position of the Security Council, NATO, and the liberal community. NATO’s policy position on intervention is generally equivalent to the policy position of the liberal community. But when NATO did not consider the case of intervention (i.e., when NATO is N/A in the table), the country positions of the liberal community are coded using public statements and actions of NATO’s member states. Finally, Columns 5 and 6 give the percentage of respondents who supported intervention, both for each case and for the aggregation of cases that fall under the same category of multilateralism. The Online Appendix provides detailed notes for each case, its coding, and survey wording.

Table 1 American support for armed humanitarian intervention, from Somalia to Syria

| Cases | Endorse Military Action? | % Supporting Military Action | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security Council | NATO | Liberal Community | By Case | Average | |

| Rwanda 1994 | No | N/A | Mostly No | 28 | 31 |

| Syria 2013 | No | No | No | 33 | |

| Kosovo 1999 | No | Yes | Yes | 53 | 53 |

| (Libya 2011) | (No) | (Yes) | (Yes) | (56) | (55) |

| Somalia 1992 | Yes | N/A | Mostly Yes | 74 | 55 |

| Haiti 1994 | Yes | N/A | Mixed | 34 | |

| Bosnia 1994 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 57 | |

| Libya 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 56 | |

Note: This table summarizes data from historical surveys conducted in the United States during episodes of potential humanitarian intervention. NATO is coded N/A when the case was considered “out of area” at the time. The Rwanda poll was taken before France’s Operation Turquoise, which received Security Council approval. The Libya case might be classified under “NATO Only” because the Security Council resolution arguably did not cover the airstrikes that led to a regime change. Polls are from the Cornell Roeper Database.

The record reveals three broad categories of humanitarian intervention: those with no systematic international support (e.g., Syria), those backed by NATO or the club of democracies but not the broader international community via the Security Council (e.g., Kosovo), and those with widespread international backing (e.g., Bosnia). Public opinion across these categories suggests a clear preference among Americans for interventions with international backing. Only 28–31 percent of the public supported intervention without foreign approval, while a majority supported interventions with some degree of IO approval (about a 22–25 percentage point difference in support). Interestingly, in comparing the second and third categories of interventions, Americans do not appear to differentiate interventions with both Security Council and NATO approval from interventions with only NATO approval.Footnote 110 These patterns are consistent with the identity theory’s prediction that once a cue from the ingroup is received, the additional cue from other countries contributes minimally to public support.

3.1.1 Syria: Unpopular Unilateralism

The case of Syria illustrates the difficulty of legitimizing and mobilizing mass support for humanitarian intervention without broad international approval, even when other factors would predict high support for intervention. Following the Arab Spring, opposition to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime escalated into a civil war by 2012. The conflict was brutal, and there was clear documentation of mass war crimes and human rights violations by the Assad regime.Footnote 111

Several conditions would predict strong public support for intervention in Syria. First, the scale of human rights abuses and civilian casualties in 2011 and 2012 created a significant humanitarian crisis. Second, the civil war created massive international spillover effects. As early as 2012, hundreds of thousands of refugees had already fled the country, and by 2013, that figure grew into the millions.Footnote 112 Third, one of the most widely respected international norms was violated: the taboo against chemical weapons.Footnote 113 In 2013, the Syrian government used nerve gas and other chemical weapons to kill over 1,000 civilians.

Fourth, American credibility was on the line. In 2012, President Barack Obama publicly stated that “[w]e have communicated in no uncertain terms with every player in the region that that’s a red line for us and that there would be enormous consequences if we start seeing movement on the chemical weapons front or the use of chemical weapons.”Footnote 114 This view was broadcast widely among the American and international public. Indeed, when chemical weapons were subsequently used, Obama began earnestly courting domestic and international support for military intervention in Syria. If action were not taken in response to the use of chemical weapons, American credibility would be harmed, and Americans have been shown to care about their leaders following through with their promises, including threats.Footnote 115

Fifth, respected domestic elites advocated for military action, particularly within the Democratic Party. President Obama – a highly popular leader – made a strong case for intervention, supported by prominent figures such as Secretary of State John Kerry.Footnote 116 These elite endorsements, in theory, should have boosted domestic support for intervention.Footnote 117

Given the scale of the humanitarian disaster, international spillover effects, violation of international norms, cost of American credibility, and elite cues among the Democrats, one would expect high public support for intervention in Syria, especially among Democrats. However, such expectations did not manifest. Multiple opinion polls conducted in late 2012 revealed that less than 35 percent of Americans supported military action, even if intervention was limited to airstrikes. Furthermore, Democrats were about as equally skeptical of intervention as Republicans.Footnote 118