1 Introducing Louise Lowe

‘Poverty stings, under the skin, we can’t be afraid to acknowledge it,’ theatre artist Louise Lowe reflects in one of the many interviews undertaken since 2011 when I first encountered her work (Lowe and Boss, Reference Lowe and Boss2023). This study of Lowe’s theatrical practice will be framed significantly by her personal experience of childhood poverty and its lifelong impact on her creative and social sensibilities. My very first interview with Lowe occurred after experiencing Laundry (Figure 1) in 2011 (ANU, directed by Lowe), a site-specific performance in Ireland’s longest running Magdalene Laundry building located on Seán McDermott St Lower in Dublin’s north inner city, formerly Gloucester St (ANU, 2011; Haughton, Reference Haughton2014a; Singleton, Reference Singleton2016). The most recent interview with Lowe occurred a few weeks prior to this Element’s publication. Throughout those fourteen years in between, Lowe has emerged as Ireland’s leading theatre director whose creative abilities extend beyond the traditional theatre roles such as ‘director’ and ‘playwright’, and the parameters we associate with them. Attempting to categorise or classify her roles or abilities will not produce any groundbreaking insights into her theatrical practice, motivations, or productions. Asking which role(s) she inhabits is not the right question for this study. Instead, asking where she is from and what she is driven by will bring us closer to understanding the work she makes, why she makes it and how she makes it. Essential to any study of Lowe’s work is her primary experiences of community and care networks in Dublin’s struggling north inner city and how these bonds activate her own vision for artistic encounters in contemporary society. Lowe’s insights in this regard shape her work in direct and intense ways, which inform the research rationale and ideological structures underpinning this study.

Figure 1 Laundry (2011). Performer Sorcha Kenny,

Lowe wrote her first play Diptych in 1996 for Dublin Fringe Festival and the Belfast Festival at Queens followed by a national tour (‘Louise Lowe’, Irish Playography). Since then, Lowe writes, directs, and casts for theatre primarily with more recent professional commissions occurring in television and film. ANU Productions was formed and registered as a production company in 2009 by Lowe and Owen Boss as co-Artistic Directors, mirroring their now well-established reputation for collaborative practice in all aspects of their creative process. Lowe’s contributions are most often captured in ANU’s theatre programmes and publicity materials as a director and playwright, while Boss is often credited as set designer and visual artist. Both admit their nomenclature has never felt like a perfect fit, and they change their titles as the specific needs of any given production demands (Lowe, Reference Lowe2021b; Boss, Reference Boss2024). For the first decade of ANU’s work, Lowe rarely credited herself as the playwright in addition to the director, though in many productions, she was the first or primary writer of the script. However, the scripts she writes for ANU productions operate as moving documents, referred to as a ‘show document’ in rehearsals (Lowe, Reference Lowe2021a) which is regularly shifting, absorbing the contributions of performers, designers, production crew, or, indeed, anyone in the rehearsal room and performance space while the performance is being constructed, rehearsed, and revised (Boss, Reference Boss2024). Furthermore, once the ensemble of performers is cast, the performers choose their own ‘characters’ which thus informs the shape and scope of the script further. Úna Kavanagh, a founding ANU ensemble member and regular performer, notes that the word ‘character’ does not fit right in her mouth (Kavanagh, Reference Kavanagh2024) most likely as the ‘characters’ are a selection of historical figures being re-presented in live performance encounters. Every narrative they recount and audible or physical suggestion they infer is developed from historical and archival records. In short, Lowe’s work with ANU is rarely fictional in root and stem. The performers identify which historical figure they wish to bring to life as part of a sustained research phase of the rehearsal period. Following this, scenes can be formed, timed, and put into a rotation structure, as Lowe’s work with ANU usually has a minimum of two starting points of approximately three to eight audience members per scene. Then, the dialogue can be firmly cemented alongside the embodied encounters, dance performance, live art, and installation art that are often essential ingredients of ANU’s work.

This Element will assess Lowe’s creative practice and production history since her early days as a drama facilitator in prisons and resource centres in her native Dublin, Ireland (1995–2000). However, as recognised from the outset, it is vital to open this study reflecting on how her own experience of childhood poverty is a fundamental part of her creative DNA. It was visible in Laundry (2011), the first ANU production directed by Lowe that I experienced, capturing the economic vulnerabilities of the women institutionalised throughout the twentieth century in Ireland as part of an oppressive and punitive culture dictated by a conservative Roman Catholic hierarchy. Their influence extended throughout the legal, civic, and bureaucratic apparatus of the newly formed Irish state (1921–1922), a state struggling for legitimacy and rendered vulnerable by centuries of poverty, colonialism, and war. The voices of those woman – poor, exploited, violated, and abandoned – remained silenced for almost a century in Irish public discourse (Smith, Reference Smith2007; Haughton et al., Reference 66Haughton, Pine and McAuliffe2021; McGettrick et al., Reference McGettrick, O’Donnell, Smith, O’Rourke and Steed2021). Laundry remains part of my own DNA as a theatre scholar and audience member, marking a shift in my own critical and emotional capacities to invest in performance as world-making. The production confronted the various, distinct, and historically specific experiences of women and their families in granular detail with nuance and sensitivity, highlighting experiences rarely acknowledged officially for the majority of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in Ireland. It remains embedded in memory for those who experienced it, established as a landmark moment in contemporary Irish theatre and performance. Laundry simultaneously communicated the complexities of institutionalisation in Ireland, and, re-asserted the role of the arts to symbolise, critique, engage, and inform a contemporary Irish society emotionally drained by decades of fiscal corruption (European Commission), weak governance, and bankrupt religious teachings (O’Toole, The Guardian Reference O’Toole2018). However, while my own feminist connection to Lowe’s work may be easily traced through her platforming of women’s experiences, Lowe’s primary artistic motivations are rooted in her own background and formative experiences submerged in the economic struggle of Dublin’s north inner city, the markings of which are potently visible in the work she makes and how she makes it.

This following stark statistic is difficult to digest yet it captures the significance of Lowe’s motivations and influences. In Lowe’s final school class of eighteen students in 1992, six remain alive. Lowe discusses this with Irish drag queen and writer Panti Bliss in 2020 (Pantisocracy podcast/video), but three years later, that number has fallen to four (Lowe, Reference Lowe2023). In some parts of the country, Lowe argues a ‘social genocide’ has occurred that seems to have gone unnoticed (Pantisocracy). She emphasises ‘poverty’ with a sense of urgency when she speaks of it, which must be considered separate from standard definitions of ‘working class’ (Cambridge Dictionary), though she is highly attuned to class demographics in Irish theatre and beyond. Language – words such as poverty, class, and disadvantage – cannot fully capture her personal experience of childhood nor that of any individual, collective or group. It makes sense then that her work is so driven by physicality, choreography, and bodily intimacy, not only in its presentation to audiences but through its choreography of audiences as an essential aspect of her dramaturgy. Lowe stages stories by centring the bodies of her performers, audiences, and the communities in which her productions take place. This centring of the body simultaneously underwrites the potency and precarity of humanity, the impact and affect of which ripple outwards. According to Catriona Crowe, former Head of Special Projects at the National Archives of Ireland who has collaborated with Lowe and ANU on multiple commissions as part of Ireland’s ‘Decade of Centenaries 2012–2023’ (DoC), Lowe has a unique capacity to confront the truth of complex past experiences, absorb them, and re-present them in performance in a way that does not detract from the pain, while enabling a cohesive encounter for audiences to engage with and, thus, examine (Crowe, Reference Crowe2023). Her method and style of ‘confrontation’ of seismic events are not didactic, Crowe asserts with great caution (Crowe). Rather, she envisions a diversity of experiences, facts, archival legacies, perspectives, and, indeed, contradictions to present distinct positions of a past event. Crowe’s comments chime with ANU’s consideration of ‘Cubist dramaturgy – [by] exposing multiple sides and states simultaneously’ (Kavanagh and Lowe Reference Kavanagh and Lowe2017, p. 119). Lowe and Kavanagh, reflecting critically on ANU’s creative process, explain the central contention of this dramaturgical approach:

As much as possible, we try to avoid exposition, believing that its absence opens up a kaleidoscope of myriad possibilities. Deploying (on top of this), a cubist dramaturgy – by exposing multiple surfaces and states simultaneously – we invite audiences to create their own multi-fractured narratives, becoming auteurs of their own instinctive experience.

Lowe’s confrontation of the ‘kaleidoscope of myriad possibilities’ of historical narratives is a method of examining the past empathetically to come to terms with the present. The twenty-first century, thus far, remains as challenging economically, socially, and politically as the century previous. Yet, perhaps by confronting historical roots of injustice in intimate theatrical encounters for both audiences and performers, one might begin to reimagine the potential of the present moment that decouples the value of society from neoliberal priorities that continue to subsume national governance regardless of the social consequences. In short, there is no way to rationalise fourteen deaths from a class of eighteen coming of age approximately thirty years ago. There is only the opportunity to acknowledge it, examine it, and, indeed, question whether the root causes of such inequity have changed?

1.1 Co-Creation, Golden Tickets, and Ticking Clocks

Lowe’s show documents are constantly subject to change. At final stages of rehearsal prior to previews, this document is often abandoned as the implicit understanding surfaces that it is no longer required (Haughton rehearsal notes, The Wakefires rehearsals 2022; Hammam rehearsals 2023). Durational, second-specific performance scenes transform from actions and lines that must be embedded into muscle memory as part of the performers’, designers’, and technicians’ daily routine, logistically conceived, supported, and monitored by ANU stage manager and performer, Leanna Cuttle. Cuttle’s role in the artistic, logistical, and communal development and presentation of ANU’s performances, often invisible to the audience, is essential. If rehearsal of a scene results in a single-second overrun, Cuttle returns the company to first positions to start again, continuing to drill the performance until the exact timing is achieved. At this moment, the ‘Clock is King’ mantra takes hold. As one audience member or small group leaves an encounter, the next individual or group enters it, and thus, scenes cannot run over their allocated time. If an immersive encounter with an audience member takes up too much time or an error of some kind delays the scene’s timing, performers must decide to cut something forthcoming to save the seconds that were lost. The ‘Clock is King’ policy must be adhered to in order to facilitate the full performance to unfold, thus ensuring time and space for the ‘Golden Ticket’. The ‘Golden Ticket’ is where a performer invites a single audience member to learn something new that the remaining audience members do not learn, see or experience. As part of this one-to-one moment, they are removed temporarily from the audience grouping with whom they entered the performance space. Lowe asserts that ‘it should matter that you’re [the audience] there’ (Reference Lowe2013), and this philosophy manifests as a leading dramaturgical thread in all her work that is produced by ANU. Part of the ‘Golden Ticket’ concept is enabling the audience to ‘feel, witness, comply or act’ (Joye and Lowe Reference Joye and Lowe2015, p. 141) in response to provocations and invitations made by the company in performance. By ensuring time and space arises for the ‘Golden Ticket’ to take place, Lowe and ANU carve out a deeply personal and memorable experience for the audience member who finds themselves invited to participate in this interaction.

The level of creative vision that results from the synergies between Lowe and her co-artistic director Boss, a visual artist by training, may complicate further singular suggestions of authorship when reflecting on performances in their holistic shape. Indeed, this Element is acutely aware of the complexities in presenting The Theatre of Louise Lowe as a creative endeavour she pursues in isolation as it is precisely due to her particularly potent abilities for interconnection and collaboration that has resulted in her standing as a unique artistic visionary of the twenty-first century. She also leads the casting process for her productions, and in recent years, she has worked as a TV and film director and screenwriter in Ireland (ANU, Abbey Theatre, Gate Theatre, Landmark Productions, RTÉ, Screen Ireland) while her live performance work is increasingly commissioned internationally (LIFT These Rooms 2018; BAM-commission The Cholera Season in 2019, cancelled due to COVID) as her reputation gathers momentum. There is no doubt that Lowe is a playwright in addition to a director; however, this study is hesitant to conclude that Lowe is any singular title such as ‘director’ or ‘playwright’ in isolation, as the last decade has shown how swiftly her skillset extends and reforms, often in response to the cultural, social, and political conditions informing the arts sector more widely.

Throughout two decades of creative practice, Lowe’s theatrical loyalties have remained rooted in the struggling working class of Dublin’s city centre. Crowe praises her ability to absorb Irish events and histories considered too traumatic to be addressed comprehensively in political and cultural circles, while suggesting a concern for what impact this may take on Lowe, or indeed artists more generally, who regularly delve into the most troubling parts of social history. Lowe’s experience of poverty marked her childhood and her access to theatre and the arts in ways that continue to inform her work. Indeed, how does one reconcile the vying issues of modest representations of class and poverty in Ireland (Pierse, Reference Pierse2017, Reference 70Pierse2020) alongside potential exclusion of those very communities from attending theatre due to ticket prices? It is worth qualifying this issue to suggest that any such exclusions are unintentional as the wider economic contexts for theatre production are so financially precarious that to remove or reduce ticket prices could mean production is no longer viable. Regardless, the fact remains that the cost of the ticket is a discretionary expense for most people, and communities that suffer economic hardship on a regular basis do not possess discretionary funds. Lowe’s work, predominantly produced as part of ANU Productions, begins from the premise that they make work with communities, not about them (Lowe and Boss, Reference Lowe and Boss2023). ‘Production’ is not a fitting bandwidth for what they do (Lowe and Boss, Reference Lowe and Boss2023) as seeking dramaturgical satisfaction in any conventional sense of beginning-middle-end stories, with a central conflict resolved within 90 minutes, is a fool’s errand, or, perhaps, a theatre critic’s one.

This Element opens with this snapshot of Lowe’s early years to understand the depth of Othering her experience of poverty resulted in, and, indeed, the bonds of kinship that she became nourished by from her tight-knit community in similar circumstances. Born in Foley Street in Dublin’s north inner city in 1974, Lowe is loyal to presenting stories of vulnerable communities, particularly those areas that suffer economic deprivation and the legacies that arise from it. In her youth, Lowe regularly visited Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery. There was (and remains) no entrance fee to the national art galleries and museums in Ireland, though certain special collections may require costed or timed tickets. Lowe became drawn to Renoir’s Les Parapluies (The Umbrellas), a painting that foregrounds a woman in working-class attire, exposed to the elements without the shelter of a hat or umbrella in contrast to those surrounding her. Her expression is difficult to read, but amidst the jostling crowd, a sense of isolation emanates. Lowe’s connection to this image is telling; it speaks to the hierarchies that dominate public space. Raised in a community ravaged by Ireland’s first heroin epidemic in the 1970s (RTÉ Archives, Reference Archives1972), these childhood experiences marked how she perceives community, equality, and political systems. The visit to this gallery became followed by visits to other galleries, and eventually theatre, as a sense of personal connection to artistic environments began to develop. Lowe understands the transformational potential that art can offer any individual, claiming ‘theatre saved me’ (Reference Lowe2023). It is difficult to challenge her insights into the development of her own artistic abilities, but I would suggest that rather than ‘saving’ her, theatre tapped into abilities she already possessed, perhaps providing her with the confidence and conditions for those abilities to thrive. Introducing The Theatre of Louise Lowe must begin with this consideration of economic deprivation as a formative experience, but there are other significant strands of artistic experience that constitute her motivations and desires for the work she makes. The impact of growing up in Dublin’s inner city has taught her the importance of community and of enabling communities to speak with their own voice rather than being spoken for.

1.2 Lowe, Owen Boss, and ANU Productions

Lowe and Boss first met while undertaking a postgraduate certificate in Youth Arts in the academic year of 2004–05, awarded through Maynooth University with the National Youth Council of Ireland. They both recall that they fell out spectacularly on their first day during a heated conversation regarding what may constitute art (Lowe and Boss, Reference Lowe and Boss2021). For Boss, it could be anything: no limits, no borders, no rules. For Lowe, intention and skill were fundamental ingredients for an activity, encounter, or object to earn the title ‘art’. Despite a testy start, they became good friends during their programme which examined how to work with young people outside of mainstream education through art (Boss, Reference Boss2024). At the time, Boss reflects how nervous and shy he was, while Lowe was Artistic Director of Roundabout Youth Theatre in Ballymun, a northern suburb of Dublin developed in the 1960s to accommodate social housing during a national housing crisis. The impact of working in Ballymun and the history of Ballymun carry significant weight in terms of the Lowe-Boss collaborative journey and the formation of ANU more widely, as it encapsulates some of the founding elements of ANU’s blueprint for developing work. This blueprint includes foregrounding community-led concerns, marginalised groups and individuals, complex social histories, and patching together an alternative modern history of the island of Ireland from the voices and perspectives of those born and raised in some of Ireland’s most vulnerable communities.

Lowe and Boss’s first co-production took place in Ballymun with Lowe’s youth theatre group from that area. For background, some of Dublin’s inner-city communities were relocated to Ballymun before the newly developed residential area had sufficient civic infrastructure in place to support its residents. The area became synonymous with a boisterous community spirit in addition to major social challenges. The ‘Ballymun flats’, high-rise tower buildings that were new to Dublin’s architecture, became visually symbolic of Ireland’s struggling economy from the 1960s to the early 1990s in Dublin, before the Celtic Tiger economy propelled newer imagery associated with the speedy rise of the urban middle class, a phenomenon occurring much later in Ireland than in European counterparts. As Irish author and journalist Fintan O’Toole details, Dublin Corporation initially considered what became known as the Ballymun flats as ‘system-building experiments’ (O’Toole, Reference O’Toole2016). According to O’Toole, the motivations for this type of residential construction were steeped in a political ideology that was bordering on desperation to enter modernity in the same vein as London, Paris, and other European capitals. As he recalls of the time, ‘Ireland was sick of being a rural idyll of underdevelopment and mass emigration … Hard as it is to reconcile with the later history of the place, Ballymun was part of the new optimism’ (Reference O’Toole2016).

Widely documented in the decades since the construction of the Ballymun flats, those required amenities did not materialise. Sufficient public transport links between the area and the city centre were not in place. Ballymun became culturally associated with the concept of no man’s land, reserved for the most economically and socially vulnerable, out of sight from the centre. O’Toole summarises both the civic and the psychological space of Ballymun following decades of poor planning, insufficient investment, and fundamentally, a lack of care by the political mainstream:

By the mid-1980s traditional families were already reluctant to settle in Ballymun and the tower blocks were disproportionately occupied by single mothers and their children, by single men (many recently moved from institutional care) and by people who had been homeless. Few of them had access to the income, jobs, services, and supports they needed. And because they were often politically disempowered the authorities did not feel pressure to maintain the blocks to a decent standard (2016).

Lowe understood the experience of growing up in a community disavowed by the centre. By 2004, the first of the towers were demolished and by 2015, all were gone. Their homes and community spaces, problematic as they were, were literally bulldozed into oblivion before their eyes. Ballymun’s young people became the ensemble that formed Lowe and Boss’s first production, Tumbledowntown (Reference Lowe and Boss2005).

The impetus for this first collaboration between Lowe and Boss was a practical one, with both required to complete a practice project for their coursework. Boss had no experience working with young people, but Lowe invited him to collaborate with her ensemble as part of Roundabout Theatre. While Boss’s background was fine art, he recognised their synergies during their course. One task they were required to complete as part of their studies was to distil their thinking and practice regarding working with young people into three words. For Lowe and Boss, two of their three words matched: autonomy and quality. These priorities set the tone for how they make work together. They successfully applied for public funding through a scheme called ‘Breaking Ground’, and Boss recalls, ‘That wouldn’t have come from me, that was Louise’s motivation and determination’ (2024). Boss reflects on Tumbledowntown’s artistic process as the seeds of what ANU became driven by in future years:

[…] taking over an abandoned flat in Ballymun, working with 26 people of the youth theatre over the course of a summer, working through visual art, through theatre and sound, and looking at this general theme of past, present and future in Ballymun and what it meant to them. So that was basically the core idea … and I think that became the blueprint of what ANU would become …

Lowe and Boss considered their youth group ‘experts’ as it was their experience and local knowledge that was fundamental to the creation of a narrative and aesthetic experience. Boss also recalls that Lowe’s earlier work with the group rendered the entire production possible, explaining, ‘even to get young people from that area to stand in a room and actually engage with art is a win’ (Boss). Without her laying the foundations with the young people, ranging in age from approximately 14 to 18, Boss doubts that they could have completed the project.

This ‘blueprint’ included other key fixtures that would appear regularly throughout the next twenty years of work. First and foremost, Lowe and Boss work from the premise that they make work with communities, not about them. They are particularly interested in working-class histories, oral histories, and histories of those who have been disavowed by canonical narratives established throughout the twentieth century, often inextricably linked from a nationalist desire to set ideological parameters regarding the priorities and identity of the Irish nationhood project. They were and remain interested in different artforms and exploring the potential for cross-pollination, working off site or in very loaded sites for approximately 4–8 weeks, depending on the availability of casts, crew, and resources in general. Over time, they could see the cultivation of familial dynamic, one which fostered a clear sense of purpose regarding the distinct significance of each production and its impact in revealing historical narratives and experiences previously sidelined, suppressed, or overlooked. Many of the cast return again and again, but Lowe and Boss ensure that with each new production they ‘blood new people’ (Boss, Reference Boss2024). They invest in the process, and everyone’s voice matters in rehearsal while constructing scenes and encounters. Boss summarises Lowe’s role in the creation of this ethos and working environment, stating, ‘I think people would run through a brick wall for Louise, she has that capacity, she has that almost leadership role, like people say that about football managers, “I’d run through a brick wall for them”’ (Reference Boss2024).

This commitment to community is most transparently captured in Lowe’s and ANU’s process and how they situate their audiences at the centre of the work. ‘Co-presence’ as leading ANU scholar Brian Singleton posits in ANU Productions: The Monto Cycle (Reference Singleton2016) is an essential strategy that she incorporates in her work, intensely visceral in Laundry whereby audiences were challenged ‘at moments of committal and escape from the asylum/laundry […] as well as to assist, interact and bear witness’ (Singleton, p. 2). Indeed, her strong sense of belonging to a community also underpins the formation of the ANU ensemble with whom she makes the majority of her work. ANU offers a shared vision of art, creativity, and innovation in terms of form, style and intention, but it also offers Lowe community, belonging, and a sense of support in making the work as she envisions it, which rarely corresponds to a singular artistic discipline, but pushes at the intersecting boundaries of ‘performance, installation, visual art, choreography, site-responsive and community arts’ (Singleton, p. 1).

These formative and artistic influences deeply inform her motivation to reframe audience experiences in Ireland. Lowe’s core philosophy regarding the intersection of performance and audience that ‘It should matter that you are there’ (Lowe, Reference Lowe2013a) implicitly challenges the convention of much standard modern theatre in Ireland comprising end-on staging with audiences in darkness and a hefty fourth wall keeping that distance. In this style of staging work, how much does it matter if the audience is there? Engaging new audiences, capturing and keeping audience attention, generating inspiration, and activating critical engagement can be sought, but again, at a polite distance. However, the removal of live audiences from the performance space during COVID-19 lockdowns underlined the significance of audience presence and that without those bodies, elements of the very fundamental experience that constitutes the theatrical event changes. Some artists and critics will argue this is an existential threat, while others will advocate for the inclusion of virtual and hybrid technologies as part of innovation and shifts in practice in cultural spaces and production techniques.

Lowe’s dramaturgy is dependent on harnessing the vitality of live audience presence by removing those conditions that allow for polite distance, and simultaneously, revealing a potential for violence within these social codes of politeness. This type of audience contract, one of ‘polite distance’, aligns with a wider social contract, also ‘polite distance’. To say that Lowe reconfigures or indeed reimagines ‘polite distance’ is akin to equating the climate emergency with some weather issues. It is not that her practice bypasses theatre conventions, but, rather, reinvigorates them appropriate to the conditions of twenty-first-century experience to enable intimate connections that contemporary neoliberal social structures often prevent. As Kavanagh and Lowe detail:

By placing the audience at the very centre of our practice in order to create autonomous exchanges, we have created a new kind of hybrid theatrical model of performance. Working in real environments and slippage between the artificial and the real, we are interested in the changing nature of contemporary cultural thinking. We […] use immersive engagement to create shared intimacies between audience and place and audience and performer.

For Lowe and ANU, performance-making is an act of enquiry conducted with communities that occurs through multidisciplinary research and becomes constructed by this ‘Cubist dramaturgy’, through which they do not present a singular perspective but confront multiple perspectives, drawing from varied artistic disciplines and strategies, and most often, without offering a resolution or conclusion.

The concept of Cubist dramaturgy as a guiding methodology did not stick immediately for Boss. His background in fine art immediately provoked ideas of ‘the muse’, typically female and not always well-treated, with the Cubist masters such as Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) in particular, and Georges Braque (1882–1963). He felt the association with Cubism and the modernist idea of the male painter/genius did not fit with the work ANU wanted to make or how they wanted to make it. With time however, he has found that it can be a helpful way to explain their process of looking at ideas, people, and histories from different angles. Boss brings this background in fine art with all its loaded resonance to the work ANU makes, just as Lowe brings her particular abilities in writing, directing, and casting. Interestingly, until Boss worked with Lowe on the Ballymun project, he had not been to see theatre, with the exception of the pantomime as a child. Thus, the set design and scenographic experiences he curates with Lowe for ANU are not an explicit intention to reject the traditions of naturalistic kitchen-sink dramas or pastoral quality (PQ) so resonant of twentieth-century Irish drama. Rather, he is inspired more acutely by smells, sounds, and sites. Like the work itself, Boss explains ‘its multilayered and diverse across profession, across viewpoints, across age and to have that diversity gives us different ways of looking and responding’ (Reference Boss2024).

Singleton summarises the impact of ANU’s breakthrough performances known as ‘The Monto Cycle’ in his book of the same name. He maintains that ‘ … no one is able to capture the complexity and multiplicity of performative strategies used by ANU Productions to enable spectators to encounter the history, people, geography and very materiality of the Monto’ (Reference Singleton2016, p. 3). He identifies the driving focus of ANU’s work directed by Lowe as ‘on ‘others’, the bystanders to history, on those absent from historical constructions. But in their folding of the present into the performed past, a folding the company calls ‘NOW-THEN-NOW’, new ‘others’ emerge as bystanders, inviting us to stand by them as well’ (2021, p. 302). His research unveils the particular potency this dramaturgical motivation offers for Ireland’s intercultural and multicultural communities, platforming the diversity of Irish communities, no easy task in a nation psychologically entrenched with a monolithic narrative of nationalism characterised as white, patriarchal, Catholic, heterosexual, and rural. He details:

This otherness of ANU Productions is not strictly intercultural at first glance as most of their work in Ireland has been based on both state archives but also oral histories of communities through times of postcolonial revisionism, social deprivation and historical erasure. But it becomes intercultural, as we shall see, in moments in performance when visuality and aurality take a turn away from a monocultural past to perform in the present.

While Singleton provides a granular focus on the intercultural threads of Ireland’s past and present as captured through ANU’s work, this study will provide a direct focus on Lowe’s methods of practice which ‘unfold’ (Schneider, Reference Schneider1997, p. 2) the female body in moments of intense hardship, revealing the inheritance of church-state rule conjoined in a patriarchal capitalist nexus that continues to bear influence in state, civic, and community relations in the twenty-first century. Reading from Diana Taylor’s The Archive and the Repertoire, geographer Karen Till analyses the ‘body memory’ performed in These Rooms (ANU and CoisCéim co-production, 2016 Dublin, 2018 London) directed by Lowe. Noting that each movement has been built upon a ‘why’ Till summarises, ‘The artists critically interrogated the truth claims and silences of official institutions through creating more inclusive ‘archives of public culture’, whereby ‘possible scenarios of alternative kinds of social relations’ were made accessible to diverse audiences’ (Reference Till2018, p. 37). This method of performance research is framed by Lowe’s directorial parameters as Till examines, noting Lowe’s first response to archival materials pertaining to the 1916 North King St Massacre in Dublin was the following question: ‘What was the experience of female bodies in these spaces?’ (p. 37). This thread will be interrogated further in my close reading of The Wakefires (2022) co-produced with Cork Midsummer Festival and Hammam (2023–4) co-produced with the Abbey Theatre in Section 3 of this Element. During these productions, I shadowed Lowe during rehearsals as she juggled history, narrative, performance, design, technical demands, community responses, and, unfortunately for The Wakefires, the COVID-19 pandemic which ended the sold-out performance run following two previews attended by eight people.

As Lowe’s theatre practice is largely produced by ANU with core members of the ensemble, much of this Element’s focus is Lowe’s work in that context. It is interesting to note that Lowe registered the name ‘ANU’ in 2009, which colloquially refers to a ‘Goddess of Wealth’ though stemming from the Celtic etymology of ‘Ana’, ‘Anann’, ‘Dana’ ‘Danu’ (MacKillop, Reference MacKillop2004) with closer links to ‘giver of life’. Celtic mythology refers to ‘Anu’ as ‘The principal goddess of pre-Christian Ireland, the mother or “nourisher” of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the “people, tribe, or nation of Ana”’ (MacKillop). In 2009, Ireland was bankrupt, bailed out by the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), together comprising ‘The Troika’. Economic crisis aside, the country was bankrupt culturally and socially, and arguably spiritually, following more than a decade of abuse revelations in Ireland’s institutions and schools led by religious orders, often with state complicity and cover-ups on both sides of the border that separates Ireland from the north of Ireland (Clann Project; Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry; Justice for Magdalenes Research; One in Four; Tuam Oral History Project). However, Lowe is not referring to economic wealth but something else, a force or energy that one must have within oneself and to connect with others to live with hope, dignity, and peace of mind. That primary reach for self-constitution and meaningful connection with others drives her vision for performance, identifying visual and embodied threads for ‘ethical encounters’ (Lowe qtd in Haughton Reference Haughton2014a, p. 73) between performers and audiences in places with charged and conflicting histories.

Certain dramaturgical threads emerge on analysis of her work since The Monto Cycle began in 2010. These include the impact of poverty and class discrimination on the development of society in Ireland, the political presentation of the female body in performance contexts, the trials and tragedies of mothers as a result of capitalist, patriarchal and religious control, and the reliance on mothers for assurance of familial and community survival. However, her productions often implicitly signal that ‘mothering’ extends far beyond the literal circumstances of birth. If not ‘giver of life’ as the Celtic etymology of ‘Anu’ suggests, certainly a ‘nurturer’ or ‘sustenance’ of life becomes a point of emotional significance visible in much of her work. Finally, a sense of communion as connection with others in the immediate present as well as connection with historical legacies is paramount in how she crafts performance encounters. While analysis of text to context is the shorthand for critique of drama in traditional academic models, for this Element, it is analysis of Lowe’s practice to Lowe’s place, north inner-city Dublin, that offers the most direct and useful lens for critique.

By 2015, Lowe’s reputation for staging the experiences of Ireland’s vulnerable communities, particularly those in poverty, was established with each of ANU’s productions sold out, often in a matter of minutes. She expressed no interest in bringing to life the historical experiences of ‘posh boys’ according to Lar Joye, the then-Curator of Irish Military History at the National Museum of Ireland (NMI) in Collins Barracks in 2015 (Joye, Reference Joye2024). This history concerns the final days of a young battalion of Irishmen before they left for the battlefields of Gallipoli in 1915, most never to return, the subject matter at the centre of ANU’s Pals – the Irish at Gallipoli (2015) (Figure 2) directed by Lowe, supported by the NMI and the Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht in association with the National Archives of Ireland.

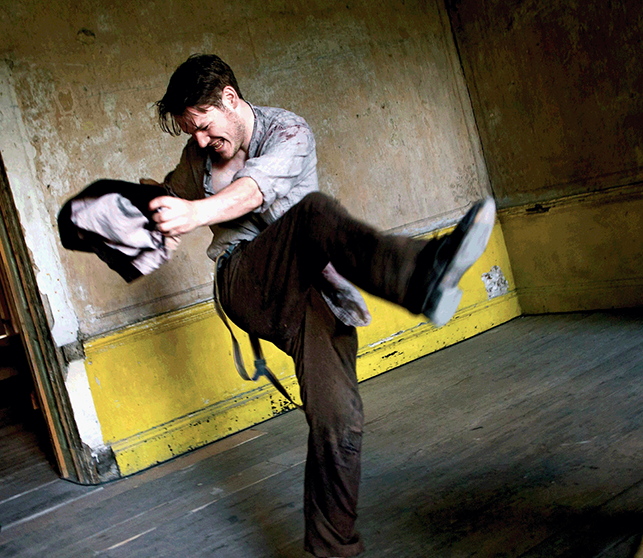

Figure 2 PALS – The Irish at Gallipoli (2015). Performer Liam Heslin,

Joye contextualises how the concept of ‘Pals’ emerged in the British army, ‘Armies rely on innocent under-25-year-olds rushing off to war because the generals don’t do the fighting. So you need young, enthusiastic men to do your fighting for you. The idea was that people from the same clubs or associations would all join up as one unit (Joye qtd in Wallace, Irish Times, 2015). Journalist Arminta Wallace contextualises how the level of present-day knowledge concerning Irish involvement in Gallipoli is modest within Irish communities, with little enthusiasm displayed for bridging that gap prior to the centenary commemorations. However, Joye found stories and images of the Irish battalion captured in the 1917 book The Pals of Suvla Bay, the ‘record of ‘D’ Company, 7th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, at Gallipoli’ (Royal Dublin Fusiliers). It is these first-hand accounts that convinced Lowe and ANU to create their work staged at the NMI. Through their research, they discovered a variety of Irish men from different backgrounds and faith sent to Gallipoli as part of the British army. The tragedy of this story is not only the intense loss of young life, but the innocence possessed by these young men believing they stood a chance against the enemy, when in reality, ‘five guys with a machine gun could stop 700. That was the horror of the new warfare’ (Joye qtd in Irish Times). Joye wanted to showcase the histories of that battalion as it demonstrates the reality that ‘when you’re 18 you can’t pick your enemy … if you don’t follow military law you get shot. I hate this jingoistic approach to war, ‘joining an army is a noble, gentlemanly pursuit’. Its not: its dirty, its violent and its brutal’ (Reference Joye2024).

Lowe and ANU’s close working ties with Joye were cemented through that production, and their impact on public engagement with the Museum audiences notable. As a result of Pals, the museum experienced ‘9,000 visitors seeing the 300 performances and increasing the museum’s visitor attendance by 34%’ (Joye and Lowe, Reference Joye and Lowe2015, p. 137). That relationship developed into future work, including On Corporation Street (2016) in Manchester, England co-produced with HOME Manchester, and The Book of Names (2021) co-produced with Landmark Productions staged at Dublin Port, where Joye is currently Port Heritage Director. Joye had initially heard of ANU’s work through Living the Lockout (2013), inviting them to screen a recorded version at the NMI. At the time, Joye reflects ‘Louise was the only one doing anything exciting about the centenary … Louise, Owen and the ANU gang are the few people who tackled the centenary properly’ (Joye, Reference Joye2024). Joye confided his feelings of dismay to Crowe regarding the inadequate resources to produce an NMI DoC programme that could achieve anything other than a ‘tokenistic’ encounter. Crowe pushed him to consider what would communicate Ireland’s complex histories in such a way so as ‘to shake people to their core and upset them and concern them’ (qtd in Joye, Reference Joye2024). He felt 1916 [the Easter Rising] was going to be ‘done to death’ and wanted to illuminate other significant events that were less known, yet equally profound in their significance to communities in Ireland and among the Irish diaspora, estimated at 70 million in 2017 (Gilmartin and Murphy, Reference Gilmartin and Murphy2024). With ANU, Joye saw the potency of the NMI’s objects and artefacts reinvigorated with new energy and opportunities to make meaningful connections with the public. He reflects the museum’s relationship with ANU was a relatively new departure for them at the time, and they ‘threw stuff at her [Lowe] for months … She took it all on … her people skills, her leadership skills are some of the best I’ve ever encountered’ (Reference Gilmartin and Murphy2024). Part of these interpersonal and leadership skills include listening and learning as a primary point of departure, which operated as a key research phase for On Corporation Street (2016) (Figure 3) in Manchester city, commemorating the 20-year anniversary of the IRA bomb, the largest bomb to explode in the UK since WWII (BBC, 2022). Prior to rehearsals, ANU conducted three major inquiries with communities in Manchester who experienced the bomb and its aftermath to gather testimony. Of this process, ANU acknowledges that ‘we were not the experts on the bomb and its effect but needed to form an archive from which to create the work. We needed to listen to the voice of the city and this repository of information was instrumental in shaping, developing and making On Corporation Street’ (ANU Inquiries: On Corporation Street 2016).

Figure 3 On Corporation Street (2016). Performer Niamh McCann,

Both Joye and Crowe led focus groups in Manchester to gain a first-hand understanding of local memories. It was during this time that Joye felt history shake him ‘to his core’, rather than intending such an impact on audiences. While listening to individuals recount their memories of the bomb, it became clear that this was the first time many of those people were asked or interviewed about it in any formal capacity. While the IRA bomb wreaked havoc and injured more than 250 people, it did not kill (BBC). As there were no fatalities, the level of trauma associated with the bomb’s impact seems to be minimised in public discourse and political action (Joye, Reference Joye2024). Listening to these oral histories, memories, and reflections gave greater credence to those experiences. They were the voices that had been overlooked despite the atrocity they suffered. If there is any meaningful point to these centenary commemorations, Joye proposes, it is whether they change anything on their conclusion (Reference Joye2024). That remains to be seen with the official centenary commemorations ending in 2023, and this Element going to press in 2025. However, Lowe’s role in the psychology of this public space is significant, particularly in staging the absent voice and body, ‘unfolding’ it as Rebecca Schneider suggests, ‘Peeling at signification, bringing ghosts to visibility’ (Reference Schneider1997, p. 2).

1.3 Element Overview

This Element will offer micro and macro analyses of productions directed and sometimes written by Lowe since the conclusion of her first major theatrical intervention, the four-part ‘Monto Cycle’ (ANU, 2010–2014) as already mentioned. Following this work, I argue there is a greater confidence and determination in Lowe’s creative voice and strategies, built upon the resilience harnessed as a result of the Monto Cycle’s impact. Inherent in what follows is Lowe’s deconstruction of gendered and classed lines in Irish social life primarily, epitomised by the character of Nannie in The Lost O’Casey (ANU, 2018) (Figure 4), a performance crafted in response to Irish playwright Seán O’Casey’s Nannie’s Night Out (1924). Nannie becomes a type of ‘Everywoman’ or ‘Every-protagonist’ for Lowe, operating not as ‘real’ representation of a particular individual but suggestive of an intergenerational encapsulation of struggling communities born into deprivation, overwhelmed by their circumstances, ostracised by the social fabric and let down by the political establishment. While O’Casey’s ‘Nannie’ is developed from a ‘real’ woman he observed, ‘Mild Millie’ (Drums under the Windows, 1945), Lowe’s various Nannies capture the ‘why’ of the struggle, and how her struggles for change are inextricably linked to place. If community conditions were tended to, restorying might emerge.

Figure 4 The Lost O’Casey (2018). Performer Sarah Morris,

Leading the analysis in various case studies throughout this Element is Rebecca Schneider’s theorisation of feminist motivations and intentions in contemporary performance art in The Explicit Body in Performance (Reference Schneider1997), which addresses the conditions faced by women artists accessing key venues for the presentation of their work beginning in the 1980s in the United States. She recalls ‘The Guerrilla Girls’ posters in New York from 1985 onwards, with one such poster asking the public ‘DO WOMEN HAVE TO BE NAKED TO GET INTO THE MET MUSEUM?’ (p. 1). This question pithily summarises centuries of women’s experience in patriarchal societies: in short, that how women are presented and represented in arts and culture is a battleground. The Guerrilla Girls refer to their strategy of intersectional feminism to undermine ‘the idea of a mainstream narrative by revealing the understory, the subtext, the overlooked, and the downright unfair’ (Guerilla Girls). Most often, it is images of women that please the gaze of the white heterosexual male for capitalist ends of endless circulation, reproduction, and profit that are regularly included, and these images do not resonate with the majority of women’s lives. Lowe presents women who do not please the gaze of heterosexual white men in neoliberal culture but who have suffered as a result of the demands, expectations and priorities of that gaze, such as how it constructs and embeds conditions of desire, power, and privilege. Schneider notes how the very name of the group refers to both gender and race that are accorded lesser status in social relations, while the masks they use ‘make explicit a social contract’ (p. 1). To render visible this social contract, these feminist performance artists utilised a strategy of ‘explosive literality’ (p. 2) through their art and actions. Lowe, and much of ANU’s body of work, also stage a type of ‘explosive literality’ that keenly questions assumptions of the social contract that appear invisible and unspoken, and yet could not be more explicit in terms of which community benefits and suffers, as Dublin GP Dr Austin O’Carroll emphasises in his developmental work for The Lost O’Casey.

O’Carroll works from an inner-city medical practice and became centrally involved in ANU’s ‘community encounters’ as part of their intense development period for The Lost O’Casey (TLOC) in 2018, written and directed by Lowe, staged at the invitation of the north inner-city community where she was raised. However, O’Carroll’s collaborations with Lowe stretch back further than TLOC, outlined further in Section 2. From his programme note, he details the frustration of seeing how the cards are stacked against north inner-city communities and such conditions become embedded and structural. Dr O’Carroll criticises the social and political conditions which result in:

[…] families who have lost several children to drug addiction, young parents and children in homelessness, young intelligent adults leaving school after their junior cert, migrant families living year on impotent year in asylum-seeker purgotary […] And then, the ultimate injustice, that same community is blamed for it’s own misfortune. Slothful social welfare scammers, worthless junkies, contemptible alcoholics etc.

TLOC will be further analysed in Section 2, yet O’Carroll’s insights are central to introducing how and why Lowe and ANU conceive of and frame their productions, performed in the streets and spaces of communities to the wonder, delight, and, indeed, discomfort of audiences and passers-by.

‘Explicit’ captures the central objective of Schneider’s study as she evokes its Latin roots ‘explicare’ meaning ‘to unfold’. From here, Schneider’s concept of ‘unfolding the body’ emerges, a concept which frames the analysis of Lowe’s work throughout this Element:

Unfolding the body, as if pulling back velvet curtains to expose a stage, the performance artists in this book peel back layers of signification that surround their bodies like ghosts at a grave. Peeling at signification, bringing ghosts to visibility, they are interested to expose not an originary, true, or redemptive body, but the sedimented layers of signification themselves.

Unfolding the body is a powerful lens through which to critique Lowe’s work. Recent productions directly stage documentary materials relating to Ireland’s Decade of Centenaries (2012–2023) which commemorate, but by no means celebrate, 100 years since the partition of the Island of Ireland into two states, the 26-county Irish state and 6-county Northern Irish state, following major wars with the British Empire and Irish Civil War (Ferriter, Reference Ferriter2022; Reference Ferriter2015). In these productions, there is no ‘true or redemptive body’ (Schneider, p. 2). Rather, Lowe provokes those ‘sedimented layers of signification’ (p. 2) to become fertile and active soil for contemporary reflection and debate. ‘Bringing ghosts to visibility’ (p. 2) is a poignant encounter in the context of the centenary commemorations, where figures such as ‘Nannie’ re-emerge from archival records, telling us their stories which did not find solace in any conventional resolution symptomatic of a functioning society.

To conclude this section, I summarise essential ingredients for Lowe’s work which will re-emerge for fresh analysis within close readings of distinct performances throughout this Element. These ingredients include that Lowe’s productions are often directly immersed in a historical stimulus, though she approaches each production as a unique and distinct encounter without a predefined outcome. She does not stage the past as it has been written or disregarded, but excavates the past to reassess and re-present ideas, legacies, absences, and questions. Lowe restorys these stimuli, contextualising them in the historical period of their occurrence and simultaneously in the contemporary moment of performance, which produces a space of self-reflection for audiences, seeing themselves as part of a social journey. Her creative team will include core members of the ANU ensemble, but will also directly involve anthropologists, architects, archivists, folklorists, historians, medics, and social scientists. Indeed, some have been interviewed as part of this study’s research methodology. Within this network of materials and expertise that she gathers with her ensemble, who become ‘dramaturgs of their own work’ (Lowe, Reference Lowe2012), Lowe stages a historically situated chain of events revealed through multiple protagonists and spaces of performance that compel, unsettle, complicate, and, most significantly within her work, remain unresolved.

2 Staging Ireland’s Nannies

2.1 Lowe’s Dublin

‘Will you let me alone, will you leave me for this?’ (Irish Street Medicine Symposium: https://www.drugs.ie/multimedia/video/international_street_medicine_symposium_2014). These are the words recalled by Dublin inner-city GP Dr Austin O’Carroll of a female patient in recovery from heroin addiction performing an autobiographical encounter from her past. O’Carroll sought Lowe’s collaboration as part of the International Street Medicine Symposium hosted by Safetynet in Dublin in 2014 (ISMS SafetyNet). Working with two of his patients, she paired them with performers and tasked them to rewrite part of their own stories. The final scenes were performed for the conference delegates, including this woman with a history of heroin addiction. The woman and the performer she worked with took their audience down an alleyway where she had frequently injected. One Christmas evening however, following ‘tapping’ (begging for money), she realised she was alone in the world. She went to this alleyway, injected, and then was approached by a young Garda (Irish language, ‘police’). She pleaded with the Garda for her solitude so that she could escape into the alternate reality the heroin provided. After a brief moment’s hesitation, the Garda turned around and walked away.

This image is both distressing and provocative. It demonstrates how abject experiences may circulate socially, including in official relations such as engagement from authorities. Thinking of ‘Nannie’ from The Lost O’Casey as a type of ‘Everywoman’ for Lowe’s work as an embodiment of intergenerational discord in Irish society, introduced in Section 1, one can see how the pull of social alienation manifests in this scene between the woman and the Garda. Both the woman and the Garda know the Garda should intervene officially, and yet, neither personally desire the intervention. Julie Kristeva considers how strange and discomforting the affect of abjection manifests in western cultural experience:

This massive and abrupt irruption of a strangeness which, if it was familiar to me in an opaque and forgotten life, now importunes me as radically separated and repugnant. Not me. Not that. But not nothing either. A whole lot of nonsense which has nothing insignificant, and which crushes me. At the border of inexistence and hallucination, of a reality which, if I recognise it, annihilates me. Here the abject and abjection are my safety railings. Seeds of my culture.

Lowe stages these seeds and invites her audience to remove the ‘radical separate[d] and repugnant’ relation into the space one typically inhabits. In order to preserve middle-class codes embedded in the social fabric – stable, comfortable and respectable – scenes of despair, bodily chaos, and social exclusion must be kept in dark alleyways, away from the centre. Did the Garda in that instance uphold unwritten social codes that one may internalise over time or abandon their duty? What do concepts of duty and society really mean when so many are enabled to exist outside of a functioning public sphere?

The image of this woman alone in an inner-city alleyway on Christmas Eve injecting heroin while begging a Garda to turn away returns this analysis to Schneider’s ‘unfolding of the body’ (p. 2) as part of Lowe’s heightened realistic aesthetic which render visible the scars on the wounded bodies from the past that Lowe revives for the present. Authorities turning away from those most vulnerable is not a new narrative in Irish theatre, as Seán O’Casey reveals in his 1945 autobiography Drums under the Windows. ‘Mild Millie’ is a woman he meets by chance one day as minds his sister’s furniture on the street, who has been recently evicted from her residence along with her children. O’Casey is waiting for a cart to arrive to collect the furniture when he sees Mild Millie. Drunk from methylated spirits, Mild Millie challenges a passing police constable and a sergeant to acknowledge her, as O’Casey describes in the story ‘Behold, My Family is Poor’. The constable advises the sergeant to ‘Take no notice of her … it’s Mild Millie – a terrible female, powerful woman, takin’ ten men to lug her to the station when she goes wild with red biddy; take no notice, for God’s sake’ (O’Casey, Reference O’Casey1945, p. 80). O’Casey reflects on how the encounter came to a conclusion, with Millie declaring, ‘It’s you, you ignorant yucks, that breed th’ throuble; g’on now, she shouted after them, for they had turned and walked away as if they hadn’t laid an eye on her or heard a word she said’ (p. 80).

Returning to Lowe’s work with the medical conference, O’Carroll later received correspondence from a medic in the United States who had been in attendance. Following a staunch refusal to provide methadone treatment to heroin addicts throughout his medical career, believing it served to replace one addiction with another, he began training to provide methadone to his patients (O’Carroll, Reference O’Carroll2023). The performance encounters staged as part of the conference illuminated a deeper and more holistic perspective of those battling addiction, leading to significant shifts in the medic’s thinking and practice. In this case, Lowe’s work brought the abject to the centre. By unfolding those bodies to the conference delegates, the psychological and cultural contexts that usually propel communities to avert their gaze to avoid connecting with scenes of discomfort and despair were halted. Instead, the performance crafted by Lowe directed their focus to those scenes in a visceral collective encounter.

O’Carroll has worked in Dublin’s north inner city since 1991, treating the devastation caused by the widespread introduction of heroin in the 1980s to communities already disadvantaged by intergenerational conditions of poverty. He initially met Lowe in his capacity as her family’s GP. He reflects on how social discourse refers to the omnipresence of narcotics in all communities but challenges the underlying generalisations that thinking may suggest. ‘You’ve got cannabis and powder cocaine for well-off areas, but heroin and crack for the poor areas. More people die from drugs overdoses than road crashes in Ireland, but you wouldn’t know that from media representation’ (O’Carroll, Reference O’Carroll2023). O’Carroll brought trainee GPs to see ANU’s The Boys of Foley St (2012) directed by Lowe as part of their training, as the production addressed the emergence, distribution and class politics of heroin in the local area from the 1970s (Haughton, Reference Haughton, Tracy and Holohan2014b; Singleton, Reference Singleton2016; Hill, Reference Hill, Diamond, Varney and Amich2017). He also gave talks to the ANU team on his experience of working locally for approximately three decades during their rehearsals for The Lost O’Casey, a performance that delivers close encounters with Dublin’s inner-city communities through a handful of characters, as briefly touched upon in Section 1. Of his time working with Lowe through his medical practice and outreach, and through the development work for ANU’s productions, he concludes, ‘I think Lowe is like a witness, almost like a retrospective witness to this story that just didn’t hit the main news. And it isn’t just a story about the deaths, though that’s a big part of it, it’s the devastation that happened across the inner-city upon a background of poverty’ (2023).

O’Carroll’s confidence in Lowe’s practice is rooted in his belief that she finds a way for theatre audiences to see, or ‘confront’ as Crowe maintains (2023), certain realities of everyday life in inner city communities that for a variety of complex reasons, tend to be overlooked, marginalised, or not popular within mainstream Irish social discourse and cultural representation. The association of poverty and struggle may trigger a deeply embedded postcolonial consciousness, whereby Irish society seemed to swiftly transform into a postmodern social and cultural condition in the 1990s, which brought as many challenges as opportunities. For most of the twentieth century, Ireland was considered ‘the sick man of Europe’ (O’Carroll, Reference O’Carroll2023). Economic opportunities afforded by multinational investment in certain sectors pushed the overall national economy out of this ‘sick man’ analogy by the late 1990s; however, these statistics are not proportionate to social demographics nationally. The economics gains impacted the few, not the many. O’Carroll examines how the majority of Irish society now consider ‘the poor’ through the lens of ‘charity’. On the one hand, he surmises that some countries do not offer much scope for charity and consequently, it is better to have something than nothing. On the other hand, he argues that charity is not an accurate methodology for confronting ongoing structural inequality, and most problematically, it ‘dehumanizes and blames people, says you’re at fault, its your problem. It’s well intentioned, but that’s the thesis underneath it. She [Lowe] challenges that and brings a richness of inner-city life, the richness of their experience’ (Reference O’Carroll2023).

Lowe understands the various conditions that create poverty both as a result of her own childhood experiences and from her professional encounters. Her early career in theatre includes working with vulnerable women in the Women’s Resource Centre established in 2003 in Ballymun, an outer suburb of north Dublin, previously examined in Section 1. Details of Lowe’s theatre classes in the Centre demonstrate how in this pedagogical context performance became a safe space for creativity, expression, as well as the development of community and confidence among the women. These women had faced various and multiple challenges in their lives, including challenges pervasive in the communities in which they resided. Motherhood, without sufficient supports, and economic disadvantage often dominated their life experiences. Lowe recalls from another workshop in Dublin that she ran in the late 1990s that one woman asked her to review some games and activities with her after class, so that she could perform them again at home with her children (Lowe, Reference Lowe2020). Lowe was happy to assist. As time progressed, other women in the class confided that this woman lived alone and her children were under the care of social services. Lowe realised this was not of importance in their shared space (Lowe, Reference Lowe2020). Lowe continued to discuss games and activities she could use with her children in future conversations. Lowe stresses that in a context such as this what is important is helping that woman become the mother she wants to be, regardless of her immediate circumstances. The ability to talk, to tell, to share, and to imagine: Lowe understood that these were the skills and strategies women needed to survive.

While much of Lowe’s practice is dedicated to unfolding marginalised bodies to tell their own stories, this study does not comfortably situate Lowe as part of a momentum captured by Dani Snyder Young in Theatre of Good Intentions (Reference Snyder-Young2013). Snyder Young’s study examines a cohort of ‘artists and scholars [who] operate from a fundamental, utopian desire for theatre to make social change’ (p. 2). Lowe’s theatre does not necessarily possess roots in utopian desire from the development and production work I have experienced. Her roots are points of injustice in specific historical events and figures which continue to impact the present moment. While there are parallels with Lowe and indeed ANU’s work in some of the underlying principles of Applied Theatre as Snyder Young sets out, such as the ‘“subversive potential” to “threaten the status quo” (Lev-Aladgem, 2010: 13), or “make social structures, power relations, and individual habitus visible, and at the same time provide tools to facilitate change“ (Osterlind, 2008: 71)’ (p. 2), Lowe’s practice relishes staging complexities and contradictions where possible. In so doing, her work questions whether any form of certainty regarding historical relationships and power structures can be identified, much less transformed.

Lowe continued this work as a drama facilitator in Dublin prisons Wheatfield and Mountjoy throughout the late 1990s, working for the pre- and post-release prison services supported by the Department of Justice, in addition to delivering workshops at various resource centres. Though the working environment could be tough and tense, Lowe recounts that ‘my accent saved me. I wasn’t a prison officer, and I wasn’t a traditional type of teacher’ (Lowe, Reference Lowe2024). Throughout these experiences, the fundamental elements of Lowe’s dramaturgy become formed and cemented: a process-led approach, staging or ‘unfolding’ the body, and, the practice of care in developing work with communities, not about them. From this period, Lowe has the creative DNA for ‘Nannie’ in The Lost O’Casey, a fitting return of O’Casey’s character, informed by his own context of childhood poverty and economic struggle. O’Casey put the stories of the struggling north inner-city centre stage at the Abbey Theatre a century before Lowe, yet between the emergence of Nannie in the O’Casey play Nannie’s Night Out from 1924, and Lowe’s Nannie from 2018, the state(s) of Ireland are socially, economically, politically, and culturally transformed and incomparable. Regardless, Nannie remains. These seismic shifts include:

- The Dublin Lockout (1913)

- the Easter Rising (1916)

- the War of Independence (1919)

- the Civil War (1920–1921)

- the partition of Ireland into the 26-county Irish Free State and 6-county north of Ireland/Northern Irish state (1921–1922)

- the Republic of Ireland (1937–1939)

- the ‘Troubles’ in the north of Ireland (1968–1998)

- the ‘Celtic Tiger’ economic boom (1996–2007)

- the Citizenship Referendum (2004)

- the EU-IMF Bailout (2010)

- the Marriage Referendum legalising gay marriage (2015)

- the Repeal the 8th Referendum legalising termination of pregnancy (2018)

Nannie’s world remains, her challenges remain, and her vulnerability remains. How can a country change so radically in terms of its political governance and civic infrastructure, ideological influence, economic fortune, social and cultural expression, and yet for some people, not change at all?

2.2 Lowe, Kavanagh, and Artistic Process: ‘How Do You Catch a Dream?’

‘It’s like a poem that’s written backwards, and then you read it by the end’ (Kavanagh, Reference Kavanagh2024), Kavanagh reflects on Lowe’s process in the rehearsal room. Kavanagh is a founding member of the ANU ensemble, meeting Lowe following the conclusion of the 2009 Dublin Fringe Festival in which they both had work programmed. Kavanagh’s play Black Bessie is a one-woman show she wrote and performed in, telling the story of a nomadic sculpture woman who the audience are intended to ‘find’ and be with for a time, but ultimately leave her. Staged at Merrion Square Park, the park rangers told Kavanagh they find women like Black Bessie regularly. In Kavanagh’s piece, this woman has been sculpted by forces of church and state in Ireland. She is no longer tethered to the infrastructure of mainstream society but instead keeps her body connected to grass, soil, and the expansiveness of outside spaces. Black Bessie is deeply informed by Kavanagh’s training in fine art and sculpture from the National College of Art and Design (NCAD) in Dublin. Similar to Boss, her creative roots are in art disciplines initially, later applied to performance, and her methods for rehearsing her roles include sketching and drawing throughout the development period (Wakefires rehearsal notes, Haughton, Reference Haughton2022; Hammam rehearsal notes, Haughton, Reference Haughton2023). Further training in performance and playwriting connected her to the multifaceted shape that live performance can inhabit, with Kavanagh’s particular focus distilled to strategies of embodiment, aligning with core tenets of Lowe’s practice. Her instincts for audience connection chime directly with Lowe’s and those of Boss. For Kavanagh, ‘communion with the audience’ (Reference Boss2024) is paramount in how they conceive of and construct performance encounters.

Lowe had directed Basin for the 2009 Dublin Fringe festival, programmed at the same time as Black Bessie, and so neither artist managed to meet or see each other’s work. Basin was Lowe’s first production to utilise elements of her personal life rather than another individual’s or community’s. Exploring the space of Dublin’s Blessington St. Basin reservoir which supplied water to the north city, it is also the place where her father was warden and where Lowe’s family lived for a time. From this space of her childhood home, one can identify that Lowe was exposed to the layering of stories on place at a formative stage in her youth. Furthermore, this particular homeplace was a point of intersection between her private familial space, and the public space and civic requirements of Dublin city. Thus, one might conclude that space for Lowe is inherently a layering of experiences and legacies, and moreover, reflects a spectrum of personal and communal belonging. In creating Basin, Lowe was ‘interested in the palimpsest of life that informs the “soul” of the reservoir’ according to theatre critic Sara Keating (Reference Keating2009). Keating considers Lowe’s emerging relationship with sites of performance at this time, suggesting ‘Choosing to perform plays in cramped derelict flats or aboard moving buses, you could say that she relishes throwing the impossible her way’ (Reference Keating2009). Through the experience of making Basin, Lowe unpacks ANU’s process of critically analysing space and site-specificity to keenly distinguish their interpretation from other artists or companies who operate outside of traditional theatre spaces yet do not operate from a parallel departure point of engaging with layered histories embedded in the site of performance. Lowe reveals:

So it’s not just a case of reflecting my family’s memories but everything else that we discovered: whether that’s how the reservoir was built in the late 1700s to give water to the whole of Dublin, or that the Jameson Distillery was once located here, or that the gate lodge was a brothel, or that James Joyce wrote part of Ulysses on a bench in the park. And then there have been the experience of the locals, who have been looking at us for the last few weeks wondering what we were doing, and then offering their own histories and memories, appearing with photographs and their own stories for us; how each of them feel ownership of the space in a different way.

From this 2009 Dublin Fringe Festival programme, Kavanagh and Lowe are both centring their performance narratives and strategies on the physical environment of their home city, revealing how certain bodies, politics, and experiences are entangled in society’s shifting relationships with those sites. Though neither had sufficient financial resources in 2009 to produce their work in a theatre building, established theatre buildings would not have suited their creative intentions regardless of whether further funding had materialised. Elements of postmodern and postdramatic thinking and strategies can also be identified through both works, as performance scholar Sara Jane Bails details, which address ‘the limitations posed by linguistic structures and traditional narrative conventions that now seem[ed] outmoded […] Theatre language, itself a field of knowledge production, could be made to express intensities and mood-states rather than service the development of character and linear plot on stage’ (Bails, p. xix). Neither Black Bessie nor Basin serviced the development of character or linear plot on stage, but instead, staged encounters to enable audiences glimpse narratives of the city less well-known, unveiling the rich tapestry of connections between site, story, and performance, like a prologue to the ‘NOW-THEN-NOW’ approach ANU formalises not long after. ‘NOW-THEN-NOW’ became constituted as ANU’s leading dramaturgy through conversation led by founding member and performer Robbie O’Connor. In development for World End’s Lane (2010, 2011) set at the start of the twentieth century, ANU struggled with the period costume and the language of the time. They realised the creative blockage they were encountering was caused by the fixity in time, and that their characters and actions needed to journey with the audience between the past and present in a type of collision.

Boss, Kavanagh, Lowe, and O’Connor are ANU’s founding members, and their meeting became realised through a development day organised by Dublin Fringe on conclusion of the 2009 Festival. This occurred at The Lab, a multidisciplinary city centre arts space located near ‘the Monto’ where Lowe was raised and where ANU’s first major cycle of work was staged (2010–2014; Singleton, Reference Singleton2016). Kavanagh walked into a room and saw the early seeds of ANU’s Monto Cycle mapped out on four walls: (1) images from Debbie’s family’s Romany tradition: Debbie is Lowe’s best friend from childhood, now married to Boss; (2) photos of Amanda Coogan’s work: Coogan is an internationally acclaimed Irish performance artist, trained by and collaborator of Marina Abramović who mentored Lowe in the early stages of her career; (3) drawings of Irishman Frank Duff (1889–1980): a civil servant and founder of the Legion of Mary, a Catholic organisation involved in establishing Mother and Baby Institutions in Ireland; (4) the work of Emma O’Kane: leading Irish dance artist (1977–2021) and Robin Wilson, internationally acclaimed lighting designer. In this memory, Kavanagh connects the core ideas that inspired the aesthetic and social roots of ANU: (1) exploring the diversity of communities that make up contemporary Dublin; (2) working across artistic disciplines to see what possibilities arise, in particular, through visual and performance art, dance, installation and theatrical performance and (3) examining the impact of the founding ideas that informed the creation of a conservative Catholic Irish State almost a century ago, following an embittered civil war between pro- and anti-Treaty forces (Anglo-Irish Treaty 1921–1922), further examined in the case studies The Wakefires (2022) and Hammam (2023–2024). Lowe and Boss discussed their plans to undertake a 100-year history of ‘the Monto’ as one production, later becoming four interconnected productions, ‘The Monto Cycle’, richly analysed in Singleton’s Reference Singleton2016 monograph of the same name. During this meeting Lowe tells Kavanagh, ‘I’m not sure what its going to be’, signalling an open approach that Kavanagh felt motivated by (Reference Kavanagh2024).

‘What was the language in the room’, Kavanagh ponders regarding her own reflections of this time as they began to develop World End’s Lane, the first iteration of the ‘The Monto Cycle’ premiered in Dublin Fringe Festival in 2010 and restaged in Dublin Theatre Festival in 2011, alongside ANU’s second iteration, Laundry (2011). She recalls that they organically spoke a shared language regarding performance, aesthetic, and connection with audiences. This sense of artistic connection led them to a develop a shorthand in their rehearsal and development work, which Kavanagh asserts includes a sense of understanding where they are going, though not necessarily a language that can literally be captured or explained in words. ‘How do you catch a dream’? (2024) she asks rhetorically. To provide a stronger sense of clarity of their shared energies and intentions in the work, she turns to the significance of the historical figures they foreground, beginning with Honour Bright in World’s End Lane. Bright, like Nannie, epitomises the figures from that past that Lowe finds and revives for the present. World End’s Lane explored the ‘Monto’ area, which housed ‘almost 6,000 prostitutes [in the] largest and most prolific red-light district in Europe, up until it’s dramatic closure in one night by one man (Frank Duff, founder of the Legion of Mary) on 12th March 1925’ (World End’s Lane, ANU). Lowe recognises the gaps in official history, using ANU’s productions to return these figures to public consciousness, acutely showcasing their suffering and strength, the contexts in which they lived, how their existence challenge the status quo, and, indeed, how they were punished for this by those with access to more power and privilege, at times, with impunity.