1 Introduction

The Challenges of Multilateral Governance

In 2015, the global community achieved two significant milestones in multilateralism: the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Paris Agreement aims to limit the increase in global temperature to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with a preference for staying below 1.5°C (UNFCCC, 2015). The 2030 Agenda is centred around seventeen sustainable development goals (SDGs), designed to address the three pillars of sustainability: social, environmental, and economic (United Nations, 2015).Footnote 1

Despite these notable accomplishments, global cooperation is facing tremendous pressure. The progress of multilateral climate negotiations towards implementing the Paris Agreement has been frustratingly slow. Other multilateral approaches dealing with global environmental challenges are also progressing at a sluggish pace, such as the global biodiversity regime or non-existent altogether, as in the case of ocean acidification.

At the same time, multilateral trade negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) have encountered significant obstacles. While there have been some recent breakthroughs,Footnote 2 it has been nearly three decades since the conclusion of the last major multilateral trade agreement. The WTO has become a victim of its own success (Reference BaldwinBaldwin, 2010), as the focus shifted from reducing tariffs to aligning domestic regulatory approaches (Reference HoekmanHoekman, 2014). With an increasing number of heterogeneous members, reaching a consensus on multilateral solutions has become more challenging, resulting in the ‘legislative gridlock’ of the WTO (Reference NarlikarNarlikar, 2010). The Doha Round negotiations, which aimed to address the concerns of developing countries, reached an impasse with no resolution in sight. Furthermore, the rise of new economic powers such as China and India has made achieving global consensus even more challenging than before (Reference Hale, Held and YoungHale et al., 2013). Populism, trade wars, and ongoing military conflicts continue to undermine global economic cooperation.

Nevertheless, policy actions are necessary. Human interference in the Earth’s system has reached an unprecedented scale, posing enormous challenges for scientists and policymakers that call for global cooperation and a shift towards sustainability. We are now in the Anthropocene, a new geological age in which humans are altering the very Earth system upon which our livelihoods depend. Global economic governance cannot remain stagnant in the face of these existential challenges.

The Importance of Studying the Trade and Environment Interplay

This Element explores the complex and contested relationship between trade governance and environmental governance by analysing its drivers and effects. Understanding this relationship is critical for several reasons: First, international trade is integral to the modern world economy. We cannot understand our patterns of resource extraction and consumption without examining how and why these resources travel across borders. The value of exports has increased more than forty times since 1913. This increase was even more pronounced than the global production growth. Not only do we produce more goods but we also export a greater share of what we produce.

Second, international trade has significant environmental impacts. For instance, carbon emissions embodied in trade constitute a large and growing share of global emissions (Reference SatoSato, 2014). The harmful effects of air pollution on Chinese residents, for example, are primarily associated with exports to the United States (US) (Reference Wiedmann and LenzenWiedmann & Lenzen, 2018). Moreover, between 29 per cent and 39 per cent of deforestation-related emissions are driven by international trade, mainly in beef and oilseeds like palm oil (Reference Pendrill, Persson and GodarPendrill et al., 2019). The United Kingdom (UK), Germany, France, Italy, and Japan ‘imported’ more than 90 per cent of their national deforestation footprints from abroad between 2001 and 2015, of which between 46 per cent and 57 per cent were from tropical forests (Reference Hoang and KanemotoHoang & Kanemoto, 2021). Thus, trade is highly relevant from an environmental perspective. The stakes are particularly high for developing countries because the harmful effects of trade are concentrated in the Global South.

Third, trade can contribute to addressing environmental problems (for more details, see Section 2). Trade can enable more resource-efficient production, the spread of environmental standards, and the diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies. Given these mixed effects, it is not surprising that the relationship between trade and the environment remains controversial. Debates on the positive and negative effects of trade on the environment were particularly heated during the negotiations for the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the US and the European Union (EU) and the negotiations between the EU and the Mercosur countries, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

Fourth, the design of trade policies matters for environmental protection. In some cases, trade policies have been poorly designed. For example, import tariffs and nontariff barriers tend to be lower in dirty industries than in clean industries, creating a global implicit subsidy for CO2 emissions (Reference ShapiroShapiro, 2021). If countries applied similar trade policies to clean and dirty goods, global CO2 emissions would decrease by 1 per cent to 5 per cent, which is comparable to the estimated effects of the European Union Emissions Trading System (Reference ShapiroShapiro, 2021). Conversely, well-designed preferential trade agreements (PTAs) can have beneficial environmental effects. For example, PTAs with environmental provisions can increase the export of environmental goods by 17 per cent (Reference Brandi, Schwab, Berger and MorinBrandi et al., 2020) and reduce forest losses by an average of approximately 23 per cent (Reference Abman, Lundberg and RutaAbman et al., 2021).

Finally, analysing the interplay between trade and the environment is vital in the context of the modern global governance system, which is characterized by a complex web of institutions with overlapping mandates. The age of siloed global governance is over. Today, international agreements do not develop in isolation from one another, as was initially assumed by the earlier regime theory and some of the treaty design literature. Instead, institutions interact with each other and are typically embedded in a broader regime complex (Reference Raustiala and VictorRaustiala & Victor, 2004). The interface between international regimes must be addressed directly to tackle current urgent global challenges with limited resources. Previous research on the interlinkages between trade and the environment has primarily focused on the WTO. This Element contributes to a more recent generation of scholarship that considers novel ways to link trade and the environment in bilateral and regional trade agreements.

Looking at Preferential Trade Agreements and Their Environmental Provisions

In this Element, we focus on exploring the potential contribution of PTAs to global environmental governance. Since 1947, over 770 PTAs have been concluded, with increasingly diverse and far-reaching environmental provisions. Although missed opportunities and harmful provisions still exist, numerous environmental provisions within PTAs have great potential. Some provisions promote the implementation of environmental treaties, facilitate civil society participation, and require the transfer of environmental technologies to developing countries. These provisions cover a wide range of environmental issues, such as limiting deforestation, protecting fish stocks, and mitigating CO2 emissions. Additionally, some PTAs provide for the use of their primary dispute settlement mechanisms, which can ultimately lead to trade sanctions in cases of alleged non-compliance with environmental provisions.

The proliferation of PTAs and their environmental provisions necessitates new research on the trade-environment interface. New data and methods, including detailed content analysis across multiple treaties, are needed to explain the interlinkages and understand if and how PTAs’ environmental provisions can help tackle global environmental challenges.

While acknowledging the challenges and negative externalities resulting from tensions between the trade and environmental regimes, this Element asks a different question: How can trade governance be part of the solution and strengthen environmental governance? Our investigation aims to determine whether, why, and how PTAs can contribute to environmental protection.

Overall, this Element demonstrates that well-designed environmental provisions within trade agreements can improve environmental protection and promote the SDGs.

The Element addresses four key questions that are explored throughout its sections:

1. How does global governance at the trade-environment interface contribute to environmental performance? The Element demonstrates that global governance at the trade-environment interface can mitigate the negative externalities of trade and increase positive externalities. This indicates that international institutions really do matter, which is a useful reminder in these troubled times as they are increasingly being attacked by nationalists and populists, as well as cynical and disillusioned activists.

2. To what extent does governance at the trade-environment interface lead to trade-offs between the economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable development? While governing the trade-environment interface may create trade-offs, it can also create synergies across the different dimensions of sustainable development. For example, environmental provisions that reduce trade barriers for environmental goods can generate economic and environmental benefits.

3. To what extent do high-income countries take advantage of power imbalances to impose their views on the trade-environment interface? The Element recognizes the power dynamics in international relations and emphasizes the need for environmental provisions to be designed in a way that considers the interests of developing countries and their most vulnerable populations.

4. As more environmental provisions are included in more trade agreements, what are the implications for the fragmented nature of trade and environment interlinkages and regime complexes? The Element acknowledges the challenges posed by the fragmentation of global governance architecture (Reference BhagwatiBhagwati, 2008; Reference BiermannBiermann, 2014; Reference YoungYoung, 2012), particularly in terms of coordination and coherence. Fragmentation also creates opportunities for innovation and adaptability (Reference AbbottAbbott, 2014; Reference FaudeFaude, 2020; Reference Gehring and FaudeGehring & Faude, 2014; Reference JinnahJinnah, 2011; Oberthür & Gehring, 2006). This Element contributes to this second line of inquiry. The inclusion of environmental provisions in PTAs provides a framework for experimenting with trade-environment interlinkages and can potentially help to overcome the stalemate in the WTO. This Element suggests that this can enhance the adaptability of the global trade system to pressing environmental challenges.

Data and Methods

This Element synthesizes our previous research on the interplay between trade and the environment. Its originality lies in the analysis of an update version of the TRade and ENvironment Database (TREND), the most comprehensive dataset of its kind.Footnote 3 The original version of TREND released in 2018 covered 670 PTAs concluded between 1947 and 2016 (Reference Morin, Dür and LechnerMorin et al., 2018b). This updated version of TREND includes over 100 additional PTAs and provides the latest insights into the content and design of these agreements.Footnote 4

Using a dataset as large and detailed as TREND offers numerous analytical benefits. It enables us to draw generalizable lessons beyond the idiosyncrasies of controversial trade agreements. Moreover, using large-n datasets makes it possible to use statistical techniques to uncover causal effects, for example, those based on panel data analysis or the quasi-experimental method of propensity score matching. Various robustness tests can be used to substantiate the empirical findings. Furthermore, large-n approaches offer an important birds-eye perspective on the issue, analysing the global governance architecture of trade and the environment across the full spectrum of PTAs (Reference Biermann, Kim, Biermann and KimBiermann & Kim, 2020).

To complement the use of quantitative approaches, this Element relies on qualitative research methods and includes insights gained from semi-structured interviews. We conducted nine interviews with trade officials and other experts, among others from the EU, the US, Chile, and New Zealand (see Annex). The interviews were conducted via telephone or video calls, transcribed, and analysed. The semi-structured interviews included several questions focusing on trade and environment interlinkage in the context of the negotiations of PTAs, their implementation, and post-agreement cooperation.

By combining these diverse research methods, we aim to provide a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the interlinkages between trade and environmental governance.

Our Contribution

In contrast to the prevailing perspective that the fragmentation of the trading system has only negative consequences (Reference BhagwatiBhagwati, 1995), our Element argues that the fragmentation of trade and environmental governance can be seen more positively and can be regarded, under certain conditions, as productive in terms of environmental protection. In some cases, the dynamism of the trade regime complex has become a leverage point for environmental protection. Therefore, this Element offers a foundation for enhancing the readiness of current trade governance systems to address urgent global environmental challenges and Earth system transformations such as climate change and biodiversity loss.

This argument is significant and relevant, because the relationship between trade and the environment has become increasingly important. The issue of whether and how to link trade and the environment in PTAs is a highly debated topic in both research and policy circles. For instance, major disputes have recently arisen in the context of the EU-Mercosur trade agreement and the WTO agenda on trade and the environment. Furthermore, the introduction of a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) by the EU – a tariff on carbon-intensive EU imports – has sparked further contentious discussions about trade and environmental linkages. Drawing on insights from law, economics, and political science, this Element provides a comprehensive investigation of the governance of the trade-environment interface in the light of the proliferation of environmental provisions in PTAs.

This Element contributes to Earth System Governance (ESG) research and the Science and Implementation plan. Above all, it relates to the ESG research lens ‘Architecture and Agency’, which focuses on ‘understanding the institutional frameworks and actors implicated in earth system governance and how these institutions and actors resist or respond to change and evolve over time’ (Reference Burch, Gupta and InoueBurch et al., 2019). Consistent with the ESG research plan, this Element places a special emphasis on governance architecture as ‘the interlocking web of widely shared principles, institutions, and practices that shape decisions at all levels in a given area of earth system governance’ (Reference Biermann, Betsill and GuptaBiermann et al., 2009a, p. 31). This Element contributes to the discussion on three topics that are particularly salient in the context of architecture issues: institutional interlinkages, regime complexity, and fragmentation.

Roadmap for the Element

The Element is organized as follows. Section 2 examines the proliferation of PTAs and their environmental provisions in the context of institutional interlinkages, regime complexes, and fragmentation. Section 3 introduces trade and environmental interlinkages, explores the diverse environmental provisions found in PTAs, and discusses their compliance and enforcement mechanisms. Section 4 investigates the various drivers of PTA environmental provisions, which are becoming increasingly frequent and diverse. Section 5 explores the important North-South dynamics of PTA negotiations and the inclusion of environmental provisions. Section 6 examines the global spread of environmental provisions in PTAs. Section 7 analyses the effects of environmental provisions in PTAs from both environmental and economic perspectives, examining the synergies and trade-offs between different dimensions of sustainable development. Section 8 goes beyond the bilateral and regional levels and considers broader implications for greening trade governance at the multilateral level. Section 9 summarizes the potential benefits and pitfalls of environmental provisions in trade agreements and presents ten evidence-based policy recommendations.

Overall, this Element provides a comprehensive and nuanced analysis of the relationship between trade and the environment in the context of PTAs, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative research methods to offer insights into the drivers, effects, and implications of environmental provisions in trade agreements.

2 Trade and Environment: Interlinkages, Complexity, and Fragmentation

In the early 2000s, the global governance literature shifted its attention from distinct international institutions to the growing interlinkages between them (Reference Raustiala and VictorRaustiala & Victor, 2004). As new interrelated issues came to the forefront, numerous institutions were created, leading to a progressively crowded global governance landscape. The resulting interconnections generated larger complexes of interacting institutions. Ultimately, they gave rise to governance architectures, that is, ‘overarching system of public and private institutions, principles, norms, regulations, decision-making procedures and organizations that are valid or active in a given area of global governance’ (Reference Biermann, Kim, Biermann and KimBiermann & Kim, 2020, p. 4). The features of governance architectures are frequently characterized, among other things, in terms of their interlinkages, complexity and fragmentation (Reference Biermann, Kim, Biermann and KimBiermann & Kim, 2020). Therefore, we explore the interplay between trade and the environment by investigating interlinkages between two fragmented sets of institutions, frequently referred to as regime complexes.

Institutional Interlinkages

An increasing number of institutions have been established to address novel issues. They interact and form institutional interlinkages, that is, ‘formal or informal connections between two institutions and their associated policy processes’ (Reference Hickmann, van Asselt, Oberthür, Biermann and KimHickmann et al., 2020, p. 120).Footnote 5 The incorporation of environmental provisions into trade agreements is a typical example of institutional interlinkage politics.

In recent decades, institutions and their interactions have mushroomed across global governance architectures. Typologies of institutional interlinkages have also developed rapidly (e.g., Reference StokkeStokke, 2000, Reference Stokke2001; Reference YoungYoung, 1996, Reference Young and Gasser2002). The literature on environmental interlinkages has largely focused on ‘utilitarian’ interlinkages (Reference StokkeStokke, 2001), which are aimed at cost reduction and efficiency. However, recent research indicates that some interlinkages can also be characterized as ‘catalytic’ (Reference Betsill, Dubash and PatersonBetsill et al., 2015; Reference HaleHale, 2020) as they are designed to facilitate action.

Interlinkages can lead to conflicts, synergies, or may be neutral (Reference Oberthür, Gehring, Oberthür and GehringOberthür & Gehring, 2006a, p. 46; Reference PulkowskiPulkowski, 2014; Reference Van Asseltvan Asselt, 2014; Reference Zelli, van Asselt, Biermann, Pattberg and ZelliZelli, 2010). Although interlinkage conflicts have been conceptualized in different ways (Reference PulkowskiPulkowski, 2014; Reference Van Asseltvan Asselt, 2014), the notion ‘remains under-explored’ (Reference Hickmann, van Asselt, Oberthür, Biermann and KimHickmann et al., 2020, p. 125). A useful distinction differentiates narrowly defined ‘norm conflicts’ from broader ‘policy conflicts’ (Reference Van Asseltvan Asselt, 2014). While norm conflicts, that is, incompatibilities between the norms of two treaties, may have some relevance in the context under consideration, we focus on policy conflicts, that is, broader tensions. We explicitly conceptualize these tensions as ‘trade-offs’. We show that two interlinked institutions may not only have different goals and be in conflict, but that achieving one institution’s goal may only be possible at the expense of the other.

Thereby, we address not only the literature on institutional interlinkages but also the concept of policy coherence, which strives to leverage synergies and minimize trade-offs (OECD, 2019). Surprisingly, synergies have received much less attention in the literature than conflicts (Reference Hickmann, van Asselt, Oberthür, Biermann and KimHickmann et al., 2020). Against this background, our Element seeks to draw attention to trade-offs and synergies in relation to trade and environment interlinkages.

While most research on trade and environment interlinkages has focused on the WTO, less attention has been paid to interlinkages in bilateral and regional PTAs, which is the focus of this Element. The majority of existing studies on trade and environment interlinkages investigate the WTO (Reference CharnovitzCharnovitz, 2007; Reference ConcaConca, 2000; Reference EckersleyEckersley, 2004; Reference JinnahJinnah, 2010, Reference Jinnah2014; Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2015; Reference NeumayerNeumayer, 2004; Reference Zelli, van Asselt, Biermann, Pattberg and ZelliZelli & van Asselt, 2010).Footnote 6 Existing scholarship on the environmental provisions of PTAs has largely focused on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and its innovative environmental side agreement (e.g., Reference GallagherGallagher, 2004; Reference Hufbauer, Esty, Orejas, Schott and RubioHufbauer, 2000). Some scholarship explores environmental provisions in US PTAs (Reference JinnahJinnah, 2011; Reference Jinnah and MorinJinnah & Morin, 2020), as well as US and EU perspectives regarding environmental content in PTAs (Reference Bastiaens and PostnikovBastiaens & Postnikov, 2017; Reference Benson, Janardhan and ReinschBenson et al., 2022; Reference Jinnah and MorgeraJinnah & Morgera, 2013; Reference Morin and RochetteMorin & Rochette, 2017). However, only a limited number of studies have assessed the environmental provisions in trade agreements across a larger number of PTAs.

Regime Complexes

The proliferation of institutional interlinkages between hundreds and thousands of organizations, agreements, and other institutions in international politics is such that it prompted the development of the concept of ‘regime complex’ (Reference AbbottAbbott, 2012; Reference Alter and MeunierAlter & Meunier, 2009; Reference Gómez-Mera, Morin, Van de Graaf, Biermann and Kim EduGómez-Mera et al., 2020; Reference Keohane and VictorKeohane & Victor, 2009; Reference Orsini, Morin and YoungOrsini et al., 2013; Reference Raustiala and VictorRaustiala & Victor, 2004). It is a ‘signature feature of twenty-first century international cooperation’ (Reference Alter and RaustialaAlter & Raustiala, 2018). A regime complex is a ‘network of three or more international regimes that relate to a common subject matter, exhibit overlapping membership, and generate substantive, normative, or operative interactions recognized as potentially problematic whether or not they are managed effectively’ (Reference Orsini, Morin and YoungOrsini et al., 2013, p. 29).

In comparison to institutional interlinkages, the concept of regime complex captures the myriad connections between three or more institutions within the context of their broader governance at a more systemic analytical level (Reference Hickmann, van Asselt, Oberthür, Biermann and KimHickmann et al., 2020). As a result of the growing interest in regime complexes, complexity has become a major approach for investigating global governance architectures (Reference Duit, Galaz, Eckerberg and EbbessonDuit et al., 2020; Oberthür & Stokke, 2011; Reference Pattberg and ZelliPattberg & Zelli, 2016).

Fragmentation

Fragmentation is a key feature of global governance architectures and can be defined as the proliferation of actors, institutions, and instruments, which can result in a lack of coordination and coherence among them (Reference Biermann, Pattberg, Van Asselt and ZelliBiermann et al., 2009b). Research on fragmentation investigates global governance architectures from the perspective of integration and decentralization (Reference Biermann, Pattberg, Van Asselt and ZelliBiermann et al., 2009b; Reference Keohane and VictorKeohane &Victor, 2011; Reference Zelli and van AsseltZelli & van Asselt, 2013). For instance, it has shed light on how state actors enter partnerships with non-state actors (Reference PattbergPattberg, 2010; Reference Pattberg and WiderbergPattberg & Widerberg, 2016) and assessed the increasing role of private governance such as certification (Reference Auld, Renckens and CashoreAuld et al., 2015).

More recently, researchers have begun to study potential responses to fragmented governance systems (Reference Van Asselt and Zellivan Asselt & Zelli, 2014). In the context of the question of how fragmentation can be managed, particular attention is given to the interactions between diverse regimes (Reference Jinnah and LindsayJinnah & Lindsay, 2016; Reference Van Asseltvan Asselt, 2014), including those that govern trade and the environment. Possible responses to the fragmentation of governance architectures and their complexity include policy integration, which aims at including environmental goals into non-environmental policy realms, or interplay management, which seeks to restrict conflicts generated by institutional interlinkages (Reference Biermann, Kim, Biermann and KimBiermann & Kim, 2020).

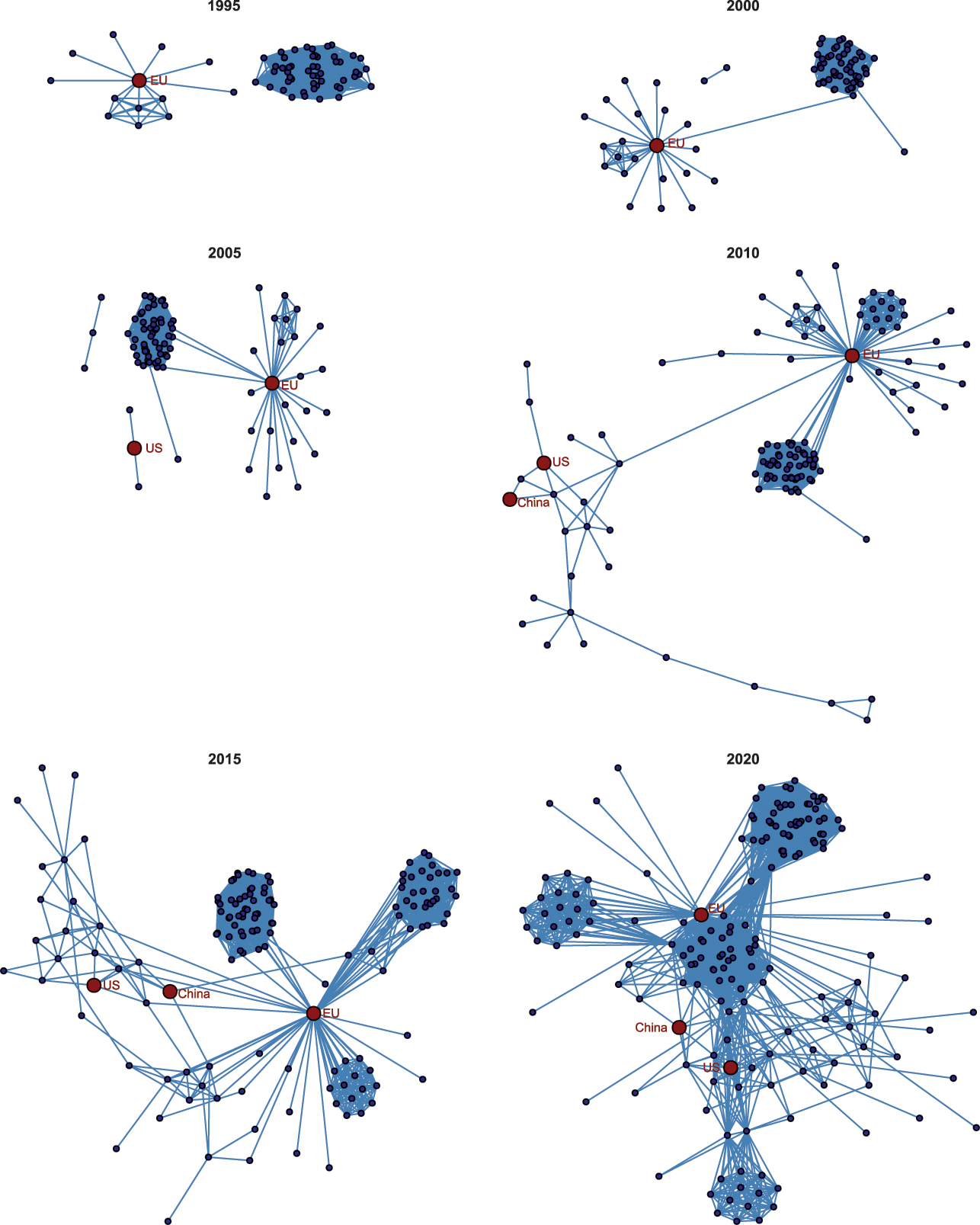

Introducing the Trade Regime Complex

The trade regime complex has grown rapidly in recent years, and is still expanding. An increasing number of actors and institutions are interested in governing trade-relevant questions, which has generated a complex governance architecture. A dense regime complex for trade has emerged, featuring numerous overlaps between inter- and transnational institutions. The complex is growing in three ways with regard to: institutions, the issues addressed (including the environment), and geography (developing countries and rising powers are increasingly active players) (Reference Meunier, Morin, Morin, Novotná, Ponjaert and TelMeunier & Morin, 2015).

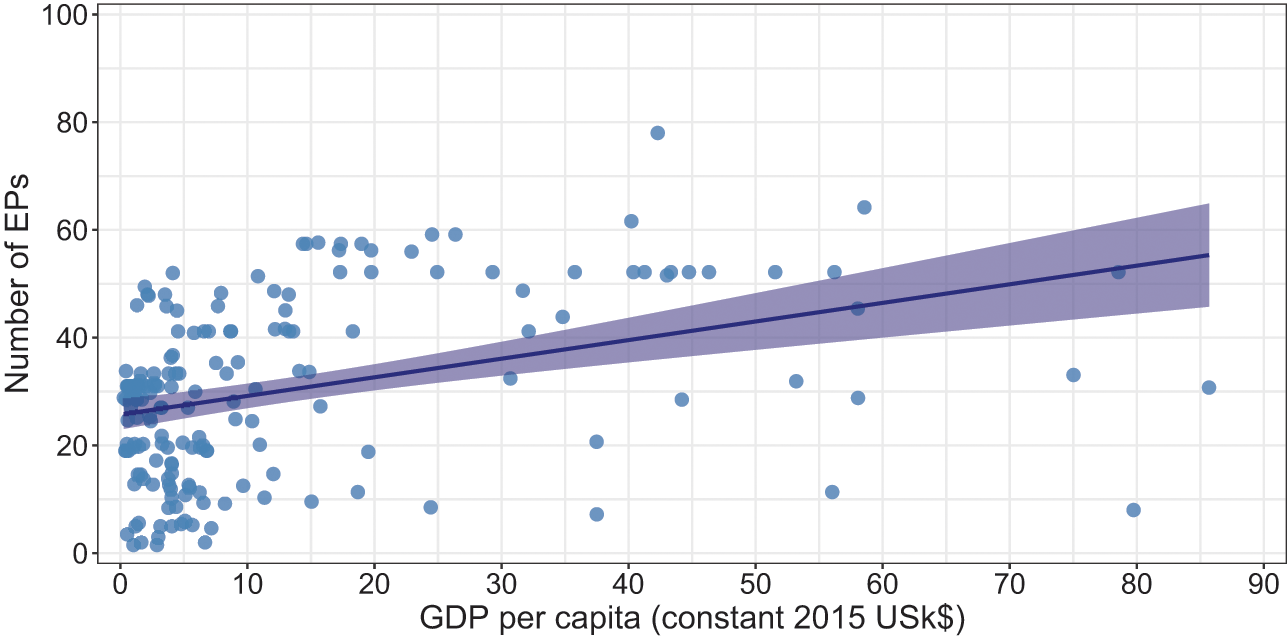

First, the trade regime complex is expanding on an institutional level. Given the deadlock in multilateral trade negotiations, negotiators are increasingly turning to bilateral and regional trade agreements. More than 700 PTAs have been concluded since 1947. The mushrooming of PTAs can be characterized as ‘the main change to the international trading system since the mid-1990s’ (Reference Baccini and DürBaccini & Dür, 2015, p. 617). As shown in Figure 1, virtually all countries have concluded more than ten PTAs, including the US, China, India, Japan, and most African countries. Moreover, multiple countries are parties to more than fifty PTAs, including Brazil and Mexico. Some countries, particularly in Europe, are party to seventy or more (up to ninety) trade agreements.

Figure 1 World map with number of PTAs per country

The term PTA covers different types of agreements, including sector agreements, free trade areas, custom unions, and common markets. A sectoral agreement is limited to a particular trade issue or sector, such as trade in services or in the automobile sector. A free trade area eliminates tariffs between two or more countries and can also reduce non-tariff barriers to trade on goods and services (e.g., the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership or RCEP). A customs union is a special type of free trade area in which the members of the agreement agree to apply a common set of external tariffs to imports from the rest of the world (e.g., the Southern Common Market, MERCOSUR). A common market, in turn, is even more integrated: it not only offers the free movement of goods and services but also the free movement of labour and capital (e.g., the EU). Following the DESTA Project (Reference Dür, Baccini and ElsigDür et al., 2014), the PTAs included in the TREND dataset may be sectoral agreements, free-trade agreements, customs unions, or economic unions.

In addition to PTAs, other institutional forms have developed rapidly in the trade regime complex, including plurilateral agreements (e.g., the Government Procurement Agreement), fora for regulatory agencies (e.g., the International Competition Network), collaboration across intergovernmental organizations (e.g., the Standards and Trade Development Facility) and across private organizations (e.g., the International Accounting Standards Board) (Reference BrandiBrandi, 2017).

Second, the trade complex covers an increasing number of issues. It addresses ‘WTO-extra’ issues, such as tax evasion, which were originally not negotiated in the WTO (Reference BaldwinBaldwin, 2014; Reference Horn, Mavroidis and SapirHorn et al., 2010). As these issues are now tackled by a growing number of trade-related initiatives, the scope of the trade regime complex continues to expand.

Traditionally, PTAs aimed to eliminate tariffs, but they now incorporate non-economic policy areas such as the environment. The content of PTAs is gradually diversifying. This can be illustrated by a measure of their depth, which depicts the extent of tariff liberalization and cooperation in the areas of services trade, investments, public procurement, competition, and intellectual property rights (Reference Dür, Baccini and ElsigDür et al., 2014).Footnote 7 As shown in Figure 2, the average depth of PTAs has risen steadily over the past four decades, indicating the ever-more far-reaching content of PTAs. At the same time, while the average PTA has deepened, some agreements remain shallow. For example, the EU and NAFTA are much deeper agreements than the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). This heterogeneity is a crucial dimension of the trade agreement landscape.

Figure 2 Bar chart with number of PTAs per year and average score of DESTA depth

Third, the trade regime complex is growing geographically. Until the 1990s, only a few countries have been negotiating PTA. However, nowadays, many countries are simultaneously involved in trade negotiations worldwide. The trade complex is an expanding system that can be analysed as a whole (Reference Meunier, Morin, Morin, Novotná, Ponjaert and TelMeunier & Morin, 2015; Reference Pauwelyn, Alschner, Dür and ElsigPauwelyn & Alschner, 2015).

Implications of Fragmentation and Complexity?

Scholars and decision-makers are concerned that the mushrooming of PTAs will undermine the trade regime, by making the trade system ever more fragmented (Reference Hoekman and SabelHoeckman & Sabel, 2019), with the so-called spaghetti bowl of PTAs (Reference BhagwatiBhagwati, 1995, p. 5). Critics argue that PTAs, like termites, eat ‘away at the multilateral trading system relentlessly’ (Reference BhagwatiBhagwati, 2008, p. vii). However, PTAs have circumvented this WTO deadlock. They enable subsets of WTO members to find consensus on new trade rules where the entire community of WTO members has failed. Preferential trade agreements allow legislative progress and may have the capacity to help the trade order adapt to shifting contexts. Therefore, PTAs can strengthen resilience (Reference FaudeFaude, 2020). As we will argue in Section 8, PTAs can also help to promote agreement on new trade rules at the multilateral level, as they can provide a laboratory for experimenting with new rules that can eventually be adopted more widely.

The question of how to evaluate the growing density of overlapping institutions from a normative point of view has received little attention thus far (Reference Hickmann, van Asselt, Oberthür, Biermann and KimHickmann et al., 2020). Regime complexes have both positive and negative effects. They can create winners and losers (Reference Alter and RaustialaAlter & Raustiala, 2018). A regime complex offers substantial benefits; for example, it can enable experimentation, help overcome gridlock, balance deviating societal interests, allow for flexibility, favour innovation, adapt to a changing environment, and facilitate cost and burden sharing (Reference De Búrca, Keohane and SabelDe Búrca et al., 2014; Reference FaudeFaude, 2020; Reference Faude and Groβe-KreulFaude & Große-Kreul, 2020; Reference Gehring and FaudeGehring & Faude, 2013; Reference PauwelynPauwelyn, 2014). On the other hand, complex systems involving multiple institutions can also generate challenges: duplication and confusion, substantial knowledge and capacity are required, and institutional interactions must be managed (Reference Biermann, Pattberg, Van Asselt and ZelliBiermann et al., 2009b). This tends to privilege those with greater resources (Reference Alter and RaustialaAlter & Raustiala, 2018).

Overall, the impact of fragmentation and complexity on global governance is a topic of debate among scholars (for a comprehensive overview, refer to Reference Biermann, Kim, Biermann and KimBiermann & Kim, 2020). Some scholars hold a pessimistic view of fragmented governance structures due to the difficulties of achieving coordination and coherence across various institutions (Reference BiermannBiermann, 2014; Reference YoungYoung, 2012). However, other scholars are more optimistic about the proliferation of regime complexes and their potential outcomes. They argue that such structures can be more adaptable across time and issue areas than more integrated architectures (Reference FaudeFaude, 2020; Reference Keohane and VictorKeohane & Victor, 2011).

In this Element, we substantiate the optimistic perspective while recognizing the negative aspects of fragmentation. As we will demonstrate, the fragmentation of regime complexes has the potential to enhance the resilience and adaptability of global governance, and can act as a catalyst for environmental protection, provided that it is navigated with caution.

3 Linking Trade and the Environment in PTAs

The relationship between international trade and environmental protection is complex and multi-faceted. There is an ongoing debate, both theoretically and empirically, about whether trade contributes to environmental degradation or helps address environmental challenges. This section aims to outline the current controversies surrounding the relationship between trade and the environment as well as recent trends in the governance of this interplay.Footnote 8 Additionally, we highlight the growing diversity of trade agreements and the numerous environmental provisions they contain, along with their various compliance mechanisms.

Trade: Good or Bad for the Environment?

Based on the economic theory of comparative advantage (Reference RicardoRicardo, 1817), some economists argue that international trade increases countries’ overall welfare, which in turn enhances environmental protection and provides more affordable access to environmentally friendly goods and services (Reference BhagwatiBhagwati, 1993). Others describe the relationship between trade and the environment as divergent (Reference ConcaConca, 2000; Reference EstyEsty, 1994). There are serious concerns that more international trade implies more transport and production, and thus, higher resource use and heavier environmental degradation (Reference DalyDaly, 1993).

In 1991, Grossman and Krueger published their seminal paper on how international trade can impact the environment by affecting the scale of economic activity (scale effect), composition of production across industries (composition effect), and emission intensity of individual industries (technique effect). A remarkable discovery was made based on their empirical analysis: international trade may not necessarily have a negative impact on the environment (Reference Grossman and KruegerGrossman & Krueger, 1991).Footnote 9

Although there have been considerable strides in understanding the relationship between trade and the environment by now, there is still a dearth of empirical evidence concerning this interplay and the link between international trade and environmental consequences remains contested (for recent reviews, see Reference Cherniwchan, Copeland and TaylorCherniwchan et al., 2017; Reference Cherniwchan and TaylorCherniwchan & Taylor, 2022). Some studies have found that trade is detrimental to the environment. For example, evidence suggests that international trade is a major source of air pollution in the shipping sector (Reference GallagherGallagher, 2005). Other studies find that trade is good for the environment, for example, by providing evidence that exporting to the EU and the US strengthens environmental performance in developing countries because the consumer demand for environmentally friendly goods and services in the EU and the US is greater than in developing countries (Reference GamsoGamso, 2017). While some scholars argue that international trade leads to a race to the lowest environmental standards (Reference DalyDaly, 1993), others illustrate that trade can induce the spread of higher environmental standards (Reference VogelVogel, 2009).

Given these ambiguous findings regarding international trade and environmental protection, it is unclear how their interplay affects the environment. Recent research on the trade-environment interface underlines the importance of the design of trade policies in this regard (Reference Brandi, Schwab, Berger and MorinBrandi et al., 2020; Reference ShapiroShapiro, 2021). It is also unclear how international trade affects sustainable development more broadly. It is frequently argued that trade can be a powerful tool for achieving the SDGs (e.g., Reference Bellmann and TippingBellmann & Tipping, 2015). Trade can enhance productivity, generate higher incomes, increase growth, and help alleviate poverty (Reference BacciniBaccini, 2019; Reference Baier and BergstrandBaier & Bergstrand, 2007; Reference Winters and MartuscelliWinters & Martuscelli, 2014). Thus, reducing trade barriers can contribute to achieving several SDGs, including those related to poverty (SDG 1) and growth (SDG 8). Simultaneously, reducing trade barriers always generates winners and losers, and tends to increase inequalities (which contradicts SDG 10). If trade-offs exist between trade and environmental protection, liberalizing trade could undermine the environmental dimensions of sustainable development, making it harder to achieve goals that aim to minimize the use of natural resources (SDG 12) or protect ecosystems, such as forests (SDG 15).

In summary, there are multiple theoretical perspectives on the debate about trade and the environment. However, additional empirical evidence is required to determine whether and how international trade causes environmental problems or whether it can be a solution for tackling growing environmental challenges.

Trade Governance and Environmental Governance

Recently, the use of trade rules as instruments for promoting environmental protection has generated considerable interest. One reason is that environmental agreements have several weaknesses that cast doubt on their capacity to tackle global environmental challenges, even though the number of environmental agreements is increasing. Global environmental governance seeks to make progress based on consensus, which tends to lead to agreements that lack ambition and capacity to overcome pertinent environmental problems (Reference Susskind and AliSusskind & Ali, 2014). Moreover, most global environmental agreements lack strong enforcement mechanisms, which can undermine compliance and lead to free riding. Given the weaknesses of global environmental governance, other avenues for environmental protection are being pursued.

Conventionally, trade and the environment used to be governed by distinct regimes. At the same time, attempts to link trade and environmental governance have been underway for decades. This has led to increasing overlap and interactions between different regimes (e.g., Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2015; Reference Zelli, Gupta and Van AsseltZelli et al., 2013). In recent years, there has been a remarkable shift in the development of novel ways to link trade with the environment. Trade agreements concluded at the bilateral or regional level are central to this development.

Environmental provisions have become a regular feature of PTAs. PTAs offer several advantages over multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) in terms of negotiating environmental obligations: they reduce the number of players around the negotiation table, facilitate trade-offs across diverse issue areas, are associated with established practices to ensure compliance and enforcement (see also Box 1), and the political involvement of heads of government can help break deadlocks and accelerate the negotiation process. As a result, some PTA environmental provisions set obligations that are more specific, more stringent, and characterized by better enforceability than those contained in environmental agreements.

The Increasing Number of Environmental Provisions

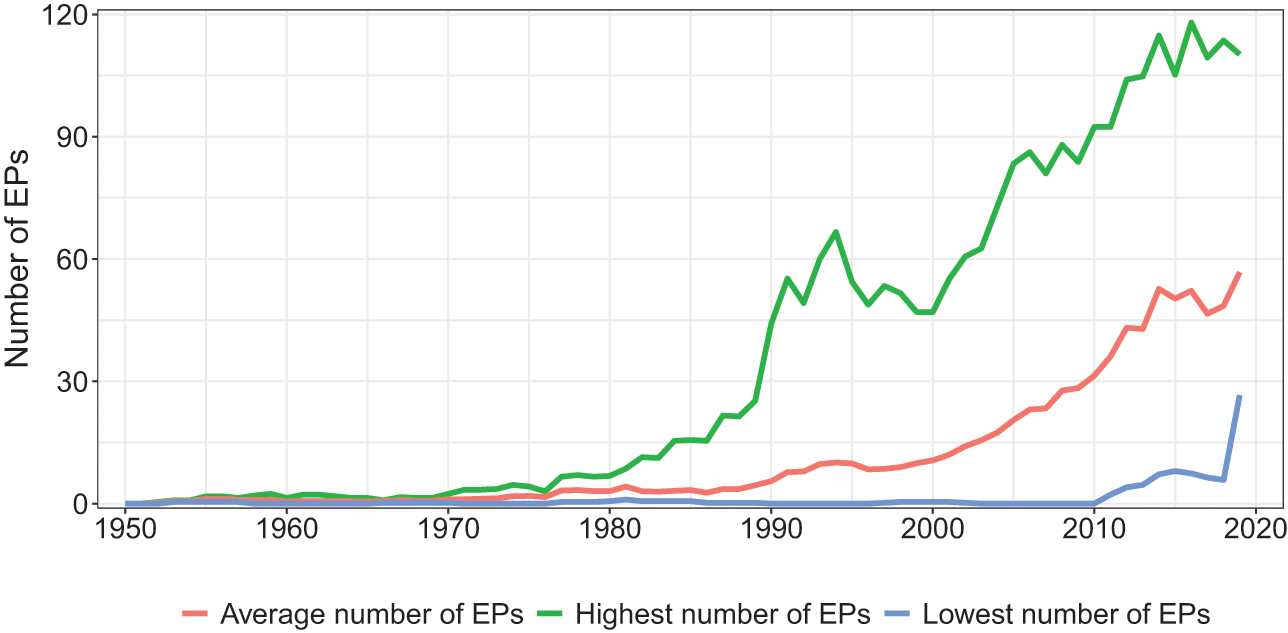

More than 86 per cent of all PTAs include environmental provisions (Reference Morin, Dür and LechnerMorin et al., 2018b). As shown in Figure 3, almost all new PTAs systematically incorporate environmental provisions (with the recent exception of the 2020 sectoral agreement between Brazil and Paraguay).

Figure 3 Bar chart, per cent of PTA with environmental provisions over time

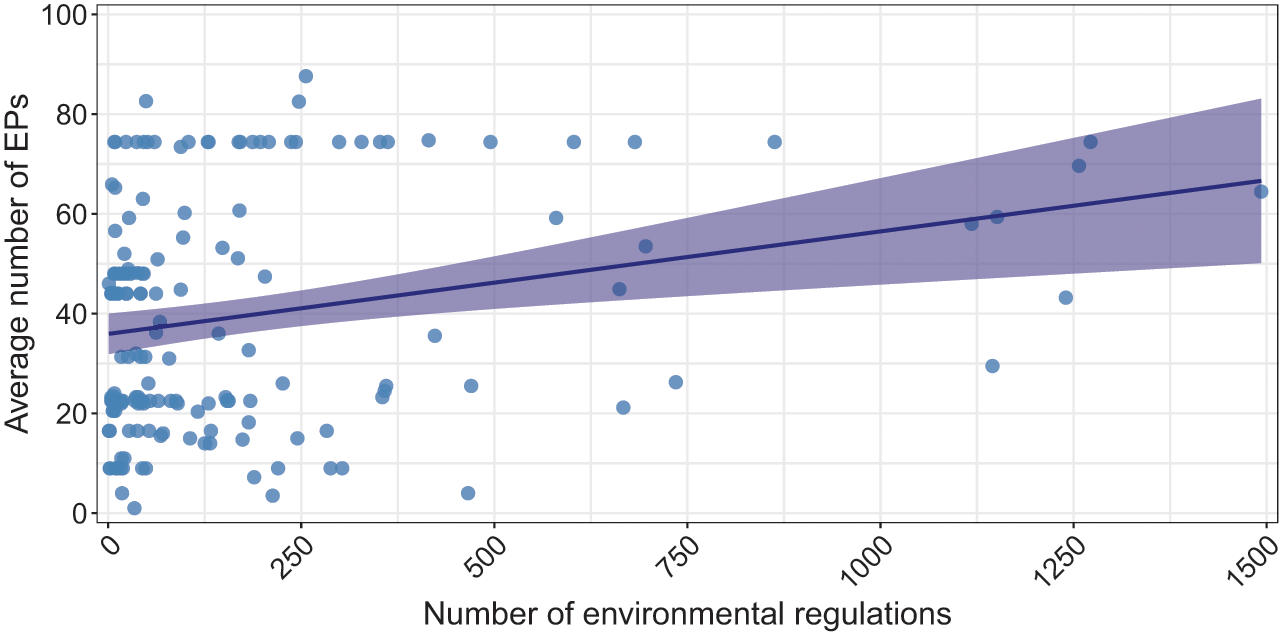

As depicted in Figure 4, the average number of environmental provisions in PTAs has increased over time.Footnote 10 Between 2015 and 2020, each new PTA had an average of forty-eight environmental provisions, illustrating the proliferation of environmental provisions in the trade regime complex. Recent PTAs often include more than 100 environmental provisions. In 2019, the signing of the Agreement between the US, Mexico, and Canada (USMCA), often referred to as NAFTA 2.0, broke a new record: this PTA has 153 environmental provisions.

Figure 4 Number of EPs per PTA over time

Substantial variation subsists in the average number of environmental provisions per PTA (see also Reference BakerBaker, 2021). American trade agreements include an average of forty-nine environmental provisions. European PTAs include an average of twenty-six environmental provisions. The difference between US and EU average is chiefly due to the fact that several European PTAs have been concluded in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, before the number of environmental provisions per PTAs took off around the world. In Asia, environmental provisions have only recently become more prominent in trade agreements. China is a regional leader, with an average of twenty-three environmental provisions per PTA. Yet, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which entered into force in 2022 between China, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and Republic of Korea and the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and accounts for approximately 30 per cent of global GDP, is almost silent on the environment. PTAs involving African countries have an average of twelve environmental provisions. The recently launched African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), comprising fifty-four African states, includes few environment provisions, indicating substantial untapped potential that is yet to be leveraged in future negotiations for PTAs involving African partners.

The Increasing Diversity of Environmental Provisions

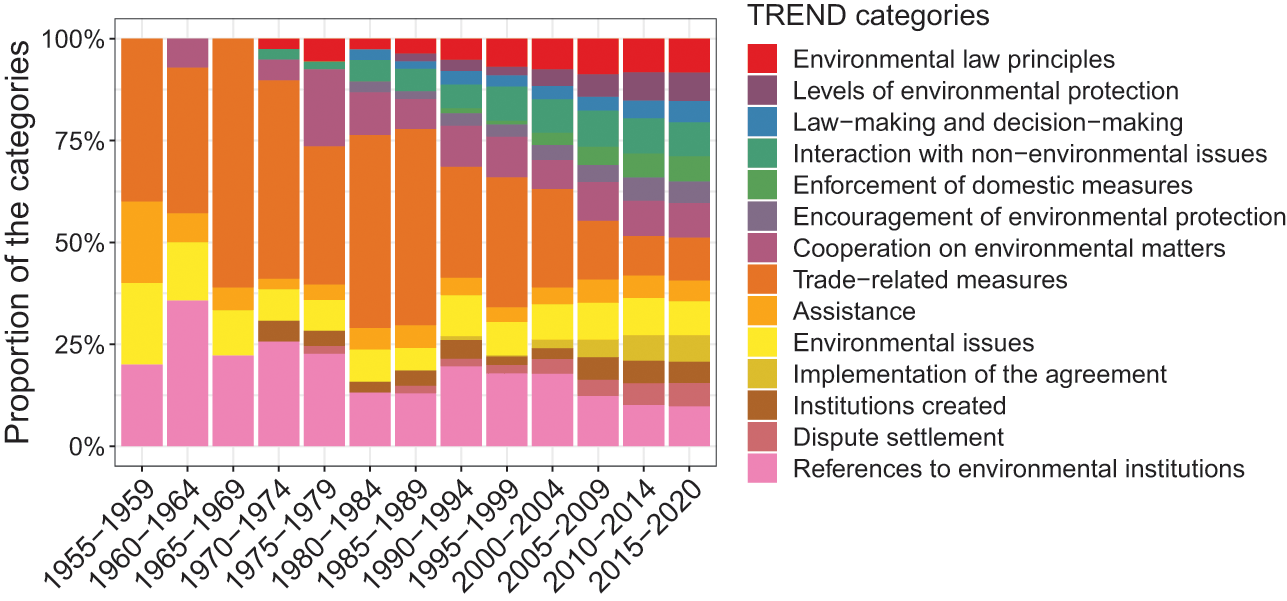

Environmental provisions in PTAs are not only multiplying; they are also becoming increasingly diverse and far-reaching (see Figure 5).Footnote 11 Environmental provisions include environmental law principles, such as common but differentiated responsibilities or the polluter pays principle; provisions that regulate or refer to the level of domestic environmental protection; provisions that govern environmental law-making and policy-making, for example, demanding the participation of NGOs or citizens in the adoption of environmental measures; provisions that govern the interaction with non-environmental issues; provisions that refer to the enforcement of domestic environmental measures; provisions that encourage environmental protection; provisions that govern cooperation on environmental matters; provisions that refer to trade-related measures; provisions that focus on assistance; provisions that refer to specific environmental issues; provisions that concern the implementation of the agreements; provisions that demand the creation of new institutions; provisions that refer to the settlement of disputes; and, lastly, provisions that refer to environmental institutions, such as the Paris Agreement.

Figure 5 Types of environmental provisions

Some of these provisions entail so-called environmental exceptions that permit countries to limit trade to conserve natural resources, similar to those in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) of 1947, which is now part of the WTO (GATT Article XX(b)). These exceptions are included in Figure 5 under the category ‘Trade-related measures’, which until recently was the most frequent type of environmental provision.

At the same time, PTAs have numerous environmental provisions with greater scope than the relevant provisions in the WTO. For example, some PTAs include environmental provisions that promote the harmonization, the reinforcement, and the implementation of environmental policies; back-up MEAs; demand the transfer of environmental technologies to developing countries, as well as environmental capacity-building; facilitate civil society activity; and cover manifold environmental issues, such as limiting deforestation, protecting fish stocks, reducing hazardous wastes, and mitigating CO2 emissions. In recent years, PTAs have included an increasing number of environmental provisions that are not trade related. PTAs have become vectors for negotiating environmental obligations, which were previously debated in fora exclusively devoted to the environment.

As Figure 6 shows, the most prevalent environmental issue areas in PTAs are waste, biodiversity, water, fisheries, and forests. Environmental provisions that focus on these issues are particularly frequent in North-South and South-South PTAs. In recent years, trade agreements have increasingly addressed climate change (on the diffusion of climate-related provisions, see Section 6).

Figure 6 Number of PTAs with at least one environmental provision addressing the issue area

Recently, PTAs have been directly linked to many SDGs. For example, they contain provisions to encourage trade in energy-efficient goods (SDG 7), ratify the Paris Agreement (SDG 13), prevent maritime pollution (SDG 14), and protect and sustainably manage forests (SDG 15). Thus, one might expect that PTAs with environmental provisions can support the implementation of a number of SDGs and promote the environmental dimension of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. So far, the actual effects of environmental provisions in PTAs on different aspects of sustainable development have remained unclear. We will shed light on the environmental and economic consequences of environmental provisions in Section 7.

The Key Role of the US

The US, which has prioritized trade and environment linkages since NAFTA, raised the prominence of both labour and environmental issues in trade policymaking. Strengthening environmental standards in foreign markets to ease competitive pressure has become one of the main objectives of American trade policy. In 1992, this goal became manifest when NAFTA was adopted with a side agreement, the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation. One of the main aims of this side agreement was to ensure that parties would enforce their own environmental regulations. Environmental NGOs, labour unions and businesses in the US were worried that Mexico would fail to adequately enforce its domestic regulations to cut back costs and become more attractive for foreign investments (Interview with US official, 2017).

The US approach is characterized by its attention to enforcement (Reference VelutVelut et al., 2022). Several US agreements provide that civil society actors can file complaints for a country’s failure to enforce its own environmental obligations. In some US deals, trade sanctions can be used as an enforcement tool: when there is persistent failure to enforce domestic environmental measures, an arbitral panel can levy a monetary fine, and in case of non-payment, a party has the right to trade retaliation (Reference Morin and RochetteMorin & Rochette, 2017).Footnote 12 As a result of these mechanisms, US partners are incentivized to implement their obligations prior to the entry into force of the agreement (Reference Bastiaens and PostnikovBastiaens & Postnikov, 2017). This improved the implementation of measures related to the protection of endangered species in Peru, following the 2009 US-Peru PTA (Reference Jinnah and MorinJinnah & Morin, 2020).

The Key Role of the EU

Since the 1990s, the EU has regarded itself as a normative power, actively promoting norms beyond its borders. In the context of EU trade policy, this goal has been particularly prominent since the turn of the last century (Reference Poletti and SicurelliPoletti & Sicurelli, 2018). When multilateral negotiations became increasingly stuck, the EU focused on promoting PTA. The aim was to conclude comprehensive trade agreements that foster trade and investment and strengthen regulatory standards, rule of law, and sustainable development (European Commission, 2015).

The EU has included comprehensive Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) chapters in its trade agreements since the 2009 PTA with South Korea. The approach in the European TSD chapters is based on three pillars: multiple environment-related commitments, many of which are linked to a range of MEAs; the participation of civil society organizations to help implement the commitments; and a dedicated dispute settlement mechanism whereby independent arbitrators make findings on compliance public (European Commission, 2018). When the UN Agenda 2030 on SDGs and the Paris Agreement were adopted in 2015, the European Commission began revising its TSD chapters. For instance, the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement, signed in 2016, includes three chapters that deal with sustainable development, labour, and the environment (Reference VignarelliVignarelli, 2021). While the EU focuses on using trade policy and related instruments for sustainability, a review of six recent EU PTAs shows that substantial potential remains untapped, namely: the use of environmental provisions to mitigate the negative impacts of trade and the use of trade to boost environmental sustainability (Reference KettunenKettunen et al., 2021).

Other Players

Historically, the US and EU have played a pioneering role in extending environmental provisions, showcasing how PTAs can enable experimentation and promote innovation in the trade regime complex. However, extensive environmental provisions are now included in agreements that do not involve either party. One recent PTAs with innovative provisions in their areas of climate change was concluded in 2021 between Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and the UK. It recalls the objective of limiting temperature increase to 1.5 degree above pre-industrial level, it reaffirms the parties’ nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement, it encourages trade in goods and services that ‘are of particular relevance for climate change mitigation and adaptation’, it commits parties to cooperate on offshore wind generation, hydrogen technologies, and carbon capture, it supports reductions targets for international aviation and maritime transportation, and it calls for a global phase-out of fossil fuel subsides (Article 13.22).

Although environmental provisions are less frequent in PTAs between developing countries, developing and emerging economies increasingly include them in their most recent PTAs (Reference Berger, Brandi, Bruhn and MorinBerger et al., 2017). Developing countries used to prioritize support for more traditional trade issues such as export competitiveness, industrialization, quality infrastructure, and trade facilitation. However, more recently, there has been a substantial increase in interest for cooperation on environmental issues, for example, by the countries of the Andean Community in their negotiations with the EU (interview with EU Commission, 15 November 2021). A growing number of developing countries are incorporating environmental provisions in South-South trade agreements (Reference Lechner and SpilkerLechner & Spilker, 2021). The trend towards linking trade and the environment in PTAs might be related to the fact that citizens in developing countries tend to support the insertion of environmental provisions in PTAs (Reference Bernauer and NguyenBernauer & Nguyen, 2015).

At the same time, some political leaders in developing countries are concerned that environmental provisions are used as a means to disguise ‘green protectionism’. They argue that high-income countries try to use environmental regulations to create barriers to trade, which could limit their ability to export goods to their markets. Indeed, some negotiators are still sceptical about ambitious environmental provisions, which are promoted by high-income countries (interview with EU Commission, 24 November 2021). Developing countries are also concerned about unilateral policy approaches, such as the European CBAM.

However, leaders from developing countries are increasingly positive about linking trade and the environment in the context of preferential trade negotiations (Interview with EU Commission, 15 November 2021). Many developing countries, such as Costa Rica, are now proactively moving trade and environmental interlinkages forward in the multilateral context and in the Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions (TESSD) recently launched at the WTO (see also Section 8). Simultaneously, developing countries favour environmental provisions related to issues that they care about deeply, such as waste, water, and biodiversity. In South-South PTAs, these issue areas are especially important (see Figure 6). For instance, Peru and Colombia have been leaders in introducing biodiversity provisions in the trade system (Reference Morin and GauquelinMorin & Gauquelin, 2016).

Governments in many developing and emerging economies seem to be moving towards a more open approach that links trade and the environment. In major emerging economies, the situation varies. As mentioned above, while China includes a substantial number of environmental provisions in its average PTA, the country has been criticized for its lack of focus on the environment in the recently concluded RCEP. In 2020, China and the EU signed a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, which commit China to effectively implement the Paris Agreement and to make continued efforts to address climate change. India’s PTAs typically include several provisions related to environmental protection, although their implementation has been criticized as insufficient. Overall, there is still significant room for improvement in major emerging economies but some progress has been made.

Compliance and Enforcement Mechanisms

Intergovernmental committees provide a framework for regular exchanges on compliance with environmental provisions. The 2011 PTA between the EU and Korea, for instance, created a Committee on Trade and Sustainable Development comprising officials from both parties. They come together regularly to discuss the implementation of environmental provisions and help define priorities for cooperation (Reference Morin, Chaudhuri and GauquelinMorin et al., 2018a).

In addition to intergovernmental mechanisms, civil society participation can help promote PTA implementation. In the EU, domestic advisory groups (DAGs), representing various branches of civil society, are set up in the EU and in each partner country to help monitor and provide advice on implementation. The establishment of civil society forums creates a space for wider civil society participation in monitoring the implementation of PTAs. Although many countries have expressed their support for the involvement of civil society in trade policymaking, a number of PTAs focus on ad hoc consultations for the implementation of PTAs instead of institutionalized civil society committees, such as EU domestic advisory groups, which meet roughly once a year (Reference VelutVelut et al., 2022, p. 112).

Do joint institutions created by PTAs such as intergovernmental committees or civil society forums effectively promote compliance? Insights drawn from interviews indicate that their effectiveness can be limited for several reasons (Reference Morin, Chaudhuri and GauquelinMorin et al., 2018a). Actors that are supposed to work together in the framework of these joint institutions, such as civil society actors, are not always sufficiently organized or may lack the necessary government support to make use of these options. In some joint institutions, the institutional design lacks a clear focus on environmental protection, which means that more traditional trade issues tend to overshadow environmental concerns. In other cases, the relevant institutions are never established because there is not much interest or the present institutions are considered more appropriate.

Technical assistance and capacity building also play important roles in the implementation of multiple PTAs. By now, 14 per cent of the 775 examined PTAs include provisions on technical assistance and capacity-building. In addition, 10 per cent also include financial or technology transfer commitments. For example, the US regularly offers assistance through several different measures, including training in resource management and environmental enforcement, public awareness campaigns, the transfer of environmentally friendly technologies, assistance for the creation of protected areas, and legal advice on new environmental laws (Reference Morin, Chaudhuri and GauquelinMorin et al., 2018a). Measures, such as the establishment of wastewater laboratories in Central America or the development of an electronic system for tracking timber in Peru, have been implemented. The 2006 US-Peru PTA defines US commitments for providing technologies and training for forest conservation and the protection of endangered species in Peru. As a result of the PTA, for instance, an electronic system for tracking timber has been put in place in Peru.

In some PTAs, the non-compliance with environmental provisions is subject to the PTA’s dispute settlement mechanisms (DSM), which can eventually lead to trade sanctions. EU PTAs rely solely on a cooperative policy dialogue approach to enforce environmental provisions. In the event of disagreement, parties can initiate government consultations. If the dispute is not resolved during this phase, a panel of experts convenes and writes a report with recommendations to help the parties resolve the dispute. The TSD committee monitors the implementation of the panel’s recommendations.Footnote 13

Research suggests that both sanction-based and cooperative approaches can be effective (Reference Bastiaens and PostnikovBastiaens & Postnikov, 2017). However, the enforcement of environmental provisions remains controversial. In particular, the EU’s approach to its TSD chapters is frequently criticized for being weaker (Reference VignarelliVignarelli, 2021). Some studies find that TSD chapters (EU Commission, 2017) and environmental provisions in EU PTAs (Reference Bastiaens and PostnikovBastiaens & Postnikov, 2017) have been effective. However, other studies are more critical (Reference Harrison, Barbu, Campling, Richardson and SmithHarrison et al., 2019). Many stakeholder groups believe that policy instruments other than trade agreements are more effective for pursuing non-trade policy goals, such as environmental protection (Reference Yildirim, Basedow, Fiorini and HoekmanYildirim et al., 2021).

In the light of this debate, the EU has recently started working on a new TSD approach to its trade agreements. In 2018, EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström unveiled a 15-Point Action Plan to increase the effectiveness of EU TSD chapters in PTAs. The plan sets out to ensure that countries comply with their commitments. It includes more assertive enforcement mechanisms, facilitates civil society’s monitoring role, and makes EU resources available to support the implementation of TSD chapters. In 2021, the European Commission published its Trade Policy Review, entitled ‘An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy’, which focuses on trade and sustainable development in EU PTAs. In 2021, the European Commission also initiated a review of the 15-Point Action Plan on TSD to reflect on additional steps to improve the implementation and enforcement of TSD chapters. Measures include ‘the possibility of sanctions for noncompliance’ (EU Commission, 2018).

Some scholars, experts, and civil society representatives argued that the EU should move towards the US sanction-based enforcement approach (Reference Bronckers and GruniBronckers & Gruni, 2021).Footnote 14 Others are sceptical about the effectiveness of sanctions (Reference DuránDurán, 2020; Reference Hradilova and SvobodaHradilova & Svoboda, 2018). For example, the recent case of the dispute between the US and Guatemala under the labour provisions of the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement suggests that the sanction-based approach may not be the best way to tackle non-compliance with labour and environmental standards insofar as the outcome of this dispute was a disappointment for many who had hoped for a positive precedent for workers. More generally, threats and sanctions can lead to political backlashes and counterproductive reactions. Instead, cooperation between parties and capacity-building are often regarded as more promising for promoting compliance. This is largely because some of the major obstacles to the enforcement of environmental provisions in PTAs are linked to improving civil society participation, cooperation between PTA parties, and monitoring of compliance with the PTA (Reference Hradilova and SvobodaHradilova & Svoboda, 2018).

In 2022, the European Commission put forward the new communication ‘The Power of Trade Partnerships: Together for Green and Just Economic Growth’ on how to further strengthen the implementation and enforcement of TSD chapters in EU PTAs. For instance, in the document, the Commission proposes to strengthen provisions in new PTAs and accepts the use of trade sanctions as the recourse of last resort against instances of serious violations of these commitments. In practical terms, communication should also make it easier for Domestic Advisory Groups (DAGs) that are set up to monitor agreements to raise complaints. Although this approach still has to prove itself in practice, it seems to be a promising compromise. While a rigid sanction-based mechanism may be needed in certain contexts (Reference Jinnah and LindsayJinnah & Lindsay, 2016), it should not substitute for a softer cooperative approach (Reference Morin, Chaudhuri and GauquelinMorin et al., 2018a). Both approaches are complementary. When they exist side by side in the same trade agreement, they can induce major improvements in compliance.

The debate about the effective implementation and enforcement of environmental provisions in PTAs also concerns European trade deals under negotiation. In 2019, after two decades of negotiations, the EU and Mercosur reached a political agreement on a new trade deal that would have significant geopolitical importance for the EU. However, several EU member states, the European Parliament, and civil society organizations have strong reservations about ratifying the deal. Although the PTA includes multiple environmental provisions, environmentally concerned stakeholders are worried about its negative environmental impact and the effectiveness of its environmental provisions, especially through deforestation. In their view, the European approach to enforcement is too weak. The EU-Mercosur agreement mobilized various political interest groups, especially environmental NGOs, but also the European agricultural lobby. The deal was not ratified in 2020 as planned and was instead put on hold. The election of Brazilian President Lula in 2022 presents a fresh opportunity to revise and ultimately conclude the agreement as he is more receptive to environmental considerations than his predecessor. Overall, while the EU largely focuses on using trade policy and related instruments to achieve sustainability goals, key improvements in EU PTAs’ sustainability-related provisions are required. More assertive implementation could help deliver the vision put forward by the European Green Deal, a package of policy initiatives (including climate, energy, transport, and taxation policies) to attain the EU’s goal of reaching climate neutrality by 2050.

Beyond the US and EU, there is no universal approach to the enforcement of environmental content in PTAs. Enforcement varies depending on the specific agreement and countries involved. Generally, the enforcement of environmental provisions in PTAs involves a mix of mechanisms, including monitoring, dispute settlement, and cooperation. Some PTAs include all aspects, whereas others are limited to a single element. Additionally, the level of enforceability of environmental provisions differs across PTAs. They may refer to a relatively weak ‘strive to ensure’ approach (e.g., in earlier US agreements), a more stringent ‘shall not fail to effectively enforce’ approach (e.g., in recent US and New Zealand’s PTAs) or an even more stringent ‘shall promote compliance with and effectively enforce’ environmental laws (e.g., in Canadian PTAs) (Reference VelutVelut et al., 2022).

Civil Society Participation

Civil society participation can improve stakeholders’ input throughout the trade policy process (Reference VelutVelut et al., 2022, p. 20–1): First, prior to negotiations and during the negotiation phase, environmental impact assessments and civil society consultations help countries identify the problems likely to arise for compliance with the PTA. For instance, when the US-Peru FTA’s Forest Annex was drafted, environmental NGOs offered substantial input. Second, during the implementation phase, technical assistance and capacity-building approaches combined with civil society participation can generate better outcomes than those that focus solely on state actors. This type of civil society engagement requires adequate funding, as in the case of the Canada-Colombia PTA in force since 2011. Third, in the context of enforcement, public submissions for non-compliance are key. For example, in 2011, a local Mexican community organization filed a submission under NAFTA’s environmental side agreement, stating that the Mexican government was not adequately enforcing its environmental laws in the context of limestone extraction in the Sumidero Canyon National Park (Reference VelutVelut et al., 2022, p. 23). This action had a positive impact on the environment. The case of Sumidero Canyon illustrates how effective it can be to enable civil society to participate in PTA enforcement mechanisms.

Overall, environmental provisions are increasingly varied and far reaching and some can play a major role in environmental governance. However, the factors that drive the inclusion of environmental provisions in PTAs and the implications of PTA involvement in environmental governance remain unclear. Against this background, we assessed 298 different types of environmental provisions in 775 PTAs to explore why they spread (Section 4), the North-South dynamics they involve (Section 5), how they are diffused (Section 6), what effects they have (Section 7), and their potential for multilateral agreements (Section 8).

Box 1 Sustainable palm oil in the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA): A new mechanism to strengthen environmental protection through trade

In 2018, Indonesia signed the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with the European Free Trade Association, which includes Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. The CEPA went into effect in 2021 and includes an innovative regulatory mechanism designed to encourage environmental protection through international trade. Specifically, for palm oil imports, the tariff reductions under CEPA only apply to Indonesian palm oil that meets specific sustainability criteria, such as ending deforestation, peat drainage, and fire clearing (Reference Sieber-GasserSieber-Gasser, 2021). Swiss importers of Indonesian palm oil must ensure that their imports are certified under the voluntary sustainability standard of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to benefit from CEPA tariff preferences.

Although Switzerland only imports small amounts of Indonesian palm oil, the environmental provision under CEPA could serve as a precedent for future PTAs. This is especially relevant to the ongoing negotiations between the EU and Indonesia for a PTA, where palm oil trade remains a contentious issue (Reference BrockBrock, 2022). Indonesia has proposed certifying ‘sustainability’ under the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) scheme, but the EU is unlikely to accept it due to its perceived shortcomings. Nevertheless, the new regulatory mechanism under CEPA has the potential to promote sustainability through trade beyond the palm oil sector.

4 Drivers of Environmental Provisions in PTAs

Research on the incorporation of environmental provisions in PTAs has provided several possible explanations for what drives this trend. However, such research is typically based on case studies of individual agreements, such as NAFTA and its side agreement on environmental cooperation. Although NAFTA offers significant insights, the drivers that apply to this specific agreement may not necessarily apply to the broader set of existing PTAs. As we approach the three-decade mark since the implementation of NAFTA, and with hundreds of PTAs now featuring increasingly diverse and extensive environmental content, it is imperative that we expand our focus beyond single-case analysis.

To date, systematic research on the various drivers of environmental provisions across the entire universe of trade agreements remains limited primarily because of the lack of comprehensive data on the environmental content of PTAs. This section discusses existing scholarship on various drivers of environmental provisions and analyses why particular types of countries may prefer specific types of environmental provisions. Through this approach, we hope to deepen our understanding of the drivers of environmental provisions in PTAs.

Response to Electoral Pressures or a Sceptical Public

The inclusion of environmental provisions in PTAs might be driven by the hope of making these PTAs more palatable to a sceptical public (Reference PostnikovBastiaens & Postnikov, 2020), including pro-environmental political parties and non-state actors opposed to trade liberalization, who would otherwise prevent the conclusion of trade agreements (Reference GallagherGallagher, 2004; Reference Hufbauer, Esty, Orejas, Schott and RubioHufbauer et al., 2000). For instance, American environmental NGOs put pressure on the US government in 1992 to incorporate environmental provisions in NAFTA (Reference GallagherGallagher, 2004).

The view that environmental provisions are a response to these types of pressure is supported by the fact that democracies incorporate more environmental provisions in their trade agreements than autocracies (Reference Morin, Dür and LechnerMorin et al., 2018b). Democracies (Polity2 score greater than 16) contain on average six times more environmental provisions than autocracies. Figure 7 shows the correlation between the Polity2 score (Reference Marshall, Gurr and JaggersMarshall et al., 2020) of a country and the average number of provisions in PTAs concluded between 2000 and 2020. At the same time, some PTAs with democratic members have few environmental provisions.

Figure 7 Regime type and environmental provision

Environmental Objectives

A second driver is that policymakers make use of PTAs to improve environmental regulations, and that PTAs’ environmental provisions are used to push environmental objectives beyond typical environmental institutions (Reference Jinnah and LindsayJinnah & Lindsay, 2016; Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2015). Negotiations in multilateral environmental fora advance slowly. By contrast, trade negotiations between a smaller set of countries can facilitate the inclusion of extensive environmental obligations by enabling trade-offs across different issue areas and by side-stepping countries that block progress. This is in line with a survey in which negotiators stated that they use PTAs’ environmental provisions to promote environmental protection (Reference GeorgeGeorge, 2014).

Both the US and the EU use environmental provisions to spread their domestic norms across the world (Reference Jinnah and LindsayJinnah and Lindsay, 2016; Reference Poletti and SicurelliPoletti and Sicurelli, 2016). For instance, the US can extract more commitments on forestry and endangered species when these issues are negotiated in the context of a trade agreement (Reference JinnahJinnah, 2011). In fact, some provisions on endangered species in the 2009 US-Peru PTA are more detailed and characterized by better enforceability than those included in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). These environmental provisions ‘have the potential to enhance environmental regime effectiveness in ways that have been impossible under environmental treaties alone’ (Reference JinnahJinnah, 2011, p. 191).

In the EU, trade agreements are frequently used to promote non-trade goals, including environmental protection. The aim is to use trade as leverage to promote environmental standards (interview with EU Commission, 24 November 2021). In particular, the EU has gradually integrated its climate agenda into its trade negotiations. As early as 1979, the Lomé II Convention, concluded between Europe and African, Caribbean and Pacific countries, promoted renewable energy and energy efficiency. In 1989, before the first report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was published, the Lomé Convention was revised to include a reference to the greenhouse effect. In the 1990s, certain EU trade agreements reaffirmed the importance of international cooperation on climate change and incorporated increasingly detailed provisions. Today, climate change provisions are part of all recent EU trade agreements. Climate change has gradually become a key element in EU trade negotiations, directly contributing to EU environmental objectives.

Interest in the use of trade agreements to promote environmental objectives is in line with the observation that greener countries tend to include more environmental provisions in their trade agreements. As shown in Figure 8, a higher Environmental Protection Index (EPI) correlates with a greater number of environmental provisions.Footnote 15 An increase of the EPI by ten points is associated with four additional environmental provisions in PTAs. Environmental leaders incorporate more environmental provisions in their PTAs than laggards.

Figure 8 Environmental protection and environmental provisions

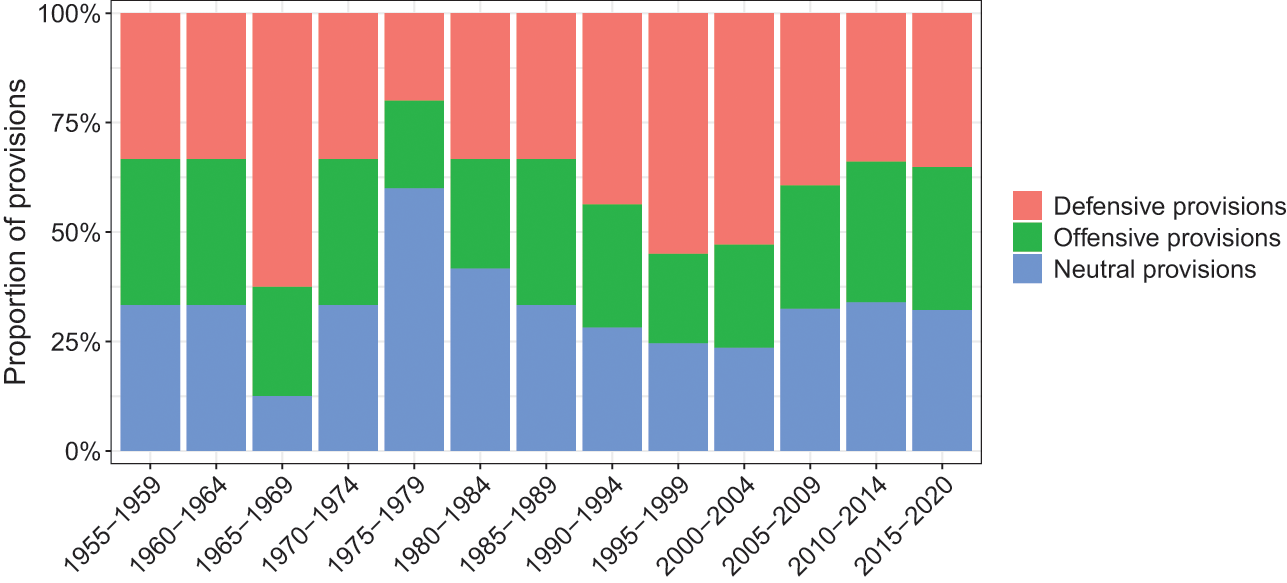

Safeguard against Trade Disputes

Another explanation is that negotiators include environmental provisions in PTAs in response to trade disputes (Reference PauwelynPauwelyn, 2014), which frequently concern domestic environmental regulations. Some of the most well-known GATT/WTO disputes are related to environmental standards, including the tuna-dolphin and the shrimp-turtle (see Box 2). In fact, a number of environmental provisions help preserve countries’ regulatory sovereignty in favour of environmental protection, while shielding countries against legal disputes of this type. We refer to these as defensive environmental provisions. They safeguard a country’s policy space for environmental regulations and prevent countries from being involved in legal disputes (Reference Blümer, Morin, Brandi and BergerBlümer et al., 2020). A widespread example of a defensive environmental provision is the exception to trade commitments for domestic measures deemed necessary to protect the life of plants and animals (GATT Article XX(b)).

Box 2 Environmental disputes in the GATT/WTO

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the WTO, have been the centre of many environmental disputes since their creation. While their primary objective is to facilitate international trade and reduce trade barriers, environmental concerns often conflict with these goals.

One of the most significant environmental disputes in the GATT/WTO concerns the US ban on tuna imports. In 1991, the US enacted a law that required all tuna caught using a fishing method that harmed dolphins to be labelled as ‘dolphin-safe’ and banned from importation. Mexico, which relied heavily on this fishing method, challenged the law at the GATT.