Summations

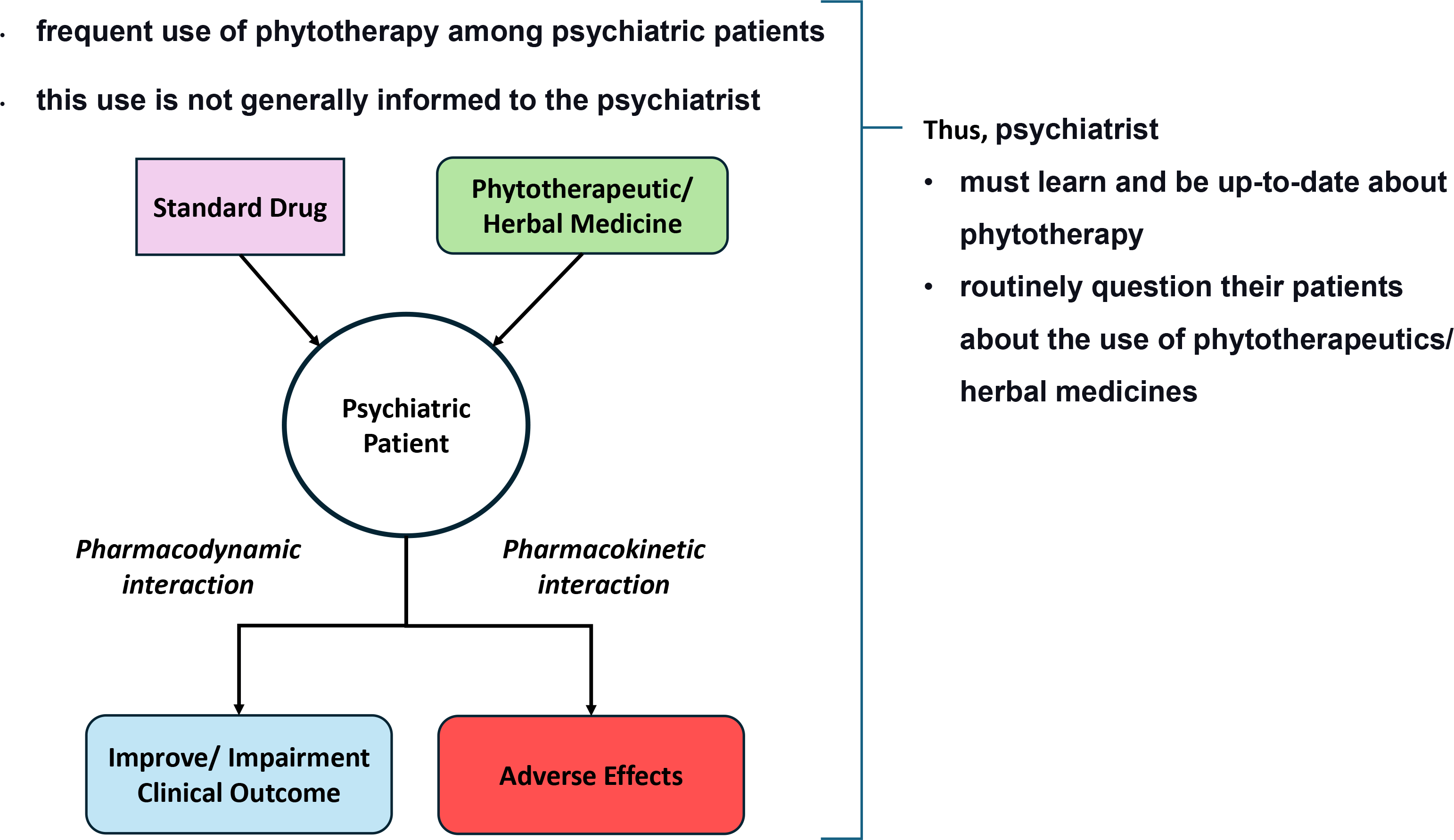

There is a significant use of CAM among psychiatric patients and this use is not generally informed to the psychiatrist

Phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines have a risk of adverse effects and drug-herb interactions

The psychiatrist must learn and be up-to-date about phytotherapy and routinely question their patients about the use of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines

Perspectives

Stimulate studies evaluating the use of phytotherapy/herbal medicines by psychiatric patients using similar methodologies (e.g., standardised questionaries or interviews both for psychiatric diagnosis and CAM, as I-CAM to detect CAM/phytotherapy use) and done in different settings (e.g., outpatients, inpatients).

The inclusion of phytotherapy theme in the medical curriculum, books, articles, and events about drug treatment of psychiatric disorders, discussing its efficacy (and inefficacy), mechanisms of action, adverse effects, and drug interactions.

Teaching principles and clinical aspects of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicine to undergraduate medical students and trainees/interns in psychiatry.

Introduction

A definition of Alternative (or unorthodox, complementary) Medicine is difficult, as this term encompasses a wide range of practices and beliefs. Frequently Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) are defined as treatments that were not taught in Western medical schools and/ or not widely used/ available in clinics/hospitals (de Jonge et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Hoenders, Evans-Lacko, Kovess-Masfety, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Bunting, Caldas-de-Almeida, Dinolova, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Huang, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lépine, Levinson, Makanjuola, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Scott, Tachimori, Williams, Wojtyniak, Kessler and Thornicroft2018). Alternatively, they have been defined as practices that are not integrated into the mainstream healthcare system, and/ or that were not incorporated into the national health system (World Health Organization, 2019). CAM includes methods such as, for example, acupuncture, homeopathy, and phytotherapy/herbal medicine (Wetzel et al., Reference Wetzel, Eisenberg and Kaptchuk1998; de Jong et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Hoenders, Evans-Lacko, Kovess-Masfety, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Bunting, Caldas-de-Almeida, Dinolova, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Huang, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lépine, Levinson, Makanjuola, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Scott, Tachimori, Williams, Wojtyniak, Kessler and Thornicroft2017). However, it is noteworthy that some of these methods (e.g., phytotherapy) are increasingly addressed in medical education and are being offered in many outpatient clinics, university centres, traditional medical institutions, and public health systems. For example, Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Marques, Soares, Slomp Junior, Sanches and Mello2023) discuss the importance of including this topic in the current medical curriculum in general and for Family and Community Medicine residents in particular. Thus, the boundaries between CAM and conventional medicine are getting blurred.

CAM use in the general population and psychiatric patients

An important consideration regarding these practices, even for medical professionals who do not adopt them, is that a significant part of the general population (ranging from 5 to 50%) uses various forms of CAM (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Kessler, Foster, Norlock, Calkins and Delbanco1993; MacLennan et al., Reference MacLennan, Wilson and Taylor1996; Unützer et al., Reference Unützer, Klap, Sturm, Young, Marmon, Shatkin and Wells2000; Tindle et al., Reference Tindle, Davis, Phillips and Eisenberg2005; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas2012; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Nortje, Makanjuola, Oladeji, Seedat and Jenkins2015; Rashrash et al., Reference Rashrash, Schommer and Brown2017; Rashrash et al., Reference Rashrash, Schommer and Brown2017; Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues, Reference Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues2022). Using the variable ‘visit to CAM providers’ instead of ‘CAM use’, the prevalence across studies ranges from 2 to 49% (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas2012). More recently, Peltzer and Pengpid (Reference Peltzer and Pengpid2018) found a 12-month prevalence mean of 26% from a sample of 32 countries, ranging from 6% (Polland and Slovenia) to 53% (China and Philippines). This wide variance in the prevalence of CAM use observed in these studies could be related to differences in cultural characteristics, in the sample studied, and methodological design, among others.

Around 18% of the patients try CAM before conventional medicine and 20% of CAM users justify their use to add it to conventional medicine (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Jones, Browne and Leslie2014). Thus, it is common for patients to use CAM concomitantly with prescription medications, not as a replacement for them (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Jones, Evans and Leslie2012), justifying the concept of Complementary Medicine.

Astin (Reference Astin1998) listed as patients’ motivations for searching for CAM: (a) people with a higher educational level; (b) worse health status; (c) a ‘holistic’ view of health; (d) lived an experience that led to a change in worldview; (e) certain cultural attitudes (feminism, personal psychological growth, and spirituality); and (f) certain disorders such as anxiety, ‘back problems’, and chronic pain. These are in line with studies that evaluated the factors associated with CAM use (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Kessler, Foster, Norlock, Calkins and Delbanco1993; Tindle et al., Reference Tindle, Davis, Phillips and Eisenberg2005; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas2012; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas2012). A similar association was found between visits to CAM providers and gender (female) (Peltzer and Pengpid, Reference Peltzer and Pengpid2018).

However, the country’s development and cultural factors can affect the influence of these factors. For example, in low-income countries, phytotherapeutics are used by patients with higher educational levels and income while in higher-income countries, higher use of CAM is observed in low-income and low-educational level populations (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Kessler, Foster, Norlock, Calkins and Delbanco1993; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Cooper, Relton and Thomas2012; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Jones, Evans and Leslie2012; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Nortje, Makanjuola, Oladeji, Seedat and Jenkins2015; de Jong et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Hoenders, Evans-Lacko, Kovess-Masfety, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Bunting, Caldas-de-Almeida, Dinolova, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Huang, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lépine, Levinson, Makanjuola, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Scott, Tachimori, Williams, Wojtyniak, Kessler and Thornicroft2017; Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues, Reference Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues2022).

Regarding the use of CAM by patients with psychiatric disorders or from psychiatric services, the studies indicate an association with anxiety and mood disorders (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Kessler, Foster, Norlock, Calkins and Delbanco1993; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Nortje, Makanjuola, Oladeji, Seedat and Jenkins2015; Hansen and Kristoffersen, Reference Hansen and Kristoffersen2016; de Jonge et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Hoenders, Evans-Lacko, Kovess-Masfety, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Bunting, Caldas-de-Almeida, Dinolova, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Huang, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lépine, Levinson, Makanjuola, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Scott, Tachimori, Williams, Wojtyniak, Kessler and Thornicroft2018; Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues, Reference Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues2022; Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues, Reference Faisal-Cury and de Oliveira Rodrigues2022). A WHO study (de Jonge et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Hoenders, Evans-Lacko, Kovess-Masfety, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Bunting, Caldas-de-Almeida, Dinolova, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Huang, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lépine, Levinson, Makanjuola, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Scott, Tachimori, Williams, Wojtyniak, Kessler and Thornicroft2018) observed that approximately 4% of patients diagnosed with mental disorders in populational studies sought care from a CAM professional in the last 12 months, ranging from 2% in underdeveloped countries and 5% in developed countries. In this study, 8–18% of patients using traditional treatments also use CAM. Relating to psychiatric disorders, 30% of patients who used CAM had mood or anxiety disorders.

Unützer et al. (Reference Unützer, Klap, Sturm, Young, Marmon, Shatkin and Wells2000) found that 23% of CAM users have mental disorders. In this study, patients with panic disorder, major depression, and generalised anxiety disorder are more likely to use CAM. Along these lines, Hansen and Kristoffersen (Reference Hansen and Kristoffersen2016) reported that 18% of patients who reported anxiety or depression sought alternative treatments in the previous year, more frequently by women and people with greater education. General anxiety disorder (15%) and major depression (24%) were associated with CAM use (Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Nortje, Makanjuola, Oladeji, Seedat and Jenkins2015). Anxiety and depression were also associated with the use of CAM in the general population (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Kessler, Foster, Norlock, Calkins and Delbanco1993, 1998).

In a national survey in the USA, more than half of participants with self-reported ‘anxiety attacks’ and ‘severe depression’ used CAM in the past 12 months. Moreover, 25–30% of these CAM users with anxiety/ depression visit a psychiatrist (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Soukup, Davis, Foster, Wilkey, Van Rompay and Eisenberg2001). Druss and Rosenheck (Reference Druss and Rosenheck2000) observed that almost 10% of psychiatric patients visit a CAM service. This search for CAM was higher for patients with anxiety (adjustment disorder or transient stress), substance use disorders, and affective disorders. Near half of them used CAM for their psychiatric condition. Herbal medicines were used by 29% of these patients. In the same line, Knaudt et al. (Reference Knaudt, Connor, Weisler, Churchill and Davidson1999) found that 54% of psychiatric outpatients in an anxiety and stress programme used CAM.

It was suggested that 1 out of 7 patients with severe mood disorders (14%), 1 out of 6 with severe anxiety (16%), and 1 out of 4–5 with severe behavioural disorders (22%) visit a CAM provider (de Jonge et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Hoenders, Evans-Lacko, Kovess-Masfety, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Bunting, Caldas-de-Almeida, Dinolova, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Huang, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lépine, Levinson, Makanjuola, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Scott, Tachimori, Williams, Wojtyniak, Kessler and Thornicroft2018). Knaudt et al. (Reference Knaudt, Connor, Weisler, Churchill and Davidson1999) observed that phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines were the most frequently CAM used by psychiatric outpatients.

Phytotherapy

Independently of the CAM definition employed in the above studies, all included phytotherapy. In this line, Kessler et al. (Reference Kessler, Soukup, Davis, Foster, Wilkey, Van Rompay and Eisenberg2001) observed that patients with anxiety or depression used phytotherapy (7 and 9%, respectively).

Reviewing studies reporting the use of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicine in adults suffering from anxiety, McIntyre et al. (Reference McIntyre, Saliba, Wiener and Sarris2015) observed that 2–22% of adults used it, mainly those with generalised anxiety disorder diagnosis. The beliefs cited for this use were: holism, faith in natural treatments, and personal control over health.

In the USA, around 40% who used phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines used concurrently conventional medications (Rashrash et al., Reference Rashrash, Schommer and Brown2017). Among women with depression, 20% used phytotherapeutics/herbal medicine in the last 12 months, and 54 reported using CAM in this time frame (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fuller, Liu, Lee, Fan, Hoven, Mandell, Wade and Kronenberg2007). It is observed that acutely hospitalised psychiatric patients also showed substantial use of herbal medicines (44%) in the previous 12 months (Elkins et al., Reference Elkins, Rajab and Marcus2005), while 63% of psychiatric outpatients used CAM in the last year (Knaudt et al., Reference Knaudt, Connor, Weisler, Churchill and Davidson1999).

It is important to highlight that nowadays there is a growing interest in phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines for neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, Cannabis and its derivates (e.g. cannabidiol), and lavender essential oil are being studied for depression, anxiety disorders, Parkinson’s disease, and autism spectrum disorders, among others (e.g., Crippa et al., Reference Crippa, Guimarães, Campos and Zuardi2018; Sarris, Reference Sarris2018; Sarris et al., Reference Sarris, Ravindran, Yatham, Marx, Rucklidge, McIntyre, Akhondzadeh, Benedetti, Caneo, Cramer, Cribb, de Manincor, Dean, Deslandes, Freeman, Gangadhar, Harvey, Kasper, Lake, Lopresti, Lu, Metri, Mischoulon, Ng, Nishi, Rahimi, Seedat, Sinclair, Su, Zhang and Berk2022; Silva Junior et al., Reference Silva Junior, Medeiros, Torro, Sousa, Almeida, Costa, Pontes, Nunes, Rosa and Albuquerque2022). While for some CAM the high prevalence of its use has relative importance, revealing the patient’s beliefs and attitude towards the disease that can influence their treatment adherence, in the case of phytotherapy/herbal medicine the possibility of pharmacological interactions and adverse effects are added (e.g., Andreatini, Reference Andreatini2000; Druss and Rosenheck, Reference Druss and Rosenheck2000; Agbabiaka et al., Reference Agbabiaka, Wider, Watson and Goodman2017; de Jonge et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Hoenders, Evans-Lacko, Kovess-Masfety, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Bunting, Caldas-de-Almeida, Dinolova, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Huang, Karam, Karam, Lee, Lépine, Levinson, Makanjuola, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Scott, Tachimori, Williams, Wojtyniak, Kessler and Thornicroft2018; Izzo et al., Reference Izzo, Hoon-Kim, Radhakrishnan and Williamson2022; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Marques, Soares, Slomp Junior, Sanches and Mello2023).

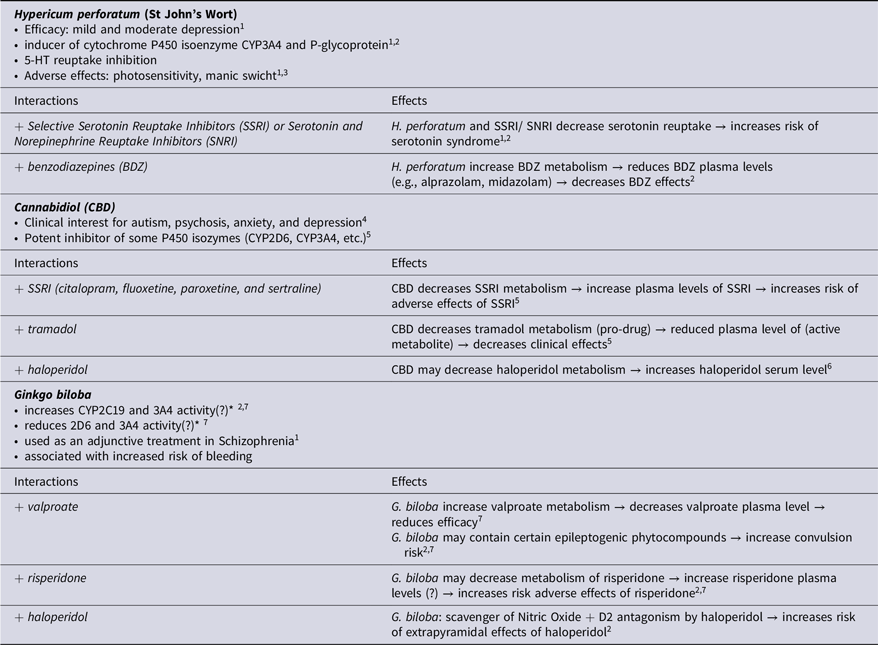

Pharmacological interactions are a crucial point that every physician must be aware of, not only between conventional medicines (e.g., two selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) altogether potentially causing serotonin syndrome) but also possible interactions between certain nutrients (e.g., hypertensive crisis due to association of unspecific monoaminoxidase inhibitors and foods rich in tyramine) and between conventional medicines and phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines. For example, Hypericum perforatum (St Jonh’s wort), which has been used for depression, is an inducer of cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein, which can lead to pharmacokinetics interaction (Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Driver and Baxter2009; Sarris et al., Reference Sarris, Ravindran, Yatham, Marx, Rucklidge, McIntyre, Akhondzadeh, Benedetti, Caneo, Cramer, Cribb, de Manincor, Dean, Deslandes, Freeman, Gangadhar, Harvey, Kasper, Lake, Lopresti, Lu, Metri, Mischoulon, Ng, Nishi, Rahimi, Seedat, Sinclair, Su, Zhang and Berk2022). Moreover, Hypericum perforatum, which inhibits serotonin reuptake, can also interact pharmacodynamically with SSRI and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), potentially inducing serotonin syndrome and has been identified as a trigger for mania in patients with bipolar disorder (Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Driver and Baxter2009; Sarris et al., Reference Sarris, Ravindran, Yatham, Marx, Rucklidge, McIntyre, Akhondzadeh, Benedetti, Caneo, Cramer, Cribb, de Manincor, Dean, Deslandes, Freeman, Gangadhar, Harvey, Kasper, Lake, Lopresti, Lu, Metri, Mischoulon, Ng, Nishi, Rahimi, Seedat, Sinclair, Su, Zhang and Berk2022; Rodrigues Cordeiro et al., Reference Rodrigues Cordeiro, Côrte-Real, Saraiva, Frey, Kapczinski and de Azevedo Cardoso2023). It can be stressed that other medical specialities also prescribe conventional psychopharmacological agents, as neurologists prescribe SNRI for neuropathic pain, and these drugs can potentially interact with phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines used to treat neurological disorders, such as Mucuna pruriens, which contains levodopa, for Parkinson’s Disease (Cilia et al., Reference Cilia, Laguna, Cassani, Cereda, Pozzi, Isaias, Contin, Barichella and Pezzoli2017; Kamkaen et al., Reference Kamkaen, Chittasupho, Vorarat, Tadtong, Phrompittayarat, Okonogi and Kwankhao2022; Soto-Lara et al., Reference Soto-Lara, Silva-Loredo, Monroy-Córdoba, Flores-Ordoñez, Cervera-Delgadillo and Carrillo-Mora2023). This also could occur with other natural products, such as omega-3 fatty acids (‘fish oil’), which showed some antidepressant effects when added to conventional antidepressants (e.g., da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Munhoz, Alvarez, Naliwaiko, Kiss, Andreatini and Ferraz2008; Sarris et al., Reference Sarris, Ravindran, Yatham, Marx, Rucklidge, McIntyre, Akhondzadeh, Benedetti, Caneo, Cramer, Cribb, de Manincor, Dean, Deslandes, Freeman, Gangadhar, Harvey, Kasper, Lake, Lopresti, Lu, Metri, Mischoulon, Ng, Nishi, Rahimi, Seedat, Sinclair, Su, Zhang and Berk2022). Table 1 gives some examples of potential drug-herb interactions and adverse effects related to phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines.

Table 1. Examples of drug-herbal medicines interactions and adverse effects of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines

2 Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Driver and Baxter2009

3 Rodrigues Cordeiro et al., Reference Rodrigues Cordeiro, Côrte-Real, Saraiva, Frey, Kapczinski and de Azevedo Cardoso2023

4 Bonaccorso et al., Reference Bonaccorso, Ricciardi, Zangani, Chiappini and Schifano2019

5 Wilson-Markeh et al., Reference Wilson-Morkeh, Al-Abdulla, Sien, Mohamed and Youngstein2020

6 Balachandran et al., Reference Balachandran, Elsohly and Hill2021

7 Le et al., Reference Le, McGrath and Fasinu2022

* Both effects were described.

These problems with herbal medicines can be magnified in some special populations. For example, older patients, who have a significant prevalence of concurrent use of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines and conventional medicines (e.g. beta-blockers, diuretics, anticoagulants/ antiaggregant, and statins) (Agbabiaka et al., Reference Agbabiaka, Wider, Watson and Goodman2017). Under the wrong belief that ‘what is natural is safe’, some women patients prefer to use phytotherapy during pregnancy and/or breastfeeding, avoiding, or reducing the use of conventional drugs (Sarris et al., Reference Sarris, Ravindran, Yatham, Marx, Rucklidge, McIntyre, Akhondzadeh, Benedetti, Caneo, Cramer, Cribb, de Manincor, Dean, Deslandes, Freeman, Gangadhar, Harvey, Kasper, Lake, Lopresti, Lu, Metri, Mischoulon, Ng, Nishi, Rahimi, Seedat, Sinclair, Su, Zhang and Berk2022).

Additional questions about the use of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines may arise from technical issues relating to product manufacturing without adequate quality assurance practices, such as contamination (e.g. pesticide residues, impurities, etc.), plant substitution or misidentifications, among others (Sarris et al., Reference Sarris, Ravindran, Yatham, Marx, Rucklidge, McIntyre, Akhondzadeh, Benedetti, Caneo, Cramer, Cribb, de Manincor, Dean, Deslandes, Freeman, Gangadhar, Harvey, Kasper, Lake, Lopresti, Lu, Metri, Mischoulon, Ng, Nishi, Rahimi, Seedat, Sinclair, Su, Zhang and Berk2022). Moreover, it is important to consider the method for product standardisation and the constituent used as a marker, which can result in different extracts of the same plant containing different compounds/ compounds concentrations, changing their efficacy, adverse effects, and pharmacological interactions.

The use of CAM is underreported by the patient and/or not questioned by the consulting physician/psychiatrist

Some of these studies about CAM use also indicate that most patients who use CAM do not tell their physician (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Kessler, Foster, Norlock, Calkins and Delbanco1993, Reference Eisenberg, Kessler, Foster, Norlock, Calkins and Delbanco1996; Knaudt et al., Reference Knaudt, Connor, Weisler, Churchill and Davidson1999; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Jones, Evans and Leslie2012; Agbabiaka et al., Reference Agbabiaka, Wider, Watson and Goodman2017). For example, Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Jones, Evans and Leslie2012) observed that around 60% of CAM users did not inform their doctor about their use. This also appears to apply to phytotherapy, since 86% of users of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines in United Kingdon did not discuss their use with their doctors (Posadzki et al., Reference Posadzki, Watson, Alotaibi and Ernst2013). These data agree with Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Marques, Soares, Slomp Junior, Sanches and Mello2023) who observed that 74% of physicians training for Family and Community programme did not ask if their patients are using phytotherapy. Considering that CAM has a significant prevalence of use worldwide, it is probable that this use by psychiatric patients may occur without the knowledge of the patient’s psychiatrist. This hypothesis is corroborated by some studies with psychiatric patients (Druss and Rosenheck, Reference Druss and Rosenheck2000; Posadzki et al., Reference Posadzki, Watson, Alotaibi and Ernst2013). This also applies to inpatients hospitalised for acute psychiatric disorders, of whom only 21% referred their use of CAM to their psychiatrists (Elkins et al., Reference Elkins, Rajab and Marcus2005).

This is an important issue since some CAM (e.g. phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines) could exert adverse events or drug interactions, as discussed above, and psychiatrists may have difficulties identifying these situations without the information about CAM use.

Discussion

The studies reviewed indicate a significant prevalence of CAM use, including phytotherapy, in the general population and psychiatric patients. Furthermore, more than half of these patients did not discuss this with their physician or psychiatrist. As stressed by Walter and Rey (Reference Walter and Rey1999), psychiatrists should not be naïve and think that their patients do not try other treatments, that CAM does not exist, or that all CAM studies are flawed.

Particularly concerning phytotherapy/herbal medicine, it has been used by a substantial part of psychiatric patients. This can impact the patient’s clinical evolution in several aspects. For example, the use of inefficacious phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines may delay the search for appropriate treatment, which can worsen the clinical condition. On the other hand, the use of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines with clinical efficacy can contribute to clinical improvement, which may be erroneously attributed to a conventional medication alone. Moreover, rejecting or ignoring effective phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines could deprive the patient of an effective option for her/his treatment. Other aspects, as discussed above, could be pharmacological interactions, adverse effects, and toxicity.

Therefore, psychiatrists must have adequate and up-to-date knowledge about phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines for better treatment of psychiatric patients (Walter and Rey, Reference Walter and Rey1999; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fuller, Liu, Lee, Fan, Hoven, Mandell, Wade and Kronenberg2007) as well as in other medical specialties, as neurologists (Le et al., Reference Le, McGrath and Fasinu2022; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Marques, Soares, Slomp Junior, Sanches and Mello2023). This knowledge also helps health professionals, including psychiatrists, who are employing conventional medicine, to understand better the health-related practices of their patients and improve their communications with them (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fuller, Liu, Lee, Fan, Hoven, Mandell, Wade and Kronenberg2007).

In this line, it is important to educate and raise awareness among psychiatrists about phytotherapy/herbal medicines to improve patient health, expand patients’ therapeutic options, but also avoiding the use of ineffective phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines, and minimise the risks and adverse effects of using effective phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines. Unfortunately, this topic is absent in most books, articles, and guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of psychiatric disorders, making it difficult to provide adequate information for psychiatrists and to include the use (or not) of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines in the anamnesis and routine clinical practice. For example, more than 80% of physician trainees in family and community medical programme did not receive any information about phytotherapy (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Marques, Soares, Slomp Junior, Sanches and Mello2023).

However, this education is also impaired by the scarce data about the use of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines by psychiatric patients. Therefore, the assessment of the frequency of use of CAM, their causes, their evaluation by the attending psychiatrist, and their importance for the psychiatrist-patient relationship are aspects that need to be studied.

In this line, more than 20 years ago, Walter and Rey (Reference Walter and Rey1999) posed some interesting questions that were not adequately addressed yet: (1) Should psychiatrists discuss with their patients, indicate, or support phytotherapy/herbal medicine that showed clinical efficacy in controlled clinical trials? (2) Should phytotherapy/herbal medicine be discussed/ taught among biological treatments to undergraduate medical students and psychiatric interns? (3) Are psychiatrists prepared to work in association with phytotherapists?

Similarly, Yager et al. (Reference Yager, Siegfreid and DiMatteo1999) proposed some guidelines for psychiatrists regarding CAM and phytotherapeutics/herbal medicine: (1) routinely question patients about CAM; (2) discuss with their patients about safety and efficacy; (3) discuss the benefits and harms of alternative treatments with their patients; (4) provide adequate and up-to-date information about CAM for their patients; (5) and learn about alternative therapies (knowing where to find evidence-based information about them).

It is important to highlight that several authors have proposed that questions regarding the use of CAM should be routinely asked by psychiatrists to their patients (Walter and Rey, Reference Walter and Rey1999; Unützer et al., Reference Unützer, Klap, Sturm, Young, Marmon, Shatkin and Wells2000; Elkins et al., Reference Elkins, Rajab and Marcus2005; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Jones, Evans and Leslie2012; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Marques, Soares, Slomp Junior, Sanches and Mello2023).

Based on the above considerations, some recommendations can be made:

Stimulate studies evaluating the use of phytotherapy/herbal medicines by psychiatric patients using similar methodologies (e.g., standardised questionaries or interviews both for psychiatric diagnosis and CAM use, as I-CAM to detect CAM/ phytotherapy use) and done in different settings (e.g., outpatients, inpatients).

The inclusion of phytotherapy theme in the medical curriculum, books, articles, and events about drug treatment of psychiatric disorders, discussing its efficacy (and inefficacy), mechanisms of action, adverse effects, and drug interactions.

Teaching principles and clinical aspects of phytotherapeutics/herbal medicine to undergraduate medical students and trainees/ interns in psychiatry.

Inclusion of questions regarding phytotherapeutics/herbal medicines use in the routine psychiatric clinical interview.

Conclusion

In conclusion, psychiatrists should keep in mind that there is a high likelihood that their patients are using phytotherapy and should ask routinely about this use. Moreover, more emphasis should be placed on the education of medical professionals (including psychiatrists) about phytotherapy.

Author contributions

R. Andreatini, JCF Galduróz: conceptualisation, writing – original draft, review, and editing.

G.F.M. Lacerda, H. Slomp Júnior, MABF Vital: conceptualisation, writing – review, and editing.

P.C. Oliveira: writing – review and editing.

Financial support

MABFV and JCFG are recipients of CNPq research fellowships.

Competing interests

None.