PARTICIPATORY SITE STEWARDSHIP AS A COMPLEX AND EVOLVING SCENARIO

For decades, the Gold Rush town of Bodie has been a popular destination, visited by more than 100,000 visitors annually since 1990 (DeLyser Reference DeLyser1999). Between 2011 and 2014, visitor counts increased steadily at a rate of an additional 1,000 visitors each year, a trend that has continued into recent years (DPR 2018; Figure 1). Although most visitors tend to focus on Bodie's 150 remaining structures, the built environment that exists today represents only 10% of the original 1870s settlement (Anthropological Studies Center 2015; Figure 2a).

FIGURE 1. (a) Annual total visitation 2011–2018 and (b) monthly average visitation 2011–2018 at Bodie using data collected via DPR449 Form (Bodie State Historic Park Monthly Visitor Attendance Reports). Visitation data for April, May, October, and December 2015 is missing or was not recorded.

FIGURE 2. (a) Drone-based view of the core of Bodie townsite, (b) view of the Standard Stamp Mill and nearby wooden structures on the hillside, and (c) view of remains associated with mining activities near the Roseclip Mine located in a hazardous zone closed to the public. Photograph (a) by Nicola Lercari; photographs (b) and (c) courtesy of Anaïs Guillem.

Like many sites of cultural significance, most of the information about Bodie exists in the form of scattered archaeological artifacts that, together with other features and ruins, collectively tell the stories of its past inhabitants. Evidence of Bodie's past, however, is fast deteriorating because of the site's increasing popularity. Visitors regularly remove objects from their original contexts, either taking them home as souvenirs or bringing them to park staff because they are concerned about the items disappearing. These actions incrementally remove important pieces of Bodie's history, limiting our understanding of its past community and former residents. Moreover, prolonged drought, related wildfires, and a series of earthquakes in recent years have further exacerbated the site's preservation, sustainability, and resilience issues.

These conservation concerns compound the complexities of balancing cultural tourism at Bodie and protecting its resources for generations to come, which is a ubiquitous problem affecting the management of sites of cultural significance worldwide.

We argue that citizen science and mobile apps specifically designed for site stewardship are viable tools for alleviating negative human impacts on cultural landscapes and enhancing our capacity to record and monitor sites of cultural heritage. To further the preservation and educational goals for sites and parks, in this study we apply the above-mentioned principles through the creation of the Citizen Preservationist (CitPres) app. CitPres is an open-source hybrid mobile/desktop software that can be utilized to engage visitors with training on the importance of preservation in place and community participation in site investigation and monitoring.

CITIZEN SCIENCE AS A TOOL FOR THE STUDY AND PRESERVATION OF THE PAST

Citizen science is a method of scientific inquiry in which a group of nonprofessional scientists volunteers time and effort in data collection, analysis, and dissemination at a scale that is not viable in traditional research (Haklay Reference Haklay, Sui, Elwood and Goodchild2013:106). The recent exponential growth in the number and scope of citizen science projects has been attributed to the increasing availability and affordability of mobile internet connections and location-aware devices that have enabled citizen scientists to collect field data that otherwise would be too time intensive, expensive, or outright impossible to research (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Mankoff and Paulos2013; Pew Research Center 2019; Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project 2019).

Archaeological and heritage preservation projects have positively implemented citizen science and participatory activities to expand existing commitments to volunteer-based data collection and public engagement. Smith (Reference Smith2014:754–757) has identified four key spheres of application:

(1) Large-scale participatory fieldwork research or mass heritage surveying/recording initiatives, including the numerous site stewardship programs developed by universities, nonprofit organizations and public agencies, such as the Arizona Site Stewards Volunteer Program, Nevada Site Stewardship Program, California Archaeological Site Stewardship Program, Texas Archeological Stewards, Maine Midden Minders, and Heritage Monitoring Scouts (HMS Florida) projects in the United States (Kelly Reference Kelly2007; Musser-Lopez Reference Musser-Lopez2010); the Rock Art CARE, Portable Antiquities Scheme , and CITiZAN projects and the SCAPE Trust in the United Kingdom; or the various coastal archaeology programs that have worked with nonprofessional divers or beach visitors to conduct shoreline surveys and report on the state of preservation of underwater remains or the opportunistic exposure of shipwrecks (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Hambly, Kelley, Lees and Miller2020; Scott-Ireton and Moates Reference Scott-Ireton, Moates, Jameson and Musteață2019).

(2) Web-based crowdsourced analysis, such as the web platforms GlobalXplorer and TerraWatchers, which enable remote discovery of archaeological sites or the monitoring of at-risk cultural heritage in case of conflict, looting, or other anthropogenic hazards (Parcak Reference Parcak2019:219–222; Savage et al. Reference Savage, Johnson, Levy, Vincent, López-Menchero Bendicho, Ioannides and Levy2017), or Heritage Quest, which leverages crowd analysis of lidar data for site reconnaissance in forested landscapes.

(3) Archaeological research enabled by crowdfunding, consisting of numerous archaeological projects worldwide receiving micro-donations through citizen science platforms, such as Experiment, SciStarter, and Zooniverse; or purpose-built archaeological crowdfunding platforms, such as Crowdfunding for Archaeology and DigVentures (Piscitelli Reference Piscitelli2013).

(4) Crowdsourced creation or annotation of digital collections and repositories of geotemporal, archaeological, cultural, and curatorial data in the cloud, such as ARIADNEplus, the Finnish Archaeological Finds Recording Linked Open Database (SuALT), MicroPasts, Pleiades, Google Ancient Places, and Recogito projects among many others (Bagnall et al. Reference Bagnall, Talbert, Bond, Becker, Elliott, Gillies, Horne, McCormick, Rabinowitz, Robinson and Turner2006; Harris Reference Harris2012; Kansa Reference Kansa2012; Simon et al. Reference Simon, Barker, Isaksen and De Soto Cañamares2017:20).

SITE STEWARDSHIP AND CITIZEN SCIENCE: COMMON GOALS AND PROBLEMATICS

Even though citizen science presents numerous benefits to site preservation and appreciation, enlisting casual visitors in participatory site stewardship activities inherently introduces potential issues for the protection of sites. A major risk is that governmental agencies entrusted with managing sites may see this approach as a way to “outsource” preservation activities to the goodwill of local organizations or citizens in order to save money and/or address government funding shortfalls. To mitigate this problem, academics, heritage professionals, and other local stakeholders involved in implementing site stewardship through mobile-app-based citizen science need to assess the effects of their initiatives, making adjustments and changes as needed, and ensure that the proposed community-based participatory frameworks are not leveraged negatively (Adair et al. Reference Adair, Filene and Koloski2011; Atalay Reference Atalay2012; Frisch Reference Frisch2003; High Reference High2009). Therefore, we believe that mobile-app-based citizen science must be used as a tool to increase cooperation between archaeologists, preservation specialists, park managers, community organizations, and visitors, which has long been identified as a priority by disciplinary experts and preservation professionals (Matero et al. Reference Matero, Fong, Del Bono, Goodman, Kopelson, McVey, Sloop and Turton1998).

Additionally, asking casual visitors to record and monitor surface artifacts may prove problematic because it might encourage visitors to remove objects from their original contexts and increase illicit collection. Although this is a legitimate concern, we must also acknowledge that this issue is neither a direct consequence of citizen science nor the usage of mobile apps. It is instead a long-lived and ongoing problem affecting sites large and small where visitors can roam freely and interact with objects and buildings scattered through the cultural landscape. Significantly, the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) project, initiated in England and Wales in the mid-1990s, has successfully tackled this issue by bringing together archaeologists and the public to record archaeological finds, de facto spearheading participatory heritage management through education (Bland Reference Bland2009; Lewis Reference Lewis2016). Similarly, the LEARN Archaeology Expedition Program has provided best practices for training the visiting public on the importance of site preservation, context, and object curation (Reeves Reference Reeves2015). These initiatives have demonstrated that utilizing a team-based approach in which participants use their devices (e.g., a metal detector or cell phone) to conduct site stewardship increases the success of citizen science in archaeology. We therefore argue that, instead of working retroactively to mitigate artifact loss, site managers should allow the very people who travel to enjoy an archaeological site or historic park to participate and become educated in its preservation using citizen science.

A final consideration regarding the implementation of the proposed approach is related to uninformed visitors potentially engaging in erroneous observations and introduce poor-quality data on artifacts’ material, size, and state of preservation to our database. Previous studies have emphasized verification of crowdsourced data collection and analysis and indicate that for citizen science to be a viable research tool, multiple layers of control must be in place (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Allee, Brown, Losey, Roy and Smyth2012:472–475; Lintott et al. Reference Lintott, Schawinski, Slosar, Land, Bamford, Thomas, Jordan Raddick, Nichol, Szalay, Andreescu, Murray and Vandenberg2008; Maisonneuve and Chopard Reference Maisonneuve, Chopard, Xiao, Kwan, Goodchild and Shekhar2012:121–123; Savage et al. Reference Savage, Johnson, Levy, Vincent, López-Menchero Bendicho, Ioannides and Levy2017:69–73; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Aycrigg, Barry, Bonney, Bruns, Cooper, Damoulas, Dhondt, Dietterich, Farnsworth, Fink, Fitzpatrick, Fredericks, Gerbracht, Gomes, Hochachka, Iliff, Lagoze, La Sorte, Merrifield, Morris, Phillips, Reynolds, Rodewald, Rosenberg, Trautmann, Wiggins, Winkler, Wong, Wood, Yu and Kelling2014:2284–2285). The issue of data accuracy, standardization, and quality can be solved in mobile-based citizen science by enforcing mandatory user training, conducted either in person by local staff or via in-app video tutorials before users can begin collecting data. In-app data entry forms that include drop-down menus and instantaneous filtering can be used to minimize errors (e.g., any record where an artifact is recoded being larger than a specific size triggers a warning and precludes users from saving the data). Additional quality control methods include requiring users to complete data review before an observation is saved and having domain experts and trained algorithms conduct post-collection validation before final data curation.

We believe that the above strategies make a strong argument for mobile-app-enabled citizen science to become fully operational at sites of cultural significance. This allows staff to use the digital tools and datasets made possible by citizen science to conduct periodic site monitoring and rapidly intervene and take measures to protect an archaeologically significant area, a cluster of artifacts, or individual objects.

SITE AND RESEARCH BACKGROUND

The Gold Rush town of Bodie is a significant site of state and national heritage, considered the “finest example of a mining ghost town in the West” (Snell Reference Snell1964:2). Bodie was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1961, and it became a California State Historic Park in 1962 (Felton et al. Reference Felton, Lortie, Davis and Lewis1977). The park is located on the western boundary of the Great Basin Region (Figure 3), a vast hydrographic area in the arid western United States (Grayson Reference Grayson2006), and it encompasses a 2,900-acre historical landscape dotted with reminders of an industrial era long since abandoned (ca. 1859–1942).

FIGURE 3. Map of eastern California showing Bodie's location in relation to the hydrographic Great Basin Region and the western United States. Map courtesy of Manuel Dueñas Garcia.

Industrial remains, including mine shafts, tunnels, waste rock dumps, mill sites, tailings ponds, habitation sites, and other structures and objects, cover the hillsides (Figures 2b and 2c, above). The core of the Bodie townsite, as well as the surrounding mining zone, contain hundreds of ruins in the form of collapsed wooden buildings, cellar pits, privy holes, dumps, and broadcast refuse, which constituted the commercial and residential remains of the district's 7,000–8,000 former inhabitants (Piatt Reference Piatt2003:44).

Bodie still exists today in large part due to the guardianship of the J. S. Cain Company, a family-owned enterprise that purchased many of the abandoned buildings and lots in and around the town (Cain Reference Cain1956:75–88). A caretaker for the company protected the remaining buildings from looters and vandals during periods of low mining and exploration activity between the 1930s and 1950s. Despite their efforts, the J. S. Cain Company and CSP, which acquired Bodie in the early 1960s, could not prevent the illicit collection of artifacts large and small (DPR 1960), and this issue has persisted to the present day. Therefore, it has become a high priority for CSP and the Bodie Foundation to develop new and effective digital preservation methods that not only allow amassing comprehensive geospatial data of Bodie in case the site is damaged or destroyed in the future but that also enhance recording and monitoring of surface artifacts in ways that do not limit access to popular locations and iconic buildings within the park.

Between 2015 and 2017, as part of the Bodie 3D Project, we partnered with CSP to collect comprehensive geospatial data utilizing both terrestrial light detection and ranging (t-lidar) and structure from motion (SfM) photogrammetry. We generated ultra-precise measurements and 3D models that can be used to inform future studies, conservation efforts, or physical reconstruction of the site (Lercari and Jaffke Reference Lercari and Jaffke2017). More specifically, we flew an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) over the entire townsite and recorded hundreds of close-range photographs and several 4K-resolution videos. We also used t-lidar to document with high accuracy and precision eight historic buildings, including the iconic Dechambeau Hotel, Hoover House, Railroad Depot, two buildings associated with mining operations, and the residences of a Chinese family and Native American family. We shared results with park managers and created a best-practice guide for built heritage documentation that was reviewed and accepted by California State Parks as the standard operating procedure for the department (Lercari and UC Merced HIVE Lab Reference Lercari2017).

We are aware, however, that to develop a viable and sustainable site stewardship program at Bodie, continuous and large-scale monitoring of buildings and archaeological remains must be implemented by engaging park visitors as partners. Consequently, we implemented solutions to the challenge of balancing preservation and current use by developing a mobile-app-based enhanced version of citizen science that involves the public in on-site training and collaborative recording and monitoring of the archaeological remains that define Bodie's cultural landscape. In 2019, we developed and field-tested the CitPres app with the intention of engaging an initial group of volunteers/beta testers in crowdsourced data capture and geospatial visualization of scattered artifacts. We contend that the significance of the proposed approach derives from the CitPres app's unique ability to address the complexities of site preservation and conservation through community participation as well as its broad applicability at a variety of sites of cultural significance. To allow other scholars and heritage practitioners to test, verify, customize, and reuse the CitPres app, we released our software into the public domain via GitHub.

METHODS

Implementing Site Stewardship through the Citizen Preservationist App and On-Site Training

The CitPres app is significant because it can be utilized to engage volunteers with documenting, monitoring, and visualizing surface artifacts at any site where the local staff is willing to partner with casual visitors to collectively preserve the cultural landscape (Figures 4a and 4b).

FIGURE 4. (a) Cluster of artifacts in their original context, (b) citizen preservationist using the CitPres app in 2019, (c) screenshot of the photo feature in the CitPres DataCollector app, and (d) screenshot of the photo review feature in the DataCollector app. Photographs by Nicola Lercari.

Our software supports both opportunistic data collection in the field and subsequent visual analysis through the following components:

(1) CitPres DataCollector is a mobile app for the documentation of archaeological artifacts developed in Unity 3D using both custom C# code and Unity core functionalities. It features a high-contrast user interface to optimize outdoor use, photo taking, video training, and metadata recording capabilities.

(2) CitPres Map is a desktop app developed in Unity for rapidly ingesting photographs, geospatial data, and metadata produced by our DataCollector that enables interactive data visualization through a monitor, TV, or touch display. The advantage of developing our software in Unity is that this cross-platform development ecosystem provided us with the financial and structural efficiency of building a single version of each component of the app and then making it easily available to multiple operating systems (i.e., Android and iOS in the case of DataCollector, and Win10 and macOS in the case of Map).

All of CitPres's components can be downloaded from our GitHub repository and then deployed locally with the support of local staff. This approach ensures that CitPres can be used at sites where cell phone coverage or Wi-Fi is unreliable or unavailable. It also allows archaeologists and park managers to have more control over who can use the app and when, which allows them to enforce stricter rules about training users must take before they can start collecting data. More specifically in our case study, required training for volunteers is delivered via in-person sessions—but an in-app video training option is also available for volunteers to review while in the field. Our training focuses on the importance of in situ object collections to reconstruct and preserve the histories and daily lives of Bodie's average resident, which depend on preservation in place. Then, users learn about specific historic archaeology materials at Bodie (i.e., ceramic, fabric, glass, leather, metal, etc.) as opposed to prehistoric materials (i.e., bone, stone, etc.), which would require additional consultation and permission from local tribal partners and governments and which are outside the scope of our study. Additionally, users learn the importance of providing a dimensional reference in the collected data, and they are instructed to carry multiple plastic scales while taking pictures on-site (Figures 4c and 4d).

At any location where CitPres DataCollector is deployed, trained volunteers can explore the site at their own pace and take photos of artifacts they find on the surface. Volunteers are also tasked with describing each photographed artifact directly in the app and adding additional metadata (Figure 5a and 5b, below). The final data-capture step requires volunteers to review, validate, and submit each record (Figures 5c and 5d). After this step is complete, our DataCollector securely stores the photos and metadata on the device without the need of an internet connection. At the end of each data collection session, volunteers must report back to local staff, who collect and ingest recorded pictures and metadata into a local geographic information system (GIS) or database of surface artifacts.

FIGURE 5. Screenshots of the DataCollector app displaying (a) filled-out welcome page showing volunteer ID and place name, (b) video training page, (c) empty data entry form, (d) data entry form showing material drop-down menu, (e) data entry form showing artifact type drop-down menu, (f) data entry form showing artifact category drop-down menu, (g) metadata review page, and (h) data-saving confirmation page.

Data Entry Form, Metadata, and Geotagging

CitPres DataCollector facilitates artifacts’ description through an in-app data entry form consisting of several drop-down menus that ensures standardization for most of the metadata and minimizes errors (Figure 5). To ensure data conformance with widely adopted standards for artifacts from the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century, we utilized fields, categories, and terminology listed in the Sonoma Historic Artifact Research Database (SHARD; Gibson and Praetzellis Reference Gibson and Praetzellis2009). Additionally, our app features metadata elements codified by the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) to ensure easier ingestion in digital asset management and curation platforms such as Nuxeo or long-term preservation in online repositories. Importantly, the DataCollector's entry form and metadata schema can be customized to any specific case study by modifying the app's source code in Unity. Table 1 lists the metadata elements we used at Bodie.

Table 1. List of the SHARD, Dublin Core, and Nuxeo Metadata Elements Used in CitPres DataCollector.

Most significantly, to support preservation in place, CitPres DataCollector geotags and dates the collected photos. To ensure confidentiality, an artifact's location and metadata are recorded in a JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) file not visible to the users. At any time, local staff can bulk download these JSON files organized by the recording date. Each JSON includes a binary version of the artifact's photograph as well as metadata. Recordings can then be batch converted into images (e.g., JPEG) and spreadsheets (e.g., CSV) using our Convert and Save Python script, which is also downloadable from our GitHub. After the conversion is completed, local staff can analyze the collected data using a GIS or our CitPres Map desktop application. Volunteers can keep copies of the photos in their own device's default picture gallery, but any location data or metadata is excluded.

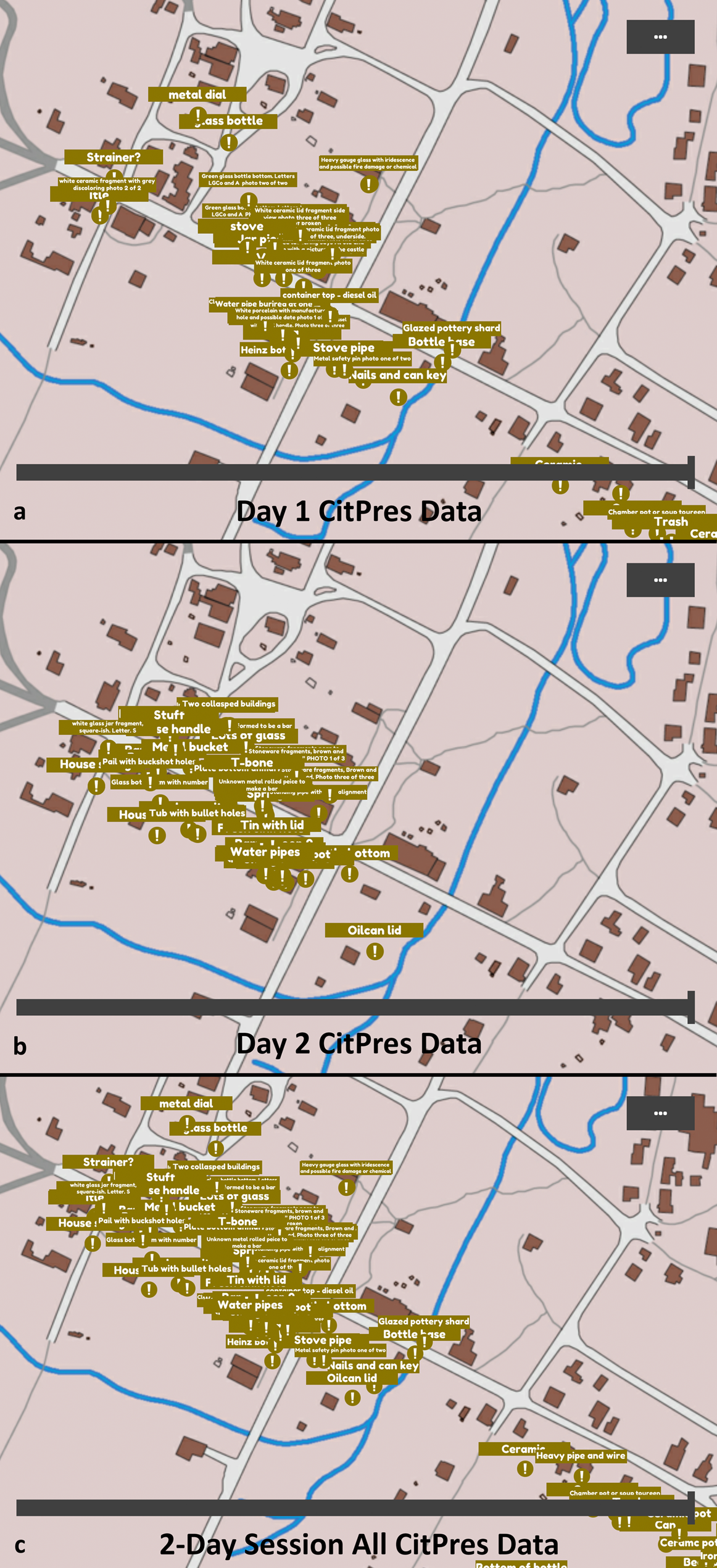

Through the Convert and Save script and CitPres Map app, we aim to provide archaeologists and preservationists with viable tools to create a geodatabase that grows through time and records a dynamic map of a site's cultural landscape, made possible through the analysis of the data captured by citizen preservationists (Figures 6a–6c). Significantly for participatory site stewardship, CitPres Map can be also used for public-facing visualization and outreach at a site's visitor center to increase public engagement and potentially recruit new volunteers while protecting the exact position of the artifacts.

FIGURE 6. The CitPres Map desktop application allows park managers, archaeologists, and visitors to visualize data captured via CitPres DataCollector app: (a) shows data collected by citizen preservationists on the first day of a two-day session at Bodie in 2019, (b) shows data collected on the second day, and (c) shows all data collected during the session.

Supplemental Text 1 provides high-level pseudocode as a reader's guide for nonprogrammers to understand the distinct functionalities of the CitPres app.

RESULTS

We conducted beta testing of the CitPres app in the summer of 2018 and verified the viability of the participatory data collection and visualization features. After this research received institutional review board (IRB) approval in 2019, we developed an on-site preservation and awareness program, in collaboration with California State Parks and the CSP Foundation's Volunteer Program, that involved participants in testing the CitPres app and assessing the effectiveness of this initiative.

Participants consented to data capture and survey/focus group activities that were utilized to assess the CitPres app and the on-site training. Ten volunteers were randomly recruited via the CSP Foundation's website. They participated in a two-day program that tasked citizen preservationists with surveying a portion of the Bodie townsite and collecting data using our app (Figure 6). All participants were 18 years old or older. None were professional archaeologists or heritage practitioners, but all expressed great interest in California heritage and site stewardship. Notably, six participants had previously attended other site stewardship activities organized by our partners with the CSP Foundation.

The objectives of this initiative were twofold. First, we intended to evaluate public perceptions of active stewardship and protection of Bodie's cultural landscape. Second, we tested the CitPres app for overall performance and utility. The results of an end-of-program assessment conducted using group interviews and written surveys are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. List of Questions Used to Assess the Site Stewardship Program and CitPres with Selected Responses.

DISCUSSION

Although limited in scope and not statistically significant, the responses collected from user study participants in 2019 corroborate our claim that the CitPres app has the potential to engage casual visitors, enabling them to collect archaeological data and contribute to site preservation (Table 2, Questions 1 and 4). Responses show that, on an individual level, citizen preservationists enjoyed participating in our pilot training program at Bodie and using the CitPres app. Spending time recording artifacts using the app allowed participants to imagine the experiences of people who once lived and worked in this mining town, and volunteers expressed a deeper awareness of the value of archaeology and appreciation for the history its practice conveys.

Although several participants voiced concerns that the app would encourage illegal artifact collection (Table 2, responses to Questions 6 and 8), most expressed overall support and emphasized the benefits of asking visitors to assist with building an archaeological database of the site for future interpretation and monitoring efforts. In most cases, they explicitly stated they felt more personally connected to Bodie after using our DataCollector to collect archaeological data (Table 2, responses to Questions 4 and 6). Importantly, the participatory approach proposed here has the potential to foster a more inclusive way of encouraging the visiting public to explore ethnically diverse histories of the past. Many interpretations of U.S. West mining sites like Bodie have overlooked the experiences of its Chinese, Hispanic, and Native American inhabitants (Table 2, Question 3). When citizen science–based initiatives become available to all visitors, we believe this exposure will present more opportunities to involve participants from diverse backgrounds in exploring the stories about Bodie's past that can usually only be researched and appreciated through direct archaeological investigation.

These observations highlight some of the most important aspects of our approach: making heritage preservation more personal, engaging, and inclusive, along with using readily available technologies, establishes a stronger bond between the public and the cultural and archaeological landscapes we wish to preserve. More broadly, responses show that participants felt a sense of pride knowing that they contributed to the preservation of a significant cultural heritage site. They might share their participation and artifact pictures on social media, which not only informs their friends and family of their trip to the site but also carries the message of site preservation and stewardship beyond the park and its visitors. In other words, inviting the public to participate actively creates a win-win situation for managers and visitors alike.

Furthermore, to make participatory site stewardship more transparent and highlight the value of participants’ contributions, we plan to make the data collected by our volunteers at Bodie publicly available via dynamic visualizations inside the park's visitor center through CitPres Map. Finally, to guarantee use, preservation, and broader access to the data produced by citizen preservationists at Bodie, we are also considering the possibility of publishing a curated digital collection of the site's historical archaeology artifacts collected by our volunteers—including all validated data but the location—in an open access repository such as Calisphere. This is an online gateway to California's digital collections powered by the California Digital Library, which also automatically feeds data into the national online open-access repository of the Digital Public Library of America and which will ultimately guarantee long-term sustainability to our archaeological record.

CONCLUSIONS

This article reviewed the implementation of a pilot outreach and training program focusing on participatory site stewardship at Bodie that uses the Citizen Preservationist app. We demonstrated that the proposed approach plays a vital role in increasing awareness and civic engagement around heritage preservation and helps produce participatory documentation with the goal of monitoring vast cultural landscapes.

The initial field testing of the CitPres app shows that volunteers found our software easy and fun to use, contributing to the app's potential to enable participatory preservation of Bodie's archaeological resources and further application to other sites presenting similar preservation issues. Because the first iteration of our on-site training program with volunteers yielded positive results, we believe that the next step is to further evaluate and optimize the CitPres app by involving a larger number of volunteers at Bodie. Consequently, we are currently developing a partnership with local organizations such as the Tahoe Center of the California Conservation Corps to expand and diversify the pool of interested volunteers and advance our understanding of mobile-app-based citizen science specifically designed for advancing participatory documentation and monitoring of historical archaeology sites.

Our results suggest that visitors can use smartphones loaded with the CitPres DataCollector app to collaborate with park managers and provide an increased number of observations and data at a scale that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to acquire. Therefore, we believe that the proposed approach has the potential to further increase cooperation between archaeologists, park managers, and visitors in reducing the complexities of balancing cultural tourism at Bodie and protecting its resources for generations to come.

We found that the critical component that guarantees the success of the proposed mobile-app-based participatory site stewardship and of any archaeological citizen science project is educating the public about heritage preservation ethics and the methods used by professional and academic archaeologists. It is fundamental that visitors understand the value of archaeological context and preservation in place and the importance of sustainable conservation of a site's cultural landscape to preserve its historic fabric or archaeological signature. Participatory efforts that build a long-term research dataset will create a legacy of information about Bodie that will help future visitors, researchers, and managers to explore, preserve, and interpret this unique site. More broadly, it is hoped that the CitPres app can provide an innovative model for site stewardship and heritage preservation that engages the public in both the preservation and appreciation of cultural heritage sites in the western United States as well as other cultural areas presenting similar issues of illicit artifact collection and complex site monitoring.

Acknowledgments

We thank CSP Sierra District staff Catherine Jones and Josh Heitzmann, the Bodie Foundation, the CSP Foundation volunteers, and field consultant Ken McKowen for providing valuable feedback on our app and citizen science outreach program. We are particularly grateful to CSP Cultural Resources Division staff Kathleen Kennedy for helping to improve our app. We thank Jad Aboulhosn, Michael Ngo, and Tarandeep Singh (HIVE Lab undergraduates) for contributing to software design and development, along with Manuel Dueñas García and Anaïs Guillem (HIVE Lab graduate students); UCM staff Marisol Espino and Jerrold Shiroma for contributing to the best-practice methodology discussed in this work; and Gina Palefsky for editing and proofreading the article. We are immensely grateful to CSP Cultural Resources Division Chief Leslie Hartzell and CSP Architectural Designer Elizabeth Prather for inspiring and guiding our research. This work was supported by the California Department of Parks and Recreation via Work Order #13-203732-00 and supplement Work Order #13-203732-00R3 by the Resources Legacy Fund, California State Parks Initiative (RLF Grant #2013-0387) and by the University of California Office of the President via a CITRIS Seed Grant 2016. Funding sources were not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or decision to submit the article for publication. The authors, UC Merced students, and collaborators were officially authorized to experiment with digital preservation technology, citizen science, and participatory site stewardship at Bodie by the California Department of Parks and Recreation via Standard Agreement #C16E0013.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were presented in this article beyond a selection of participants’ responses listed in Table 2.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2020.29.

Supplemental Text 1. High-level pseudocode for nonprogrammers.