Academics, archaeologists, and anthropologists have long been the accepted authority on the care and control of Native culture and archaeological materials. The perspectives, expertise, and protocols of Native NationsFootnote 1 have rarely been respected and incorporated in research conducted by and at collecting institutions like museums and universities. The central mission of many institutions that hold Native collections is to facilitate access to and learning from the items in their care. Open access and research without regard for the cultural protocols and contexts of affiliated Native Nations reinforce the current power imbalance between those Native Nations and museums and academia. Institutions have the power to support and shift ethical access and research practices through meaningful changes to their policies. This article offers institutions and individual researchers an alternative framework for formalized access and research practices that center and affirm Native sovereignty.

The considerations we present here stem from the Indigenous Collections Care (ICC) Guide, which is currently being created by a working group affiliated with the Indian Arts and Research Center at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The ICC Guide as a reference tool “provides a framework to respect and recenter collections stewardship practices around the needs and knowledge of Indigenous community members” and “serves as a bridge between Indigenous community perspectives and traditional museum collections management practices” (Indigenous Collections Care Working Group 2024). The ICC Working Group comprises 20 professionals, with balanced representation from Native and non-Native museum professionals and academics, Tribal Historic Preservation Officers, museum collections staff, and NAGPRA coordinators. An initial draft was written between 2021 and 2023 and has since been extensively reviewed by more than 75 Native professionals and representatives. The feedback from these reviews has directly shaped the guide’s content and forms the foundation for this article. The ICC Guide will be available for free in 2026 on the website of the Indian Arts and Research Center (IARC; https://sarweb.org/iarc/icc/). This article supplements the part of the ICC Guide that addresses the intersection of ethical research and museums.

Historical collecting practices are built on the foundation of colonization, which separated items from their cultural context though extractive actions. Institutions and collectors mimicked successful collecting strategies such as those for natural history specimens and amassed large assemblages of Native cultural material (Deloria Reference Deloria2018:107; Harjo Reference Harjo1989; Hinsley Reference Hinsley1992; Redman Reference Redman2021; Turner Reference Turner2021). Exhibitions of and research into these Native collections were conducted about communities rather than in consultation with them, establishing the institutions as the experts rather than the Native Nations themselves (Atalay Reference Atalay2012; Lonetree Reference Lonetree2012). Recent federal regulations of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA; Pub.L. 101-601; 25 U.S.C. 3001-3013;104 Stat. 3048-3058) have sought to change this power imbalance for Native ancestral human remains, funerary objects, and cultural items. The Duty of Care provision within the 2024 revised NAGPRA regulations requires institutions to restrict access to cultural items, as defined by the law, for research without “free, prior, and informed consent” (43 CFR §10.1(d)(3)). Consultation is baked into the process, because museums are rarely able to identify cultural items without tribal input. Ideally, the implementation of Duty of Care creates an entry point for Native Nations and institutions to discuss research access protocols and to go further, applying these practices to Native cultural material not subject to NAGPRA.

Ethical and reciprocal research gives all parties an equitable voice in both the design and methodology of research questions. “If archaeology attempts to reconstruct the past, Indigenous archaeology practices work to rebuild a more inclusive past where Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, voices, objects, and ancestors are acknowledged, cared for, and celebrated” (Van Alst and Shield Chief Gover Reference Van Alst and Chief Gover2024:xx). Institutions can create meaningful change by developing policies that step outside the echo chamber of academia and recenter research through relationships with Native Nations. We present guidance on such policy shifts and practical steps that can be taken by both institutions and individual researchers.

Making Collections Available

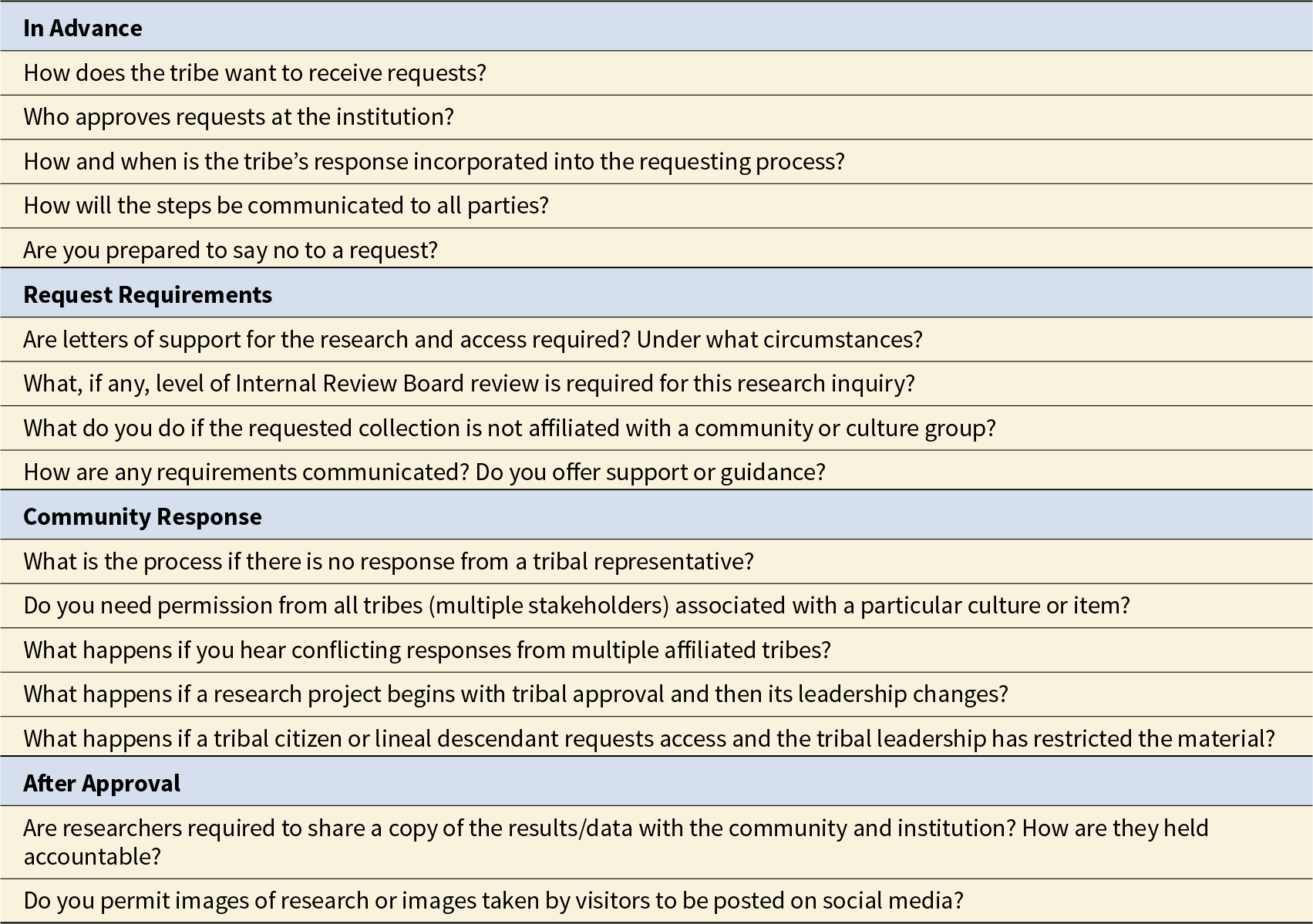

With an institution’s duties to both the public and the Native Nations represented in its collections, how do institutions make Native collections available in legal, respectful, and appropriate ways? Unfortunately, developing a universal standard practice is not feasible. Policy needs vary based on the scope and extent of a collection, an institution’s history and relationships, and the communities and cultures represented within the collection. The guiding questions and considerations in Table 1 aid institutions in determining their priorities and goals, ideally doing so in consultation with appropriate Native Nations. Although each institution and researcher must find their own approach to policy and practice, three guidelines consistently resonate across the board: engage in meaningful consultation with Native Nations, be transparent, and be flexible.

Table 1. Policymaking Considerations.

The following case studies illustrate how different institutions have learned from and responded to experiences related to research on and access to Native collections. The three institutions have very different collections, purposes, and administrative structure. The Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology exists within a private high school and employs collaborative learning to actively engage students, teachers, researchers, and Native Americans with its significant archaeology and anthropology collections. The School for Advanced Research Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) is a research collection and a non-exhibiting institution; its collections are accessed by artists, tribal community members, and researchers. The Gilcrease Museum, a medium-sized museum, focuses on exhibitions and public programs and currently answers to both the City of Tulsa and the University of Tulsa. The events described in the case studies align with and go beyond what is articulated in NAGPRA’s Duty of Care provision. Each institution’s path differs, but the intent and the rebalancing of power and priorities lead to ethical, respectful, and reciprocal research and access policies and practices.

Case Study 1

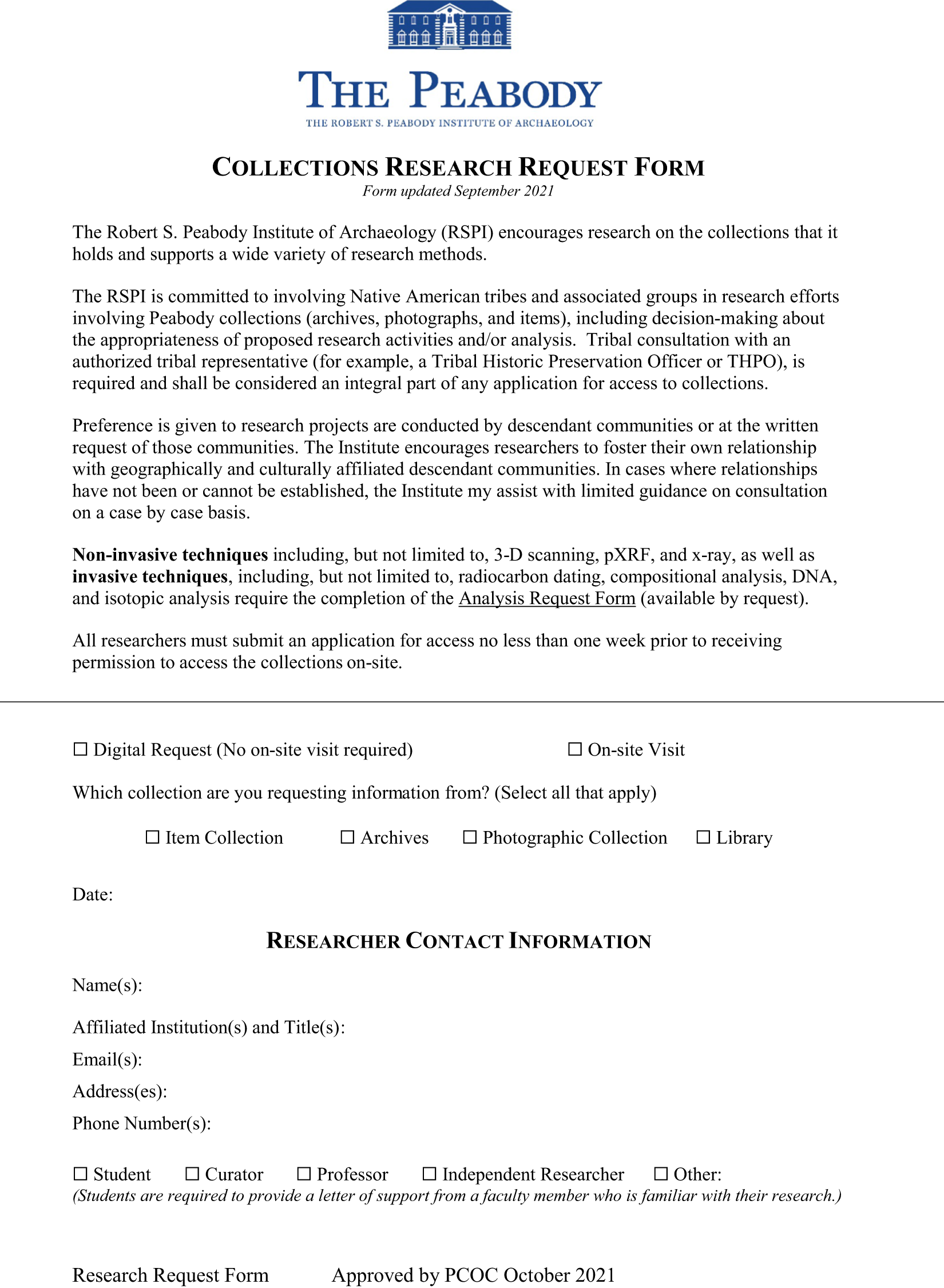

Since 2021, the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology (RSPI) has required a letter of support from the appropriate descendant community before providing research access to any portion of the collection (Taylor Reference Taylor2021). A loophole in the previous policy led to the authorization of inappropriate research and highlighted the need for change.

In 2018, RSPI permitted research on an item from the collection that had been previously identified as outside the scope of NAGPRA. Although all internal policies in place at the time were followed, including a period of review and commentary by an external committee, consultation after the fact revealed that the research was inappropriate. As an article resulting from the research was wending its way toward publication, RSPI hosted multiple consultations between tribal communities and the research team to discuss the issues. These were challenging conversations for everyone involved. The scientists struggled to see why the research was unwelcome, and tribal communities expressed dismay at their lack of involvement in the process. Ultimately, the article was published with a coauthored ethics statement, and all parties agreed that consultation was required prior to any future research.

For RSPI, this was an opportunity to rewrite and reframe all future research requests around the support and participation of Native American communities. Changing the policy to a consent-based approach could not be done without participation from communities that are represented within RSPI’s collection. To make a policy change without that participation would have been a performative act, instead of a collaborative effort to shift decision-making authority around collections research.

An initial draft policy was written by Marla Taylor, the curator of collections at RSPI, and then shared with Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs) of five associated tribal nations for feedback and comments, some of whom had recently expressed concern about the 2018 research. Those comments were then integrated into the policy and research request documentation. A second draft was then shared with researchers who regularly engage with RSPI’s collection for additional comments on the realistic limits to such an approach.

After a final draft (Figure 1) was reshared with the associated THPOs, the policy was presented to the Peabody Collections Oversight Committee (PCOC) for final approval. Although many members of the PCOC were broadly supportive of the change, it was the words of the two THPO representatives on the committee who swayed any skeptics. They spoke passionately about the need for institutions and researchers to prioritize consent and collaboration when working with any Native American archaeological collections and the consequences to communities when they did not. The full process to develop and enact change took about nine months.

Figure 1. Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology research policy and request form.

Case Study 2

At the IARC, collaboration, trust, and respect are the core guiding principles to building relationships with Native communities. Since 2009, it has engaged in an extensive collection review process with multiple communities represented in the collection. A collection review is a systematic review of the entire collection representing one community and can have various outcomes, such as correcting inaccuracies, establishing housing (storage) and handling protocols for every item, and determining publication, photography, and access guidelines for research purposes.

In 2009, the former IARC director, Cynthia Chavez Lamar, contacted the Pueblo of Zuni about a collection of 78 pottery items labeled “Part of the IAF Collection of Zuni Pseudo-Ceremonial Pottery.” Determining whether items were either pseudo-ceremonial or possibly ceremonial would affect access restrictions if research inquiries arose. This initial invitation expanded into a review of the entire collection of 1,100 items from the Pueblo of Zuni. Goals and outcomes were established between the IARC staff and the designated Zuni cultural advisers, and physical reviews continued intermittently for more than six years, with a data review process that followed for an additional three years.

Database fields were repurposed to record whether research access was permitted and to provide a standard for interfacing with shared protocols. The “Tribal Instructions” field indicates the handling, housing (storage), access (research), photography, and publication restrictions that are established by collection review participants for each item. The “Tribal Collection Review Remarks” field adds any notes from the collection review participants during a review, including correcting inaccuracies. Repurposing the database fields may seem overwhelming, but it is also a rewarding process and can streamline and shorten the review process going forward.

Over the last 15 years, the collection review process has led to collaborative relationships between each community and the IARC staff. This collaborative process is not viewed as a NAGPRA consultation, but these conversations help inform approaches to culturally appropriate care, which vary among communities, and guide policy development. Items are occasionally identified as culturally sensitive that were previously unknown to staff and are then restricted from future research and access. In addition, smoother pathways for incoming research requests have been developed. The process that grew from the initial collections review with the Pueblo of Zuni has shaped the policies and procedures of the IARC, especially those related to research access.

Case Study 3

The Gilcrease Museum has been actively working to increase accessibility to collections through a public online database. In 2017, Gilcrease was awarded an Institute of Museums and Library Science (IMLS) grant to support the cataloging, imaging, and digital publication of more than a thousand Native cultural materials related to Native Nations now based in Oklahoma. Unfortunately, neither a plan nor funding for consultation was included in this project. Subsequently in 2018, Gilcrease received a NAGPRA Consultation & Documentation grant to conduct collections reviews and consultation with 15 Native Nations whose cultural material was included in the digitization project. These consultations were often challenging at first, because many Native Nations were upset that they had not been included from the outset and that some items had already been accessed and imaged. Because consultation had not been the first step, some of the previously completed imaging and cataloging work needed to be restricted or destroyed. The digitization grant had to be amended to decrease the number of items that would become available online. Gilcrease prioritized its relationships, communicated transparently, and expediently followed through with the changes, requests, and protocols shared by representatives. Those conversations yielded meaningful guidance on access and imaging protocols and led to several repatriations.

As a direct result of this experience, Gilcrease now requires approval from affiliated Native Nations(s) before taking new images or sharing images of their cultural material on the public database. Image requests now follow a parallel process to collections access requests and typically require a letter of support from the affiliated Native Nation(s). This standard goes beyond Duty of Care, which does not offer protection for images or associated documentation and only applies to NAGPRA-eligible material. However, many Native Nations view images of sensitive items as requiring similar restrictions as physical items.

Although the IMLS grant project’s actions and priorities should have been developed with the affiliated Native Nations, the NAGPRA consultations and collections reviews still shaped the project’s final form and fundamentally changed the operations and priorities of the Gilcrease Museum. These conversations initiated long-lasting and mutual relationships that have led to repatriations and the collaborative development of exhibitions and other digitization projects. Involving designated representatives of Native Nations in the early design and planning of subsequent projects has created more meaningful content, maintained deeper and more reciprocal relationships, and saved money and time.

Tips on How to Change Your Institution’s Research Policy

As shown in these case studies, institutions need to determine their priorities and goals when developing policies and procedures that support ethical research while aligning with new Duty of Care provisions (Table 1). There can be no universal standard template for all institutions because the resources, capacity, collections, and relationships of each institution are unique. Instead, consider these three core concepts when developing the framework of institutional policies and procedures:

1. Determine what the institution can commit to and is willing to implement.

2. Understand the institutional goals for research on collections.

3. Outline accountability to the policies and standards.

Policies establish boundaries around what an institution is willing and able to enact: they are tools to reinforce the foundation, mission, and goals of institutions (School for Advanced Research 2023). Although institutions should avoid overpromising and underdelivering, they should also reflect on their priorities and possible resource reallocations (Edginton Reference Edginton2024).

Once institutional priorities and a policy framework are aligned, invite designated and official representatives of Native Nations to the development process. Let those conversations and recommendations lead policymaking decisions, as discussed in the first case study. To determine who to invite to participate, look first to the tribes most represented in the collection and to those in physical proximity to the institution. Include funds or resources in the budget to compensate Native representatives for their time.

Discuss potential real-life scenarios to help shape the policy and procedures to fit the Native Nations’ capacities and preferences. Compliance with NAGPRA and its regulations, including the Duty of Care provision, must be a component of an institution’s policy. The next logical step is to require letters of support to use or research sensitive collections, associated documentation and images, or even all Indigenous cultural materials (Indigenous Collections Care Working Group 2024).

Consult with Native Nations to determine how consent is documented and how they would like to communicate about research requests, as shown in the second case study. Some Native Nations may prefer the institution to liaise between them and the researcher, at least at first, whereas others may prefer that the researcher make initial direct contact. Relationships and trust make everything run smoother. Maintaining consistency and transparency in all communications and staying connected will ensure a smooth implementation for all involved.

Uploading records, information, and images to a public online database can help encourage research and reduce inequities of access. However, when not implemented in consultation, this can also mean that images of and information related to NAGPRA cultural items and other culturally sensitive materials are publicly accessible and therefore could be used in inappropriate ways, as learned in the third case study. Consider how your institution will approach internal and external access to images and catalog records.

Policies should also clearly lay out the process for the review and approval of requests. This could include establishing a committee composed of internal and external stakeholders, or a structured multilayer internal review process could be developed (Shannon Reference Shannon2007). An intentionally balanced oversight committee can hold both the institution and the researcher accountable to institutional policies and standards.

Native Nations want their perspectives, expertise, and cultural protocols to be respected and incorporated in the research of their cultural materials. This perspective has been repeatedly and consistently expressed to us throughout our careers, as well as during the creation of the Indigenous Collections Care Guide. We have also consistently heard that many Nations do not have the capacity to review, respond to, or be involved in research proposals or requests. In addition, although researchers and museum staff want to respect the perspectives, expertise, and cultural protocols of Native Nations, too many other urgent priorities demand staff time. The Duty of Care provision is forcing the reallocation of resources and creating internal pathways for decision-making for both Native Nations and institutions. Vetting and responding to research and access inquiries may be new experiences for Native Nations. Developing and learning these pathways will take time, as will shifting standard research practices, but mutually beneficial and well-rounded research will grow from scholars and institutions reaching out to and involving Native Nations.

Even with established procedures, meaningful collaborations require investments of both time and finances. Allocating that time and funds for consultation contributes to relationship building and supports ethical research methodologies. Remember to value and recognize the expertise of Native consultants and partners.

Researcher Engagement and Methodologies

As the case studies illustrate, institutional policies around research and access dictate the interactions between researchers and the collection. Policy statements inform resource allocation, ensure that practices continue beyond individual employees, and hold the institution accountable to all constituents. Collections access and research policies can establish ethical practices that elevate the protocols and priorities of descendant peoples and Native Nations.

With these changes, institutions must clearly communicate expectations to researchers regarding the timeline, consent requirements, and behavior and protocols when interacting with collections. Most institutions already have standardized access and research request forms, and these expectations can be integrated into those established procedures. Alternatively, these processes can be posted on an institution’s website. Institutions should have researchers formally acknowledge them, just as they do other expectations related to a research visit.

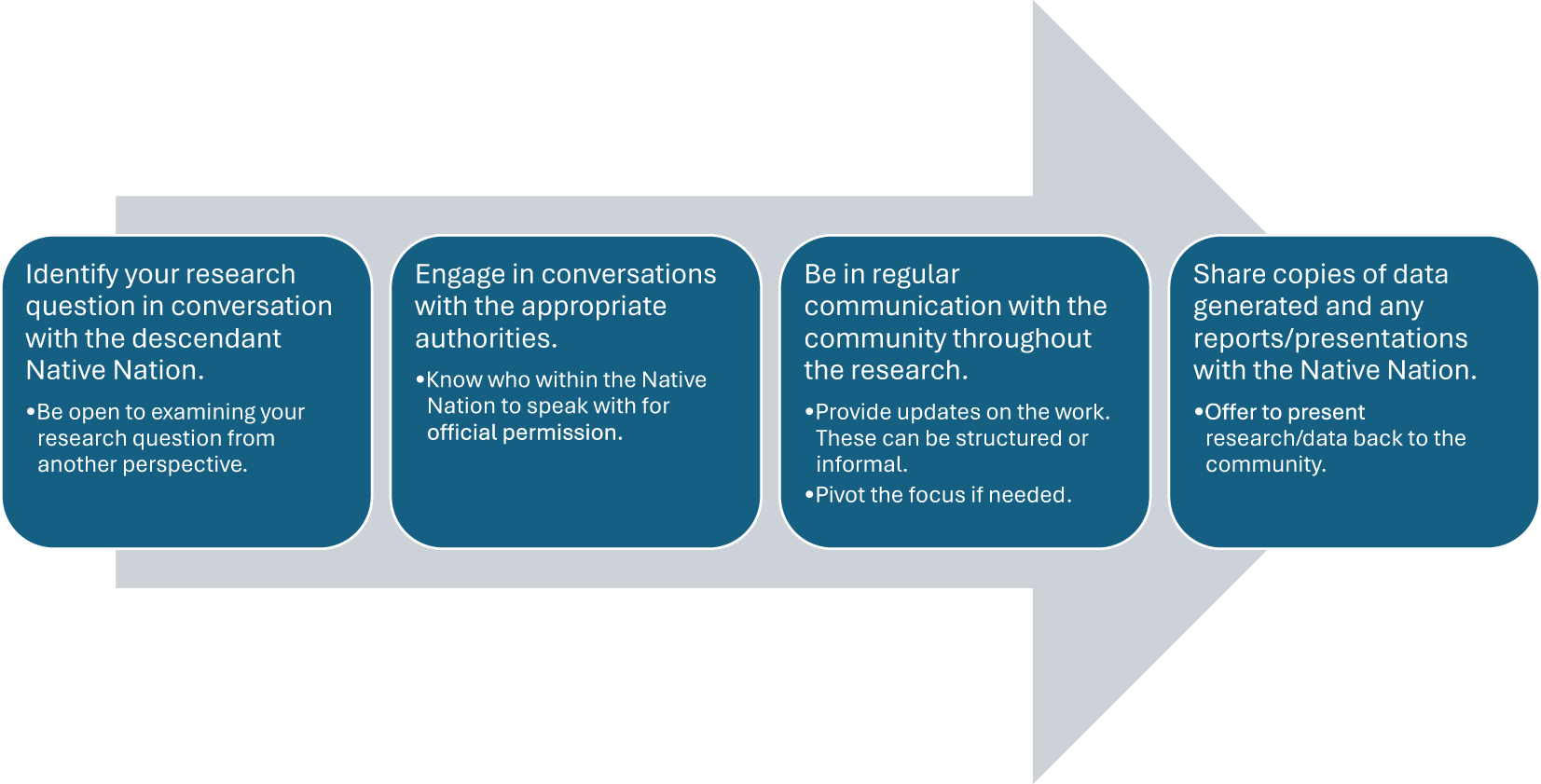

The responsibility to develop policies and guidelines around research access is not solely that of the institutions. Archaeologists and researchers can and should take on some of the responsibility to shift their own approaches, as shown in Figure 2. Researchers are often aware of the context and potentially sensitive nature of the subject matter and items related to their research questions. They should therefore reach out and consult with relevant Native Nations to not only request consent as required by the Duty of Care clause (43 CFR §10.1(d)(3)) but also to develop research goals. It can damage relationships and be offensive for a Native Nation to learn of research conducted on their cultural materials by attending a conference or receiving an advertisement for a lecture. Instead, a few meaningful changes in the research approach will pay dividends for the researcher, Native Nation, academic institutions, and field of archaeology as a whole.

Figure 2. Steps that researchers and students can take themselves.

The next generation of students and archaeologists should be trained to recenter their research approach and methodology on collaboration with Native Nations, which often want to be involved in research on their past cultural materials. When developing thesis projects or dissertation research, engage in open conversations with tribal representatives to determine a research question or topic that you both want to learn about, as suggested in Figure 2. Active collaboration will result in stronger relationships and comprehensive research.

Conclusion

Implementing policies and methodologies like those described in this article will require more from institutions, Native Nations, and researchers. Additional time and resources are needed to develop relationships and identify communication pathways. However, this should not be seen as a burden or a deterrent. In fact, we have learned that many Native Nations have a list of research projects and ideas awaiting eager scholars that would enrich understanding of cultural affiliation and intertribal relationships and their cultural revitalization efforts. Partnering and collaborating with communities to conduct research strengthens projects and increases funding opportunities and mutual learning.

Ethical and reciprocal research is essential for establishing respect and overall well-being in building these equitable relationships. When conducting research, researchers need to remember that these are not just collections: they are relatives, personal belongings, and connections to people here today (Shannon Reference Shannon2019:5). This approach is becoming best practice within the museum field and will eventually become the academic standard (Krupa and Grimm Reference Krupa and Grimm2021; Marsh Reference Marsh2023; Roberts Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Thompson, Garland, Butler, deBeaubien, Miranda and Hunt2023; Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Arsenault and Taylor2022). Policy change can be challenging and time-consuming. However, the reward is worth the investment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the previous and current members of the Indigenous Collections Care Working Group for their insights and perspectives on ethical research. We also appreciate the participants in review sessions for the Indigenous Collections Care Guide who shared their experiences with researchers and their desire for ethical research. We would also like to thank Cynthia Chavez Lamar, the Pueblo of Zuni, and the cultural advisers who assisted with the initial IARC collection review, Jim Enote and Octavius Seowtewa. A thank you also to Donald Slater for providing Spanish-translation services. In addition, we would like to acknowledge the support of each of our institutions and colleagues in our work and in ethical research practices. This article developed from the session “In Search of Solutions: Exploring Pathways to Repatriation for NAGPRA Practitioners” (NAGPRA Day at the SAA) at the Society for American Archaeology’s 89th Annual Meeting in New Orleans. No permits were required for this work.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Science under Grant MG-252895-OMS-23.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were used in this article.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.