THE HISTORY OF TIKTOK

TikTok gained popularity in 2020 amid the global pandemic, but its history goes back through multiple app iterations. ByteDance, the parent company of TikTok, was founded by Zhang Yiming in 2012, and it launched the app Douyin in China in 2016 to allow people to create and post short video clips of themselves. Around the same time, Mucial.ly was another Chinese-origin app that used the same concept but focused specifically on lip-syncing and dancing. Whereas Douyin was popular in China, Musical.ly dominated the market in the United States and became the top app on iTunes in 2015. However, ByteDance developed an algorithm that responded to user preferences reflected in the types of videos a user created, liked, shared, commented on, or marked “not interested in,” and the accounts they followed. Musical.ly lacked this feature and was eventually purchased by ByteDance, which subsequently merged Douyin and Musical.ly into the rebranded global app TikTok in 2018 (Routh Reference Routh2021).

The creative purpose of TikTok is to showcase short videos shot on a user's phone and to allow people to post their content in a phone's full-screen format. The FYP (see Figure 1) continuously shows TikToks (the name used to refer to videos on the app) that are personalized to the user's interests based on prior interactions with the platform. Today, TikTok is a media giant similar to Instagram and YouTube. The popularity TikTok gained resulted in other social media apps incorporating short video options into their platforms, known as Reels on Instagram and YouTube Shorts on YouTube (Schneider Reference Schneider2021). Differences remain among the various social media platforms. For example, a YouTube video usually requires more resources to create, such as professional video camera equipment, lighting, microphones, and sets; otherwise, the low quality of phone-produced videos may be less appealing to viewers. Instagram focuses on aesthetics, which may not be achievable through a basic phone camera. Furthermore, its tradition is rooted in still photographs rather than videos. A TikTok can be recorded by a phone, which makes the app popular and accessible to many people who do not find the other two platforms to their liking. User age might once have affected the decision to use TikTok compared to Instagram or YouTube—in pre-pandemic times it was more popular among teenagers (Generation Z). We appear to be reaching a point where all the apps are used by multiple generations, but each app has a different niche. Given the global ubiquity of smartphones, the accessibility of the TikTok app allows a user to not only record more raw and unfiltered videos but also view stories from around the world. Although not the primary goal of the app, there is an opportunity to use TikTok to diversify our understanding of each other's cultures (Routh Reference Routh2021).

Figure 1. The For You page can be found on TikTok at the top of the phone screen.

TIKTOK: ARCHAEOLOGY EDITION

Here, I dig deeper into TikTok's archaeology-based videos. To demonstrate what a user who wants to learn more about archaeology would see, I typed “archaeology” into the search engine on TikTok. The results will, of course, be tailored to my prior viewing habits based on the algorithm. However, before this experiment, I had never searched specifically for archaeological content. I watched the first 30 videos that appeared in my feed, not selecting videos based on interest, length, or posted location. In Excel, I recorded three key points: (1) the creator, topic, and purpose; (2) observations about the comments sections of each video to understand the engagement process among users; and (3) an inventory of whether each video focused on an artifact, a structure, an artistic piece, human remains, a history lesson, a person such as an archaeologist, or miscellaneous (Table 1). Some creators posted multiple videos about archaeology.

Table 1. The First Two Rows of My Excel Spreadsheet Documenting TikTok Videos about Archaeology.

Summary of Observations

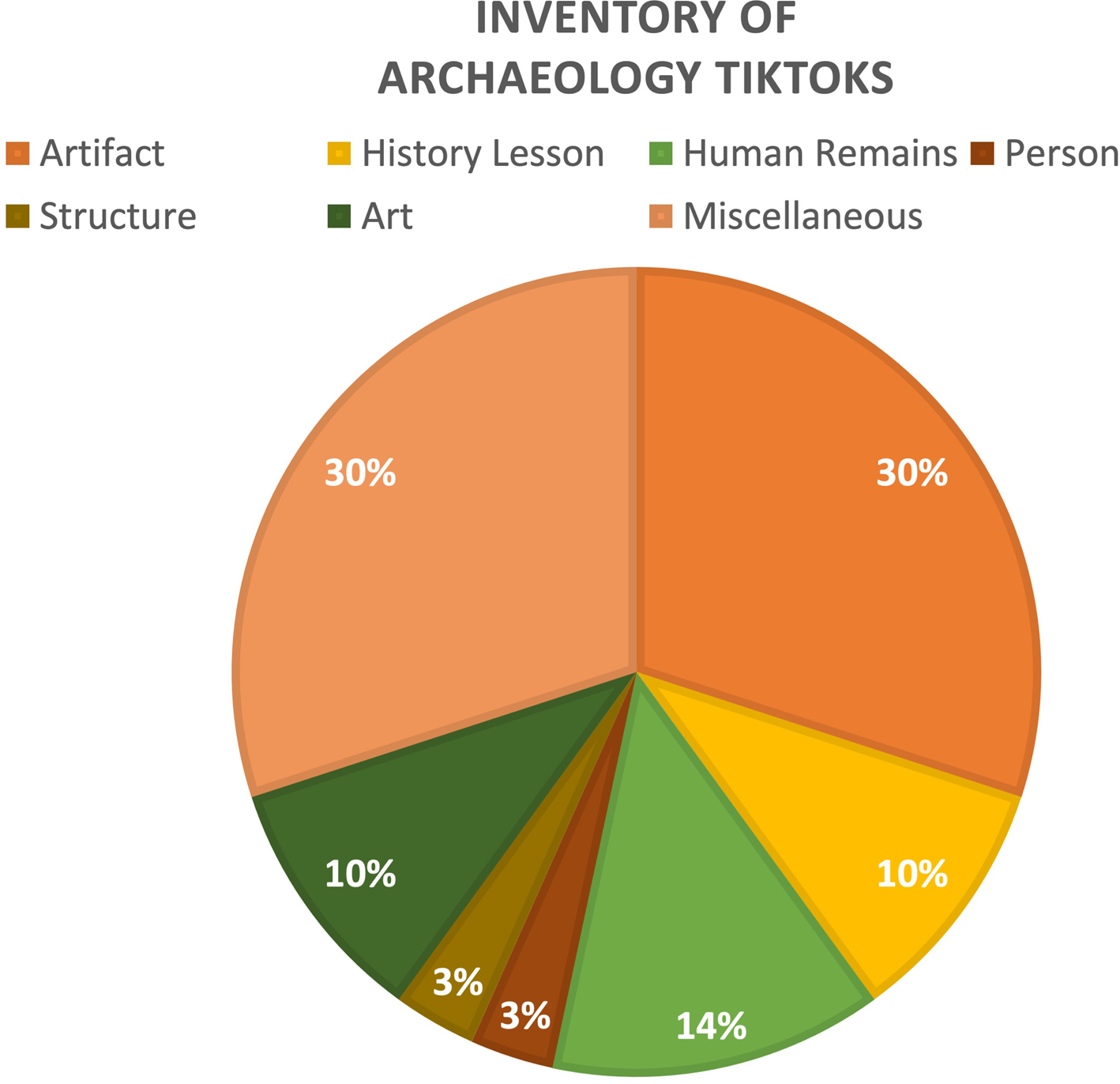

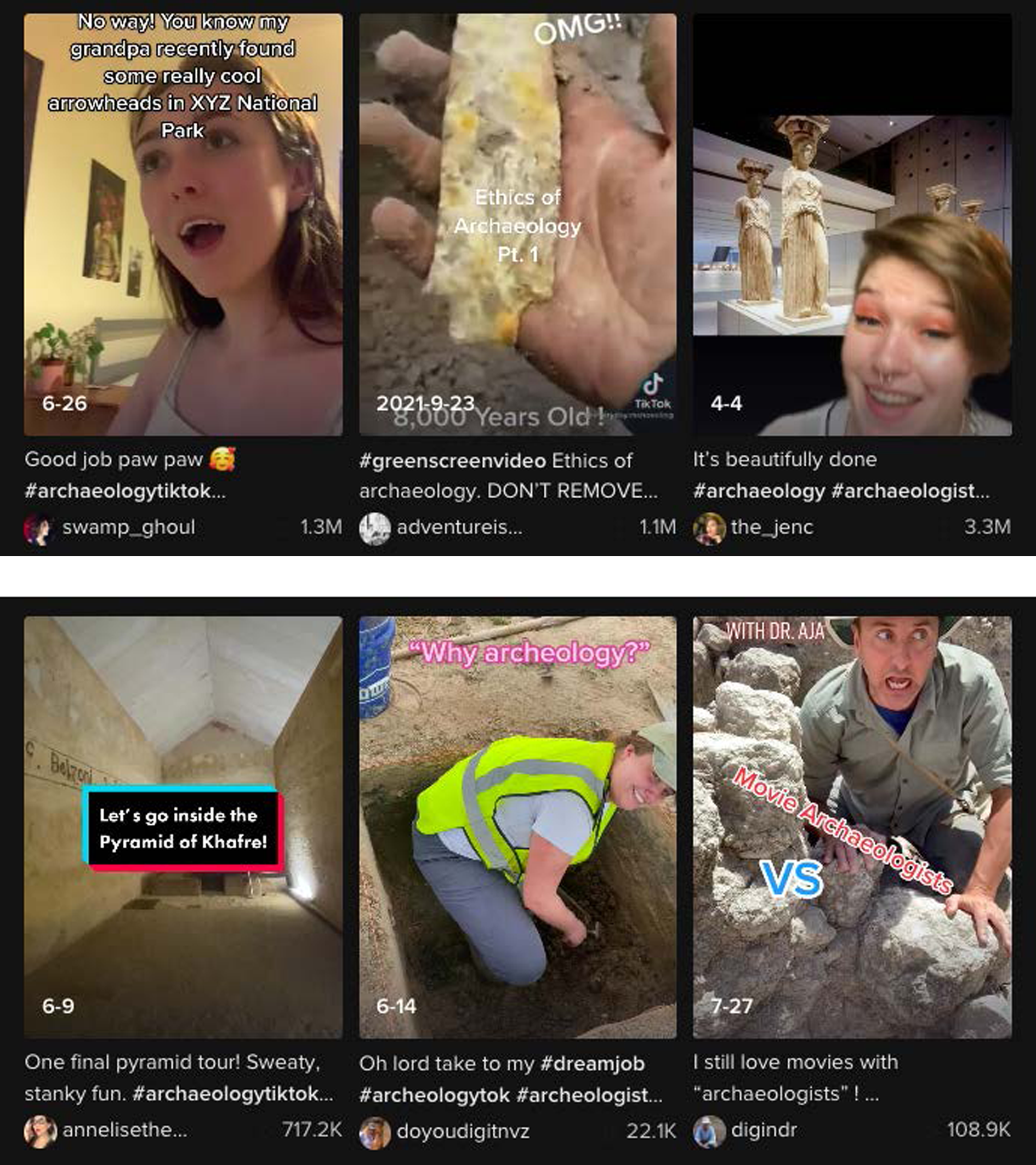

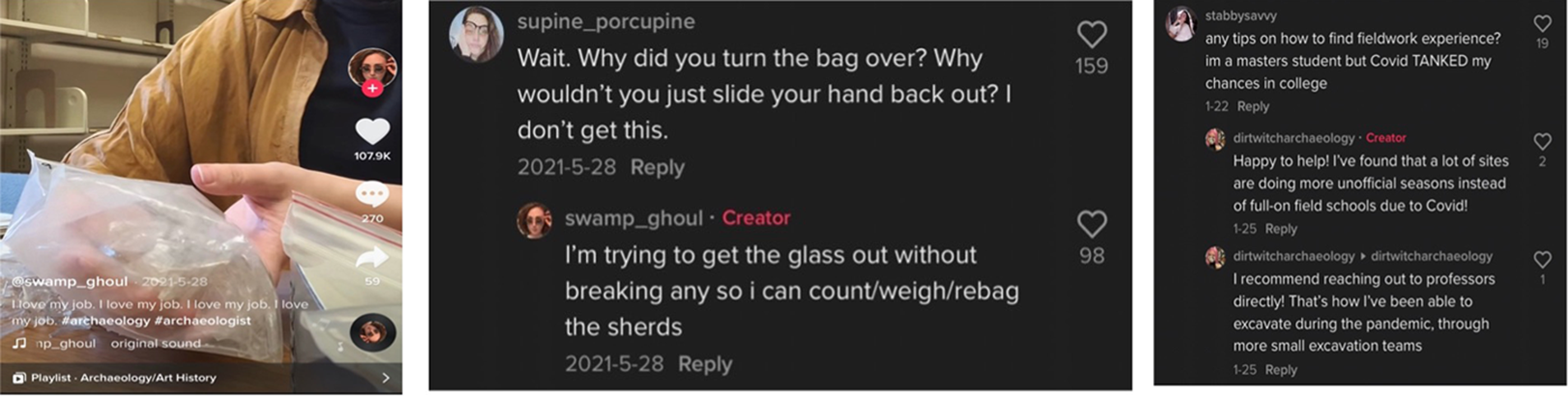

Of the 30 TikToks I viewed, the majority of the video clips were both informational and engaging, especially the ones debunking myths in archaeology. It came as a pleasant surprise that several of the videos were not solely focused on prestigious artifacts that are often the public's perception of archaeology. Figure 2 depicts a chart of inventory categories for the 30 viewed TikToks. Instead, many videos emphasize past inequities, showing places and objects used in everyday life and how they differ from the objects usually seen in museums. The archaeologists on TikTok were also keen to show what they do for a living. One archaeologist recorded herself removing broken sherds of glass from a bag while trying to preserve what was left for counting, weighing, and re-bagging. In another video, an archaeology student created a slideshow of photos from her fieldwork, highlighting the reality of fieldwork, which greatly contrasts with the archaeological field experiences portrayed in popular media—such as in the Indiana Jones films. Both of these creators had commenters who expressed interest in becoming archaeologists and inquired about the process to become one. The creators were friendly and responded to the eager prospective students in archaeology. I highlight these two examples specifically because they are not typical of the glamorized versions of archaeology where we see only pyramids, temples, and rare objects. TikToks like these not only depict the reality of what archaeologists do today but also introduce facts about daily life in the past. Presenting information as TikToks can help spread knowledge to a much wider audience about wealth inequities and diminish stereotypes about the grand lifestyles in places where a moderate or even lower quality of life existed in the past.

Figure 2. Chart depicting inventory categories for the 30 viewed TikToks.

Sometimes, excavation videos sparked indignance toward archaeologists working in the field, with comments demanding that they “give it back to the community.” This sparked a debate in the comments section on what an archaeologist's job is, and why it is important. Approximately one-third of the videos I watched generated an engaging comments section, in which people debated the ethics of excavation. Other types of TikToks focused on debunking myths (e.g., aliens did not build the pyramids or other grand structures). Overall, each video had a large audience that appeared curious about what was occurring or about what the goals of the work were.

It can sometimes be challenging to identify a person's background on social media given that not all creators add details to their bios; it is their choice whether they publicize their profession or not. Some creators were professionals in the field, but many were students interested in joining the field. The individuals outside of these two categories were not necessarily less captivated but had more of a “that's cool” reaction, and many times asked clarifying questions such as why glass sherds were being removed from a bag in the way they were (see Figure 3). Overall, TikTok's goal of putting things one cares about or is generally interested in on one's FYP works well for those interested in archaeology. It reaches a wide spectrum of users, and things that do not capture one's attention pop up less frequently or might stop altogether. The algorithm makes recommendations based on one's prior liking, sharing, or commenting on videos. However, all TikToks are accessible because they are searchable and viewable by everyone.

Figure 3. Screenshots from searching “archaeology” on TikTok.

IMPACTS

TikTok and Education

In a 2016 article, Cynthia Brame made various suggestions for the proper pedagogical deployment of video content. She writes, “The first and most important guideline for maximizing student attention to educational video is to keep it short” (Brame Reference Brame2016:4). In her study, students watched entire videos, but as each video progressed, engagement and retention decreased. She observed that the average engagement time for videos shorter than six minutes was close to 100%, indicating maximum engagement until that point. Students tended to get distracted as each video stretched on above this, decreasing the retention of informational material (Brame Reference Brame2016:4). TikTok supports short videos, so it allows educators to structure their lessons and incorporate the platform in a way that allows students to learn something new in 10 minutes or less. Given that it is the currently trending platform among students, now is the time for educators to deploy this tool. With teaching modes fluctuating back and forth from online to in person, it is vital to study how students engage with new material and retain information. TikTok also engages students in interactive conversations through comment threads. Just because students’ attention spans are held for six minutes or less does not mean longer videos should be eliminated. The goal here is to focus on making the content of informational videos high quality. Should an archaeological topic require more than six minutes, it may still be more beneficial to break it up into multiple short videos. This allows students to refocus before beginning the next part, and ultimately it would relay content that is being processed and stored in memory.

A Google search for “learning through TikTok” finds several articles discussing whom the platform benefits and how (Kahil and Alobidyeen Reference Kahil and Alobidyeen2021; Saidi Reference Saidi and Hussein2021). The majority of the articles are written for teachers, who hold the power to influence the techniques future students will use to learn. Traditional teaching and learning methods were already increasingly incorporating digital and online teaching, even before the acceleration caused by the pandemic (Cobb et al. Reference Cobb, Rogers, Ford, Blasdel and Renninger2019). Fully moving to online learning shifted the way teachers interacted with their students. TikTok allows students to learn and collaborate creatively (e.g., making an informational TikTok for a history group project). It potentially makes learning more fun, and with the future of education being social and digital, it gives teachers and students a space to teach and learn (Faktor Reference Faktor2021). TikTok can serve as a place to introduce a student to a topic. Given the short format, educators will be most effective when the information is highly focused, with the understanding that additional information is available outside of TikTok. TikToks can be one tool in an educational resource package; students can then expand to other resources (articles, books, and other valid sources of information) to learn more if they so wish. In addition to the intended student audience, anyone in the public would have access to the videos as well, which could further ignite learning about the topics.

As easy as it is to focus on the positive features of using social media, some aspects should be approached with a critical eye. Emmitt (Reference Emmitt2022) discusses how YouTube videos add to the spread of misinformation, “with pseudoarcheology given a platform that is mixed with factual content” (Emmitt Reference Emmitt2022:5). Out of the 30 TikToks I watched, I flagged 10 of them as questionable because either they violated certain ethics (e.g., improper excavations as compared to the care with which professionals work [Petrosyan et al. Reference Petrosyan, Azizbekyan, Gasparyan, Dan, Bobokhyan and Amiryan2021]) or creators appeared to be spreading misinformation. Although generating excitement and drawing attention to the significance of archaeology is important, it should be done in a way that removes false perceptions about the ancient world. Users of TikTok are susceptible to watching clips that misinform. Figure 4 shows screenshots of TikToks found on archaeology and portrays how easy it is to come across this information, which is why we have to be extra careful as well with what information we choose to absorb. Students should be cautioned by educators about this possibility and guided on how to navigate information properly. Questioning resources and fact-checking could be skills developed through this process—one part of the multifaceted skill set we call “digital literacy” (Kansa and Kansa Reference Kansa and Kansa2021).

Figure 4. Screenshots from TikTok: (l eft) archaeologist removing glass sherds from a bag; (center) a creator responding to a question about why she is removing these sherds; (right) an archaeology PhD student sharing tips on how to find fieldwork experiences.

Museums Using TikTok

Because TikTok can reach a wide audience interested in the fields of archaeology, history, art, and cultural heritage, some museums have experimented with the platform for public outreach. The Akron Art Museum's TikTok account offers a combination of duet videos, art history breakdowns, and museum tours. The museum also has a series called Why Is That Art, explaining “the historic and artistic significance of works in the institution's contemporary art collection” (Lu Reference Lu2022). The deputy director and CEO of the Akron Art Museum, Seema Rao, shares, “Audiences who didn't know they could like museums are now on TikTok. . . . TikTok is sharing so much knowledge, even if the cadence is very different from traditional education. As a field, we'd be silly not to connect there” (Lu Reference Lu2022). She explains how Instagram users usually visit the museum's account because they like art, but TikTok works differently. The museum's TikTok audience is at a national level, and users are looking for fun, quick, and sometimes humorous videos to watch. This draws in an audience for which in-person museum visits, longer YouTube videos, or photos shared on Instagram may be less accessible or engaging. They can learn snippets of information about art, history, or other topics while they scroll through the app.

CONCLUSION

From the exploratory analysis conducted for this review, I observe that archaeology TikToks attract viewers. Given their interest, it would be beneficial to pull artifacts from various social and economic classes to display in the TikToks, highlighting aspects of everyday life of the past and elucidating important understandings, such as the inequities that are often overshadowed in the public's perception of the past. Learning through TikTok has proven to be a point of discussion and an engaging teaching method. Because of this, knowledgeable creators (e.g., archaeologists, students of archaeology, professors, etc.) can try to put forth information in their TikToks (or other social media accounts) that showcase the work done by archaeologists to study ancient inequality or other archaeological topics with modern relevance. As Rao pointed out (Lu Reference Lu2022), the videos can be made fun and quirky to gain viewership and ultimately educate a wider audience.

Emmitt (Reference Emmitt2022) raises the concern of having amateurs make videos about archaeology. This will be difficult to regulate. A proposed solution to this is “debunking” the myths or inaccuracies that derive from pseudoarchaeology. TikTok creators can engage in a dialogue called a “duet,” in which they react to each other's videos. This process could be used to respond to the claims made by amateurs. These duets generally keep with the clever, fun, and humorous atmosphere of TikTok, which encourages scrolling on the app, potentially increasing engagement. However, creators that responded in a serious tone and stringently reprimanded other amateur archaeology creators rubbed the audience the wrong way. The creators who lightheartedly poked fun at the amateurs were more well received by the viewers. TikTok is a great platform for visual learners. It is flexible and offers a relaxed way to learn that meets the contemporary attention span. Online learning is an integral aspect of modern education, adding engaging and relatable content that could further students’ education and retention.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Amy Thompson for inviting me to write a digital review as part of her course at the University of Texas, Austin.