Contextual rating of social adversity has its origins in the work of George Brown and colleagues (Reference Brown and HarrisBrown & Harris, 1978). This review evaluates its strengths and weaknesses in rating the effects of social adversity on depressive disorder. We write from the perspective of its usefulness for clinical and training purposes both to the consultant psychiatrist and to the community mental health team working in general adult psychiatry.

What is contextual rating of social adversity?

Social adversity and social factors that mitigate it can be validly measured with or without considering their likely interpretation (context) by the individual. Contextual rating of social adversity is often clinically meaningful for both the health professional and the patient, enabling them to understand how, when and why social adversity may be connected with the patient's depressive disorder. In research, associations between social adversity and depression are also stronger using the contextual rating method than other methods (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997). The main alternative approach is to consider that each life event has a similar adverse effect on each individual. In this method, life events are sometimes ranked in terms of the likelihood of causing an adverse emotional effect in an individual.

The nature of contextual rating is best illustrated by an example. A life event such as unemployment may be more of a blow to a 40-year-old man who is already in debt, has a large family and has worked all his life in one specialised field than to another 40-year-old man without such debt or commitments and who has a wide range of experience and skills. The former is likely to experience unemployment as a severe threat to his well-being, whereas the latter may even consider it as a fresh opportunity. A problem with contextual rating is that great care has to be taken to avoid making inaccurate assumptions about mitigating circumstances and causality. For example, it is possible that the reason our 40-year-old man is depressed, unemployed and in debt is because he is a heavy consumer of alcohol, which independently contributes to his depression, unemployment (e.g. through bad time-keeping) and indebtedness.

Brown's model of social adversity

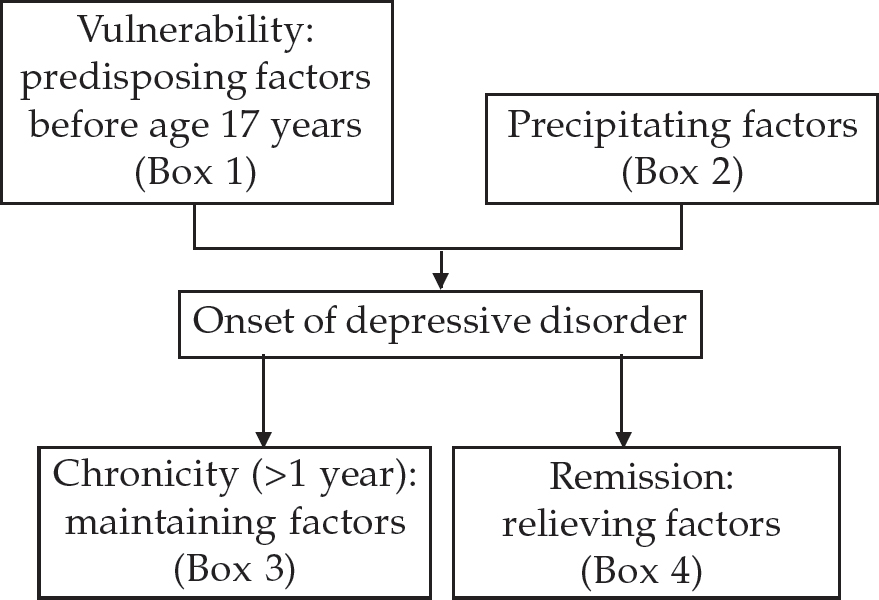

Figure 1 illustrates the psychosocial formulation of a patient with a non-psychotic depressive episode. The model uses traditional categories of predisposing or vulnerability factors (Box 1), precipitating factors (Box 2) and maintaining factors (Box 3) likely to cause chronicity for 12 months or more. Vulnerability factors may increase the likelihood of both precipitating interpersonal life events and difficulties, and maintaining factors (Reference Brown and MoranBrown & Moran, 1994). Unlike traditional formulations, there is a systematic exploration of the patient's assets, existing resources and potential resources that might be used to achieve recovery: these are the relieving factors (Box 4).

Fig. 1 Formulation of psychosocial problems in patients with non-psychotic depressive disorder

Box 1 Vulnerability (predisposing) factors for depressive disorder occurring before age 17 years (from Brown & Moran, 1994)

Sexual abuse. Physical sexual contact, excluding willing contact with non-related peers in teenage years

Parental indifference. Physical or emotional neglect: parental lack of interest or involvement in material care, school work, friends and so on

Physical abuse. Violence shown towards the subject by a household member: actual beatings, threats with knives and so on

Loss of a parent. Death or separation followed by inadequate parental care

Box 2 Precipitating factors for the onset of depressive episodes (based on Brown & Harris, 1978; Brown et al, 1988 Brown et al, 1995)

Severe, acute life event. Acute life situation of recent onset that carries or potentially carries a serious long-term threat to the emotional well-being of the individual. Losses can be interpersonal, material or loss of a cherished idea (e.g. finding out about a child's delinquency)

Chronic life difficulty. Life situation lasting at least 4 weeks that carries or potentially carries a long-term threat to the individual's emotional well-being

Poor-quality social support. Particularly important at a time of crisis or in the domain of the life event or life difficulty. It may itself be a provoking life event or life difficulty; sometimes the anticipated buffering effect against a life event is not experienced

Box 3 Maintaining factors for depressive episodes (from Brown & Moran, 1994; Ronalds et al, 1997; Harris et al, 1999a,b)

Further negative life events

Persistent poor quality social support

Poor coping style:

-

• self-blame and helplessness

-

• denial of problems

-

• inability to solve problems

-

• blaming others or external forces

Inability to obtain adequate social support:

-

• fear of intimacy

-

• denial of need for intimacy

-

• enmeshed intimate relationship

Low educational level

Box 4. Relieving factors for depressive episodes (from Brown et al, 1992; Leenstra et al, 1995; Harris et al, 1999a,b)

Life events (not mutually exclusive)

Fresh start: new role, positive change, reduces severity of difficulties or deprivation (e.g. housewife starts part-time job once children at school)

Potential fresh start: positive change, reduces severity of difficulties or deprivation (e.g. start of a relationship but no clear change of role yet)

De-logjamming: reduces severity of difficulties (e.g. separation from violent husband, but some postal contact to resolve financial issues)

Anchoring: role change and increased security (e.g. marriage after dating)

Difficulty reduction

Difficulty neutralisation: ending a difficulty (e.g. divorce, so no need for any contact with violent husband)

Goal attainment: realisation of important goals

Improved quality and consistency of support

Existing core supports

Supports become core

New support

Social adversity has a number of properties whose meaning needs to be considered from the patient's perspective. These include the amount of loss, amount of threat, whether the effects on the person's life are wide-ranging or long-lasting, consequences and controllability (by the patient alone or with the help of others). Their meaning must be understood in the light of the patient's past experiences and current social context (Box 5). Brown's group has shown that life events and life difficulties are significantly associated with the onset of depressive episodes only if they are severe and carry long-term potential for detrimental effects on the patient or his or her close relationships (Brown et al, 1988). Social adversity is more likely to have an adverse effect if the patient perceives that it affects more than one life domain (e.g. both home and work) and it is not under the individual's control.

Box 5 Domains of a person's life that may be affected by social adversity

Interpersonal relationships (e.g. marriage, close ties with family or friends)

Housing and neighbourhood

Finances

Work

Education

Social or leisure activities

Legal or police problems

Health, sickness and disability

More distant family, previous friendships

More recently, Brown's group has claimed that severe life events with the meaning of humiliation to the subject, and severe life difficulties with the meaning of humiliation or entrapment to the subject, are predictive of depressive episodes. Losses or threats, other than loss of a close other, that do not carry these meanings are not predictive of depressive episodes (Brown et al, 1995). Hence, the subject tends to associate individual redundancy with feelings of shame and the meaning of humiliation, failure and rejection, whereas mass redundancy owing to closure of the whole firm carries no individual shame (Reference Harris and BrownHarris & Brown, 1996). Life events or difficulties involving the meaning of humiliation tend to be divided into other people's delinquency that devalue the subject (e.g. having a child charged with burglary), or a snub or rejection (e.g. a marital partner or child repeatedly expressing the wish to leave home because of the subject). A life difficulty with the meaning of entrapment is likely to have lasted for at least 6 months, and in the patient's view there will be no realistic chance of improvement (e.g. looking after a dependent close relative). The patient's view of entrapment does not necessarily mean that the situation cannot be helped by a clinician.

Evidence base for clinical use of contextual rating of social adversity

Prospective naturalistic research

Most of the theoretical underpinning of the contextual life-events research described above was ascertained from two separate large, prospective, longitudinal studies of non-clinical samples of working-class women living in London (Reference Brown and HarrisBrown & Harris, 1978; Reference Brown, Adler and BifulcoBrown et al, 1988). To be relevant to the work of mental health professionals, the findings of these studies must be confirmed in clinical samples of both genders studied in general practice, out-patient and in-patient psychiatric settings.

In a 6-month outcome study at a single Manchester general practice, improvement in depressive disorder was associated with relief of chronic social difficulties, especially in close interpersonal relationships, work and housing (Reference Ronalds, Creed and StoneRonalds et al, 1997). These positive life events either neutralised a previous severe life event or reduced the threat to emotional health from a chronic life difficulty. In a large Dutch study of 170 primary care patients with depressive and/or anxiety disorder followed for 3Þ years, positive life changes (fresh-start or anchoring life events, goal attainment, difficulty reduction) facilitated recovery (Reference Leenstra, Ormel and GielLeenstra et al, 1995). However, positive life events were neither necessary nor sufficient for recovery.

In female psychiatric out-patients, childhood adversity and current interpersonal difficulties predicted chronicity of depressive disorder, while good-quality emotional social support reduced the risk of chronic depression (Reference Brown, Harris and HepworthBrown et al, 1994). Similar results were found in an American out-patient sample of women and men (Reference Zlotnick, Shea and PilkonisZlotnick et al, 1996). In male and female psychiatric out-patients, life events and life difficulties in the previous 6 months were independently associated with failure to recover from first-onset and second episodes of non-psychotic depressive disorder (Reference Brugha, Bebbington and StretchBrugha et al, 1997). Better social support predicted recovery from all but first episodes of depressive disorder.

Studies of in-patients treated for depressive episodes (e.g. Paykel et al, 1996) and of out-patients with melancholic or psychotic subtypes of depressive episode (Reference Harris and BrownHarris & Brown, 1996; Reference Brugha, Bebbington and StretchBrugha et al, 1997) have generally failed to demonstrate that outcome is associated with the threat from current life events or chronic life difficulties, the creation of fresh-start events or improved social support. Post et al (1986) noted that life events often precipitate early episodes of depression, but as the number of episodes increases Òthe illness appears to evolve its own rhythmicity and spontaneity, independent of life events”. This behavioural sensitisation may explain why social adversity has little effect on outcome in patients with depression who have had out-patient (Reference Brugha, Bebbington and StretchBrugha et al, 1997) or in-patient (Reference Paykel, Cooper and RamanaPaykel et al, 1996) treatment for more than two previous episodes. On the other hand, Johnson et al (1998) report that positive life events that are internally, consistently and globally attributed by patients to their own efforts reduced hopelessness and depression in in-patients with recurrent depressive disorder.

Randomised controlled treatment trials

These explore whether interventions using contextual rating of social adversity can promote recovery from depressive episodes. Harris et al (1999a, b) showed that befriending by female volunteers to improve emotional support promoted remission compared to no treatment in a non-clinical sample of women with depressive episodes lasting more than 12 months. The offer of befriending was as important as the reality of befriending in promoting remission. These subjects had not sought help for their depression, and befriending might not be as effective in a clinical sample of patients who had already decided to do so. Fresh-start life events, the absence of additional negative life events, the ability to make supportive interpersonal life events (standard attachment) and befriending all independently promoted remission. Standard attachment enabled fresh-start events to happen.

Corney (1987) demonstrated that casework, through enhanced practical and emotional support, relieved the symptoms of depressive episodes of women with marital difficulties compared to treatment as usual by the general practitioner (GP). Marital therapy aimed at enhancing the development of a close confiding relationship significantly reduced the symptoms of depressive disorder in women attending psychiatric out-patient clinics (e.g. Waring, 1994). An intervention that successfully increased the finding of full-time work for the long-term unemployed also significantly reduced the prevalence of psychiatric disorder (Reference Proudfoot, Guest and CarsonProudfoot et al, 1997). However, in some of these interventions, it is not clear how much of the benefit of the intervention was due to improved social support, fresh-start events or reduction of threat from life difficulties, and how much was due to therapeutic ingredients uncharacteristic of the contextual approach, for example, the promotion of intimacy in marital therapy.

Psychiatric comorbidity and special groups

Depressive disorder is commonly associated with other psychiatric comorbidity. There is some evidence of specificity for the contextual meaning of life events and life difficulties in depressive and anxiety episodes. Hence, depressive episodes are preceded by loss events, and recovery or improvement in such disorders is associated with fresh-start events involving increased hope arising from a lessening of a difficulty or deprivation. Anxiety episodes are preceded by events signalling danger, while recovery or improvement in anxiety disorders is associated with anchoring events that involve increased security. Comorbid anxiety and depressive episodes are preceded by both loss and danger events, while recovery is associated with both fresh-start and anchoring events occurring together (e.g. Brown et al, 1992). Such specificity between life event and diagnosis of anxiety or depressive episodes has not been found in every study (e.g. Leenstra et al, 1995).

Childhood adversity, life events and life difficulties are widely believed to be associated with increased vulnerability to and exacerbation of substance misuse, with or without comorbid depressive disorder. Vulnerability factors such as parental separation and childhood sexual abuse lead to the risk of heavy drinking, while acute life events and chronic life difficulties are related to the onset or exacerbation of heavy drinking in large community samples. Depressive symptoms may have an independent additive effect on the risk of heavy drinking, which may be seen as a form of poor coping influenced by gender and culture (Reference NeffNeff, 1993). A similar picture has been demonstrated with respect to relapse into opiate misuse from abstinence in patients with a life-time history of misuse or dependence (Reference Kosten, Rounsaville and KleberKosten et al, 1986).

An association between life events and the onset of bulimia nervosa has been found in a retrospective community-based sample (Reference Welch, Doll and FairburnWelch et al, 1997). Clinical experience suggests that life events can precipitate the onset of comorbid depressive disorders in patients suffering from bulimia nervosa. Psychological autopsy studies suggest an association between both acute and chronic interpersonal problems and completed young suicide (e.g. Appleby et al, 1999). Interpersonal problems, social withdrawal, rootlessness, acute severe mental disorder and long-term behavioural problems such as substance misuse, repeated deliberate self-harm and personality disorder all appear to add to the risk of suicide (Reference Appleby, Cooper and AmosAppleby et al, 1999).

Finally, life events and life difficulties may play an even greater role in the onset, maintenance, recovery from and adverse consequences of depressive disorder in patients aged over 65 (Reference Harris and BrownHarris & Brown, 1996) and in non-Western settings where there is greater exposure to social adversity (Reference Broadhead and AbasBroadhead & Abas, 1998).

Conclusion

There is sufficient empirical evidence to suggest that the Brown model of social adversity outlined in Fig. 1 identifies psychosocial factors that maintain chronicity or promote recovery from depressive episodes in primary care and psychiatric out-patients with non-psychotic, non-melancholic, first or second depressive episodes. However, there is insufficient evidence that naturally occurring relieving factors or interventions to promote relieving factors alone improve outcome in these patients, or that they are necessary for remission. There is little evidence to support the use of this model in the majority of melancholic, psychotic or frequently recurring depressive episodes.

Limitations of contextual rating in clinical practice

Sources of bias

Two types of bias commonly occur when making contextual ratings of life events and difficulties: search for meaning and recall bias (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997).

If patients have had a bad experience, such as becoming depressed, they may look for reasons and decide that particular social adversity was the cause of their depression. Clinicians should ask themselves why this social adversity was likely to contribute to the patient's depression. They should be non-committal about an association in the patient's mind if either the contextual meaning of the link or its timing (i.e. social adversity preceding a change in symptoms) is unclear.

Recall bias occurs when patients vary in their accuracy or willingness to recall past or current experiences. Induction of depressed mood can lead to a significant increase in reports of past adverse life events and poor-quality social support (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997). The willingness or ability to report life events as a stable personality trait appears to be inherited independently of depressive disorder (Reference Harris and BrownHarris & Brown, 1996; Reference KesslerKessler, 1997).

There are clear difficulties with relying on the contextual method of assessment of social adversity using only the patient's account. The patient's past experience, for example past abuse, or the severity of their current mood disorder may inhibit the person's ability to trust others and to communicate details of their past or current social adversity. Traditional methods of consulting an informant, exploring archival material, such as patient notes, and careful evaluation of the mental state remain helpful additions to the contextual rating of social adversity elicited directly from the patient. Unfortunately, these methods have been relatively underused in research to verify contextual ratings of social adversity and their temporal link to depressive episodes (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997).

Non-clinical samples

The contextual rating method was developed using non-clinical samples with depressive episodes. However, clinical samples may differ from non-clinical ones in several important respects. Non-clinical subjects may think that their depression is not severe enough to warrant seeking help from health professionals or that they can cope without professional help. Therefore, the severity and nature of people's depression and their resources for coping may differ between clinical and non-clinical samples. Such differences may also be reflected in different psychosocial aetiologies of depressive episodes in clinical and non-clinical subjects.

Relationhip between life events and mood

Brown's research has explored associations between life events that are independent of the subject's mood and the onset or chronicity of depressive episodes. However, life events that might be dependent on mood occur frequently before the onset of and during depressive episodes. These may play a key role in precipitating or maintaining depressive episodes, but research has not clarified their importance.

A past history of depressive episodes or current partial remission may complicate an assessment of the independence of a life event in relation to a new depressive episode. People may be less supportive of individuals showing depressed behaviour than they used to be. As a result, the depressed patient is exposed to more interpersonal loss events (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997) and does not benefit from the stress-buffering benefits of social support (Reference Brugha, Bebbington and StretchBrugha et al, 1997). Consequently, patients with a history of depressive disorder are put at increased risk of further depressive relapse, a worsening of depressive symptoms, or increased hopelessness and suicide risk.

Determining causality

Causality may be difficult to establish. Most studies of contextual rating of social adversity have been observational aggregate life-event studies (multiple life events). They interpret temporal associations between life events and depression as indicating that the former cause the latter. This interpretation assumes that life events occur randomly and independently of each other and of other causes of depression, such as genetic susceptibility, alcohol use and social support, but this assumption is unsafe (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997). Other studies assume that these confounding factors have effects additive to those of life events, but again research evidence points to more complex relationships between life events and these other causes of depression (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997). The complexity of these relationships demands experimental studies such as randomised controlled trials (Reference Harris, Brown and RobinsonHarris et al, 1999a ,Reference Harris, Brown and Robinson b ) or prospective study of the adverse effects of a single stressor (e.g. job loss, widowhood; Kessler, 1997) for their clarification. Such studies are rare.

Confounding of stress ratings with outcomes

Information about the impact of a life event on a subject's depressive episode may be used to make ratings of life-event severity. Greater weight might be placed on aspects of the environment that come to light only retrospectively, as the full impact of the depressive episode on the person's life is revealed (Reference KesslerKessler, 1997). Sometimes it is not clear whether the variability between individuals in the risk of developing depressive episodes as a reaction to life events is due to differences in their emotional reactivity to the event, qualitative or quantitative differences in their experience of the stress of the event, or their ability to cope with the event. Given that all of these factors are heavily intertwined, the contextual rating method inevitably has to make some assumptions about the meaning of the life event or difficulty for a given individual.

Nature and role of social support

The precise nature and role of effective social support remain unclear and probably depend greatly on the social context. One of the few prospective longitudinal studies to examine different types of support found that emotional support, rather than confiding alone, predicted good mental health, whereas negative aspects of close interpersonal relationships had an adverse effect on mental health (Reference Stansfeld, Fuhrer and ShipleyStansfeld et al, 1998). Effective social support is usually thought to have a role in protecting the patient from either the onset or the full consequences of depressive disorder in the face of adverse life events or life difficulty (stress buffering). Social support might be protective only in subjects who tend to have long-term feelings of lack of control over their lives pre-dating their depressive disorder (Reference Dalgard, Bjork and TambsDalgard et al, 1995). The most consistent findings linking social support to the onset or outcome of depressive episodes relate to the patient's perception that social support is present and effective. Effective social support may be obtained from one or two intense relationships or it may be the sum of many relationships. Hence, Brugha et al (1997) reported prospectively that the number of social supports predicted recovery from depressive disorder in women in the community, but that the poor quality of a few key relationships was associated with the onset of depressive disorder in women postnatally (Reference Brugha, Sharp and CooperBrugha et al, 1998). Perceptions of effective social support may differ between genders, age groups and cultures. The adverse effects of the lack of social support can also be topic-related. For example, women who developed postnatal depressive disorder regarded their husbands as generally supportive, but not supportive concerning the birth of their last baby (Reference Chapman, Hobfoll and RitterChapman et al, 1997). In some studies, ineffective or abusive relationships with others purporting to be supportive are important precipitants of depressive disorder.

Is contextual rating sufficient?

Some patients with depressive episodes, especially those with an idiosyncratic view of themselves in relation to the world, poor coping strategies or an unstable attachment style, merit more detailed assessment than the contextual rating method provides. Such assessment might include intrapsychic processes, schematic and attributional thinking, cognitive flexibility, problem-solving skills, interpersonal communication skills, personality and behaviours such as avoidance. Such assessments are particularly merited if individual or group psychotherapies are being considered.

Clinical uses of contextual rating

There are five main arguments for including contextual rating of social adversity in the clinical assessment of patients with non-psychotic, non-melancholic depressive episodes.

First, it aids the therapeutic relationship, because the patient feels understood by the clinician. In some cases of depressive disorder, the patient's perception that the GP has accurately understood and explained his or her problems is associated with better short-term outcome, independent of other types of treatment (Reference Downes-Grainger, Morriss and GaskDownes-Grainger et al, 1998). The contextual rating method requires the psychiatrist to understand the patient's past background and current social context in some depth. Promotion of the therapeutic relationship is enhanced if that understanding is fed back to the patient in a way that the patient can comprehend.

Second, tactical decision-making by the clinician is likely to be more effective if the trajectory of the patient's depressive disorder is understood. Patients may not be ready to accept certain types of professional advice and may have misconceptions about health professionals or types of management. An understanding of these issues may be enhanced by contextual rating of the patient's past experience and current social situation. As a result the clinician may find ways of making professional advice more acceptable.

Third, psychosocial options for management can be more precisely specified. At present, effective therapeutic interventions arising from contextual rating are likely to take the form of attempts to reduce the severity or threat of life events and difficulties, to identify actual or potential positive life events, or to improve the quality of social support. Patients will gain more from these interventions if they perceive themselves as playing a central role in identifying and implementing them. Interventions that are entirely attributed by the patient to the efforts of others are unlikely to improve self-efficacy (Reference Johnson, Han and DouglasJohnson et al, 1998).

Fourth, the 12-month prognosis may be more accurate and more specifically related to the patient's current and potential psychosocial situation. The clinician can identify factors of social adversity that increase risk of relapse and help the patient to identify proactively ways of either reducing the potential adversity or improving coping mechanisms.

Finally, the clinician may be able retrospectively to understand the psychosocial factors that have contributed to an unexpected good or bad clinical outcome. This would be important in dealing with complaints or reviewing critical incidents (such as worsening of depressed mood, followed by suicide of a patient with depressive episodes).

Implications for training

The effective use of contextual rating of social adversity by a multi-disciplinary community mental health team would be enhanced by common agreement on factors involved, attitudes towards their usefulness and skills in eliciting clinical material. One-day training courses might include the presentation of a number of cases for group discussion outlining the psychosocial assessment of a case using the factors presented in Fig. 1 and Boxes 1–4. Discussion would focus on how questions were framed to make contextual ratings, examples of good practice and when further questioning or information-gathering from other sources might be required. The assessment should be followed by discussion about the quality and limitations of this information and how it might inform clinical management (e.g. the potential to limit the adverse effects of a current life situation or the opportunity to create a fresh start may become apparent). A conscious effort to incorporate contextual rating of social adversity in the presentation of cases to multi-disciplinary community mental health teams would reinforce their application in routine clinical practice.

Conclusion

Contextual rating of social adversity in depressive disorder is now a well-established research approach that is being applied in clinical practice. It is likely to improve the therapeutic relationship with the patient and suggest useful clinical strategies that might enhance other management approaches, such as antidepressant medication. However, contextual rating should not be applied uncritically. Its benefits will be enhanced if its strengths and limitations are recognised, if it is restricted to non-psychotic and non-melancholic depressive episodes, and if some effort is expended to obtain a common approach to rating among clinicians who work closely together, for example in the same community mental health team.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Maintaining factors for depressive episodes include:

-

a enmeshed intimate relationships

-

b parental indifference before age 17 years

-

c a de-logjamming life event

-

d low educational level

-

e denial of problems.

-

-

2. Relieving factors for depressive episodes include:

-

a neutral life events

-

b anchoring life events

-

c potential fresh-start life events

-

d improved housing

-

e befriending.

-

-

3. Prospective research has shown that life events predict the outcome of:

-

a recurrent depressive episodes

-

b psychotic depressive episodes

-

c non-psychotic depression in non-Western settings

-

d in-patient depressive episodes

-

e suicide in patients with repeated deliberate self-harm.

-

-

4. Possible inaccuracies in the contextual rating of social adversity might occur as a result of:

-

a a retrospective search for meaning

-

b the patient's inherited ability to report life events

-

c a history of past substance misuse

-

d partial remission of depressive episodes

-

e the stress buffering effects of social support.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| a | T | a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | T | b | F | b | T |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | F |

| d | T | d | T | d | F | d | T |

| e | T | e | T | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.