In the learning process, feedback is a process of sharing observations, concerns and suggestions with another person, with the intention of helping them to improve the outcome or their performance. It allows individuals to understand their strengths and weaknesses and highlights areas they need to work on.

Feedback comes in many shapes and forms. The purpose of feedback should be not to judge but to present information (Reference HymanHyman 1980). Effective feedback is one of the fundaments of learning and development. It is difficult to see how doctors in training can improve their skills and behaviours without practising them and receiving feedback on their performance. Giving feedback is an activity that is sometimes omitted or done badly, but it is a skill that can be learned.

Background

Any cyclical system controls itself by monitoring performance results: this is feedback. Where numbers are used, for example an examination score, very simple summative feedback is achieved but little information is passed. The individual does not necessarily learn what they have done well and what was done less well. However, if detailed and useful information is provided as feedback and this influences change then the feedback has been effective and learning has taken place. Feedback is part of the learning cycle and should therefore be considered to be integral to any learning experience. Indeed, formative feedback is an essential part of the learning process and it seeks to evoke response and subsequent change in the learner. It is on formative feedback that we focus here.

Feedback should concentrate on both the good and the not so good aspects of performance. It can originate within the trainee or student or it can come from another, for example a tutor or teacher. Intrinsic feedback comes from awareness of one's own strengths and weaknesses. It involves a degree of insight linked to the skill of accurate and effective self-assessment. Learners should be involved in identifying their own learning needs, as this helps to make the learning experience more relevant and promotes self-assessment and reflection (Reference Kaufman, Mann and JennettKaufman 2000).

Do trainees want feedback and does it make a difference?

Most people have a desire to know how well they are doing at a given task or in their specified role. The implicit expectation of success is fundamental to motivation and effort (Reference AtkinsonAtkinson 1957) and can lead to enhanced performance. Medical students' need for performance feedback has been a constant theme throughout the literature on medical education. Feedback can lead to demonstrable change in performance, for example, higher-quality documentation (Reference OpilaOpila 1997), improved diagnostic skills (Reference Wigton, Patil and HoellerichWigton 1986) and more appropriate use of laboratory tests (Reference Studnicki, Bradham and MarshburnStudnicki 1993).

Trainer and trainee perceptions of feedback

Despite medical trainees' request for feedback, together with evidence that it is beneficial to future performance and its identification as an essential part of the supervisor's or trainer's role (Reference Chur-Hansen and McLeanChur-Hansen 2006), both the literature and personal experience suggest that it is often lacking in practice. Often supervisors believe that they are giving regular feedback to their trainees, but the trainees do not see it this way. There appears to be a long-standing discrepancy between the way trainees and trainers perceive feedback (Reference Gil, Heins and JonesGil 1984).

Trainees' dissatisfaction with feedback

Several studies have highlighted medical trainees' dissatisfaction with the quality of the feedback they receive both at undergraduate and postgraduate level. In one study (Reference Prystowsky and DaRossaPrystowsky 2003), trainees on surgical clerkships rated only 10% of supervisors' comments as ‘helpful’, describing the majority of comments as general and therefore not specific to their own performance. Trainees have highlighted the need for feedback to be relevant to their expected level of performance and competency (Reference Moorehead, Maguire and ThooMoorehead 2004). This is particularly pertinent to contemporary models of competency-based training curricula. In their review of the literature on medical education, McIlwrick and colleagues (2006) concluded that the ‘best-intended feedback may be unhelpful if it is: 1) not descriptive or specific enough, 2) not age appropriate, or 3) mistaken for evaluation’.

Trainers' anxiety about feedback

Although giving feedback is an integral part of the role of the trainer and educational supervisor, trainers may feel uncomfortable about the task, particularly when highlighting areas of deficiency in a student's performance (Reference Gil, Heins and JonesGil 1984). Training trainers and using a set format for feedback can help overcome this discomfort and standardise the way in which feedback is given.

A few years ago, a study in the USA piloted the Instant Feedback Card during a 6-week psychiatry clerkship. The aim of the card was to help students initiate mid-rotation feedback and to help supervisors to standardise and structure that feedback (Reference Bennett, Goldenhar and StanfordBennett 2006). The card included a checklist of clinical competencies and provided both summative and formative feedback. During one placement, students were asked to use the Instant Feedback Card to initiate feedback from their supervisors; during the next placement, they did not use the card. The results showed that 85% of students received feedback when the card was used, compared with 69% when no card was used. The majority of supervisors found the cards ‘useful for stimulating feedback discussion, for reducing the stress of providing feedback, and for getting students to request feedback’. In addition, 84% of students rated the feedback they received using the card as ‘helpful’.

Helpfulness and effectiveness of feedback

For feedback to be effective the individual must reflect on what was positive in their performance and what could be improved in the future. Constructive and effective feedback has been shown to improve learning outcomes, including better assessment marks, in school children and university students (Reference Black and WilliamBlack 1998) and to improve competence (at least in the short term) in medical trainees (Reference Rolfe and McPhersonRolfe 1995). Unfortunately, in practice it is often only the negative aspects that are commented on. This may reduce the repetition of certain mistakes and behaviours but it can also make the trainee feel inadequate. Nevertheless, there are some who argue that their most powerful and formative learning experiences resulted from negative criticism and that praise merely overprotects the trainee and does not show them where they are making errors.

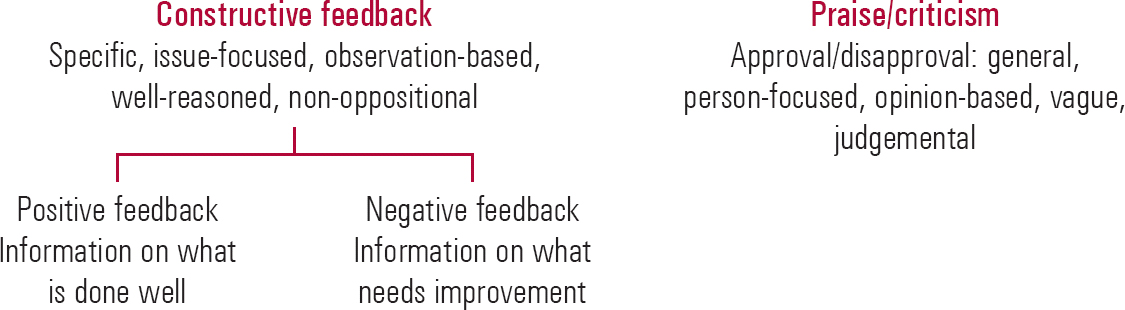

Boehler and colleagues compared giving purely praise with giving constructive performance feedback (Fig. 1). Following completion of a task, half of the students were given general compliments and the other half where given constructive feedback on how to improve in the task. They were then asked to carry out the task again. Those who had received feedback showed improved performance, whereas in the group who had received compliments there was no significant change (Reference Boehler, Rogers and SchwindBoehler 2006).

Principles of constructive feedback

A number of principles govern constructive feedback. The most fundamental are that feedback is for the learner's or trainee's benefit and that it should be offered, not imposed. Feedback involves sharing information rather than giving advice. The amount of information should be tailored to need and the individual must not be overloaded. The information should be checked with the individual, for example ‘How did you feel that went’ rather than ‘That went…’. Do not forget that positive feedback may be confusing if the trainee felt that they performed badly. Feedback should always refer to actions or behaviours rather than to the individual's personality, for example ‘You are always late for clinic – can we look at this?’ (behaviour) rather than ‘You are a lazy doctor’ (personality).

Characteristics of effective feedback

To be of the greatest value, feedback should meet seven fundamental requirements (Box 1). First, it should be timely – it is best given immediately. Obviously, there are times when it is more appropriate to wait – for example, it would be wrong to give feedback in the middle of a patient examination. This would do little for the doctor's confidence and may embarrass both the patient and the doctor.

BOX 1 The seven basic requirements of effective performance feedback

Performance feedback should be:

-

• for the trainee's benefit and solicited not imposed

-

• timely, not delayed

-

• specific, not general

-

• descriptive not evaluative

-

• accurate

-

• not embarrassing

-

• relevant

Second, it is far more beneficial to give specific feedback rather than a more general response. This will ensure that the individual knows exactly what was appropriate or inappropriate, what was good and what was not good. The workplace-based assessments used in UK psychiatric training and the forms and notes that accompany them have exactly this sort of specificity in mind. For example, global responses of ‘That was good’ or ‘That was mostly OK’ are replaced by itemised feedback that highlights exactly the good points and the points that require further development and improvement.

Third, feedback should be descriptive not evaluative – for example ‘I notice that you avoid eye contact with patients’ (descriptive), rather than ‘Your interview skills are poor’ (evaluative).

Fourth, good feedback obviously requires accurate assessment.

Fifth, trainers should avoid personalising the feedback. They should focus on specific items, not on the individual. This is especially important when pointing out weaknesses. The trainee should not be embarrassed through over-effusive praise or diminished by scathing criticism.

Sixth, feedback should be constructive, not destructive. The trainee should see feedback as something helpful and beneficial. A balance must be struck between commenting on what was done well (positive feedback) and what needs further work or development (negative feedback).

Finally, the trainee needs relevant information on how they can improve. Good-quality feedback involves a dialogue between trainer and trainee. If conversation and honest dialogue are fostered, a situation will arise where feedback is actively sought and adult learning flourishes.

Barriers to effective feedback

There are several potential barriers to giving effective feedback and awareness of these can be a first step to overcoming them. The key problems are:

-

• fear of upsetting the trainee or damaging the relationship between trainer and trainee;

-

• fear of doing harm rather than good;

-

• resistance or defensiveness in the trainee: poor handling of feedback by the trainer, for example feedback that is insensitively given is more likely to be ignored; equally, a trainee who finds it difficult to accept feedback is more likely to disregard it;

-

• feedback that is too generalised and not related to specific facts or observations;

-

• feedback that fails to give guidance on how the trainee can change or improve;

-

• inconsistent feedback (from multiple sources or from a single source);

-

• the trainee's lack of respect for the source of the feedback.

The last two points in particular reinforce the need to establish feedback within the context of a relationship built on honesty and mutual respect.

Feedback during workplace-based assessments

The principles above and models below are particularly relevant in the setting of workplace-based assessment. To place an individual workplace-based assessment in context and give appropriate feedback on the trainee's performance it is essential to be certain in one's mind of its purpose: for example, is it an assessment of a general area of the curriculum such as communication skills or does it have a specific objective such as a risk assessment of the trainee? Be clear about what is observed. Taking notes during the performance will improve the accuracy of observation and consequently the quality of subsequent feedback. If a problem is present then it is axiomatic that it must be clearly communicated to and agreed with the trainee, otherwise no plan for improvement can begin.

Models for giving effective feedback

Some of the most common strategies for delivering effective feedback are outlined below.

Pendleton's rules

Pendleton's rules (Box 2) allow both trainee and trainer to comment on how well an activity was performed (Reference Pendleton, Schofield and TatePendleton 1984). The interview follows a format in which the trainee and the trainer state first what they thought was done well, then what they thought could be improved and how this might be achieved. The rules have been criticised for artificially separating the good and poorer parts of performance and for spending too long appraising the positive aspects, leaving little time for suggestions for change.

BOX 2 Pendleton's rules

-

• The trainee performs an activity, e.g. carrying out a risk assessment

-

• The trainee says what they thought they did well, e.g. ‘I think I established a good rapport with the patient’

-

• The trainer comments on what was done well, e.g. ‘You were empathic towards the patient and they appeared relaxed talking to you’

-

• The trainee identifies what was not done so well and how they could improve, e.g. ‘The history I obtained was disjointed. I could use a more structured approach next time’

-

• The trainer comments on the aspects to be improved and offers suggestions in a constructive manner, e.g. ‘It took a long time to establish the circumstances surrounding the overdose. Next time you could try using more closed questions to clarify the situation’

The feedback sandwich

Many people are uncomfortable giving negative feedback. The feedback sandwich (Box 3) allows a criticism to be ‘sandwiched’ between two items of praise. It is particularly useful at the start of a new trainer–trainee relationship, and it allows the development and honing of specific skills and behaviours. The trainer begins by commenting on a positive area of an activity and praises the trainee on this. The ‘meat’ of the sandwich is the criticism; this should be constructive and provide suggestions on what could be changed. The trainer then ends the feedback with another positive comment on the trainee's performance.

BOX 3 The feedback sandwich

-

• First, the trainer gives a positive comment, e.g.' I especially liked the way you reflected on how the patient was feeling at that time'

-

• Then the trainer comments on an area that needs change and advises how to achieve it, e.g. ‘The patient was still crying when you moved on to the physical exam. Perhaps next time it would help to wait a little longer’

-

• The trainer finishes with another positive comment, e.g. ‘I liked the way you included the patient in decisions about the management of her disorder’

Silverman's SET–GO

Also known as the Calgary–Cambridge method (Reference Silverman, Draper and KurtzSilverman 1997), Silverman's SET–GO (Box 4) involves descriptive feedback during which the trainee comments on what they experienced while carrying out a task. The task is often videotaped, which allows the trainee to reflect and comment on what they see when reviewing the tape. The trainee discusses with the trainer what they were thinking during the task and acknowledges any difficulties. An aim or goal is clarified and ways of achieving this are discussed. This method can be used in teaching sessions where a peer group review the trainee's tape.

BOX 4 Silverman's SET–GO

-

• What the trainee Saw – this should be descriptive, specific and non-judgemental, e.g. ‘The patient became very upset and tearful when I talked about the diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder’

-

• What Else they saw – again, descriptive, e.g. ‘I allowed the patient to calm down before continuing talking’

-

• What the trainee Thought at the time – reflection, acknowledgement and problem-solving, e.g. ‘I was aware the news was distressing the patient and was concerned he wouldn't remember a lot about our conversation. I could have given him written information’

-

• Clarify the Goal, e.g. discussing a diagnosis with a patient

-

• Explore Offers of how to achieve the goal, e.g. clarifying what the patient believes is wrong and what they understand by the diagnosis given, and discussing the treatment options

The six-step (problem-solving) method

This step-wise approach to delivering feedback is particularly effective when it is necessary to reach agreement on what has gone wrong with the trainee's performance and where the problem lies (Box 5). First, the trainer establishes a rapport with the trainee. The trainee then undertakes a task, the aim or outcome of which is identified beforehand. The trainer observes the task and gives feedback to the trainee. The trainer may need to be flexible in their approach to ensure that the trainee understands the trainer's observations and suggestions for improvement. The six-step method is described well by Reference Chambers and WallChambers (1999: pp. 131–143).

BOX 5 The six‐step (problem‐solving) method

When a problem in the trainee's performance is identified, the six steps are:

-

1 problem presented (to the trainee by the trainer)

-

2 problem discussed

-

3 problem agreed

-

4 solution proposed

-

5 solution discussed

-

6 solution agreed

For the method to work it is essential that the trainer:

-

• is able to connect – establish a rapport with the trainee

-

• has identified a clear outcome in advance, i.e. the trainee must agree that there is a problem and the agreement should not be diluted or obscured by external factors such as the trainee's counter-arguments

-

• transmits a clear message: the problem cannot be resolved unless the trainee understands it and agrees with it

-

• is flexible – using different techniques to communicate the message

Feedback as a gift

Feedback as a gift is a semi-formal and simplified amalgam of the Pendleton and Silverman models. Continuing the culinary metaphor, feedback as a gift (Box 6) resembles an open sandwich. First, the trainer highlights an area in which the trainee did well, then an area in which they did not perform to such a high standard. Finally, the trainer highlights an area of weakness in the trainee's performance and suggests how it might be improved.

BOX 6 Feedback as a gift

The trainer comments on:

-

• something good that the trainee needs to keep doing, e.g. ‘I liked the way you asked the patient what she wanted to achieve from the session’

-

• something that distracts the trainee from their strengths, e.g. ‘I feel that the patient was not clear about what was expected from her for the next session’

-

• something that is a weakness, with a suggestion for improvement, e.g. ‘Towards the end of the session you could summarise what has been discussed and clarify any unclear areas’

The Chicago model

The six-step Chicago model (Reference Brukner, Altkorn and CookBrukner 1999) is similar to other methods but has the great advantage of starting with a recapitulation of the aims and objectives that the trainee is supposed to be addressing (Box 7).

BOX 7 The Chicago model

The six steps that the trainer takes are to:

-

1 Review the trainee's aims and objectives

-

2 Give interim feedback of a positive nature

-

3 Ask the trainee to give their own appraisal of their performance

-

4 Give feedback focusing on behaviour rather than on personality (what happened, not the trainer's opinions or what the trainer thinks might have happened or been about to happen – this is particularly important in workplace-based assessment)

-

5 Give specific examples to illustrate (aided greatly by taking notes during observation)

-

6 Suggest specific strategies for improvement

Dealing with difficulty

Telling a trainee that they are doing well is very satisfying. However, telling a trainee that there are problems with their performance can be very difficult. It is not always easy to give feedback that separates the performance from the individual. Making apparently intrusive comments can be awkward and individual trainees will respond in different ways. Giving the trainee space in which to express themselves and their feelings is essential. They should not be interrupted or confronted at such times, even if their response is aggressive, defensive or tearful. When they are in control of themselves they should be asked how they would describe what they are doing and what they would see as a positive way forward.

Practical issues may need to be addressed, such as not allowing the trainee to perform a particular task until the trainer has had the opportunity to give them detailed feedback followed by a reassessment.

But the main points that trainers should remember are to:

-

• do it immediately, not put it off

-

• find out or have to hand the facts

-

• share the problem

-

• explain the problem

-

• give support

-

• document what they say and do.

Feedback using other communication tools

Sometimes it is necessary or appropriate to give feedback in ways that are not face to face.

Telephone feedback

Telephone feedback is difficult for trainer and trainee. As there are no non-verbal cues, it is necessary to be extremely sensitive to changes in voice or hesitations that may suggest doubt or disagreement. Many trainees are reluctant to ask questions for clarification because they seem repetitive or foolish. Voices sound different over the telephone and many statements that are delivered comfortably face to face sound aggressive or rude down the phone line. International calls can introduce an unfortunate dimension of delay and sometimes echo into an already difficult situation. If feedback has to be given by telephone the trainer should keep a short written record of the conversation for future reference and in case of misunderstandings.

Written feedback

Written feedback may be needed even when the trainee is seen regularly. The correspondence must be clear, concise and supportive. If in doubt, trainers should ask a colleague to see how the letter ‘reads’ to them. It can be more difficult to express thoughts in the written rather than the spoken word. It should be remembered that a trainee from another culture may misunderstand the nuances of one's language. Letters are a very formal and strong method of communication; the same content may lose some of its formality in a fax.

Email feedback

Email can be used for quick, relatively informal communications. However, the very lack of social niceties that is common in emails may give rise to misinterpretation and it may again be wise to check content with a colleague. The send button should never be pressed without due thought!

Conclusions

In the UK, trainees in psychiatry have always viewed feedback as desirable (Reference Day and BrownDay 2000) and it is now even more important after the adoption of workplace-based assessment. The greatest value of the latter as an educational tool is its formative assessment of the real performance of doctors at their service base. It allows areas of performance to be observed and clear, regular feedback offered that appropriately adjusts to the trainee's learning objectives and plan.

In giving good feedback the supervisor or trainer is helping the trainee to change: feedback is a powerful instrument which, if used wisely and well, can further a trainee's personal and professional development. It is clear that the ability to give feedback is a core skill for trainers. This underlines the need to include training in feedback skills in basic ‘training for trainers’. This view is reinforced by both the Royal College of Psychiatrists, which has commissioned a CPD online module on the subject (Reference Oakley and OyebodeOakley 2008), and the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board. The latter lists as one of the principles of assessment that ‘assessments must provide relevant feedback’, highlighting the shortcomings of summative assessments such as the traditional ‘structured trainers report’, which specifies only failing standards and thus limits the opportunity for improvement in performance (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board 2005: p. 11).

MCQs

-

1 Feedback is:

-

a a judgement

-

b always positive

-

c not useful in the learning process

-

d a process that is intended to improve performance

-

e omitted in the modern postgraduate educational process.

-

-

2 Characteristics of effective feedback include:

-

a destructive comments

-

b relevance

-

c evaluative comments

-

d delayed delivery

-

e general comments.

-

-

3 Barriers to effective feedback include:

-

a fear of upsetting the trainer

-

b resistance in the trainee

-

c feedback being specific to the trainee

-

d consistent feedback

-

e respect between trainee and trainer.

-

-

4 The following are models for giving feedback:

-

a the feedback sandwich

-

b Penfold's rules

-

c Goldman's SET–GO

-

d the San Diego model

-

e the twelve-step method.

-

-

5 When dealing with difficulties:

-

a it is best to delay giving feedback

-

b avoid the trainee

-

c ignore the problem

-

d keep the problem to yourself

-

e document what you do.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | f | a | f | a | t | a | f |

| b | f | b | t | b | t | b | f | b | f |

| c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f |

| d | t | d | f | d | f | d | f | d | f |

| e | f | e | f | e | f | e | f | e | t |

FIG 1 Feedback v. praise and criticism.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.