The primacy of a team approach to caring for and treating patients, based on shared goals, competencies and capabilities, is a central clinical and political imperative (e.g. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health 2001; Reference HopeHope 2004; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2005). Opposing this aim may be an inevitable tendency for different professions to organise their interventions separately and to employ different strategies, with limited clinical and conceptual coherence. Routine clinical meetings such as ward rounds often involve discussion along behavioural and symptomatic lines, and different professions may contribute tangentially: art therapists might comment on the possible meaning of created artefacts, and psychologists may use terminology and concepts of cognitive–behavioural therapy to help explain behaviour. Alternatively, knowledge of all of a patient's interactions with other patients and staff, as well as with past and present external others, can potentially help staff to develop a theory of the patient's mind. The task of exchanging information derived from numerous, often intense experiences with the patient in the clinical setting should be undertaken by all members of the multidisciplinary team who work with them.

Repeated dysfunctional patterns of behaviour, which are a part of mental disorder, underlie many problems. Patients may not be able to access and take advantage of therapeutic interventions because of difficulties in their interpersonal and intrapersonal functioning. In particular, those who have suffered from abuse or neglect in early childhood, and perhaps also experienced continuing victimisation as adults, may, without realising what they are doing, influence their environment so as to time and again repeat the cycle of previous adverse experiences. Patients who communicate through action and impact are particularly prominent in forensic practice, but they are also present in all areas of psychiatric work. We can often recognise them by the strong emotions they are able to generate in staff. For example, some are able to divide the team's views on how they should be treated, or they elicit especially positive (or negative) feelings in a particular therapist.

What are interpersonal dynamics?

Relationships

The ability to develop and maintain effective relationships with others is central to our satisfactory functioning as human beings; however, many patients, not just those who are formally diagnosed with personality disorder, are impaired in this respect. Those who may benefit from an assessment of their interpersonal dynamic framework, followed by appropriate intervention, have a limited repertoire of behaviour and expression in relation to others. Most of us are able to develop our interactions and successfully adapt, as we mature, to the changing circumstances of our lives. For some patients, patterns get stuck. They can become increasingly dysfunctional and lead, both for individuals experiencing active mental illness and for those who have apparently recovered, to persistent interpersonal difficulties.

Caring for patients

The problems that some patients experience when interacting with others are particularly exacerbated when they are in need and enter a relationship of dependency, as with a professional carer, whether in the ward or the community. In such cases, the patient brings to or imposes upon the relationship their needs and intense feelings. This may affect all the staff that come into contact with the patient and distract the team from the reality-oriented nature of the relationship, i.e. that the patient is ill and needs help. Such sustained and powerful emotional impacts may evoke dysfunctional responses in any member of the team, particularly staff members who are close to the patient for long periods of time.

Many patients have only limited capacity to represent, think about and elaborate their experiences, feelings and impulses, and it is therefore the task of all mental health professionals involved to be able to develop the capacity to carry this missing or deficient psychological function on the patients' behalf, to mentalise their interpersonal predicament (Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman 2004). For the caring team, a shared awareness of the interpersonal dynamics and their effects has the potential to keep the focus on working together, to provide an awareness of why we are unable to carry out our roles if the patient manifests a profound distortion, and allows us to develop more effective interventions.

Theoretical and empirical background

The interpersonal circle

Reference BirtchnellBirtchnell (1993) described how relating, an activity which is universal across the animal kingdom, confers advantages upon those who are able to successfully engage in it. He outlined how relationships could be described by two axes: proximity (horizontal) and power (vertical). Reference Freud and StracheyFreud (1950) had previously proposed that there were two types of human instinct: sexual and destructive, which corresponded to the horizontal axis, and power relationships, represented by the vertical axis.

Freud's work was taken forward by Harry Stack Reference SullivanSullivan (1953), a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, who understood that infants need emotional contact with others and that early perceptions of interpersonal interactions, initially with parents, greatly influence adult personality development. His theory recognised that everyone fundamentally requires love and power in order to be secure and free from anxiety. He also emphasised how important it is for mental health professionals to be able to understand the world as the patient sees it. The ‘object relations’ school of psychoanalytic theory, further developing this strand of work, highlighted the paramount importance of attachment (Reference BowlbyBowlby 1969) as well as the development of autonomy for normal development (Reference Greenberg and MitchellGreenberg 1983). However, psychoanalysis was eventually marginalised through not being included in the DSM–III (American Psychiatric Association 1980) as well as being neglected by most academic psychologists due to the perceived lack of scientific evidence behind it.

Henry Reference MurrayMurray (1938), an academic psychologist, acknowledged his debt to psychoanalytic theoreticians and pioneered empirical research on psychoanalytic concepts. He thereby produced a list of human needs, which he saw as themes underlying human behaviour, to parallel analytic drives. Reference BenjaminBenjamin (1996, p. 21) has outlined how ‘Murray systematically organized ideas about how biological drives can interact with interpersonal experiences to create a “personality”.’ Timothy Reference LearyLeary (1957) conducted empirical research and arranged a selection of Murray's needs around two perpendicular axes (love/hate and dominate/ submit) to form the basis of the interpersonal circle. This arrangement, which describes a range of possible interactions that can occur within a relationship, is also known as a circumplex (Reference Guttman and CattellGuttman 1966). Reference SchaeferSchaefer (1965) proposed a vertical axis, modelled on parenting behaviours, which is defined in terms of allowing autonomy v. control. Circular models of this type have been scientifically validated (Reference SchaeferSchaefer 1965; Reference Wiggins, Kendall and ButcherWiggins 1982).

Reference AllportAllport (1937) defined personality as ‘the dynamic organization within the individual of those psychophysical systems that determine his unique adjustment to his environment’, and used the term ‘dynamics’ to refer to an individual's goals and purposes. Reference BenjaminBenjamin (1996), drawing on both personality theory and the interpersonal circle, produced the Structural Analysis of Social Behaviour (SASB) model, one of the main sources for the work described in this article. She wanted to develop a more objective understanding of psychopathology in interpersonal terms, and demonstrated distinctive interpersonal profiles for the different types of personality disorder. In the forensic context, Reference BlackburnBlackburn (1998) has used the interpersonal circle to examine the relationship between interpersonal style and criminality in both mentally ill patients and those with personality disorder, finding that offenders with extensive criminal careers have a more dominant and coercive interpersonal style. The Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnostics (OPD) Task Force (2001, 2007), heavily influenced by the SASB, used an interpersonal circle to describe the many possible interactions that may occur within a relationship between a patient and staff members.

The interpersonal circle in practice

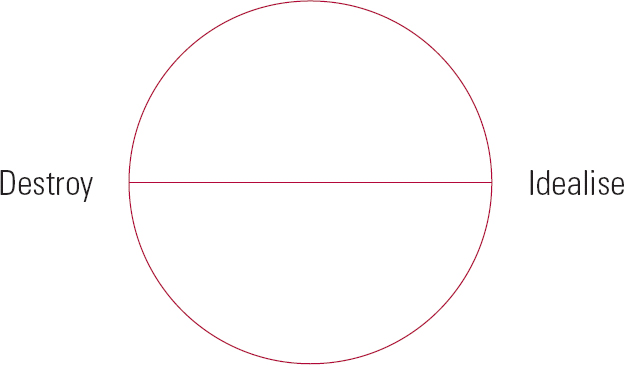

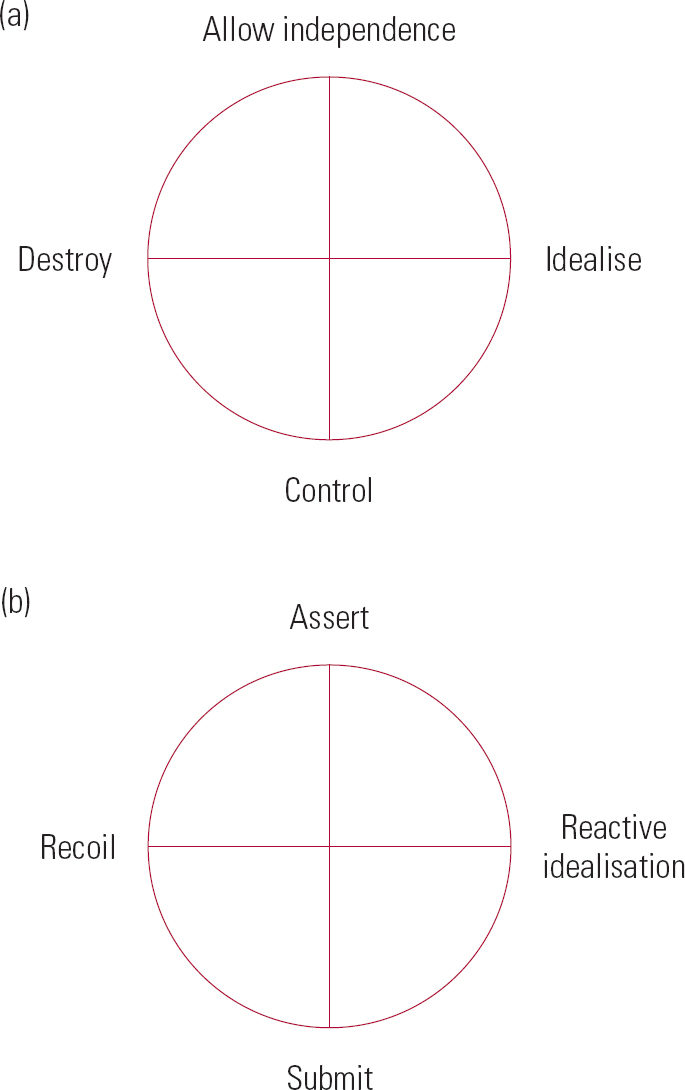

The type of interpersonal circle employed by clinicians should, for ease of use and to assist formulation, reflect the psychopathology of the patient group being assessed. The interpersonal circle we have developed, based on the above precedents, has been adapted and tailored to the needs of our work in a forensic unit: a horizontal axis with ‘destroy’ and ‘idealise’ as the opposing polarities (Fig. 1). This is combined with a vertical axis which ranges from ‘allow independence’ to ‘control’ (Fig. 2(a)).

FIG 1 The interpersonal circle: active layer, horizontal axis.

FIG 2 The interpersonal circle: (a) active and (b) reactive layers, horizontal and vertical axes.

The interactions described by the interpersonal circle focus in two directions, the ‘other’ or ‘active’, and on the ‘self’ or ‘reactive’ (Reference BenjaminBenjamin 1996). The active indicates how the self perceives the behaviour or attitudes of the other, the reactive is how the self responds to these perceptions. There are therefore two layers to the interpersonal circle: the active layer (Fig. 2(a)) and the reactive layer (Fig. 2(b)).

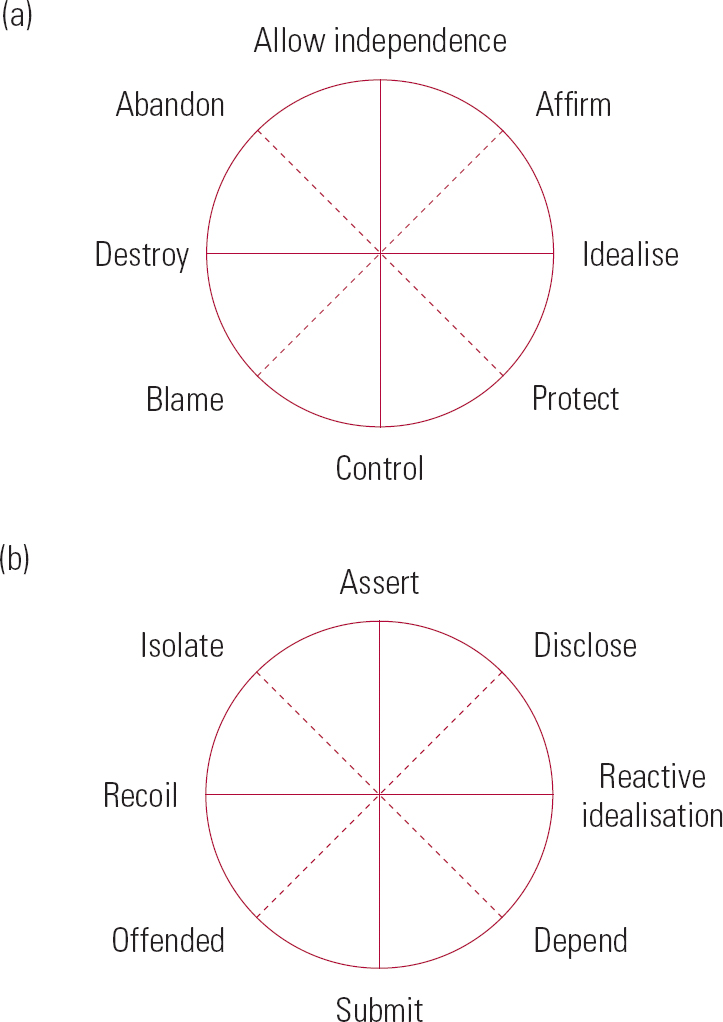

Further points are added around the circle to describe the interaction in more detail (Fig. 3).

FIG 3 The interpersonal circle: (a) active and (b) reactive layers, horizontal and vertical axes with intermediate points.

To help professionals determine how patients and staff experience their interpersonal relations, the list of possible interactions can be expanded and the structure altered by listing them to form a type of menu from which professionals may choose when describing an interaction (OPD Task Force, 2001, 2008). The modified list we present here (Box 1) has 28 points in total, 14 points around each circle (1–14 are active, 15–28 are reactive).

BOX 1 List of items for interpersonal perspectives

| Active circle | Reactive circle |

|---|---|

| 1 Allowing too much independence | 15 Defying and opposing |

| 2 Accepting and admiring | 16 Insisting on their position |

| 3 Attending to and caring | 17 Revealing and exposing |

| 4 Treating him/herself as special | 18 Pouring out concerns and anxieties |

| 5 Over-estimating and idealising | 19 Relying on |

| 6 Instructing and patronising | 20 Clinging |

| 7 Domineering and overwhelming | 21 Giving up in despair |

| 8 Demanding and imposing | 22 Appeasing and complying |

| 9 Accusing | 23 Indignant and self-justifying |

| 10 Putting down and humiliating | 24 Hurt and touchy |

| 11 Intimidating and attacking | 25 Running away |

| 12 Rejecting | 26 Showing disgust |

| 13 Abandoning | 27 Cutting off contact |

| 14 Ignoring | 28 Keeping up a barrier |

The four interpersonal perspectives

The OPD Task Force further developed the work of Reference BenjaminBenjamin (1996), taking into account the work of others who have also outlined methods of observing personal interactions (Reference Strupp and BinderStrupp 1984; Reference Weiss and SampsonWeiss 1986; Hoffmann 1988; Reference Luborsky and Crits-ChristophLuborsky 1990; Reference HorowitzHorowitz 1991), and describe interpersonal relations using four perspectives (Box 2). This framework concerns the transference–countertransference configurations enacted between each patient and those members of staff involved in their treatment as experienced in the care setting (Reference Kirtchuk, Reiss, Gordon, Kirtchuk and GordonKirtchuk 2008).

BOX 2 The four interpersonal perspectives

-

A The patient, time and again, experiences others in such a way that they are … (focus is on the other – active)

-

B The patient, time and again, experiences themself in such a way that they are … (focus is on the self – reactive)

-

C Others, the investigator included, time and again experience that the patient is … (focus is on the other – active)

-

D Others, the investigator included, time and again experience themselves in their interaction with the patient that they are … (focus is on the self – reactive)

Each party in an interaction has two types of experience. They have an experience of each other which can be described as an active experience, and also an experience of themselves in response to their contact with each other, which can be described as a reactive focus on the self. The whole forms a reliable and valid empirical structure to determine stable but dysfunctional patterns in relationships (Reference Cierpka, Grande and RudolfCierpka 2007).

Application in clinical practice: the interpersonal dynamics consultation

The interpersonal dynamics for any particular patient should be assessed at a multidisciplinary team meeting. Participants should include staff members who are personally involved with the patient, as well as a facilitator from outside the team who has expertise in the approach and skills in working with psychodynamics. It is important that experiences are shared because the patient may feel and behave differently towards various carers. Those who are closely involved with the patient may find it difficult to determine precisely what is happening in their interpersonal relationship, and discussion with others is very helpful to identify the relevant features appropriately. The process is non-hierarchical as all perceptions and experiences are valid. The meeting itself comprises four stages: the initial part is a presentation of background information; next the interpersonal dynamics are determined; then a formulation is produced; and finally the strategy for care is reviewed (Box 3). We currently undertake this process in two meetings of up to 1 h each: in the first meeting the first three stages take place, between the meetings the formulation is written up, and the second meeting is for the review of clinical care.

Background information

To begin, the problem with which the team is dealing is outlined. The patient's background history is then summarised, particularly emphasising early interpersonal relationships with parental figures and siblings, and adding relevant information about adult relationship patterns. The patient's offending history, if any, is also detailed, including its nature, the background circumstances, the relevant dates and the medicolegal outcome. Then an overview of the current pattern of interpersonal relations is produced, with an emphasis on the current difficulties in case management. Appropriate sources of information for this assessment include case records, collateral interviews with relevant informants, the staff themselves and patient interview. If any material is not available which would have been relevant to the assessment, this is noted and consideration is given to how and when this material can be found.

Assessment of interpersonal dynamics

In this part of the process the team members analyse and record the interpersonal dynamics on the basis of the information that is already available to them about the patient. Further details may emerge as the team reflects what is happening and a lively, respectful discussion is appropriate.

Using a list such as that in Box 1, the team identifies as many items as possible on the two interpersonal circles that describe the patient's dysfunctional relationship patterns as well as the corresponding perceptions and responses of the staff, and then makes a more rigorous selection of those items which are the most prominent. The process is carried out for each of the four interpersonal perspectives (Box 2). The evidence for each item listed is recorded. Once the group has identified as many items as it considers appropriate for each perspective, they are put in order of perceived strength and the number reduced, usually to about three. This process needs to be carefully monitored and assisted by the external facilitator as staff will need a trusting, supportive environment to disclose their own perceptions of the patient and their own consequent experiences.

Formulation

On the basis of this refined selection of items, the team attempts to make a dynamic formulation of the dysfunctional pattern of interactions which includes the ‘here and now’, early development, adult life, and, if there is one, the interpersonal nature of the index offence. The overall aim is the identification of maladaptive or collusive patterns of relatedness in which the staff may have been vulnerable to being ‘caught up’, unwillingly reinforcing the patient's destructive behavioural pattern. This process does not result in the patient being blamed – indeed, in many cases a problematic professional response may arise out of the staff member's own difficulties; rather, it promotes understanding, thereby allowing one or more therapeutic strategies to be developed.

Intervention

The final part of the meeting is a discussion about the change of strategy that can be adopted by members of the multidisciplinary team with regard to their own interactions with the patient.

We are currently exploring ways in which patients themselves can be more involved in the entire process, through assisting and improving the assessment with an initial interview.

Case vignette

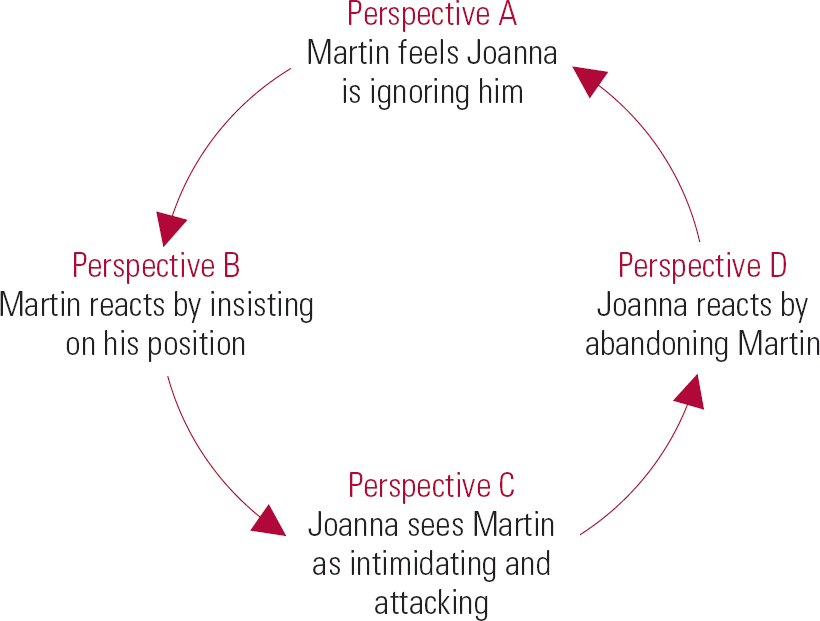

The above framework is illustrated by the following fictional interaction between two people: Joanna, a member of staff, and Martin, an in-patient.

Martin has a childhood history of neglect and abandonment by both parents. As an infant and child he was cared for by a strict aunt who left him mainly to his own devices. One strategy he used to cope at that time in his life was by becoming very ‘independent’ for his age.

Now 30, Martin has a history of a relapsing psychotic mental illness dating back almost 10 years. He was admitted to an acute psychiatric unit several months ago and has made a slow but steady response to his treatment. Although he apparently adhered to his medication regimen, he hardly engaged with his therapeutic programme, preferring to spend most of the day in his room, minimising his contact with staff. Nurses and occupational therapists dealt with that difficulty by trying to encourage him to participate in ward activities but very quickly felt that they were being too intrusive. This has become an identified problem for Martin's care.

One day Joanna went to Martin's room at 10:00 and invited him to attend the ‘plan of the day’ meeting in the ward's communal area. Martin responded by saying ‘Don't disturb me with this stupid request’. He perceived the invitation to be an intrusive demand that did not take account of his real needs, because he thought that the staff did not really care about him (he had recently said to another member of staff ‘None of you really care about me’).

On the basis of this interaction, the team adds the following items to perspective A (how the patient repeatedly perceives others): ‘ignoring’ (item 14) and ‘demanding and imposing’ (item 8).

Martin also replied to Joanna, ‘I'll decide what I come to’.

The team adds to perspective B (how the patient regularly experiences himself) the item ‘insisting on his position’ (item 16).

Joanna, in turn, perceived the patient as being very rude and aggressive.

The team adds to perspective C (how others, the staff included, regularly perceive the patient) ‘intimidating and attacking’ (item 11).

Joanna therefore left the room and did not insist any further. She experienced a mixture of feelings: being offended and wanting to leave Martin to his own devices, while at the same time sorry and guilty for being excessively intrusive with a fragile and vulnerable person.

The team adds to perspective D (how others, the staff included, regularly experience themselves) the items ‘hurt and touchy’ (item 24), ‘abandoning’ (item 13) and ‘attending to and caring’ (item 3).

Ultimately, in accordance with these perceptions, Joanna decided that Martin's needs would best be met if she did not ask him to attend the rest of the day's therapeutic programme.

The formulation highlighted how Joanna's response reinforces the sense of abandonment and the actual neglect of his social and therapeutic needs that Martin has experienced all his life, and further outlined how his provocation of the very behaviour he complains about functions as a defence against forming relationships. The dysfunctional nature of this interaction is clearly exposed when Joanna's response to how she feels when she is with Martin results in a situation which anchors his distorted perception of others. Once again his genuine need to engage with the therapeutic programme is neglected, which closes a dysfunctional cycle of interpersonal dynamics (Fig. 4; the circle is completed as perspective D feeds into perspective A).

FIG 4 Case vignette: the dysfunctional cycle.

Once the team realised how their response was repeating the vicious cycle of Martin's life, they were able to produce an intervention which could be incorporated into his care plan. In this case it was decided that the team would work with Martin on assessing what his needs for daytime activity were, involving him in the process so that he could see how the staff were caring for him, and supporting him to develop functional relationships with them. Staff would then agree a timetable with Martin and help him to take part in it in a way which engaged with his desire for independence, not opposing or confronting it.

Multidisciplinary teamwork

Working with interpersonal dynamics allows the different professionals involved in a patient's care to coordinate their separate views based on a shared set of concepts and a common language. By doing this, all staff, even if they come from different theoretical backgrounds, can work in partnership to interpret and understand the observed behaviour of patients.

The discussion encourages the full participation and involvement of all members of staff. During a meeting about interpersonal dynamics, everyone who has had involvement with the patient is invited to discuss their different viewpoints of the interpersonal relationship on the basis of their experience of the patient in their respective clinical functions. Different members of staff may evoke contrasting patterns of interaction, depending on their role and/or personal characteristics.

During the process, colleagues are able to identify in one another behaviours and responses which may indicate underlying attitudes and feelings towards patients. People sometimes may find it very difficult to identify or acknowledge their own emotional responses, but can more easily see and decode the observed behaviour and comments of others. Although sometimes, particularly initially, this process can be uncomfortable, over time group members, when appropriately supported, come to value that others can be more aware of feelings which one is unaware of oneself.

Most importantly, team members are provided with a means of validating the meaning of their observations and emotional responses and of comparing and exploring them with colleagues. The process also allows communication about interpersonal relationships with patients to be a shared focus of clinical work, using readily available material.

Training

The assessment of interpersonal dynamics can be conducted by staff acting at all levels. Team members require only a minimal amount of background knowledge to effectively contribute to the process. The language in which the structured instrument is expressed is uncomplicated and jargon free. It can be adapted through the use of colloquialisms shared by the team, if appropriate. All the information necessary to conduct the assessment, apart from the information about the patient, is contained on two sheets of A4 paper which should be in front of all participants during the process. The technique is therefore simple to pick up and easily applied. Only very brief training is required for staff (who may have little, if any, previous psychodynamic experience) to be involved effectively. This may be conducted in an interactive workshop format lasting 90 minutes, covering an introduction to the theoretical background to the approach, together with a sample case.

Staff responsible for more complex aspects of the assessment, for example those involved with leading the team through the process and those responsible for developing the formulation, would require more extensive training and would need experience in psychotherapeutic techniques. Reference TempleTemple (1999) has outlined how mental health teams may be helped enormously by the resources provided by a consultant psychiatrist who has an appropriate level of psychodynamic skills, and we consider that a model training programme for such a professional would take 6 months. It would involve 3 days of formal training plus attendance and presentations at a weekly educational seminar. Although there are barriers to training in this area (Reference TaylorTaylor 2001), at our hospital we have established a workshop in interpersonal dynamics for psychiatry trainees, and this has been evaluated positively.

Assessment and management of risk

Risk assessment using instruments such as the Historical–Clinical–Risk Management–20 (HCR–20; Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster 1997) will determine the areas that need attention and thereby indicate which treatment programmes need to be applied. However, they do not supply a way of implementing this treatment when progress is blocked because of a patient's repetitive and counterproductive pattern of behaviour. An understanding of the interpersonal dynamics involved not only has the potential to aid access to appropriate therapies, thereby having the capacity to reduce risk, but it can also identify the patient's dynamic risk signature. For example, some individuals may be liable to act out when they perceive that they are unjustly accused, others may respond aversely if they perceive abandonment.

Conclusions

We have outlined how it is possible to integrate psychodynamic working into the clinical practice of a busy, multidisciplinary mental health team by giving staff a framework through which they can productively use information that otherwise might not be shared, to improve their understanding of important clinical issues. The interpersonal dynamics framework follows a structured format, but allows participants to include all relevant factors within it as they compare their views on the various perspectives. Material often emerges in the discussion in response to the comments of others. Information gathered is put into the required format as the process progresses.

This method is accessible. All members of staff are rapidly able to understand the framework and make a contribution. The fact that there is a ‘menu’ that conveys different emotional actions and reactions facilitates the creation of a safer space for staff to talk about their feelings without experiencing that they are disclosing things which they might feel are too personal. However, an experienced therapist is required to support the group by creating a safe atmosphere for staff to divulge their innermost sentiments about the patient, as well as facilitating a full formulation which takes these revelations out of the realm of the personal and places them firmly in a professional mental health context. If team members understand the dysfunctional dynamics which may be present, and are able to place them in the context of the patient's life, index offence and level of risk, a vital step in promoting a collaborative treatment project which is both therapeutic and safe has been taken.

Effective understanding of patient behaviour by caring staff is the key to providing a therapeutic environment. A systematic and integrated framework for viewing patients which is shared by the whole team and leads to a consistent way of behaving towards them also has the potential to improve patients' responsiveness to a wide range of therapeutic interventions which are targeted at specific aspects of their psychopathology.

This method, by systematising the collection of information about staff's own emotional responses in a supportive framework, validates these emotional reactions as part of a scientific discourse, provides an effective forum for staff to discuss their feelings, examines how they are being formed in response to what the patient is doing, and then makes sure that staff's behaviour in response to the patient is not dysfunctional. The final formulation comprised a framework within which each professional can act in accordance with their own way of working.

When organised together with well-established, effective, reflective practice, as well as community meetings able to offer an opportunity to look at institutional and team dynamics, interpersonal dynamics is part of a structure which can contribute to the development and establishment of a therapeutic milieu in all settings where mental healthcare is provided.

MCQs

-

1 The interpersonal circle:

-

a is based on the work of Jung

-

b has a horizontal axis and a vertical axis

-

c only describes dysfunctional interactions

-

d is not scientifically validated

-

e must have 15 points around it.

-

-

2 The four interpersonal perspectives:

-

a are all active experiences

-

b occur when four people interact

-

c are usually unconscious

-

d are divided between active and reactive experiences

-

e are the four main points of the interpersonal circle.

-

-

3 Assessment of interpersonal dynamics:

-

a is best done by one member of the team working alone

-

b does not need any review of background information

-

c should respect the views of all team members

-

d requires all involved to have undergone lengthy training

-

e is subjective and therefore unreliable.

-

-

4 Multidisciplinary team members:

-

a benefit from a shared understanding of the patient to work effectively

-

b should ignore their emotional responses to patients

-

c are professionals and therefore always work in the interests of their patients

-

d should give up previous ways of working when using interpersonal dynamics

-

e should regard a split in views as an indication that the team needs an awayday.

-

-

5 Training in interpersonal dynamics:

-

a requires the learning of a lot of technical jargon

-

b should only be undertaken by the team psychiatrist and psychologist

-

c requires the staff member to have undertaken personal analysis

-

d may be undertaken at a variety of levels

-

e is not useful for psychiatrists in training.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | f | a | f | a | t | a | f |

| b | t | b | f | b | f | b | f | b | f |

| c | f | c | f | c | t | c | f | c | f |

| d | f | d | t | d | f | d | f | d | t |

| e | f | e | f | e | f | e | f | e | f |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Matthias Von der Tann, Dr Oliver Dale and Mr John Gordon for their contributions to the writing of this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.