Late-life depressive disorder, occurring in those over the age of 60 years, is common, affecting over 9% of people living in the community (Reference Beekman, Copeland and PrinceBeekman 1999; Reference McDougall, Matthews and KvaalMcDougall 2007) and 25% of those living in institutions (Reference McDougall, Matthews and KvaalMcDougall 2007). It is associated with reduced quality of life and high morbidity (Reference Alexopoulos and KellyAlexopoulos 2009a; Reference Volicer, Frijters and Van der SteenVolicer 2012). It has a detrimental impact on recovery from physical illness (patients with moderate to severe depression have been shown to have delayed recovery following hip fracture (Reference Morghen, Gentile and RicciMorghen 2011)) and leads to increased mortality through suicide and self-neglect (Reference Djernes, Gulmann and FoldagerDjernes 2011).

Diagnosis and aetiology

Diagnosis is based on standard ICD-10 or DSM-IV criteria (World Health Organization 1992; American Psychiatric Association 1994). However, there may be subtle differences in clinical presentation, with higher rates of somatic symptoms, anxiety and psychomotor retardation, reduced interest in activities and poorer executive dysfunction compared with younger age groups. These symptoms are not sufficiently different or reliable to classify this as a distinct disorder (Reference Alexopoulos and KellyAlexopoulos 2009a).

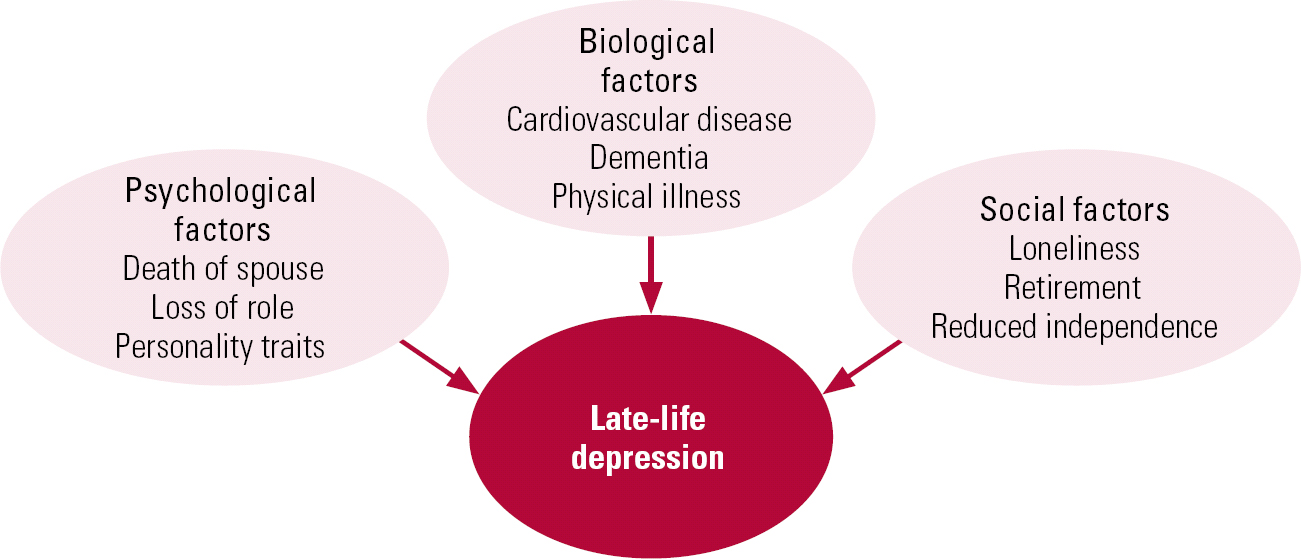

The aetiology of late-life depression is multi-factorial (Fig. 1) and includes biological (Reference Alexopoulos, Meyers and YoungAlexopoulos 1997), psychological (Reference Kivela, Luukinen and KoskiKivela 1998; Reference Steunenberg, Beekman and DeegSteunenberg 2007) and social factors (Reference Steptoe and MarmotSteptoe 2003; Reference Schwarzbach, Luppa and SikorskiSchwarzbach 2013).

FIG 1 Aetiology of late-life depression.

These risk factors can lead to relapse of depressive symptoms in those with an existing vulnerability, or first onset of the disorder in later life. Since many of the aetiological factors are age related, there has been (and continues to be) a misconception that depression in older people is inevitable given the frequency of physical ill health, bereavement and loss of role in this age group. This prejudice may affect help-seeking by patients and treatment offered by health professionals, and could be one reason why late-life depression remains an underrecognised and undertreated disorder, particularly among those living in nursing homes (Reference Brown, Lapane and LuisiBrown 2002). Given the significant adverse impact on patients, their families and carers, late-life depression warrants greater efforts at recognition and effective, evidence-based treatment.

Prescribing for older adults

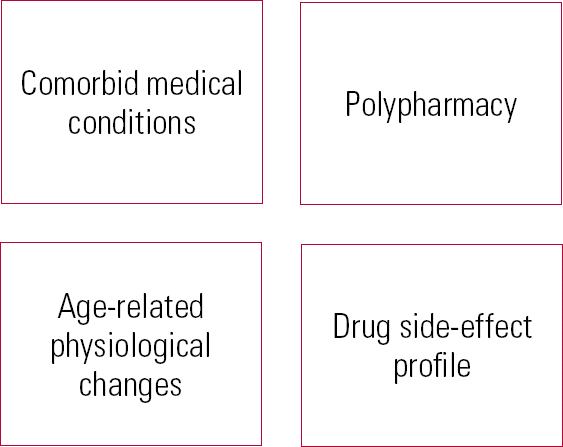

Pharmacotherapy can be used effectively for late-life depression (Reference Cipriani, Furukawa and SalantiCipriani 2009), but treatment requires a distinct approach because of age-related physiological changes, which alter pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Drug distribution within the body changes as a result of increased body fat and reduced volume of water. Hydrophobic compounds (e.g. antidepressants and antipsychotics) are therefore more readily distributed, whereas there is reduced distribution of hydrophilic compounds. Renal excretion is reduced, so there may be increased concentrations of active compounds that are renally excreted (Reference TurnheimTurnheim 2003). These changes mean that lower doses, slow titration and careful monitoring are needed (Reference Roose and SchatzbergRoose & Schatzberg 2005; Reference Nelson, Delucchi and SchneiderNelson 2008). The increased prevalence of comorbid medical conditions in this age group means that patients are more vulnerable to medication side-effects. Polypharmacy is a risk, and care is needed to minimise the effects of drug interactions (Reference Mark, Joish and HayMark 2011). These considerations should not discourage the use of pharmacological treatment of late-life depression, but they do necessitate a careful review of medical history before drug regimens are changed (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 Considerations before prescribing for older adults.

The evidence base

This article gives an overview of treatments for late-life depression (pharmacological, psychological and neurostimulation) based on a search of four databases (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and PubMed) for the terms [treatment or therapy] and [depression or depressive] and [old age or older or late-life or geriatric]. We have aimed to summarise important and recent research findings in a format that is clinically relevant.

Pharmacological treatment

Monotherapy

SSRIs: sertraline and citalopram

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most common first-line treatment for late-life depression, as is the case for younger patients. Sertraline has the best evidence for efficacy and tolerability, although there is also good evidence for escitalopram and citalopram in those over 65 (Reference Alexopoulos, Reynolds and BruceAlexopoulos 2009b; Reference Cipriani, Furukawa and SalantiCipriani 2009). All three have the advantage of a favourable side-effect profile and can be taken by people with a history of cognitive impairment and stroke (Reference AplerApler 2011).

Although citalopram was previously recommended for use in those with cardiovascular disease, recent data have highlighted the risk of prolonged QT interval with the drug, and the maximum recommended dose for older adults has now been reduced (Reference Waring, Graham and GrayWaring 2010; Reference Fayssoil, Issi and GuerbaaFayssoil 2011; Reference HowlandHowland 2011). Citalopram should not be prescribed in conjunction with other agents that prolong the QT interval, such as antipsychotics and certain antibiotics (e.g. erythromycin). It is not yet clear whether the effect on the QT interval is specific to citalopram, or whether it represents a side-effect across SSRIs more generally. Until more data are obtained to support or refute this, sertraline could be considered the best first-line SSRI option for the treatment of late-life depression on the basis of efficacy and tolerability (Reference Cipriani, La Ferla and FurukawaCipriani 2010).

It should be noted that some studies have cast doubt on the efficacy of SSRIs in late-life depression. For example, in two randomised, double-blind trials escitalopram did not show superior efficacy over placebo in treating depression in patients over 60 years of age (Reference Kasper, De Swart and Friis AndersenKasper 2005; Reference Bose, Li and GandhiBose 2008). A meta-analysis failed to find a significant difference between citalopram and other antidepressants (e.g. tricyclics or alternative SSRIs) in terms of depression remission (Reference Seitz, Gill and ConnSeitz 2010). There may also be clinical reasons to avoid use of SSRIs, for example in those with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding or on other medications that may precipitate this.

Mirtazapine

Where SSRIs are contraindicated, or poorly tolerated, other classes of antidepressant can be used as first-line treatment (Fig. 3). Mirtazapine is one alternative for first-line treatment in older adults (Reference Cipriani, Furukawa and SalantiCipriani 2009; Reference Watanabe, Omori and NakagawaWatanabe 2011). It has few cardiac side-effects and a weaker association with hyponatraemia (Reference Jung, Jun and KimJung 2011); in patients with insomnia and anorexia, its side-effects may be exploited for therapeutic benefit. It appears to have a faster onset of action than SSRIs, with beneficial effects found at 2 weeks (Reference Watanabe, Omori and NakagawaWatanabe 2011). It is worth noting that these studies supporting use of mirtazapine in older adults were not specific for this age group, but older patients were included in the analysis.

FIG 3 Monotherapy in late-life depression.

Tricyclics: nortriptyline

Tricyclic antidepressants are also effective treatments in older age groups. Nortriptyline shows efficacy and tolerability comparable to those of sertraline, with a response rate of 61% (95% CI 49%–73%) for patients on nortriptyline, compared with 72% (95% CI 61%–82%) for patients on sertraline (Reference Bondareff, Alpert and FriedhoffBondareff 2000). Adverse effects were similar in both groups, although those prescribed nortriptyline had a significant increase in specific symptoms, including dry mouth and constipation (Reference Bondareff, Alpert and FriedhoffBondareff 2000). Tricyclic antidepressants should be used with caution because of the risk of cardiac side-effects (e.g. prolongation of QT interval with amitriptyline) and toxicity in overdose, and because their antimuscarinic effects are more likely to exacerbate cognitive impairment.

Side-effects from all antidepressants are more common in older adults. A population-based study showed that rates of adverse effects were highest in the first 28 days after starting a prescription; SSRIs were associated with the highest risk of falls and hyponatraemia (Reference Coupland, Dhiman and MorrissCoupland 2011). Although Coupland et al did not find an increased risk of adverse events from tricyclic antidepressants (which would traditionally be associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity), given that their study was based on information from a prescribing register, it is likely that certain antidepressants would not have been prescribed to at-risk groups in clinical practice. This would have given rise to an important source of selection bias (Reference Coupland, Dhiman and MorrissCoupland 2011). For example, dosulepin and reboxetine are not recommended for use in older adults (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2009a,b).

Second-line agents: venlafaxine

Response to antidepressants can take at least 6 weeks. If there is only a modest improvement at this stage, the antidepressant should be continued for a further 4 weeks or, if tolerated, the dose should be increased (Reference RushRush 2007). Using this strategy, a large proportion of patients would be expected to respond or remit by 12 weeks (Reference RushRush 2007). Where first-line monotherapy has been ineffective, switching to a second-line agent (in the same or a different class) is a useful strategy, particularly for those who received minimal benefit or could not tolerate the first-choice antidepressant (Reference RushRush 2007).

Venlafaxine has been proposed as a useful second-line antidepressant (Reference Rush, Trivedi and WisniewskiRush 2006; Reference Lenox-Smith and JiangLenox-Smith 2008; Reference Cipriani, Furukawa and SalantiCipriani 2009). An open-label study demonstrated the efficacy of venlafaxine in older patients with an atypical subtype of depression, with symptoms of mood reactivity, hypersomnia and increased appetite (Reference Roose, Miyazaki and DevanandRoose 2004). Venlafaxine may, however, exacerbate hypertension and therefore close monitoring of this is needed at treatment initiation.

Combination and augmentation therapy

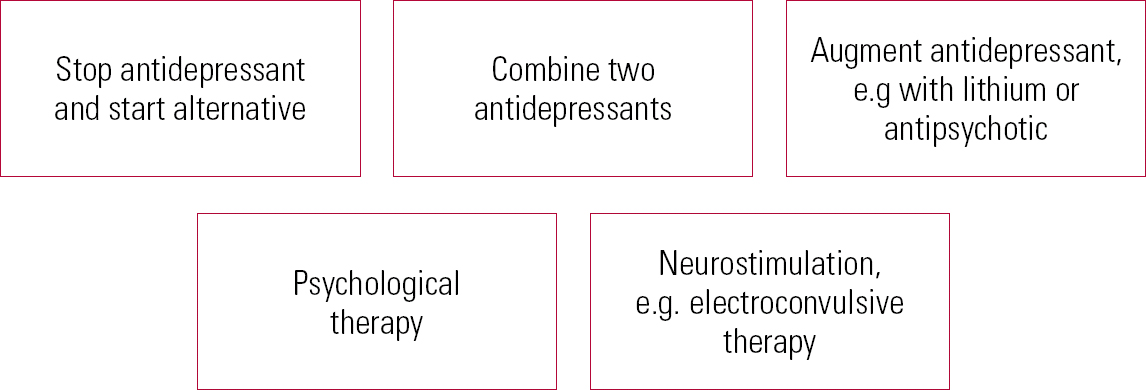

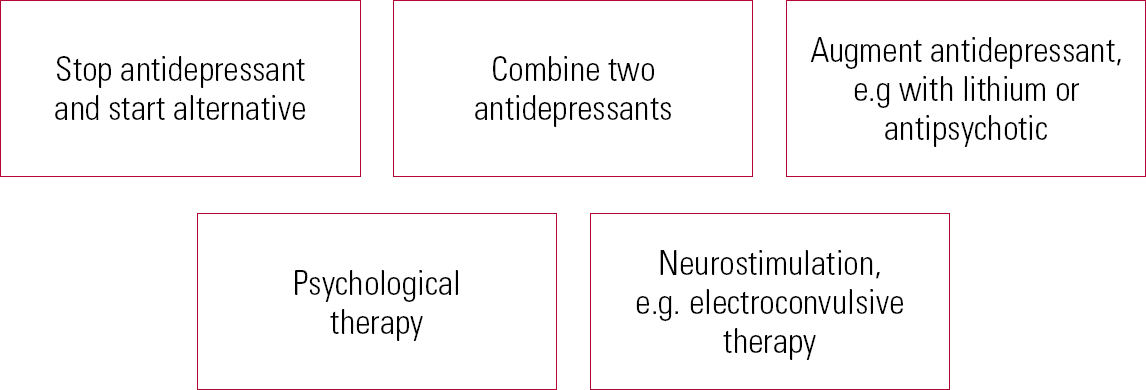

In practical terms, stopping one antidepressant and replacing it with an alternative can be difficult in someone who is severely ill. In such cases, the use of combination (two antidepressants) or augmentation (antidepressant plus another agent) strategies may be preferable (Fig. 4). Antidepressants with separate mechanisms of action can be combined for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (Reference Dodd, Horgan and MalhiDodd 2005). Combining an SSRI with venlafaxine provides more effective treatment compared with augmentation by psychological therapy (Reference Thase, Friedman and BiggsThase 2007). Combining mirtazapine with venlafaxine may be associated with increased side-effects, without significant therapeutic benefit (Reference Rush, Trivedi and StewartRush 2011).

FIG 4 Strategies for treating resistant depression.

There is evidence of the beneficial effects of augmentation strategies in depression, yet despite this, those who require augmentation show lower recovery rates and recover more slowly; comorbid medical conditions and symptoms of anxiety are associated with a poorer prognosis (Reference Dew, Whyte and LenzeDew 2007). As in younger populations, lithium can be used as an effective augmenting agent (Reference Dew, Whyte and LenzeDew 2007). For older adults, this should be accompanied by careful monitoring of renal function, using lower doses than in younger patients. Sodium valproate is not recommended as an augmenting agent in older adults (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2009a,b).

Antidepressants and antipsychotics

Augmentation of antidepressant treatment with antipsychotic medication is useful for those with severe depression, particularly where there are psychotic symptoms, providing there has been careful consideration of the risks and benefits (Reference AlexopoulosAlexopoulos 2011). For psychotic depression in older adults, treatment with olanzapine and sertraline has shown significantly higher remission rates than treatment with olanzapine alone (Reference Meyers, Flint and RothschildMeyers 2009). Olanzapine is associated with increased cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations, although the associated weight gain may be less significant in older people than in younger adults (Reference Meyers, Flint and RothschildMeyers 2009). In a randomised placebo-controlled study of older people with resistant depression, augmentation of citalopram with risperidone led to symptom resolution in a substantial number of participants, and a delay in time to relapse (56% in the risperidone group and 65% in the placebo group relapsed) (Reference Alexopoulos, Canuso and GharabawiAlexopoulos 2008). Although these results were non-significant, they add to evidence that suggests antipsychotics may be a clinically useful strategy, particularly for subgroups of patients with severe depression and psychotic symptoms.

In older adults, especially in those with a history of cardiovascular disease, antipsychotics should be used cautiously and with careful monitoring to minimise side-effects. Antipsychotics should be avoided if there are concerns that the individual has cognitive impairment, because of the increased risk of stroke associated with their use in that context (Reference Sacchetti, Trifiro and CaputiSacchetti 2008).

Cognitive impairment is a core feature of late-life depression, and this has resulted in the hypothesis that treating the cognitive symptoms could improve outcomes for the depression. One randomised double-blind trial compared antidepressant plus donepezil with antidepressant plus placebo in patients with late-life depression (Reference Reynolds, Butters and LopezReynolds 2011). The addition of donepezil resulted in no clear benefit in either preventing recurrence of depression or preventing the development of mild cognitive impairment or dementia.

Relapse prevention

There is good evidence that maintenance therapy in patients over 60 who have achieved remission is effective in preventing relapses and recurrences. Tricyclic antidepressants have comparable efficacy and both show good tolerability (Reference Kok, Heeren and NolenKok 2011). In patients over 70, depression was less likely to recur if they maintained antidepressant treatment with paroxetine for 2 years; monthly maintenance psychotherapy (interpersonal psychotherapy) did not prevent recurrence (Reference Reynolds, Dew and PollockReynolds 2006). Given the high risk of relapse in older patients (Reference Beekman, Geerlings and DeegBeekman 2002), pharmacotherapy should be continued for at least 2 years.

Psychological therapies

Informal psychotherapeutic approaches can increase the effectiveness of pharmacological therapy. One ‘treatment intervention programme’ (a brief, early intervention that provided psycho-education and support) in addition to pharmacotherapy led to improved outcomes for older adults, compared with pharmacotherapy alone (Reference Sirey, Bruce and AlexopoulosSirey 2005). In another study, the outcome of depression among older people living in residential homes was improved by better training of care staff and by providing residents with activity programmes and education about depression (Reference Llewellyn-Jones, Baikie and SmithersLlewellyn-Jones 1999). A package of supportive care may be particularly useful for people with mild depression or dysthymia (Reference Ciechanowski, Wagner and SchmalingCiechanowski 2004).

The evidence for use of formal psychological approaches to treat late-life depression is weak. A review of group psychotherapy for older adults with depression showed that interventions based on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) had modest efficacy over waiting-list controls, and that these benefits were maintained at follow-up (Reference Krishna, Jauhari and LeppingKrishna 2011). A Cochrane review of psychological therapies for older people with depression found that CBT was superior to active control interventions. However, as the studies were few and heterogeneous, the evidence overall is weak. There were no trials comparing psycho-dynamic psychotherapy with control conditions (Reference Wilson, Mottram and VassilasWilson 2008).

An early meta-analysis of 17 studies found that a range of psychosocial treatments for depression in older adults were reliably more effective than no treatment on self- and clinician-rated depression measures (Reference Scogin and McElreathScogin 1994). Although the evidence is weak, these may still represent an important treatment modality.

Modifications to psychotherapeutic techniques such as consideration of the context, the patients' generational group, their maturity and additional factors (e.g. physical illness and cognitive impairment) may help to improve efficacy when used with older adults (Reference KnightKnight 2009). Although there is limited evidence, psychological approaches to treatment on an individual level may be very useful for patients, and should therefore be considered when treating older patients with late-life depression.

There is limited evidence regarding the addition of psychological therapies to prevent relapse in older adults. In older patients with recurrent major depression, maintenance treatment with nortriptyline plus interpersonal therapy was superior to interpersonal therapy plus placebo in terms of relapse prevention, and showed a trend towards superior efficacy over nortriptyline monotherapy (Reference Reynolds, Frank and PerelReynolds 1999). On the contrary, in older patients who showed a partial response to escitalopram, there was no additional benefit from augmenting treatment with interpersonal therapy compared with depression care management (Reference Reynolds, Dew and MartireReynolds 2010).

Neurostimulation

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for depression in older people (Reference Tew, Mulsant and HaskettTew 1999). It is an option for patients who have not responded to pharmacological therapy, or for patients with depressive disorder who need rapid treatment owing to the risk of self-neglect or suicide (Reference Allan and EbmeierAllan 2011a).

The main risks of ECT are related to use of a general anaesthetic, so careful assessment of medical and anaesthetic risk is needed, with clinical examination and relevant physical investigations (e.g. electrocardiogram, venepuncture and chest X-ray) prior to first ECT, repeated at regular intervals as necessary. Another important consideration is the risk of cognitive side-effects, and cognition needs to be carefully monitored before and during ECT (Reference Kennedy, Milev and GiacobbeKennedy 2009).

Bilateral electrode placement acts more rapidly and is more effective than unilateral, but it is associated with greater cognitive side-effects (Reference Carney and GeddesCarney 2003). Therefore, in older patients who are at risk of cognitive impairment, unilateral placement is preferred initially, unless there are urgent clinical reasons which necessitate use of bilateral ECT. The efficacy of ECT is substantially increased by the addition of an antidepressant medication (Reference Sackeim, Dillingham and PrudicSackeim 2009).

Electroconvulsive therapy can be administered on an out-patient basis, provided that the patients are effectively supervised, particularly in the 24 hours following treatment. This is a useful treatment option for patients with severe depression who prefer to avoid hospital admission. Continuation ECT (where the interval between treatments is gradually increased) can reduce the number of admissions and shorten their duration for older people with severe depressive disorder (Reference O'Connor, Gardner and PresnellO'Connor 2010).

Alternatives to ECT

Alternative neurostimulation therapies that do not require an anaesthetic may be beneficial for patients with a range of comorbid medical conditions, although there is little research specifically on older adults. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), though not widely used in clinical practice at present, shows promise as a treatment of depression (Reference Allan, Herrmann and EbmeierAllan 2011b, Reference Allan, Kalu and Sexton2012). Transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) also appears to have good antidepressant efficacy (Reference Allan, Kalu and SextonAllan 2012; Reference Kalu, Sexton and LooKalu 2012; Reference Loo, Alonzo and MartinLoo 2012). Both treatments have the benefit of fewer side-effects and no significant effects on cognition. They will require further evaluation, including trials in older patients, before routine use becomes widespread.

Depression and dementia

Depression is found in up to 20% of people with dementia (Reference Nelson and DevanandNelson 2011), and is underdiagnosed and undertreated in nursing home residents with cognitive impairment (Reference Volicer, Frijters and Van der SteenVolicer 2012). Diagnosing depression in those with cognitive impairment can be challenging, as presenting symptoms may be subtle behavioural change, sleep disturbance and reduced appetite.

Unfortunately, there is limited evidence for use of antidepressants in this patient group (Reference Bains, Birks and DeningBains 2002). A meta-analysis of antidepressant treatment of people with depression and dementia showed limited efficacy; there was significant heterogeneity between studies and many were underpowered to detect differences, leading to inconclusive findings (Reference Nelson and DevanandNelson 2011).

One of the first large studies of sertraline for the treatment of moderate depressive disorder in people with cognitive impairment showed a favourable effect (Reference Weintraub, Rosenberg and DryeWeintraub 2010), yet follow-up studies have failed to replicate this (Reference Rosenberg, Drye and MartinRosenberg 2010). One of the largest studies in this field included over 300 patients with Alzheimer's dementia and depression, who were randomised to receive placebo, mirtazapine or sertraline; there were no significant differences between groups in terms of depression scores following treatment (Reference Banerjee, Hellier and DeweyBanerjee 2011). This was an important clinical finding, suggesting that antidepressants may not be a good first-line treatment for patients with depression who also have dementia. However, this study did not include patients with suicidal thoughts, and it may be that those with severe depression and suicidal ideation would have a different pattern of response to antidepressant medication.

The lack of efficacy of antidepressants in those with dementia raises the interesting question of whether the pathophysiological mechanisms for developing depression differ in people with and without dementia. If this is the case, it could explain why antidepressants show reduced efficacy.

Although the formal evidence for efficacy of antidepressants in people with dementia is weak, it might be worthwhile trying them on individual patients in clinical practice even if there is coexisting cognitive impairment. In addition, clinicians should also focus on non-pharmacological treatments of depression such as CBT, problem-solving therapy and reminiscence therapy, which can be used to target mood as well as cognitive symptoms (Reference Wilkins, Kiosses and RavdinWilkins 2010). The use of behavioural treatments, including exercise, shows beneficial outcomes for depressed patients and their carers (Reference Teri, Logsdon and UomotoTeri 1997, Reference Teri, Gibbons and McCurry2003).

Finally, it is important to note that depressive presentations can mimic cognitive impairment, so care must be taken to avoid diagnosing dementia in someone who has a treatable depressive illness. Clinicians should also be alert to the difficulties of differentiating subcortical vascular disease from depression; a history of treatment-resistant depression should prompt the use of neuroimaging to investigate vascular pathology such as lacunar infarcts. Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred option for this, but vascular changes may also be visible on computed tomography (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2006). Treatment approaches for subcortical vascular disease involve use of a strict behavioural approach and a highly structured daily routine.

Conclusions

Late-life depression is a common disorder, which is underrecognised and undertreated (Box 1). It is associated with high morbidity and mortality and therefore needs to be correctly diagnosed and appropriately treated. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are a good first-line strategy, with particularly strong evidence for sertraline in terms of efficacy and tolerability (Reference Cipriani, Furukawa and SalantiCipriani 2009). It is important to continue first-line treatment for a sufficient duration (at least 6 weeks), before increasing the dose or adding a second antidepressant, if needed (Reference RushRush 2007). Antipsychotic medication and lithium are good options for augmentation. Given the paucity of evidence for psychological therapies, combination or augmentation with pharmacological agents is likely to be more clinically effective than the addition of a psychological intervention. However, for those who are psychologically minded, these may be useful strategies.

BOX 1 Clinical summary

-

• Recognise late-life depression as a treatable illness

-

• Pay careful attention to medical and medication history

-

• Use a systematic approach to treatment

-

• Continue antidepressants for 2 years to prevent relapse

-

• Adopt a holistic approach to care, including psychological and social support

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 What percentage of older people living in institutions have depression?

-

a 5%

-

b 10%

-

c 20%

-

d 25%

-

e 30%.

-

-

2 The SSRI with the best evidence for efficacy and effectiveness in late-life depression is:

-

a citalopram

-

b escitalopram

-

c sertraline

-

d fluoxetine

-

e paroxetine.

-

-

3 Olanzapine can be used where clinical benefits outweigh the risks; preferably, it is used to augment antidepressants in patients with:

-

a no significant medical history

-

b diabetes

-

c heart disease

-

d history of stroke

-

e cognitive impairment.

-

-

4 To prevent relapse, pharmacotherapy should be continued for:

-

a 3 months

-

b 6 months

-

c 1 year

-

d 2 years

-

e indefinitely.

-

-

5 In what proportion of people is depression comorbid with dementia?

-

a 10%

-

b 20%

-

c 30%

-

d 40%

-

e 50%.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | c | 3 | a | 4 | d | 5 | b |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.