Solution-focused brief therapy is an approach to psychotherapy based on solution-building rather than problem-solving. It explores current resources and future hopes rather than present problems and past causes and typically involves only three to five sessions. It has great value as a preliminary and often sufficient intervention and can be used safely as an adjunct to other treatments. Developed at the Brief Family Therapy Center, Milwaukee (Reference Berg, Berg and Lipchikde Shazer et al, 1986), it originated in an interest in the inconsistencies to be found in problem behaviour. From this came the central notion of ‘exceptions’: however serious, fixed or chronic the problem there are always exceptions and these exceptions contain the seeds of the client's own solution. The founders of the Milwaukee team, de Shazer (1988, 1994) and Berg (Reference BergBerg, 1991; Reference Berg and MillerBerg & Miller, 1992), were also interested in determining the goals of therapy so that they and their clients would know when it was time to end! They found that the clearer a client was about his or her goals the more likely it was that they were achieved. Finding ways to elicit and describe future goals has since become a pillar of solution-focused brief therapy.

Since its origins in the mid-1980s, solution-focused brief therapy has proved to be an effective intervention across the whole range of problem presentations. Early studies (Reference Bergde Shazer, 1988; Reference Miller, Hubble and DuncanMiller et al, 1996) show similar outcomes irrespective of the presenting problem. In the UK alone, Lethem (1994) has written on her work with women and children, Hawkes et al (1998) and MacDonald (1994, 1997) on adult mental health, Rhodes & Ajmal (1995) on work in schools, Jacob (2001) on eating disorders, O'Connell (1998) on counselling and Sharry (2001) on group work.

My colleagues and I at the Brief Therapy Practice in London work routinely with all age groups and problems, including behavioural problems at school, child abuse and family breakdown, homelessness, drug use, relationship problems and the more intractable psychiatric problems. With the latter there is no claim being made that the cure for schizophrenia or any other psychiatric condition has been found, but if a woman with schizophrenia has the wish to get back to work or one with depression wants to enjoy caring for her children then there is a good chance that these goals will be realised and, in many cases, maintained. In brief, it is a simple all-purpose approach with a growing evidence base to its claim to efficacy.

The therapeutic process

As the practice of solution-focused brief therapy has developed, the ‘problem’ has come to play a lesser and lesser part in the interviewing process (Reference George, Iveson and RatnerGeorge et al, 1999), to the extent that it might not even be known. Instead, all attention is given to developing a picture of the ‘solution’ and discovering the resources to achieve it. A typical first session involves four areas of exploration (Box 1).

Box 1 Four key tasks for a typical first session

| Task of therapist | Examples of opening questions |

|---|---|

| Find out what the person is hoping to achieve from the meeting or the work together | What are your best hopes of our work together? How will you know if this is useful? |

| Find out what the small, mundane and everyday details of the person's life would be like if these hopes were realised | If tonight while you were asleep a miracle happened and it resolved all the problems that bring you here what would you be noticing different tomorrow? |

| Find out what the person is already doing or has done in the past that might contribute to these hopes being realised | Tell me about the times the problem does not happen When are the times that bits of the miracle already occur? |

| Find out what might be different if the person made one very small step towards realising these hopes | What would your partner/doctor/colleague notice if you moved another 5% towards the life you would like to be leading? |

The earlier emphasis on exploring exceptions to the problem has been replaced by an interest in what the client is already doing that might help achieve the solution. This has led to a new assumption that all clients are motivated. Initially, the issue of motivation was dealt with by a classification system (customer, complainant and visitor) similar to that used in motivational interviewing (Reference Miller and RollnickMiller & Rollnick, 1991), depending on the client's attitude to the problem. The emphasis on the preferred future has made the client's view of the problem redundant to the therapy. All that clients need is to want something different – even if at the starting point they do not think that something different is possible.

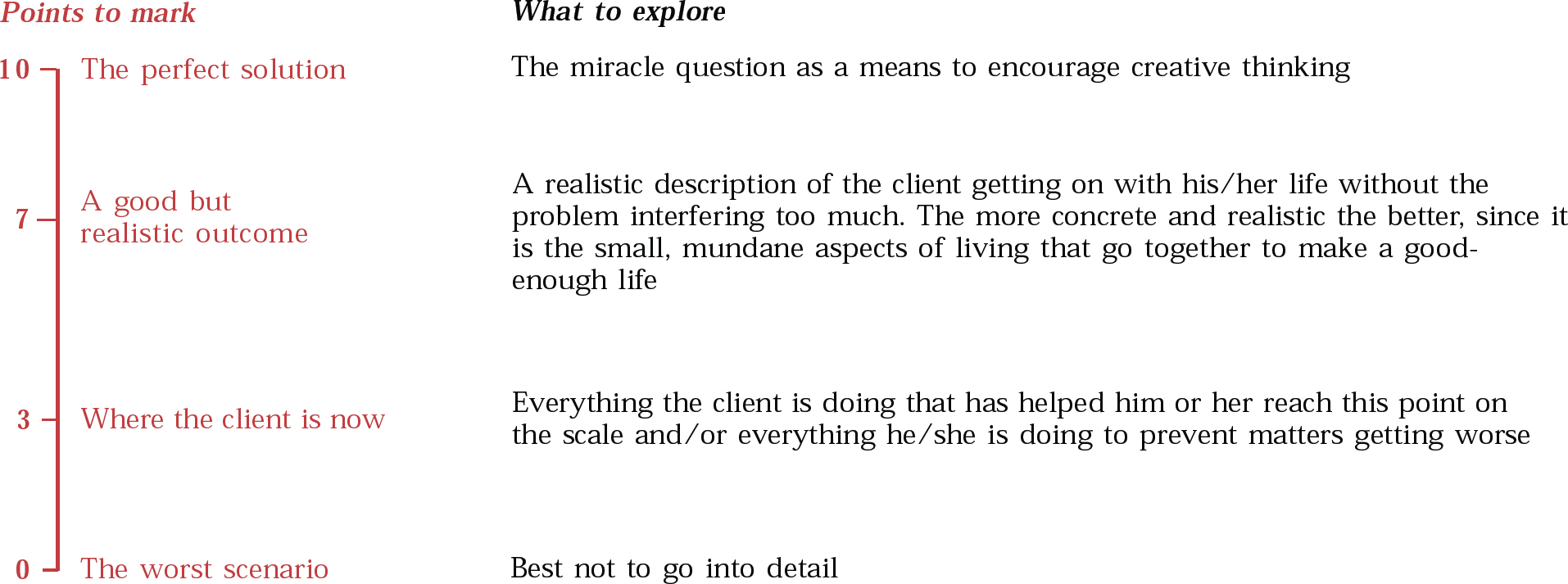

Scales

One of the most useful frameworks for a solution-focused interview is the 0 to 10 scale, where 10 equals the achievement of all goals and zero is the worst possible scenario. The client is asked to identify his or her current position and the point of sufficient satisfaction. Within this framework it is possible to define ultimate objectives, what the client is already doing to achieve them and what the next step might be (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The scale framework

The scale framework can be used to differentiate different aspects of the problem and its solution. For example, a person with depression might feel devalued by colleagues. Each of these aspects might be explored through separate scales. Similarly, when the client is experiencing multiple problems, each problem can be addressed with its own scale. Where several scales are used, areas of overlap soon become apparent, which helps the client realise that movement in one area can lead to improvements in others.

Coping and compliments

Looking for the client's strengths and resources and commenting on them is an important part of a solution-focused therapy session.

Sometimes clients’ lives are so difficult that they cannot imagine things being different and cannot see anything of value in their present circumstances. One way forward is to be curious about how they cope – how they manage to hang on despite adversity. In one case, a therapist was asked to see Gary, a long-term in-patient at high risk of suicide. Gary could see no future, nothing of value in his present, was not going to cope any longer and was going to end it all. The therapist wondered at the courage and perseverance that had led Gary to endure 2 years of ‘hell’ and asked about his previous life. It was full of ordinary achievements and successfully met responsibilities, which the therapist suggested might have given him the strength to handle his current crisis. He agreed but thought he was running out of resources. When the therapist asked him to describe how he would know that he had just sufficient resources left to see him ‘round the corner’ Gary said he would try electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) again. Recognising the extent of the client's problem and complimenting him on his courage and perseverance were the key interventions in this case. Hospital staff recognised this and when Gary agreed to a further course of ECT they supplemented the treatment by seeking opportunities to compliment him. He was discharged 3 months later.

Subsequent sessions

On average, solution-focused brief therapy takes about five sessions, each of which need be no more than 45 minutes long. It rarely extends beyond eight sessions and often only one session is sufficient. If there is no improvement at all after three sessions, it is unlikely to work (although the three sessions are likely to provide most of the information required for a more traditional assessment). If possible, the time between sessions is lengthened as progress occurs, so a four-session therapy might extend across several months.

As it is the therapist's task to help the patient achieve a more satisfying life, follow-up sessions will usually begin by asking, ‘What is better?’ If there have been improvements, even for only a short time, they will be thoroughly explored: what was different, who noticed, how it happened, what strengths and resources the patient drew on in order to effect the change and what would be the next small sign of the change continuing. Scaling questions provide the simplest framework for these explorations.

If the situation has deteriorated, the therapist will be interested in how the patient coped and hung on through the difficulties and what he or she did to stop the situation deteriorating further. It often turns out that there have been considerable improvements that the patient had not noticed, having been too preoccupied with the problem to notice the inroads being made. In one case, a woman reported that her situation had worsened: not only did she still have her eating disorder but she was now having difficulties with her husband. In the process of looking at how she coped despite these increased difficulties it turned out that she had reduced her vomiting from several times a day to several times a week and that her arguments with her husband were a product of her more assertive position in the family. She went on to overcome the eating problem and establish a relationship with her husband that suited them both.

Summary

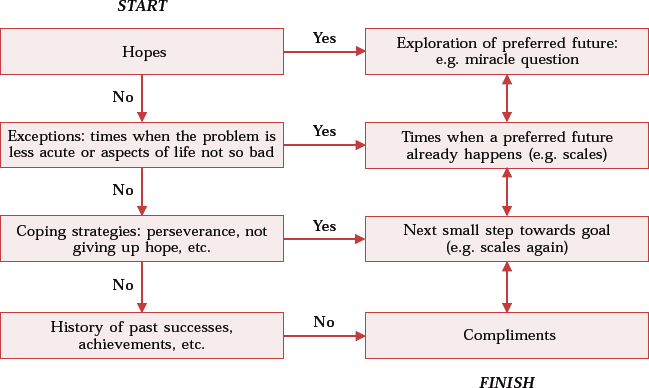

The difficult part of solution-focused brief therapy is developing the same fluency in asking about hopes and achievements as most of us have when asking about problems and causes. But the guiding framework is extremely simple, as Fig. 2 shows. Most first sessions will start at the top left of this flowchart and then move down through the right-hand column. However the session goes, it will end with compliments. Subsequent sessions are likely to concentrate on the second and third boxes in each column: more to the left if progress is slight and more to the right if things are progressing well. In all sessions attention is paid to the overall goal and each session ends with compliments relevant to the achievement of that goal.

Fig. 2 The ‘flow’ of a session

Case example 1: Exceptions to the problem of agoraphobia

Mrs Brown was agoraphobic and was seen at home. It is unusual for agoraphobic patients not to go out at all (children have to be taken to school, dogs walked, shopping done) but it seemed that Mrs Brown's case was so severe she had not stepped out of her front door for several months. Indeed, as the therapist's fruitless search for exceptions progressed, the problem description became ever more concerning. It turned out that Mrs Brown could not even bring her milk in off the step because being near the front door could set off a panic attack. The therapist had noticed that the stairs came down right beside the front door and after listening very seriously to Mrs Brown's worries, asked about the courage that it must take her to come down stairs each day. When she realised this was an absolutely serious question the tenor of the interview began to change. She said it was true that coming downstairs was difficult for her, because she had to pass the front door, but it ‘just had to be done’. As the conversation progressed it turned out that Mrs Brown sometimes sat quivering at the top of the stairs but so far had forced herself to come down because she could not bear the consequences of giving in to this aspect of her fear.

The more her daily courage was explored and acknowledged the stronger became her voice. She then began to remember other acts of courage, like saying to herself the day before ‘Don't be silly’ and bringing in the milk or some months earlier when she had made herself attend her aunt's funeral because her aunt had loved her. As she became aware of this hidden but persistent courage, Mrs Brown began to put it to greater use and over the following weeks, with two more clinic sessions to support her, she made her way back into the outside world.

Case example 2: A future without eating problems

Mrs Black had suffered from an eating disorder for 12 years. She alternated between self-starvation and binge eating, although since her late teens had kept reasonably good control of the extremes. But she was becoming tired, despondent and depressed. Most of the first interview she spent answering questions about how her ordinary everyday life as a young mother, wife and woman might be different if the eating problem were resolved. She described the difference it would make to her thoughts, feelings and actions from the moment of waking. She described not only what she herself would notice different but also what family and friends would notice. By the fourth and final session she had been eating normally for several weeks.

In a subsequent interview with another professional about the process of therapy she said that she had know by the end of the first session that she would resolve her problem. Until then she had not seen a way forward so had assumed that there was none. The painstaking process of her answers and the description they had given of an alternative way of living had charted out a path which she knew she could take. Two years later the referring professional reported that Mrs Black was still eating normally.

Case example 3: A reluctant client

What follows are sections of transcript from a single-session therapy with John, a 35-year-old ‘street drinker’ with a prison record and currently subject to a probation order requiring him to attend an alcohol rehabilitation centre. The therapist is visiting the centre and will only see John once. The transcript is intended to show the ‘small print’ of a session – how the way the questions are asked and their closeness to the client's answers leads to the uncovering of an underlying but so far hidden motivation.

Therapist So John, what are your hopes for this session?

John I don't know.

Therapist What do you think?

John I suppose it will be useful.

Therapist In what way do you hope it will be useful?

John I don't know.

Therapist What do you think?

John Stop me drinking.

Therapist So if this meeting helps you stop drinking it will have been worth your while?

John Yes.

Therapist So can I ask you some unusual questions?

John Sure – I've seen so many doctors and people, I'm used to it!

Therapist Okay, here's an unusual one – let's imagine that tonight while you're asleep a miracle happens and your drink problem is resolved. But because you're asleep you don't know. What will you notice different in the morning that begins to tell you that drink is no longer an issue for you?

John I don't know, I can't imagine that.

Therapist Have a go!

John I don't believe in miracles.

Therapist No, neither do I but it's very helpful for me to have an idea about how you want your life to be so we can move in the right direction. So what time would you be waking up?

John About nine.

Therapist And what's the first thing you'll notice yourself doing differently that begins to tell you a miracle has happened?

John Nothing will be different – I'll get up, take some stuff to clear my head, have a coffee and go out.

Therapist Stuff?

John I'll take anything, anything I can get hold of, pills, the lot. It helps clear the head.

Therapist So let's say the miracle stops you needing stuff as well as drink. What will be different when you go out?

John Look, what you have to realise is that 90% of my friends drink, so what do you expect me to do?

Therapist No, it's certainly not easy – so what might you do if drink and drugs are no longer a problem?

John I don't know, there's all sorts of things.

Therapist So what might one of them be?

John [with a resigned sigh] Okay, the library, maybe I'd go to the library and look at the papers.

Solution-focused brief therapy, like all other talking therapies, relies on the creative power of the spoken word. John is beginning to describe what he thinks is an unlikely future, yet it is one that fits at least one aspect of his hopes and so far it contains nothing unrealistic. The more clearly it is described the more possible it will become. The idea of a ‘miracle’ to achieve the goal of the therapy proves a useful way to bypass some of the psychological blocks to thinking about a different future.

The session continues by drawing out, question by question, what would be different about his day if he went to the library. As his description progresses John becomes patently more interested in his account. Each time a possible block arises the therapist invokes the ‘miracle’, not to remove the block but to ask how John would deal with it if drink and drugs were no longer a problem:

John The thing is, it's impossible to concentrate on anything because I'm always worrying about money.

Therapist So what would you notice about the way you worried about money if drink and drugs were no longer a problem?

John Well, then I'd have to do something about it, wouldn't I?

Therapist So what might you be thinking of doing?

John Well, I can get work if I need it – I do gardens.

The therapist makes no attempt to advise or encourage John to ‘perform’ any of his described activities and simply ends the session by complimenting John on his honesty, his continuing interest in fighting his problem, his loyalty to his drinking friends and his courage in continuing to live such a hard life.

The Centre staff who had known John for a number of years reported a major shift in John's attitude after this session. He began to cooperate with the treatment programme and, although it took another year, he was eventually discharged. At follow-up a further year later he was working, still finding life hard but no longer using drugs or drink as a way of dealing with his difficulties.

Case example 4: Using scales to score a ‘historic goal’

Adam was one of many young people in difficulty at school seen by my colleagues and I. He had been excluded temporarily on several occasions, moved to a ‘cooling off’ unit, and been given one last chance. Adam said he did not want to be excluded, mainly because it would upset his mother, but he hated school and described all the teachers as picking on him. In the second session he could only report one change for the better: in football.

The therapist decided to try following this track (Reference SelekmanSelekman, 1993) and asked Adam to rate his football abilities on a 0–10 scale compared with all his friends. He put himself at 9. The next 30 minutes were spent exploring in great detail what it took to become that skilled at football. At first Adam said ‘because I like it’, but as the conversation progressed many more significant factors began to show: practice, perseverance, teamwork, humour, quick thinking, decision-making, fitness, reliability, loyalty, accepting discipline and self-discipline all turned out to be important components, even though Adam had been largely unaware of them until this interview. Another scale was then drawn in relation to school, with 10 being no problems and 0 being permanent exclusion. He put himself at 2. The therapist asked Adam which of his football skills had been most helpful to him in avoiding permanent exclusion so far. He said he always turned up for school (as he did for football practice), he sometimes did as the teachers told him (accepting discipline) and occasionally he worked (because he ‘decided’ to). Finally, the therapist asked him which other football skills he would find himself using if he moved from 2 to 3 on his scale. He thought and picked self-discipline, the quality he had been most proud to discover in his football scale.

By the fifth and final meeting with Adam he was doing well across all his classes, including history, which he thought he would never work in because it was so boring. When asked how he did it, Adam said it was self-discipline and the realisation that it was less boring to work than to mess about.

Single-session therapies

All therapists from Freud to the present have ‘single-session successes’, but by and large these are seen as flukes. O'Hanlon (Reference O'Hanlon and WilkO'Hanlon & Wilk, 1986) learned much about brief therapy by interviewing therapists about such successes and identifying common factors, one of which was a focus on the future. Talmon (1993) and Hoyt (1984) identify and describe many of the characteristics of the single-session case. In solution-focused brief therapy, single-session transformations are common enough not to be a surprise. There are three possible explanations for this.

First, some clients are stuck in the problem mainly because they do not know the way out. The detailed description of a preferred future that normally characterises the first session becomes a sufficiently clear pathway for them to move off down it. Although there were three follow-up sessions in the case of Mrs Black (example 2 above), she had overcome the eating side of her difficulties by the second: the rest were focused on her dealing with the repercussion of the change on her everyday relationships (for a single-session eating disorder case description see Reference George, Iveson and RatnerGeorge et al, 1999: Ch. 5).

Second, some clients have already solved their problem but have not yet realised this. When they describe their preferred future they see that enough of it is already happening for them to continue without further therapy.

Third, in the process of reviewing their circumstances, measuring their hopes against their knowledge of reality and taking stock of what they already have, some clients come to a realisation that their lives, although not perfect, are perfectly manageable.

The following case examples describe two successful single-session interventions.

Case example 5: Being quiet

Ossie was 5 years old and on the verge of permanent exclusion from school because of ‘out-of-control’ and aggressive behaviour. He came from a large family and his mother was seriously disabled by multiple sclerosis, which was in a state of rapid advancement. Grandparents were helping out but there was major friction between family members and between the family and the multi-professional network. A ‘full assessment’ of Ossie had concluded that he was developmentally at a pre-nursery stage and so was unable to comprehend what was required of him at school, let alone do any of it. The brief therapy meeting was a last-ditch attempt to retrieve the situation and although it was attended by Ossie's mother, his teacher, the special needs teacher and his grandfather it was clear that no one had much hope of a good outcome.

In a session with more than one person the task of the therapist is to offer each participant a chance to describe his or her version of a preferred future and to explore what might be potential contributors to its realisation. In essence, the meeting is like a series of short, interwoven individual sessions.

Ossie was engaged in a few minutes of ‘problem-free talk’, then each person was invited to declare his or her hopes (all related to Ossie's behaviour at school) and then scales were used to mark Ossie's (very limited) progress towards the goal of good behaviour. For Ossie it was important to find a ‘language’ that he could use. Contrary to the assessment results, Ossie had both a complete grasp of school routines and regulations and a wish to work hard and stay out of trouble. He was invited to describe a good day at school by demonstrating sitting quietly, lining up quietly and walking in a line quietly. Everyone was asked to join in this demonstration, in which Ossie showed not only how he wanted to be but also his ability to be it.

As the meeting developed, teachers and family began to report many hitherto unnoticed signs of progress and by the end hope for Ossie's future had been rekindled. The fact that Ossie knew much more than had been apparent before the meeting goes a long way to explain his rapid advancement from an ‘impossible’ to a ‘good’ pupil.

Case example 6: Remembering tomorrow

Don had been advised to seek residential care for Brenda, his wife who had Alzheimer's disease. The referral for therapy was because he would not take this advice. Both he and Brenda said that their lives would be much more manageable if Brenda could remember more. The ‘miracle’ they were invited to explore was not the full return of Brenda's memory but her ability to make the fullest use of the memory power she still possessed. Step by step, Brenda managed to remember and describe everything that she had planned for the next day: this included doing her Christmas shopping with her daughter, the time her daughter would call and the effect on her daughter when she found that her mother not only remembered she was coming but also remembered who she was buying presents for and which shops she wanted to visit. In similar detail Don described what he would see different about his wife and the effect this would have on him and on their lives together.

Don and Brenda both became interested in the idea of remembering recent occasions when Brenda's memory seemed to work. They said that it was very refreshing to discover that all was not lost.

Two weeks later the couple returned, not for more therapy but just to let the therapist know that they did not think they needed any more sessions. They were in very high spirits and laughing when they said that they had thought long and hard but still could not work out if Brenda's memory had improved or it was simply not a bother to them any more. Whatever the reason, it was no longer a problem. Some years later their daughter contacted the therapist to say that her father had died but how grateful she and her parents had been for the session that ‘had given them back their marriage’.

In both of these single-session examples, as in many others, the improvements lasted over at least 2 years of follow-up. They were also situations in which it would have been impossible to predict that one session would be sufficient. There is no evidence that solution-focused brief therapists are unique in producing such outcomes but they are probably more open to them since their expectations are not restricted by diagnostic formulations.

A complementary treatment

Although solution-focused brief therapy is a treatment in its own right it can also be used to complement other treatments. In the cases of Gary and John above, both were seen as part of a much wider complex of treatments. The best that can be said is that the solution-focused brief therapy sessions helped each client to orient himself more effectively to the treatments that eventually worked.

One area of work in the clinic in which I practice is dealing with family breakdown. A family might be attending an intensive residential treatment centre and use occasional solution-focused brief therapy sessions to assist the working of the treatment plan. A first meeting might explore the question, ‘If this stay in the centre was to be 100% successful what would be different on the day after your discharge?’ or, ‘If this placement turns out to be just what you need, how will the staff know that it is working?’ Questions such as these help construct the signposts of success while allowing the main treatment to do the work. In a similar way general practitioners can use questions such as the following to orient their patients towards the signs of improvement and cure rather than just focusing on symptoms, which can have the effect of amplifying them:

-

• If these antidepressants work, how will you know? What will be the first sign that your mood is lifting?

-

• It sounds as though you have had a terrible time – what do you think has enabled you to cope with such courage?

-

• If we were to begin reducing your medication what do you think will tell us we are going at the right pace?

These are all questions that invite the patient to contribute his or her own expertise to the overall treatment programme in a way that is most likely to complement the primary treatment. The same is true in physical medicine, for instance, oncology, where the patient's attitude is likely to have an effect on treatment efficacy and outcome.

Conclusion

The complementary nature of solution-focused brief therapy is in part a product of its location outside conventional ‘scientific’ knowledge. In science, words are used to describe and delineate ‘reality’ and for something to be regarded as ‘real’ it must be possible to replicate it. The theoretical underpinnings of solution-focused brief therapy are to be found more within the realms of philosophy. It is based on an understanding of language and dialogue as creative processes. Because the central focus is on the future and because there is no framework for ‘understanding’ problems, there is little for patient and therapist (or therapist and therapist!) to disagree over.

However, the lack of a diagnostic structure in solution-focused brief therapy creates problems for the measurement of its efficacy. Most studies rely on client or referrer report and have little objective validity. However, a study on the treatment of recidivists after prison discharge (Reference Lindforss and MagnussonLindforss & Magnusson, 1997) has shown significant effectiveness. A major international research initiative, using accepted ‘scientific’ measures as well as new, more solution-focused measures, is currently being coordinated on behalf of the European Brief Therapy Association (http://www.EBTA2001.com) by Alasdair MacDonald. If this supports the findings of earlier studies then solution-focused brief therapy will have a significant part to play among the many treatment possibilities afforded by modern psychiatry.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Solution-focused brief therapy is based on:

-

a clear diagnostic formulations

-

b appreciating the client's resources

-

c detailed description of the client's problem

-

d the scientific study of personality

-

e the use of language as a creative process.

-

-

2. Solution-focused techniques involve:

-

a the ‘miracle’ question

-

b paradoxical injunctions

-

c complimenting the client

-

d careful administration of medication

-

e the patient's acceptance of the problem.

-

-

3. Solution-focused brief therapy has been effective in the treatment of:

-

a drug and alcohol misuse

-

b agoraphobia

-

c adolescent behavioural problems

-

d eating disorders

-

e chicken pox.

-

-

4. Solution-focused authors include:

-

a de Shazer

-

b Lethem

-

c Rollnick

-

d O'Hanlon

-

e White.

-

-

5. Scaling questions are used to explore:

-

a the patient's achievements

-

b the patient's description of the symptoms

-

c medication requirements

-

d possible areas for progress

-

e goals of therapy.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | T | a | T | a | T |

| b | T | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | F | c | F |

| d | F | d | F | d | T | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.