Reference Maris, Maris, Berman and MaltsbergerMaris (1992) describes suicide as a ‘multidimensional malaise in a needful individual who defines an issue for which the suicide is perceived as the best solution’, stating that as many as 85–90% of those who make suicide attempts never complete a suicide. It has been well documented that professionals cannot accurately predict suicide, a situation first highlighted by Reference RosenRosen (1954). This may be related to the low incidence of completed suicide, given the prevalence of suicidal thoughts, and the large numbers of false positives that are predicted when using conventional risk factors. There are challenges in designing, implementing and evaluating suicide prevention strategies (Reference WindfuhrWindfuhr 2009). The large numbers that would be required to conduct a study to predict suicide are daunting. Reference Gunnell and FrankelGunnel & Frankel (1994) calculated that to demonstrate a 15% reduction in suicide attempts, a sample of 45 000 people would be required. The challenges and rewards of this area of research are highlighted very well by Jobes and colleagues in the International Handbook of Suicide Prevention (Reference Jobes, Comtois, Brenner, O'Connor, Platt and GordonJobes 2011).

In preparing this article we carried out a literature search on MEDLINE, PubMed and Google Scholar. The key words used in the search were ‘suicide’, ‘suicide assessment’ and ‘suicide prevention’.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, 1 million people die from suicide every year. A decade ago, the World Health Organization (2002) recorded a 60% increase globally over a 45-year period. In 2011, there were 6045 suicides among people aged 15 and over in the UK, compared with 1901 deaths from road traffic accidents. The suicide rate was highest for middle-aged men (those in the 30- to 44-year-old and 45- to 59-year-old age groups). In particular, the rate among men aged 45 to 59 has increased significantly in the past 5 years (Department for Transport 2012; Office for National Statistics 2013). Retrospective psychological autopsy studies have found that 90% of completed suicides were associated with psychiatric disorders (Reference Barraclough, Bunch and NelsonBarraclough 1974; Reference Cavanagh, Carson and SharpeCavanagh 2003).

Suicidal ideation might be defined as ‘any self-reported thoughts of engaging in suicidal behavior’ (Reference O'Carroll, Berman and MarisO'Carroll 1996). Prevalence varies in different populations. For example, the Outcome of Depression International Network (ODIN) study, carried out in five countries within the European Union, found the prevalence of suicidal ideation in the general population to vary between 1.1% and 19% (Reference Casey, Dunn and KellyCasey 2008).

Suicide risk assessment

In the 1960s, suicide assessment scales placed more emphasis on prevention than on prediction. Reference Bouch and MarshallBouch & Marshall (2003, Reference Bouch and Marshall2005) outline three broad approaches to suicide assessment: the clinical, the actuarial and structured professional judgement (Box 1).

BOX 1 Summary of risk assessment approaches

-

• Clinical approach: relies on evidence-based professional opinion, an inadequate sole predictor of suicide.

-

• Actuarial approach: algorithm-based assessments produce a formal risk classification expressed by numerical values of probability and mostly using static and stable risk factors. The limited flexibility is a barrier to identifying a patient in immediate crisis.

-

• Structured professional judgement: a combination of individual patient assessment and evidence-based risk factors. The assessment is multidisciplinary and mainly used in forensic settings.

(Reference Bouch and MarshallBouch 2003, Reference Bouch and Marshall2005)

The transition from suicidal ideation to making a suicide attempt is a highly complex issue and we still do not fully understand how an individual progresses from mild suicidal thoughts associated with low mood and depression to serious ideation and plan formation, and finally to a suicidal act and completed suicide. Reference Casey, Dunn and KellyCasey et al (2008) suggest that we need to tailor interventions to specific aetiologies (reasons why that individual has suicidal thoughts in the first place), i.e. that we should treat the individual rather than the suicidal thoughts.

Efficacy of current assessment tools

There is no consensus regarding the most accurate and effective suicide assessment scales. Assessing current treatment methods can be unethical (Reference Pearson and StanleyPearson 2001). According to the findings of several comprehensive reviews, there is no single scale that achieves gold-standard levels of sensitivity and specificity with regard to the prediction of suicidal behaviour, and no consensus regarding the most useful (albeit limited) scale among those that are available (Reference Rothberg, Geer-Williams, Maris, Berman and MaltsbergerRothebrg 1992).

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS; Reference Beck, Kovacs and WeissmanBeck 1979) and the Reasons for Living Inventory (RFL; Reference Linehan, Goodstein and NielsenLinehan 1983) generally receive positive reviews. The BSS is an interviewer-administered tool that measures imminent threat of suicide. It possesses good psychometric properties (Reference Clum and YangClum 1995) and shows positive correlations when combined with self-monitoring strategies (Reference Clum and CurtinClum 1993). The RFL is a self-report instrument that focuses on the person's reasons for not killing themselves. This scale has good psychometric properties and has the ability to determine suicidal from non-suicidal individuals across many groups (Reference Ivanoff, Jang and SmythIvanoff 1994).

The Modified Scale for Suicide Ideation (MSSI; Reference Miller, Norman and BishopMiller 1986) establishes the intensity of suicidal ideas by addressing the desire for suicide, preparation and the patient's capability to make the attempt. It has good concurrent validity and a high correlation with the suicide component of the Beck Depression Inventory (Reference Miller, Norman and BishopMiller 1986). The Suicide Intent Scale (Reference Beck, Schuyler, Herman, Beck, Resnik and LettieriBeck 1974) evaluates the suicidal intent of individuals who have survived a suicide attempt, to help in the prediction of whether they will to go on to complete a suicide. It is the most frequently cited measure of suicidal intent in current literature (Reference Linehan, Comtois and BrownLinehan 2006) and has been recommended by many suicide experts (e.g. Reference Maris, Maris, Berman and MaltsbergerMaris 1992).

A new assessment tool, Srivastava and Nelson's Scale for Impact of Suicidality – Management, Assessment and Planning of Care (SIS-MAP), is used to assess the intervention needs of suicidal patients. A study of psychiatric patients who were potential admissions demonstrated that it was a good predictor of whether the patient required admission, with 74% being correctly classified in accordance with their clinic status (Reference Nelson, Johnston and SrivastavaNelson 2010). Another new instrument is Posner et al 's Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; www.cssrs.columbia.edu), which has been shown to identify greater numbers of suicide risk behaviours than other scales. The psychometric properties demonstrate good external validity, with data from three relatively large multi-site samples of adolescents and adults (Reference HughesHughes 2011).

A new approach involves identifying patterns of co-occurring risk factors associated with suicide, such as those related to health and to life stresses. Research suggests that suicide prevention practitioners will be more effective if they use strategies that target these combinations rather than individual risk factors (Reference Logan, Hall and KarchLogan 2011).

The role of compassion and suicide mitigation

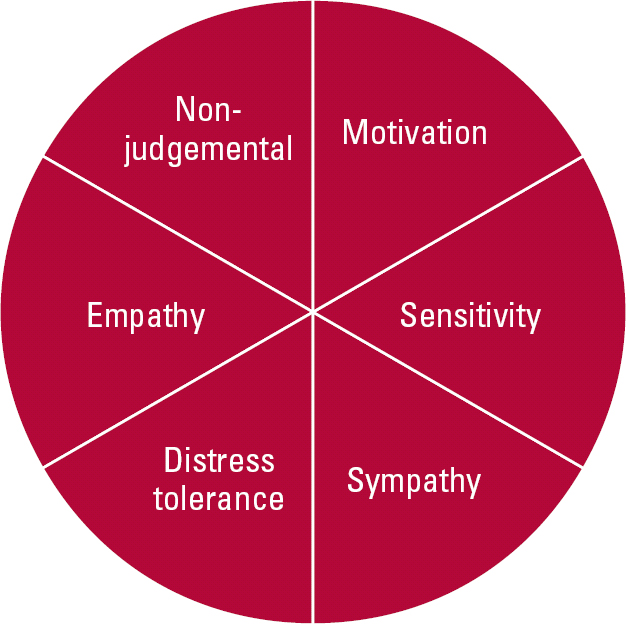

Compassion in medicine is commonly misunderstood as being linked only to traits such as warmth, kindness and gentleness. It is a major scientific error to dismiss compassion as too woolly a concept for serious study or application, given what we now know about the neurophysiology of affiliative relating (Reference Cole-King and GilbertCole-King 2011a). Gilbert's compassionate mind approach (Reference GilbertGilbert 2009)Footnote ‡ notes that our capacity for compassion evolved out of the capacity for caring that occurs in many species in the infant–parent relationship. Today compassion is commonly defined as a sensitivity to distress (in oneself or others) that is accompanied by a commitment to try to do something about it. Compassion is not a simple emotion or motivation but a complex combination of attributes and qualities. Given current research, Gilbert suggests that our human capacities for compassion depend on six essential qualities and attributes, as shown in Fig. 1.

FIG 1 Six essential qualities and attributes of compassion (after Reference Gilbert, Irons and GilbertGilbert & Irons (2005), with kind permission of the authors).

Suicidal patients under constant observation have reported positive feelings towards their observers if they found them friendly and willing to help, and noted a reduction in their suicidal thoughts if they felt that the observers were optimistic and gave emotional support (Reference Pitula and CardellPitula 1996). Conversely, the patients' distress was exacerbated if they perceived a lack of empathy or validation of their feelings (Reference Pitula and CardellPitula 1996). Reference Botega, Silva and ReginatoBotega et al (2007) emphasise that even brief training is sufficient to make significant improvements in attitudes towards suicidal patients.

In December 2008, the House of Lords ruled that, under the European Convention on Human Rights, healthcare providers have a particular duty to protect mentally ill patients who are at risk of suicide from harming themselves (Savage v South Essex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust 2008). This ruling adds to the fear that some health professionals feel and might lead to defensive rather than proactive practice. Thus, the threat of litigation or being the victim of a blame culture is detrimental to patients and also creates a poor learning environment. Furthermore, in their efforts to squeeze ever greater efficiencies and avoid bad practice, clinicians may fall into the trap of attempting to ‘name and shame’, thereby spreading fear through healthcare systems. Just as clinicians can create the conditions for healing, so organisational contexts can create the conditions for the facilitation (or stifling) of compassion (Reference Cole-King and GilbertCole-King 2011a).

When clinicians are under pressure, patients who are slightly more ‘complicated’ or complaining can become a source of irritation. This is not a criticism but a recognised observation; under such circumstances it may be more difficult for us to feel compassion (Reference Cole-King and GilbertCole-King 2011a). International evidence suggests that the quality of care on acute psychiatric wards is under threat (Reference Lelliott and QuirkLelliott 2004). Some patients perceive psychiatric wards as volatile environments and admission as a negative experience. Reference YoungsonYoungson (2010) states that healthcare professionals need to create a humane and supportive work environment so that caregivers can develop the inner resources for compassionate caring.

Undertaking a suicide risk assessment is a potentially life-saving clinical encounter, but the assessor is utterly dependent on what the patient chooses to tell them or not tell them. We suggest that, in the quest to develop the ‘perfect’ suicide risk assessment scale, researchers may have overlooked the importance of compassion and a therapeutic relationship during the assessment.

There are a number of both organisational and professional barriers in the identification and mitigation of suicide risk which we will now explore.

Barriers to identifying suicidal thoughts

Of the patients studied as part of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, 49% of the patients who died by suicide had been in contact with services in the previous week, 19% in the previous 24 hours. At final contact, immediate suicide risk was estimated to be low or absent in 86% of cases (Reference Appleby, Shaw and KapurAppleby 2006). We (C.-K. and colleagues) have suggested that these patients did not develop de novo suicidal thoughts, but that these were present and not elicited at their last clinical encounter. The reasons for this are likely to be multifactorial and influenced by both assessor and patient; the clinician might not have appreciated that the patient was at risk from suicide or self-harm, or asked the right questions or understood what the patient wanted to convey (Reference Cole-King and LeppingCole-King 2010a). There is evidence that suicide risk is often not identified in routine clinical assessments (Reference Malone, Szanto and CorbittMalone 1995).

Suicide risk factors can be grouped into three categories – the static and stable, the dynamic and the future – and each of these should be considered in an assessment (Box 2). There may be difficulty with the process of identification, assessment and response to such risks, so that opportunities to intervene effectively may be being missed.

BOX 2 Some suicide risk factors

Static and stable risk factors

-

• History of self-harm

-

• History of a mental disorder

-

• Family history of suicide

-

• Gender

-

• Age

Dynamic factors

-

• Suicidal ideation

-

• Hopelessness

-

• Psychiatric admission or discharge

-

• Psychological stress

-

• Poor adherence to treatment and ability to cope with problems

Future risk factors

-

• Access to a method of suicide

-

• Future interaction with psychiatric services in terms of general contact and interventions

Attitudes of healthcare professionals

There is a worrying failure among clinicians to explore suicidal thoughts in their patients (Reference Feldman, Franks and DubersteinFeldman 2007; Reference Oordt, Jobes and FonsecaOordt 2009; Reference Cole-King and LeppingCole-King 2010a). Fear remains among healthcare professionals regarding asking patients about suicidal ideas and plans. The Surgeon General of the USA suggests that healthcare professionals are failing to ask about depression and suicidal thoughts (US Public Health Service 1999). There may still be a belief among healthcare professionals that discussing suicidal thoughts with patients may directly lead to an increased rate of suicide. However, this has been disproved (Reference Gould, Marrocco and KleinmannGould 2005). Healthcare professionals must develop the skills to ask about suicidal thoughts in an empathic and compassionate way.

Individuals who have suicidal thoughts or have engaged in self-harm are often treated with lack of empathy, and even with hostility, by those they come into contact with, including healthcare professionals (Reference Herron, Ticehurst and ApplebyHerron 2001). It has been documented that 55% of emergency staff dislike working with patients who attend following self-harm; as many as 69% of people who presented with self-harm were dissatisfied with the emergency care they received (Reference Friedman, Newton and CogganFriedman 2006). In a review exploring attitudes towards clinical services among people who self-harm, one of the observations was that patients felt healthcare workers were concerned only with their physical health and not their mental state (Reference Taylor, Hawton and FortuneTaylor 2009).

Human factors, fear of litigation and the organisational culture

Most healthcare systems will have strategies in place to help promote patient safety and reduce suicide risk. Nevertheless, adverse incidents are inevitable and the concept of ‘human factors error’, only recently being applied in the field of suicide mitigation, promises to be useful. According to the National Confidential Inquiry, of the 6367 suicides of people previously known to services, 19% (1209 deaths) were considered preventable by the clinical teams seeing those patients (Reference Appleby, Shaw and KapurAppleby 2006). Furthermore, clinicians believed that in 75% of the suicides by patients known to services, suicide risk factors could have been reduced. It is clear that suicidal individuals have contact with a variety of people before their death and these contacts represent opportunities to intervene. The current preoccupation with characterising and quantifying risk and then ‘managing it’ is paradoxically increasing risk as practitioners may be too scared to identify it at all, lest they are unable to ‘eliminate’ it (Reference Cole-King and LeppingCole-King 2010b).

‘Physician education’

A systematic review of the effectiveness of suicide prevention interventions concluded that ‘physician education’ is one of only a few measures that lead to a significant reduction in suicide rates (Reference Mann, Apter and BertoloteMann 2005). Although doctors can be educated to increase their ability to detect suicidal ideas, this in itself may not result in any change in their management of suicidal patients (Reference Nutting, Dickinson and RubensteinNutting 2005). Negative attitudes and malignant alienation (including therapeutic nihilism of professionals towards ‘challenging’ patients) may intrude on the therapeutic relationship and actually contribute to a suicide (Reference Watts and MorganWatts 1994). Conversely, a more positive and understanding approach helps build a therapeutic alliance between suicidal patients and their therapists that can protect against suicide (Reference Collins and CutcliffeCollins 2003).

However, most NHS professionals currently have little or no specific structured training in suicide risk assessment and self-harm awareness, despite a Department of Health recommendation that all staff in contact with patients at risk of suicide should receive training at least every 3 years in recognition, assessment and management of risk (Department of Health 1999a). Of the 19% of suicides deemed to have been preventable, 12% (145 deaths) were considered by the clinicians to be related to deficits in training (Reference Appleby, Shaw and KapurAppleby 2006). Furthermore, suicide risk is often not documented in routine clinical assessments (Reference Malone, Szanto and CorbittMalone 1995), for a variety of reasons (Reference Cole-King and LeppingCole-King 2010b).

It is possible that by raising awareness and improving suicide risk assessment skills, some suicides could be prevented. More robust training could reduce morbidity and mortality (Reference Sudak, Roy and SudakSudak 2007). Reference Appleby, Morriss and GaskAppleby et al (2000) found significant improvements in suicide risk assessment skills, confidence and attitudes to suicide prevention following Skills-based Training On Risk Management (STORM®). Further studies showed that all groups of staff regarded STORM highly and thought it relevant to practice (Reference Gask, Lever-Green and HaysGask 2008).

Historically, a lack of consensus on suicide-related terminology in studies and no uniform approach to suicidal behaviour resulted in a great deal of misinformation (Reference HughesHughes 2011). Better structured universal training will continue to foster a consensus on the terminology surrounding suicide, thus improving understanding and communication.

Some suicide awareness training aims to change attitudes and promote intervention (Reference Patterson, Whittington and BoggPatterson 2007; Reference Griesbach, Russell and DolevGriesbach 2008) and there is evidence that even relatively minor interventions can prevent suicides (Reference Fleischmann, Bertolote and WassermanFleischmann 2008). A literature review commissioned by the Scottish Government has called for more research into suicide interventions and the empowering of suicidal individuals to resist acting on their thoughts by increasing hopefulness, personal resilience and reasons for living (Reference McLean, Maxwell and PlattMcLean 2008).

Reframing attitudes and approaches

Qualitative research illustrates that, where professionals do have negative reactions to patients with suicidal thoughts, it is usually for reasons such as feeling incapable of making a difference, and consequent frustration or resentment towards the patient. The patient is likely to perceive this as hostile, unsympathetic and uncaring, putting the therapeutic relationship at risk (Reference Thompson, Powis and CarradiceThompson 2008). Healthcare professionals who are empathic and compassionate encourage increased disclosure by patients about concerns, symptoms and behaviour, and are ultimately more effective at delivering care (Reference Larson and YaoLarson 2005).

An evaluation of one teaching intervention demonstrated that how professionals learnt from adverse incidents was significant. The opportunity to transform negative experiences through a re-framing of learning in a safe environment helped a group of anaesthetists to break out of practices that had become routine (Reference Gray and WilliamsGray 2011). We believe that a shift of viewpoint, a reframing of the experience, can be invaluable for a clinician whose patient dies by suicide. A doctor who has invested much in the care of someone with suicidal thoughts might see their suicide in black and white terms, either as a personal failure or as an inevitability. A more helpful perspective – similar to that which might be taken by medical and surgical colleagues whose patients die ‘despite’ the care they have received – is that the doctor's care might already have benefitted the patient experiencing suicidal thoughts – and their family and friends – by prolonging their life or improving their quality of life, for months or even years.

Emerging suicide prevention strategies

Community and social support

Social support and connectedness are protective factors against suicidal behaviour (Reference McLean, Maxwell and PlattMcLean 2008; Reference O'Connor, Rasmussen, Beautrais, O'Connor, Platt and GordonO'Connor 2011), making isolation and poor social connectedness risk factors for suicide. The many third-sector (voluntary) organisations set up worldwide can be helpful in supporting patients in the community (for a list of UK-based organisations, see Box 1 in Reference Hines, Cole-King and BlausteinHines 2013, this issue). The internet has become recognised as an extension of the ‘community’, acting as an invaluable information resource and, in some cases, a connection with someone who can help. However, it is important to remember that some internet sites promote suicide, and others contain triggering text and images. It is therefore imperative that before signposting people who have suicidal thoughts (or who self-harm) to any website, you have checked its content and credentials.

Loneliness, a key feature of social isolation, predicts depressive symptoms, suicide ideation and behaviour (Reference Masi, Chen and HawkleyMasi 2010). When categorised, the most successful interventions to prevent loneliness were those that altered individuals' social cognition, breaking the cycle of negative thoughts and poor self-worth. In essence, instilling self-compassion can be effective in protecting against and relieving depression (Reference Shapira and MongrainShapira 2010).

Clinical support

A key intervention is that of ‘caring letters’ (Reference Motto and BostromMotto 2001). Reference Carter, Clover and WhyteCarter et al (2007) demonstrated a 50% reduction in the repetition rate of hospital-treated self-poisoning among patients who received a postcard, although the proportion of patients repeatedly self-poisoning appeared not to have changed. Results from the Caring Letters Project showed a preference for receiving caring emails rather than postal letters following discharge from psychiatric hospital (Reference Luxton, Kinn and JuneLuxton 2012). There is also strong evidence for positive outcomes using telephone contact with people either following discharge after self-harm or a suicide attempt, or those falling into an at-risk sector of the population. For example, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving individuals admitted after self-poisoning found a significant reduction in suicide reattempt rates among those followed up by telephone 1 month after discharge (12% v. 22% in the control group) (Reference Vaiva, Ducrocq and MeyerVaiva 2006).

Observations on the long-term effects of twice-weekly telephone support and an emergency response for almost 20 000 at-risk elderly people indicated a standardised mortality rate for suicide that was 28.8% of the expected (Reference De Leo, Dello Buono and DwyerDe Leo 2002). The intervention was particularly effective for women, with connectedness and increased emotional support probably accounting for the positive effect, but it failed to reduce the suicide rate among men.

A large-scale multi-site RCT examined the effect of a 1-hour information session followed up by 9 contacts by telephone or in person on the number of deaths by suicide among suicide attempters in Brazil, India, Sri Lanka, Iran and China (Reference Fleischmann, Bertolote and WassermanFleischmann 2008). The intervention group had a 90% greater reduction in completed suicides than the control group.

Taken together, these studies show that there is an emerging evidence base for the development of simple, low-cost, compassionate interventions which have the potential to save lives.

Conclusions

Mental health workers may be held liable for patients who end their life by suicide, although it has been estimated that the number of cases that go to trial, even in the USA, is low (Reference Gutheil and JacobsGutheil 1992). However, following the House of Lords' ruling in Savage v South Essex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust [2008], litigation is possible if risk has not been correctly assessed or precautions have not been instigated where risk has been identified. In addition to excellent assessment skills, an important aspect of risk management is good medical record-keeping. If documentation is inadequate, a legal case can be devastating for the treating clinician even where there has been no negligence. We advocate the use of standardised nomenclature in the documentation of suicide risk assessment. We also suggest that, following a full assessment, clinicians should help all suicidal patients to create an immediate safety plan (Reference Cole-King, Green and Peake-JonesCole-King 2011b, Reference Cole-King, Green and Gask2013, this issue).

Mental health professionals who experience the death of a patient by suicide are often badly affected by it, particularly when they have tried all possible interventions (Reference Cole-King, Green and Peake-JonesCole-King 2011b). Occurrence of suicide during treatment or after assessment does not automatically imply negligence or failure: sadly, some patients will die whatever interventions are offered. Clinicians should change their perceptions of this fact: instead of therapeutic nihilism, they should hope that their interventions will enhance their patient's quality of life and at least postpone a suicide, so protecting that patient's family and friends from the pain of bereavement for that bit longer.

Notwithstanding the difficulties clinicians face, suicide prevention is successful for many and it remains of paramount importance in saving a significant number of lives.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Every year in the UK, suicide results in:

-

a 3000 deaths – double the number in road traffic accidents and second only to accidental deaths in the 15–44 age group

-

b 3000 deaths – double the number in road traffic accidents and second only to accidental deaths in the 45–70 age group

-

c 5000 deaths – double the number in road traffic accidents and second only to accidental deaths in the 45–70 age group

-

d 5000 deaths – double the number in road traffic accidents and second only to accidental deaths in the 15–44 age group

-

e over 6000 deaths – three times the number in road traffic accidents, with a worrying rise among middle-aged men.

-

-

2 According to the National Confidential Inquiry 2006, the proportion of suicides considered preventable by the clinical teams treating those patients was:

-

a 19%

-

b 12%

-

c 32%

-

d 12%

-

e 5%.

-

-

3 Gilbert's compassionate mind approach posits that our capacity for compassion evolved out of:

-

a social influences on our daily lives

-

b the capacity for caring in the infant–parent relationship that occurs in many species

-

c the trauma suffered as a result of the two World Wars in the first part of the 20th century

-

d the sudden boom of information made available to us as a result of the development of the internet

-

e the positive influence of Human Rights legislation that came into effect in the UK in 1998.

-

-

4 The proportion of emergency staff reported to dislike working with people who self-harm is:

-

a 25%

-

b 55%

-

c 27%

-

d 73%

-

e 58%.

-

-

5 The Department of Health recommends that healthcare workers should participate in suicide assessment training:

-

a every 5 years

-

b every year

-

c once a year

-

d every 3 years

-

e every 2 years.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | e | 2 | a | 3 | b | 4 | b | 5 | d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.