On 22 April 1638, Ṣägga Krәstos, an Ethiopian traveller in his early twenties, died in Rueil near Paris, guest of Cardinal Richelieu, First Minister of France (Renaudot Reference Renaudot1639: 196).Footnote 1 His documented history begins in Cairo in 1632, when he introduced himself to Father Paolo da Lodi, prefect of the Franciscan mission in Egypt and chaplain of Cairo’s Venetian consulate. Ṣägga Krәstos claimed to be the son of the Ethiopian Emperor Yaʿәqob (1597–1603 and 1605–07)Footnote 2 and to have fled his country after the new Emperor Susәnyos (1607–32) had killed his father in battle and usurped the throne. After some hesitation because of Ṣägga Krәstos’s lack of credentials, Father Paolo supported him with a letter of introduction to the Franciscans in Jerusalem, where Ṣägga Krәstos converted to Catholicism and pledged to return to Ethiopia as a Catholic king.

Following Father Paolo’s advice, in autumn 1632, Ṣägga Krәstos travelled to Rome with the friar’s letter,Footnote 3 under the aegis of the Congregation of Propaganda Fide, which had been created in 1622 to supervise Rome’s global missionary effort, ostensibly to seek the pontiff’s endorsement for his plan. Both the congregation and the Franciscans were eager to turn Ṣägga Krәstos into an instrument of Catholic proselytism, but they were also cautious, as supporting an impostor would result in embarrassment. Francesco Ingoli, Propaganda Fide’s secretary, vetted Ṣägga Krәstos and reported his findings to his superior, the Congregation’s prefect Cardinal Antonio Barberini the Younger (1607–71), one of the cardinal nephews in the service of Pope Urban VIII (1623–44, born Maffeo Barberini).Footnote 4

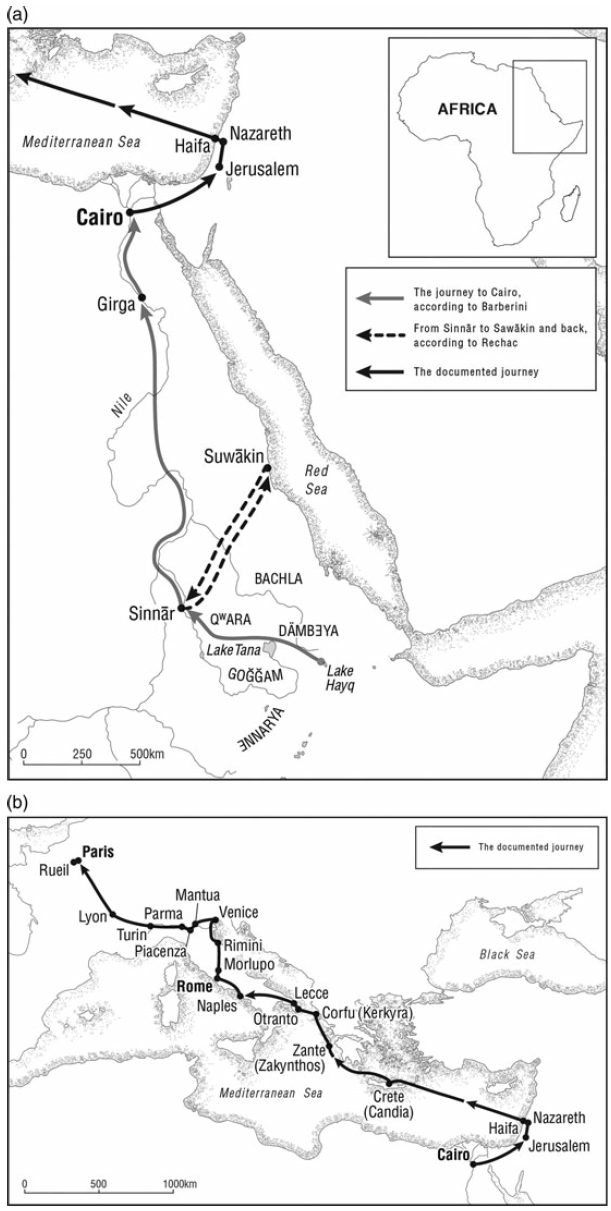

As part of the vetting process, Ṣägga Krәstos produced a 5,000-word autobiographical statement that consists of an exposition of his dynastic claim, the events leading to Emperor Yaʿәqob’s ascension and demise, his escape through the Nile Valley and his sojourn in Cairo and the Holy Land, a summary of his transit to Rome, and, in some versions, his experiences in Latin Europe (see Figure 2). Ṣägga Krәstos carried his own copy of the statement and, over the course of his journey through Italy and France, shared it with a variety of individuals who produced distinct versions by copying it, more or less accurately, and adding their own comments. Shortly after reaching Paris in the summer of 1635, Ṣägga Krәstos then published a heavily revised French version of his original statement, with the title Les estranges evenemens du voyage de Son Altesse, le Serenissime Prince Zaga-Christ d’Ethiopie (Zaga Christ [Ṣägga Krәstos] Reference Zaga and Giffre de Rechac1635). The small volume is the earliest known autobiography voluntarily written and published in Europe by an African-born author. It predates The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano (Equiano Reference Equiano1789), long regarded as the first African autobiography, by a century and a half.Footnote 5

Figure 1. Portrait of Zaga Christ by Giovanna Garzoni, 1635. Reproduced by permission from the Allen Memorial Art Museum.

Figures 2a and 2b. Ṣägga Krәstos’s journeys.

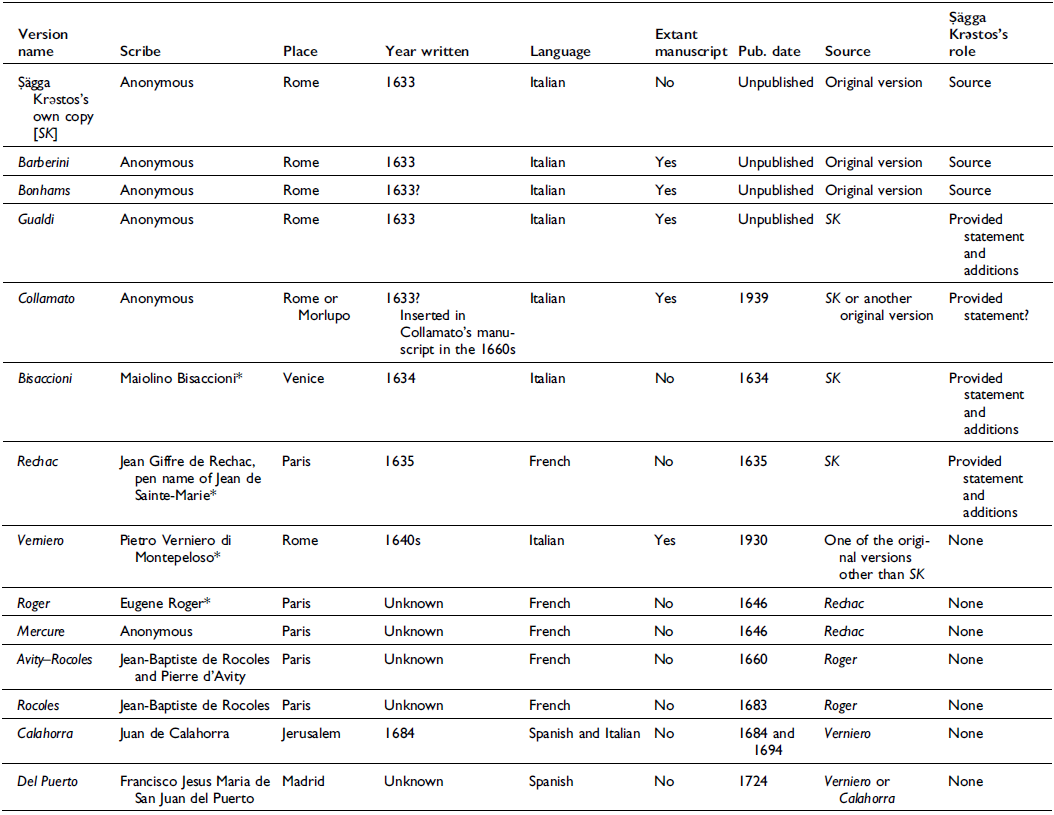

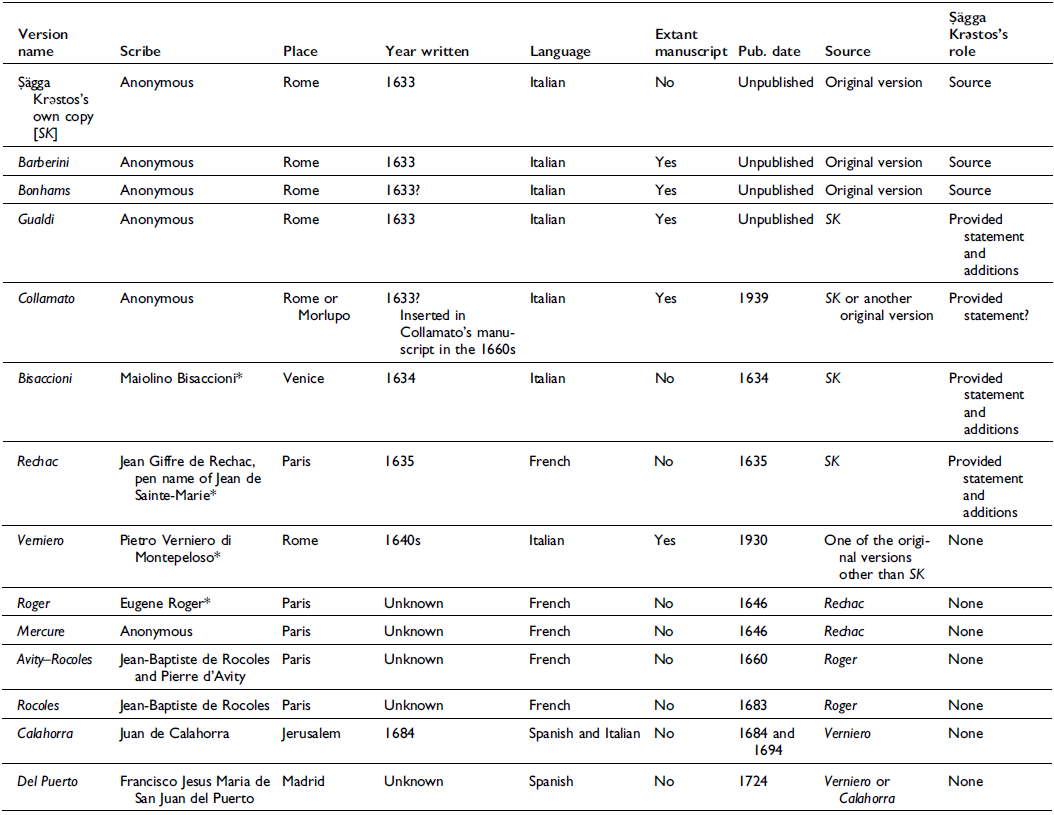

This article offers an overview of Ṣägga Krәstos’s journey and its context, discusses his dynastic claim, and maps the genealogy of his statement’s versions (Table 1). Following this, I present an annotated translation of what appears to be the earliest extant version of the statement, ‘Narratione del viaggio fatto dall’Altezza Serenissima del Signor Sagra Cristos figliolo dell’Imperator d’Ethiopia’Footnote 6 (‘Narration of the journey made by the Most Serene Highness Lord Sagra Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], son of the Emperor of Ethiopia’), hereafter referred to as Barberini, followed by excerpts from four other versions of the narrative. As supplementary material with the online version of the article, I present the original Italian text of Barberini. A more thorough overview of Ṣägga Krәstos’s journey and its context can be found in Salvadore (Reference Salvadore2021).

Table 1. Known versions of Ṣägga Krәstos’s autobiographical statement

Note: *Editors who included eyewitness additions to their version.

Ṣägga Krәstos’s journey

Ṣägga Krәstos met Father Paolo at a delicate time for the Catholic Church’s aspirations in Ethiopia. The Christian kingdom had attracted European interest since at least the early fifteenth century, when Ethiopian pilgrims and ambassadors travelling to the Italian peninsula drew the attention of their hosts, unfamiliar with the African continent but eager to recruit fellow Christians in the fight against the Muslim world. Ethiopians were identified as the subjects of Prester John, the legendary Christian king of European imagination who, throughout the Middle Ages, had mostly been associated with various locales in Asia (Beckingham and Hamilton Reference Beckingham and Hamilton1996). In the fifteenth century, Prester John became increasingly associated with Africa, and a growing number of European explorers, in particular the Atlantic-bound Portuguese, scouted first West and later East Africa for his kingdom. Finally, in 1520, a Portuguese mission made it to the court of Emperor Lәbnä Dәngәl (1508–40), allowing King Manuel I of Portugal to proudly declare that at last the pious Christian sovereign had been found (Krebs Reference Krebs2021: 142–53; Salvadore Reference Salvadore2017b: 123–53; Reference Salvadore2018).

After having praised Prester John’s power and piety from a distance, once in the kingdom, the Portuguese observed a different reality: in the 1530s, the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia barely survived an invasion by the Sultanate of Adal, while Ethiopian Christianity, once observed up close, appeared increasingly problematic to counter-Reformation Catholics (Natta Reference Natta2015: 288–90; Salvadore Reference Salvadore2017a: 72–4; Salvadore and De Lorenzi Reference Salvadore and De Lorenzi2021: 26–30). In an ironic twist, what Europeans knew as the kingdom of Prester John, and had once idealized for the piety of its sovereign and inhabitants, was among the first extra-European locales the newly founded Society of Jesus identified as a land of heresy in need of a mission. In the early 1550s, Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556) drafted instructions for a mission and the first fathers reached the Ethiopian court in 1555 (Salvadore Reference Salvadore2013).

After half a century of lacklustre activities, in the early seventeenth century the Jesuits converted a growing number of Ethiopian grandees, and in 1626 they secured Emperor Susәnyos’s vow of obedience to Rome. However, the project faltered rapidly because of widespread resistance by commoners, the traditionalist clergy, and much of the Ethiopian nobility. On 24 June 1632, an embattled Susәnyos declared religious freedom and facilitated the ascension of his son Fasilädäs (1632–67) shortly before dying on 16 September 1632. After refusing any compromise with the traditionalists, the Jesuits were first expelled from court and later from the country.Footnote 7 When Ṣägga Krәstos met Father Paolo in Cairo in March 1632, both the Franciscans and Propaganda Fide were aware of Jesuit difficulties and eager to lay the ground for an alternative mission by a different order. They were also increasingly weary of excessive Jesuit power overseas, their methods, and their autonomy from Propaganda Fide: Father Paolo and Ingoli saw in their young guest a unique opportunity to salvage Catholicism in Ethiopia, carve out a role for the Franciscans, and assert the congregation’s primacy.

Ṣägga Krәstos proved no less shrewd than his hosts, and within weeks of his first encounter with Father Paolo, he seized the day. Once in Jerusalem, he converted to Catholicism, then agreed to travel to Rome to pledge his obedience to the pontiff. In the ensuing weeks, he sailed to Italy on Venetian ships: he transited through Venetian Zante and landed in Otranto in October 1632; from there he travelled first to Naples and later to Rome, which he reached in early January 1633.Footnote 8 Despite Propaganda Fide’s efforts to keep him isolated, Ṣägga Krәstos met with a variety of Roman notables and diplomats stationed in the city. While Ingoli wanted him to return to Ethiopia under the aegis of a Catholic monarchy, his guest appeared determined to travel under English and Dutch patronage, causing grave concerns about potential Protestant meddling.Footnote 9 In November 1633, with his identity still unproven, Ṣägga Krәstos left Rome in the company of four Franciscans, who were assigned to support but also monitor him.

In December 1633, Ṣägga Krәstos reached Venice, where he spent six fruitless months attempting without success to obtain support from Republican authorities, while ostensibly negotiating a passage with English and other representatives.Footnote 10 Next, between July 1634 and April 1635, he was generously hosted, in order, by the dukes of Mantua, Parma and Piacenza, and Turin.Footnote 11 As the months went by, his Franciscan companions grew impatient, his plans kept changing, and the journey to Ethiopia became an increasingly distant mirage. The letters they sent to Ingoli exuded frustration with their delayed departure for Ethiopia and Ṣägga Krәstos’s unsettling hesitation.Footnote 12 While residing in Turin for nine months and confronting a long bout of illness, Ṣägga Krәstos was immortalized by the accomplished Giovanna Garzoni (1600–70) in the earliest known European portrait miniature of an African (Letvin Reference Letvin2021) (see Figure 1). In May 1635, he crossed the Alps and found his way to Paris, followed only by two of his Franciscan companions.Footnote 13 Within months of his arrival in August 1635, they too abandoned him, after obtaining their long-sought leave from Propaganda Fide.

In the meantime, Ṣägga Krәstos petitioned the French monarchy for support and secured a generous royal pension, presumably because of his potential value to France’s expansionist project in the Red Sea and French Capuchin plans for Ethiopia.Footnote 14 Two years later, in November 1637, Ṣägga Krәstos became a sensation when he attempted to flee Paris with Magdalene Alamant, wife of François Saulnier, a Parisian notable.Footnote 15 Apprehended and jailed, he defiantly refused to acknowledge the authority of his French prosecutors until Cardinal Richelieu had him released and hosted him at his estate in Rueil, where Ṣägga Krәstos died four months later on 22 April 1638.Footnote 16

Ṣägga Krәstos’s dynastic claim

During Ṣägga Krәstos’s sojourn in Rome, Ingoli strove to gather intelligence on his guest and his claim to be royalty. He attempted to find and invite to Rome some of Ṣägga Krәstos’s Ethiopian companions, but his agents failed. They could only collect the testimony of Dilaver Agha, an Ethiopian eunuch responsible for Cairo’s seraglio, who vouched for Ṣägga Krәstos but provided no evidence other than hearsay.Footnote 17 Ingoli also received an anonymous statement that identified Ṣägga Krәstos as a rogue monk, based on the authority of three Ethiopian monks from the monastery of Deir el-Muharraq.Footnote 18 Additionally, he received two more anonymous memoranda that explained away the naming discrepancies found in the statement and the absence of any reference to Ṣägga Krәstos in the well-known Jesuits’ letters sent from Ethiopia.Footnote 19 Like the eunuch’s affidavit, they were supportive, but also based on impressions and speculation. The same is true for two additional affidavits that Ṣägga Krәstos appears to have solicited from two Maronite Christians he had befriended while in Jerusalem; while supportive, they were also based on impressions and hearsay.Footnote 20

All in all, Ingoli had little to go on in the way of testimonies and opted instead for a thorough analysis of Ṣägga Krәstos’s own statement. In a table format, he compared, year by year, the timelines of Emperor Yaʿәqob’s rise and fall and Ṣägga Krәstos’s upbringing, either sensing or having been told that something was not quite right. His diligent reconstruction did not bear fruit, however. He could only admit to his superior Cardinal Barberini that there was no way to know whether Ṣägga Krәstos was telling the truth, and that, while an official endorsement was out of the question, their young guest, whom he liked very much, had to be supported out of Christian decency and, more pragmatically, because he could turn out to be a legitimate heir.Footnote 21

Had Ingoli been familiar with recent Ethiopian history, he would have realized that Ṣägga Krәstos’s claim to be Yaʿәqob’s heir did not hold up. In his statement, Ṣägga Krәstos claimed that his father had died in 1627, after ruling for twenty-three years; Emperor Yaʿәqob, however, reigned only from 1597 to 1603 and again from 1605 to 1607, when he was killed in his last battle against Emperor Susәnyos, after feuding with him for a few years. This must have been deliberate. In his narrative, otherwise impressively consistent with the Ethiopian royal chronicles, Ṣägga Krәstos had to stretch Yaʿәqob’s lifespan by two decades until the late 1620s to justify his own royal birth and the entire chronology of his journey.Footnote 22

Aside from his lack of written credentials and this stunning chronological impossibility, Ṣägga Krәstos’s behaviour is also telling. According to the friars who followed him throughout Italy and France, he had several opportunities to sail back to Ethiopia, either from Venice or Genoa, or even to travel through Persia, but he turned them all down, in spite of his professed desire to do the utmost for the Catholic faith.Footnote 23 Likewise, once in Paris, he did not seek support to repatriate; instead, he successfully petitioned Cardinal Richelieu for a pension that would allow him to stay. As one keen observer told Ingoli from Paris, Ṣägga Krәstos had no intention of leaving.Footnote 24

If Ṣägga Krәstos’s royal pedigree is to be dismissed, then who was he? His statement and experience leave no doubt that he was Ethiopian. A privileged or noble upbringing seems likely, as many of his interlocutors remarked on his exceptional manners and religious education, along with his impressive command of Ethiopia’s dynastic history. Because of his young age, Ṣägga Krәstos could not have been an eyewitness to the events he summarized in this statement, but must have had access to oral accounts or even the written accounts of the Ethiopian royal chronicles. Ṣägga Krәstos is likely to have been the son of a noble, caught in the violence and dislocation of the religious conflict that engulfed Ethiopia throughout the 1620s and 1630s: if so, he must have had some resources to flee Ethiopia and make it to Cairo, albeit not in the fantastic circumstances described in the statement. Alternatively, he could have been a rogue Ethiopian monk, as alleged by the anonymous report Ingoli received. In that way, he would have received an education that allowed him to play the part of a nobleman.Footnote 25

Neither Ingoli nor Ṣägga Krәstos’s many other European interlocutors were familiar with the Ethiopian chronology. Some suspected his imposture, but, overall, they opted for caution and afforded him the benefit of the doubt. As the different versions of his autobiographical statement and a diverse body of sources show, Ṣägga Krәstos was generously hosted at multiple courts. He went far by projecting royalty through a well-crafted demeanour, expressing religious and political ideas that impressed his hosts, and sharing a compelling story of exile. His success is in line with what Miriam Eliav-Feldon (Reference Eliav-Feldon2012: 101) has argued in her seminal Renaissance Impostors and Proofs of Identity: whenever ‘exotic’ visitors to early modern Europe ‘arrived appropriately dressed for the part, offering alliances and promoting riches and secret knowledge, they were never dismissed out of hand, no matter how far-fetched their claims, but treated with cautious respect’. Like other early modern impostors, Ṣägga Krәstos took advantage of the ignorance, anxiety and hopes of his European interlocutors looking for a foothold in the Horn of Africa (Davis Reference Davis1997; Groebner Reference Groebner2007; Snyder Reference Snyder2012; Zagorin Reference Zagorin2014). He used his Ethiopian identity and education to tell his interlocutors what they wanted to hear: that after renouncing his native religious practices and accepting Catholic truth, he was ready to lead his people to salvation.

Ṣägga Krәstos’s statements

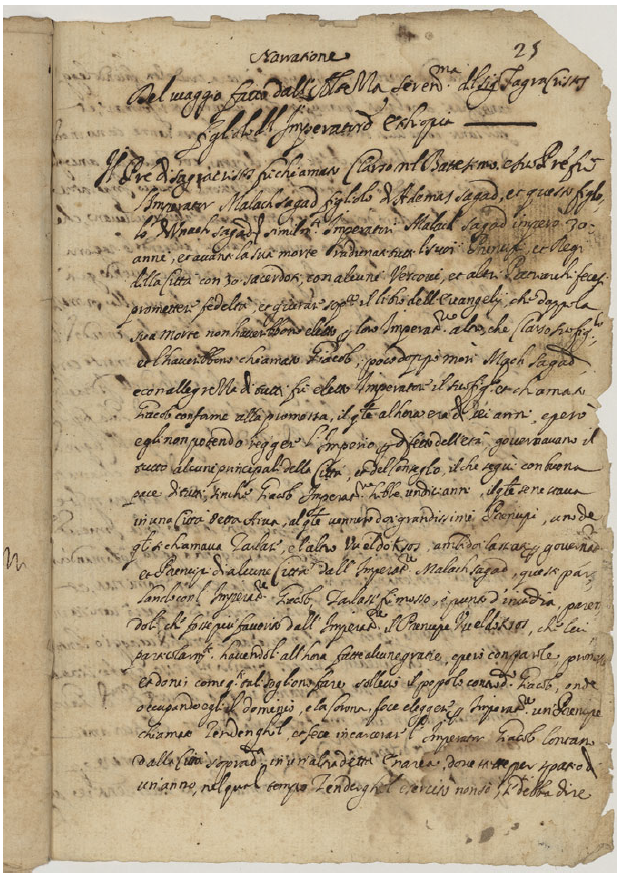

The version of Ṣägga Krәstos’s statement presented here – what I call Barberini, based on its archival location and likely recipient – can be dated with certainty to Ṣägga Krәstos’s Roman sojourn (see Figure 3). An earlier composition can be excluded because Barberini, along with all the other manuscript versions, was written in Italian, which strongly suggests that it was composed in Italy. Composition by the Franciscans in Cairo or Jerusalem can be excluded because, like all the early versions, Barberini refers to Ṣägga Krәstos’s arrival in Rome, and also because none of the individuals he met before arriving in Rome mentioned the existence of a biographical statement. It is only during and after his Roman sojourn that Ṣägga Krәstos shared the statement with his acquaintances and allowed them to copy it. Of all the extant versions of the statement, Barberini appears to be the oldest; it barely mentions the transit through southern Italy and the sojourn in Rome, while other early versions dwell on both and also include references to his subsequent journey. Its archival location is also telling: bound in codex 5142 of the Vatican Library’s Barberiniani Latini collection, it must be the original or an immediate copy of the statement, filed with Cardinal Antonio Barberini during the vetting process.

Figure 3. The first leaf of Barberini. Reproduced by permission from the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Barberini appears to be one of a batch of quasi-identical copies that were possibly all written at once and distributed to concerned parties. At a minimum, an additional copy was produced for Ṣägga Krәstos, who carried it with him for the rest of his life, allowing his interlocutors to copy it and produce additional versions.Footnote 26 As its third-person voice underscores, Ṣägga Krәstos did not write the statement himself: after spending a few months among Franciscans in the Holy Land and travelling with them to Rome, he had become proficient in oral Italian, but his ability to write did not appear to go beyond signing his name in an uncertain Latin script, which can be observed in a few signed letters he left behind.Footnote 27 Like the letters, his autobiographical statement was probably dictated to a scribe, either directly or possibly through an interpreter, which explains why all but one version are written in the third person. Nevertheless, the document’s content and the context of its production and its reproductions leave no doubt that Ṣägga Krәstos is the author.

One of the early manuscript versions – what I call Gualdo, based on the name of its recipient – is included in a letter that Ṣägga Krәstos wrote in November 1633 to one ‘Lord Knight Fraci Gualdi’, i.e. Francesco Gualdo (or Gualdi), secret chamberlain of Pope Urban VIII. In the introductory paragraph, Ṣägga Krәstos explains that he is about to depart for Venice, from where he hopes to return to Ethiopia, and that what follows in the letter is ‘a brief narration of the genealogy of my imperial lineage’ which he hopes will be a worthy addition to the addressee’s ‘museum’.Footnote 28 The reference points with certainty to Gualdo, and his famous Wunderkammer (Massimi Reference Massimi2003).

Gualdo can be identified as the first derivative version and the only one written in the first person. A few embellishments found only in this version, which I note in the Barberini translation, elucidate how Ṣägga Krәstos used his autobiographical statement to fashion himself. The most notable is a brief but significant reference to the narrative of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon – famously retold in the Kәbrä Nägäśt (The Glory of the Kings) – whose intercourse begot Menelik I, founder of the Solomonic dynasty.Footnote 29 Like the myth of Prester John, the narrative had much currency in Europe. Further, the letter speaks to Ṣägga Krәstos’s ability to ingratiate his interlocutors and obtain support, in this case for the journey he was about to start: ‘I will take the road to Loreto to visit the Most Holy House and I will continue my journey by land, I will reach Rimini, homeland of Your Lordship, where by your courtesy I will receive lodging in your home.’Footnote 30 Ṣägga Krәstos intended to travel to Venice on the old Flaminian Way and stop in Loreto to visit the Basilica della Santa Casa,Footnote 31 then stop in Rimini, where he hoped to count on Gualdo’s hospitality, whose family had properties in the city.

Another derivative version, almost identical to Barberini but ending abruptly with Ṣägga Krәstos’s sojourn in Jerusalem, which I call Collamato, can be found inserted in ‘Vicende del Tempo’, a manuscript chronicle authored by the Franciscan Francesco Maria Niccolini da Collamato (1626–?) in the 1660s.Footnote 32 Father Francesco referred to Ṣägga Krәstos’s arrival in the Holy Land directly in the chronicle – incorrectly dating it to 1630/31 – and inserted his copy of the statement in correspondence to year 1663 (probably the year of acquisition). Collamato could be considered one of the statement’s early versions, but the circumstances of its retrieval suggest otherwise. The friar claimed to have found it in the library of a conventFootnote 33 in Morlupo, near Rome, which can be confidently identified with the town’s Franciscan convent of Santa Maria Seconda, a convenient overnight stop for a party travelling north on the Flaminian Way. Given that throughout his journey Ṣägga Krәstos mostly boarded at Franciscan establishments, it could be speculated that Collamato was transcribed from Ṣägga Krәstos’s own copy during an overnight stay in Morlupo.

Next in chronological order is the earliest published version, which I call Bisaccioni based on the name of its editor, Maiolino Bisaccioni (1582–1663). A mercenary, novelist and historian, Bisaccioni was in Venice writing his 1634 treatise on the ongoing Thirty Years’ War when he met Ṣägga Krәstos. Having learned his story, he felt compelled to include it in his volume.Footnote 34 Bisaccioni Footnote 35 reads as an abridged version of Barberini with a few added elements: the historian added his own colourful considerations, along with a few details about Ṣägga Krәstos’s sojourns in Naples, Rome and Venice, learned from his conversation with him. Despite being the first published version of the statement, Bisaccioni appears to have neither inspired an additional version nor been known by anyone with an interest in Ṣägga Krәstos.

Another version with a story somewhat similar to Bisaccioni’s is what I call Verniero, which can be found in Father Pietro Verniero di Montepeloso’s Croniche ovvero Annali di Terra Santa (Reference Verniero di Montepeloso and Golubovich1930: Vol. 2, 277–301). The father was one of the Franciscans who met Ṣägga Krәstos at the convent of San Salvatore in Jerusalem. When he wrote the first version of his Croniche in 1636, he related Ṣägga Krәstos’s sojourn in Cairo and Jerusalem, based on his own recollection.Footnote 36 Years later, upon his return to Italy, he wrote a second draft – now lost – and then a third, which included a mildly edited version of the statement, almost identical to Barberini (Verniero di Montepeloso Reference Verniero di Montepeloso and Golubovich1930: Vol. I, lxxxiii–lxxxiv). Verniero must have accessed one of the early versions of the statement when he returned to Italy, to which he added his own considerations. His manuscript was not published until the 1930s, and Verniero does not appear to have led to additional versions except for an almost identical one – what I call Calahorra – which Father Francisco Calahorra included in his chronicle of the Holy Land, published first in Spanish (Calahorra Reference Calahorra1684) and later in Italian (Calahorra and Angelico da Milano Reference Calahorra and da Milano1694). The friar, who was in Jerusalem long after Ṣägga Krәstos’s transit, admitted to have lifted much of his manuscript from Verniero’s Croniche and was not in a position to include any additional information, other than perhaps what he had heard from other pilgrims (Verniero di Montepeloso Reference Verniero di Montepeloso and Golubovich1930: Vol. I, cii–ciii). Like Bisaccioni, Calahorra does not appear to have attracted much interest, despite appearing in print in the late seventeenth century. The same is true for what I call Del Puerto, which another Franciscan, Francisco Jesús María de San Juan del Puerto, lifted from one of the other three Franciscan versions and then included in his own chronicle of the Holy Land (Francisco Jesús María de San Juan del Puerto 1724: 374–87).

The opposite is true of another printed version – what I call Rechac, based on the name of its publisher – which accounts for the bulk of Les estranges evenemens du voyage de Son Altesse, le Serenissime Prince Zaga-Christ d’Ethiopie, a short book Ṣägga Krәstos published within weeks of his arrival in Paris (Zaga Christ [Ṣägga Krәstos] Reference Zaga and Giffre de Rechac1635). The publisher of record is Jean Giffre de Rechac, the pen name of Jean de Sainte-Marie (1604–60), an accomplished Dominican with a distinguished record of historical writing (Giffre de Rechac Reference Giffre de Rechac1647), but Ṣägga Krәstos’s authorship is confirmed in the dedicatory letter to the French Queen Anne of Austria (1601–66), which opens the volume. In it, Rechac explains that Ṣägga Krәstos ‘wishes nothing else than offering the King his service and asks humbly Your Majesty to accept and receive personally this report written by himself about his painful travels’ (Zaga Christ [Ṣägga Krәstos] Reference Zaga and Giffre de Rechac1635: unpaginated). Likewise, a contemporaneous collection of ceremonial memoirs reports Ṣägga Krәstos’s attempts to obtain a hearing from Louis XIII and relates that Ṣägga Krәstos ‘claimed to be the son of the King of Ethiopia. He said so in a book that he had got printed on this story’ (Godefroy Reference Godefroy and Godefroy1649: 797).

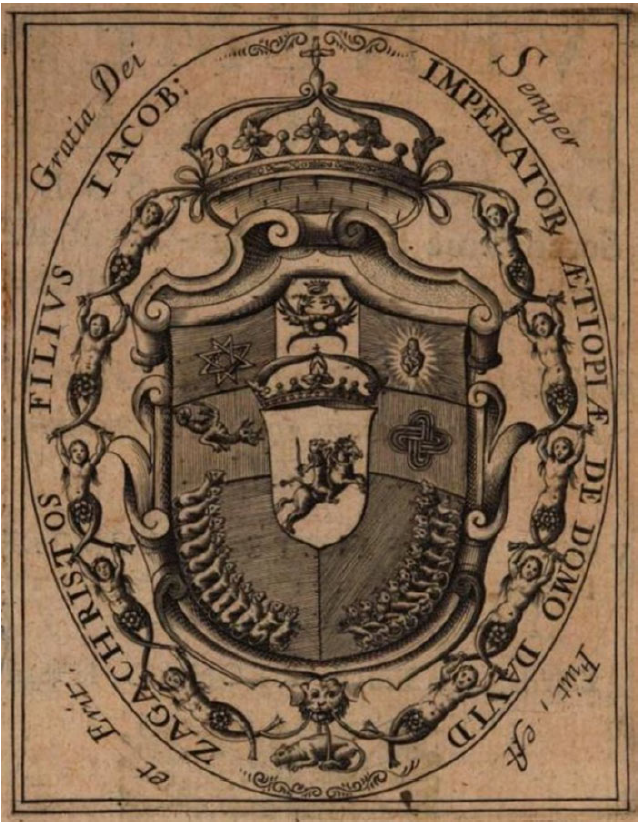

Apart from Rechac, Les estranges evenemens includes a richly adorned emblem presented as Ṣägga Krәstos’s coat of arms (see Figure 4), but clearly of European inspiration, and meant to impress the French public: many of its elements, listed in a thorough description, are of Ethiopian derivation, but others are borrowed from the European discourse on Ethiopia and Prester John (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1973). All in all, the volume is Ṣägga Krәstos’s ultimate self-fashioning effort: unlike Bisaccioni, Rechac is heavily restructured and incorporates a vast array of additional information. The introductory chapter cursorily summarizes the discussion of Ṣägga Krәstos’s lineage and Emperor Yaʿәqob’s rise and fall, and the following six chapters (Chapters 2–7) narrate his adventurous transit through the Nile Valley. Chapter 8 discusses the sojourn in Cairo and the Holy Land along the same lines as Barberini, while Chapter 9 summarizes the Italian and French legs of the journey and provides a few additional details missing from previous versions.Footnote 37 Rechac includes several additions meant to tantalize the French reader: for example, the wounding of Ṣägga Krәstos in a confrontation with one of Susәnyos’s underlings, and the hunting of exotic animals in the Nile Valley (Rechac, 9–12, 24–5). However, mixed up with what appear to be editorial additions are bits of information about Ṣägga Krәstos that, regardless of their truthfulness, are unequivocally the latter’s own additions. This is the case with multiple references to one of his companions, ‘Trita Mascal’, which is unmistakably a corrupted Ethiopian name, mäsqäl meaning cross in Amharic (Rechac, 8). Overall, Les estranges evenemens was clearly edited to present Ṣägga Krәstos as a wealthy heir and a peer to King Louis XIII, and to be marketed to a reading public with a growing penchant for the exotic. It is the only publication entirely dedicated to Ṣägga Krәstos to have ever been printed, and also the most consequential. While Bisaccioni is the first printed version of the statement, Rechac is the first published African autobiography, printed by Ṣägga Krәstos of his own volition.

Figure 4. Ṣägga Krәstos’s coat of arms in Rechac.

Unlike Bisaccioni, Rechac inspired additional published versions of the statement that have defined Ṣägga Krәstos’s legacy to this day. One can be found as a chapter in the Franciscan Eugene Roger’s pilgrimage account, La Terre Sainte (Roger Reference Roger1646: 349–60).Footnote 38 Roger was one of about fifteen French Franciscans dispatched to the Holy Land in the 1620s under the aegis of the French monarchy. He met Ṣägga Krәstos in Nazareth and was with him for ‘five months’.Footnote 39 His version of the statement, Roger, appears to be a combination of a cursory summary of Rechac and the friar’s own faded recollection of his first-hand experience from the early 1630s.Footnote 40 The Franciscan also included a discussion of Ethiopian religious practices and institutions and of the Solomonic myth. Following the introduction are the accounts of Ṣägga Krәstos’s genealogy, journey to Cairo and residence in the Holy Land. The first two read as abridgements of Rechac, while the last is, expectedly, extensive. It includes events Roger had direct knowledge of, such as Ṣägga Krәstos’s difficult stay in Jerusalem and his tense relation with its Orthodox community. The concluding paragraph reads as a summary of Rechac’s already brief overview of Ṣägga Krәstos’s journey in Europe, but it also refers to his death in Rueil. Although Roger accounts for only twelve of the volume’s 500-odd pages, the inclusion was prominently advertised on the front page as ‘a true relation about Ṣägga Krәstos, Prince of Ethiopia, who died in Rouel near Paris in 1638’. The choice was probably an editorial calculation to attract readers and capitalize on Ṣägga Krәstos’s posthumous fame among the Parisian reading public.

Ṣägga Krәstos’s legacy

Having been praised for his devotion by many of his acquaintances, in the years and decades after his death Ṣägga Krәstos was transfigured into a paragon of African sexual prowess and licentiousness, with a ‘great talent for gallantry’, as someone who ‘had made an infinite number of conquests’ (Vanel and Sauval Reference Vanel and Sauval1738: 147). A variety of commentators more interested in his nightlife than his birthright characterized his death as an unprecedented loss for women, and included in their prose and poetry more or less explicit references to the size of his penis, in line with the emerging trope of the hypersexualized African (Nederveen Pieterse Reference Nederveen Pieterse1992: 175; Toulalan and Fisher Reference Toulalan and Fisher2013: 505).Footnote 41 The erudite Valentin Conrart (1603–75), founder of the Academy of France, collected in one of his famous recueils (compilations) a variety of more or less scurrilous poems and epitaphs mockingly celebrating Ṣägga Krәstos’s sexual feats.Footnote 42 Another, more pedestrian recueil, by Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux (1619–92), includes an account of his affair with Magdalene Alamant, peppered with sexual innuendos.Footnote 43 Likewise, in 1662, a plagiarized version of Molière’s Sganarelle, printed with the title La Cocue imaginaire (The Imaginary Cuckold), referenced the attraction women felt for the ‘King of Ethiopia’ (Doneau Reference Doneau1662: 6). In this body of writings, one can find ironic references to Ṣägga Krәstos’s uncertain identity, including the famous line ‘the Prince of Ethiopia, the original or the copy’, which was widely quoted throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 44 However, the posthumous discourse that came to define the public memory of Ṣägga Krәstos was only tangentially concerned with his royal claim and instead was dedicated to his sexuality: in the aftermath of Ṣägga Krәstos’s scandalous arrest, his claim became secondary to his emerging identity as an exotic womanizer.

While a comprehensive discussion of the long-term trajectory of the European discourse on Ṣägga Krәstos and its context is beyond the scope of this article, a modicum of contextualization is in order. His years in Paris coincided with the early days of French overseas expansion, in particular with the first steps in the Senegal Basin and what would become the French Caribbean. France’s expansion in Africa and its involvement in the Atlantic slave trade led to a growing interest in Africa and Africans, and to the emergence of a francophone Africanist library and a racist French discourse on Africans (Cohen Reference Cohen2003: xxi–xxii, 6).

In 1655, Isaac La Peyrère published Prae-Adamitae, in which he argued that Africans were not the descendants of Adam, laying the foundation for what would later become the racial theory of polygenesis (Gossett Reference Gossett1963: 15). In 1684, the French traveller François Bernier published what has been regarded as the earliest post-classical classification of humankind and a precursor of modern theories of race (Stuurman Reference Stuurman2000: 3). While French intellectuals were taking their first steps towards the elaboration of what would eventually become biological racism, the ‘negative image of blackness reached a climax in French literature’ (Cohen Reference Cohen2003: 14), and Africans came to epitomize depravity, wickedness and treachery. This derogatory discourse on blackness was not a novelty in France or elsewhere in Europe, but, in the era, it appears to have reached new heights because of France’s rapidly growing engagement with Africa and Africans. In seventeenth-century France, notions of African sexual incontinence, lust and licentiousness, which had already been elaborated by scholars of the calibre of Jean Bodin and André Thevet in the mid-sixteenth century, became commonplace (Jordan Reference Jordan1977: 31; Leskinen Reference Leskinen2008; Lowe Reference Lowe, Earle and Lowe2005: 31–2).

Epitomizing this posthumous discourse on Ṣägga Krәstos is a heavily revised version of the statement I call Rocoles, found in Les Imposteurs insignes (Rocoles Reference Rocoles1683a: 387–403), a collection of essays on individuals accused of both dynastic and religious imposture throughout history. Its author, Jean-Baptiste de Rocoles (1620–96) plagiarized Roger but added his own scathing assessment, claiming that Ṣägga Krәstos feigned his intention of returning to Ethiopia and instead pursued a life of privilege and pleasure in Europe. Rocoles’ conclusion was in part correct, but hardly based on any evidence: he admitted that he considered Ṣägga Krәstos an impostor because, except for Roger, ‘everyone believed he was one’, and because of what he had learned in Paris in the 1640s.Footnote 45 This appears to be a disingenuous contention because although Bisaccioni was probably out of reach, Rocoles could hardly have been unfamiliar with Les estranges evenemens and Rechac’s supportive introduction.

Arguably, it was not evidence but his own prejudice and the posthumous discursive disparagement of Ṣägga Krәstos that persuaded Rocoles of his imposture. Tellingly, he characterized him as a ‘champion in the Games of Venus’, about which ‘[o]ut of decency, I will not say more on this here’ (Rocoles Reference Rocoles1683a: 401). Rocoles’ reasoning, grounded in this demeaning posthumous discourse, epitomizes the general involution of the European perception of Africa and Africans between the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries: Ṣägga Krәstos was included in Les Imposteurs because, as an African, he ought not to be trusted.

Rocoles was not the first author to call Ṣägga Krәstos an impostor in print: the German orientalist Hiob Ludolf had already done that in his Historia Aethiopica (1681), based on chronological reasoning and an advanced understanding of the Ethiopian historical record (Ludolf Reference Ludolf1691: 243–4). However, his was a text meant for a specialist reading public, which does not seem to have had much impact on Ṣägga Krәstos’s legacy, whereas Rocoles’ became a popular bestseller. Les Imposteurs went through numerous editions and became a foundational text for the early modern European discourse on imposture, marking the emergence of a new literary genre.Footnote 46 Because of its vast diffusion, it became one of the most cited texts on Ṣägga Krәstos: it was one of two sources mentioned in the entry dedicated to him in Moreri’s ubiquitous Dictionaire Historique (Moreri Reference Moreri1689: 1231). As late as 1886, the English biographer John H. Ingram plagiarized most of Les Imposteurs as his own Claimants to Royalty, and called Ṣägga Krәstos’s claim ‘pure fiction’ (Ingram Reference Ingram1882: 149).

Until the late nineteenth century, the few authors who concerned themselves with Ṣägga Krәstos did so based on one or more revised versions of his own statement and various derivative accounts of his escapades. It was only in the interwar period that some scholars approached Ṣägga Krәstos based on archival sources: Verniero’s Chroniche and Ingoli’s correspondence. This newfound perspective, however, produced short accounts mostly concerned with specific aspects of Ṣägga Krәstos’s journey (Cerulli Reference Cerulli1943: Vol. 2, 106–11; Crawford Reference Crawford1950; Kammerer Reference Kammerer1947: Vol. 1, 412–16). His overall experience remained surprisingly understudied and misunderstood: in 1985, an otherwise seminal analysis of the European discourse on Africa, Blank Darkness, argued that Rechac and Roger were the product of European imagination and Ṣägga Krәstos – featured on the cover according to the plate found in Roger’s volume – was a ‘mythical foreigner’ and a ‘creature of French discourse’ (Miller Reference Miller1985: 36–9). Three hundred-odd years after having impressed, albeit mendaciously, his European interlocutors and having been extended a treatment reserved, if not for a prince, then for a welcomed guest, Ṣägga Krәstos was turned into a figment of the European imagination and his statement, which is authentically Ethiopian, into a European text.Footnote 47

Introduction to the translation of Ṣägga Krәstos’s statement

The version of the statement presented here in translation is Barberini, integrated in the footnotes with significant alternative text from the other versions. Following are the concluding sections of Gualdo, Bisaccioni, Rechac and Rocoles. The first three are significant because they represent Ṣägga Krәstos’s own updates of his statement, relating to his experience in Europe. Ṣägga Krәstos did not contribute to Rocoles, but its conclusion is presented here because of its significant legacy. In the online version of the article, the reader will find the original Italian text of Barberini.Footnote 48

Care has been taken to keep the English translation as faithful as possible to the original Italian text; for the sake of clarity and readability, run-on sentences were split and necessary clarifications were added in square brackets. Names and toponyms are spelled according to Barberini, and their standard transliterations, in square brackets, according to the Encyclopedia Aethiopica (EA) (Uhlig and Bausi Reference Uhlig and Bausi2003–14). Parentheses and their contents are from the original manuscript.

Narration of the journey made by the Most Serene Highness, Lord Sagra Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], son of the Emperor of Ethiopia

Translated by Matteo Salvadore and Elia Italo Salvadore

[Ṣägga Krәstos’s lineage and Ya‘әqob’s rise and fall]Footnote 49

The father of Sagra Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] was baptized Clarso [Yaʿәqob],Footnote 50 and his fatherFootnote 51 was Emperor Malach Sagad [Mäläk Sägäd, baptized Śärṣä Dәngәl],Footnote 52 son of Adema Sagad [Admas Sägäd, baptized Minas], and this was son of Unach Sagad [Wänag Sägäd, baptized Lәbnä Dәngәl], all emperors. Malach Sagad [Mäläk Sägäd] ruled for thirty years and before his death he gathered all the city’s princes and kings,Footnote 53 together with thirtyFootnote 54 priests, some bishops, and other patriarchs. He had them pledge allegiance by swearing on the book of the Gospels, that after his death, they would appoint as their emperor no one but Clarso his son, and call him Giacob [Yaʿәqob].Footnote 55

A while later, Malach Sagad [Mäläk Sägäd] died and, to everyone’s delight, his son, who at the time was six,Footnote 56 was elected emperor Giacob [Yaʿәqob] according to the promise. As he could not rule the Empire because of his age, some princes of the city and of his council ruled over all, and all were at peace, until Emperor Giacob [Yaʿәqob] turned eleven.Footnote 57

He [Yaʿәqob] was in a city called Aina [Ayna]Footnote 58 when two great princes came to him, one called Zarlase [Zäśәllase]Footnote 59 and the other one Vueldoksos [Wäldä Krәstos],Footnote 60 who had both been appointed as governors of some cities by Emperor Malach Sagad [Mäläk Sägäd]. As the latter [Wäldä Krәstos] was talking to Emperor Giacob [Yaʿәqob], Zarlase [Zäśәllase] became envious, as it appeared to him that Prince Vueldoksos [Wäldä Krәstos] was favoured, and raised the people against Giacob [Yaʿәqob]. He [Zäśәllase] took over his [Yaʿәqob’s] domain and his crown, had a prince called Zendenghil [Zädәngәl] elected emperor [as Aṣnaf Sägäd II, 1603–04], and had Emperor Giacob [Yaʿәqob] incarcerated away from the abovementioned town [Ayna], in another town called Enarea [Ǝnnarya]Footnote 61 where he lived for a year.

During this time Zendenghil [Zädәngәl] exercised what one can call either absolute justice, unreasonable severity, or perhaps real cruelty, issuing laws for monks, priests and laymen alike, seeking to reform them all and make them into saints, as he believed himself to be. For this, he became hated by everyone, even by the one who had given him the kingdom, which is to say Zarlase [Zäśәllase] who took it away from him by killing him.

For the election of a new emperor, the people were divided in two parts, or two factions: some wanted to recall Giacob [Yaʿәqob], who was still in prison, advancing reasons for it, arguing that a new election was not necessary given that he already was the true and legitimate emperor, elected and crowned in conformity to the promise that everyone had made to Malach Sagad [Mäläk Sägäd], his father. Others, fearful of him after having been accomplices to his incarceration, did not want to agree to this, but wanted someone else among the Israelites, i.e. of the royal dynasty, elected. Among them was Susneos [Susәnyos] King of the GallaFootnote 62 and sonFootnote 63 of Fasiladas [Fasilädäs] and natural nephew of Malach Sagad [Śärṣä Dәngәl], and brother cousin of Giacob [Yaʿәqob],Footnote 64 whose mother was not the queen but a house servant called Hamelmal [Ḥamälmal Wärq]Footnote 65 (this [Susәnyos] is now Prester John).

There were many quarrels and fights and for a year they were without an emperor, until those siding with Giacob [Yaʿәqob] sent for him, with the consent of the mentioned Zarlase [Zäśәllase] himself, now happy with Giacob [Yaʿәqob] being emperor again; as he [Yaʿәqob] was [in a place that was] six months away, he [Zäśәllase] asked him to come by the end of the year. Those who still wanted Susneos [Susәnyos] sent for him and given that he was closer, a month’s distance away, he arrived earlier than Giacob [Yaʿәqob], but did not enter the city. Instead, he stopped nearby and his friends and many among the people went to him as they wanted to crown him emperor, but those who supported Giacob [Yaʿәqob] did not agree.

Once the year was over, they waited three additional months, as he [Yaʿәqob] was late because of the difficult journey. In order to keep the [support of] the people and to avoid crowning Susneos [Susәnyos] emperor, the princes supporting Giacob [Yaʿәqob] kept saying that he would arrive tomorrow, would arrive tonight, and they kept hope alive not only with words but also with actions and schemes: every night they sent out of the city many carriages, and during the day they had them come back claiming that they were Giacob’s [Yaʿәqob’s] carriages and precious things, and that he was near and such. But seeing that he was too late and understanding the trickery, all the people went out to get Susneos [Susәnyos], who entered the city, and after celebrating for ten days and on the tenth day he was crowned [as Sәltan Sägäd or Mäläk Sägäd III].

Five days after the crowning, Giacob [Yaʿәqob] arrived, and half of the people turned against Susneos [Susәnyos] and went to get Giacob [Yaʿәqob], crowning him emperor once again. Susneos [Susәnyos], realizing he could not resist Giacob [Yaʿәqob], fled and went to Galla, kingdom of gentiles,Footnote 66 where he had three children, two daughters and one son called Fasilidas [Fasilädäs].Footnote 67 Giacob [Yaʿәqob] entered in his Imperial City of Goghiam [Goğğam], where he took a wife and with her in five years he had three sons, the first called Cosmos [Cosmas], the second Damianos [Dәmyanos] or Theodoro [Tewodros], the third, whom is being discussed here, Sagra Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], also known as Lexanaos Cristos [Lәssanä Krәstos], Mammo,Footnote 68 and with a servant he had one son called Claudios [Gälawdewos].Footnote 69

At this time, Susneos [Susәnyos] gathered a big army and started to wage war and take over Ethiopia. Giacob [Yaʿәqob] sent the kingdom’s princes against him to fight, but the army of gentiles, being more powerful, little by little took over more and more of the country and arrived close to Goghiam [Goğğam]. Giacob [Yaʿәqob], who was in the countryside, was told, and mocked him by saying that, had Susneos [Susәnyos] reached him, he would have made him his stable boy. However, he was delaying [preparations] and he was happily celebrating the day before Easter, without acquiring neither weapons nor rations for the fight, until Susneos [Susәnyos] arrived within half a mile of the imperial pavilions. Seeing this, those in the countryside took arms, but being too late, they could not put up any resistance.

Hence in the twentieth year of his reign, Susneos [Susәnyos] entered Emperor Giacob’s [Yaʿәqob’s] encampment and pavilions, making a great slaughter and killing. [He did so] with his entire army of gentiles, a few Christians, some Jesuits – through whom Susneos [Susәnyos] and others in Ethiopia had left the Jacobite sectFootnote 70 and become Catholic – and Zelachristos [Śәʿәlä Krәstos],Footnote 71 his brother-in-law prince and general of his army.Footnote 72 Some fled, among them Emperor Giacob [Yaʿәqob] with six others on horseback, to the land of gentiles called Boram [Boorana],Footnote 73 about three month’s distance by foot. Susneos [Susәnyos] enchained all the princes and great lords he could grab and imprisoned them, and he had himself forcibly crowned emperor of Ethiopia, with all the things [i.e. celebrations] that are commonly done for an emperor. Then he had them all decapitated, with the exception of a few who are now in great misery. Then he divided the principalities among his soldiers, who were poor because they had followed him from Galla to Ethiopia. A year later, Giacob [Yaʿәqob] left Boram [Boorana] for Ethiopia, taking with him a large army, and entered [the region of] Amara [Amhara].Footnote 74

Upon learning this, Susneos [Susәnyos] sent thousands of people against him and the two armies fought near said Amara [Amhara]. However, Giacob’s [Yaʿәqob’s] army, having fewer weapons than its adversaries, fled before Susneos’s [Susәnyos’s] arrival, and Giacob [Yaʿәqob] also fled to the land of gentiles called Curage [Gurage]Footnote 75 to raise another army. One year later, he returned to Amara [Amhara] with a larger army, fought Susneos’s [Susәnyos’s] army again and won. He left from there because he wanted to complete his victory and went to Dambea [Dämbəya], near where Susneos [Susәnyos] wasFootnote 76 [camped], and again waged a very fierce war. In the fight, almost all of Giacob’s [Yaʿәqob’s] princes were killed together with the Emperor Giacob [Yaʿәqob] himself. [Yaʿәqob’s] aforementioned son Claudio [Gälawdewos] had been caught alive; after going to confession and receiving communion as a Catholic, he [Susәnyos] had him beheaded. Then, after twenty-three years of rule, Susneos [Susәnyos] achieved full control of the entire Ethiopian empire. And now [as of this writing], it has been five years and a half since this happened.Footnote 77

[Ṣägga Krәstos’s escape from Ethiopia]

While war was being waged, the three sons of Emperor Giacob [Yaʿәqob], which is to say Cosmos [Cosmas], Damanos [Dәmyanos] and Saga Christos [Ṣägga Krәstos], were on various small islands – and Saga Christos [Ṣägga Krәstos] was on the island called Haik [Ḥayq].Footnote 78 There, they received letters from their mother who gave them notice of what had happened and instructed them to flee because their lives were in danger. Having learned as much, they soon left. Cosmos [Cosmas] left towards the east, Damanos [Dәmyanos] towards other parts, and Saga Christos [Ṣägga Krәstos] towards the west;Footnote 79 the latter, departing from the said island, was accompanied by his godfather, who had been chosen by his father, and brought along many soldiers, two hunting lions, half a million in gold and a great quantity of jewellery.Footnote 80 Once landed on the mainland, he took 300 horses from his subjects, bought forty camels and, upon loading them, he left with 500 soldiers towards the west [out of Ethiopia], as it has been said.Footnote 81

The next day, which was a Monday, a great prince called Nagase [nägaš]Footnote 82 sent by Susneos [Susәnyos] arrived on the islands to catch them. However, unable to find them, he unleashed his anger on the islands’ inhabitants: beating, killing, plundering, breaking and burning everything. And he looted a priceless amount of gold and precious stones, in particular from the convent of some JacobitesFootnote 83 on said island, where they took altarpieces, books and solid gold vases.

[Ṣägga Krәstos in the kingdom of Sinnār]

Saga Christos [Ṣägga Krәstos] fled from the aforementioned place with great difficulty, and travelled for a month until he arrived in the land of gentiles known as Sennar [Sinnār] with his travel companions. All were exhausted and almost dead from the great difficulties they faced in finding food and water. Those gentiles, hearing that so many people were coming, came together to prevent them from passing through. They [Ṣägga Krәstos and his companions], unable to fight and find a way through, stopped for a while.

Their king [of Sinnār], called Herbat [Rubat I],Footnote 84 son of Gavon, sent someone to tell Saga Christos [Ṣägga Krәstos] that if he turned gentile, he [Rubat I] would have given him his sisterFootnote 85 as a wife and he [Ṣägga Krәstos] could have established a close friendship and kinship with him. He [Rubat I] did so many times and with great insistence, but Saga Christos [Ṣägga Krәstos] answered that he would never abandon the faith of Christians to become gentile and that he did not want his [Rubat I’s] sister as his wife because she was gentile. If he ever did marry her, he would require that she become a Christian and learn Christian ways and the worship of the true God. He [Ṣägga Krәstos] could not find any way to come to an agreement, given that he did not want to become gentile and the king of the gentiles did not want her to become Christian: therefore, he could not find any way to pass through.Footnote 86

It so happened that with said king there was someone who, despite being a gentile, was the son of Christians: his name was SalemFootnote 87 and his country was Bachla.Footnote 88 He covertly took council with Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] and his people and, given that he knew the roads of the country, he decided to join them and to leave at night, covertly. He did so, after stealing from the gentiles and his master 5,000 camels and other things, with 5,000 soldiers on the camels, so that he had gathered an army of 5,500 people. They agreed to travel back towards Ethiopia and arrived at one of its provinces called Abicini.Footnote 89 When one of Susneos’s [Susәnyos’s] grand captains, known as Sciumsyre,Footnote 90 learned this, he prepared a great army and moved towards him to wage war. They did not seek to avoid the fight but, enlivened, they readied their weapons with great courage and started to fight. In the fray, fiftyFootnote 91 died on Saga Cristos’s [Ṣägga Krәstos’s] side and thirty on the other side.

Once again, Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] and his people were forced to turn back to the land of the gentiles. When they crossed the Bachla region, Salem and all the people he had taken along with him stayed there. When they [Ṣägga Krәstos and his people] arrived near the city of Sennar [Sinnār], they camped outside it. The king, upon learning of [their presence] and seeing them, prepared his soldiers to wage war against them and sent a servant to see if Salem was there, but did not find him because he had stayed in Bachla as it has been said. Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] took counsel with his [people] on what to do and saw that they could not fight without losing everything, given that they were only a few and all exhausted, almost dead. Nor was there any possibility to go through a different way and they definitely could not go back towards Ethiopia because of Susneos [Susәnyos]. All together, they pleaded with said king of the gentiles to let them pass in exchange for twenty camels loaded with gold, clothing and rough gemstones.Footnote 92

[Ṣägga Krәstos in the Nile Valley]

The king [of Sinnār] agreed and once they had bought this passage through, they headed towards Turkey,Footnote 93 and after walking for twenty days, they arrived in ArabiaFootnote 94 where they were met by an Arab princeFootnote 95 who prevented them from passing. He sent word that he knew they had given to the king of Senar [Sinnār] twenty loaded camels and that he would not let them through unless they gave him twenty camels as well. They apologized that they could not give as much, because only a few [camels] were left – some having died, some having been eaten, some having been given away. Finally, he [the Arab prince] agreed to take only ten loaded camels and the two hunting lions Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] had with him.

Hence, he [Ṣägga Krәstos] travelled forth with only 300 of his soldiers – because his godfather had abandoned him and turned back with 100 soldiers – and fifty gentiles, who had taught him the way and started to serve the king of Sennar [Sinnār]. Another 100Footnote 96 of his company stayed in the city with the Arab prince. He gave Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] a guide to lead him to another place with Arabs, where he had to pay a huge sum of money in order to pass through. But only 200 passed through with him because fifty stayed in that place and fifty left him to cross the Red Sea and went towards Turkey.Footnote 97

Once past that place, having to cross a vast Arabian desert,Footnote 98 he [Ṣägga Krәstos] was burdened with infinite troubles, pain, and nothing to eat or drink – neither for themselves nor for the animals. The place was so sandy that the camels sank into the sand halfway up their legs and could hardly move. Even though they did nothing but walk day and night, they could hardly cover ten miles in twenty-four hours. The heat was so excessive that whenever even a little breeze blew, it was as if a flame of fire scorched one’s face and almost prevented one from breathing. They were all so thirsty and burned that they could not open their mouths to say a word. The [need to] sleep so oppressed them that at times some could be seen falling from their camels. They walked for months, without ever encountering other people, nor stones, grass, trees, or anything else – only sand and a scorching sky. Their food was a little bit of raw camel or horse meat, or that of some other animal, and they drank the milk of such animals when they could. For a while, they carried water in skins on the camels and, to avoid running out quickly, they rationed it: that is, each got little more than a cup per day. Once they ran out, they resorted to wetting their mouth with camel excrements [urine], and whenever they could have a cup of water, they purchased it with gold jewellery. The food given to the camels consisted of powdered dry camel meat which was fed to them by force. Once, after walking for twenty days without having found anything, they found a big tree with leaves and yellow fruit. Everyone, man and animal, ate some, without even noticing whether it was sweet, bitter, or some other flavour. It would take too long to tell of all the afflictions they suffered throughout Arabia;Footnote 99 it is enough to have mentioned them in general terms. In addition, Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] did not eat for two entire years neither bread nor salt. Although he found bread in some places, he could not eat it because it was not made of wheat, but he settled for animal milk.

With all these afflictions, of the 200 soldiers and servants he had with him, only thirty were left, with only fifteen camels, and so rode two per camel. All the others had been left behind – either because they died, were crippled or, no longer having a camel, were unable to keep walking through the sandy desert. Some left looking for food and fell behind; some found some Arab [to stay with] or farmhouse to stay at; others stayed behind for one reason or another.

[Ṣägga Krәstos in Cairo]

Once Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] arrived in CairoFootnote 100 with thirty men and fifteen camels, all the TurksFootnote 101 were amazed and alarmed. An Armenian, who had been to Saga Cristos’s [Ṣägga Krәstos’s] home in Ethiopia, immediately recognized him and said so to a Grand Turk, the Emperor of Constantinople’s eunuch [Dilaver Agha] charged with the Grand Turk’s seraglio.Footnote 102 By sheer chance, this eunuch was Ethiopian and he immediately sent a servant to bring Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] to his home. Unable to host all thirty people, he told Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] to retain only fifteen, spreading the others across Cairo in the houses of Christians, so that in some there was one [Ethiopian], in some two, in some more. Of the fifteen that remained with Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], three dined in the house of the Turk [Dilaver Agha], and the others with one Christian or another. They stayed in Cairo for an entire month. They sold all their camels and provided for themselves with the proceeds. Once depleted, two of Saga Christos’s [Ṣägga Krәstos’s] servants made themselves Turks,Footnote 103 five converted to the Greek [Orthodox] faith, three fell ill, and others went out to various places looking for things to do to support themselves and their master. Only eight stayed with him in Cairo.

During the day he [Ṣägga Krәstos] ate at the house of the mentioned Turk [Dilaver Agha] and at night he went to sleep in the house of the Armenian, who knew him from before and knew of his travails and escape. He [Ṣägga Krәstos] was afraid to sleep in the house of the Turk [Dilaver Agha], knowing that at night they might invite a Turkish priest or preacher to force him to renege on his Christian faith and turn Turk.Footnote 104

It so happened that one day during CarnivalFootnote 105 Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], while in the Armenian’s house, drank a bit of date liquor.Footnote 106 It caused him great pain and dizziness and at night, while he was sleeping, he felt blood seeping out of his ear. He woke up and informed the Armenian, who sent for the consul of Venice’s physician. Being Catholic he [the physician] did not want to go to Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], who was a Jacobite, but said that he [Ṣägga Krәstos] would give him medicine if he came to him. In the morning, he [Ṣägga Krәstos] went and [found himself] in the company of many, and through the consul’s interpreter, he [the physician] told him what to do.

In the meantime, the consul learned from his interpreter that the Ethiopian emperor’s son was there. He invited Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] into his house and through the interpreter asked him who he was, where he was coming from, and why. Having been briefed on everything by the Armenian, the consul brought him [Ṣägga Krәstos] into the presence of Father Paolo da Lodi, Observant Friar Minor of the Province of San Francesco, who was in Cairo as an apostolic missionary.Footnote 107 They all urged him [Ṣägga Krәstos], for the well-being of his body and soul, and because it was an easy journey, to go to Rome, introduce himself to the pontiff, kiss his feet, and pledge obedience to him, like almost all kings and Christian princes did. As a boat to VeniceFootnote 108 was available, they advised him to leave immediately. The consul promised to give him provisions for the trip, letters of recommendation that would identify him to the [Venetian] Republic.Footnote 109

But he [Ṣägga Krәstos] refused to do so because he wanted to see Jerusalem, and because he had been travelling for almost four years, with much suffering. The aforementioned Father Paolo da Lodi told him that if he wanted to go to Jerusalem, he would help by giving him letters of recommendation for the convent of Italian friars there.Footnote 110

As he [Ṣägga Krәstos] was very determined to go, he [Father Paolo] told him to come back the following day for the letter [of safe conduct], but to be cautious and not tell anyone. Not only would it have been dangerous for all the friars, but had it [the plan] reached Turkish ears, they would have cut his [Ṣägga Krәstos’s] head [off] and sent it to the [Ottoman] Emperor of Constantinople. Taking along only one [trusted] servant for fear of being discovered, he [Ṣägga Krәstos] visited Father Paolo many times until, after three days, he gave him the letter without his servant knowing.

But he [Father Paolo] made a mistake because he gave him [Ṣägga Krәstos] the one [letter] for the [Venetian] consul, which recommended him [Ṣägga Krәstos] to Venice. The next morning, [unknowingly] he [Ṣägga Krәstos] went with that [the wrong letter] to Jerusalem, with fifteen servants. When they were already two or three miles away from Cairo, the consul’s servant caught up with him, carrying Father Paolo’s right letter. He gave it to Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] and told him that earlier he [Father Paolo] had made a mistake – and then the two servants [who were with Ṣägga Krәstos] saw and understood. After fifteen days, he reached Jerusalem, but with only eight of his servants because the others had remained behind, held by the Turks because he [Ṣägga Krәstos] could not pay the custom duties in some places.

[Ṣägga Krәstos in Jerusalem]

Once in Jerusalem they all went to the hospice of the Ethiopians, or Abyssinians, where they all welcomed Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] as son of their emperor, the best way they could.Footnote 111 But one of the two servants called StatiosFootnote 112 [Ewosṭatewos], who had seen when the consul’s servant had given [Ṣägga Krәstos] Father Paolo’s letters, went to the patriarch of the Greeks, to the bishop of Armenians and to the Egyptian superior. He accused him [Ṣägga Krәstos] of being an Italian Christian,Footnote 113 who had letters for the farenj [färänğ] friars,Footnote 114 which is to say the Italian friars. He told them not to believe he [Ṣägga Krәstos] was really a Jacobite in light of the letters he was carrying from Cairo and other bad things that an infidel can and is used to say against one who had the courage to abandon perfidy and embrace the faith. Upon hearing this, they were very displeased, but they did not have much time to talk to [Ṣägga Krәstos] because in the morning, with four servants, he went to the Jordan River to wash in that holy water as it is the custom of those people.

Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] did not dare go in person to the friars’ convent [in Jerusalem] for fear of the Turks and to avoid anyone suspecting his change of heart. [Instead] he took his letters [and hid them] inside a book carried by the animal they were leading, to show them stealthily to the Italian friars near the Jordan. [However], his servant Statios [Ewosṭatewos] furtively took them and hid them under a rock to later make them public. Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] looked for them to give them to the friars before the arrival of the pasha of the Turks, who was not far. He did not find them, and being certain that Statios [Ewosṭatewos] had taken them, as it were, he started to argue with him and threatened to have his head cut off by the pasha like a thief. He [Ewosṭatewos] denied it [stealing the letters] and he [Ṣägga Krәstos] ran to the pasha with his servant [Ewosṭatewos], who told him to stop and wait until the pasha’s arrival. Once he [the pasha] arrived, he first spoke to Statios [Ewosṭatewos] having been the first accuser. He [Ewosṭatewos] said that Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] was taking letters to the Italians and that he wanted to go to Rome and lead soldiers to Jerusalem, and that his head had to be cut off and similar things. But as he could not speak Arabic and express himself well, the pasha did not understand well, but became suspicious, after hearing minced words such as Italians, Jerusalem, taking, cutting his head off and similar things.

Then Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], who knew how to explain himself in Arabic better, started to talk and said that his rogue servant had stolen the letters and did not want to return them. The pasha asked for the letters and threatened to have his [Ewosṭatewos’s] head cut off immediately if he did not return them. He returned them, and the pasha asked what kind of letters they were and what they said. Again, with his evil tongue, he [Ewosṭatewos] said that they were by Italians who wanted to take Jerusalem. Having heard this again, the pasha became very suspicious, but seeing that Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] had letters of recommendation from the Armenians and others that were similar to the Italian ones, he returned them to him. However, to dispel any suspicion, he ordered that they both be chained at the neck, until they could find a good interpreter who could understand them.

A Turkish prince, seeing this and moved to compassion for Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos], who appeared to be what he claimed, told the pasha that it was not right to treat the master like the servant by keeping them bound to the same chain. But he barbarously answered that in their land all those who do not believe in Maomet [Mohammed] are slaves and that they would be treated in the same way. While they were chained together, that bad servant started to insult and threaten his master Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] by saying that as soon as they reached Jerusalem, the pasha would find an interpreter and have him [Ṣägga Krәstos] killed. He [Ewosṭatewos] again reproached him for his change of faith, for having left their teacher DioscorusFootnote 115 to become ItalianFootnote 116 Catholic and other countless insults. He [Ṣägga Krәstos], despite fearing the pasha, replied that Dioscorus was a blind teacher and his followers were also blind and that they would all fall into the pit of hell with him. Finally, after having crossed themselves with holy water, Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] managed to dispatch his letters while the two were being taken to Jerusalem, chained on the same camel.

Once arrived two hours after dawn, they were taken in front of the house of the pasha’s servant. An Egyptian approached them and asked them what they had done to be chained, having realized that one was clearly master and the other servant. Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] told the entire story; Statios [Ewosṭatewos] wanted to do the same but was not understood by the Egyptian, who made a deal with Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos]. He told him in the ear, [‘Tell me] what you want to give me and I will make the pasha free you.[’] Without saying much, he [Ṣägga Krәstos] secretly took off from his finger a ring with a very valuable diamond, and gave it to him. He [the Egyptian] went to the pasha, who summoned both. The pasha instructed the Egyptian, who claimed to understand their language, to be the interpreter as he did not have a better one. He [the Egyptian] started to speak and negotiate on Saga Cristos’s [Ṣägga Krәstos’s] behalf, saying that the servant was a sad person, a thief and that he deserved to be punished. So he was sentenced to prison and Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] was freed, and the pasha took his [Ṣägga Krәstos’s] camel as payment as he had nothing else to give.

Hence, God had freed Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] from the hands of Cairo’s pasha, who wanted him to become Turkish [i.e. Muslim] and he ordered to seek him out so that he could send him to Constantinople as a gift for the Grand Turk. However, he could not find him because he had already left for Jerusalem. Now again he [God] freed him through an Egyptian, from the hands of the pasha of Jerusalem and from his bad servant’s accusations. The latter, after three days in prison, was asked if he wanted to bail himself out, but having nothing and unwilling to become Turk, as the pasha wanted, he was given thirty-three beatings and after thirteen days in prison was set free. He went again to the patriarch of the Greeks, the bishop of the Armenians and the Egyptian superior, to whom Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] had already given the letters of recommendation given to him in Cairo. And [the servant] again whispered and spoke ill of him, telling them all what had happened and that they should not believe that he was a Jacobite because he had made himself Italian.

Hence, they all turned against him [Ṣägga Krәstos] and persuaded his servants to abandon him. Together with the patriarch, they conspired against him while he was [staying] in a very ugly room in the house of the Ethiopians in the city,Footnote 117 mistreated by everyone, whereas his servants were very well treated by the patriarch and the others. They all tried to persuade Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] not to be fring [färänğ] – that is, Italian – but Jacobite.Footnote 118 However, as he was firm in his resolution, they tried to have his head cut off. As he was persecuted by everyone, not even the Italians dared to greet him for fear that something bad would happen to them; only their interpreter sometimes consoled him.Footnote 119

With Easter approaching, he entered with the friars in the Holy Sepulchre and gave a fright to the astonished guardian who was out of his mind. On this occasion Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] managed to talk to the friars, who, seeing his good soul, advised him to go secretly to Nazareth, where he would have been safer with the friars and hidden from the Turks, because certainly had his dealings been discovered, his and the friars’ heads would be gone. He accepted the good advice and, with three companions who seemed less ungrateful, he left stealthily while the others stayed.Footnote 120

[Ṣägga Krәstos in Nazareth]

A few days after arriving in Nazareth, those three servants, having to toil a bit there, left. Saga Cristos [Ṣägga Krәstos] was inconsolable: he found himself all alone, not knowing how to speak Italian with the friars, and the friars unable to speak Arabic or any other language with him. Day and night, he was always crying over his misfortunes. Two months after he [Ṣägga Krәstos] had arrived in Nazareth, the abovementioned Father Paolo arrived from Cairo, having been appointed Guardian of Jerusalem.Footnote 121 He [Father Paolo] was overjoyed to see him [Ṣägga Krәstos] there and asked him about his servants, and he [Ṣägga Krәstos] explained everything to him the best he could. The father exhorted him to be a true CatholicFootnote 122 to be able to gain paradise, and not do like his servants, who, because of their perfidy, would go to hell. To better ascertain his true faith and give him a better foundation in it, he [Father Paolo] took him along to Mount Tabor and other holy places. Once returned to Nazareth, he had him swear on the Gospel that he would always be CatholicFootnote 123 and never return to the faith of the Jacobites,Footnote 124 even at the cost of his life. He did so gladly. As Father Paolo wanted to leave for Jerusalem, he told him [Ṣägga Krәstos] to stay there, telling him that he would send him a letter proving that he was Catholic. And he would send two friars with whom he would embark for Rome to go and kiss the feet of the most Holy Pope. Once he received the letter, he did what he had been persuaded to do and left with the Guardian of NazarethFootnote 125 and arrived in Rome in the house of the Reformed Observant Minors of Saint Francis.Footnote 126

[Ṣägga Krәstos in Italy according to Gualdi]

… I [Ṣägga Krәstos] left with the Guardian of Nazareth, taking the route of Zante [Zakynthos]. I arrived in Otranto and later in Naples, and in a few days, I arrived in Rome at the convent of the Observant Reformed Friars Minor on 7 January 1633 in San Francesco in Trastevere otherwise known as di Ripa.Footnote 127 After a few days I went to live in San Pietro Montorio, also known as Monte Aureo in the convent of the abovementioned fathers,Footnote 128 where I stayed until the present day …

[Ṣägga Krәstos in Italy according to Bisaccioni]

… [Ṣägga Krәstos] landed in Zante [Zakynthos] and upon changing boat he went to Corfu [Kerkyra], from there he landed in Otranto and transferred to Naples. He entered the city on Saturday night and lodged in the convent of the Cross of the Observant Fathers.Footnote 129 A journey so long that could have turned Midas into a beggar had made this prince spend all the gold and jewellery except for two trunks full of Ethiopian clothes and in particular two turbans – one of spun gold with some jewels and the other one of red cloth laced in gold, also with jewels – and two royal mantles or capes, decorated with pearls and small diamonds [and] small rubies. [These were] enough to uplift the unhappiness he was fleeing for some time. In the morning, while he was looking for a room where he could say his prayers, the trunks were not found: the stable boy said he had unloaded them at the door of the monastery, and the fathers [said] that they had not received them. Everyone flocks to see novelties; the foreigner is the first to be besieged with visits and distracted from taking care of his home, so the thief can easily reach for its loot. He resorted to justice, but found nothing; this was the last of the goods of his father and country. Here he is: naked, unknown, pilgrim, king banned from his kingdom, and victim of calamities.

As much as the plebeians of Naples is friendly to theft, its nobility is liberal and courteous: he received clothes and gifts and stayed only thirteen days. He moved on to Rome, where he arrived on 6 January 1633 and lodged at San Francesco a Ripa, then in San Pietro MontorioFootnote 130 … He left from Rome in November, and thanks to pontifical orders he was hosted throughout the state of the Church, and provided with board and transport by governors, bishops and ministers …

He came to Venice, where he still is today as I am writing, on 17 June [1634]. He is lodged at the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore of the Benedictine Fathers, who are revering and entertaining him a great deal, because of a simple letter of the Father Abbot of San Paolo in Rome,Footnote 131 who recommended him. He is about to leave for France and England, or Holland, having sent things by sea, while he will go by land to France, to avoid the danger of the Turk he already had past problems with. Then he will go towards Congo on this side of the Cape of Good Hope. Four Reformed Observant FathersFootnote 132 are following him to assist in the interests of faith and to cultivate the vineyard of the Lord …

[Ṣägga Krәstos in Italy and France according to Rechac]

He [Ṣägga Krәstos] embarked together with the monks and was so lucky to meet on board a Venetian nobleman who once had visited Ethiopia and, thus, had known him in his magnificent glory.Footnote 133 The conversation with this nobleman helped him overcome a little the miseries of his journeys, and he arrived in Zanthes [Zakynthos] with fewer regrets. From there, they sailed to Corfu [Kerkyra], where they met Jerosme Moresimo, the most famous commander of the Venetian warships and vessels.Footnote 134 Moresimo received the prince with all kinds of honours and regards and armed a small boat specifically for him that took him to Otranto.

There, the governor and ruler of the city, prompted by rumours of plague, refused to let him in and to talk to him for eight days. Only then was he received and treated at the palace of the governor, who quickly informed the viceroy of Lechy en l’Ampouille [Lecce in Apulia]. The prince then went there and was received with all imaginable magnificence: the archbishopFootnote 135 came personally to meet him, followed by numerous lords and a huge crowd of ordinary people, all curious about him. The viceroy, lying sick in bed, could not attend. However, four days later, when he got better, he came to greet him at the archbishop’s, where the prince was residing, and brought him a lot of presents in recognition of his noble status.

The prince appreciated these attentions very much and asked him the favour of an escort to Naples, which the viceroy gave immediately, by sending messengers in all directions to inform the governors of the places the prince would cross on his way to Naples. These governors were required to show the prince the best regards suitable for his high status. The prince then left Lechy [Lecce] with many noblemen accompanying him as ordered by the viceroy. He met the Prince of Avetrana,Footnote 136 who gave him a very warm welcome. This prince gave him a very expensive and luxuriously harnessed horse as a gift.Footnote 137 He [Ṣägga Krәstos] rode the horse to Naples, where the local viceroyFootnote 138 welcomed him, just like others before, with great honours and the kindest regards. The viceroy treated him wonderfully for many days,Footnote 139 and when he [Ṣägga Krәstos] wished to go to Rome, the viceroy had him escorted by his lieutenant-general and Monseigneur Gafrarelly, archbishop of Saint Severin.Footnote 140