Background

Limb-loss as a consequence of military service has been thrust into the public consciousness and on to political agendas as a result of recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (Caddick and Smith Reference Caddick and Smith2014). The injuries produced by these conflicts have created a legacy that veterans and the societies they are part of will need to deal with for many years to come, throughout the lifecourse of limbless veterans (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Phillip, Bosanquet, Bull and Clasper2015; Geiling, Rosen and Edwards Reference Geiling, Rosen and Edwards2012). For example, a Congressional report from the United States of America (USA) revealed that 1,645 US veterans lost a limb during the US-led global war on terror,Footnote 1 whilst United Kingdom (UK) Defence Statistics indicated that 301 British veterans sustained an amputation through service in Iraq or Afghanistan.Footnote 2 The lifelong impact of traumatic limb-loss is also particularly relevant for older veterans who served in (among others) the Second World War, Korea, Northern Ireland, Vietnam and the Falklands, and whose health issues may be exacerbated by age-related changes and comorbidities, including the long-term psychological consequences of war (Geiling, Rosen and Edwards Reference Geiling, Rosen and Edwards2012; Hunt and Robbins Reference Hunt and Robbins2001).

The research literature on limb-loss in veterans has increased rapidly in volume as a result of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (e.g. Wool Reference Wool2015). Indeed, most of the studies have appeared post-9/11, indicating a renewed interest in this issue among researchers. This increasing interest dovetails with (and is partially derived from) the political imperative to care for veterans who lose limbs as a result of service. In the UK, the Armed Forces Covenant, which was enshrined in law in 2011, dictates that veterans and their families should not encounter disadvantage as a result of their service, and that where appropriate they should be entitled to special treatment (Ministry of Defence 2011). The Covenant explicitly states that those who have ‘given the most’ – including injured veterans – are to be given special consideration. Importantly, disadvantage experienced as a result of service may be taken to include the age-related after-effects of service-related injury and amputation (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Phillip, Bosanquet, Bull and Clasper2015).

Military personnel undergo amputations for a variety of reasons (Cifu Reference Cifu2010). Firstly, there are those whose injuries are ‘service attributable’, experienced as a result of combat or training accidents. These are the amputations for which military institutions are most directly accountable. Secondly, there are those who become injured whilst serving but ‘off-duty’, e.g. in motor vehicle accidents. Thirdly, some former personnel suffer chronic illness (such as diabetes) which results in amputation typically at ‘older’ ages (e.g. >50 years old). Whilst acknowledging an abundance of literature in this third area of older veterans who undergo amputations late in life (most of which appears to emanate from the US Veterans Administration (VA) health-care system; e.g. Kurichi et al. Reference Kurichi, Kwong, Vogel, Xie, Ripley and Bates2015; Littman et al. Reference Littman, Boyko, Thompson, Haselkorn, Sangeorzan and Arterburn2014), our focus in this systematic review is on the first group whose injuries are ‘service attributable’. It is this cohort which will have aged with limb-loss over many years and will have required significant health-care input throughout their lifetime (Geiling, Rosen and Edwards Reference Geiling, Rosen and Edwards2012).

Definition of terms

For the purpose of this review, the term ‘veteran’ refers to any former member of the Armed Forces who has served for more than a single day. This aligns with the UK government definition of a veteran, and is the most inclusive of any country. Whilst other countries’ definitions differ along the lines of deployment experience or length of service, the UK definition arguably provides the broadest scope for inclusion of research within our review. Some of the articles we reviewed did not state participants’ length of service, yet given the majority focused on traumatic limb-loss sustained on active duty, they were self-evidently longer-serving than the minimum required for ‘veteran’ status.

‘Limb-loss’ or ‘limbless’ refers to any individual who has undergone a ‘major’ amputation (i.e. above the level of ankle or wrist) (Kurichi et al. Reference Kurichi, Kwong, Reker, Bates, Marshall and Stineman2007). This may include those with multiple amputations (e.g. a bilateral lower-limb amputee) and those with amputations at different levels (e.g. above knee or below knee; AK/BK). In relation to veterans, this may include combat-related traumatic limb-loss (e.g. as a result of blast injury or damage from projectiles), injuries sustained in training accidents or those acquired during the course of normal duties. Given the terms ‘ageing’, ‘older’, ‘elderly’ and ‘later life’ are often used inconsistently or left undefined, following previous reviews (e.g. Cattan et al. Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005) we adopted any criteria used by the studies in this review.

Aims of the review

In this paper, we systematically review the literature on ageing and limb-loss in military veterans in order to (a) comment on the current state of knowledge regarding the long-term impact of limb-loss in veterans, (b) explore avenues for developing research in this area, and (c) highlight health and social care implications for older limbless veterans. Our aim is to extend the literature by providing a critical summary of the strengths, limitations, omissions and biases of current knowledge (Jesson and Lacey Reference Jesson and Lacey2006), thereby guiding future research in this area and stimulating informed policy reflection and decision-making.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

• Participants: older limbless military veterans. Excluded were younger (e.g. Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans). There were no restrictions on the type or cause of limb-loss, other than meeting the above definition of ‘major’ limb-loss and that the injury was sustained during the service person's military career.

• Comparators: where available, studies were included which drew explicit comparisons between ‘older’ (e.g. Vietnam-era) and ‘younger’ (e.g. Iraq/Afghanistan-era) veterans.

• Outcomes: long-term impact of limb-loss, health-care needs, and age-related complications or comorbidities associated with limb-loss. Excluded were studies focused solely on short-term rehabilitation.

• Study design: empirically based studies of any study design. Excluded were commentaries, reviews, etc.

For the purpose of this review, we wanted to include all studies relating to the long-term effects of limb-loss. Since the majority of service-related amputations happen to young military personnel in their mid-twenties (Geiling, Rosen and Edwards Reference Geiling, Rosen and Edwards2012), we included articles whereby participants were described as ‘middle-aged’ or older, thus ensuring that participants had been living with limb-loss for multiple decades at the time of study. For example, if ages were not stated explicitly, articles were included wherein date of publication or ‘time since amputation’ exceeded two decades from the end of the conflict in which participants were injured.

Search strategy

Guidelines for systematically searching and selecting papers for review were followed (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009). Key databases were searched including: ASSIA, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Medline, Web of Science, PsycArticles/PsychInfo, ProQuest Psychology and ProQuest Sociology Journals, and SPORTDiscus. The search terms included were as follows:

• ‘aging’ OR ‘ageing’ OR ‘older’ OR ‘elder*’ OR ‘later life’;

• ‘veteran’ OR ‘veterans’ OR ‘ex-military’ OR ‘ex-service’ OR ‘ex-force*’ OR ‘army’;

• ‘limbloss’ OR ‘limb-loss’ OR ‘limb loss’ OR ‘limbless’ OR ‘amput*’ OR ‘prosthe*’ OR ‘artificial limb’.

Given the large range of potential outcomes of interest, outcomes were not included in the search strategy. Rather, the above three search strings were used to capture all potentially relevant papers on older limbless veterans, with key outcomes highlighted during the initial phase of searching. Citation scanning was conducted for all papers included at the final stage. A special issue in the Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development – in which one of the searched-for articles was published – was searched, and the authors also searched their personal collections of articles.

Selection of studies, data extraction, quality assessment and synthesis of results

For screening, article titles and abstracts were scanned for relevance by one reviewer and checked against the inclusion criteria by five members of the review team and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. All relevant articles were subsequently read by three reviewers and a standardised data extraction form was used to record key findings from each study. This form was also used to capture details on the type of study, location and sample characteristics including age, gender, type/cause of amputation and (where relevant) conflict in which limb trauma originated.

Previous review studies (Bunn et al. Reference Bunn, Dickinson, Barnett-Page, Mcinnes and Horton2008; Cattan et al. Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Bungay, Munn-Giddings and Boyce2016) as well as recognised assessment tools (CASP 2013; EPHPP 2010) were used to guide processes of quality assessment. For qualitative studies, judgements were based on the suitability of the research design and recruitment processes for addressing the study's aims, the rigour of data collection and analysis processes, and whether there was a clear statement of the study's findings (CASP 2013). For the quantitative studies, quality was determined by an overall assessment of the appropriateness of the study design and methods in relation to the study's aims and objectives (Cattan et al. Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005). Studies were judged accordingly – by the same three reviewers who completed data extraction – as strong, moderate or weak according to their methodological quality, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

The research we identified was grouped into a number of ‘themes’ based on the content and focus of individual articles. These themes were identified and agreed upon by five reviewers at a meeting of the review team. The themes provided categories and sub-headings for organising the results and are as follows: (a) long-term health outcomes, prosthetics use and quality of life (QoL); (b) long-term psycho-social adaptation and coping with limb-loss; (c) disability and identity; and (d) estimating the long-term costs of care and prosthetic provision. Included papers were too heterogeneous (i.e. with regard to methodology, outcomes and focus of the studies) to attempt a meta-analysis. Following guidelines on producing systematic reviews (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2009) and previous review studies (Cattan et al. Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005), a narrative synthesis (as opposed to meta-analysis or other methods of integration) was therefore chosen as the most suitable means of synthesising findings from methodologically diverse studies.

Results

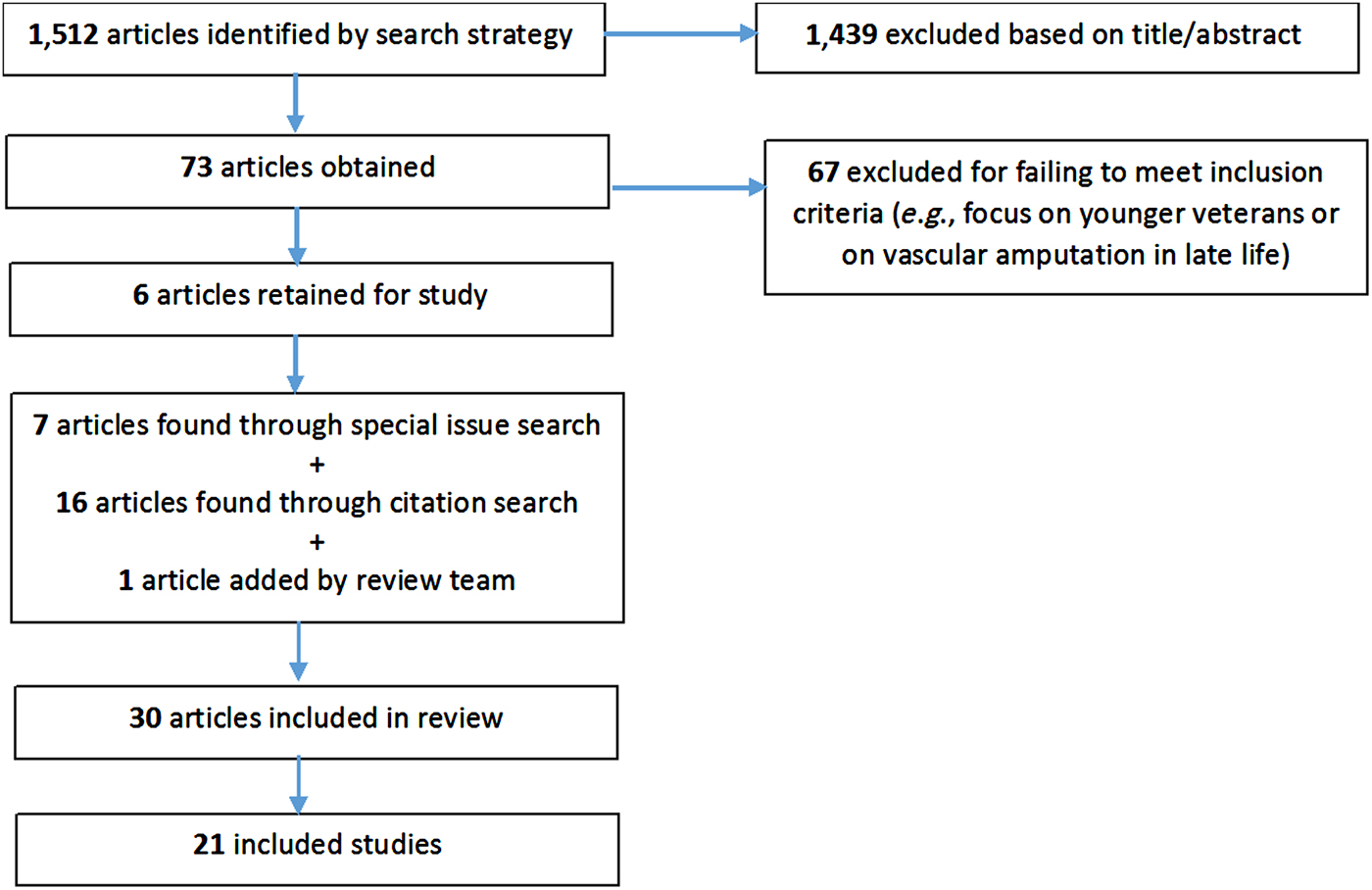

The search process yielded an initial 1,512 hits, which after screening resulted in a total of six articles relevant for inclusion (see Figure 1). Citation scanning resulted in an additional 16 articles. Given that many papers that were deemed relevant reported age and time since amputation of their samples, but did not refer to ‘ageing’, ‘older’ or ‘elderly’ veterans, a larger number of papers were identified through citation scanning than through the initial keyword search. Hand searching a special issue of Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development led to the discovery of an additional seven articles. The authors’ personal collections of articles yielded one further study.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of identification of eligible studies.

A total of 21 studies were identified, with one study – the VA's ‘Survey for Prosthetic Use’ (2010) – reported in ten separate articles (of which eight were published in a Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development special issue). Nine out of the 21 studies were conducted in the USA, with most of these (five of the nine) taking place within the VA health-care system. Four studies were conducted in Iran, one in Nicaragua and seven in the UK. Most studies (15 of the 21) were surveys of various long-term physical and psychological outcomes, three used qualitative or mixed methods (Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015; Machin and Williams Reference Machin and Williams1998; Meyers Reference Meyers2014) and three (Blough et al. Reference Blough, Hubbard, McFarland, Smith, Gambel and Reiber2010; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Phillip, Bosanquet, Bull and Clasper2015; Stewart and Jain Reference Stewart and Jain1999) used a form of economic modelling to estimate the long-term costs of caring for limbless veterans. The characteristics of all the studies are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Summary of papers from the Veterans Administration's (VA) ‘Survey for Prosthetic Use’ (2010) study

Notes: AK: above knee. BK: below knee. CTD: cumulative trauma disorder. OEF: Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). OIF: Operating Iraqi Freedom (Iraq). QoL: quality of life.

Table 2. Summary of the remaining studies included in the systematic review

Notes: 1. Study took place at US Veterans Administration. AK: above knee. BK: below knee. Blesma: British Limbless Ex-Servicemen's Association. CTD: cumulative trauma disorder. HRQoL: health-related quality of life. OEF: Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). OIF: Operating Iraqi Freedom (Iraq). PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder. QoL: quality of life. UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Long-term health outcomes, prosthetics use and quality of life

The largest collection of studies identified for review (16 of the 21) focused broadly on assessing long-term physical health outcomes (including pain and comorbidities) associated with limb-loss, levels of prosthetic utilisation by older limbless veterans, and the impact of health outcomes and prosthetic use on QoL. The largest of these studies was the VA's ‘Survey for Prosthetic Use’. This was a national survey comparing health outcomes, QoL and use of prosthetics among 298 Vietnam veterans with combat-related traumatic limb-loss (mean age = 61 years; time since amputation = 39 years) and 283 of their younger Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom (OIF/OEF) counterparts (mean age = 29; time since amputation = 3 years). It was noted that using prosthetic devices can improve functional ability, enhance mobility and safety, facilitate higher levels of activity, and can also reduce the risk of secondary comorbidities and problems resulting from overuse of intact limbs among limbless veterans (Gailey et al. Reference Gailey, McFarland, Cooper, Czerniecki, Gambel, Hubbard, Maynard, Smith, Raya and Reiber2010; Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010). The survey aimed to document differences in health status and device-use between older and younger veterans, and to forecast changes in the use of prosthetic devices. It used a combination of validated and bespoke measurement tools, as well as analysis of medical records data.

Overall, findings from the survey revealed that health status (as measured on the SF-36 health questionnaire) was reported as good, very good or excellent among 70.7 per cent of Vietnam veterans and 85.5 per cent of OIF/OEF veterans (Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010). Compared with OIF/OEF veterans, fewer of the older Vietnam veterans (90.5% versus 78.2%, respectively) were current prosthetic users (Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010). Findings on prosthetic use were further described with regard to the different types of amputation. Among lower-limb amputees, sole use of a wheelchair for mobility was more common in the Vietnam cohort compared with the OIF/OEF cohort, at 18 and 4 per cent, respectively (Laferrier et al. Reference Laferrier, McFarland, Boninger, Cooper and Reiber2010). Seventeen per cent of the Vietnam lower-limb amputees reported abandoning use of all prosthetic devices, rising to 33 per cent among bilateral lower-limb amputees, and 30 per cent among upper-limb amputees (Laferrier et al. Reference Laferrier, McFarland, Boninger, Cooper and Reiber2010; McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Hubbard-Winkler, Heinemann and Jones2010). Vietnam veterans reported more problems with their prosthetics and more pain when using them compared to OIF/OEF veterans (Berke et al. Reference Berke, Fergason, Milani, Hattingh, McDowell, Nguyen and Reiber2010). Other studies included in this review also revealed that prosthetic usage varied by type of amputation. For instance, a series of long-term follow-up studies of Vietnam veterans conducted by Dougherty (Reference Dougherty1999, Reference Dougherty2001, Reference Dougherty2003) revealed that 87.5 per cent of unilateral AK amputees were current prosthetic users (average of 13.5 hours per day) compared with just 22 per cent of bilateral AK amputees (average of 7.7 hours per day), thereby highlighting the significant additional impact of multiple compared to single limb-loss.

A high prevalence of comorbidities and pain was identified across the studies in this review. Most studies which assessed arthritis revealed prevalence rates of between 54 and 71 per cent among older limbless veterans (Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith and Reiber2014; Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015; Gailey et al. Reference Gailey, McFarland, Cooper, Czerniecki, Gambel, Hubbard, Maynard, Smith, Raya and Reiber2010; Kulkarni et al. Reference Kulkarni, Adams, Thomas and Silman1998; Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010), with one study of unilateral lower-limb amputees reporting a lower prevalence of 16.1 per cent (Norvell et al. Reference Norvell, Czerniecki, Reiber, Maynard, Pecoraro and Weiss2005). This compared with around 15 per cent of OIF/OEF veterans reporting arthritis (Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith, Esquenazi, Blake and Reiber2010). Three papers (Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith, Esquenazi, Blake and Reiber2010; Gailey et al. Reference Gailey, McFarland, Cooper, Czerniecki, Gambel, Hubbard, Maynard, Smith, Raya and Reiber2010; McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Hubbard-Winkler, Heinemann and Jones2010) reported a higher incidence of cumulative trauma disorder (CTD; overuse injuries resulting from reliance on the intact limb) among Vietnam veterans, which compromised their ability to use prosthetics and reduced their prosthetic satisfaction levels relative to younger veterans. Coincident with the ageing process and the occurrence of comorbidities, some Vietnam veterans’ prosthetics therefore became too heavy, uncomfortable and painful to use, resulting in more abandonment of prosthetics (Laferrier et al. Reference Laferrier, McFarland, Boninger, Cooper and Reiber2010).

Pain was reported as so prevalent among limbless veterans that it was often under-evaluated (Berke et al. Reference Berke, Fergason, Milani, Hattingh, McDowell, Nguyen and Reiber2010). Prevalence rates of numerous types of pain are described in Table 3. It was suggested by one study that phantom limb pain was often a persistent condition that stayed with the amputee for the remainder of life (Wartan et al. Reference Wartan, Hamann, Wedley and McColl1997). Another study described back pain and pain in contra-lateral (non-amputated) limbs as ‘disabling and progressive problems of long-term surviving amputees’ and argued that such problems were as great as phantom pains but were often overlooked (Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi Reference Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi2009: 1876). Eight papers reported the prevalence of mental health comorbidities among older limbless veterans (Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith, Esquenazi, Blake and Reiber2010, Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith and Reiber2014; Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi Reference Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi2009; Ebrahimzadeh and Hariri Reference Ebrahimzadeh and Hariri2009; Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015; Gailey et al. Reference Gailey, McFarland, Cooper, Czerniecki, Gambel, Hubbard, Maynard, Smith, Raya and Reiber2010; McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Hubbard-Winkler, Heinemann and Jones2010; Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010). These studies reported rates of depression between 9.7 and 28 per cent and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) between 15 and 46 per cent.

Table 3. Prevalence of pain among older limbless veterans

Despite the high prevalence of pain and comorbidities, QoL was reported as good, very good or excellent in 72.8–79.7 per cent of older limbless veterans (Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland Reference Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland2010; Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015). One reason for this may be that veterans tended to deal with pain via silent acceptance or a ‘stiff upper lip’ approach to coping (Machin and Williams Reference Machin and Williams1998). One study (Taghipour et al. Reference Taghipour, Moharamzad, Mafi, Amini, Naghizadeh, Soroush and Namavari2009) reported significantly poorer QoL among limbless veterans compared to population norms. Among the factors related to poor QoL, Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland (Reference Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland2010) revealed that poorer self-reported QoL was significantly associated (in both Vietnam and OIF/OEF veterans) with the need for assistance with activities of daily living. Such assistance was required by one-third of upper-limb amputees in both older and younger veterans (McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Hubbard-Winkler, Heinemann and Jones2010). Among bilateral lower-limb amputees, Dougherty et al. (Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith, Esquenazi, Blake and Reiber2010) noted that 33 per cent of Vietnam veterans (compared with just 6% of OIF/OEF veterans) could no longer walk. In addition, fewer Vietnam veterans were participating in ‘high-impact’ activities such as skiing and basketball, compared with the younger cohort (see also Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010). In the only study to include qualitative analysis of older veterans’ QoL experiences, Foote et al. (Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015) provided vivid descriptions of the effects of impairment and restrictions on activities caused by amputation and by not being able to walk long distances due to pain. Declining mobility with age was linked strongly to poorer QoL in the narrative of one veteran interviewed in the study by Foote et al.

Other factors related to poorer QoL included a higher number of comorbidities, higher levels of pain and mental health problems (Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith, Esquenazi, Blake and Reiber2010, Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith and Reiber2014; Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland Reference Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland2010; Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015; Hoaglund et al. Reference Hoaglund, Jergesen, Wilson, Lamoreux and Roberts1983; Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010). Several papers noted the impact of age-related changes, pain and declining mobility on veterans’ QoL (Dougherty Reference Dougherty2001; Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith, Esquenazi, Blake and Reiber2010; Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi Reference Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi2009; Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015), with mental health problems such as depression and PTSD – endured for many decades in some cases – described as among the biggest reasons for poor QoL among older limbless veterans (Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi Reference Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi2009; Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland Reference Epstein, Heinemann and McFarland2010; Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015).

Finally, several papers considered the long-term impact of limb-loss on employment and personal relationships (e.g. Dougherty Reference Dougherty1999, Reference Dougherty2001, Reference Dougherty2003; Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith, Esquenazi, Blake and Reiber2010, Reference Dougherty, McFarland, Smith and Reiber2014; Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015; Reiber et al. Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010). In a long-term follow-up of bilateral AK amputees from Vietnam, Dougherty found that 70 per cent of veterans were or had been employed outside the home since their injury. Reiber et al. (Reference Reiber, McFarland, Hubbard, Maynard, Blough, Gambel and Smith2010) similarly reported a 78.7 per cent current employment rate among Vietnam veterans. The vast majority of veterans were also married and had had children (Dougherty Reference Dougherty1999, Reference Dougherty2001, Reference Dougherty2003; Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi Reference Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi2009; Ebrahimzadeh et al. Reference Ebrahhimzadeh, Kachooei, Soroush, Hasankhani, Razi and Birjandinejad2013). Accordingly, Dougherty (Reference Dougherty1999) argued that Vietnam veterans had lived ‘relatively normal lives’ within the context of their physical limitations and that, contrary to media narratives, did not on the whole experience insurmountable emotional and physical scars. Indeed, Foote et al. (Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015) suggested that older Vietnam veterans with limb-loss had continued to make major life transitions and experienced positive QoL, but that problems with pain, physical ailments exacerbated by ageing and mental health problems could also adversely affect QoL, thus underscoring the importance of ongoing care and rehabilitation.

Psycho-social adaptation and coping in older limbless veterans

Three studies (Desmond Reference Desmond2007; Desmond and MacLachlan Reference Desmond and MacLachlan2006; Machin and Williams Reference Machin and Williams1998) discussed coping and psycho-social adaptation among older limbless veterans. Desmond and MacLachlan (Reference Desmond and MacLachlan2006) surveyed coping strategies and psycho-social adaptation with a sample of elderly lower-limb amputees (mean age = 74 years) who were members of the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen's Association (Blesma). The term ‘psycho-social adaptation’ was not defined in this paper but was described in relation to an individual's ability to adapt to a range of challenges, including impairments in physical functioning, prosthesis use, pain, changes in occupation, and alterations in body image and self-concept. The authors reported that problem solving and seeking social support were coping strategies associated with fewer depressive symptoms and greater psycho-social adaptation among older veteran amputees. Avoidant coping strategies (e.g. denial, alcohol use) were associated with poorer psycho-social adjustment, echoing wider findings about the maladaptive use of avoidant coping strategies in adaptation to disability. Greater time since amputation was also positively related to adjustment, with the average length of time being 42.6 years among the Blesma veterans.

In a separate study, Desmond (Reference Desmond2007) then explored coping and adjustment with upper-limb amputees from the Blesma cohort. In this study, psycho-social adjustment was conceptualised as ‘the absence of clinically elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression and evidence of positive adjustment to amputation and prosthesis use’ (Desmond Reference Desmond2007: 17). Findings broadly mirrored those of the earlier study, although the associations between seeking social support and adjustment were not evident. As Desmond argued, the findings of this and the previous study hold relevance for the care of older veterans, in particular the importance of promoting adaptive, problem-focused coping strategies designed to enhance long-term adjustment and QoL.

Machin and Williams (Reference Machin and Williams1998) also explored coping strategies in relation to phantom pains. They reported that veterans generally made little use of strategies such as problem solving or emotional support, preferring a ‘stiff upper lip’ approach to coping and a silent acceptance of pain. Many had also given up on medical assistance, making comments such as ‘I have had no success with treatments so far, so there is no point in even trying’ (Machin and Williams Reference Machin and Williams1998: 293).

Disability and Identity

One study by Meyers (Reference Meyers2014) focused on the identity politics of disability and amputation amongst middle-aged veterans of Nicaragua's civil war of the 1980s. Meyers’ qualitative study drew upon interviews and participant observations conducted with opposing sides of the conflict in order to understand how each side positioned themselves with regard to the broader category of ‘disability’. For the ex-Contra rebels (politically marginalised following their defeat by the Sandinista regime), adopting the social identity of ‘disabled’ became a means of arguing for equal rights and the protection of disability benefits. On the other hand, the Sandinistas under the ‘Organization of Disabled Revolutionaries’ (ORD) sought to distance themselves from ‘other’ disabled people, preferring to emphasise their privileged status as ‘war heroes’. Their amputations were symbols of valour, setting them apart from other disabled groups and protecting them from ‘stigmatised’ disabled identities. Sandinista veterans thereby adopted an ambiguous relationship to other disabled people: choosing to set themselves apart yet occasionally being compelled to identify with wider disability movements in order to gain access to benefits and resources.

Meyers’ findings showed that the political and military context in which veterans were injured was an important feature of their long-term adjustment to ‘disability’ and negotiations around personal and social identity. By highlighting matters of social identity, Meyers also situated the study of older veteran amputees within the wider literature on critical disability studies (e.g. Meekosha and Shuttleworth Reference Meekosha and Shuttleworth2009), with which the literature on older veterans has otherwise yet to engage. Indeed, one insight from Meyers’ paper – mirroring the perspective of disability scholars more broadly (Meekosha and Shuttleworth Reference Meekosha and Shuttleworth2009) – was that disabled and amputee veterans were not a homogenous group in terms of their social identities and experiences of disability, and that various ‘intersecting’ identities (particularly in relation to age, gender, race and combat-era) were important in understanding their lives.

Estimating the long-term cost of prosthetic provision for limbless veterans

In line with the aims of this systematic review to evaluate the long-term impact of limb-loss, three papers considered the long-term financial burden of prosthetic device provision required to meet veterans’ mobility needs (Blough et al. Reference Blough, Hubbard, McFarland, Smith, Gambel and Reiber2010; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Phillip, Bosanquet, Bull and Clasper2015; Stewart and Jain Reference Stewart and Jain1999). Using Markov model analysis, Blough et al. (Reference Blough, Hubbard, McFarland, Smith, Gambel and Reiber2010) projected the cost of prosthetic device provision for US veterans over five-year, ten-year, 20-year and lifetime periods. Using the ‘Survey for Prosthetic Use’ sample (see above), the authors contrasted the estimated lifetime cost of provision for Vietnam veterans compared with OIF/OEF veterans. Given the greater number – and greater technological advancement – of prosthetics used by OIF/OEF veterans, the cost of provision for the younger cohort was significantly higher than for the Vietnam cohort. Costs were also compared by type of amputation, with unilateral upper, unilateral lower, bilateral upper and multiple limb-loss forming separate categories for analysis. Given that lower-limb prostheses were typically more expensive and complex than upper limbs, costs were also highest in the ‘multiple limb-loss’ category, such that the lifetime projected costs of provision for a single Vietnam and OIF/OEF multiple-limb amputee were US $750,000 and $3.4 million, respectively. This compared with lifetime costs for a unilateral upper-limb amputee at US $300,000 for Vietnam and US $1.1 million for OIF/OEF. Blough et al. asserted that future costs of prosthetic provision could be manageable for the VA and for the Department of Defence, but that their estimates were ‘conservative’ because of potential outliers and the cost of future emerging technologies.

In a similar study with UK veterans, Edwards et al. (Reference Edwards, Phillip, Bosanquet, Bull and Clasper2015) argued for the imperative of long-term planning to meet the prosthetic and rehabilitative needs of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Using a simplified version of the Markov model of Blough et al. (Reference Blough, Hubbard, McFarland, Smith, Gambel and Reiber2010), Edwards et al. estimated that the long-term (40-year) cost of rehabilitation and prosthetic provision for the entire UK veteran cohort of Iraq and Afghanistan was £288 million (US $444 million) in 2015 currency. Prior to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, Stewart and Jain (Reference Stewart and Jain1999) conducted a retrospective cohort study based on 98 British amputee veterans from previous conflicts in order to produce an estimate of lifetime costs. Extrapolating from their sample to the rest of the UK population of war amputees, the figure they produced was £69 million, which did not account for any related, hidden or future costs and, according to the authors, was likely to be a significant under-calculation.

None of the cost-estimate studies were, however, able to account for variations in the cost of care provision through chronic disease, age-related changes (e.g. in mobility) and comorbidities such as mental health problems that limbless veterans are likely to encounter ‘downstream’ (Geiling, Rosen and Edwards Reference Geiling, Rosen and Edwards2012). As Geiling, Rosen and Edwards (Reference Geiling, Rosen and Edwards2012: 1237), in their commentary on the ‘medical costs of war in 2035’ put it, there was a need to consider the ‘secondary and tertiary consequences in middle age [which] might include decreased mobility, weight gain, coronary artery disease, and diabetes mellitus’. Accordingly, Geiling, Rosen and Edwards emphasised the need for early interventions – including prevention and treatment measures – to help mitigate the likely additional costs to society. Indeed, as Edwards et al. (Reference Edwards, Phillip, Bosanquet, Bull and Clasper2015: 2854) also cautioned, their estimates should be considered merely as ‘the start of a challenge to develop sustained rehabilitation and recovery funding and provision’, and that ongoing assessment of injured soldiers and their care would be required as the population ages.

Quality of the literature on ageing and limb-loss in veterans

The literature as a whole is over-reliant on the self-report survey method (17 of the 21 studies). Whilst many of these were large, well-designed surveys which included comparison groups, there are limitations associated with this dependence on survey methodology. For instance, 11 studies discussed the potential representativeness of their samples, including questions over the presence of selection bias and differences between respondents and non-respondents. In particular, evidence that some veterans self-medicated with alcohol to deal with phantom pain (Sherman, Sherman and Parker 1983) and avoided contact with clinicians when treatments were deemed ineffective (Machin and Williams Reference Machin and Williams1998), could indicate that non-respondents had potentially more severe problems with mental health or alcohol use. It could also be argued that the use of a single five-point scale to assess QoL within the VA ‘Survey for Prosthetic Use’ was an overly simplistic measure for a complex, multi-faceted construct. Whilst 11 studies used validated measurement instruments (12 also incorporated bespoke measurement tools), only one study (Kulkarni et al. Reference Kulkarni, Adams, Thomas and Silman1998) used medical assessments to determine the presence of comorbidities. There was also an absence of longitudinal follow-up studies which would have been able to determine the impact of limb-loss over time or throughout the lifecourse (Murrison Reference Murrison2011).

Of the studies based in full or part on qualitative methods (Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015; Machin and Williams Reference Machin and Williams1998; Meyers Reference Meyers2014), only one (Meyers Reference Meyers2014) provided sufficient information on data collection and analysis procedures for methodological rigour to be assessed. This study was classified as strong, based on the quality and extent of data collection, well-documented relationship between researcher and participants, clearly articulated findings and implications, and good grounding in theory. With the exception of this paper, however, the literature on older limbless veterans lacked theoretical depth and engagement with critical social issues such as ageing and disability, identity and independence (e.g. Schwanen and Ziegler Reference Schwanen and Ziegler2011). Overall, the quality of the literature on ageing and limb-loss in veterans may be categorised as weak-to-moderate. Despite an over-reliance on the self-report survey method, findings do appear consistent across the literature (see Tables 1 and 2), and the measures used possessed some face validity. Accordingly, the literature reviewed can be considered useful for drawing some conclusions regarding the long-term impact of limb-loss on veterans, whilst also recognising the need for further well-designed research studies (both quantitative and qualitative), and prospective, longitudinal studies.

Discussion

Summary of results

This systematic review makes a contribution to the existing literature on ageing and limb-loss in military veterans by analysing the results of numerous studies, and by identifying key factors associated with the long-term impact of limb-loss. We were also able to identify the strengths, limitations and omissions of this body of research. Key findings emphasise that, whilst limbless veterans are generally able to achieve a good QoL, limb-loss is still a progressive and degenerative injury involving enduring experiences of pain, comorbidities and sometimes mental health problems which undermine veterans’ health, wellbeing and QoL. Furthermore, it is evident that approaches to coping, as well social and political context, exert an important influence on veterans’ long-term adjustment and identity in relation to limb-loss. Finally, the literature highlights the substantial cost of caring for limbless veterans throughout the lifecourse and the financial commitments required to safeguard their long-term health and care needs.

Comparison to other literature

Only two prior reviews could be identified regarding the impact of limb-loss on veterans (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Ipsen, Doherty and Langberg2016; Robbins et al. Reference Robbins, Vreeman, Sothmann, Wilson and Oldridge2009). One review (Robbins et al. Reference Robbins, Vreeman, Sothmann, Wilson and Oldridge2009) focused on long-term health outcomes associated with war-related amputation, but was not systematically conducted and the focus was solely on clinical outcomes. The other (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Ipsen, Doherty and Langberg2016) was a systematic review of the physical and social factors determining health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for veterans with lower-limb amputation. Whilst some of the included studies focused on long-term impact, this was therefore limited to the outcome of HRQoL in lower-limb amputees. As such, the present study remains the only systematic review to have captured the long-term impact of limb-loss in older veterans across a broad range of outcomes and studies.

Whereas the studies on coping and psycho-social adaptation among older limbless veterans focused predominantly on the physical impact of limb-loss, exploration of the long-term psychological effects of traumatic injury has been largely overlooked. Indeed, other research indicates that the psychological consequences of war trauma can be very long lasting, and that those with a physical disability may experience even greater distress as their injuries become more disabling through ageing (Burnell, Coleman and Hunt Reference Burnell, Coleman and Hunt2010; Hunt and Robbins Reference Hunt and Robbins2001). It is unfortunate, therefore, that the literature on coping among older veterans shows a lack of engagement with the potential psychological consequences of traumatic limb-loss.

Within the wider literature on limb-loss (e.g. Heavey Reference Heavey2013; Wool Reference Wool2015) and ageing veterans (e.g. Burnell, Coleman and Hunt Reference Burnell, Coleman and Hunt2010; Hunt and Robbins Reference Hunt and Robbins2001), there are numerous studies which explore the narratives and experiences of ageing and disability. Such studies show how the stories people tell about their lives help them assign meaning to their experiences, and how these meanings are themselves derived from cultural narratives about ageing and disability (Phoenix, Smith and Sparkes Reference Phoenix, Smith and Sparkes2010; Smith and Sparkes Reference Smith and Sparkes2008). This topic is largely ignored, however, within the research we describe in this review. The omission of narrative research from the literature on older limbless veterans is significant, particularly when considered in light of a rich body of work in narrative gerontology (e.g. Kenyon, Bohlmeijer and Randall Reference Kenyon, Bohlmeijer and Randall2010) which attests to the value of stories both for understanding and improving the lives of individuals, and in a broader sense for understanding history from the perspective of those who lived through significant events. Accordingly, we suggest that research with older limbless veterans may productively adopt a narrative approach to understand better the lived experience of war and limb-loss throughout the lifecourse.

Strengths and limitations

This review is limited by the lack of a protocol published prior to carrying out the study. Whilst the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) checklist (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) was used during the write-up to ensure accuracy of reporting, the omission of a protocol from the study design limits transparency regarding any changes between protocol and systematic review. Furthermore, the limited quality of evidence in the studies reviewed inevitably restricts the conclusions that can be drawn, due in part to the questionable representativeness of some studies and the fact that the most isolated and severely disabled older veterans may not have been reached (Foote et al. Reference Foote, Kinnon, Robbins, Pessagno and Portner2015).

Strengths of this review include the broad inclusion criteria and wide search strategy which meant that a large number of diverse studies were able to be reviewed and synthesised. We were therefore able comprehensively to identify all relevant studies across a number of different domains, and were able to highlight consistent findings regarding the long-term impact of limb-loss on older veterans.

Implications for policy makers

One clear strength of the literature is that a wide range of age-related changes and comorbidities have been identified among older limbless veterans, as has the potential impact of these various conditions on independence, mobility, health and QoL. Amputation is not a static disability, but a ‘progressive deteriorating condition’ that affects the health status of amputees over time (Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi Reference Ebrahimzadeh and Fattahi2009: 1873). It is important to note, therefore, that age-related changes may complicate the process of long-term recovery and capacity for prosthetic use, with subsequent health-care implications for older veterans (McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Hubbard-Winkler, Heinemann and Jones2010). The findings of this systematic review indicate significant challenges regarding the long-term physical and mental health of limbless veterans. There is thus a compelling case to ensure that (very) long-term care requirements, including the cost of repairing and replacing prosthetic devices and of mental health care, are adequately considered when the future costs of care provision are estimated (Blough et al. Reference Blough, Hubbard, McFarland, Smith, Gambel and Reiber2010; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Phillip, Bosanquet, Bull and Clasper2015; Geiling, Rosen and Edwards Reference Geiling, Rosen and Edwards2012). In addition, given the majority of veterans were long-term prosthetic users, ensuring the continuation of health-care staff trained in advanced prosthetic technology will be necessary to meet future care needs and to maintain expertise in the absence of current military conflict (Blough et al. Reference Blough, Hubbard, McFarland, Smith, Gambel and Reiber2010).

Several US papers included in this review also noted the influence of a ‘paradigm shift’ concerning the goals and purpose of rehabilitation for limbless veterans (Berke et al. Reference Berke, Fergason, Milani, Hattingh, McDowell, Nguyen and Reiber2010; Gailey et al. Reference Gailey, McFarland, Cooper, Czerniecki, Gambel, Hubbard, Maynard, Smith, Raya and Reiber2010; Laferrier et al. Reference Laferrier, McFarland, Boninger, Cooper and Reiber2010; McFarland et al. Reference McFarland, Hubbard-Winkler, Heinemann and Jones2010). This shift was described in terms of providing veterans with the opportunity to return to active duty (should they wish to), with 18–21 per cent successfully returning at the time of the research compared to 2–7 per cent in previous eras (Laferrier et al. Reference Laferrier, McFarland, Boninger, Cooper and Reiber2010). In the UK, research by Dharm-Datta et al. (Reference Dharm-Datta, Etherington, Mistlin, Rees and Clasper2011) revealed that 63 per cent of a sample of 52 limbless veterans had returned to work in the services, with four veterans able to re-deploy to Iraq or Afghanistan. However, the implications of this ‘paradigm shift’ in rehabilitation were not discussed. For example, veterans are undergoing rehabilitation for limb-loss in militarised settings such as the Walter Reed Army Medical Centre (USA) and Headley Court (UK). Yet, it is unclear to what extent a military-style rehabilitation and a return to military life may prepare limbless veterans for independent living in the long term and a future civilian career post-service.

As part of the wider paradigm shift, Messinger (Reference Messinger2010) examined how a sports-based model of rehabilitation might prepare veterans for a future post-limb-loss. Messinger identified a dominant sports-based approach to rehabilitation in military settings, whereby returning to high-impact activities such as running, hiking, skiing and basketball was seen as symbolic of, if not constitutive of, recovery (Messinger Reference Messinger2010). In the case study of an Iraq War veteran amputee that Messinger presented, this model of rehabilitation – with its intense focus on the restoration of physical functioning – came into conflict with the veteran's own wishes and desires in terms of intellectual development and preparation for a future career beyond the military. The sports programme was ‘not elastic enough to encompass the alternative notions of rehabilitation and recovery’ held by the veteran himself (Messinger Reference Messinger2010: 299). More broadly, the use of sport for/as rehabilitation is epitomised in new initiatives such as the Invictus Games which offers an international, Olympic-style sporting competition for injured veterans. The narrative associated with such events centres on ‘battling back’ or ‘overcoming’ amputation through sport (Batts and Andrews Reference Batts and Andrews2011). Notwithstanding the benefits that such sporting events may bring to limbless veterans (for a review, see Caddick and Smith Reference Caddick and Smith2014), one question that has yet to be answered is what happens to these veterans after the events, when the limelight has disappeared and they begin to encounter the long-term challenges of limb-loss, as identified in this systematic review.

Implications for research

One limitation of the literature is that much of the knowledge is concentrated in the USA, and specifically on Vietnam veterans cared for within the VA health-care system. Given that different conflicts tend to produce different kinds of traumatic injuries (such as the increase in ‘polytraumatic’ injuries and traumatic brain injuries which Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are now surviving; Dharm-Datta et al. Reference Dharm-Datta, Etherington, Mistlin, Rees and Clasper2011), it is uncertain to what extent knowledge based on Vietnam veterans will generalise to the current generation of limbless veterans as they age. Furthermore, differences in the ways care is organised across different national and cultural contexts means that findings might not transfer easily outside the US context. In the USA, veterans’ health care is organised under the large, separately funded US Department of Veteran Affairs. By contrast, in other countries such as the UK, care for veterans is predominantly delivered by civilian providers and third-sector organisations. More specifically, within the UK once a serviceperson leaves the armed forces, the responsibility for care passes from the Ministry of Defence to the National Health Service (NHS). Invariably the NHS care for veterans is supplemented or supported by third-sector organisations such as Blesma, Help 4 Heroes, Combat Stress, etc. Academics and policy makers in the UK and elsewhere should therefore adopt a cautious approach to extrapolating from US findings, and should seek to expand the knowledge base on older limbless veterans in other national contexts.

There are further omissions from the literature. None of the papers in this systematic review considered the issue of social isolation as a potential long-term outcome associated with limb-loss in older veterans. This is despite the fact that social isolation has been identified as an important concern among older veterans (Ashcroft Reference Ashcroft2014) and among older amputees in general (Briggs Reference Briggs2006; Murray Reference Murray2005). Indeed, Murray (Reference Murray2005) suggested that reluctance to use a prosthetic limb may result in isolation among older amputees; a possibility that was not considered in the papers that dealt with prosthetic use. Additionally, the impact of traumatic limb-loss on families and social relationships was not explored in the studies reviewed. Yet, as Fossey and Hacker Hughes (Reference Fossey and Hacker Hughes2014) argued, the needs of family members – whilst poorly understood at present – should be taken into consideration as part of care planning and provision for limbless veterans. Future research with older limbless veterans should therefore consider the life-long impact of care-giving upon families, e.g. with regard to the financial and psychological impact of caring (Fossey and Hacker Hughes Reference Fossey and Hacker Hughes2014; Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Friedemann-Sanchez, Hall, Phelan and van Ryn2009).

Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the long-term impact of limb-loss in veterans and the associated need for ongoing rehabilitation and care throughout the lifecourse. The following recommendations are possible for researchers and policy makers. Firstly, it is important to understand the specific health-care needs of older veterans, and to deal with the multiple comorbidities and age-related changes they are likely to encounter as they move throughout the lifecourse. These are the secondary and tertiary consequences of limb-loss and must be considered as part of the traumatic legacy of combat injury. Secondly, researchers should seek to explore older veterans’ experiences of limb-loss in order to appreciate fully the long-term personal and social impact of amputation. The lives and experiences of family members should also form part of this research agenda. Thirdly, the issue of social isolation – reported to be a matter of concern among older amputees in general – should be given greater consideration in research with older limbless veterans. Finally, the clinical and academic interest in older limbless veterans in the US context should be mirrored by other countries, particularly as part of government commitments to support those injured by conflict.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding received from the Ministry of Defence Covenant Grants, as part of The Royal British Legion Aged Vetetans Fund portfolio. The authors also wish to acknowledge the constructive comments of two anonymous reviewers which helped to improve the manuscript prior to publication.