Introduction

Ageing is emerging as a key policy issue. One reason for this is that both the absolute number as well as the proportion of older people in populations around the world are increasing (World Health Organization, 2015). In Europe, the percentage of people aged 65 and over is increasing at an unprecedented rate and is expected to account for over 30 per cent of the population by 2060 (European Commission, 2015). Within the 28 countries of the European Union, approximately nine out of ten people aged 65 and over in Germany, France, Finland and the United Kingdom live independently in their own home. In the Netherlands, the percentage is even higher (95%). By contrast, Southern and Eastern European countries such as Cyprus, Spain, Portugal and Estonia show particularly low percentages. In these countries, older people more often live in common households together with their children. In Romania, Poland and the Baltic States more than 10 per cent of older people are in this type of living arrangement, which is only practised by 4.6 per cent of senior citizens Europe-wide. It is particularly rare in the Scandinavian countries and the United Kingdom (Eurostat, 2011). These trends affect national policy in all countries and have major implications for the allocation of national resources and budgets (International Federation of Ageing (IFA), 2011). Ageing is also strongly associated with the unpredictability of retirement costs and the costs of care (Van Nimwegen and Ekamper, Reference Van Nimwegen and Ekamper2018). Taken together with the fact that a further increase in life expectancy is inevitable, this massive demographic change calls for a major effort to ensure quality of life of the older population (Giacalone et al., Reference Giacalone, Wendin, Kremer, Frøst, Bredie, Olsson, Otto, Skjoldborg, Lindberg and Risvik2014). However, the increase in life expectancy may be viewed as a public health achievement, and older people are heterogeneous and many are continuing to help their families and friends even in their later years (IFA, 2011), which is beneficial for older people ‘ageing in place’. Additionally, Western countries have been experiencing similar patterns of change in their population due to cultural changes. Not only has life expectancy increased, but also marriage, fertility and birth rates have changed. Most couples have their first child at a higher age than previously, there are more divorces, common-law unions and out of wedlock births. These developments are also called the ‘Second Demographic Transition’ (Lesthaeghe, Reference Lesthaeghe2010) and have led not only to challenges concerning how older people can be supported, in remaining independent and active, but also how the quality of life in general can be improved.

As mentioned earlier, also Western societies are currently dealing with the rapid ageing of their population. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new concepts, programmes and services to fulfil the expectations of their older population, but also for the service providers and policy makers (Iecovich, Reference Iecovich2014). Askham, Cameron and Heywood (Reference Askham, Nelson, Tinker and Hancock1999) have studied the wishes and demands of older people concerning their living environment (Means, Reference Means2007). They found that older people's choice to stay in their home for as long as possible is especially influenced by policies, but also by their own individual needs. It appears that most older people are attached to their independence and that they prefer to live in the environment with which they are familiar (Machielse, Reference Machielse2016; Vermij, Reference Vermij2016). The main reason for this is that independent living contributes to maintaining a sense of self-reliance, self-management and self-esteem (Milligan, Reference Milligan2009). Machielse (Reference Machielse2016) endorses that older people should be able to live independently, provided that their health situation allows them to do so and that there is adequate housing and social support available in their own living environment.

In many countries, the question of whether or not older people continue living in their own house is strongly related to their financial situation, and how it fits with the costs of residential and nursing home provision (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shie, Wang and Yu2015). According to Horner and Boldy (Reference Horner and Boldy2008: 358), ‘‘ageing in place’ has the potential to provide more appropriate care at a lower cost than a move to a more specialised and sheltered facility’. ‘Ageing in place’ is mentioned as one possible solution to these financial issues. It may save financial expenditures and improve the quality of life of older people (IFA, 2011). The idea behind the policy of ‘ageing in place’ is that living in a familiar environment has a positive impact on the wellbeing of older people and contributes to positive experiences in later life (Van Dijk, Reference Van Dijk, Cramm, Van Exel and Nieboer2015).

Although a field of study about ageing, the needs of older people and the issues brought about by the fact that a large(r) part of society is 65 or over has taken shape over the past the last ten years, the concept ‘ageing in place’ is used very broadly and has not been defined very clearly so far.

The aim of this study is to identify conventions and patterns in the scholarly treatment of the concept of ‘ageing in place’. A more thorough understanding of ‘ageing in place’ might provide knowledge about the existing key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’ to allow professionals, governments, researchers and communities to attune their policies better. We therefore conducted a scoping review and formulated the following research question:

• How is ‘ageing in place’ defined in the literature and which key themes and aspects are described?

Methods

The overview was created using Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review. A scoping review is particularly useful for examining a broadly covered topic to map the literature comprehensively and systematically, and identify key concepts, theories, evidence or research gaps (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005). It also allows the inclusion of many different study designs, which suits the aim of giving an overview of the way researchers define ‘ageing in place’. Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review methodology outlines an approach consisting of six stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results, and (6) consultation.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

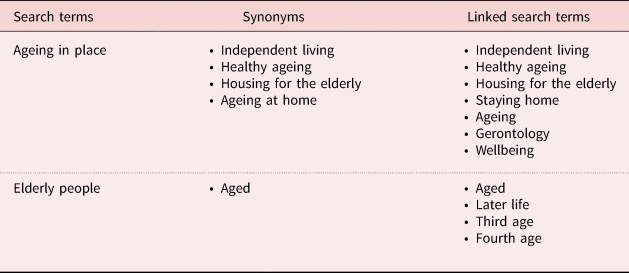

The starting point of this scoping review is the identification of the research question. Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) suggest using an iterative process for developing one or more guiding research questions. An exploratory literature study was conducted to increase the authors’ familiarity with the literature, so that a research question could be formulated. ‘Ageing in place’, ‘key themes’ and ‘aspects’ were identified as key words for the research question. ‘Ageing in place’ was operationalised in synonyms (independent living, healthy ageing, housing for elderly and ageing at home) and search terms by the findings of an initial search to become better acquainted with the literature. Key themes was defined as a collection of somewhat related values and aspects. ‘Aspects’ means the side from which something is considered.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

The eligibility criteria form the limitations to this research and the base of including or excluding resources. These limitations are strict guidelines and offer a framework in order to prevent the research from becoming too broad or even invalid. They also help the researchers (authors KEP-H and IZ) to stay on the same track, while analysing different resources. To set up the inclusion criteria we applied the Population, Concept and Context mnemonic method (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015). Based on the research objective and research question, we further defined and elaborated the inclusion criteria for the research population, the concept, the context and types of sources. The inclusion criteria used are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies on definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’

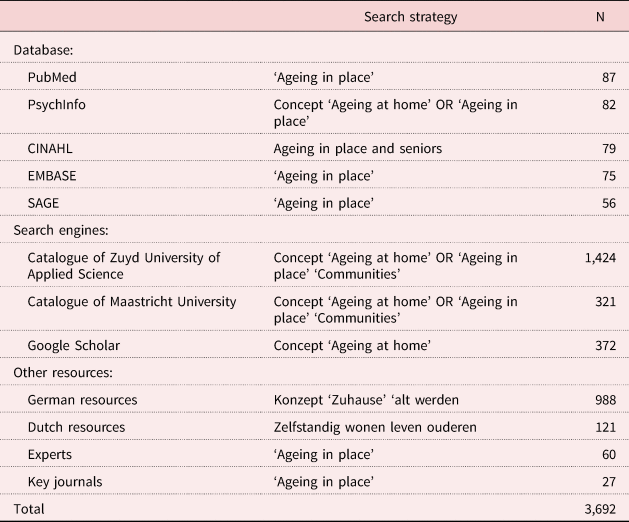

Five electronic databases (PubMed, PsychInfo, EMBASE, CINAHL and SAGE) were used to find the studies to be analysed for this scoping review. Additionally, three search engines (Google Scholar, and the catalogues of Maastricht University and of Zuyd University of Applied Sciences – both in the Netherlands) were used to optimise the search results of the electronic database searches and to improve the reliability of the search strategy (Bramer et al., Reference Bramer, Rethlefsen, Kleijnen and Franco2017). We conducted a search on 3 July 2019, with no restrictions on the date of publication. In addition, reference lists of relevant articles were screened to identify key studies that had been missed.

Research strategy

The research strategy comprises the choice of resources and the way to find those resources. The authors who reviewed the literature (authors KEP-H and IZ) first agreed on search terms. The selected search terms were combined and tested on the five electronic databases and three search engines. Bramer et al. (Reference Bramer, Rethlefsen, Kleijnen and Franco2017) argue that to reach a maximum recall, searches in systematic reviews ought to include a combination of databases and search terms. Combining the search terms led to a unique search strategy for each of the five electronic databases and each of the three search engines. For example, during our empirical testing, we decided to apply the search term ‘ageing at home’ to optimise the search results in the search engine Google Scholar. The results of the search terms that we ended up settling on for each database and search engines of the whole search strategy are available on request from the corresponding author. The search terms that the authors settled on and the search strategy are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2. Search terms of studies on definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’

Table 3. Search strategy of studies on definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’

Stage 3: Study selection

Once the searches (using the indicated search criteria) had been conducted, a selection had to be made from the results, so that actual analysis could take place. This study selection process was conducted on the basis of the inclusion criteria (Table 1), and consisted of three stages, each with a focus on a particular part of the studies (title, abstract and full text). During each of these three stages, the authors divided the studies into relevant, irrelevant and doubtful. Relevant studies are defined here as studies that fit the scope and objective of this scoping review. In order to validate the selection procedure, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were checked for consistency by the two reviewers (authors KEP-H and IZ) independently. This assessment was made first by looking at the title of the articles and then by looking at the abstract of each article. After screening the titles and abstracts, articles that were deemed eligible were obtained as full texts, further scanned for eligibility and finally discussed with the members of the Research Centre of Facility Management, Zuyd University of Applied Science for validation. The Research Centre of Facility Management consisted of experts in health care, facility management and research. For all studies that were excluded on the basis of their full-text articles, the reasons for exclusion were recorded in a logbook. The studies that were left after the third stage of selection were considered relevant for this scoping review. All articles that resulted from conducting the searches in the electronic databases and search engines were exported into Endnote X8, and registered in a logbook, making the part about comparing on the basis of consensus in each stage. If the researchers did not agree on the relevance of a study, a third reviewer (author GJJWB) was asked to decide on the suitability.

Stage 4: Charting the data

To facilitate the data selection, the researchers agreed to use a chart on which they noted all information that was considered useful. More specifically, they kept track of the following points: author(s), year of publication, country of origin, research aim, research question, study population, sample size, research methodology, definition the authors gave of ‘ageing in place’, key findings and conclusions.

Stage 5: Summarise and report

Focusing on definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’, we conducted a qualitative content analysis (Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010). An open axial coding method was used. The data from the articles were inductively coded in Excel. With open coding, labels were linked to the fragments from Stage 4 (charting the data). These labels summarised the core of the fragment. The labels were then analysed and the axial coding method was used to add overarching labels or themes. The analysis resulted in an overview of study characteristics, and an overview of main findings and definitions of ‘ageing in place’. Again, two reviewers (authors KEP-H and IZ) independently summarised and reported all results in tables. The content of the tables was then compared and adapted to consensus if necessary.

Stage 6: Consultation

The consultation stage consisted of two meetings with a focus group. In the first meeting, the validity of the research strategy was discussed. During the second meeting, the results of the research were presented and discussed. The focus group consisted of professionals (a housing corporation representative, a general practitioner, a community nurse, policy staff of health-care and welfare organisations, a local government employee), an older person and a member of a neighbourhood association. All of them, except the older person, assist older people while they ‘age in place’. The older person who is part of the focus group was asked to join to represent older people in this scoping review. This consultation phase provided opportunities for stakeholder involvement and provided insights beyond those in the literature.

Results

Study characteristics

Five electronic databases and three search engines were searched on 3 July 2019 with no restriction on the date of publication. Based on the first search, 3,692 articles concerning ‘ageing in place’ were identified. Next, 505 duplicate articles were removed. The titles of the remaining 3,187 articles were then reviewed, on the basis of which 339 articles were deemed suitable for the current study. Independent screenings were then conducted looking at the abstracts of these 339 articles, after which 59 articles were still considered relevant. A final assessment of these articles, this time taking the full text of each of them into account, left a final number of 34 relevant studies for the scoping review. An overview of the data selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the data selection process of the scoping review on ‘ageing in place’.

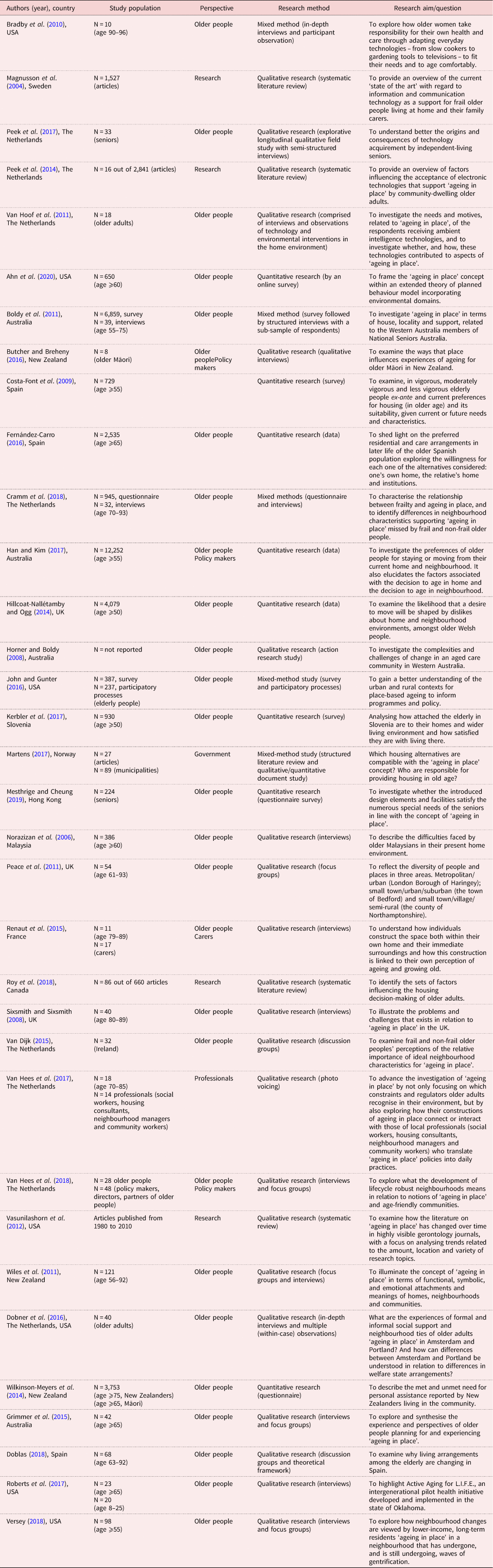

The reviewed articles focus on different geographical locations. Most of the studies concern European countries (N = 17), with the Netherlands (N = 8) and Spain (N = 3) being addressed most often, while seven studies each focus on Oceania (N = 7) and North America (i.e. the United States of America (N = 6) and Canada (N = 1)). Several different methodologies are used in the 34 selected studies, with the most common being qualitative research methodologies (N = 21), quantitative research methodologies (N = 8) and mixed methods (N = 5). The characteristics and research aims of the articles included in the current scoping review about ‘ageing in place’ are provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Descriptions of included research papers of scoping review on ‘ageing in place’

Notes: UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Definitions of ‘ageing in place’

Turning to the actual content of the selected studies, only two studies developed an explicit definition of ‘ageing in place’ as a result of empirical research. Most studies cited definitions from other sources, mostly in the introduction of their work. Although all these 34 included studies examined aspects related to ‘ageing in place’, none of them were directly focused on the development of a definition of this concept. Only two studies mentioned their own definition of ‘ageing in place’. Grimmer et al. (Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015) stated that ‘ageing in place’ is mostly about the opportunity for older people to remain in their own home for as long as possible, without having to move to a long-term care facility. Horner and Boldy (Reference Horner and Boldy2008: 356) defined ‘ageing in place’ as a ‘positive approach to meeting the needs of the older person, supporting them to live independently, or with some assistance, for as long as possible’.

Key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’

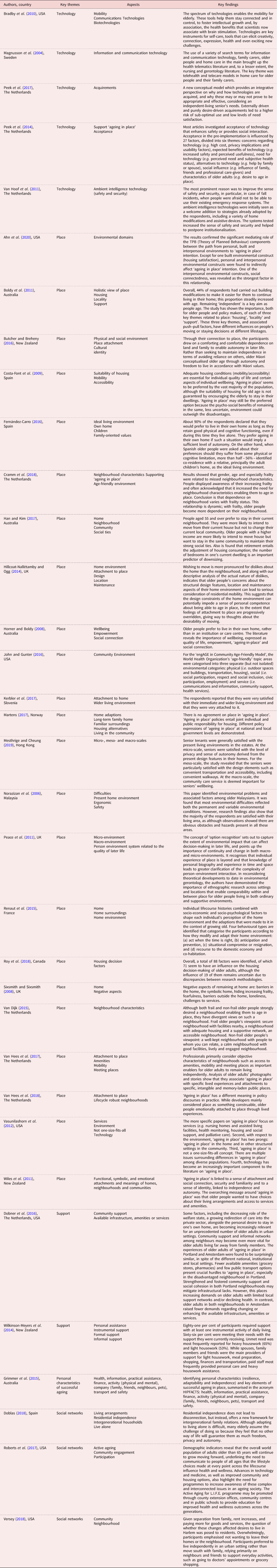

By structuring the data, the following key themes of ‘ageing in place’ were identified: place (N = 23), social networks (N = 2), support (N = 3), technology (N = 5) and personal characteristics of older people (N = 1). See Table 5 for the main findings of the included research papers.

Table 5. Main findings of included studies of scoping review on ‘ageing in place’

Notes: UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Place

Twenty-three out of the 34 studies focused on the key theme place. During the analysis of these 23 studies, a distinction between physical place and attachment to place was recognised. Some studies mentioned physical place, while others mentioned attachment to place.

Three levels of physical place are described, namely home, home environment and the neighbourhood. Studies that were focused on the physical home concern the choice between moving and making building modifications to make it easier for older people to continue living in their home (Boldy et al., Reference Boldy, Grenade, Lewin, Karol and Burton2011). Costa-Font et al. (Reference Costa-Font, Elvira and Mascarilla-Miró2009) argue that adequate housing conditions such as mobility and accessibility are essential for an individual's quality of life and certain aspects of individual wellbeing. Hillcoat-Nallétamby and Ogg (Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby and Ogg2014) argue that wishing to move is caused more by dislikes about the home than by the neighbourhood. The built environment has to be changed completely or adapted and improved for people to be physically able to age there (Martens, Reference Martens2017). The built environment is an important aspect among physical abilities. According to Sixsmith and Sixsmith (Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008: 227), increasing frailty and ‘barriers in and outside the home’ are examples of ‘physical health state’ and ‘the current state of the built environment’ having a huge impact on people's independence and thereby on their ability to age in place.

‘Ageing in place’ is also discussed in the sense of an attachment to place, as a place brings with it certain social connections, security, familiarity and a sense of identity (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2011). Three levels of attachment to place are described, namely home, home environment and the neighbourhood. As stated before, people normally wish to stay at home for as long as possible, they are quite attached to their home environment. Several theoretical approaches were analysed by Butcher and Breheny (Reference Butcher and Breheny2016) in order to find out what ‘attachment to place’ really means to older people. According to these authors, attachment to place combines social, environmental, functional, emotional and psychological meanings of place, and this attachment tends to increase over time (Butcher and Breheny, Reference Butcher and Breheny2016). Therefore, ‘ageing in place’ includes not only staying in one's own home, but also includes remaining in a stable and known environment where people feel that they belong. Responding to a description of attachment to place by Butcher and Breheny (Reference Butcher and Breheny2016), Van Hees et al. (Reference Van Hees, Horstman, Jansen and Ruwaard2017) recently used an approach where place is divided into socially related aspects and physical aspects. The social aspects refer to the place where people live with respect to emotions, memories, experiences and people, whereas the physical aspects are more related to the function and physical or hard elements of the place (Van Hees et al. Reference Van Hees, Horstman, Jansen and Ruwaard2017). Even though ‘ageing in place’ is mostly related to people ageing in their home, the place and environment they have been living in for a long time, there are several recent theories that redefine the term home in this context. In such theories, home does not only relate to places that people know but also to places that people are attached to emotionally and that allow them to live an individual and self-determined life outside an institutionalised environment (Bartlett and Carroll, Reference Bartlett and Carroll2011). This indicates that ‘ageing in place’ should not only be understood as people ageing in their own, known houses, but also as having the ability to move within their living environment (Han and Kim, Reference Han and Kim2017). This can either refer to the social environment, such as when people wish to live geographically closer to their social network, or to the built environment, such as when people move to a place where they can live a more self-determined and independent life. Butcher and Breheny (Reference Butcher and Breheny2016) argue that social environment and family are important. Older people with a higher income are more likely to intend to move from their house but want to stay in their current community to maintain their strong social ties (Han and Kim, Reference Han and Kim2017). Boldy et al. (Reference Boldy, Grenade, Lewin, Karol and Burton2011) argue that the place is a holistic concept consisting of three key themes: housing, locality and support. ‘Ageing in place’ is not a one-size-fits-all concept. There are multiple issues surrounding differences in ‘ageing in place’ among diverse populations (Vasunilashorn et al., Reference Vasunilashorn, Steinman, Liebig and Pynoos2012).

Summarising these findings, two interpretations of place can be derived from the literature. While the key theme place is used to refer to physical and functional aspects in some cases, it is used to describe much less tangible, rather emotional and experience-based aspects in other cases.

Social networks

Another way in which ‘ageing in place’ is viewed in the literature relates more to social networks. Only three out of the 34 studies focused especially on social networks. Doblas (Reference Doblas2018) focused on social networks in relation to living arrangements, residential independence and intergenerational households. More specifically, residential independence does not lead to disconnection with the social network, but instead, offers a new framework for intergenerational family relations. Although adapting to living alone is difficult, many older people assume the challenge of doing so because they feel that no other way of life will guarantee them as much freedom, privacy and autonomy. However, whatever the circumstances, the social actors (such as having strong emotional ties to their homes and environment) coincide in stating that they have regular family contact, practically daily with the children and/or other family members to whom they are closest. The relationship is face-to-face when relatives live nearby and, if they do not, the relationship takes place by telephone and in the form of occasional visits (Doblas, Reference Doblas2018). In her study concerning ‘ageing in place’ in Harlem, New York, Versey (Reference Versey2018) argues that there are also aspects to be careful about, when thinking of the consequences of ‘ageing in place’. Adjusting neighbourhoods and bringing diversity to communities may lead to separation from families, rent increases, and paying more for goods and services for the existing current residents of the neighbourhood. The participants of the Versey study stated that they were not willing to leave their current homes, even if it meant being separated from their families. They preferred living in their known urban setting and neighbourhood, being a member of the community and taking part in daily activities, relying on their neighbours and friends. The current residents and their wishes, also concerning their community, can be seen as an important aspect (Versey, Reference Versey2018). A study by Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Bishop, Ruppert-Stroescu, Clare, Hermann, Singh, Balasubramanan, Struckmeyer, Mihyun and Slevitch2017) concerns the importance of active ageing, community engagement and participation. They confirm that active ageing, community engagement, participation and social cohesion are important elements to engage older people to stay in contact with their social network. The next studies focused on social networks in combination with place or other key themes. As mentioned before, older people prefer to live in an environment (and surrounded by people) to whom they feel attached based on memories and experiences. The environment should be familiar, older people feel attached based on memories and experiences, as a familiar environment gives them a feeling of safety and security (Dobner et al., Reference Dobner, Musterd and Droogleever Fortuijn2016). This familiar environment can also be related to the social environment and to the people in the social network or community of older people. Older people mostly wish to be engaged and needed within their social network (John and Gunter, Reference John and Gunter2016). They want to be a part of the community and live a self-determined life. Joining the everyday life of the community leads to a maximisation of their self-fulfilment and enables older people to enjoy their lifestyle (Boldy et al., Reference Boldy, Grenade, Lewin, Karol and Burton2011). Joining the everyday life of the community also includes using the people's own individual talents to support the community. Engagement in the community is also important for people's mental health. Being a part of a community may help to prevent loneliness (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008). Overall then, although the theme ‘social networks’ is mentioned far less than the theme ‘place’ within the literature in the field, social networks are without doubt acknowledged as playing a part when it comes to ‘ageing in place’.

Support

Two studies focused on support as a key success factor for ‘ageing in place’. We found that two different kinds of support were brought up in the literature: formal support and informal support. Formal support is provided by professionals and service providers, while informal support is provided by informal networks consisting of anyone from family members, neighbours and friends, to the community in general. Formal support mainly consists of the infrastructure, facilities and services that are available to the older people in question, such as public transportation, grocery stores, pharmacies, meal services and personal care (Dobner et al., Reference Dobner, Musterd and Droogleever Fortuijn2016). Paid staff most frequently provide personal care and (heavy) housework assistance (Wilkinson-Meyers et al., Reference Wilkinson-Meyers, Brown, McLean and Kerse2014). Fewer available amenities (grocery stores, pharmacies) and few public transport options present crucial hurdles to ‘ageing in place’, especially in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Strengthened and fostered community support and social cohesion may mitigate infrastructural lacks. According to a study by Wilkinson-Meyers et al. (Reference Wilkinson-Meyers, Brown, McLean and Kerse2014), 81 per cent of the participants required support with at least one instrumental activity of daily living. Sixty-six per cent were meeting their needs with the support they were currently receiving. Unmet need was most frequently reported for heavy housework (65%) and light housework. The providers of informal support are family members, neighbours, friends and the community in general. They are the main providers of informal support, such as light housework, meal preparation, shopping, finances and transportation (Wilkinson-Meyers et al., Reference Wilkinson-Meyers, Brown, McLean and Kerse2014). According to Dobner et al. (Reference Dobner, Musterd and Droogleever Fortuijn2016), who focused on informal community support and informal networks among neighbours in their study, informal networks (friends, neighbours, community) may become even more vital for older adults who live far away from family members. Dobner et al. (Reference Dobner, Musterd and Droogleever Fortuijn2016) focused on informal community support and informal networks among neighbours.

Summarising these findings, support concerns personal assistance, the living environment, the daily needs and facilities, and is divided into formal support and informal support. Formal support is provided by professionals and service providers, while informal support is provided by informal networks made up of family members, neighbours, the community and friends.

Technology

Five out of the 34 studies defined ‘ageing in place’ in terms of technology. These five studies define technology as one or more of the following: support of mobility, information and communication technology (ICT), biotechnology and ambient intelligence. This spectrum of technology may enable older people to be more mobile. Bradby et al. (Reference Bradby, Joyce and Loe2010) stated that the spectrum of mobility technology is much broader than walking sticks, walkers, wheelchairs and stair lifts, and can include everything from automobiles to public transport, security systems, special shoes, clothing, medication and heaters. Older people incorporate a range of ICTs, including telephones, computers, televisions and radios, into self-care routines and meaningful activities. These tools not only help them stay connected and in control, but also help to foster intellectual growth and, as such, the health benefits that scientists now associate with brain stimulation (Bradby et al., Reference Bradby, Joyce and Loe2010). Biotechnology, such as pharmaceuticals and over-the-counter medications, are generally associated with health and wellbeing. However, paying attention to the meaning older people attach to medical use and non-use can illuminate how these biotechnologies are positioned as an array of techniques older people use to practise self-care (Bradby et al., Reference Bradby, Joyce and Loe2010). The ambient intelligence technologies were seen as a welcome addition to strategies already adopted by older people, including a variety of home modifications and assistive devices (Van Hoof et al., Reference Van Hoof, Kort, Rutten and Duijnstee2011). Older people have various motives to use ambient intelligence technologies to support ‘ageing in place’. The most prominent reason was that using these technologies improved the sense of safety and security that they experience, in particular when it comes to fall incidents. The fear of not being able to use existing emergency response systems in case of such incidents was mitigated by several of such ambient technologies and helped postpone institutionalisation (Van Hoof et al., Reference Van Hoof, Kort, Rutten and Duijnstee2011). Peek et al. (Reference Peek, Luijkx, Vrijhoef, Nieboer, Aarts, van der Voort, Rijnaard and Wouters2017) investigated the extent to which older people accept technology and which factors influence this acceptance rate. They found 27 factors which they divided into six themes: concerns regarding technology, expected benefits of technology, need for technology (e.g. perceived need and subjective health status), alternatives to technology, social influence (e.g. influence of family, friends and professional care-givers) and characteristics of older adults (e.g. desire to age in place). Peek et al. (Reference Peek, Luijkx, Vrijhoef, Nieboer, Aarts, van der Voort, Rijnaard and Wouters2017) also conducted a study about why and how technologies are acquired by older people and found that externally driven and purely desire-driven acquirements led to a higher risk of sub-optimal use and to low levels of need satisfaction.

In summary, it can be said that technology is a theme of significance when it comes to ‘ageing in place’, and that it covers a wide range of attributes and tools. Using technology may enable older people to live independently at home and may give them a feeling of safety and security.

Personal characteristics

Only one study focused on ‘ageing in place’ in relation to personal characteristics of older people. This study presented older people's views about how they and their peers perceive, characterise and address changes in their capacity to live independently and safely in the community. The authors identified personal characteristics (resilience, adaptability and independence) and key elements of successful ‘ageing in place’, summarised in the acronym HIPFACTS: health, information, practical assistance, finance, activity (physical and mental), company (family, friends, neighbours, pets), transport and safety. Supporting older people's choices to live safely and independently in the community (‘ageing in place’) can maximise their quality of life. Little is known of the views of older people about the ‘ageing in place’ process, and how they deal with the fact that they require support to live in the community accommodation of their choice, as well as how they deal with prioritising their choice (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015). This provided a range of insights about, and strategies for, ‘ageing in place’. Participants identified relatively simple, low-cost and effective supports to enable them to adapt to change, while retaining independence and resilience. The findings highlighted that successful ‘ageing in place’ requires integrated, responsive and accessible services. Key personal characteristics of successful ‘ageing in place’ are being resilient, having adaptability, and being independent, physically and mentally active, and healthy (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015).

Consultation

After consulting the focus group (Stage 6 in the Methods), the experts agreed with the overview of how ‘ageing in place’ is framed in existing literature. During the focus group meeting, the study characteristics, definitions, key themes and aspects were presented to the members of the focus group, after which a discussion took place about the results. The members of the focus group recognised and indicated the results found. Additionally, they indicated that one important aspect was not brought forward by the current study, namely the idea that ‘ageing in place’ should be primarily a long-term solution. According to the members of the focus group, definitions of the concept ‘ageing in place’ should make mention of long-lasting, durable solutions that allow and support older people to continue living at home, instead of temporary ad hoc solutions. The inclusion of durable solutions should be taken into account in the development of sustainable policies by both government(s), as well as health-care and service providers, where the quality of life and the wellbeing of older people are paramount.

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to identify conventions and patterns in the scholarly treatment of ‘ageing in place’. The findings of this study, resulting from an analysis of a total of 34 studies, highlight some key themes (place, social networks, support, technology and personal characteristics) that are largely congruent with the concepts and meanings of ‘ageing in place’ found in prior research. The majority of the studies that were analysed in the current review focused on aspects related to the key theme place. Two interpretations of place can be distinguished within these 23 studies: while some studies concentrate purely on the physical, functional aspects of place, others describe place in a more psychological way. The latter also has implications for the concept of ‘ageing in place’, because it does not bind people to one specific geographical place anymore but is more flexible and related to social ties. Another key theme of ‘ageing in place’ is social networks. Although the theme ‘social networks’ is mentioned far less than the theme ‘place’ within the literature in the field, social networks are without doubt acknowledged as playing a part when it comes to ‘ageing in place’.

The third key theme is support. Two different aspects of this theme were noticed, namely receiving support and offering support. Two studies relate to the support and assistance that older people receive from policy makers, service providers and the social network. Without this support many people would not be able to ‘age in place’. The fourth key theme is related to technology. The five studies that address this theme define the term technology as encompassing one or more of the following: support of mobility, ICT, biotechnology and ambient intelligence. Technology is a broad concept. Using technology may enable older people to live independently at home. Only one article (out of the 34) looked into personal characteristics of ‘ageing in place’. This article brought forward five key personal characteristics of ‘ageing in place’, namely resilience, adaptability, independence, physical and mental activity, and health.

To gain an insight into the interrelations among the key themes and aspects, we may look at geographical differences, the development of the concept ‘ageing in place’ over time, and the relation between different socio-economic, cultural backgrounds and different abilities of older people. We noticed some differences between studies from different continents in terms of the key themes that were mentioned. European studies pay most attention to the two key themes technology and place. Research into the key theme place is also being done in Oceania. The other key themes (social networks, support and personal characteristics) are highlighted across European countries, North America and Oceania. Not all regions cover all the five key themes. This brings a potential risk of lacking attention to one or more themes in those regions which might imply a threat for successful ‘ageing in place’. Our recommendation is to make sure that research on ‘ageing in place’ is conducted in such a way that the focus of conducted studies is distributed in a more balanced way, with each of the five key themes (and the coherence between them) being studied in all geographical regions. The evaluation of an experiment in Rotterdam in the Netherlands shows that this recommendation for an integrated approach of all key themes is valid. The experiment, ‘Even Buurten’, was part of the National Programme for Elderly Care in the Netherlands (2008–2016) and aimed to support the formal and informal networks around older people so that they can continue to live independently at home for as long as possible (Van Dijk, Reference Van Dijk, Cramm, Van Exel and Nieboer2015). The focus of this experiment was on social networks, support, self-reliance (personal characteristics) and the physical environment (place). Technology, supporting ‘ageing in place’ and attachment to place were not included in this integrated approach, although they are found to be related with ‘ageing in place’.

In addition to geographical differences in how research themes are addressed, we also noted differences over time. Vasunilashorn et al. (Reference Vasunilashorn, Steinman, Liebig and Pynoos2012) reported that topics related to the environment and services were the most commonly examined between 2000 and 2010, while the number of studies pertaining to technology and health/functioning was on the rise. According to Vasunilashorn et al. (Reference Vasunilashorn, Steinman, Liebig and Pynoos2012), this underscores the increase in diversity of topics that surround the literature on ‘ageing in place’ in gerontological research. Our study also shows a development over time with regard to the key themes. The studies related to technology were conducted between 2004 and 2017, those on place between 2006 and 2019, those on support between 2014 and 2016, those on personal characteristics in 2015, and those on social networks in 2017 and 2018. The key theme place is dominant in the evolution of the concept and has appeared more frequently as of late. In other words, a shift is noticeable: from ‘hard’ aspects of ‘ageing in place’ (place and technology) to ‘soft’ aspects (social networks and support).

The context of ‘ageing in place’ is diverse for older people, depending on their different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds and different abilities. Differences in socio-economic status have been operationalised by Grimmer et al. (Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015) in a so-called HIPFACTS score (health, information, practical assistance, finance, activity (physical and mental), company (family, friends, neighbours, pets), transport and safety; Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015). Lower HIPFACTS scores indicate a modest self-reliance. Modest self-reliance is not found to be beneficial for successful ‘ageing in place’.

Due to the scope of our study, we cannot do without a discussion about definitions of ‘ageing in place’ that the literature provides. Only two definitions of ‘ageing in place’ were found in the studies we analysed. We compared these definitions to the definition of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and came to the conclusion that all three definitions have been drawn up from another perspective. The CDC (2019) defined ‘ageing in place’ as ‘the ability to live in one's own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level’. This definition is particularly based on the ability older persons have or not. Horner and Boldy (Reference Horner and Boldy2008) defined ‘ageing in place’ more positively as the extent to which the needs of older persons are met, supporting them to live independently, or with some assistance, for as long as possible. The core of this definition is that support has to meet the needs of older people. Grimmer et al. (Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015) stated that ‘ageing in place’ is mostly about the opportunity for older people to remain in their own home for as long as possible, without having to move to a long-term care facility. This somewhat more narrow definition describes the situation as such. The three perspectives emphasise different components that may be complementary to each other.

Strengths and limitations

Our review has several strengths. First, we used a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases and search engines with no date restrictions, minimising the risk of having missed scientific studies about ‘ageing in place’. Second, to enhance trustworthiness, the process of selecting studies and extracting charting data was done independently, by two reviewers (Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010). However, the search that was conducted for this study may have also been subject to certain limitations. First, in our search we used a combination of keywords, but ‘ageing in place’ is a broad concept encompassing a varied terminology. It is possible that we have missed studies that used other terms with similar meanings. In an attempt to limit the effect of this issue, we checked reference lists and asked experts for literature. Second, we limited our search to databases of peer-reviewed, scientific articles. Books, grey literature and discussion papers, for instance, are not included. As a result, we may have missed some definitions of ‘ageing in place’. However, we were especially interested in the way ‘ageing in place’ is defined in the scientific literature, and we did not expect to find this within books and grey literature. Another problem we faced was that scientific publications frequently focus on just one key theme of ‘ageing in place’, such as place, social networks, support, technology or personal characteristics. It is therefore possible that our overview of key themes and aspects is incomplete and also that more authors than we found used their definition of ‘ageing in place’. We attempted to minimise this risk by checking the references for other sources providing more detailed descriptions. In future studies, it might be worthwhile to actively approach the authors of the included studies for additional information. A final remark is that we did not assess the quality of the selected studies. However, according to Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010), the strength of the scoping review methodology is that it focuses on the state of research activity rather than evaluating the quality of existing literature.

Conclusion and implications

The research question of this study was: ‘How is “ageing in place” defined in the literature and which key themes and aspects are described?’ ‘Ageing in place’ as a result based on empirical research is defined just in a very few studies. Grimmer et al. (Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015) stated that ‘ageing in place’ is mostly about the opportunity for older people to remain in their own home for as long as possible, without having to move to a long-term care facility. Horner and Boldy (Reference Horner and Boldy2008: 358) defined ‘ageing in place’ as a ‘positive approach to meeting the needs of the older person, supporting them to live independently, or with some assistance, for as long as possible’. From our scoping review, we noticed that the concept ‘ageing in place’ is broad. We were able to identify five key themes: place, social networks, support, technology and personal characteristics. Professionals and governments should consider including all of these key themes in the development of policies concerning ‘ageing in place’. Only then can they handle ‘ageing in place’ in an integrated way and develop policies that suit older people. Only five out of the 34 included studies focused on social networks (three) and support for older people (two). However, it is assumed that particularly social networks and support have a large impact on ‘ageing in place’. Further research into the relationship between ‘ageing in place’ and communities providing informal support is recommended. Future research on ‘ageing in place’ will face some serious challenges, such as longitudinal effects, changing populations and shifting health-care policies. There is only one way to deal with these challenges: keep focusing on the quality of life as it is perceived by older people who are ageing in place, because that aim will probably survive some generations.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by Maastricht University and Zuyd University of Applied Science in the form of sponsoring in time and manpower. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.