Introduction

With improvements in living conditions and better access to health care, an increasing proportion of the population is living longer around the world. However, living longer does not necessarily mean living better, e.g. in better health or happier (Solé-Auró and Alcañiz, Reference Solé-Auró and Alcañiz2015). In ageing societies, it becomes crucial to identify the conditions that guarantee that people age well.

Against this background, our paper aims to better understand whether people who are conventionally considered old, according to a traditional definition of old age set at age 65 (United Nations, 2001), actually feel old and if so which events or statuses they associate with such a feeling.

Today's ageing population is increasingly heterogeneous in terms of personal experiences of health and economic conditions (Robert et al., Reference Robert, Cherepanov, Palta, Dunham, Feeny and Fryback2009; Lowsky et al., Reference Lowsky, Olshansky, Bhattacharya and Goldman2014). Progresses in terms of longevity, healthy ageing and technological innovation have shaped today's older people as a generation that actively contributes to both society and family. Defining old age in a static and homogeneous way may therefore be meaningless. Alternative measures such as prospective age (Sanderson and Scherbov, Reference Sanderson and Scherbov2008; Scherbov and Sanderson, Reference Scherbov and Sanderson2016) allow ‘conceptualizing the paradox that ageing societies … may nevertheless grow younger at the same time, if residual life expectancy at median age rises despite a simultaneous increase in the median age’ (Marin and Zaidi, Reference Marin, Zaidi, Marin and Zaidi2007: 69).

In this respect, subjective measures based on individual perceptions of ageing and old age like those that we examine in this paper (e.g. Barak and Gould, Reference Barak and Gould1985) become fundamental in the reframing of old age. Indeed, they describe a more personal point of view on ageing that incorporates an individual's psychological sense of ageing within the immediate socio-cultural context (Westerhof and Wurm, Reference Westerhof and Wurm2015).

The importance of considering subjective measures of ageing is also testified by studies that showed their impact on subsequent health outcomes and survival, even after accounting for chronological age and past health conditions and behaviours. Despite the limited empirical analysis about ways in which subjective perceptions of age and ageing impact on individuals’ ability to age actively, works setting out the Risks of Ageism Model (e.g. Swift et al., Reference Swift, Abrams, Lamont and Drury2017) hint at a central role of attitudes towards age in affecting the recognised determinants of active ageing. In particular, it has been found that subjective evaluations of the own ageing process have direct implications for wellbeing (Westerhof and Barrett, Reference Westerhof and Barrett2005) and survival (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002): not feeling old may lead to better health and quality of life (e.g. Penninx et al., Reference Penninx, Guralnik, Bandeen-Roche, Kasper, Simonsick, Ferrucci and Fried2000), which in turn affect older people's involvement in society, family and the labour market. Thus, examining if people traditionally considered as old do feel old and when they do so is of crucial importance.

In this paper we therefore investigate feeling old among people aged 65–74 (i.e. whether they feel old). We have the opportunity, for the first time to our knowledge, to additionally study the aspects, events or roles that a person relates to feeling old. We also consider whether individuals perceive that they are considered old by society, independently of whether they report feeling old. We do so using a unique dataset, representative of the Italian population aged 65–74. This age group sets at the ‘turning point’ after which people are usually defined as old. The focus on Italy is of particular interest because the rapid and intense decline in fertility, together with the achievements in extending survival especially at older ages, have contributed to making Italy one of the countries with the highest median age in Europe.

This article adds to the literature in three ways: (a) by focusing on a quite homogeneous sample in terms of age which is likely to have similar life experiences and is still representative of the Italian population in that age group; (b) by using direct information about which events people associate with feeling old; and (c) by considering gender and educational differences in both the likelihood to feel old and its associated aspects.

In the next section, we review the relevant literature on age identity and describe the Italian context. The following section presents data and methods of analysis. We then show the results and discuss them in the concluding section.

Background

Ageing and age identity

The traditional understanding of old age as defined by the chronological age of 60 or 65 has been so much socialised that the individual perceived beginning of old age resembles it and does not even vary much across Europe, ranging from 59 in the United Kingdom (UK) to 68 in Greece (Ayalon et al., Reference Ayalon, Doron, Bodner and Inbar2014). However, chronological age is a too crude measure of ageing as it is an ascriptive characteristic (Barak and Rahtz, Reference Barak and Rahtz1999) that, as such, does not account for time and place. Thus, it ignores improvements in health and life expectancy that influence how people age (Lutz et al. Reference Lutz, Goujon, Wils, Fürnkranz-Prskawetz, Bloom and Lutz2008; Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Doblhammer, Rau and Vaupel2009; Sanderson and Scherbov Reference Sanderson and Scherbov2008, Reference Sanderson and Scherbov2013).

In the effort to define what ageing well means without drawing merely on chronological age, and at the same time allowing for inter-individual variation, it has been advocated that augmenting objective components with subjective ones would provide a more holistic conceptualisation of ageing (see e.g. Pruchno et al., Reference Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, Rose and Cartwright2010). Individual perceptions of ageing and ageing-related expectations, goals and actions may differ across individuals, even at the same chronological age (see e.g. Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Wahl, Brothers and Miche2015).

Research on the subjective dimension of ageing employed a series of notions that can be grouped under the umbrella concept of age identity (see e.g. Levy et al., Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002; Ayalon et al., Reference Ayalon, Doron, Bodner and Inbar2014; Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Wahl, Brothers and Miche2015; Kotter-Grühn, Reference Kotter-Grühn2015; Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Sutin, Caudroit and Terracciano2016; Bodner et al., Reference Bodner, Ayalon, Avidor and Palgi2017), such as feeling old – whether a person feels old; subjective age – how old a person feels to be; perceived old age – at which age a person thinks old age starts; and self-perception of ageing, which measures individuals’ assessment of their own ageing (e.g. Levy et al., Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002; Kaufman and Elder, Reference Kaufman and Elder2003).

Since the first conceptualisations of age identity, the single item on subjective age has mainly been the focus of analysis (Barak and Stern, Reference Barak and Stern1986; Barak, Reference Barak1987; Westerhof and Wurm, Reference Westerhof and Wurm2015). This was possibly because most of the available surveys on older people did not collect direct information on whether and when people feel old. Yet, all these concepts have been found to represent the unidimensional self-evaluation of how a person perceives their own ageing process. One's evaluation of their own present status against one's representations of age and ageing forms one's personal ageing model (Demakakos et al., Reference Demakakos, Gjonca and Nazroo2007). Therefore, although this paper focuses on feeling old and on the events that might have made people feel old, in the following we draw on insights also from the related literature on other measures of age identity for which more empirical evidence is available. As pointed out by Barak and Rahtz (Reference Barak and Rahtz1999), research on the subjective dimension of ageing has rarely sought to determine how ‘youthful’ or how ‘old’ people feel.

Research has found that after early adulthood most people feel younger than their chronological age (Barak and Stern, Reference Barak and Stern1986; Montepare and Lachman, Reference Montepare and Lachman1989; Rubin and Berntsen, Reference Rubin and Berntsen2006), in a sense distinguishing their psychological age from the age associated with one's physical appearance (i.e. when looking in the mirror). Barak and Stern (Reference Barak and Stern1986) indicated four groups of potential correlates of subjective age: (a) biological and physiological correlates (i.e. objective health status or self-perceived health); (b) demographic correlates (i.e. gender, marital status, socio-economic status); (c) social psychological correlates (i.e. life satisfaction, emotional health, morale); and (d) behavioural correlates (i.e. consumer behaviour, leisure-time activities). Indeed, subjective perceptions of age and ageing are likely influenced by age-related social categorisations that exist in society (Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Wahl, Brothers and Miche2015), but are also grounded in individuals’ experience of age-symbolic events, such as retirement and widowhood (Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al., Reference Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, Kotter-Grühn and Smith2008; Settersten et al., Reference Settersten, Richard and Hagestad2015) as well as grandparenthood and provision of grandparental child care (Bordone and Arpino, Reference Bordone and Arpino2016).

We should note that subjective age is different from feeling old in that the first concept informs us about the specific age with which a person identifies. This may actually reflect identification with a specific cohort. The feeling old concept rather ‘relates to the notion that one sees oneself as either closer to, or more distant from, the fountain of youth’ (Barak and Rahtz, Reference Barak and Rahtz1999: 233). However, the ‘ageless self’ notion (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman1986), suggesting that the discrepancy between subjective age (i.e. how old a person feels) and chronological age may be a byproduct of denial of ageing and the stigma associated with being an old person (Montepare and Lachman, Reference Montepare and Lachman1989), could be extended to the (not) feeling old concept.

It is also important to recognise the clear intuitive appeal of the concept of feeling old that allows individuals to judge themselves ‘on a true internal psychological assessment while at the same time using their evaluations of a full range of externalities to temper that judgment’ (Barak and Rahtz, Reference Barak and Rahtz1999: 249).

Gender, education and feeling old

Kornadt et al. (Reference Kornadt, Voss and Rothermund2013) referred to different life domains as being related to age stereotypes of men and women. Empirical evidence on the role of gender in affecting the subjective perception of age and ageing is, however, mixed. Barak and Rahtz (Reference Barak and Rahtz1999) found that neither subjective age nor likelihood of feeling older differed significantly between men and women. Other studies found gender differences in the association between life events and subjective age (on grandparenthood, see e.g. Bordone and Arpino, Reference Bordone and Arpino2016) and indicated that women hold more youthful age identities than men (Barrett, Reference Barrett2005). A study on unequal perceived quality of life among older people in Italy suggested that gender, more than any other variable, differentiates individuals’ approaches to old age (Aureli and Baldazzi, Reference Aureli and Baldazzi2002).

Socio-economic status may also play a significant role in affecting individuals’ perceptions of ageing. When education has been used as a proxy for it, large inequalities have been found in terms of objective measures of ageing, such as health (Eikemo et al., Reference Eikemo, Huisman, Bambra and Kunst2008; Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Kye, Teruel and Rubalcava2017). It is therefore our goal to explore whether these discrepancies might also be found in terms of subjective perceptions of ageing. The literature so far shows mixed evidence also in this respect. Whereas Bergland et al. (Reference Bergland, Nicolaisen and Thorsen2014) found that lower-educated individuals tend to feel more youthful than their higher-educated counterparts, other studies showed that respondents who felt older had significantly fewer years of education (Barrett, Reference Barrett2003; Rubin and Berntsen, Reference Rubin and Berntsen2006). Moreover, Kaufman and Elder (Reference Kaufman and Elder2003) reported no significant effect of education on subjective age. Yet, Aureli and Baldazzi (Reference Aureli and Baldazzi2002) found that education is also an important factor in the approach to old age in Italy.

In light of this, we explore differences in whether people feel old and in the events associated with such a feeling, by gender and educational attainment. Identifying gaps in perceptions of old age and understanding the reasons behind them is crucial for the implementation of policies tailored at guaranteeing wellbeing in later life for all sub-groups of the population.

Ageing in Italy

Italy is nowadays an ageing country, like most of the world's areas. However, its ageing process differs from that of, for example, other European countries. While in Sweden and in the UK the proportion of people aged 65+ was already above 10 per cent in 1951, at that time only 8 per cent of the Italian population was ‘old’. Yet now, 60 years later, Italy is among the ‘oldest’ areas in the world (Tomassini and Lamura, Reference Tomassini, Lamura and Uhlenberg2009). The challenges of such a rapid population ageing are therefore unique in this country and the investigation of self-perceptions of ageing gains a special meaning there. Improved health status, increased economic spending and greater expectations on the part of the older people have given rise to the need to redefine ageing in Italy (Aureli and Baldazzi, Reference Aureli and Baldazzi2002).

Most of the studies on age identity so far have investigated the United States of America context (e.g. Logan et al., Reference Logan, Ward and Spitze1992; Barrett, Reference Barrett2003; Bordone and Arpino, Reference Bordone and Arpino2016). However, as this is likely to have a high impact at the cultural level as well as on policy making in Italy, detailed studies accounting for socio-demographic structures and focusing on this country are needed.

In terms of the variables of interest in this study, we note that Italian women belonging to the cohorts considered are less educated and more likely to have been out of the labour market during their life than men. Thus, some changes in roles usually associated with age, such as retirement, may be less or not at all traumatic among women. Moreover, Aureli and Baldazzi (Reference Aureli and Baldazzi2002) have shown that a time-lag exists between men and women in terms of passive acceptance of old age: Italian women seem to delay it until age 75; while for men it occurs earlier. However, men tend to maintain interests and commitments outside the family throughout old age, which women reduce or give up earlier. The same study has also pointed out that both higher- and lower-educated people in Italy react against a passive acceptance of old age. Yet, while higher-educated people opt for new interests and commitments, their lower-educated counterparts tend to engage more within the family. For example, Italian grandmothers report one of the highest European shares of grandchild care on a regular basis, especially among those with lower educational attainment (Bordone et al., Reference Bordone, Arpino and Aassve2017). This is reflected in the top score of Italy in the Active Ageing Index's dimension of social participation: Italian older adults remain active in society mainly by engaging in family activities, especially as grandchild care providers (Zaidi et al., Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Zolyomi, Schmidt, Rodrigues and Marin2017). With Italy being a familialistic context where family roles are particularly valued and are found to be a main component of happiness in later life (Sotgiu et al., Reference Sotgiu, Galati, Manzano and Rognoni2011), one might wonder whether old age there would be considered more as an achievement rather than in pejorative terms. A qualitative study looking at how older people are described in the press in Poland showed that they are portrayed as respected and appreciated for their involvement with grandchildren. However, only in the family sphere did the word ‘grandma’ evoke positive emotions. Older people were often discussed as burdens and, from the market perspective, they were mainly seen as pensioners, i.e. in a post-productive age (Wilińska and Cedersund, Reference Wilińska and Cedersund2010). We argue that these results could be cautiously extended to the case of Italy because the two countries are similar in terms of provision of intensive grandchild care (Bordone et al., Reference Bordone, Arpino and Aassve2017) and also share numerous similarities that might affect the value of the family and intergenerational relationships, such as attachment to Catholic values (Matysiak and Vignoli, Reference Matysiak and Vignoli2013) and (scarce) availability of public child care for children aged 0–2. They also resemble each other in the family policy- and labour market-related contexts (Matysiak and Vignoli, Reference Matysiak and Vignoli2010).

Evidence from a number of countries has instead shown that, although differently across types of programmes, older people are still heavily under-represented in television programmes (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Rakoczy and Staudinger2004). Moreover, most of the older characters are portrayed as affluent, powerful and (physically, mentally and socially, but not sexually) active (Bell, Reference Bell1992). Researchers in this field who have focused on Italy argue that such a mystification of old age shows that old age in Italian society today is mainly linked to a negative meaning (Termini et al., Reference Termini, Burrascano and Pagano2011).

Data and methods

Data

We use secondary data collected in 2013 through a survey carried out within the project entitled ‘“Non mi ritiro”: l'allungamento della vita, una sfida per le generazioni, un'opportunità per la società’ (‘“I Don't Want to Be Inactive”: A Longer Life, a Generational Challenge, an Opportunity for Society’). Both Italian and international researchers were involved in this project funded by the Catholic University of Milan. Given that the main publication describing this survey is in Italian (Lanzetti, Reference Lanzetti, Scabini and Rossi2016), we report here the most important details about the sampling method and the questionnaire.

The target population are persons aged 65–74 who were residing in Italy on 1 January 2013. This survey uses the same sampling scheme as the fourth wave of the European Value Survey, i.e. a two-stage stratified random sampling design. In the first stage, within strata defined by the Italian regions and municipalities’ population size, 90 municipalities were selected with a probability proportional to their population. Within the selected municipalities, individuals were then randomly drawn from electoral lists. It should be noted that Italian electoral lists, available at municipal offices for research purposes and in other cases described by law, other than electoral information also include demographic data (e.g. gender, place and date of birth) of the individuals.

The survey designers established 900 as the sample size necessary to be reached, following a rigorous research design that minimises non-response and sampling errors. The maximum margin of error for a proportion was calculated to be 3 percentage points. As in the European Value Survey, there was no substitution of the non-respondents in order to incentivise the interviewers, who were paid on the basis of the completed interviews they carried out (each being assigned no more than 20 interviewees). They contacted 1,600 units. This implies a response rate of 56.3 per cent which is in line with usual response rates of surveys on older people (e.g. the Italian Wave 1 of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe had a household response rate of 54.5 per cent, see http://www.share-project.org/data-documentation/sample.html).

Concerning the main structural variables (gender, age and marital status), the sample is statistically representative without introducing any adjustment. However, as in all social surveys, people with higher education are more likely to agree to participate. This may create some representativeness issues as it may result in an over-estimation of higher educational levels. In order to reduce such distortion, weights have been used for education only, in a way that would not affect the other structural variables (for more details about the sampling method and the questionnaire, see Lanzetti, Reference Lanzetti, Scabini and Rossi2016). Face-to-face interviews were conducted between November 2013 and January 2014 by professional interviewers who received specific training by the C.R.S. (Centro Ricerche Sociali [Social Research Centre] S.a.s., Milan), to whom the field work was commissioned. The total sample size includes 900 respondents (437 men and 463 women). The questionnaire contains a rich set of information on characteristics, perceptions and conditions potentially related to active life, such as health, socio-economic status, employment, social and family networks, use of new technologies and attitudes.

The working sample in the following analyses is of 408 men and 420 women. We have excluded observations with missing values in any of the variables described below (two on whether the respondent thinks they are considered old by society; four on importance of religion; 64 on visits and calls with children and/or grandchildren; two on physical limitations). In the descriptive analysis of when a person has felt old, respondents who declared to have never felt old are also excluded.

Dependent variables

The questionnaire contains four questions relevant to our work, referring to whether the respondent feels old, whether they think that society considers them to be old, the occasions on which they felt old and the situations that make a person feel old. Drawing on the answers to these questions, the dependent variables considered in this study are the following:

• Self-perception as old: in answering the question ‘Do you feel old?’, respondents can mark one of the four answers offered (not at all, a bit, quite a bit, very much). We consider the four-item scale in descriptive analyses. To avoid sample size issues, the original answers are collapsed into two categories, creating a dummy variable for the multivariate analyses with value 0 if ‘not at all or a bit’ and value 1 if ‘quite a bit or very much’.

• Society perception as old: we investigate descriptively the four-item scale (not at all, a bit, quite a bit, very much) in answer to the question ‘Do you think that society considers you to be old?’ As for the first outcome, in the multivariate analyses the original answers are collapsed into two categories, creating a dummy variable with value 0 if ‘not at all or a bit’ and value 1 if ‘quite a bit or very much’.

• Events when one has felt old: out of the original eight options offered to answer the question ‘When did you feel old?’, we created seven dummy variables with value 1 if the respondent mentioned ‘never’, ‘at retirement’ (combining the options ‘at retirement’ and ‘when stopped working’), ‘when turning 65’, ‘with declining physical independence or with health worsening’, ‘when became a grandparent’, ‘with widowhood’, ‘at parents’ death’, respectively; value 0 otherwise. Only one answer could be marked by the respondent. These answers are analysed descriptively for people that did feel old (i.e. did not answer ‘never’).

• Causes making a person feel old (in general): the questionnaire offers nine options to answer the question ‘What most makes a person feel old?’: ‘loneliness’, ‘not knowing how to kill time (i.e. boredom)’, ‘lack of projects for the future’, ‘(decrease in) physical health’, ‘economic difficulties’, ‘exclusion from technology’, ‘death of loved ones’, ‘decreasing social relationships’, ‘retirement’. Respondents could mark up to three answers. For the multivariate analyses, we created a dummy variable for each possible answer, with value 1 if the answer was selected and 0 otherwise. We acknowledge that some sub-categories, e.g. boredom and lack of projects for the future, might seem to reflect similar concepts. If this is the case, we might observe very similar results in the analyses of these variables. However, as these were offered as different options to the respondents, we decided to keep them separately. Moreover, the first (boredom) hints to a present situation while the latter (lack of projects) rather points to the future.

It is important to note that, differently from the third question, this last question is not conditional on whether the respondent has ever felt old. That is, even respondents who reported having never felt old will answer about what they think, in general, makes a person feel old. Therefore, these latter answers may give us a more general view about events that are associated with the idea of being old.

Independent variables

The main explanatory variables are gender and education. Concerning gender, 48.6 per cent of respondents are men and 51.4 per cent are women. In terms of education, we distinguish three levels of attainment: lower (up to primary school), middle (lower secondary education, i.e. scuole medie) and higher education (at least high school). In our sample, 35.8 per cent of respondents have up to primary education, 30.9 per cent have lower secondary and 33.3 per cent have higher education.

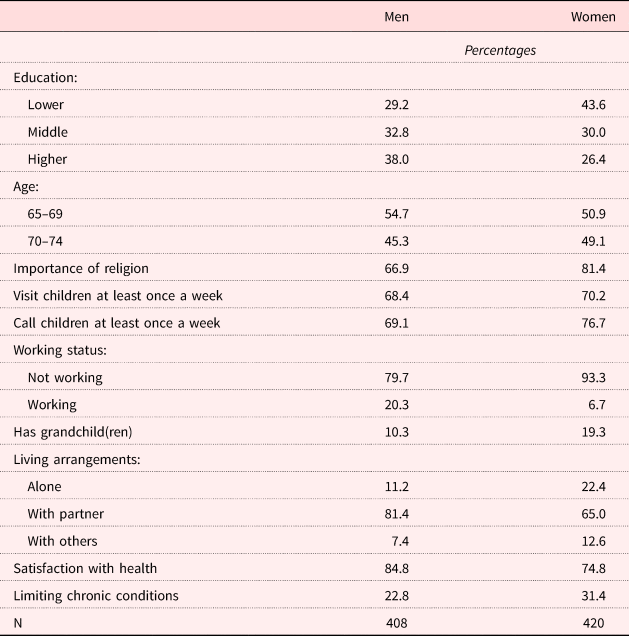

Additionally, in the multivariate analyses the following independent variables were included based on past evidence regarding the determinants of age identity. Descriptive statistics on the independent variables are presented, by gender, in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the independent variables, by gender

In terms of socio-demographic characteristics of the respondent, we control for age by including a dummy variable (0 = 65–69; 1 = 70–74) because, as discussed by Choi et al. (Reference Choi, DiNitto and Kim2014), perceptions of ageing among older adults tend to differ by age group.

Being single may be a predictor of feeling young(er), especially for the younger adults (Bergland et al., Reference Bergland, Nicolaisen and Thorsen2014), although not all studies found a significant relationship between marital status and subjective age (e.g. Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Goldsmith and Flynn1995). The living arrangement variable indicates whether the respondent lives alone (reference), with a partner or with other people only (i.e. excluding the partner).

Working status indicates whether the respondent is working or not working (reference) at the time of the interview. The literature on retirement and perceptions of ageing shows mixed findings. Although the loss of a critical and economic role may characterise the image of old age (for a review, see Kaufman and Elder, Reference Kaufman and Elder2003), Logan et al. (Reference Logan, Ward and Spitze1992) found no significant effect of retirement on age identity once age was controlled.

Recently, an association has been shown between providing grandchild care and feeling younger among both grandfathers and grandmothers above 70 years old (Bordone and Arpino, Reference Bordone and Arpino2016). Therefore, we control for whether the respondent has grandchildren (= 1 if they have at least one grandchild; = 0 otherwise). We also control for the frequency of face-to-face contact and calls with children and grandchildren. Face-to-face contact accounts for both visits to and from the children. Additional analyses considered these as two separate variables, but results did not differ (available on request). For both visits and calls variables, the original categories have been collapsed into ‘at least once a week’ versus ‘less often’.

We additionally account for religious values by including a variable on how important religion is for the respondent. The original four-item scale has been collapsed into a dummy variable with value 1 if ‘quite important’ or ‘a lot’ and 0 if ‘not much important’ or ‘not at all’.

Concerning health, Knoll et al. (Reference Knoll, Rieckmann, Scholz and Schwarzer2004) showed that functional limitations may be more important to the construction of subjective age than their underlying health-related causes. We therefore control for whether the respondent has chronic conditions (since at least six months or expected to last at least six months) causing some or severe limitations in activities. As Macia et al. (Reference Macia, Duboz, Montepare and Gueye2012) found that self-rated health predicted felt age and feeling old, we also control for the subjective perception of health, considering a dummy variable which equals 1 if the respondent is ‘quite’ or ‘a lot’ satisfied with their own health and 0 otherwise. This allows us also to account for the multi-dimensionality of the concept of health. Robustness checks considering the sub-sample without disabilities showed similar results to those reported here.

Preliminary analyses have also controlled for the region of residence by including three dummy variables (North-East, Centre, and South or Islands, North-West being the reference). However, little variation was shown, with the exception of southern Italians being significantly less likely than their counterparts from the North-West to report feeling old and being considered old. Given the relatively small sample, we have decided not to include such a control in order to minimise the number of variables included in the models.

Methods

Our analyses are carried out in two steps. First, we show descriptive associations considering feeling old, being considered old, the occasions in which the respondent felt old and the events that they associate with being old, by gender and education.

Second, we carry out multivariate analyses using a set of logistic regression models, where the dependent variables are feeling old, being considered old and each of the nine items indicated as general causes to feel old.

Our goal of examining differences by gender and education implies a practical issue in terms of smaller sample sizes. This has an impact on standard errors and p-values that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. However, as now recognised by many scholars (see e.g. Nuzzo, Reference Nuzzo2014; Bernardi et al., Reference Bernardi, Chakhaia and Leopold2017), statistical significance and p-values are neither as reliable nor as objective as usually assumed and more attention should be paid to the actual size of effects, differences, etc., rather than to p-values only. Therefore, in the interpretation of results we shall put more emphasis on their substantive relevance than on their statistical significance. Nonetheless, we report the p-values in all the tables for the sake of transparency and completeness.

Results

Do people feel old?

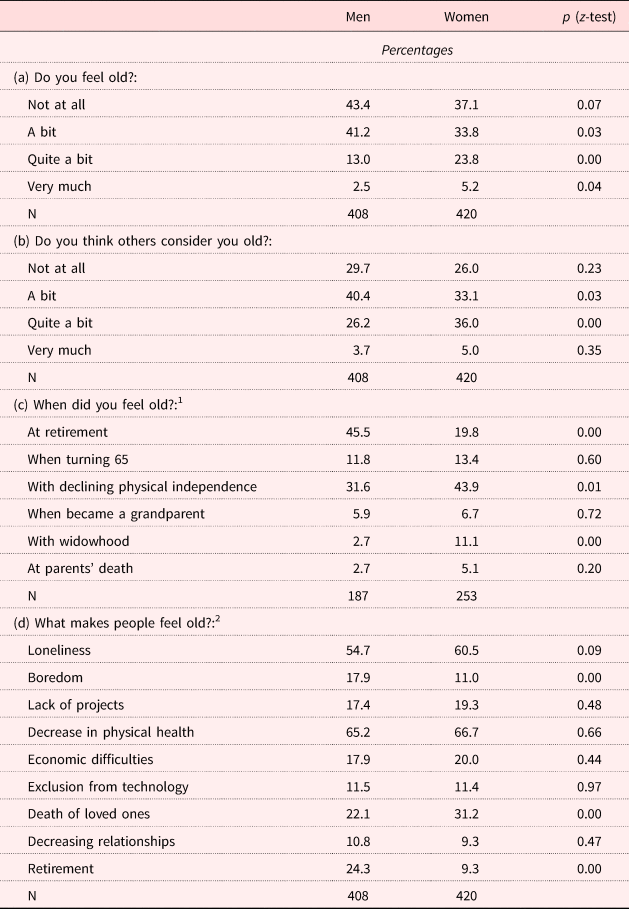

Table 2(a) shows that among men, 43 per cent of respondents do not feel old at all, 41 per cent report feeling ‘a bit’ old, 13 per cent feel ‘quite a bit’ old and about 3 per cent feel old ‘very much’. The percentages among women are 37, 34, 24 and about 5, respectively; p-values corresponding to z-tests of the differences between genders are reported in the last column. As noticed above, we however discuss the results focusing on substantive significance.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables, by gender

Notes: 1. Only one option could be chosen. Sample of respondents who did not answer ‘never’. 2. Up to three options could be chosen.

Interestingly, when looking at the answers to the question ‘Do you think that society considers you to be old?’ (Table 2(b)), the gender differences for the two extreme categories decrease, while they remain substantial for the two intermediate categories (‘a bit’ and ‘quite a bit’). Indeed, about 30 per cent of respondents of both genders do not think they are considered old at all and only about 4–5 per cent answer ‘very much’. Yet, women report a higher tendency towards being perceived old by society (36% answer ‘quite a bit’) than men (26%). It should be noted that women in the sample are, on average, as old as men (69.4 versus 69.3).

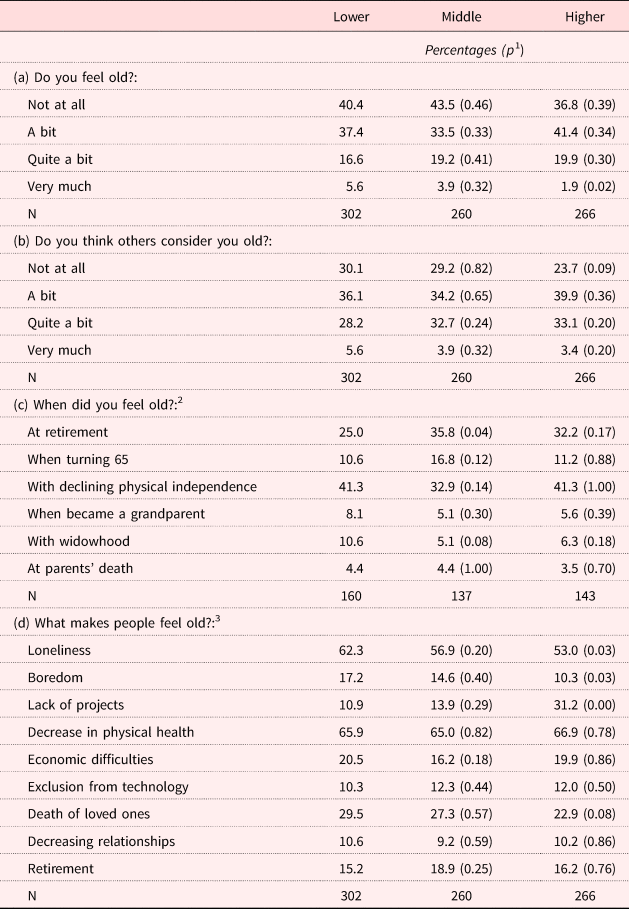

We implemented the same analyses by educational attainment (Table 3(a) and (b)) and found only a few remarkable differences in terms of whether the respondents feel old. In particular, feeling old ‘very much’ is more common among lower-educated than among higher-educated respondents (5.6% versus 1.9%; p = 0.02). Concerning being considered old by society, descriptive statistics hint at a tendency of the lower-educated to report more extreme answers than the higher-educated respondents (with the percentage of ‘not at all’ much higher among lower-educated respondents).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables, by education

Notes: 1. p-values of z-tests with reference to lower education. 2. Only one option could be chosen. Sample of respondents who did not answer ‘never’. 3. Up to three options could be chosen.

When do people feel old?

We then considered the answers to the question ‘When did you feel old?’ We first compared the answers by gender and then by educational attainment. In the male sample, 53.8 per cent said they have never felt old. The corresponding percentage among women is considerably lower (39.2%; data not shown in the tables). Concerning the slightly different prevalence of men and women who currently do not feel old at all, as reported in the first row of Table 2(a), we should note that about 80 per cent of the respondents answer the two questions consistently (i.e. people who report feeling old indicate what made them feel old and people who report having never felt old also mention not feeling old). Yet, 7.3 per cent of the male sample and 6.9 per cent of the female sample report having felt old at some point in the past but their evaluation of their own ageing has changed, indicating that feeling old is not necessarily interpreted by individuals as an absorbing status. Moreover, about 12 per cent of respondents report having never felt old, but indicate that they currently feel ‘a bit’ old. These respondents are mainly men, slightly younger than the rest of the sample, still working and living with their partner in a higher proportion than in the other sub-groups. They are therefore less likely to have experienced feeling old as linked to the events that most commonly represent old age. Indeed, they do not report having ever felt old and for the more general question ‘Do you feel old?’ they answer ‘a bit’ (not ‘quite a bit’ and not ‘very much’). We interpret this as a general feeling linked to a projection of the approaching changes (retiring, losing a partner, etc.). However, it should also be noted that the two questions are of a different type (e.g. one relying on a scale and the other on binary categories) and use a different time-frame (one uses a verb in the past tense and the other refers to the present), preventing us from further speculation about their comparison.

Table 2(c) summarises, by gender, the events that people link to having felt old, among respondents who did not answer ‘never’. We start noting that men report retirement as an event at which they felt old (45.5%) much more often than women (19.8%; p < 0.01). Retirement is indeed the dominant event linked to feeling old among men. However, such a gender-specific answer may derive from the fact that fewer women in the cohort considered have worked compared to men. Since a large number of the women in the sample have likely not experienced retirement, they will not report it as a reason for feeling old. Unfortunately, the survey does not provide further information about working careers in order to better understand this result. The status mainly linked to having felt old among women is decline in physical independence (43.9% versus 31.6% observed for men; p = 0.01). Women also report having felt old because of widowhood (11.1%) more often than men (2.7%; p < 0.01).

Turning 65 and becoming a grandparent are reported as events at which respondents have felt old in similar proportions among men and women (11.8% of men and 13.4% of women mention turning 65; 5.9% of men and 6.7% of women mention grandparenthood). It is particularly interesting to note that the common criterion to define ageing and old age (i.e. crossing the threshold of age 65) is only marginally reported by older people as a relevant marker of old age. Life events seem to matter more than chronological age to define the entrance into old age.

The proportion of respondents who declared that they never felt old does not vary appreciably with education (the percentages being 46.5, 47.1 and 45.6 for lower-, middle- and higher-educated respondents, respectively; data not shown in the tables). Table 3(c) describes the distribution of the events associated with having felt old, among respondents who did not answer ‘never’, by educational attainment. All three sub-groups report retirement and decline in physical independence as the two main occasions at which they felt old. The only noticeable differences are for the lower-educated respondents reporting retirement and widowhood, respectively, less and more often than their counterparts with higher levels of education.

What makes a person feel old (in general)?

Table 2(d) shows the distribution of the answers for men and women to the question ‘What most makes a person feel old?’ This is a more general question than the one analysed above as it does not directly depend on the respondents' personal experiences. Therefore, it also allows us to better capture the factors that people associate with perceptions of ageing. In this case, the percentages for the different categories do not sum up to 100 because respondents could mention up to three motivations linked to feeling old. Moreover, all respondents are included in these analyses, independently of whether they have ever felt old. The most frequently mentioned reason for feeling old is a decrease in physical health, reported with very similar percentages among both men and women (about 65%). The second one is loneliness, especially for women: the percentage of women mentioning that loneliness makes people feel old (60.5%) is slightly higher than that of men (54.7%; p = 0.09).

Among the other causes reported, retirement and boredom are more likely to be associated with feeling old for men than for women. These latter, however, report the death of loved ones considerably more often (31%) than their male counterparts (22%; p < 0.01).

Comparing respondents by educational attainment (Table 3(d)), we find that loneliness and decrease in physical health are reported as the main reasons for feeling old across all educational categories. However, there is a negative gradient in reporting loneliness as a main reason for feeling old over education. More specifically, among lower-educated respondents, 62 per cent mention loneliness versus 53 per cent of the higher-educated respondents (p = 0.03).

The proportion of those who mention ‘boredom’ as a reason for feeling old is also higher among lower-educated respondents as compared to those with higher education (17% versus 10%; p = 0.05). Similarly, death of loved ones is reported to be associated with feeling old more frequently among respondents with lower educational attainment than among higher-educated respondents (30% versus 23%; p = 0.08). However, the lack of projects for the future is considerably more likely to be associated with feeling old among the higher-educated as compared to the lower-educated respondents (31% versus 11%; p < 0.01).

Regression results

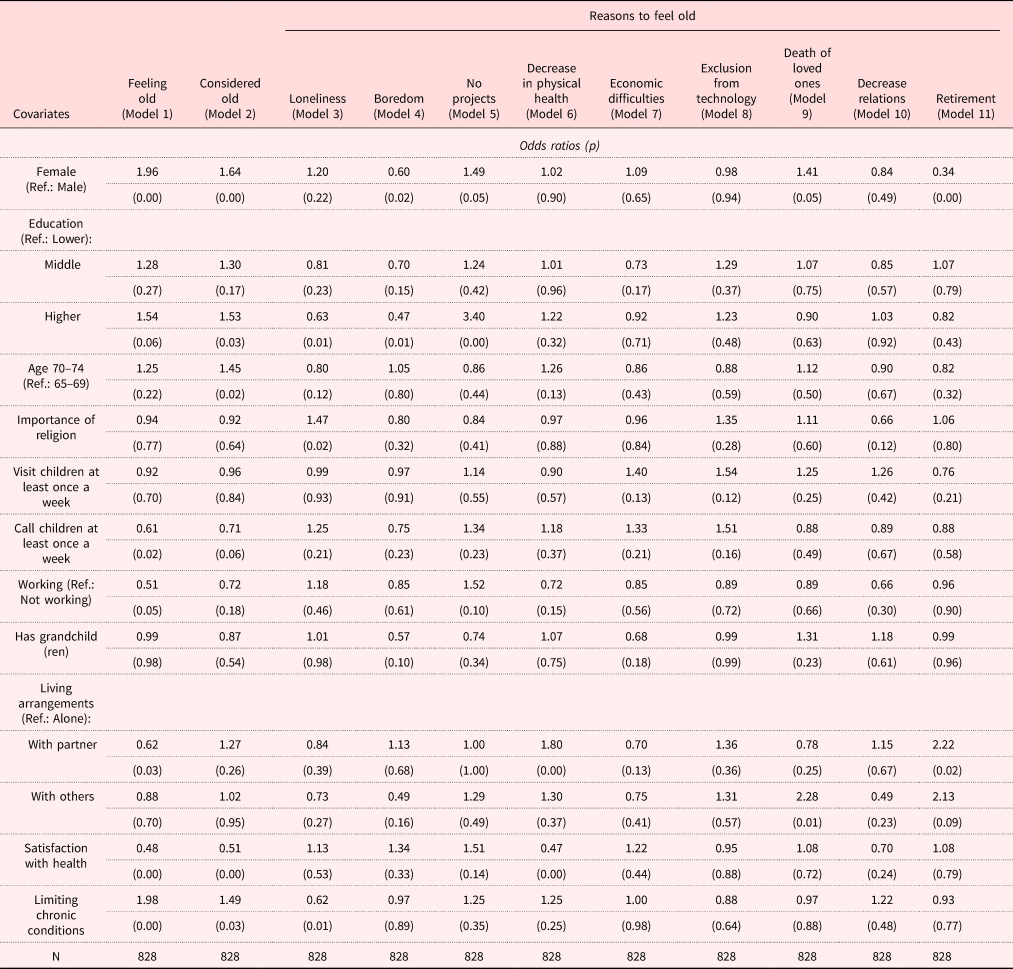

In a second step, we carry out multivariate analyses (the results are reported in Table 4). First, we estimate two logistic models where we consider whether the respondents feel old (= 1 if very much or a bit; = 0 otherwise; Model 1) and think they are considered old (= 1 if very much or a bit; = 0 otherwise; Model 2), respectively. Second, each of the answers to the question ‘What most makes a person feel old?’ is used in turn as a dependent variable in a set of logistic models (Models 3–11). Our explanatory variables of interest are gender and education.

Table 4. Odds ratios estimates (standard errors in parentheses) from logistic regressions

Note: Ref.: reference category.

Results show that, net of the other covariates included in our models, women are more likely than men to feel old (Model 1) and to think that society considers them old (Model 2). Moreover, women are less likely than men to link feeling old with boredom (Model 4) and retirement (Model 11), but they more often associate it with lack of projects for the future (Model 5) and death of loved ones (Model 9). These results generally confirm the descriptive findings.

In contrast to the descriptive results, where little variation was found by educational attainment, the multivariate analysis shows that people with higher education are more likely to feel old (Model 1) and to think they are considered old (Model 2) than their counterparts with up to primary education. The multivariate models confirm that people with higher education are less likely to associate feeling old with loneliness and boredom (Models 3 and 4) and more likely to link it with lack of projects (Model 5) than their lower-educated counterparts.

While the associations between the other independent and the dependent variables considered are in general in line with what one could expect, it is interesting to note the results for frequent calls with (grand)children. People who have at least one phone call per week with their children and/or grandchildren are less likely to feel old and to think they are considered old as compared to their counterparts with less-frequent intergenerational contacts. Moreover, grandparents are less likely to report boredom as a cause for feeling old than their grandchildless counterparts.

As a robustness check, we carried out all the models in Table 4 (except the first one) only on those respondents who reported feeling at most ‘a bit’ old (i.e. we only retained respondents that felt ‘a bit’ or ‘not at all’ old, N = 643). This reduced the possibility that their own experiences of feeling old affected the answers to the more general question about ageing. The results were very similar to those shown in the paper (available on request) and we therefore preferred to keep a larger sample in the analyses.

Discussion and conclusions

Drawing on the recently revived literature on the importance of the subjective dimension of ageing and making use of a unique data-set, this study focused on differences by gender and education with respect to whether people feel old and think they are considered old by society, and on the reasons associated with perceptions of ageing among Italians aged 65–74.

Our findings point to a high degree of heterogeneity in the prevalence of feeling old and its (perceived) determinants even within a relatively homogeneous age group living in the same country and observed at the same time. More specifically, our results show considerable variability both by gender and education. Understanding these gaps in perceptions of old age is crucial for the implementation of policies tailored at guaranteeing a high quality of ageing for all sub-groups of the population. Indeed, previous evidence has shown that older individuals with more positive self-perceptions of ageing, measured up to 23 years earlier, lived 7.5 years longer than those with less-positive self-perceptions of ageing (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002).

As for differences by gender, we found that women are more likely than men to feel old and to think that society considers them to be old. Previous studies on subjective age focusing on the question ‘How old do you feel?’ found that on average women feel younger than men and experience greater discrepancies between their actual and subjective age than do their male counterparts (e.g. Montepare and Lachman, Reference Montepare and Lachman1989). In this respect, our analyses seem to differ from previous evidence. Yet, Aureli and Baldazzi (Reference Aureli and Baldazzi2002) also provided evidence of a gendered time-lag in terms of passive acceptance of old age in Italy, with women accepting old age, on average, later than men. We should note that these concepts measure the complex age identity construct and they might also depend on the socio-cultural gendered meaning of ageing. In this respect, our study goes beyond the question ‘Do you feel old?’ and digs into the reasons to have felt old, providing evidence on the individual interpretation of ‘old’.

Among men who did feel old, the main event reported to be associated with having felt old was retirement; for women it was the loss of physical independence, but they also frequently listed widowhood and death of parents. However, when asked to report the reasons why in general people feel old, both men and women mentioned loneliness and worsening health. We should thus reflect on the image of old age as promoted for example by the media, where (as mentioned in the Background section) older people are mostly portrayed as relatively physically, mentally and socially active (Bell, Reference Bell1992). This somehow mystifies old age (Termini et al., Reference Termini, Burrascano and Pagano2011) in the same way as a superstitious runner hypothetically asked at the 42nd kilometre, while having a significant advantage, would not admit to believing they would win a marathon in order to keep far away the negative events that might happen on the way to the finish line (i.e. the negative aspects of ageing, as linked to its label).

Multivariate analyses used to explore the individual characteristics associated with the different reasons to feel old show that women tend to associate feeling old with lack of projects for the future more often than men, while men are more likely to link it with boredom and retirement. Such heterogeneity across gender might derive from the gendered roles in society and from different personal experiences by gender. Indeed, fewer Italian women in the cohort considered have entered and stayed in the labour market throughout their working age as compared to men. This might explain why women in the sample tend to link old age to retirement less. As housekeepers, these women have probably shouldered most of the housework and family care. It would therefore be interesting to investigate further whether in the female sample there are differences in the perception of feeling old, for example, between those who do grandparental child care and those who do not. In an analysis of the US American context, Bordone and Arpino (Reference Bordone and Arpino2016) reported that older women engaged in grandchild care tend to feel younger than their grandmother counterparts not engaged in grandchild care.

Feelings about old age were also found to be substantively heterogeneous with respect to education. Respondents with higher education are, for example, less likely to associate feeling old with loneliness and boredom as compared to their counterparts with lower educational attainments. This might reflect the higher engagement in social activities among higher-educated people (Arpino and Bordone, Reference Arpino and Bordone2017) that, in turn, is likely to also help them maintain larger social networks outside the family. This might be particularly true for the young older people considered in this study (i.e. 65–74 years old).

However, our findings across gender and educational groups also reflect the complexity of the ageing process and of self-perceptions of ageing. By contributing to the understanding of whether and when sub-groups of the population feel old, we shed light on the mixed evidence provided by previous studies that focused on subjective age (e.g. by education: Barrett, Reference Barrett2003; Kaufman and Elder, Reference Kaufman and Elder2003; Rubin and Berntsen, Reference Rubin and Berntsen2006; Bergland et al., Reference Bergland, Nicolaisen and Thorsen2014). Yet, future studies, also through qualitative investigations, will need to address these issues more in depth to improve our knowledge of the changing meaning of ‘old age’.

In fact, the evidence we presented shows that, independent of gender and education, most people aged 65–74 do not feel old while they would be categorised as such according to traditional measures of ageing based on chronological age. Declaring not to feel old carries valuable information. On the one hand, it may for example indicate that people feel healthier than they would expect to be at their chronological age (Barrett, Reference Barrett2003; Westerhof and Barrett, Reference Westerhof and Barrett2005). This may have important direct and independent consequences on subsequent engagement in social activities, health-related behaviours and future wellbeing outcomes (Sargent-Cox et al., Reference Sargent-Cox, Anstey and Luszcz2012; Low et al., Reference Low, Molzahn and Schopflocher2013; Yannick et al., Reference Yannick, Chalabaev, Kotter-Grühn and Jaconelli2013; Westerhof et al., Reference Westerhof, Miche, Brothers, Barrett, Diehl, Montepare, Wahl and Wurm2014).

On the other hand, reporting not feeling old might reflect a form of self-preservation to maintain an identity consistent with that of one's younger self (Montepare and Lachman, Reference Montepare and Lachman1989). While the ageing process per se does not carry a negative connotation if referred to as a lifecourse process, a negative meaning emerges when there is a perception of entering the final stage of the lifespan. This is indeed the widespread correspondence assumed by the definition of old age, even in sources that are expected to be neutral like dictionaries (see e.g. the definition given by https://www.britannica.com/science/old-age and http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/old-age). Such a ‘final stage’ of life is characterised not only by changes as in previous stages, but also by progressive irreversible losses that reinforce the negative meaning attached to old age. Negative societal perception of old age can be found in most cultures across the world, mainly driven by age stereotypes (Kotter-Grühn, Reference Kotter-Grühn2015). Even in the context of Italy, a traditionally familialistic country where older people are recognised and valued in their family roles, e.g. as grandparents, culturally shared beliefs about older people view them as sick, dependent, weak or lonely (Hummert, Reference Hummert, Hess and Blanchard-Fields1999), all features that are characterised by low desirability.

Consistently, the data we analysed hint to a higher degree of feeling old among those people who lost physical independence, those who lost a partner, as well as in association with loss of incentives, projects and social relations.

‘Feeling old’ might be seen in antithesis with active ageing when asking ‘Do you feel old?’ or ‘How old do you feel?’ The cultural interpretation of what it is to be old in modern societies is in fact a result also of the extent to which the culture is oriented towards youth (Westerhof and Barrett, Reference Westerhof and Barrett2005). Recent studies suggest that the subjective age variable presupposes a normative meaning of chronological age (with 65 being the common threshold), such that people tend to measure themselves against this in order to answer whether they feel old (e.g. Gendron et al., Reference Gendron, Inker and Welleford2018). The results of our study, however, challenge such a perspective, suggesting that ‘young older people’ today do not use chronological age as the key parameter to define their ageing process. Acknowledging that discrepancies exist as to what age in a society may be considered old and what members in that society consider old age to be (Gorman, Reference Gorman, Randel, German and Ewing1999) makes it essential to overcome the traditional definitions of old age based on chronological age and go beyond objective criteria (e.g. remaining years of life) in order to account explicitly for the subjective dimension of ageing.

A central finding of the current study regards the specific criterion commonly used to define old age, i.e. the threshold of turning 65 years old. For both men and women, it is not relevant for the self-perception of ageing as people give more importance to life events than to chronological age when recalling what made them feel old. The fact that the respondents aged 65–74 do not associate turning 65 with feeling old confirms that the threshold of 65 does not correspond any longer with entering ‘old age’. There is no longer a specific and universally accepted chronological age that determines the entrance into ‘old age’ and this may also not necessarily mean simply prolonging the phase of life in which an individual is a (mature) ‘adult’. Rather, a shift is required in reading this change away from traditional thinking in terms of chronological age to emphasise the lifecourse perspective. We were able to describe the prevalence of people in the age range 65–74 who feel old and to identify the main events that made them feel old. Future studies are required to improve our understanding of the subjective dimension of ‘old age’ further.

In light of this, our account of the opinion of the ageing population about their own ageing process is extremely important. Policies that offer opportunities for active participation in society across all strata of the population should aim at reducing the perception of feeling old among older people. This may, also, reduce gender and education differences in the quality of ageing (see e.g. Lifshitz-Vahav et al., Reference Lifshitz-Vahav, Shrira and Bodner2017). Moreover, activities that bring together different generations may not only increase participation of older people but also reduce ageism among the younger generations (e.g. Gaggioli et al., Reference Gaggioli, Morganti, Bonfiglio, Scaratti, Cipresso, Serino and Riva2014; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Joyce, Harwood and Xiang2017). Therefore, in order to promote wellbeing in later life, social activities should be encouraged and a cultural change should be promoted. In this way, the ageing population will be helped to be active, but also to not feel old.

We acknowledge some limitations of our study. In particular, the question on the reasons that make people feel old may still partly reflect personal experiences. Moreover, while previous findings indicated that subjective age may be associated with changes in general health, cognitive functioning (Demakakos et al., Reference Demakakos, Gjonca and Nazroo2007; Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Caudroit and Chalabaev2011) and wellbeing (Keyes and Westerhof, Reference Keyes and Westerhof2012), and may be also affected by daily events (Kotter-Grühn et al., Reference Kotter-Grühn, Neupert and Stephan2015), the list of reasons to feel old included in the survey was limited to a few of these conditions. Furthermore, constructs such as attitudes towards own ageing, awareness of age-related change and subjective nearness/distance to death may mediate subjective perceptions of ageing (Brothers et al., Reference Brothers, Miche, Wahl and Diehl2017; Siebert et al., Reference Siebert, Wahl and Schröder2018). Therefore, it is possible that they also play a role in attributing significance to the specific experiences people associate with their ageing process. Finally, we recognise that as the analysis focuses on an Italian sample of men and women aged 65–74, it does not allow us to generalise the results beyond this sub-population. As the subjective meaning of ageing may also reflect different cultural values and cultural changes linked, for example, to the portrayal of older people in the media (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Rakoczy and Staudinger2004; Termini et al., Reference Termini, Burrascano and Pagano2011), future studies should investigate this topic by comparing perceptions of the ageing of men and women across different countries/cultures and different cohorts. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data available, we could only establish associations between various events and the perception of being old. The use of longitudinal data in future studies may allow better exploration of the causal importance of life events in defining the subjective dimension of ageing.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our analyses significantly add to previous studies on the subjective meaning of ageing. As advocated, for example, by Choi et al. (Reference Choi, DiNitto and Kim2014: 470), ‘older adults should be asked to elaborate on the reasons they felt younger, the same, or older than their chronological age’. Although some previous studies analysed factors associated with perceptions about feeling old, they could not exploit direct information on what respondents think to be the reasons for feeling old in general or in their personal experience. The unique data we used in this paper allowed us to deepen the understanding of lifecourse events and individual conditions that may define the concept of ‘old age’. More data collection efforts should continue along the lines of the project that generated the data used in this paper. Collecting detailed longitudinal data on perceptions of ageing of different cohorts of people may be a valuable way to contribute to this increasingly important field of literature.

Data

The data used were collected within the project ‘“Non mi ritiro”: l'allungamento della vita, una sfida per le generazioni, un'opportunità per la società’ (‘“I Don't Want to Be Inactive”: A Longer Life, a Generational Challenge, an Opportunity for Society’), funded by the Catholic University of Milan (D3.2 funds).

Acknowledgments

Bruno Arpino acknowledges funding from the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (PCIN-2016-005; PI: B. Arpino) for the project “Care, Retirement & Wellbeing of Older People Across Different Welfare Regimes” (CREW) within the second Joint Programming Initiative “More Years Better Lives”.