Introduction

With population ageing and urbanisation emerging as two dominant trends, ageing in urban geographies and developing ‘age-friendly cities’ have garnered great attention in social policy and research (World Health Organization (WHO), 2007; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2012). The outward growth of cities, particularly in South Asia, has led to low-density sprawls on the peripheries, which tend to be devoid of crucial services such as public transport and opportunities to work and decent life (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Crothers, Grant, Young and Smith2012; Howe, Reference Howe, Carmon and Fainstein2013). This paper explores the ways in which spatial and mobility challenges in a low-income country could further impede ‘ageing in place’ in the urban periphery by impacting the health-seeking behaviour, social participation and economic wellbeing of those aged 50 years and older.

In developing countries, the number of older adults living in cities is expected to multiply 16 times from 56 million in 1998 to over 908 million in 2050 (WHO, 2007). Hence, in the context of extant inadequate support systems which characterise the peripheral urban areas in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), there is a real need to understand the risks of social exclusion for older adults, specifically those who are resource-poor (Scharf and Keating, Reference Scharf and Keating2012). Despite rapid demographic change, there is still relatively little research on older adults in these countries (Rishworth and Elliott, Reference Rishworth, Elliott, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018). This paper, building on a growing body of literature on geographical gerontology, uses the multidimensional social exclusion model of Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017) as an orienting framework to understand how geography and mobilities shape ageing experiences in these rapidly transforming urban peripheries. The study uses transport disadvantage, an important domain in the framework of Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017), as an entry point to explore broader complex issues of social exclusion among older adults in liminal peri-urban spaces. Cognisant of no comparable frameworks from India or the global South, through this analysis, we try to contextualise and nuance the experiences of ageing on the peripheries. This study is a pioneering attempt to research exclusion in later life in a rapidly expanding peri-urban context in the global South, with a focus on the case of the South Indian metropolis of Bengaluru.

Conceptualisation: age-based exclusion in liminal spaces

Peripheral urban areas or peri-urban refers to transitionary and hybrid spaces between urban and rural boundaries (Dupont, Reference Dupont2007; Bartels et al., Reference Bartels, Bruns and Simon2020) which are at the cusp between a village and a city but still wholly neither. As Bartels et al. (Reference Bartels, Bruns and Simon2020) note, the urban–rural continuum is an essential aspect of the scholarship on the peri-urban phenomenon. These urban patches are often sites for constant transformation in land use, socio-demographics and occupational patterns (Caldeira, Reference Caldeira2017). The transition in these spaces across built-in infrastructure, governance jurisdiction and or socio-cultural geography (Simon et al., Reference Simon, McGregor and Nsiah-Gyabaah2004; Bartels et al., Reference Bartels, Bruns and Simon2020) embodies liminal characteristics.

Van Gennep (Reference Van Gennep1960) conceptualised liminal as a transitionary stage and liminality as the ambiguity experienced by an individual or social group during their rites de passage from known social constructions to a new order. Turner (Reference Turner1979) further expanded the concept by recognising the ‘foregrounding of agency’ and the dialectic influence of space and identity in these liminal zones. Since then, liminal spaces have gained interest from urban studies, such as Shields (Reference Shields1991), who distinguishes ‘social periphery and topographical marginalisation’ and their specific roles in creating these liminal zones. The elements of transformation and hybridity create a ‘betwixt’ place, which could dilute place-based identity for older adults. This paper is situated to capture how the receding traditional order of the village and the abstraction of the urban milieu could produce multiple liminal experiences for older inhabitants. Ambiguity permeates the constantly re-shaping lifeworld of migrant as well as native older adults (Grenier, Reference Grenier2012; Thomassen, Reference Thomassen2016; Cutchin, Reference Cutchin, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018). Alongside these subjectivities, infrastructural gaps between the city and village diffuse governance responsibilities, making the space non-mainstream (Simon et al., Reference Simon, McGregor and Nsiah-Gyabaah2004). Uneven peripheralisation and the politics of spatial and social rearrangements increase the risk of social exclusion (Bartels et al., Reference Bartels, Bruns and Simon2020). Further, there is limited understanding of the implications for ageing.

Geographical gerontology has witnessed a growing interest in the socio-spatial factors that impact the wellbeing and exclusion of older adults (Golant, Reference Golant1972; Warnes, Reference Warnes1981; Harper and Laws, Reference Harper and Laws1995; Andrews and Phillips, Reference Andrews and Phillips2004; Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Cutchin, McCracken, Phillips and Wiles2007; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018; Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Gaugler and Kane2020). Place is an integral domain that enables or restricts older adults' access to public services, neighbourhood relations and mobilities (Walsh, Reference Walsh, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018). However, there are knowledge deficits in understanding the exclusion of older adults from different social positions and geographies (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017). Besides, research on the geographies of ageing has had its limitations, such as the predominant focus on the urbanisation experiences of developed countries (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Jones and Turner2019), ‘rural versus urban’ comparisons and spatial inequalities discussed with neat categorisations (Skinner and Rosenberg, Reference Skinner and Rosenberg2005; Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Cutchin, McCracken, Phillips and Wiles2007; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Rosenberg, Lovell, Dunn, Everitt, Hanlon and Rathwell2008). The hybrid nature of peripheries and the impact of such partial transitions on ageing demands a multidimensional approach to old-age disadvantages (Scharf and Keating, Reference Scharf and Keating2012). Multidimensional frameworks, such as those by Burholt et al. (Reference Burholt, Winter, Aartsen, Constantinou, Dahlberg, Feliciano and Waldegrave2020), Levitas et al. (Reference Levitas, Pantazis, Fahmy, Gordon, Lloyd-Reichling and Patsios2007) and Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017), recognise the multi-level and cross-cutting factors influencing exclusion in later life. Building on the concepts of liminality and social exclusion, we orient our evidence using the framework of Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017) to identify the intersecting nature of multiple stressors to explain age-related exclusion. The framework helps situate ageing in the political economy of the peri-urban neighbourhood, material resources, and access to services and social relations.

Exclusion at later age in urban India

Ageing in Indian cities produces unique challenges due to resource constraints in urban infrastructure and environments (Jamuna, Reference Jamuna2000; Pucher et al., Reference Pucher, Korattyswaropam, Mittal and Ittyerah2005; Lamb, Reference Lamb2013; Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Jones and Turner2019). Studies have documented the ‘flourishing’ growth in population and built-up areas on the peripheries of Indian cities (e.g. World Bank, 2013; Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Mahadevia and Williams2020; India Housing Report, 2021). Prominent among them, Bengaluru, once termed a ‘pensioner's paradise’ (Mukherjee, Reference Mukherjee and Wadley2014) for its green spaces and pleasant outdoor experience, is now widely recognised for its unplanned peripheral growth. Pani et al. (Reference Pani, Radhakrishna and Bhat2008) trace the city's history of ‘dominant peripheralisation’ or growth along the boundaries. Shaw and Satish (Reference Shaw and Satish2007) and Goldman's (Reference Goldman2011) conceptualisation of ‘speculative urbanism’ point to the global and local agencies transforming rural economies into urban real estate. Further, Upadhya and Rathod (Reference Upadhya and Rathod2021), studying Bengaluru's peripheries, highlight the ‘rooted histories’ of the caste-based mode of accumulation, not just in land markets but also in political resources. For those with less access to resources, housing in the city boundaries is more economically viable when compared to the core. Kundu et al. (Reference Kundu, Pradhan and Subramanian2002) direct attention to ‘degenerated peripheralisation’ in Indian megacities, which refers to an increase in vulnerable settlers and lack of access to essential services including transport.

Though the peri-urban process has received attention from urban scholars, the experience of ageing in these liminal patches of land is not well sketched out. The present paper draws on a study conducted in Anjanapura, a peri-urban ward in Bengaluru, to understand the experience of ageing in the urban peripheries where markers of age-based social exclusion intersect that of degenerated peripheralisation. The paper employs a qualitative approach to understanding older adults' negotiations with rural–urban confusions, the constant risks of exclusion in later life and the implications for active ageing.

Methods

Study setting

Anjanapura ward, on the southern boundary of Bengaluru, was selected for its suitability for studying both peripheral and socio-economic marginality. It is a peripheral ward containing a large population of older adults from socially (DalitFootnote 1 and Muslims) and economically marginalised groups. Manju, an auto-rickshaw driver and a native of the place, introduced us to the field. On a warm March afternoon, he drove us in his auto-rickshaw past busy Mosque Road towards the old post office swarming with hopeful pensioners. The dusty street was lined with houses on both sides that were squeezed together, unpainted and incomplete. These houses, though asymmetrical, were strictly segregated as AmbedkarFootnote 2 (Dalit) and TipuFootnote 3 (Muslim) lanes denoting social segregation. The main roads were previous alleys widened just enough to fit a Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTCFootnote 4) bus. These streets were packed with auto-rickshaw drivers eagerly awaiting passengers, men sipping tea and reading newspapers, and vigilant pedestrians. Just then, we witnessed a shopkeeper standing on a narrow footpath, providing directions to the bus driver to ensure the bus turned the tight corner without bulldozing the corner tea shop or the bakery. As we waited along with many motorists for the bus to complete its manoeuvre, Manju went on to identify these retail shops with the names of farmers whose farms the commercial buildings had replaced.

Real estate prices in Anjanapura have surged since the erstwhile village was classified as a municipal ward in 2007.Footnote 5 Long-term residents who once frequented the areas as ‘commons’ now find the lakes fenced by the local governing body, the grazing fields acquired by the forest department and the hills cordoned for quarrying (see Figure 1). They use the dusty, congested and loud roads only to visit the post office, temple/mosque or pharmacies. The relatively quiet streets in front of their house were their homes. As Manju and I entered a Dalit Street, we saw eight to ten older adults, men and women, dotting each household, sitting on the jagli. Footnote 6 They soaked in the early morning sunlight, gazed around and spoke to every passerby. On these streets, everyone knew everyone's health issues, loans or domestic conflicts, especially older adults. We sat on these jaglis, opposite the open drain and amidst the bleat of goats and cows, to listen to the lived experiences of older residents of Anjanapura.

Figure 1. The spatial location of Anjanapura ward.

Source: Author's representation.

Study design and data collection

A qualitative approach was used to produce thick descriptions (Hennink, Hutter and Bailey, Reference Hennink, Hutter and Bailey2020) of what it means to age (barriers, coping mechanisms) in the peri-urban region. Traditionally in gerontological research, spatial and ethnographic data have been used independently or as substitutes for each other, thus diluting their potential to be complementary. We have utilised Knigge and Cope's (Reference Knigge and Cope2006) grounded visualisation to ‘systematically integrate’ the visual and ethnographic data (Jones and Evans, Reference Jones and Evans2012; Franke et al., Reference Franke, Winters, McKay, Chaudhury and Sims-Gould2017) to present more detailed explanations of multidimensional factors affecting exclusion in later age.

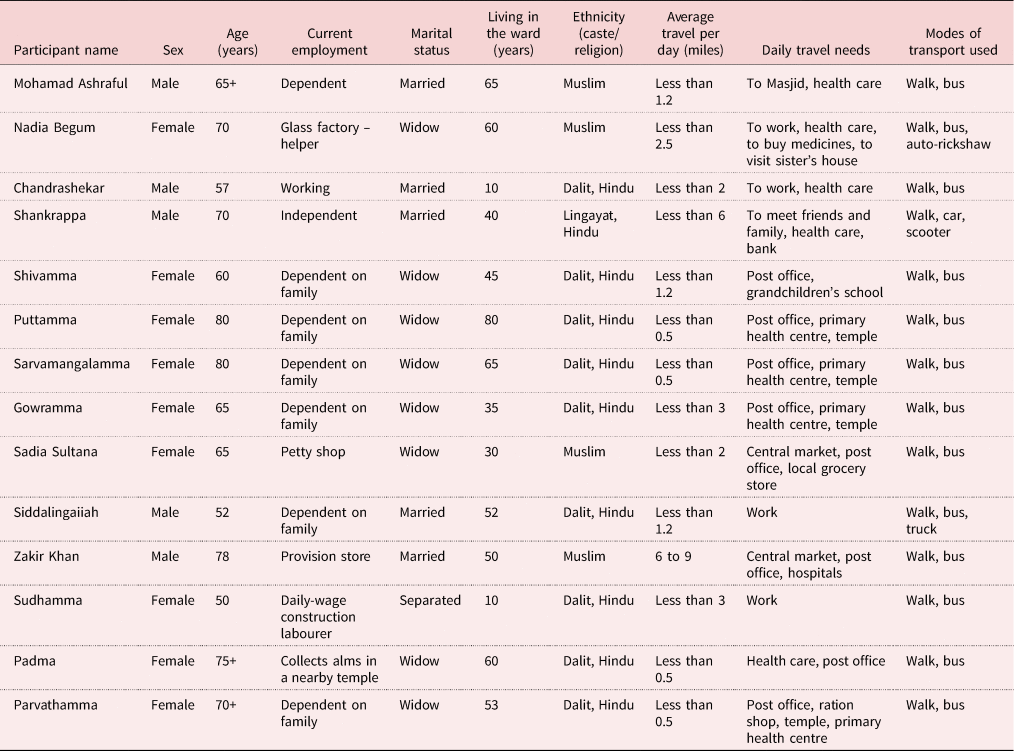

The study used a purposive sampling technique for qualitative in-depth interviews. Overall, 18 interviews were conducted. First, 14 older adults (50–80 years) from socio-economically marginalised groups were interviewed in the neighbourhood (for details, see the Appendix). They were asked about their demographics, migratory history, perception of changes in the area, mobility behaviour (needs, barriers and coping strategies) and experiences of ageing in the neighbourhood. Key informant interviews (four) were conducted with a local Masjid leader, a Dalit leader, a local municipality worker and an auto-rickshaw driver. We used Tremblay's (Reference Tremblay and Burgess1982) framework for selecting key informants, which comprised the following attributes – a significant role in the community, informed knowledge of the research cohort and willingness to share information. The Masjid and Dalit leaders were considered important and influential by their respective communities. They talked about social marginalisation, unity and resilience, and traced the socio-economic trajectories of older settlers. The municipality worker and the auto-rickshaw driver highlighted the contestation for civic amenities, particularly those that were transport-related. These interviews provided a broader understanding of older adults' living conditions and the socio-politics of the peri-urban neighbourhood. On average, the interviews lasted close to an hour. The interviews were conducted in Kannada, the regional language of Karnataka.

Behavioural mapping, a visual survey technique (Ewing and Clemente, Reference Ewing and Clemente2013; Sanoff, Reference Sanoff2016), was used to observe older adults' interactions with their immediate physical environment, as well as their accessibility issues, utilisation of spaces, barriers and enablers in their natural setting. Twenty-two mapping sessions were carried out in the two largest transport hubs of the Anjanapura ward – Tipu Circle and Glass Factory Circle (see Figure 1). Each session consisted of intense observation, sketching and videography of older adults' mobility behaviour.

Institutional ethical clearance was obtained from the funding university and the local partner research institute. With the help of a project information sheet printed in Kannada and English, participants were explained their rights, the purpose of the interview and how the collected data will be used. Written or verbal consent was obtained from them. Participants' identities and data have been kept confidential and anonymous throughout the research process.

Analysis

The 14 older adults and four key informants' in-depth interview recordings in Kannada were translated and transcribed verbatim into English. These texts underwent multiple rounds of coding (both inductive and deductive) using NVivo 12 software. In the first round of open coding, all the data from in-depth interviews and behavioural maps were coded to identify codes and allow for theoretical possibilities (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2021). In the second round of axial coding, researchers began to draw connections between the specified codes by identifying relationships and context, which helped aggregate the code families under themes.

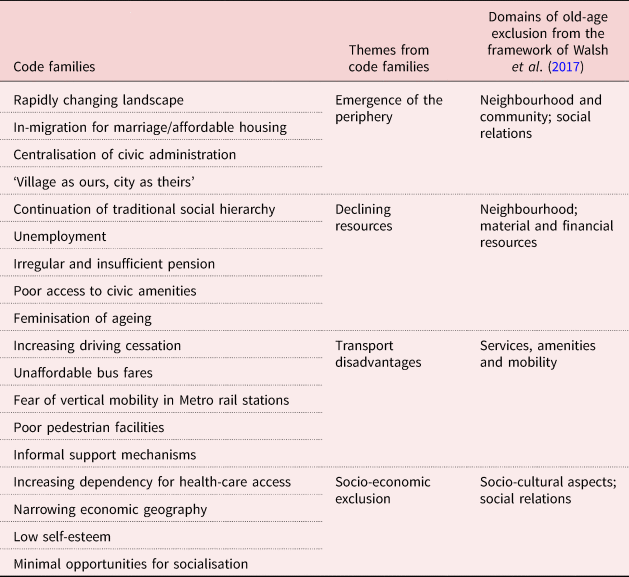

While coding, to enable a healthy interplay between induction and deduction, we allowed the codes and code families to develop organically. The coding families were developed, connected and located using the broader conceptual framework of Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017). For example, the neighbourhood and community domain helped organise the code families concerning changes in landscape, experiences of migration and social cohesion (see Table 1). Similarly, using the other domains from this framework, we unite disparate evidence to contextualise the history of the place, the dynamic reciprocal relationship between place and ageing, and distal outcomes, such as access to health care and employment services. Though not all domains remain applicable (e.g. civic participation), the model offers a structure for our empirical evidence, and our findings help add newer elements to the relevant domains.

Table 1. Code families and themes emerging from coding of in-depth interviews and behavioural mapping and their relations to the old-age exclusion framework of Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017)

Results

Emergence of the periphery: neighbourhood and communities

Anjanapura was originally a village with agricultural fields and quarries, and bordered by a wildlife sanctuary. Owing to a gradual expansion of Bengaluru, the erstwhile village was incorporated as the 196th ward of Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP or Greater Bangalore Municipal Corporation) in 2007. People who earlier inhabited a village now found themselves a part of the city. Understandably, older adults found it odd to be asked the reason for settling in the neighbourhood. They quickly retorted, saying, ‘it is our village’, ‘I am here from birth’, ‘my ancestor's house’, ‘my in-law's house’ and questioned in turn ‘why should we settle anywhere else?’ Men usually referred to their tangible assets, such as agricultural land holdings and ancestors' houses, as reasons for residing there. An older man, remembering his agrarian land, said, ‘it was here (pointing towards now a plot of houses), it went off to BDA [Bangalore Development Authority]. We did not get money’. Most older women were associated with multiple spells of migration to and from the neighbourhoods for marriage since patrilocal living arrangements are traditionally the norm in India. Many women had migrated for marriage to their spouse's house in Anjanapura three to four decades earlier (see the Appendix) from other sub-urban places such as Kengeri, Kanakapura, Sarjapura, Hoskote and Chikkaballapura. A few women had married out of the area, but either due to separation or widowhood, they had returned to their natal village, Anjanapura, with their children.

Migrant older adults reported that they had aspirations of residing in the ‘city with nice neighbourhoods’. However, the lack of secure jobs in the city, unaffordable housing and landlords not renting houses to ‘outsiders’ made them settle on the periphery. For instance, Chandrashekar, working in a hotel, tried to find a home to rent within the city. He found it difficult to understand the new renting regulations in the city, and he explained how landlords rented only to people they knew. He then settled in the periphery 15 years ago and now pays a monthly rent of INR 1,500 (approximately US $20) to live in a thatched house. Sudhamma, an older woman separated from her husband, said the lack of daily wage work within the city made her relocate with her ailing mother and two children to the peripheral ward. The long-term residents were cautious of other households that had moved into their neighbourhoods from the city, searching for affordable housing. For instance, Parvathamma lamented the entry of persons from north Indian regions and blamed them for increasing inter-community marriages. Despite their neighbourhood being officially within the city boundary, older adults still saw their ‘village’ as part of a cultural frame and the city as the other. The migration of vulnerable groups to these peripheries, though perceived by natives as diluting their placed-based identity, created a liminal space between urban and rural for those who could not fit into the city.

Older migrants were enthusiastic about the new shops in the neighbourhood where they could buy ‘A to Z’, i.e. anything they wanted, and the rise of tall apartment buildings. They often referred to how their village has reached the ‘city level’ since it became included within the corporation limits. In comparison, earlier inhabitants lamented the loss of the Gram Panchayat (local administrative unit of a village) system and opposed the centralisation of civic services. Shankrappa, who was earlier a Gram Panchayat member, said:

BBMP has not done anything. See this road; the tar is not laid even after one year. What will they do? Panchayat could have worked on roads better. I would have helped.

Liminality lies in the ambiguous identity of this transitionary space between an urban ward and a rural village. Being on the margins of the urban administration but having lost the rural civic networks meant that transport services suffered. Older adults bemoaned these changes, explaining their everyday interactions with these ambiguous and insufficient infrastructures. They reflected on the developments in the local economy that have brought sweeping changes in the built-up environment, thus affecting their material resources. They referred to the loss of lush-green agricultural fields they used to work in due to land acquisition by the BDA to construct housing layouts and the Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board to build peripheral ring roads (see Figure 1). On the other hand, older women consistently referred to the benefits of some of the new factories set up in the periphery. Many older women used to work in these manufacturing units, primarily in garments and bottling plants. For example, Shivamma, an older woman and a former employee of a liquor-manufacturing factory, credited the factory owner (name changed) for building a temple and influencing the first bus route to the village:

After Giri sir [proprietor] bought these agricultural lands, they built the temple. Then there wasn't even a bus to this road (another older woman nods in agreement). After Giri sir opened his factory, the bus also came. Everything improved.

The introduction of public buses in the early 2000s was referred to as a landmark change, which catalysed changes to the neighbourhood, including its name from Hollankere (old name) to Anjanapura (its present name). Though many spoke of changes, older adults also pointed to the economic and social spheres that remained, such as the rearing of domestic animals and practice of extended families residing on the same streets in a community. During the interviews, older women talked about congestion in the streets, pointing to the ward's narrow concrete alleys, people sitting about on sidewalks, clothes washing in the open street, and courtyards frequented by the hens, cows, dogs, cats and goats. Often, the older women were tending to these domestic animals during our interviews. The neighbourhood and changing notions of the community reflect the making of liminal zones with moments of continuities and discontinuities, constantly negotiating between the social order of village society and the uncrystallised new value order of an urban milieu.

Ageing disadvantages in a socio-economic hierarchy: declining resources

Despite the region being inducted into the administrative border of the city, traditional social hierarchies of caste and religion remain and contribute to a sense of liminality in the neighbourhood. Access to civic amenities was determined by spatial positioning in the periphery, which is fixed by one's caste and faith in the community. As an older adult, Parvathamma observes, caste-based residential segregation such as Edagai Footnote 7 (left-hand Dalit castes) and Balagai (right-hand Dalit castes) and not encouraging cross-caste property sales was still a norm in the neighbourhood. While the Balagai houses occupied the corner real estate facing the main road, the Edagai houses were inward-facing and away from the bus stop. Similarly, Muslim households were situated away from main roads, stacked closely with shared walls and surveilled by police CCTV cameras (witnessed during behavioural mapping). Older adults from Scheduled CastesFootnote 8 explained how Vokkaligas,Footnote 9 who historically owned agricultural land in the region, benefited from state-led land acquisition. Agricultural labourers, mostly from Scheduled Caste groups, and Muslims, who worked in these fields, were left unemployed and uncompensated following the land acquisition. Additionally, Vokkaliga houses situated on wider streets, secured more public water taps, and had better access to main roads and a higher number of streetlights. On the contrary, the ‘SC [Scheduled Caste] streets’ (as they were referred to) were often narrow, had fewer taps and streetlights, and were usually far from the bus stop.

Most households that were interviewed consisted of older adults, sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren living in highly cramped housing conditions. Many older adults just had a cot earmarked for them. They recollected how ‘Indiramma’ (Indira Gandhi), India's ex-prime minister, had sanctioned these homes for Scheduled Castes in the 1970s. These houses, built incrementally with state assistance, currently lay unpainted, were dilapidated due to rains, and were situated in narrow and uneven alleys, where even scooters could not enter. Mohamad Ashraful described his poor housing condition in a narrow alley with Muslim households as ‘congested, no place even to walk … no air [no ventilation]’.

Furthermore, the economic condition of older adults deteriorated over time with changes in the local economy. Older adults who had cut stones in nearby quarries, carried bricks for brick kilns and helped in glass factories were laid off after these industries underwent closure ‘due to environmental concerns’. As a result, many older persons who had learned skills to work in these fields were out of work. Poverty because of lack of basic income emerged as a strong theme across all sub-groups of older adults. For example, Sudhamma, an older woman who works as a daily wage labourer due to irregular work availability, has not been able to pay rent, buy groceries or afford cooking gas. Sobbing, she says she has instructed her son and daughter to have their meals in their workplace. Those who desired to work were struggling to find a suitable job in the neighbourhood. Chandrashekar, who used to work as a security guard, lost his job due to gastrointestinal illness. After recovery, his bus journey to Banashankari (approximately 5 miles) was difficult due to fatigue. Since then, he has been searching for a security guard job close to the neighbourhood but has not succeeded yet. Older adults (75 and above) who could no longer be part of the workforce depended on the old-age pension provided by the Karnataka government under the Sukhanya Samruddhi Yojana. Participants of the scheme reported struggles with obtaining the pension which involved red tape, the insufficient pension amount of INR 950 (approximately US $13) per month, irregular disbursement ranging from two months to one year without payments, missing arrear payments and high processing charges of INR 50 (approximately US $0.60) each month. This pension amount was used to buy medicines, bus tickets or sometimes betel leaves.Footnote 10 In the months that they do not receive a pension, they reduce their bus trips and, in turn, are less able to get to work or receive medical attention. This precarious economic condition is illustrated in the narrative of Zakir Khan, an older adult and owner of a small shop. He laments that he has not received a pension for his wife despite the possession of a pension card:

She is not getting [pension]. We had got it done for her as well, it is not coming. It has been March, one year, the pension has not come. We have spent 3,000 rupees to get it [pension card] done … Card and all we have then it [pension] did not come. If it comes, it will come for one month; then it won't come. Sometimes it won't come for two months … Someone comes with the pension. They take 50 rupees and give 950 rupees to us. No, they won't pay [arrears]. They have not given any [phone] number.

Across all ages, older adults struggled to get a stable income and were financially dependent on their children for their essentials. Almost all older adults lived with their sons and a few with their daughters. They recognised the inability of children to support them since the children also worked in low-paying informal jobs. However, this dependency also resulted in familial discord and elder abuse in a few cases. For example, Zakir Khan experienced verbal and physical abuse from his daughter-in-law and son. During the interview, he pointed to his broken tooth resulting from the altercation. Since then, the son, who owns an auto-rickshaw, demands exorbitant fares from his parents for help with hospital visits. This is how the older adult recollected his experience tearfully:

My son drives an auto [rickshaw]. For taking us on auto for two days, he charged us 1,000 rupees [approximately US $13] as rent. Two days he took his mother to the hospital and charged us 1,000–1,200 [approximately US $13–16].

Additionally, ageing-related physiological changes such as decreased muscular strength, increased fatigue and higher vision impairment made it difficult for older adults to work. Siddalingaiiah used to work in a nearby quarry as a goods vehicle driver. Due to his cataract condition and successive stroke, he had to quit driving. He has been struggling to pay rent and is economically dependent on his elder daughter, who works in a printing press. In another case, Sadia Sultana, an older woman with a high level of visual impairment, who owns a small shop on the Scheduled Caste street, finds it increasingly difficult to travel by bus to the city market to buy goods. Instead, she asks her brother-in-law to purchase goods. Due to fatigue, she cannot even walk home, hence sleeps in the shop in the afternoon. She closes the shop early before dark as she finds it difficult to navigate the dark streets with insufficient streetlights. Physical debility, particularly impaired vision, combined with poor street lighting in the neighbourhood, restricted older adults' mobility and, in turn, their economic opportunities.

Incidentally, all older women interviewed had lost their spouses. Almost all women attributed their spouse's early demise to excessive alcohol consumption, which they say is widespread among men employed in manual labour in the neighbourhood. Kumar's (Reference Kumar, Martin, Chungkham and Ladusingh2017) research on the manual scavenger community in India reports a similar trend of early morbidity of manual labourers working in ‘uncomfortable and harmful working environments’. Much of their narratives pointed to the deterioration of their economic condition and constrained mobility since the death of their spouse. Padma, an older woman who lost her husband, expressed helplessness due to her immobility:

When my husband was there, he would take me. I feel if he was there, he would have taken me around. Helped me. It is human to feel that pain. If at least he was there, he would have shown me different places (sobs). What else can I say at this age?

The intersection of the multiple identities led to the multidimensional disadvantage that is frequently enmeshed in socio-economic precarity. Older persons were further pushed towards poverty, social isolation and limited mobility by these place-based political economy shifts and historical imbalances.

Restricted mobilities: reducing access to service and amenities

The mobility needs of older adults were largely related to health care and participation in the labour market (see the Appendix). Research participants experienced severely constrained mobilities and unmet needs. Our evidence illustrated that ‘transport disadvantage’ emerged from an intersection of micro-level factors (individual's social disadvantage) and meso-level factors (neighbourhood's transport infrastructure). Older adults were less independent and could access fewer transport modes with age. Car and scooter ownership was rare; even in cases of ownership among older men, they experienced driving cessation after a crash. Mohamad Ashraful used his trembling fingers to point to stitches on his forehead when asked about his scooter. He recounted an incident which occurred while riding his scooter near Tipu Circle (Figure 1) when he did not notice a speed breaker, resulting in a crash, injuring his head and requiring multiple stitches. Since then, he has never used his scooter again. The shorter neighbourhood trips for daily errands, also a social event to meet neighbourhood acquaintances, were no longer possible after the driving cessation.

Given that the ward is peri-urban, long trips and multiple bus changes are necessary to access hospitals, work and markets in the city. Participants said the public bus is a regular lifeline for workplace trips (4–10 miles), hospital and city market visits (10–15 miles), and much longer trips (20 miles and above) to visit their native villages in the city's suburbs such as Kolar, Kanakapura, Hosur and Anekal. Chandrashekar, a security guard, recounted how he struggles to afford bus fares with his low and irregular income as he is not eligible for a senior citizen bus pass.Footnote 11 Gowramma, who receives a miserly INR 950 (approximately US $13) as a pension, replied to our question on affordability as follows:

Can we go and come with this ticket price? … We need to have at least 100 rupees to go and come. Who will give us money? That pension comes once in three months; if they have to give for two months, they only give for one month and will not give the other month. Same way, if they give this month, they won't give next month. That woman [pension delivery agent] will take 50 rupees commission from 1,000 rupees pension. For how long do you spend it? For how many days will it be sufficient?

Physical challenges to using buses increase at later age. Gowramma regularly travelled by bus to work as a Pourakarmika (waste management worker). As we observed during behavioural mapping, due to knee pain, she had to be lifted by a male bystander to board the steep steps of the bus. Sadia Sultana explains how the bus personnel help her with her heavy luggage: ‘conductor or someone would help us unload it [luggage] here’. Such micro assistance from street vendors, bystanders and co-commuters from ‘their village’ help older commuters in accessing markets for business and hospitals for health care. However, crowding in buses means that finding a seat is difficult and one has to travel standing. Similar physical challenges in the Bangladesh context have been identified by Jahangir et al. (Reference Jahangir, Bailey, Uddin Hasan, Hossain, Helbich and Hyde2022).

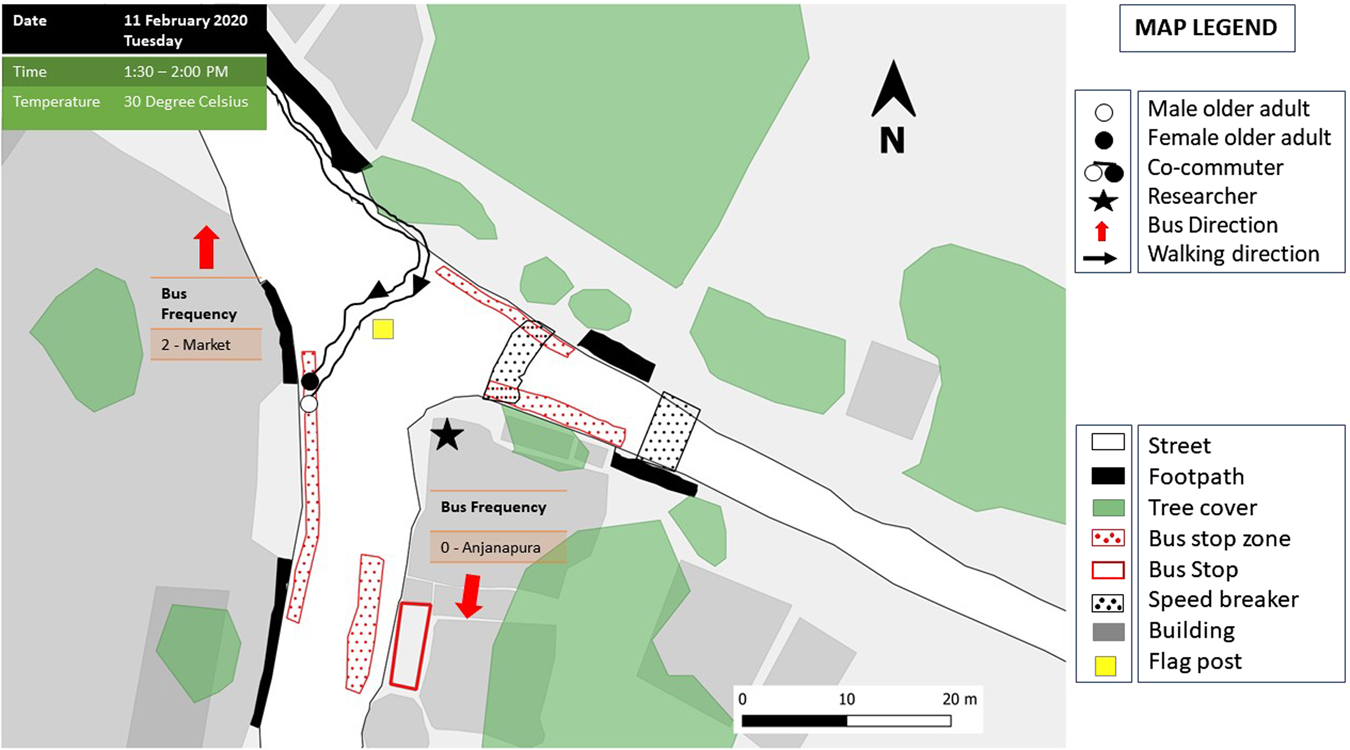

Poor facilities for bus users at the peri-urban bus terminals was a major barrier for participants' access to public transport. We provide an example below where we met an older couple on their way towards the city market for a medical visit to diagnose the cause of a chronic stomach ache experienced by the woman (Figures 2 and 3). That summer afternoon, they were standing in the shade of a factory's compound while awaiting the bus (Figure 2). During the interview, they spoke of the short travel window that they have, as mornings and evenings are peak hours and buses are crowded, and post-sunset travel would be difficult due to visual impairment. They pointed to the only bus shelter (Figure 3) where an older man with a drunk appearance was sleeping on the seat earmarked for waiting passengers. While conducting the behavioural mapping exercise (Figure 3), we identified and mapped the different elements of physical infrastructure that restricted the mobilities of these two older commuters (Figure 2), such as limited waiting and seating arrangements, poor pedestrian infrastructure and the incessant weather conditions.

Figure 2. Older adults seeking shelter while waiting for a public bus.

Source: Author.

Figure 3. Behavioural mapping depicting the environmental setting of older adults awaiting a bus, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: Author's representation.

Despite challenges, participants were more familiar and thus confident with the traditional bus system. For example, Parvathamma, an older woman with no formal education, felt commuting to Majestic (a major city junction) 10 miles from Anjanapura was as easy as ‘drinking water’. On the other hand, many feared using the Metro rail due to ‘fear of falling’ and difficulty in climbing to reach the station. Sarvamangalamma explains her experience as follows:

One day, my grandson took me in it [elevator]. It was turning like this, I went up, and I almost fell off [referring to elevator]. That was the only time I went (continues to chuckle). I went up, and my grandson was down, then someone helped me get down.

Metro rail and ride-hailing services such as Ola and Uber were not preferred options as the fares were ‘unaffordable’ for longer trips from the periphery. Besides, they did not consider these new modes of transport that came up in the cities as ‘theirs’. Older adults remarked that such modes were only meant ‘for officials’ and ‘for people living in apartments’.

Alongside intermixing of population and traditional caste hierarchy, the Dalit and Muslim residents of the neighbourhood relied on community help as a safety net. ‘We feeling’ is embedded in such community-arranged trips to places of cultural significance. For instance, one of the key informants, a Dalit leader, explained how the caste association arranges free trips for Dalit residents, mostly older adults, to visit Bhima KoregaonFootnote 12 (530 miles away) for the annual congregation. Further, community associations also played a vital role in older adults commuting during medical emergencies. The local Schedule Caste association and the local Masjid funded the purchases of auto-rickshaws for the community. These vehicles were earmarked for medical emergency trips. In a recent case, one night, an older woman living in the Scheduled Caste alley had a seizure and required immediate medical attention. An auto-rickshaw driver (proudly) recounted that the older woman's family called him instead of an ambulance on that night. He quickly took them to multiple hospitals in the city. After travelling close to 15 miles and being turned away by two hospitals, he finally managed to get her admission to a hospital. Then the auto-rickshaw driver stayed in the hospital until morning. Unfortunately, the older woman succumbed due to medical complications and passed away. In such medical emergencies, the auto drivers, mostly neighbours, did not charge fares and referred to them as ‘our village people’, ‘our caste/religion people’ and not passengers. Such informal support mechanisms were crucial for the occasional or emergency mobilities of vulnerable social groups. However, regular transport to work or daily errands remained unsupported.

Overall, the public bus remained a lifeline connecting older adults to the ‘city’ amidst peri-urban space's poor public transport situation. Occasional help from informal social networks temporarily patched their transport disadvantages.

Restricted mobilities leading to exclusion in later age

Restricted mobilities intersected with other disadvantages to exclude older adults from accessing essential services and opportunities in the ‘city’. From the behavioural mapping exercise, we found that the poor quality of the public health facility in the peripheral ward forced older adults from low-income households to visit larger government hospitals such as Jayadeva Hospital (4 miles), Sanjay Gandhi Hospital (6 miles) and Victoria Hospital (9 miles) located in the core city for medical attention. Such journeys were characterised by longer commute time, multiple bus changes, and expensive first- and last-mile transport options.

The developments in the local economy and the inaccessibility of mobility options in the neighbourhood reduced access to economic ‘life chances’. Older adults found public transport unaffordable for regular runs to the city for work, thus limiting them to employment closer to the periphery. Chandrashekar, a security guard, says the monthly bus pass is unaffordable as his employer pays him sometimes on the 18th or 20th day of the month. In contrast, an older adult who uses a senior citizen bus pass to visit the market once a week to buy goods for their shop does not mention unaffordability. Often, older adults struggled to withdraw their pension from the post office or bank, as they found these multiple trips within the neighbourhood tiresome. The inability to access employment opportunities and restricted access to social security benefits push many into a poverty spiral. Multiple narratives illustrate the low self-esteem older adults develop with lowering economic abilities. Chandrashekar says:

Even their own kids won't talk to them. Many sit here and there and spend time. Somehow, they might get two meals per day. That is all they will get. If they have saved money for themselves, they will manage. These wage workers work hard and bring up their kids. Their kids will turn into drunkards and go away and won't look after them. Avara paadu naayi paadagiratte [Such parents' lives will be like dog's].

Later-age social participation waned and was limited to the neighbourhood as mobility decreased with age. Older adults frequently needed assistance when visiting family deity temples, native villages in the suburbs and weddings. Gowramma, an older woman, attends social events only when her son or relatives arrange for a bus or van. Older women's movement for social events was drastically reduced after their spouse's death. Virtual socialisation was low as smartphones were unknown. Apart from one older man from a dominant caste, who used a non-android basic phone to talk to his friend, no other older adult owned a cell phone. In rare cases, grandchildren helped their grandparents talk to their family members using borrowed phones.

Streets in front of the house, shops and tea shops, often away from the main roads, were where an older adult socialised. High visual impairment, poor access to mobility aids such as spectacles or walking sticks, combined with insufficient street lighting created unsafe walking conditions after dark. Sarvamangalamma, an older woman (with high visual impairment) who lives on the ‘Muslim Street’, recounts how she fell and fractured her hip bone while walking in front of her house at night. Since then, she returns to the house by 6 pm and does not venture out until it is bright the following day. Brief periods after sunny afternoons and just before dark, those evening walks through the narrow streets were a major socialisation opportunity for older women. Sarvamangalamma and Gowramma walk together daily, sit on a broken wooden plank near the petty shop, eat betel leaves and talk to each other. While asking about their walks, they begin joking that they are 25 and 30 years old and will not fit our research criteria.

Older adults are already experiencing socio-economic vulnerabilities; the physical ageing process added to their risks of isolation. The centralisation of essential services and transport disadvantages within the neighbourhood further restricted their social relations. Socio-economic marginalisation, ageing-related challenges and poor civic services have constantly produced precarious ageing experiences on the periphery:

While dying, we should die the same. We should earn and feed ourselves. Once we die, someone like you will do our final rites. (Zakir Khan)

Take me, take me (louder). I cannot do anything now, I am not helpful to anyone, I can't help. Why should I be around? That is my situation (starts sobbing). If I tell my situation, you will make a film about it. That is the situation I am in. (Shivamma)

Discussion

This paper contributes to nuances in the understanding of what it means to age in LMIC, especially in urban peripheries that are often not visible but house a large number of disadvantaged and marginalised groups. The results bring attention to these particular groups and an understanding of the inequalities arising from exclusion from a later-age perspective.

Ageing in neighbourhoods with uneven peripheralisation

The changes in the political economy of the neighbourhood owing to peripheralisation have had multidimensional consequences for ageing. The neighbourhood context and its socio-political structures emerged as the most crucial domain in the old-age exclusion model (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017; Walsh, Reference Walsh, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018). The study area witnessed visible transitions in the built environment from an agrarian village to an urban ward. Insecurity and the anticipation of an uncertain future in these unknown liminal spaces were embodied in the narratives of ageing. Such changes in the environment invariably do not take account of ageing and are also not interpreted from an exclusionary lens (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017). Our results point to the ‘uneven’ urbanisation in the peripheries from an ageing perspective, similar to Bartels et al. (Reference Bartels, Bruns and Simon2020). The betwixt and between processes ‘alienated’ older adults from what they consider their ‘native’ village as well as the migrants who came in search of new homes. Degenerative peripheralisation is not exclusive to India but has been rampant in other global South countries, such as South Africa, Brazil and Mexico (Venter et al., Reference Venter, Mahendra, Lionjanga, Mulley and Nelson2021). The micro-narratives of later-life poverty, unemployment and ill-health in these fresh patches of urbanisation need to be researched in relation to the larger currents of urbanisation. Geographical gerontologists must be cognisant of the dominant trends of the rise of peripheries and ageing settlements on these topographical fringes. The LMIC context of poor state capacity (inadequate social security and civic infrastructure) and increased private enterprise can result in ‘speculative urbanism’ (Goldman, Reference Goldman2011). This can rapidly snowball to create individualisation of risks for resource-poor older adults when accessing amenities and services and avoiding exclusion.

Traditional hierarchies and inequalities in later age

Ethnic hierarchies of caste and religion permeate social relations and can ration access to services, amenities and mobilities resources, further increasing exclusion in later life. In line with extant literature (Andrews and Phillips, Reference Andrews and Phillips2004; Bartels et al., Reference Bartels, Bruns and Simon2020), we found that historical processes in the periphery intensified traditional power relations and amplified inequalities in access to transport, health care, housing and employment. In contrast to the physical environment, the social structures of the society (e.g. caste system, social norms, cohesion) remained rigid. Despite rapid urbanisation, the traditional social hierarchies of caste and religion were crucial in determining access to land, housing and civic amenities. Remaining on these territorial and cultural margins, older adults, mainly from Schedule Caste and Muslim households, lived at the intersection of ageism, material poverty and area-based exclusion. In addition to topographic margins, migrant older adults find themselves at cultural margins, unable to adapt adequately (Shields, Reference Shields1991). Our study adds to the evolving literature (Upadhya and Rathod, Reference Upadhya and Rathod2021) on the subaltern struggles and contestation for urban services in the traditional peri-urban zones of LMICs. Globally the themes of oppression experienced by older residents can extend to other forms of ethnicity, such as racial, linguistic or regional. We highlight the processes of hierarchical social structures in these urban liminal zones that impact older adults' wellbeing.

Conversely, our findings also highlight that community consciousness and social capital act as safety nets for older adults in times of adversity, such as when there is a medical emergency. We build on Turner's (Reference Turner1979) work to highlight the crucial role communities play in arranging informal social networks in resource-poor liminal spaces for older adults to stay mobile. Studying the community within this hybrid peri-urban context is essential to understanding how older adults cope, navigate and age in these liminal spaces.

Subsistence needs, restricted mobility and isolated ageing

The rise of peripheries centralises health-care and municipal services, placing undue pressure on marginalised groups, e.g. older adults, to commute longer distances (Venter et al., Reference Venter, Mahendra, Lionjanga, Mulley and Nelson2021). Despite having basic needs to be mobile and access civic amenities, these needs remained unmet in these ‘institutionalised liminal zones’ (Shields, Reference Shields1991). Poor transport facilities and lack of access evaporated opportunities to work, access health care and enjoy social life, and produced a cyclical precariousness (Lucas, Reference Lucas2012; Meijering, Reference Meijering2021; Venter et al., Reference Venter, Mahendra, Lionjanga, Mulley and Nelson2021). Inadequate transport infrastructure in the periphery, particularly public buses (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite2017; Jahangir et al., Reference Jahangir, Bailey, Uddin Hasan, Hossain, Helbich and Hyde2022), adds to older adults' vulnerability in being mobile. Ageing-related declines in health, particularly bodily aches and greater visual impairment (Barman and Mishra, Reference Barman and Mishra2021), negatively impact health care, participation in the labour market and social activities (Musselwhite and Curl, Reference Musselwhite and Curl2018). The findings become relevant given the pandemic lockdowns in developing countries that accompanied paternalistic advice for older residents. The shutdown of public transport and restrictions on neighbourhood mobility confines older adults to their already-cramped houses. Existing issues of unemployment, delayed treatment and social isolation in countries with limited social security could turn into chasms (Munshi et al., Reference Munshi, Sankar, Kothari, Curl and Musselwhite2018). Whilst we are examining one specific space, our findings are relevant for cities of LMICs with non-age-inclusive transport infrastructure and are designing policy interventions to address the fundamental Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of providing decent work (SDG 8), health care (SDG 3) and sustainable cities (SDG 11).

Exclusion in later age: the perils of homogenous urban planning

Overall, the rise of peripheries has accompanied real-estate expansion with infrastructure that is not supportive of active ageing. Older adults living in the intersection of topographic and cultural margins lead isolated, immobile and subsistence lives, which pose more questions for social policy than answers to their everyday ageing predicaments. Given that peripheral urbanisation is pervasive in many cities of the global South (Caldeira, Reference Caldeira2017; Venter et al., Reference Venter, Mahendra, Lionjanga, Mulley and Nelson2021), the everyday experiences of ageing within these patchwork streets will require renewed attention from global frameworks such as the guide to age-friendly cities. We urge that place-based policy be an integral part of age-friendly cities and draw evidence from context-specific qualitative research (e.g. Barman and Mishra, Reference Barman and Mishra2021) emanating from the global South. For instance, in line with Mehta (Reference Mehta2009), our findings emphasise the ways in which streets are the last few remaining meaningful public space for entertainment and communication for older people living in these peripheries. Urban planners need to venture beyond the economic lens and mega infrastructures to understand fully the risks of marginalisation on these increasingly distorted streets. Social policy that aims for age-friendly cities requires a more nuanced understanding of space and place and their impact on ageing. Gerontological research should depart from the neat categorisation of rural and urban. The liminal confusions of the rural–urban continuum in places such as Anjanapura cautions us against the oversimplification of urban in age-friendly environments.

Limitations

While exploring the knowledge claims from this paper, there could be a few limitations, primarily that the study participants are from low-income and marginalised social groups. Most participants belonged to Muslim and Dalit households, worked in the informal sector and had lived in the space for at least a decade. We did not engage with many older adults, retired from formal jobs or businesses, and settled in the gated communities of Anjanapura. Therefore, the results should not be generalised to other socio-economic categories among older adults within the peri-urban region. However, given the prevalent issue of low-resourced ageing on urban peripheries in LMICs, these results can apply to such cities.

Secondly, the paper's scope does not allow for a cross-generation comparison. The experiences of exclusion and inclusion for different age groups on the peripheries may differ or remain similar. However, there is limited comparative evidence to conclude either. Further, the study is reflexive of the risks of the ageist association between social exclusion and later age. Hence, we cannot conclude that exclusion is only or highest among older age groups. The study, in line with recent research (Naughton-Doe et al., Reference Naughton-Doe, Barke, Manchester, Willis and Wigfieldin press), steers clear of such ‘moral panic’. We have juxtaposed older adults' exclusion and mobility barriers with negotiations, coping mechanisms and resilience on these city margins. We believe future research in geographical gerontology has the scope to undertake relative experiences of living and mobilities on these urban margins across different co-existing generations.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding these limitations, the paper provides empirical geographical insights about the ways in which place intersects ageing processes in LMICs. The findings demonstrate what living in topographic and cultural margins on these peripheries entails to ageing, mobility and risks of exclusion. These peri-urban liminal spaces are the buffer between completely rural and urban lives. These are also essential places where marginalised and inexpensive labour resides. The multidimensional framework (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017) helped connect the cross-cutting themes and explain how socio-economic, historical and spatial inequality coalesces to create exclusion at later age. Neighbourhood context and restricted mobility have had wider ramifications for ‘ageing in place’ in peri-urban space, while domains such as civic participation were perceived as less of a priority by older adults. Although we recognise that not all older adults in the city face similar challenges, it is imperative to identify the struggles of these vulnerable older adults who fall into the gaps by living in these peripheries. This paper suggests that given the ageing of the population and increasing peripheralisation in LMICs, the precariousness of immobile ageing on urban fringes requires renewed attention from research and policy circles.

Author contributions

PN: conceptualisation, methodology, software, resources, field work, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualisation, supervision, funding acquisition. AB: conceptualisation, methodology, resources, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. SG: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. MH: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. LS: conceptualisation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, supervision.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO); Utrecht University, The Netherlands; and the University Grants Commission of India (Junior Research Fellowship). This work is part of the research project ‘Inclusive cities through equitable access to urban mobility infrastructures for India and Bangladesh’ (principal investigator: Prof. A. Bailey) under the research programme Joint Sustainable Development Goal research initiative (project number W 07.30318.003), which is financed by the NWO and Utrecht University, The Netherlands.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Table A1. Demographic profile of older adults who participated in in-depth interviews