Introduction

In Mediterranean countries the analysis of intergenerational solidarity has generally focused on the family, at times excessively (Calzada and Brooks, Reference Calzada and Brooks2013), both when a comparative approach is used (Reher, Reference Reher1998; Calzada and Brooks, Reference Calzada and Brooks2013; Bordone et al., Reference Bordone, Arpinio and Aassver2017; Vergauwen and Mortelmans, Reference Vergauwen and Mortelmans2019) and when studying specific cases, such as Spain (Ayuso, Reference Ayuso2012; Marí-Klose and Escapa, Reference Marí-Klose and Escapa2015; Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, López and González2019; Meil, Reference Meil2000). To date, in these countries it has been common to observe a high degree of family-based intergenerational support – such support is sometimes less frequent but more intense than in countries with a social-democratic welfare system (Marí-Klose and Escapa, Reference Marí-Klose and Escapa2015) – especially in the form of care-giving relationships (Meil, Reference Meil2011), particularly parents–children and grandparents–grandchildren (Hank, Reference Hank2012). Considerable effort has been made to explain the flow of this solidarity when it involves the oldest family members (Kalmijn and Saraceno, Reference Kalmijn and Saraceno2008; Da Roit, Reference Da Roit2009; Bazo, Reference Bazo2012; López et al., Reference López, González and Sánchez2015).

Mediterranean countries are also showing clear evidence of demographic ageing (Marcaletti et al., Reference Marcaletti, Iñiguez-Berrozpe and Garavaglia2020). For example, in Spain the proportion of persons aged 65 and over in the total population reached 19.2 per cent in 2018 (Eurostat, 2019a), close to the European Union average; a decade earlier this was 16.4 per cent. In addition, in 2018 Spain's rate of dependency, which is similar to the European rate, was 29 persons over the age of 65 for every 100 persons of working age (Eurostat, 2019b); however, projections foresee a ratio of 49.4 persons over the age of 65 for every 100 potentially working persons – between 15 and 64 years – in 2040 (Eurostat, 2019b). In addition, the fertility rate is at a historical low (FBBVA, 2019).

The increase in life expectancy – 86.2 years for women and 80.9 years for men (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), 2019a) who reside in Spain – is another of the reasons that explain the country's demographic ageing. It is precisely this increase, along with low rates of infant mortality, that has given rise to a historically new phenomenon: the co-existence, both inside and outside the family setting, of a high number of different cohorts and generations at the same time. However, there is no reason to presume that such co-existence is bringing with it more contact among the generations or greater intergenerational solidarity. For example, it has been shown that when population ageing is accompanied by a decrease in age integration or intergenerationality (Uhlenberg, Reference Uhlenberg2000), contact and solidarity can diminish at both intrafamilial and extrafamilial levels. It therefore makes sense to ask how patterns of intergenerational solidarity – inside and outside the family – are affected by the degree of intergenerational contact and integration of a multigenerational society that is experiencing significant demographic ageing, a topic rarely addressed in the literature (Vanderbeck, Reference Vanderbeck2007; Baykara-Krumme and Fokkema, Reference Baykara-Krumme and Fokkema2019; Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Whetung, Kruchten and Butts2020).

Intergenerational solidarity, inside and outside the family

In countries considered to have a high degree of familialism, such as Spain, care-giving between generations has traditionally been associated with the family setting. Albertini and Kohli (Reference Albertini and Kohli2013) pointed out that many of the studies that look at family wellbeing and relationships have focused on the informal care networks existing in these countries, the structural characteristics of which are well known (Lowenstein and Katz, Reference Lowenstein, Katz, Dannefer and Phillipson2010). It is also known that both physical, or instrumental, support between generations which is influenced by geographical proximity, and emotional support which depends upon the possibilities for contact, are linked to these societies’ family norms and obligations (Saraceno and Keck, Reference Saraceno and Keck2008). How such family norms and obligations are institutionalised shapes, implicitly and explicitly, the predominant forms in which support is provided. It also explains the establishment of different welfare policies (Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Brandt and Haberkern2012) and determines, to a great extent, the format of the relationships between generations.

All of this suggests that when a country in which familialism predominates not only experiences changes in its demographic situation – due to progressive ageing – but also, as a result, sees a transformation in the rules governing the contact and relationships between generations, it may be even more necessary to look beyond family boundaries to understand fully practices of intergenerational solidarity. Working with the premise that intergenerational solidarity is not exclusive to the family setting (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, García, Díaz and Duaigües2011), the present study intends to take this step of exploring empirically this connection between the intra- and the extrafamilial realms of contact and intergenerational solidarity at inter-individual and family levels.

Dimensions and levels

The concept of intergenerational solidarity refers basically to social cohesion among generations (Bengtson et al., Reference Bengtson, Olander, Haddad and Gubrium1976; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Richards and Bengtson1991; Katz et al., Reference Katz, Lowenstein, Phillips, Daatland, Bengtson, Acock, Allen, Dilworth-Anderson and Klein2005). The literature about intergenerational solidarity has developed largely around the six dimensions that Bengtson and Roberts (Reference Bengtson and Roberts1991) proposed originally for the intrafamily setting: associational (type and frequency of contact), affectual (type and degree of positive sentiments among members of the family and the degree of reciprocity of such sentiments), consensual (degree of agreement in terms of values, opinions and orientations among family members), functional (mutual social support and assistance, understood as exchange of resources), normative (strength of commitment to meet family obligations and comply with norms regarding the importance of values associated with the family) and structural (geographical distance or structural opportunity for intergenerational interaction within the family). These six dimensions have been used on many occasions in the literature as a means for exploring how intergenerational solidarity within the family works (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2011; Hank, Reference Hank2012; König et al., Reference König, Isengard, Szydlik, Česnuitytė and Meil2019).

More recently, Bengtson and Oyama (Reference Bengtson, Oyama, Cruz-Saco and Zelenev2010) have proposed that two levels of analysis of intergenerational solidarity and conflict be distinguished: macrogens – the societal and group level, for example, among age cohorts; and microgens – the family and individual level. As for the micro level, most studies conducted on intergenerational solidarity focus on the family context rather than the non-family context (Butts, Reference Butts, Cruz-Saco and Zelenev2010). In contrast with this tendency, the present paper defends the need to investigate the possible connection between the two contexts in times of increased demographic ageing (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, Sáez, Pinazo, Cruz-Saco and Zelenev2010). For some time now this idea has been put forward as a recommendation to keep in mind when designing public policies, for pragmatic reasons: bridges between familial and non-familial relationships should be established, as this will allow the mobilisation of resources to respond to various needs of different generations (Cruz-Saco and Zelenev, Reference Cruz-Saco, Zelenev, Cruz-Saco and Zelenev2010: 225).

In fact, arguments in favour of collaboration between the field of family studies and that of intergenerational studies – which pays close attention to extra-family community contexts – are nothing new. Some scholars have gone so far as to suggest specifically that some of the intergenerational solidarity patterns observed in families – e.g. in relation to care-giving – be replicated and compared with the behaviour observed in non-family situations (Hans and Ponzetti, Reference Hans and Ponzetti2004). However, little progress has been made in this area to date.

Application outside the family

While it is true that the theoretical model developed by Bengtson and Roberts (Reference Bengtson and Roberts1991) has had a greater echo in the explanation of intergenerational solidarity within the family, the demographic changes discussed above – especially growing multigenerational co-existence – do raise new questions. One such question is whether these dimensions could also be applied to relationships between individuals of different generations without kinship ties. Some researchers have already attempted to tackle this issue.

For example, Gonzales et al. (Reference Gonzales, Whetung, Kruchten and Butts2020) posit that intergenerational transfers also occur outside the family setting. These authors also speak of the potential of intergenerational solidarity to improve our comprehension of non-familial intergenerational relationships. In their work, they integrate the model of intergenerational solidarity with the productive ageing framework in the context of home sharing, so as to be better prepared to evaluate intergenerational home-sharing programmes:

Integrating intergenerational solidarity theory with the productive ageing framework in the context of home sharing enables us to consider the quality and kind of relationships that exist between individuals within their social and cultural contexts. We can thus expand our ability to apply this theoretical lens to the development, implementation, and evaluation of intergenerational home share programs. (Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Whetung, Kruchten and Butts2020: 181)

This same topic – intergenerational home-sharing programmes – was addressed by Sánchez et al. (Reference Sánchez, García, Díaz and Duaigües2011). These authors analysed the largest programme of this type in Spain and to do so they used, among other tools, the intergenerational solidarity model. They concluded that although there were no kinship ties between the home owners and the home seekers:

intergenerational home share programs promote some valuable dimensions of intergenerational solidarity among their participants. Therefore, implementation of these programs might constitute a good example of societal response to current European policy challenges in fostering intergenerational solidarity. (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, García, Díaz and Duaigües2011: 385)

These authors demonstrate that, with regard to associational intergenerational solidarity, home-share programmes can provide elders with access to a much higher degree of intergenerational contact; and also that the participants – both young and old – can learn and engage in different forms of this contact.

Fanghanel et al. (Reference Fanghanel, Coast and Randall2012) looked at how inter- and intra-household care and support operate. Their work covered issues of intergenerational care and support involving both family and non-family members. They plotted the exchanges of care and support:

as they are affected by familial or non-familial ties, the directions of the care and how these intergenerational relationships of care are impacted by geography (proximity), affective relationships (propinquity) and assumptions about care provision between family and non-family members. (Fanghanel et al., Reference Fanghanel, Coast and Randall2012: 3)

This combined mapping of family and non-family connections allows for a better understanding of intergenerational solidarity practices in a given context.

Finally, the work of Thang (Reference Thang, Dannefer and Phillipson2010) on strengthening intergenerational relationships through reconnection between generations highlights the ‘strong idealisation of the family model’ and contributes a relevant nuance regarding intra- and extrafamilial connection. According to this researcher, while in Western countries programmes designed to foment contact between generations focus on persons without family ties, in Asia such programmes are based on the development of family intergenerationality. By pointing this out, Thang underlines that intricate relationships exist between family and non-family terrain. This author even states that ‘such forms of emergent non-family ties thus have the potential to compensate for the limitations of the family in creating the desired cross-age relationships’ (Thang, Reference Thang, Dannefer and Phillipson2010: 205). This possible compensatory function certainly warrants greater attention.

Intergenerational contact and solidarity

In its origin, the concept of age integration – and its opposite, age segregation (Uhlenberg, Reference Uhlenberg2000) – alludes to the use of chronological age as a criterion for entry, exit or participation in social processes, that is, it means age is used as a factor and barrier in the organisation of certain behaviours. Age integration and segregation are based on the prior existence of age differentiation, that is, of a sequential distinction of roles, events, transitions and inflection points over the lifecourse (Elder, Reference Elder1975). Differentiation is the forerunner of integration, which has two basic components, often related to one another: (a) the absence of structural age barriers to contact between age groups and (b) the de facto presence of interaction between such groups (Uhlenberg, Reference Uhlenberg2000). It is not common to find dichotomous examples of total age integration or segregation but rather one and the other appear to varying degrees.

Compared to other forms of segregation, e.g. that based on gender or ethnicity, it has taken longer for age segregation to receive attention, something expressly criticised in the literature about this subject (Hagestad and Uhlenberg, Reference Hagestad and Uhlenberg2006) because age segregation has at times even been considered natural, unavoidable and, therefore, not problematic (Vanderbeck, Reference Vanderbeck2007). However, demographic ageing – and the resulting higher proportion of older people present in society – has turned this situation on its head; questions such as intergenerational care-giving, intergenerational justice or intergenerational transmission of knowledge have progressively gained importance in the social and political agenda (Kaplan and Sánchez, Reference Kaplan, Sánchez, Harper and Hamblin2014), which has helped to make both age integration and age segregation more visible (Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Russell, Vauclair and Swift2011).

Age segregation is currently considered a significant problem in contemporary societies because it limits our understanding of the ageing process, it perpetuates stereotypes and prejudice based on chronological age, and it prevents young and elderly people from learning from each other (Sun and Schafer, Reference Sun and Schafer2019). The creation of ‘islands of activity’ (Tham et al., Reference Tham, Jones, Queensland, Kaplan, Thang, Sánchez and Hoffman2020) in which persons of other ages, appearances and cultures are not present ‘diminishes the community cohesion, conviviality and the intellectual and social capital that comes with interaction and familiarity. [These islands] … also increase competition for scarce public and natural resources affecting intergenerational equity’ (Tham et al., Reference Tham, Jones, Queensland, Kaplan, Thang, Sánchez and Hoffman2020: 229). Moreover, and this is of considerable importance in relation to this article, the degree of age integration and segregation can have significant consequences on the norms and practices of intergenerational solidarity, both inside and outside the family. ‘Appropriate initiatives aimed at increased contact and co-operation across age groups could provide important social benefits’ (Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Russell, Vauclair and Swift2011: 9).

The literature on this subject often alludes to the gradual diminishment of regular contact among children, adolescents, youth, adults and elderly people in the family structures of contemporary societies (Hagestad and Uhlenberg, Reference Hagestad and Uhlenberg2005). In fact, these scholars have sounded the alarm regarding the potential limitation of reducing to the family setting all possibilities for contact between cohorts that might help counter the effects of age segregation (Hagestad and Uhlenberg, Reference Hagestad and Uhlenberg2006). This is especially true with the family setting becoming increasingly characterised by geographic dispersion, pressure and dysfunctionality, given the multiple tasks that the family must perform. The recommendation is that the harmful effects of age segregation also be prevented and countered with actions carried out in extrafamilial contexts.

Purpose

Within this framework of connection between the forms of intergenerational contact and the practices of intergenerational solidarity, the present article seeks to offer a preliminary response, in the case of Spain, to a two-fold question. Firstly, what is the situation of intergenerational contact outside the family as compared to within the family? Secondly, what factors can explain extrafamilial intergenerational solidarity – insomuch as it exists – in relation to intrafamilial solidarity – which exists beyond any doubt.

These two questions can serve as a preliminary step in addressing the question of whether a change in the habits of intrafamilial intergenerational contact – specifically, a potential reduction of such contact – could somehow increase the relevance now granted to extrafamilial intergenerational solidarity – among persons without family ties – with respect to the more traditional intrafamilial intergenerational solidarity. Although answering this question fully is beyond the boundaries of this article, it is worth keeping it in mind because, in the end, the overall aim is to explore the problem of how the forms of intergenerational solidarity might be affected in increasingly ageing societies.

Data and method

The data used in this study come from three opinion surveys conducted by Spain's Centre for Sociological Research (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS)) in 2008, 2015 and 2018. These opinion surveys are national in scope, consist of personal interviews addressed to individuals conducted in homes and the survey universe is the Spanish population over the age of 18. The sample size of each opinion poll is around 2,500 people of both sexes chosen randomly around the country through proportional allocation. In all three cases the sampling procedure is multi-stage and stratified by conglomerates, with selection of the primary sampling units (municipalities) and the secondary units (sections) in a proportional random way, and last units (individuals) by random routes and gender and age quotas. Regarding the sampling error, for a confidence level of 95.5 per cent the margin of real error is ± 2.0 per cent for each sample set. Although it is not usual, from time to time these surveys address questions that have to do with contact and solidarity between age groups, as was the case in the three years selected. Exceptionally, only the surveys carried out in March 2015 (CIS, 2015) and March 2018 (CIS, 2018) also included a section intended to explore patterns of intergenerational living and interaction between generations, both among family members and among persons not linked by family ties. For this reason our analysis focused primarily on these two surveys.

Study 1

The analysis was divided into two parts. Using cross-tabulation tables and measures of association, the first part described the recent evolution of habits related to contact between different age groups, as a means of learning about the country's degree of age integration. The study of intergenerational contact revolved around two types of contact: intergenerational living and regular interaction. The first involves residing in the same household while the second does not.

Intergenerational living patterns were described using the data obtained from the two following questions, included, respectively, in the three selected surveys: ‘Do you live with a person over the age of 65, even if not on a continual basis?’ (CIS, 2008) and ‘Do you live with relatives over the age of 65 or with persons over the age of 65 who are not relatives?’ (CIS, 2015, 2018). As regards the form of contact called ‘regular interaction’, we looked at the responses given in the years 2015 and 2018 to two questions: ‘Do you have regular interaction with relatives under the age of 35 or over the age of 65 with whom you do not live?’ and ‘Do you have regular interaction with persons under the age of 35 or over the age of 65 who are not relatives and with whom you do not live?’

Study 2

In the second part, taking only the most recent data and using multivariate statistical analysis – factor analysis and logistic regression – a detailed study was performed of the dimensions of intergenerational solidarity inside and outside the family with the population aged 65 and older in 2018. In this study the criterion applied by Sun and Schafer (Reference Sun and Schafer2019) was used, according to which if the age difference between two persons is greater than 10 years these non-related persons can be considered to belong to different cohorts. In consequence, any sign of solidarity shown by a person aged 55 or under towards a person aged 65 or older was interpreted as an intergenerational solidarity practice and thus object of analysis.

Initially, in this second study the responses to the following two questions were used: ‘How frequently do you do each of the following activities with your relatives aged over the age of 65 with whom you do not live, although it is with only one of them?’ and ‘How frequently do you do each of the following activities with persons aged over 65 who are not relatives and with whom you do not live, although it is with only one of them?’ In both questions the activities considered in the questionnaire were a total of six: Talk on the phone, Talk in person, Go for a walk, Go shopping, to the cinema or to a show or do some other leisure activity, Help with self-care or with household tasks and Share in household tasks or the care of other elders. The analytical strategy consisted, firstly, of identifying, through confirmatory factor analysis, the possible existence of one or more of the dimensions of intergenerational solidarity proposed by Bengtson and Roberts (Reference Roberts, Richards and Bengtson1991), both intrafamilial and extrafamilial.

Then, to try to specify which independent variables might explain the intergenerational solidarity practices in either case, different logistic regressions were performed, as indicated below.

As dependent variables we used intergenerational solidarity activities with persons over the age of 65 in relation to the two dimensions identified in the factor analysis: associational and functional solidarity. To this end, we considered associational solidarity to take place when one of the following activities was practised frequently, i.e. every day or almost every day, and once or twice a week: (a) talking on the phone, (b) taking a walk or (c) going shopping, to the cinema or a show or doing some other leisure activity. In the case of functional solidarity we used the same frequency of either of the following two activities: (a) helping with self-care or household tasks or (b) sharing in household tasks or the care of other persons. The dichotomous categories of the dependent variable were: performing intergenerational solidarity activities – associational or functional – frequently as opposed to sporadically or never.

As for the independent variables, which were also considered dichotomously, the survey data used provided the following variables (the reference category is indicated in parentheses):

• Age (adult). The database included only individuals between 18 and 55 years of age, to guarantee intergenerationality with regard to persons over the age of 65. Two categories were established: youth – from 18 to 34 years of age – following the same criterion as applied in Study 1, which was imposed by the age categorisation present in the survey questionnaire; and adult – from 34 to 55 years of age.

• Gender (male).

• Distance (over 30 minutes): distance, in minutes, at which the respondent lives from the person over the age of 65 with whom he or she interacts the most. Those living between 1 and 30 minutes away, door to door, as opposed to those living 31 minutes or more away.

• Civil status (unmarried): married persons as opposed to unmarried persons, whether single, widowed, separated or divorced. Using this variable made it unnecessary to add the variable of living alone or not.

• Employment situation (not working): the situation of being employed as opposed to not being employed – retired, pensioner, student, unpaid care and domestic work, or other situations.

• Relationship with grandparents (no contact): it was also taken into account whether the respondent indicated having had a relationship with his or her grandparents, either at the present time or in the past.

Results

Study 1: Forms of contact

The first question posed focused on the situation of extrafamilial as opposed to intrafamilial intergenerational contact.

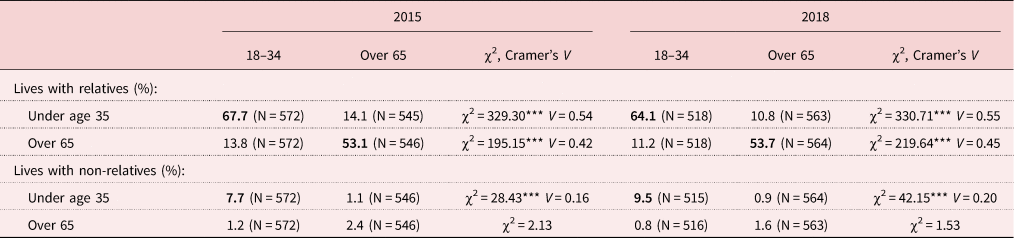

As regards intergenerational living, i.e. co-residence, a form of contact that implies living in the same household, the 2008 data indicated that at that time 62.8 per cent of the persons over the age of 65 lived with someone else of the same cohort; in contrast, only 34 per cent of the adults under the age of 35 surveyed – that is, persons between 18 and 34 years of age – lived with a person over the age of 65 – family member or not (χ2 = 97.01, p = 0.000, V = 0.28). This last percentage fell to 15 per cent seven years later (CIS, 2015) and in 2018 it was 12 per cent (CIS, 2018), as shown in Table 1. There is clearly an accumulated tendency towards less intergenerational living between these two age groups – in one decade, 55.9 per cent fewer people aged 18–34 lived with persons over the age of 65. Additionally, in 2018, such intergenerational living continues to occur overwhelmingly (92.3%) among people with family ties – in fact, intergenerational living between non-family members was practically non-existent (0.8%). As regards intergenerational living, the results indicated that the difference between intrafamilial habits and extrafamilial habits was highly relevant.

Table 1. Proportion living with relatives/non-relatives, by age group

Furthermore, as shown in Table 1, when people lived together, percentages were significantly higher when it involved members of the same age group (intragenerational living), except in the case of older people living with older people who were not relatives, which was practically non-existent. In other words, it was young people who most tended to live with young people, while older people most tended to live with older people.

More precisely, Table 2 – created using the data of Table 1 – presents, in a different way, the living patterns according to whether the person lives with others of the same age cohort. Basically, the habits remained constant in the three-year period, 2015–2018, although in the last year it was adults under the age of 35 who most clearly tended to live with non-relatives of the same cohort. The data from both surveys indicate that living with relatives clearly followed the formula of living with persons of the same cohort, of the two considered.

Table 2. Proportion living with persons of the same/different age cohort, by age group

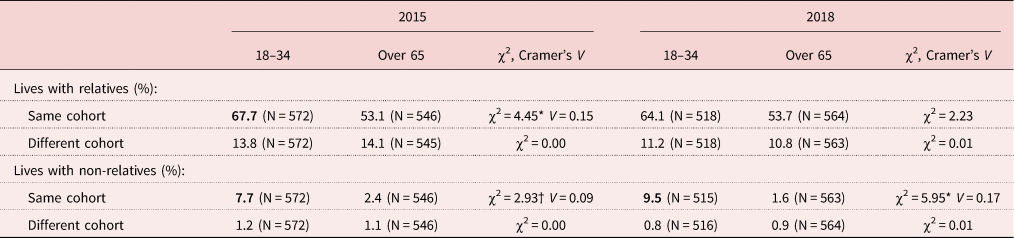

As regards contact without living together, i.e. regular contact, between persons under the age of 35 and persons over the age 65, the data analysed (CIS, 2015, 2018) indicate, as can be seen in Table 3, that while in 2018 a total of 93.4 per cent of persons between the ages of 18 and 34 said they had regular contact with relatives over the age of 65 with whom they did not live, the proportion drops to 43.8 per cent when the contact is with older persons to whom they are not related. In 2015 these percentages were 94.4 and 56.2 per cent, respectively; in three years the distance between these two forms of contact – intra- and extrafamilial – grew by 11.4 percentage points due to the reduction in contact with elderly persons not linked by family ties.

Table 3. Proportion of persons with whom the respondent does not live but does have regular contact, by age group

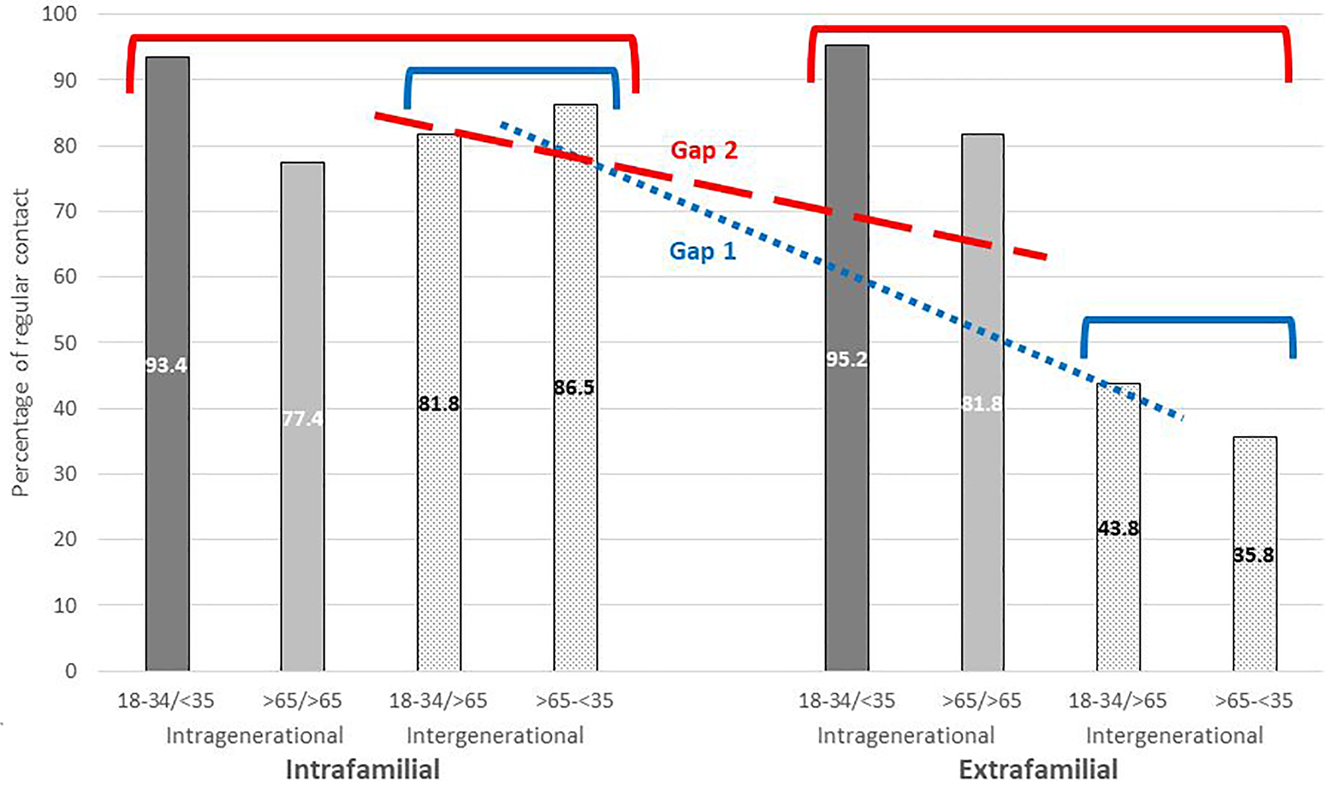

In the three-year period analysed, intergenerational contact remained high between persons over age 65 and under age 35 who were linked by family ties, especially the contact the latter reported having with the former, but intergenerational contact between non-relatives in these cohorts was comparatively very low, and also showed a downward trend. It can thus be said that as regards intergenerational contact between these age groups – that is, when there is regular interaction but they do not live together – the data pointed to what might be called a first gap (Gap 1) between family practices and non-family practices, which in 2018 was as high as 50.7 percentage points – the difference between a and b in Table 3 – in the case of contact that the elderly people reported having with persons under age 35.

Moreover, the data indicated that Spanish society seems to be segregated – with reference to the behaviour of the age groups analysed – outside the family setting. In the extrafamilial setting young people tended to have significantly more contact with other young people while older people tend to have more contact with other older people – this is what is known as intragenerational contact. Thus, in 2015 a total of 84.5 per cent of persons over the age of 65 had regular contact with a non-relative of their cohort, and three years later the percentage was similar (81.8%). The same thing was detected in the case of adults under 35 years of age: 96.3 per cent had contact in 2015 with persons under age 35 who were not relatives, and 95.2 per cent did so three years later. These high percentages contrasted sharply with those of intergenerational contact between these two cohorts, which were 56.2 and 43.8 per cent in 2015 and 2018, respectively. These data make it clear that age segregation exists between these groups when the individuals are not linked by family ties.

However, as regards in-family intragenerational contact, 77.4 per cent of persons over the age of 65 reported, in 2018, having contact with relatives of the same age group. The percentage was 83.3 per cent in 2015. In the case of young people this very non-segregationist pattern is repeated: 93.4 per cent of adults under the age of 35 had regular interaction with relatives under the age of 35 in 2018 and 94.4 per cent in 2015. These proportions are equivalent to those found for intergenerational contact within the family. Therefore, if we limit our analysis to the family setting, age segregation can be said to disappear because intra- and intergenerational contact occurs in an equivalent manner: within families, the existence of intra- and intergenerational contact is both pronounced and similar, the opposite of what happened between persons without family ties.

The results showed that outside the family not only was it true that intergenerational contact fell with respect to family contact (Gap 1) but also that intragenerational contact remained high – and was equivalent to family contact – which suggests the existence of a second gap (Gap 2). In Figure 1 the two gaps are shown for the year 2018.

Figure 1. Gaps in intra- and extrafamilial contact in 2018.

Note: In the x-axis a slash (/) is used to differentiate age groups in contact. While Gap 1 compares intergenerational contact, Gap 2 expands the comparison to include the combination of intra- and intergenerational contacts.

Source: Developed by the authors based on CIS (2018).

This first study found that, despite having fallen since 2015, in 2018 in Spain there were still 43.8 per cent of persons aged between 18 and 34 years of age that did have regular interaction with persons over the age of 65; and if this age group was broadened to include people up to the age of 55 – to guarantee the minimum distance of a decade with any person over the age of 65 – this percentage rose to 55.5 per cent. This figure prompted us to ask ourselves about the type of intergenerational solidarity that this group practised with respect to elderly people, and this question constituted the central element of the second study.

Study 2: Intergenerational solidarity, inside and outside the family

The first question to answer in this case was what type of intergenerational solidarity practices took place between people of different generations not linked by family ties, in contrast with those that took place when they were relatives. The analysis focused on practices in which the recipients of support were the persons aged over 65. The possibility of such practices was based on the finding that 84.7 per cent of persons between the ages of 18 and 55 had regular interaction with relatives over the age of 65, in contrast with the 55.5 per cent who had regular interaction with persons over the age of 65 who were not relatives.

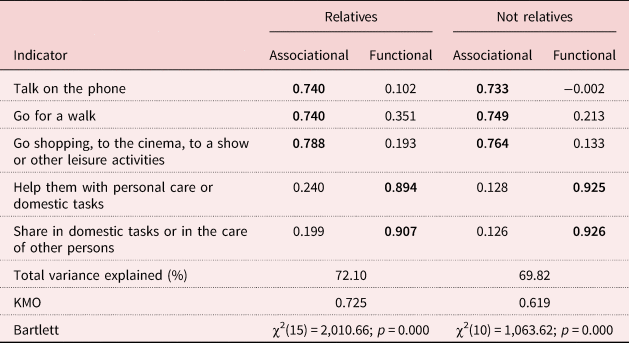

The confirmatory factor analysis, the results of which appear in Table 4, identified two factors that coincided with two dimensions of the six used by the intergenerational solidarity model: associational solidarity and functional solidarity. The survey question referring to the frequency with which various forms of activities are carried out has been used in this case. Response categories (between never and almost every day), having an ordinal character, has been treated as numerical or quantitative to make them suitable for this type of analysis. The first factor integrated activities that expressed frequency of contact (Talk on the phone, Go for a walk and Go shopping, to the cinema or to a show or other leisure activities); in the case of the second factor the activities had a more instrumental character and were related to care-giving tasks, both personal and domestic care. These two variables (Help them with personal care or domestic tasks and Share in domestic tasks or in the care of other persons) are closely related to each other, hence the high and identical correlation (above 0.9) of each variable with its corresponding factor.

Table 4. Indicators of intergenerational activities and associated loadings on the two factors identified (dimensions of intergenerational solidarity in persons aged 18–55 with persons over the age of 65), 2018

Notes: The extraction method was principal component analysis with Varimax rotation and Kaiser normalisation. Loadings of the indicators that exceed 0.4 are bold.

Source: Developed by the authors based on CIS (2018).

The results revealed that, in at least two of its dimensions (associational and functional), intergenerational solidarity occurred both inside and outside the family. Table 5 shows the frequency with which activities were performed in 2018 with elderly relatives and non-relatives, respectively, on the part of those performing the activity.

Table 5. Frequency of associational and functional intergenerational solidarity activities with elderly relatives and non-relatives (persons aged 18–55 with persons over the age of 65), 2018

Notes: The scores of each activity correspond to the average frequency reported, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (every day or almost every day). Standard deviations are in parentheses. Significant differences are bold.

Source: Developed by the authors based on CIS (2018).

The data show that in all cases intergenerational solidarity with older persons was practised with significantly more frequency when the persons had family ties, as was expected according to the literature. However, since the initial research question focused on the potential relevance of extrafamilial intergenerational solidarity, and even though the data made it clear that this type of solidarity occurred less frequently, its characteristics were carefully analysed.

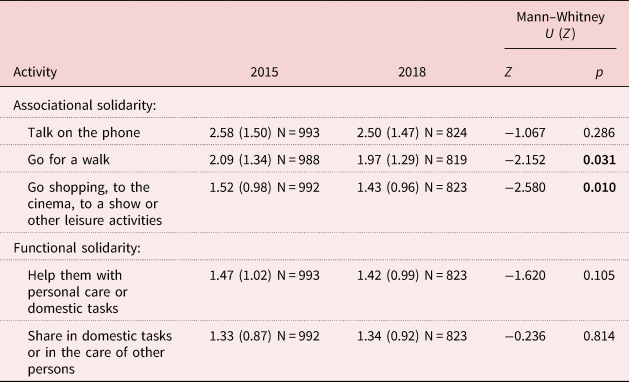

First of all, possible differences in the three-year period, 2015–2018, in relation to the practice of intergenerational solidarity with non-relatives over the age of 65 were analysed (Table 6).

Table 6. Frequency of intergenerational solidarity activities by persons aged 18–55 with non-relatives over the age of 65 with whom they do not live, evolution 2015–2018

The results indicated that the differences in the period were slight and affected only associational solidarity: only two activities – Go for a walk and Go shopping, to the cinema, to a show or other leisure activities – experienced a significant reduction in frequency. It may be the case that higher differences could not be demonstrated perhaps because three years is a period of time too small to appreciate any significant change. Future polls will be required to interpret further variations in these practices.

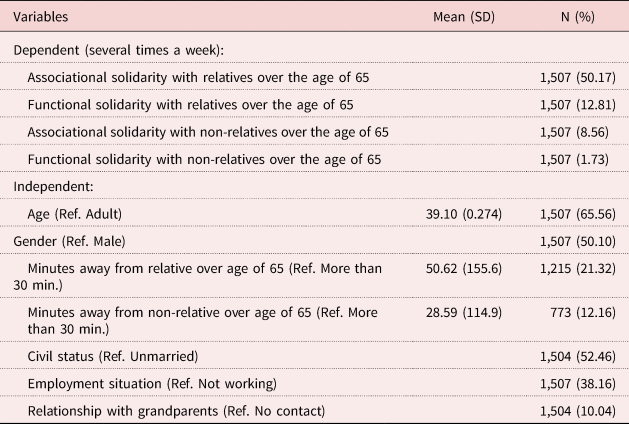

Secondly, to answer the question about possible differences between the practice of intra- and extrafamily solidarity in terms of explanatory factors, an analysis using logistic regression was performed. This analysis compared the intrafamily practices to the extrafamily practices in 2018, following the procedure explained in the Data and Method section. Table 7 presents a description of the variables included in the regressions.

Table 7. Characteristics of variables

Notes: SD: standard deviation. Ref.: reference category.

Regarding the values in each one of these variables, there is a substantial difference between frequencies of variables referring to solidarity with non-relatives over the age of 65 compared to solidarity in the family sphere with the same age group. However, since these were the only data available, it was decided to include them in the analysis as the only way to address potential contrast between familial and non-familial activities of intergenerational solidarity.

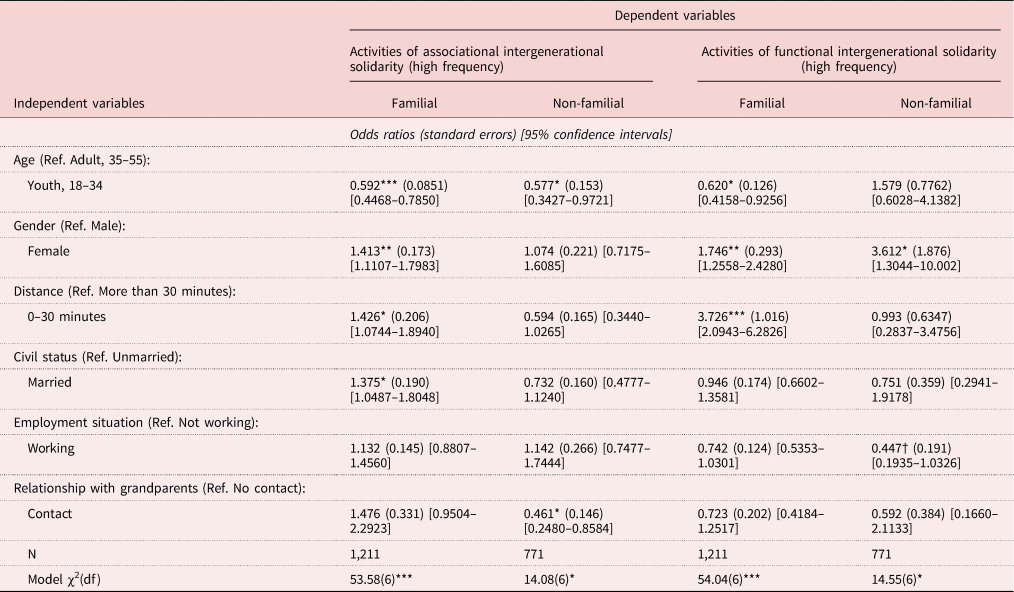

Finally, Table 8 shows the results of the logistic regressions corresponding to the explanatory model proposed by virtue of the available variables.

Table 8. Logistic regression of associative and functional intergenerational solidarity

Notes: Ref.: reference category. df: degrees of freedom.

Significance levels: † p < 0.10,* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Regarding associational intergenerational solidarity within the family, it was found that the relationship between the coefficients of the model and the probability of performing associational activities frequently with a relative over the age of 65 with whom the person does not live was statistically significant. The statistically significant variables were age, gender, civil status and the distance in minutes from the relative with whom the respondent had most contact. In the case of age, the ratio of occurrence of associational solidarity for young people (aged 18–34) compared to adults was lower (odds ratio (OR) = 0.59, p < 0.001). With regard to gender, being a woman (as opposed to being a man) increased the ratio of occurrence of these association activities taking place frequently with relatives over the age of 65 (OR = 1.41, p < 0.01). Both being married (OR = 1.37, p < 0.05) and the relative living nearby (OR = 1.43, p < 0.05) had a positive effect on the probability of providing associational support frequently.

In the case of associational intergenerational solidarity with non-relatives over the age of 65 with whom the respondent did not live, age was again significant in the same way as in the associational solidarity of young people with their elderly relatives; similarly, the ratio of occurrence of associational solidarity with an older non-relative diminished when the respondent was young (OR = 0.58, p < 0.05). Having had a relationship with one's grandparents had a negative influence when it comes to carrying out these associational intergenerational activities (OR = 0.46, p < 0.05).

With regard to functional solidarity towards relatives over the age of 65 with whom the respondent did not live, three variables turned out to be significant: age, gender and the distance of the elderly relative with whom the respondent had the most contact. In the case of age (OR = 0.62, p < 0.05), being a young adult (aged 18–34) reduced the probability of performing functional solidarity activities, as compared to adults aged 35–55. Both being a woman (OR = 1.75, p < 0.01) or living nearby (OR = 3.73, p < 0.001) – especially the latter – had a positive effect on providing instrumental support on a regular basis. The following details describe the persons who perform such functional solidarity: an adult woman who lives near the person over the age of 65 – as occurred in the case of associational solidarity with elderly relatives.

Finally, with respect to instrumental support for non-relatives over the age of 65 with whom the respondent did not live, although the model was less explanatory, gender emerged as the key element (OR = 3.61, p < 0.05); being a woman substantially increased the probability of providing instrumental support on a regular basis. Although with a greater margin of error it can also be said that having a job (OR = 0.45, p < 0.10) reduced the probability of carrying out functional activities with non-relatives over the age of 65.

Discussion

Generally speaking, it can be said that our examination of how the ageing of the population – and the increased co-existence of generations that comes with it – could be affecting patterns of upward intergenerational solidarity and contact, both co-residence and regular contact, indicates that in Spain familialism remains in full force (Ortega and Fernández, Reference Ortega and Fernández2018); basically, adults live with, have regular interaction with and practise solidarity with elderly persons with whom they have family ties. Nothing really new up to here (Bazo, Reference Bazo2012). The singular aspect of this study appears when this conclusion is nuanced with the analysis of how intra- and intergenerational contact and solidarity function between non-relatives. So far, studies on Spain have focused just on intergenerational family solidarity (Meil, Reference Meil2011; López et al., Reference López, González and Sánchez2015; Gas Aixendri, Reference Gas Aixendri, Cavallotti Oldani and Bramanti2019).

The first question posed in this research alluded to the situation, in Spain, of extrafamilial intergenerational contact in comparison with intrafamilial. In this regard, it has become patent that intergenerational living is something that takes place between relatives – between non-relatives there is a very significant reduction in this type of contact (Marí-Klose and Escapa, Reference Marí-Klose and Escapa2015). To understand intergenerational living between young adults and elderly persons, the existence of family ties continues to be a key explanatory factor, and this is so despite the decrease in this particular type of living pattern in the three-year period analysed. In this regard it is worth looking into the possible negative impact that said downward trend could be having on intergenerational solidarity, because it is well known that there are dimensions of intergenerational solidarity – e.g. the functional dimension – that can be learned and practised with more assiduity and intensity when the people involved live under the same roof (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, García, Díaz and Duaigües2011). As for intragenerational co-residence, not only does this living pattern clearly prevail over intergenerational living, it also, between 2015 and 2018, maintains its levels both inside and outside the family; and it is practised, especially, among young adults (aged 18–34) and persons under the age of 35 – with both relatives and non-relatives – and to a lesser extent among older relatives. These results lead us to wonder about the possible existence of an early context of age segregation in the co-residence patterns of the generational groups analysed. Although the results generated do not allow us to delve into that matter, when it comes to studying the question it is necessary to clarify the difference between co-residence habits and age segregation. The former are often the product of the structure of the lifecourse, e.g. the phase of emancipation of young people from the parental home lends itself to young people opting for intragenerational accommodation (Gentile, Reference Gentile2013); while the latter is something different: in the case of age segregation there are barriers that hinder or prevent intergenerational living from taking place (Ramírez and Palacios-Espinosa, Reference Ramírez, Palacios-Espinosa, Gu and Dupre2019).

With regard to intergenerational contact that does not involve co-residence, an important gap also appears (Gap 1) between intrafamilial and extrafamilial practices: again, and in line with previous research (Connidis, Reference Connidis2014), the former remain high –much higher than co-residence, as was to be expected – while the latter are not only less frequent, they are also falling. Take, for example, the fact that in Spain people over the age of 65 have less than half the contact with persons aged 18–34 who are not members of the family than they do with persons of this age group who are members of the family. It would be important to assess the consequences of Gap 1 in the case of older persons who either have no family or whose family is not within contact range – in Spain, around two million people over the age of 64 live alone (INE, 2019b) and, in 2016, 15.2 per cent of persons aged 65 and over met with their closest relative just once a month or less frequently (CIS, 2016). In addition, steps must be taken to halt the progressive reduction in regular intergenerational contact if we do not want the family to necessarily be the only pillar of support for older people in need of intergenerational solidarity, a risk already mentioned above (Hagestad and Uhlenberg, Reference Hagestad and Uhlenberg2006). For this reason, studies on intergenerational solidarity with elderly people, in addition to examining family practices, should also study the practice among people who are not relatives, as the second part of this project did.

What happens in the case of intragenerational contact? Something quite striking: its levels inside and outside the family are comparable, which does not happen with co-residence. This is why it has been necessary to point out Gap 2: it is not only that intergenerational contact falls sharply outside the family setting but also that intragenerational contact maintains its levels. In consequence, when seen as a whole, intrafamilial contact – aside from co-residence – does not seem to show age segregation but extrafamilial contact does. Here arises a second context of possible segregation – now with respect to contact between persons who do not live together – which warrants further examination for many reasons, one being that intergenerational integration is a critical factor in shaping the experience of older adults living alone (Portacolone, 2015).

The second research question posed alluded to the factors that might explain extrafamilial intergenerational solidarity – to the extent that it exists – in comparison with intrafamilial intergenerational solidarity – the existence of which has been well demonstrated in the literature (Cavallotti and Marcaletti, Reference Cavallotti and Marcaletti2017; Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, López and González2019). In effect, the analyses have shown that both the associational dimension and the functional dimension of intergenerational solidarity also arise outside the family system, although within the family is where it happens most. Therefore, the family might serve as the first ‘intergenerational solidarity school’ by promoting learning experiences that later become the foundations for practising the same solidarity among persons without family ties, as has been found in the case of intergenerational home sharing (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, García, Díaz and Duaigües2011). This type of reasoning suggests that intra- and extrafamilial intergenerational solidarity might be connected, like a system of communicating vessels. This possibility needs to be investigated further. In fact, previous research has encouraged – as results from this paper do –exploring ways of bridging the divide between familial and non-familial intergenerational solidarity (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, Sáez, Pinazo, Cruz-Saco and Zelenev2010) but progress in this regard has been scarce.

Among the explanatory factors of associational and functional intergenerational solidarity with persons over the age of 65, both intra- and extrafamilial, it turns out that gender and age play a central role. Women stand out significantly in activities of associational solidarity in the family and are more likely to perform functional intergenerational solidarity in both settings. The well-known role of women in intergenerational care-giving activities (Roca, Reference Roca2014; Haberkern et al., Reference Haberkern, Schmid and Szydlik2015) appears yet again, but this time beyond family lines. This last detail is of great interest because it indicates that women can be the connecting element between intrafamily and extrafamily functional solidarity – in a context in which family care-giving is increasingly seen as a responsibility to be shared by men and women (Meil, Reference Meil2011). This should be taken into account when formulating intergenerational solidarity programmes and policies aimed at ‘bridging intergenerational capital’, i.e. the sharing and exchange of intergenerational knowledge and know-how between familial and non-familial settings (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, Sáez, Díaz and Campillo2018).

Another one of the fundamental explanatory variables is age. It is the not-so-young adults – in our research, those aged between 35 and 55 years – who play the main role in associational solidarity both inside and outside the family and also in functional solidarity outside the family. Bearing in mind that the 18–34 age group is the one that practises the most intragenerational co-residence, with both relatives and non-relatives, and is also the group that has the most contact with people under the age of 35, both in and out of the family, we may be looking at a cohort effect. This is something that should be followed closely, to see whether the solidarity shown currently by older adults lessens when today's younger adults occupy that same age range.

The distance to the place of residence of the elderly person with whom the respondent has most contact only explains associational and functional intergenerational solidarity within the family, not outside it. Living nearby – less than half an hour from door to door – increases the likelihood of carrying out associational solidarity but, above all, functional solidarity. The question of why distance is not significant when explaining these dimensions of solidarity outside the family should also be the topic of further research.

Likewise, civil status – specifically, being married – is relevant only in the case of familial associational solidarity. Among non-relatives, associational solidarity seems to be marked by having had less contact with one's grandparents while functional solidarity is more marked by the fact of not working. It may be that the type and frequency of contact – that is, associational solidarity – with non-relatives over the age of 65 is influenced by the fact of not having had this type of relationship with one's own grandparents; and that having more time available – due to not working – is one of the keys for understanding why functional solidarity with elderly people outside the family is practised frequently. In this regard, it is possible that expressive motives and voluntarity carry more weight than normativity – the belief in a commitment that prompts one to stay in contact with and take care of older people in the community – when it comes to explaining facets of intergenerational solidarity outside the family.

Limitations

Although the opinion surveys used, which have a long and highly respected tradition in Spain, included the new feature of contrasting the intra- and extrafamilial vision of contact and solidarity, it would have been better to have more independent variables available, as they would have allowed for a more detailed study of intergenerational solidarity among non-relatives. Despite this limitation, we opted to make the most of the fact that for the first time the Centre for Sociological Research addressed in its studies questions about co-residence, contact, and activities with relatives and non-relatives. Although in 2018 some of the questions asked three years earlier were replicated, which provided data from two different years, more time is required – not just a three-year period – to be able to reach solid conclusions about trends concerning both perceptions and behaviours of the Spanish population in this subject area. In consequence, the results of the present research can be considered only preliminary.

Many of the elements characterising this research were shaped by the configuration of the surveys, as occurs with studies that make use of secondary data. One such element that has limited the results is the delimitation of the different age groups – e.g. using the age interval of 18–34 as the age group whose habits of co-residence, contact and solidarity with persons over the age of 65 were analysed; or having to consider the relationship between persons of this group and ‘persons under the age of 35’ as intragenerational – because it was pre-established in the questionnaires. Future studies should be able to work with more flexible age groupings that are capable of responding more appropriately to the diverse generational configurations arising during the different stages of the lifecourse.

The data referring to contact with non-relatives, especially with persons over the age of 65, were obtained from a limited number of individuals in the samples. While it is true that intergenerational relationships within the family are more frequent, with a larger sample of extrafamilial cases it would have been possible to go much further in our effort to clarify the diversity of key explanatory factors that would most help us to understand the similarities and differences among the intergenerational solidarity practices considered in an inclusive manner, that is, including both familial and non-familial settings.

Implications

The analyses performed have demonstrated that there is reason to pay combined attention to both extrafamilial and intrafamilial forms of contact and intergenerational solidarity, something that has been done very little to date. In consequence, the fields of family studies and intergenerational studies – dedicated mainly to the analysis of extrafamilial intergenerational programmes and policies – should bring their research agendas nearer to each other and consider possible means of collaboration, something that has been proposed by some authors (Hans and Ponzetti, Reference Hans and Ponzetti2004).

In addition, generational policies, in both their descriptive and their programmatic versions (Lüscher and Klimczuk, Reference Lüscher and Klimczuk2017), should contemplate both the private sphere (family) and the public sphere (organisations, community, macro-social elements) in their aim to institutionalise channels by which to establish individual and collective relations between the generations. It is worth reconsidering the strategy according to which, for example, grandparent–grandchild relationships and the relationships between students at a school and a group of elderly mentors that collaborate in their education should always be separate objects of political attention. It may be that the connection between one form of intergenerational contact and solidarity and the other is in fact closer than previously thought.

Conclusion

The gist of this paper has to do with potential patterns of connections between intergenerational contact and solidarity inside and outside the family in Spain. Approaching the study of this issue through a parallel analysis of familial and non-familial practices not only broadens the scope of this area of inquiry, but allows for formulating new research questions linking family and intergenerational studies. In the case of a country like Spain, it has proven to be illuminating this combined analysis of intrafamilial and extrafamilial intra- and intergenerational contact (intergenerational living and regular interaction) between age groups to the point of identifying the existence of a couple of unnoticed gaps with potential impact in terms of age segregation and intergenerational solidarity throughout the lifecourse that need further investigation. Moreover, if the possibility of recreating intergenerational solidarity outside the family is a realistic option (Labit and Dubost, Reference Labit and Dubost2016), twin studies of different and coinciding independent variables behind familial and non-familial dimensions of that solidarity would need to be developed in the future, as this paper has carried out tentatively.

Financial support

Translation into English of the original Spanish manuscript of this paper was funded by the Department of Sociology (University of Granada).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study did not need require approval by the Ethics Committee in Human Research (University of Granada) for only secondary data analysis has been carried out.