Introduction

East Asian countries are ageing rapidly, rendering economic security all the more important for the greying population. Whilst elderly people in these societies have traditionally relied on their families for care, average family size has shrunk significantly in recent decades, thus weakening the capacity of ‘familialism’ and raising the need for state intervention.Footnote 1 Pension reforms are a key political priority across the region, with a focus on increasing pension coverage and benefits to provide basic income security for all citizens. However, this movement to expand existing pensions conflicts with budget austerity following the structural transformation of labour markets in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis (Bonoli and Shinkawa, Reference Bonoli, Shinkawa, Bonoli and Shinkawa2005; Zhou and Shi, Reference Zhou, Shi, McBride and Evans2017). Policy dynamics go hand in hand with heated debates within academia and amongst practitioners over the sustainability of the existing pension systems to provide adequate old-age security. In the middle stands the governance challenge to establish an appropriate balance between public and private pensions (Ebbinghaus and Gronwald, Reference Ebbinghaus, Gronwald and Ebbinghaus2011), for which East Asian experiences share common concern and provide crucial relevance.

East Asian pension systems have attracted considerable research interest in terms of residualism or developmentalism.Footnote 2 Whilst these labels reflect certain features of pension policy, these approaches are prone to borrowing too many theoretical concepts without solid empirical evidence (Holliday, Reference Holliday2005; Kwon, Reference Kwon and Kwon2005; Kim, Reference Kim2008). Quite a few pension policy studies have provided valuable information about the political processes and policy outcomes of various countries (Kim and Kim, Reference Kim, Kim, Bonoli and Shinkawa2005; Lin, Reference Lin, Bonoli and Shinkawa2005; Shinkawa, Reference Shinkawa, Bonoli and Shinkawa2005a; Joo, Reference Joo2010; Shi, Reference Shi, Mok and Ku2010). However, such studies tend to overlook the overall trends in pension reforms in the region. Most studies also account for the private element of old-age security in the narrow sense of family support, whilst neglecting other, equally important players such as occupational pensions (Vangunsteren and Rein, Reference Vangunsteren and Rein1985; Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Powell and Barrientos, Reference Powell and Barrientos2004). A surprising gap exists between the holistic approach that specifies pension policy with an ‘East Asian’ brand and the atomistic explanation that focuses merely on the pension policy of particular countries. Equally missing in the current pension research is the reflection on the significance of East Asian pension reforms for the prevalent concern for ageing and old-age security.

Against this background, this article suggests a straightforward but more fruitful way to categorise the major approaches to pension policy in East Asia through comparing institutional characteristics with quantitative indicators. This comparative institutional analysis promises to chart the ‘pension landscape’ in East Asia, depicting the current state of public–private pension mixes and institutional structures. The analytical goal of the present study is less ambitious than the prevalent practice that bundles heterogeneous countries as a single ‘East Asian welfare regime’ with little regard to the subtle institutional variations of the respective welfare systems. Placing pension policy in a broader comparative perspective helps present a clearer picture of how East Asian countries have been responding to the issues related to ageing populations. Institutional variety in this regard also implies certain strengths and weaknesses associated with each specific pattern of public–private pension mix – with profound implications for old-age security.

The next section critically reviews existing studies of East Asian welfare regimes, placing them in a broad frame of reference to the current pension debates, in an attempt to analyse the variety of pension institutions and policy outcomes. The third section identifies three types of pension systems and compares their institutional structures in terms of the composition of public–private provisions. The fourth section presents key indicators demonstrating the outcomes resulting from diverse institutional features; and the final section summarises the findings and reflects on their theoretical significance and policy implications.

Comparative institutional analysis of pension policy: debates and insights

The 1990s saw growing academic interest in East Asian welfare states. Inspired by Esping-Anderson's (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) welfare regime approach, scholars sought to identify a welfare model specific to East Asia. For example, the cultural perspective focuses on the impact of Confucianism and explores the familialism inherent in such social policies (Jones, Reference Jones1990, Reference Jones and Jones1993; Rieger and Leibfried, Reference Rieger and Leibfried2003). The productivist (or developmentalist) account explains why East Asian welfare states prioritise economic growth over social redistribution in an attempt to catch up with the advanced industrialised countries (Holliday, Reference Holliday2000, Reference Holliday2005; Holliday and Wilding, Reference Holliday, Wilding, Holliday and Wilding2003; Kwon, Reference Kwon and Kwon2005; Lee and Ku, Reference Lee and Ku2007). Both explanations put private responsibility ahead of public support in welfare provision. Whilst highlighting important aspects of the various East Asian welfare states, these accounts tend to over-simplify the variety of their features without much empirical endorsement. As Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1997) points out, East Asian welfare states are still engaged in the process of institutional building and consolidation, which may take some time to complete. For a region characterised by constant institutional transformations, previous attempts to identify a unique East Asian model have failed to produce fruitful insights. The preoccupation with the ‘welfare modelling business’ (Abrahamson, Reference Abrahamson1999) or ‘familes of nations’ (Castles, Reference Castles1993), further obscures the observation of institutional features and policy dynamics of specific social security domains such as pensions.

Fortunately, this shortcoming has attracted attention in recent pension policy research that turned to the configurations of public–private pension mixes and the policy choices embedded in specific welfare regimes (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Rein and Turner, Reference Rein, Turner, Rein and Schmähl2004; Ebbinghaus and Gronwald, Reference Ebbinghaus, Gronwald and Ebbinghaus2011; Ebbinghaus and Wiß, Reference Ebbinghaus, Wiß and Ebbinghaus2011). Leading international organisations also heeded the contextual diversity (Asian Development Bank, 2012; OECD, 2013). One exemplary report by the World Bank (2016) gives an extensive analysis of the ageing problems and the associated policy issues including retirement income in East Asia. Whilst its previous report (World Bank, 1994) controversially overweighed private pensions against their public counterparts for the sake of risk diversification, the World Bank has gradually shifted to a stance in favour of a multi-pillar model characterised by joint public–private collaboration in old-age security (World Bank, 2008; cf. Zhou and Shi, Reference Zhou, Shi, McBride and Evans2017). This course change reflects the realisation that the replacement of state pensions by private ones alone is no panacea for the ageing problem, as evidenced by the latter's vulnerability to financial market risks and the tendency to exacerbate inequality of old-age security. Even the Chilean policy conversion from a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) pension system to a fully funded alternative in 1981 – once acclaimed as a model for pension privatisation – required large-scale reform in 2008 due to high administrative costs, the exclusion of large population segments and other unforeseen drawbacks (for an overview of pension privatisation, see Orenstein, Reference Orenstein2008, Reference Orenstein2013). These ambivalent outcomes advise caution against the alleged merits of liberalisation and individual choice associated with the privatisation arguments.

Moreover, Western pension reforms have shown that countries with earnings-related PAYG public pension schemes tend to circumscribe the accretion of private provision in pensions, whereas those with a multi-pillar system (in which universal flat-rate public pension schemes provide minimum economic security) assign private pensions a principal role but simultaneously prescribe state regulation in their programmatic implementation (Ebbinghaus and Gronwald, Reference Ebbinghaus, Gronwald and Ebbinghaus2011; Leisering, Reference Leisering2011). Incremental change of the various pension systems takes place on the premise that public responsibility for pension provision and regulation remains pivotal for retirement income maintenance. These reform endeavours further indicate that no universal one-size-fits-all paragon exists for pension reform, and each country must determine a suitable re-arrangement of public–private pension composition to generate synergy effects, conditioned by its existing institutional frameworks and the characteristics of accessible labour and capital markets.

The preceding discussion points to the necessity of identifying the institutional structures of distinct pension systems and their relative strengths and weaknesses for East Asian countries. A focal shift to a comparative policy analysis can untangle the historical developments of the respective pension systems and assess their impact on old-age security outcomes. This is something the current studies of East Asian welfare have yet to address, whilst research by international organisations can equally benefit from the present study's highlighting of the institutional structures and historical origins of East Asian pension policies. The analytical strength of the proposed approach lies in reflecting the close interplay of public–private pensions by drawing a distinction between different providers (pillars) of various pension tiers (cf. Immergut and Andersen, Reference Immergut, Andersen, Immergut, Andersen and Schulze2006; Jochem, Reference Jochem, Clasen and Siegel2007).Footnote 3 This is an important consideration given the long history of pension policy in countries such as Japan and Korea, which incorporated occupational pensions on top of the public ones at the outset of welfare state development (Yi, Reference Yi2007; Estévez-Abe, Reference Estévez-Abe2008). Hong Kong and Singapore trod a different path and set up provident funds under the government's supervision. These instances suggest that the boundary between public and private pensions is never clear-cut as the proper operation of private pension schemes often requires state regulation (Ebbinghaus and Wiß, Reference Ebbinghaus, Wiß and Ebbinghaus2011; Leisering, Reference Leisering2011; Whiteside and Ebbinghaus, Reference Whiteside and Ebbinghaus2012). As such, the pillar–tier demarcation offers heuristic potential to portray a broader picture of pension policy development without losing sight of nuanced public–private enmeshment.

This appeal becomes clear when considering that some East Asian pension systems with earnings-related social insurance schemes tend to distance themselves from occupational and private pension schemes, whilst others adopt the opposite or hybrid paths (Bonoli and Shinkawa, Reference Bonoli, Shinkawa, Bonoli and Shinkawa2005; Choi, Reference Choi2008). As such, variety in the gestalt of the mixtures traces back to a long history of collective endeavours to initiate private pensions along with public pensions through the development of East Asian welfare states. Diverse approaches depart from various institutional frameworks of public–private pension mixes to address the challenge of economic insecurity in retirement due to population ageing. The scope and extent of public–private mixes in pensions reveal much about the ways in which old-age security is safeguarded by pertinent institutional regulations. It thus follows that a comparative institutional analysis can shed light on the cross-national variation amongst East Asian pension systems regarding the public–private division of labour for old-age security. One such undertaking includes a comparison of the pension institutional structures as well as the measurement of their policy outcomes by key policy indicators.

The following two sections present historical and indicator analyses, taking into account the historical paths to different configurations of public and private pension provisions. This is then supplemented with a comparison of key indicators covering three major aspects – pension adequacy, financial sustainability and the significance of private pensions – to outline the discrete policy outcomes of the respective pension patterns and their impacts on the old-age security.

Three worlds of pension system development in East Asia

East Asian pension systems have undergone significant reforms over the past few decades, but each country exhibits a certain continuity of institutional logic. Japan and Korea feature a fully fledged tier of occupational pensions which primarily favour employees of large conglomerates (keiretsu in Japan and chaebol in Korea), together with another strong tier of public pensions in the form of social insurance that covers the whole population. Meanwhile, China and Taiwan both offer pension systems composed of a hefty public pension tier, with substantial stratification in benefit levels amongst various occupation groups. Although occupational pensions are on the rise in both cases, the overall development of this segment is insufficient to ensure old-age security. Finally, Hong Kong and Singapore stand out as a prototype for pension systems operating solely with fully funded individual accounts (provident funds), jointly financed by employers and workers. Out of their residualist ideology with a distinct antipathy for public financing of social provisions, both governments have refrained from introducing any public pensions, with means-tested assistance only available to the elderly poor.Footnote 4

Institutional structures of three pension patterns in East Asia

Dualist pension systems share the burden between public and corporate pensions. In Japan, earnings-related pension schemes were introduced for public servants and military servicemen in the late 19th century, and these schemes were later merged as the Mutual Pension Schemes (MPSs) (Shinkawa, Reference Shinkawa2005b; Yano, Reference Yano2012). The Workers’ Pension scheme emerged in 1942 and extended its coverage to become the Employees’ Pension Insurance (EPI) scheme. In 1960, the government introduced National Pension Insurance (NPI) to cover the remaining population still not included under the MPSs or EPI. These legislative efforts produced a structure of different social insurance pension schemes fragmented along occupational divisions. The first attempt at integration came with the introduction of a universal Basic Pension scheme in the 1980s, merging the financial reserves of the NPI with those of other schemes (Shinkawa, Reference Shinkawa2005b; Yano, Reference Yano2012). Today, this universal scheme constitutes the cornerstone of Japan's public pensions, supplemented by the three contributory pension schemes (NPI, EPI and MPSs).

However, these broad-coverage public schemes provide low benefit levels, leaving room for corporate pensions to top up retirement income. Early schemes dating from the late 19th century received official recognition in 1935 as the Retirement Allowance (Yamazaki, Reference Yamazaki1988; Shinkawa and Pempel, Reference Shinkawa, Pempel and Shalev1996; Nishinarita, Reference Nishinarita2009; Krämer, Reference Krämer2013). After the Second World War, corporate pensions gained further momentum, along with the development of the public pension system. In addition to the Retirement Allowance, two defined-benefit (DB) corporate pension schemes, namely the Tax-Qualified Pension Schemes (TQPSs) and Employees’ Pension Funds (EPFs), came into operation (Nishinarita, Reference Nishinarita2009). However, ongoing economic liberalisation and subsequent financial difficulties forced a structural overhaul of these DB corporate pension systems with the introduction of two new corporate pension laws in 2001: the Defined-Benefit Law (the DB law) and the Defined-Contribution Law (the DC law) (Nishinarita, Reference Nishinarita2009; Yeh and Shi, Reference Yeh, Shi, Mok and Lau2014). The DB law stipulated two new types of pension plans: contract type and fund type.Footnote 5 The former aimed to replace the TQPSs, and was targeted at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with no minimum number of members required, whilst the latter replaced the EPFs with an application requirement imposed on companies with at least 300 employees. Meanwhile, the DC law, the Japanese equivalent of US-style 401k plans, attempted to reduce labour costs and shift financial risks to individuals by introducing individual-type and corporate-type pension plans. The former was designed for those under 60 years of age insured under category No. 1 (self-employed) and under the EPI, i.e. those without other corporate pension plans. The latter targeted those insured under category No. 2, i.e. those covered by the EPI with employer-paid contributions.

Korean public pensions initially covered only government employees, military personnel and public school teachers. In contrast, private-sector employees only had access to the Retirement Allowance (i.e. severance pay) under the 1954 Labour Standards Act (Yi, Reference Yi2007; Phang, Reference Phang, Yang and Klassen2010). Political democratisation in the 1980s led to the legislation of the National Pension Insurance Act to cover more private-sector employees, and this was extended later to cover the self-employed and peasants (Hwang, Reference Hwang2006). However, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis forced the government to reduce NPI benefit levels drastically, from 70 per cent in 1988 to 40 per cent in 2007. To stave off the immediate impacts of labour market deregulation and old-age poverty, the government established a nearly universal non-contributory pension in 2007, the Basic Old-age Pension scheme, providing flat-rate benefits to 70 per cent of elderly people (equivalent to 10% of average incomes under the NPI) (Shin and Do, Reference Shin and Do2014).

Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the Korean government revamped corporate pensions. Whilst the Retirement Allowance initially acted as a form of severance pay for unemployment compensation and retirement income, this function declined after the introduction of unemployment insurance and the NPI scheme (Phang, Reference Phang, Yang and Klassen2010). Furthermore, as workers laid off from bankrupt enterprises had little recourse to recover severance, the government passed the Employees’ Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in 2005 to restructure the corporate pension system. Three new corporate pension schemes are now available: a DB scheme, a DC scheme and Individual Retirement Accounts (for firms with fewer than ten employees).

By contrast, a statist pension system is characterised by the dominance of public earnings-related pension schemes with high replacement rates, rendering private corporate pensions rather dispensable. The centrepiece of Taiwan's pension system is a good example, consisting of several occupationally fragmented contributory pension schemes including the Military Servicemen's Insurance Scheme established in 1953, along with the Government Employee Insurance for Civil Servants and the Labour Insurance for Workers introduced in 1958. This fragmented pension structure remained largely intact even after democratisation in the late 1980s. Democratic competition between major political parties led to the introduction of various non-contributory pension schemes for different population groups including elderly farmers and middle- and low-income elderly people, followed by the NPI scheme that came into force in 2008 to cover those excluded from the existing programmes (Yeh, Reference Yeh2014). Taiwan currently features five pension schemes for different occupational groups, including four contributory pension schemes, and one non-contributory pension scheme for peasants aged 65 and older.

Given the predominance of public pensions, non-state pensions have never played a significant role in Taiwan. Although corporate pensions appeared in the 1950s, their operation depended crucially on the enterprises’ voluntary participation. The introduction of the Labour Standards Act (1984) turned existing corporate pension schemes into mandatory DB plans with lump-sum payments, which became known as the Labour Retirement Allowance. However, fewer than 5 per cent of retired workers qualified for such corporate pension benefits due to stringent entitlement rules (Yeh, Reference Yeh2016). To address this problem, the Labour Pension Act was introduced to replace the DB Labour Retirement Allowance with DC Individual Retirement Accounts in 2004. Even so, corporate pensions remain a bench player in Taiwan.

Meanwhile, the Chinese pension system consists of three major schemes designed for different occupational (or population) groups. The Urban/Rural Resident Basic Pension Insurance constitutes the basic pillar, covering nearly 513 million people by the end of 2017.Footnote 6 In essence, this new scheme incorporates the existing two programmes covering urban and rural residents. It is a fully funded form of social insurance, supplemented by basic pension guarantees from the central government and various supplemental benefits from local governments. Pension eligibility is conditional on 15 years of contributions. The second major scheme, urban worker pension insurance, has been operating since the socialist era but has undergone fundamental overhaul in the last two decades. In its current form, this scheme covered 379 million employees in 2016, approximately 48.8 per cent of the total national workforce (Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, 2016). The institutional structure features two tiers: the PAYG social pooling requires a contribution rate of 20 per cent of the employees’ gross wages, and the fully funded individual account charges an additional 8 per cent, with contributions shared equally by employers and employees. In addition, in 2004 the government launched pilot schemes for voluntary enterprise and individual pension savings arrangements. Enterprise Annuities are voluntary occupational plans with fully funded defined contribution accounts. Employers can contribute up to 4 per cent of payroll, whilst the combined company and employee contribution are limited to one-sixth of employees’ total salary expenses for the previous year. They are established as a trust that can take the form of either an internal or external trustee model. Enterprise Annuity schemes have primarily been adopted by large, profitable, mostly state-owned enterprises, with total assets amounting to RMB 769 billion in 2015.Footnote 7

Finally, the individualist pension system subscribes a loose regulatory role to the state that sets a statutory framework by which individuals accumulate retirement income in financial markets. Rather than state-managed and earnings-related contributory pension schemes, Hong Kong or Singapore rely on centrally or commercially managed provident funds. In 1955, Singapore launched the Central Provident Fund (CPF), the centrepiece of the social security system. Its introduction was partly due to the reluctance of the colonial government to establish a programme that would incur huge public expenditures, and partly due to its appeal to facilitate capital accumulation (Ramesh, Reference Ramesh and Kwon2005). The CPF is a DC scheme, and enrolment is mandatory for all employed Singaporeans. The CPF covers compulsory retirement savings along with medical care and housing, and has not significantly changed since its inception. In 2016, the CPF contribution rate was set at 37 per cent of total wages (17% for employers, and 20% for employees).

The cornerstone of the Hong Kong pension system is a non-contributory scheme which began operation in 1973 with very limited benefit levels (Chan, Reference Chan2011). Later developments saw the enactment of the Occupational Retirement Scheme Ordinance for private workers and pension schemes for civil servants, although both covered barely one-third of the total workforce (Chou, Reference Chou, Fu and Hughs2009). In the 1990s, a pension debate emerged with reference to the soaring social expenditures due to population ageing. Different plans were considered, even including the introduction of a contributory pension scheme. However, this policy discussion coincided with Hong Kong's return to the People's Republic of China, and the Beijing government was focused on the sovereignty transfer and showed little interest in assuming direct responsibility for social security (Ramesh, Reference Ramesh2004; Chan, Reference Chan2011; Tang, Reference Tang, Midgley and Piachaud2011). A consequent compromise led to the introduction of the Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) in 2000, a compulsory individual saving account with the contribution rate set at 10 per cent of wages borne equally by employees and employers (Yu, Reference Yu2007). Workers with monthly wages below HK $7,100 (approximately US $910) are exempted, as their full contribution is borne by their employers. In contrast to the Singaporean CPF, the MPF is a privately managed scheme operated by the trustees and other service providers.

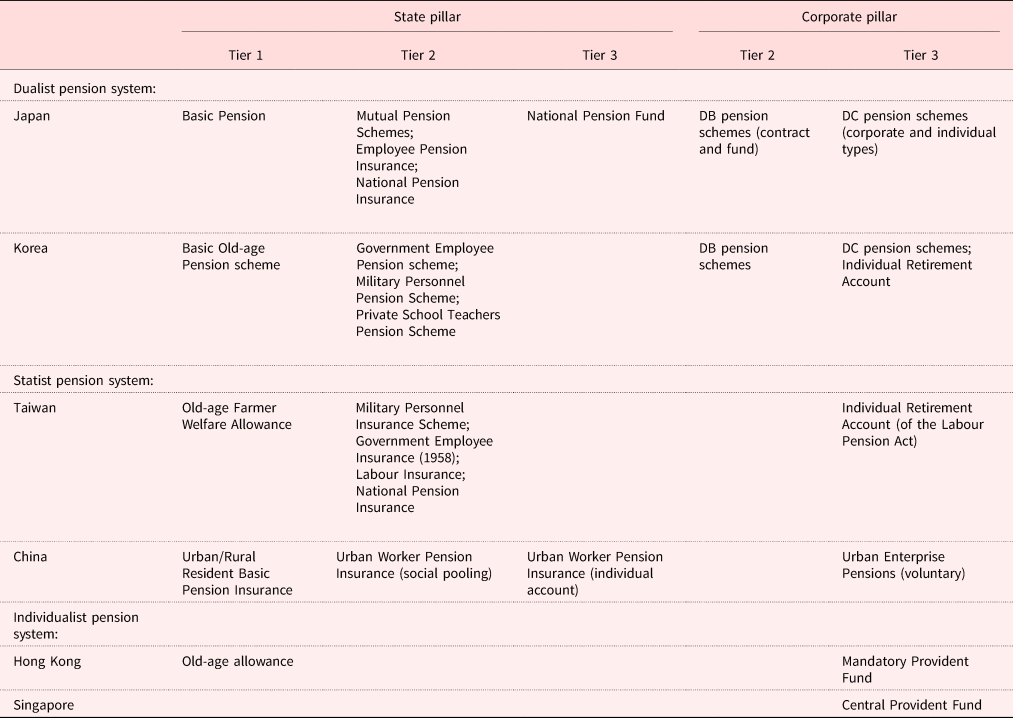

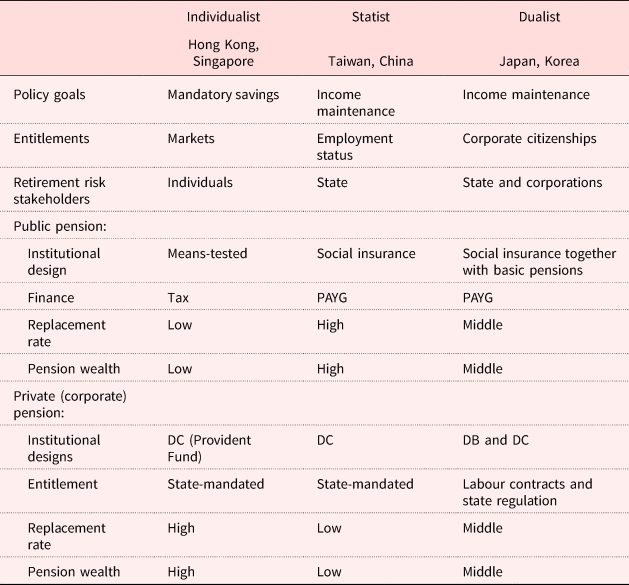

Table 1 summarises the institutional arrangements of public–private pension mixes in the six East Asian welfare states considered. The three patterns of pension composition show staunch institutional resilience to date, despite challenges posed by population ageing and financial shortfalls. Although each case has initiated several reform measures in response, none has yet essentially altered the institutional logic underlying the public–private partnerships for old-age security. China and Taiwan have launched several rounds of reforms tinkering with public pensions but have never seriously considered private provisions as an alternative. Japan and Korea followed suit, but remained highly reliant on the back-up of occupational pensions. Finally, the public in Hong Kong (and Singapore to a lesser extent) are increasingly concerned about insufficient protection for their old age, but face obstinate government resistance to any radical overhaul. Adherence to the respective principles of this public–private mix implies that certain enduring institutional forces impact the scope and extent of each pension pattern.

Table 1. Institutional structures of East Asian pension systems

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Various outcomes of public–private pension mixes in East Asia

Given the institutionalisation of specific pension mixes in the three patterns identified in East Asia, the following analysis aims to compare their policy outcomes through pension policy indicators. Social indicators initially aim to measure and monitor the level and degree of social progress and social wellbeing across time and space, but later find wide application for ‘evaluating a country's level of social development and for assessing the impact of policy’ (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Cantillon, Marlier and Nolan2002). By developing concept-driven indicators, policy analysts can inspect policy changes and measure individual and societal wellbeing (Noll, Reference Noll and Genov2004). Here we take several pension indicators to foreground the features of macro-level pension developments, and assess their impacts on old-age security. This helps explain the institutional strengths and weaknesses of various public–private pension mixes in East Asia.

Our indicator choice relates to three major aspects.Footnote 8 Since pension reforms aim to provide adequate income retirement without jeopardising their own institutional stability, two criteria matter for the evaluation: pension adequacy and financial sustainability (Chybalski and Marcinkiewicz, Reference Chybalski and Marcinkiewicz2016; Been et al., Reference Been, Caminada, Goudswaard and van Vliet2017). The most essential indicator for this purpose is the pension replacement rate that reflects the income allocation over the lifecycle (European Commission, 2015; OECD, 2015; Chybalski and Marcinkiewicz, Reference Chybalski and Marcinkiewicz2016). In this vein, another indicator, the old-age poverty rate, illustrates to what extent the pensions protect elderly people against destitution (European Commission, 2015; Chybalski and Marcinkiewicz, Reference Chybalski and Marcinkiewicz2016). Whilst these two indicators focus on the benefit generosity of a pension system, other indicators related to a system's financial sustainability are equally important: contribution rates and (net) pension wealth, which can duly demonstrate the balance between pension revenues and liabilities (OECD, 2013, 2015). Furthermore, an institutional analysis of public–private pension mixes must take private pensions into account. Where private pensions prevail, they assume an important role in supporting old-age security that the state may be reluctant (or unable) to fill. If we are to understand private roles in old-age security, the inclusion of two indicators, coverage and the size of private pension assets, will pinpoint the position of private pensions and their significance in the various pension systems (Queisser et al., Reference Queisser, Whitehouse and Whitefold2007; World Bank, 2016).

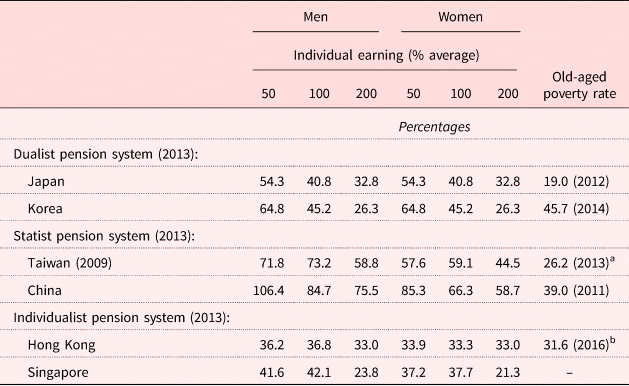

Table 2 begins the evaluation of pension adequacy by comparing the net replacement ratesFootnote 9 of mandated pension schemes in six East Asian cases, defined as the ‘individual net pension entitlement divided by net preretirement earnings, taking account of personal income taxes and social security contributions paid by workers and pensioners’ (OECD 2013, 2015). In the individualist pension system, Hong Kong and Singapore feature mandated provident funds offering 36.8 and 42.1 per cent of men with average income, respectively. These mandated schemes’ replacement rates are determined by individual workers’ contributions and their return rates. In the Japanese and Korean dualist pension systems, only mandated social insurance pension schemes and non-contributory ones are included to calculate the replacement rates. Corporate pension schemes are conceived of as a part of voluntary private pensions even though some are mandated occupational pensions. The replacement rates of these social pension insurance schemes for insured persons with average income are lower, set at 40.8 and 45.2 per cent, respectively. The introduction of basic pensions has generally supported low-wage earners. Overall, the low benefit levels of public pension schemes in Japan and Korea have to be compensated by sophisticated corporate pension schemes. By contrast, the social pension insurance schemes in Taiwan and China offer fairly generous benefits to retirees, at respective replacement rates of 73.2 and 84.7 per cent for average wage earners. However, the apparent generosity of retirement income in both cases disguises inherent inequality amongst different groups. Taiwan introduced the contributory NPI in 2009 in support of low-wage earners, but its benefit level remains insufficient for economic security. China's pension system features even more serious inequality amongst various occupational groups and across geographic regions, due to the fact that a substantial proportion of pension benefits depend on the financial support of local governments.

Table 2. Net replacement rates of pension benefits by earnings, 2013

Sources: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2009, 2013) and OECD Statistics. aTaiwan from Luxembourg Income Study (http://www.lisdatacenter.org/data-access/key-figures/) bHong Kong from Commission on Poverty (2017).

Table 2 further outlines the state of old-age poverty risk.Footnote 10 The East Asian countries under scrutiny offer a mixed picture. Japan has the lowest elderly poverty rate, whilst that of Korea is fairly high. A reasonable explanation is Japan's early introduction of public pensions that have matured over time, whereas Korea's NPI for private workers came much later in 1988. The same rationale holds for the puzzling phenomenon of high old-age poverty risks in statist pension systems despite their high net replacement rates. The expansion of pension schemes in Taiwan and China in recent decades had a delayed impact on poverty reduction. The individualist pension system features the highest old-age poverty risk, as retirees rely on very modest DC pension benefits. This issue has aroused considerable public concern about the hardship of elderly people in Hong Kong and Singapore (Ng, Reference Ng2011; Commission on Poverty, 2017). Although we would expect a negative relationship between the replacement rate and elderly poverty, Table 2 provides little ground for this assumption (cf. also Been et al., Reference Been, Caminada, Goudswaard and van Vliet2017). This incongruity is mainly due to the pubertal state of the East Asian pension systems that have yet to unfold their sustentative effects on old-age security.

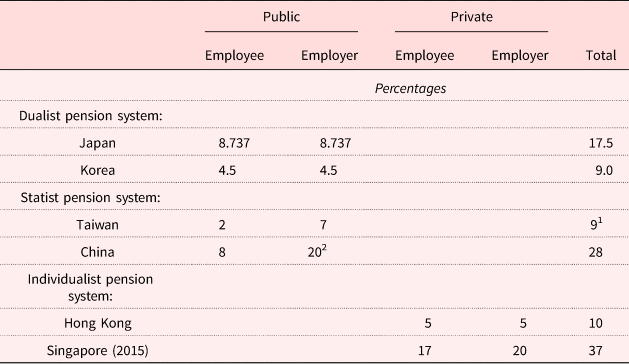

Tables 3 and 4 proceed to the comparison of the contribution rates and net pension wealth. Theoretically, a statist pension system with strong pension insurance would feature higher contribution rates and pension wealth than its individualist and dualist counterparts (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2003). However, the results in Table 3 are somewhat vague owing to the institutional disparity of the respective pension systems. For example, the contribution rate of the Singaporean CPF is almost four times that of Hong Kong's MPF, largely because it is a comprehensive scheme covering retirement, housing, health and education. Meanwhile, pensions in China have a higher contribution rate than those in Taiwan because the former assign heavy financial responsibility to enterprises. As for the different contribution rates between Japanese and Korean pension schemes, the aforementioned factor of varied institutional maturity still applies. The Korean pension system is relatively immature and prone to change.

Table 3. Mandatory pension contribution rates for an average worker in 2014

Notes: 1. The contribution rate for Labour Insurance was 10 per cent in 2014, jointly shared by employees, employers and the government. 2. This contribution rate may vary amongst the regions.

Sources: Singapore from https://www.cpf.gov.sg/. Hong Kong from http://www.mpfa.org.hk/. Taiwan from https://www.mol.gov.tw. Other countries from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2015).

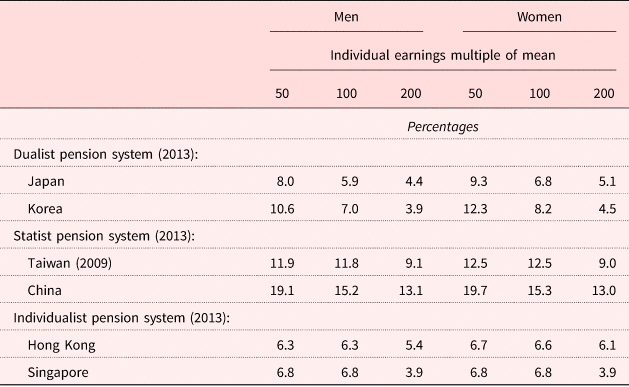

Table 4. Net pension wealth

As an indicator, net pension wealth is related to pension system liabilities, denoting the significance and size of mandatory public pensions (OECD, 2013: 32). Table 4 shows low net pension wealth in countries with individualist and dualist pension patterns. These pension systems feature lower net pension wealth than their social insurance counterparts. The above comparison points to a crucial institutional idiosyncrasy often overlooked by the scholarship of East Asian productivism, namely the predominance of mandatory public pensions in statist pension systems over dualist pension systems (cf. Holliday, Reference Holliday2000; Holliday and Wilding, Reference Holliday, Wilding, Holliday and Wilding2003). Indeed, our analysis highlights a subtle but crucial distinction between these two types in terms of the public–private mixes: social pension insurance schemes figure very differently between statist and dualist pension systems, implying various weight attached to private pensions.

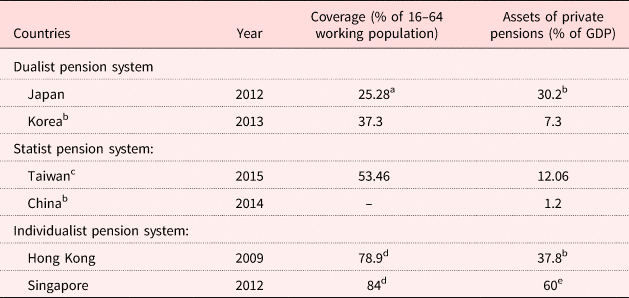

This point becomes clear with Table 5 which turns to the coverage of private pensions and the size of private pension funds. Coverage is measured as the percentage of the working population aged 16–64 covered by private pension plans, which indicates the role private pensions play in future retirement income (De Deken, 2013: 280). Hong Kong's MPF and the Singaporean CPF show high respective coverage rates of 78.9 and 84 per cent. The seemingly unimpressive coverage of private pensions in Japan (25.28%) and Korea (37.7%) is most likely due to missing data, including those of some corporate pensions based on labour contracts (Yamazaki, Reference Yamazaki1988; Nishinarita, Reference Nishinarita2009). For instance, despite its heavyweight, the Japanese corporate pension system does not account for the Retirement Allowance.Footnote 11 The same data inconsistency appears in statist pension systems as well, reflected in the unexpectedly high coverage of Taiwan's private pensions. The preceding section documents the transformation of Taiwanese corporate pensions from DB to DC individual accounts in 2005, leading to an increase in the coverage of corporate pensions, but this by no means enhances their impact because the contribution rates of the DC individual accounts remain low, ranging from 2 to 6 per cent of gross wages. This in turn leads to extremely low replacement rates – well below 10 per cent of wage levels during employment (Yeh, Reference Yeh2016). The discrepancy between coverage increase and low contribution rates in Taiwanese private pensions results from the reluctance amongst SMEs to bear non-wage labour costs.

Table 5. Coverage of private pensions and the size of private pension funds in East Asia

Note: GDP: Gross Domestic Product.

Sources: ahttps://www.pfa.or.jp/ and own calculation. bOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Statistic. chttp://www.mol.gov.tw/statistics/2445/ and own calculation. dOECD (2013). ehttp://www.pensionfundsonline.co.uk/content/country-profiles/singapore/101.

Table 5 also indicates the size of private pension assets, measured in terms of financial assets as a percentage of GDP, to evince the magnitude of private pensions as well as the degree of financialisation of retirement income (De Deken, Reference De Deken2013). Figures showing private pension assets relative to the national economy are higher in countries with individualist pension systems, amounting to 37.8 per cent in Hong Kong and 60 per cent in Singapore, respectively. This percentage gap is largely due to Hong Kong's more recent introduction of MPF, which has yet to accumulate assets comparable to those in Singapore. The huge size of private pension assets indicates the financialisation and individualisation of retirement risk exposure for the residents. When shifting attention to the dualist pension system, one would expect that their figures for private pension assets should stand somewhere between the individualist and statist pension systems. Japan's data indeed bear this out, but the Korean part appears baffling, partly because this country introduced a new corporate pension scheme in 2005. In addition, as more than two-thirds of workers are covered by the Korean DB corporate pensions, they are actually detrimental to capital accumulation (Phang, Reference Phang, Yang and Klassen2010; Yeh, Reference Yeh, Shi, Mok and Lau2014). Add these factors together, and the size of private pension assets in Korea ranks even lower than that of Taiwan. Finally, in statist arrangements, public pensions have crowded out private pensions, resulting in low private pension assets: 12.06 per cent for Taiwan and 1.2 per cent for China, where this disparity is due to the fact that although Taiwan did not introduce the DC Individual Retirement Account until 2005, it has accumulated a considerable amount of assets during the past decades.

To wrap up the above indicator comparison, Table 6 summarises the key features of the three pension patterns in East Asia. Despite a slight degree of inconsistency in some of the indicator results due to the evolving state of these pension systems, major contours of the three types stand out. In the individualist pension pattern, retirement income security is financialised and individualised through the institutionalisation of provident fund schemes which offer a replacement rate of around 40 per cent, but the role of the state is confined to the provision of means-tested assistance to the poor elderly. By contrast, the statist pattern emphasises the institutionalisation of social insurance pension schemes with high replacement rates, with the market playing a rather minor role in retirement income security. This assumes a significant role on the part of government in the financing and administration of overall pension insurance.

Table 6. Features of the three patterns of pension systems in East Asia

Notes: PAYG: pay-as-you-go. DC: defined contribution. DB: defined benefit.

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Most conspicuous is the dualist pension pattern of Japan and Korea which prioritises joint collaboration between public and private pensions for retirement income maintenance. Here the citizens’ old-age security hinges on her or his employment status as well as on the corporate pension entitlements. For those marginal workers who are denied access to the above benefits, the government steps in with universal basic pensions for minimum protection. A conceivable cleavage in old-age security emerges between the informal and marginal workers who rely on public basic pensions, and their colleagues in the formal employment sector, especially those in large enterprises, who receive generous corporate pensions on top of the public benefits.

Conclusion

Is there a distinctive East Asian approach towards old-age security? This paper presents a comparative policy analysis to identify three patterns of pension systems with pronounced institutional characteristics of public–private pension mixes. Whilst space limitations preclude a detailed account of how these pension systems have evolved over time, they are arguably the result of circumstances defined by local historical contexts (i.e. colonial legacy, nation-building, etc.), need for political legitimacy and modernisation (i.e. patronage and clientelist welfare), and structural transformations of state–society relationships (i.e. transition from authoritarianism to democracy). These distinct institutional configurations and policy legacies have key implications for the analysis of East Asian pension policy. Whilst the welfare regime approach assumes institutional isomorphism within East Asian welfare schemes, our analysis suggests moving away from conceptual holism to a far-reaching institutional analysis of pension policies that can yield fruitful insights into institutional evolution and policy outcomes. Our findings further supplement the conventional account on familialism in regard to the recent dynamic pension reforms in East Asia. Although families may still play a supportive role, this no longer restrains the state from enhancing involvement in the institutional expansion and regulatory refinement in all three patterns.

A further aspect concerns the issue of policy change. All the cases discussed here face similar challenges posed by population ageing and fiscal pressures, and pension reform will remain an important political consideration. The most daunting challenge facing the reform endeavours in East Asia is to strike a delicate balance to ensure programmatic financial sustainability whilst maintaining acceptable income levels. Bearing in mind the pension policy analyses of international organisations (Asian Development Bank, 2012; OECD, 2013; World Bank, 2016), the present study advances the research by highlighting the historical and institutional foundations of the East Asian pension systems. The existing institutional frameworks and policy effects are likely to impact the respective reform paths in the near future. Much depends on the interplay of given institutional constraints, actor constellations and their ideational contestations, as well as strategic manoeuvres.

Finally, students of pension policy in other parts of the world can learn from our comparative analysis that each pension pattern of East Asia features its own strengths and weaknesses. In terms of safeguarding old-age security, the statist pension system provides wide coverage and an adequate replacement rate, but faces mounting fiscal impasses that bring enormous political urgency to bear. The politics of pension reform in both Taiwan and China focus on rationalising existing pension schemes and redistributing the costs of pension austerity. However, accelerated demographic ageing and increased fiscal constraints make this task very demanding.

In contrast, individualist pension systems are largely immune to the looming fiscal collapse of public pensions since retirement income is and remains the sole responsibility of the residents and their families. The individualisation of old-age security comes at a high price with the haunting spectre of old-age poverty. This issue has begun to generate some political momentum in Hong Kong, with growing calls for some sort of universal basic pension. The Alliance for Universal Pension, a non-government association founded in 2004 and comprising representatives of various civic organisations, along with academics and ordinary citizens, have long advocated for the adoption of a universal old-age pension scheme in Hong Kong (Mok, Reference Mok and Izuhara2013). Reliance on individual savings further raises the impact of turbulent financial markets on retirees’ wealth. In a vivid example, the 2008 global financial crisis seriously depleted MPF funds, with aggregate net asset values dropping by nearly 20 per cent (Shi and Mok, Reference Shi and Mok2012). In the end, the government had to intervene indirectly by strengthening the role of social assistance for elderly people living in poverty.

If neither state- nor individual-based schemes provide good options, a dualist pension system would seem to offer great appeal. A first glance at Korea and Japan suggests such a co-existence of public and corporate pension schemes facilitates the maintenance of old-age security. However, the experiences of both countries point to some caveats as well. Occupational pensions are a double-edged sword in the sense that they provide additional retirement incomes to the workers on the premise that all enterprises could afford these non-wage expenditures. However, in practice, only companies of a certain size are in a position to provide such fringe benefits, and both countries are now experiencing a widespread dualisation trend in labour markets and social security between workers at large enterprises and their SME colleagues (as well as informal workers). Inequality in old-age security is the major reason why both countries have recently enacted basic pensions for all citizens. This may alleviate the hardship of old-age poverty, but it does little to ameliorate the inherent inequality.

Acknowledgements

Previous drafts of this paper were presented at the 24th World Congress of the International Political Science Association in 2016 in Poznań, Poland; as well as at the Department of Sociology, University of Bielefeld, Germany, in 2017. The authors thank the participants for their feedback, especially Professor Lutz Leisering, Professor Young-Jun Choi and Tobias Böger for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (S-JS, grant number MOST 107-2410-H-002-089).

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required.