Introduction

The New Zealand population is ageing due to increasing life expectancy and lower fertility rates. By 2050, an estimated 24 per cent of New Zealanders will be aged over 65 years (Statistics New Zealand, 2016). Better research and resources are required to support older people to age well in their preferred community (Dyall et al., Reference Dyall, Kerse, Hayman and Keeling2011) and sleep is a vital component of health in later life. Sleep has well-defined functions for supporting physical and mental wellbeing, including impacts on growth and immune systems, metabolism and cognitive functioning (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Frank, Wisor and Roy2016). In older adulthood, the neurophysiological mechanisms supporting efficient sleep typically degenerate and the prevalence of sleep disruptions increases (Ancoli-Israel et al., Reference Ancoli-Israel, Ayalon and Salzmann2008). More than a quarter of older New Zealanders report sleep problems (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Alpass and Stephens2015, Reference Gibson, Gander, Kepa, Moyes and Kerse2020) and poor sleep has been independently associated with poorer physical health, pain, depression and reduced quality of life (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Martinovich, Finkel, Harter and Zee2006; Alvaro et al., Reference Alvaro, Roberts and Harris2013; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Paine, Kepa, Dyall, Moyes and Kerse2016). Furthermore, those with sleep problems are significantly more likely to fall, or be admitted to hospital, compared with those without a sleep problem (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Paine, Kepa, Dyall, Moyes and Kerse2016). Disrupted sleep has also been identified as a risk factor for earlier mortality (Dew et al., Reference Dew, Hoch, Buysse, Monk, Begley, Houck, Hall, Kupfer and Reynolds2003; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Kepa, Moyes and Kerse2020). Despite the growing evidence concerning the importance of sleep, it is seldom considered in general health practice and aged care (Fyfield and Lim, Reference Fyfield and Lim2015; Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, 2019). Better recognition, management and treatment of sleep problems has major potential to improve the health and wellbeing of older people, facilitating independent living and wellness. Flow-on benefits for families, communities, health-care systems and aged residential care could be substantial (Fyfield and Lim, Reference Fyfield and Lim2015).

The concept of ‘sleep health’ focuses on the importance of sleep in maintaining health and wellbeing rather than on the presence or absence of disordered sleep (Buysse, Reference Buysse2014). Buysse's model includes subjective satisfaction with sleep as well as appropriate timing (i.e. sleeping at natural times of night), adequate duration (i.e. the recommended 7–8 hours), high efficiency (i.e. not spending too much time in bed awake) and sustained alertness during waking hours. Regularity is also an important consideration as waking up and falling asleep around same times each day have been associated with improved health outcomes (Buysse, Reference Buysse2014). Using this model, sleep can be better understood from a holistic perspective across cultures and promoted as part of strategies to live and age well in place.

Validated questionnaires provide useful insights into self-identified sleep patterns and symptoms. Objective monitoring provides quantitative data on sleep physiology and timing (Luik et al., Reference Luik, Zuurbier, Hofman, Van Someren and Tiemeier2013). However, qualitative inquiry is necessary to explore sleep health holistically, incorporating the psychosocial context in which sleep takes place and is mediated (Williams, Reference Williams2002; Buysse, Reference Buysse2014). This is important as the impact of the changing social context with ageing can be considerable. For example, sleep often changes in times of retirement, grief, loneliness, and with changing responsibilities such as grandparenting or care-giving for someone with a chronic medical condition. Furthermore, changing living situations and the capacity to be socially connected are also identified as important for maintaining satisfactory sleep health (Williams, Reference Williams2005; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Luszcz, Hislop and Moore2012; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander and Jones2014). The typically gradual nature of these changes may contribute to reduced identification or reporting of sleep problems, challenging the ability to actively support or intervene with factors affecting sleep (Ancoli-Israel, Reference Ancoli-Israel1997; Robbins et al., Reference Robbins, Grandner, Buxton, Hale, Buysse, Knutson, Patel, Troxel, Youngstedt, Czeisler and Jean-Louis2019). Qualitative inquiry is particularly useful for considering sleep among older populations and indigenous cultures. Sleep scales and measures that are typically used in research have mostly been validated in younger or Western populations and therefore are not necessarily appropriate or valid for Māori and older groups. A better understanding of changes to, and management of sleep within healthy ageing and with considering of context and beliefs, will inform the appropriate design and successful implementation of resources, interventions and health-care pathways.

Ethnic differences in sleep

In Aotearoa/New Zealand (AoNZ), ethnic disparities in sleep status have been identified. Māori (the indigenous people of AoNZ) are significantly more likely to be defined as having sleep problems compared with non-Māori. Including increased symptoms of insomnia, sleep disordered breathing, and unstable or suboptimal sleep timing (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Gander, Harris and Reid2004, Reference Paine, Harris and Mihaere2011, Reference Paine, Fink, Gander and Warman2014). Socio-economic disparities, compromised living and sleeping environments, poor physical and mental health, as well as reduced access to health care, also contribute to poor sleep (Paine and Gander, Reference Paine, Gander and Kushida2013). All these disparities can be attributed to living in a society which is not responsive to Māori values and needs, and where risks and benefits are unfairly distributed.

Most AoNZ research on disparities in sleep health has focused on younger adults (aged 20–59) (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Gander, Harris and Reid2004, Reference Paine, Harris and Mihaere2011, Reference Paine, Fink, Gander and Warman2014). In a study of New Zealanders of retirement age (55–72 years), Māori were identified as more likely to have a sleep disorder (odds ratio (OR) = 1.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.3–2.5) and to report feeling worn out (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.1–1.8) compared to non-Māori (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Alpass and Stephens2015). However, analyses of data concerning New Zealanders of advanced age (79–90 years) has found that sleep problems are less commonly reported among older Māori (26.3%) than older non-Māori (31.7%) (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Paine, Kepa, Dyall, Moyes and Kerse2016). Together, these findings suggest that demographic factors typically contributing to disparities in sleep health among younger Māori (e.g. socio-economic status and gender) are less relevant than health-related predictors among this much older sample, or that age-related changes in sleep are accepted or managed differently. For example, Māori who considered themselves problem sleepers endorsed more sleep-related symptoms than non-Māori, which may indicate that Māori have a higher threshold for what would be considered ‘problematic sleep’ (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Paine, Kepa, Dyall, Moyes and Kerse2016, Reference Gibson, Gander, Kepa, Moyes and Kerse2020). Together, sleep-related research from AoNZ corroborates the importance of sleep for overall health status whilst also suggesting that how sleep problems are understood and reported may vary with age and ethnicity. Cultural norms, social values and perceptions of health are unique among older Māori (Waldon, Reference Waldon2003), warranting a qualitative exploration into their sleep health.

The aim of this article was to explore the role of sleep for health, wellbeing and ageing among older people living in AoNZ, including the exploration of social-cultural factors and sleep-related beliefs, attitudes and experiences with ageing.

Methods

Interviews were conducted with 23 older people living in AoNZ. Equal representation of Māori and non-Māori participants was sought to ensure that diverse experiences of sleep health were represented.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited using email advertising and presentations to community organisations (e.g. Lions Clubs and The Māori Women's Welfare League) within the Wellington, Kāpiti and Manawatū regions, as well as through word-of-mouth. The inclusion criterion was being aged over 60 years to account for the disparity in life expectancy for Māori (Statistics New Zealand, 2012). Potential participants who showed interest were telephone-screened for eligibility and were excluded if they had either a known sleep disorder (one person with sleep apnoea was excluded) or a current and untreated mental health condition. Participants were provided with an information pack about the study as well as a consent form to be signed prior to the interview. The pack also included a brief questionnaire for verifying screening criteria and providing descriptive data. This included demographic details (age, gender, ethnicity – based on the NZ Census item which offers nine options in response to the question ‘Which ethnic group do you belong to?’), health conditions (Sangha et al., Reference Sangha, Stucki, Liang, Fossel and Katz2003), self-rated health (item 1 from the SF-12; Ware et al., Reference Ware, Kosinski and Keller1996), sleep duration and quality (items 4 and 9 from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Buysse et al., Reference Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman and Kupfer1989), as well as chronotype, using participants self-selected identity on a four-point scale ranging from ‘definite morning-type’ to ‘definite evening-type’ (item 6 from the revised Morning Eveningness Questionnaire; Adan and Almirall, Reference Adan and Almirall1991).

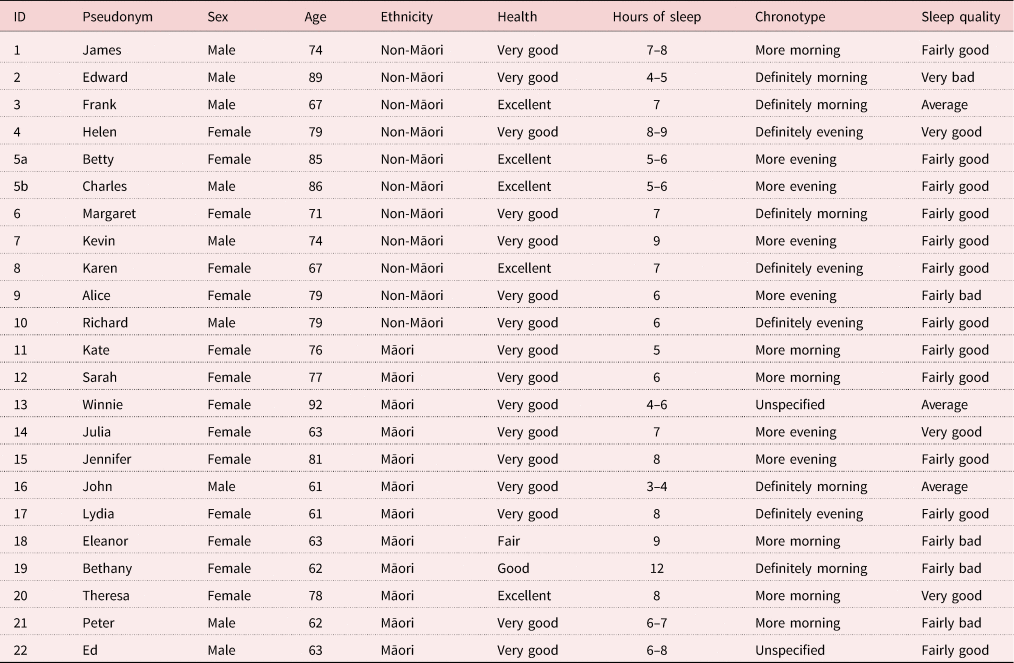

Interviews were conducted with 12 older people who identified as Māori (either solely or with another ethnicity) and 11 who identified as non-Māori (see Table 1). Participants mostly (92%) rated their health as ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ (with the others rating it as ‘fair’ or ‘good’), and 71 per cent rated their sleep as either ‘fairly good’ or ‘very good’. They reported sleeping a median of 6.5 hours per 24 hours (range = 3.5–12 hours) and were evenly distributed with regards to identifying as morning or evening ‘types’ (with 17% ‘definite evening types’ and 22% ‘definite morning types’).

Table 1. Participants' demographic details and self-rated health and sleep status

Engagement, recruitment, interviews, and analyses of data were conducted separately for Māori and non-Māori participants. A Māori research assistant and supervisor (GW and HT), competent in te reo me ona tikanga Māori (Māori language and customs) led the data collection for Māori participants. Interviews with non-Māori participants were facilitated by a research assistant and supervisor who were non-Māori (FC and RG). Interviews took place either at Massey University, in the participant's home, or in a community setting during December 2019. Participants were invited to bring their partner or spouse to join the interview. One interview included the participant's partner. All participants received an NZ $20 koha (approximately US $14 honorarium) in compensation for their gift of data and time. Interviews lasted between 20 and 70 minutes, were audio recorded and were transcribed verbatim using OtterAI software, followed by manual editing. Pseudonyms were chosen by participants and used to protect anonymity. Participants could opt to receive copies of recordings and transcripts as well as opt to have their data excluded from direct quotation in outputs. Four Māori participants opted for this level of confidentiality.

Interviews

Interviews focused on participants' experiences of sleep and changes that had occurred over their lifecourse. To ensure that similar topics were covered by all participants, interviews were semi-structured. However, questions remained open so that interviews were participant led. Questions were informed by Buysse's (Reference Buysse2014) dimensions of sleep health and covered the following general topics:

(1) Perception of current sleep (including duration, quality, regularity, efficiency, alertness, sleepiness, satisfaction, timing).

(2) Sleep over the lifecourse (factors that have caused sleep to change, perceived impact of ageing on sleep).

(3) Strategies for managing sleep (what they do currently, potential help-seeking behaviours, what they may find useful).

To maintain consistency, interviewers had a matrix of the dimensions of sleep health and cue questions on hand.

Analysis

A phenomenological approach was taken to the data which represented the experience, meanings and reality of the participants (Sokolowski, Reference Sokolowski2000). A data-driven thematic analysis of the transcripts was conducted individually by FC and GW who read, re-read and coded the transcripts independently of each other using NVivo 12 software. This approach allowed for basic themes to be constructed and illustrative quotes identified independently for both Māori and non-Māori interviews. These initial analyses were conducted separately to ensure that themes represented the experiences of members of each group. The purpose of the analysis was not to compare experiences, but to ensure each group was considered on their own terms. The research team then workshopped the broader patterns from the data, and organising themes were constructed. Themes underwent further reflexive discussions and revisions allowing for the extrapolation of data into broader global themes. This allowed for thematic networks relevant for the full sample to be created (Attride-Stirling, Reference Attride-Stirling2001) and underlying narratives identified. Here, narratives were in relation to the wider social expectations that people have about the practice of sleep in their lives, what changes might occur as they age, and how actions can or do shape their experiences of health across different aspects of their lives. These do not simply reflect their own personal experiences; they are also linked to scientific and lay understandings of sleep and older age that people use to interpret their own experiences.

Findings

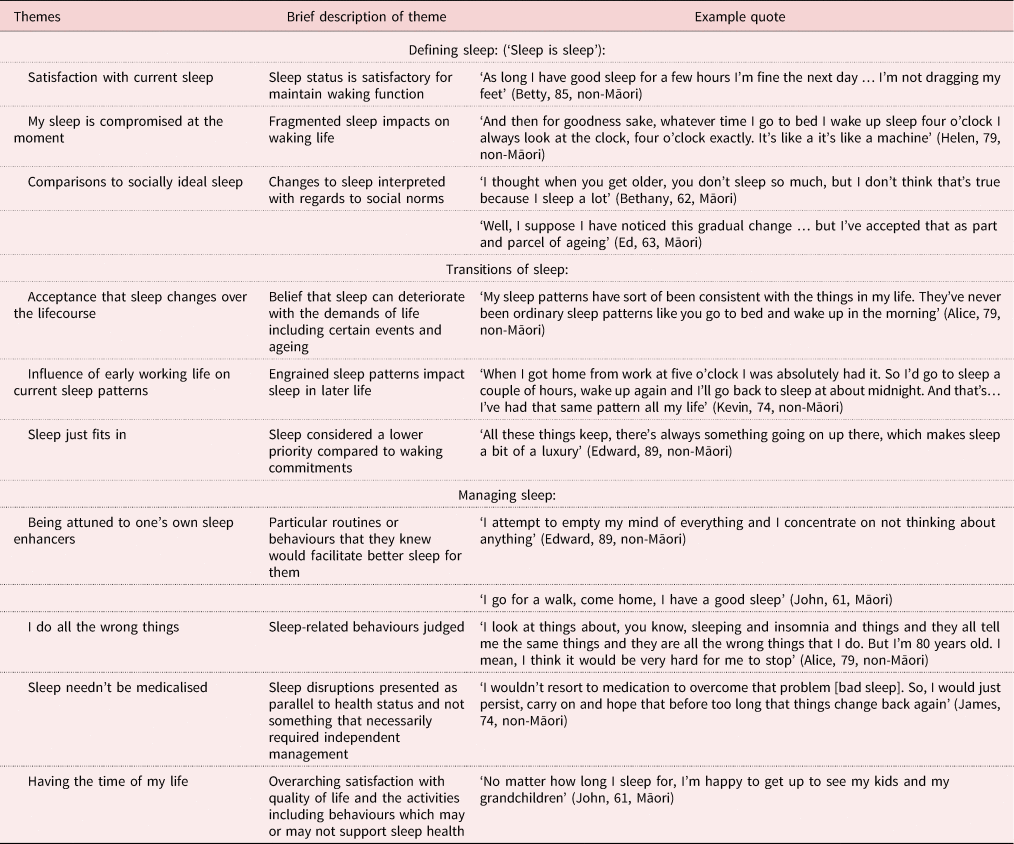

Themes from the interview data were constructed around the global topics of defining sleep, transitions of sleep, and strategies to manage sleep. Underlying narratives were also recognised which related to these topics and represent the shared social storylines about what sleep in older age might be like. These are illustrated in Table 2 and described below.

Table 2. Key themes, brief descriptions and quotes regarding sleep of older people of New Zealand

Defining sleep (‘sleep is sleep’)

Defining sleep included three organising themes regarding participants' perceptions of their current sleep status. These included: (a) satisfaction with current sleep, (b) feelings that sleep is compromised and (c) comparisons to a social perception of an ‘ideal’ sleep. These were organised within a more global theme of ‘sleep is sleep’ representing a clear attitude that participants had become accustomed to, and accepted, their sleep status regardless of how satisfied they were with it.

Satisfaction with current sleep status

Most participants reported a state of satisfaction with their sleep:

I never wake up wishing I had a good night's sleep. I feel that whatever sleep I do is a good night's sleep. (Winnie, 92, Māori)

Satisfaction was commonly related to the ability to achieve a certain number of hours, fall asleep easily and continue sleeping without disruptions:

I'm not really aware of what's happening in the world from about 11 pm to 6 am. (Julia, 63, Māori)

Sleep satisfaction was also associated with being alert enough to maintain activities or responsibilities in waking life.

Some participants recalled certain periods in their life of sleep loss and deprivation, which informed more positive perception and expectations of their current sleep status. Although satisfied, many also noted that their sleep was variable, that it ‘kind of tends to go up and down’ (Karen, 67, non-Māori), and this was largely accepted as being normal: ‘like everything else you have good nights and bad nights’ (Margaret, 71, non-Māori). The sleep environment was often provided as an example, particularly by Māori participants who shared experiences of negotiating sleep when sleeping communally on the marae (Māori meeting place) typically across several days and how this could have a brief impact on what was otherwise satisfactory sleep:

Your sleep definitely is different on a marae. Because there's coughing and snoring. You know, it wouldn't be my choice. Well, yeah. It's something that you do because of tikanga [traditional customs and practices], more than a choice. I mean now there's some things you can't choose to do can you, you have to go with the flow. (Jennifer, 81, Māori)

Satisfaction with sleep was intertwined with waking commitments and also expectations that less sleep was necessary as you age: ‘I reckon when you get older you don't sleep much, is that true?’ (Kate, 76, Māori). The thought that sleep was less necessary or would deteriorate with ageing or disease shaped participants' expectations regarding what constituted a ‘satisfactory’ sleep at this stage of life.

My sleep is compromised at the moment

Despite the sense of general satisfaction with sleep, many also noted compromise. Routine or early morning awakenings were common and described as occurring ‘like clockwork’ or being an ‘absolutely entrenched’ part of their sleep (Alice, 79, non-Māori). Although they have become accustomed to these awakenings, their occurrence was often frustrating. For others, fragmented sleep resulted in pronounced daytime sleepiness. Frank (67, non-Māori) noted his feeling ‘drowsy the whole day’ had led to him retiring from his job earlier than he had intended. Others felt their sleep was compromised because, despite the decent hours of sleep they were getting, it did not feel as good a quality as when they were younger. This compromised sleep was personally distressing and some described symptoms of sleep disordered breathing which was also disruptive to others:

Sometimes I'll wake up in the morning and I've been probably half awake and dreaming. And when I do wake up, my mouth is very dry which suggests that I have been snoring, and I have been told that when I do, it's very, very noisy and disturbs other people. (James, 74, non-Māori)

Typically, compromised or unsatisfactory sleep was presented as something that could not be improved. These changes were understood as general changes most people experienced as they age rather than changes in response to their own personal transitions over the lifecourse (discussed in the next theme).

Comparisons to socially ideal sleep

When describing their current sleep patterns, participants typically used their perceptions of social ideals as a benchmark. Comments such as ‘the so-called eight or nine hours sleep at night’ (James, 74, non-Māori) revealed that this number was both a shared representation of what people should be aiming for as a sleep goal, as well as a ‘so-called’ or arguable expectation that people resisted. This resistance to expectations that sleep should take a particular format was common. James also noted that long periods of sleep were ‘foreign’ to him. Jennifer justified her shorter or fragmented sleep by referring to too much sleep as a sign of laziness:

I don't sleep long, four, five hours. I think I like it though. You know if I sleep longer than that I think I'm lazy. (Jennifer, 81, Māori)

Richard had developed anxieties over his sleep and had ‘almost become obsessed’ with a sleep tracker watch which had drawn his attention to the purported parameters of his sleep. He compared his recordings to the norms of the device despite his reasonable sleep history and not having a full understanding of the technology:

largely I don't know the sort of details we were just talking about, you know, just exactly how they define those various things and how they have actually recognised in the measurements that might become but basically all they're measuring is heart rate … and I suppose the movement sensor determines how much you move… but even that is something that I'm not really sure exactly what it means … would you [I] recommend it to other people? I don't know. (Richard, 70, non-Māori)

The social ideals and perceived satisfaction with current sleep status were embedded in a narrative ‘that you don't need as much sleep when you're older’. Expectations that sleep would deteriorate with age or disease fed into the themes of what constitutes an ideal sleep for an older person. These were presented to justify their sleep status:

I think people get that idea into their head if they don't have an eight [hour] sleep when they used to, now they're not needing eight hours sleep, they're worried that there's something wrong with them because they're not having their eight hours sleep or that something will, you know, something will happen. In a negative way. (Betty, 85, non-Māori)

As such, personal sleep experiences were compared with, and interpreted against, narratives of idealised sleep patterns and changes that could be naturally attributed to ageing.

Transitions of sleep

General discussions regarding how sleep had transitioned over participants' lives led to the organising themes: (a) acceptance that sleep changes over the lifecourse, and (b) influence of early working life on current sleep patterns. These were informed by a common narrative of ‘sleep just fits in’.

Acceptance that sleep changes over the lifecourse

Lifecourse, in this instance, relates to the personal experience of a chronological order of biological and societal milestones such as birth, paid employment, family and care-giving responsibilities, retirement, grief and loss. An expectation that sleep would gradually change with the lifecourse was presented, as well as examples which illustrated how sleep was compromised during life events for different reasons:

People do say that the older you get the less sleep you need. But maybe it's less sleep they have rather than the less sleep you need. And I would say it's sort of frightening as you get older, in a way you sort of think I wonder what death's like. Not all the time. You seem to go to more tangi [tangihanga – Māori funeral], like when you're your age it will be engagements. And you know, there'll be weddings and then it might be christenings and blah, blah, blah. But when you get to a certain age it's funerals. Yeah. No, I'm quite satisfied with my sleeping pattern. And my waking pattern. If I know I've got something I want to do you know yeah. I'm really … I think I'm really happy. Well, I am really happy. There's lots of things I'd like, you know, to be the same as they were, but they never are, are they? You know, you go through different phases of growing up and life. (Jennifer, 81, Māori)

Comments such as Jennifer's above alluded to how life events, such as having children, acute illnesses and grief, were described as having a temporary but negative effect on sleeping patterns. These changes were acknowledged as ‘not a forever thing’ (Julia, 63, Māori). With regards to loss, participants reported that although fatigue could be considerable, it was a ‘normal part of the grief process’ (Charles, 86, non-Māori). Jennifer also noted the lasting impact of losing her husband whom she found sleeping next to ‘just wonderful’; she went on to describe her way of coping:

I do miss my husband, heaps. And I sometimes put the pillow in sideways so there's a lump in the bed and all that sort of … you know. Not always but sometimes. (Jennifer, 81, Māori)

Participants also reported that it was usual for other ailments to contribute to poor sleep patterns:

I can get up for the sake of getting up because I have to take several pills at certain times. (Eleanor, 63, Māori)

Transitions into retirement marked a prominent change in sleep patterns. Many participants reported that with retirement came a reduction of formal responsibilities which produced a flexible attitude around sleep – and making up for lost sleep – at times of disturbance:

[It's] a little bit of the luxury of not having to rush out of bed … I think people get anxious about not sleeping as well as they used to. Whereas, in fact, they don't have to sleep as well as they used to. (Charles, 86, non-Māori)

I used to get a bit upset then if I didn't have enough sleep, it used to worry me a bit. But it doesn't worry me now. If I don't sleep now, I'll sleep tomorrow or tonight. I'll make time for it. (Edward, 89, non-Māori)

These extracts locate changes in sleep patterns as linked to life transitions rather than biological changes as people age. Changing routines as people retire bring about flexibility for arranging sleep times across days differently from earlier in the lifecourse. Some participants simultaneously commented on feelings of guilt if they did not uphold commitments the next day regardless of how tired they felt:

I don't miss a lot of sleep. And I know when I need it. That's when I have a bit of a zzzz in the afternoon. But there's always something I should be doing. I should be out in the garden doing something. (Edward, 74, non-Māori)

Such extracts demonstrate the morality of sleep and sleep-timing which is linked to the major narrative that ‘sleep just fits in’. Rather than prioritising sleep, it is a process presented to occur when required by body and mind, or in-between waking commitments. Instead, the priority in older age is active involvement in social and family life:

I'm happy to just wake up every day to see my children, see my grandchildren. That's the bonus for me you know by the time I wake up, I'm always ready to do something. (John, 61, Māori)

Here John illustrates the factors which are important to him: living with, and for, the younger members of his family, and his gratitude to simply wake up and be actively engaged with them.

Influence of early working life on current sleep patterns

Although most participants had transitioned into retirement, many contended that their former working life and routines had contributed to long-lasting sleep patterns and behaviours. This was particularly the case for those who had been shift workers:

When I first started working I was shift working so I guess I think way back then I think I was … I thought I could handle it and I felt like I could. A few years ago I was surviving … I was getting about five hours sleep a night. Quite often I wake late, bit of a habit from my early years of working. I've often found of late that I do tend to drift off to sleep in the afternoons at the moment. It's quite easy for me to start … grab a nap. (Ed, 63, Māori)

Participants also noted that work acted as a notable stressor, which impacted their quality of sleep. Many emphasised that thinking about work would keep them awake at night or lead to many nightly awakenings. For some, these habits had continued into older age:

I remember all sorts of dreams. And the dreams, stupid thing which is the recurrence of events in the past. And even though I left my job 15 years ago, I still dream about going to work, the work environment, you know, arranging meetings and all that, the deadline reporting. (Frank, 67, non-Māori)

For this participant, the combined, stress, disturbed dreams and sleep loss contributed to his premature retirement:

It's just got me frustrated because the reason I left my job, early because when I went to meetings. And after. And if they have meeting at one-thirty. I'd be struggling because I kept napping away in the meeting room, even at that age. (Frank, 67, non-Māori)

Together, Frank's experiences highlight the bidirectional relationship between working life and sleep status and the lasting impact work experiences and stressors can have on sleep post-retirement.

Managing sleep

Discussions around sleep management, both in general and during times deemed problematic, conveyed the following themes: (a) being attuned to one's own sleep enhancers, (b) acknowledging doing all the wrong things, and (c) sleep needn't be medicalised. The major narrative that ‘sleep fits in’ continued here within the sense of ‘having the time of my life’, with ageing as the pinnacle and sleep as being managed alongside ageing.

Being attuned to one's own sleep enhancers

Sleep enhancers were defined as any bed or night-time routines that enabled participants to get into a ‘sleep mode’, as well as aids to help fall asleep or fall back to sleep if interrupted. Night-time routines were often habitual and for several participants this involved resting in front of the television each night. However, others acknowledged that they ‘endeavoured to be turning the telly off at nine-thirty’ (James, 74, non-Māori), with many indicating a preference for reading. These acts, alongside consuming certain foods or drinks, had become habitual to many for maintaining a consistent sleeping pattern. Many also acknowledged that physical activity during the day was useful:

If I've done some physical things during the day, then I find that I do go to sleep easily. (Karen, 67, non-Māori)

Despite this, when asked what techniques they might use to help during times of problematic sleep, physical activity was rarely acknowledged as a sleep aid.

Māori participants gave unique examples of sleep enhancers which were associated with social and cultural connection. For example, John related spending quality time with whānau (extended family) in the evening as key for relaxation:

Well my boy, he's native speaker in the language you know, and I talk about a lot of things, about things, about the old days … So we talk about things um, real deep things. My dad was a native speaker too, so I was bought up with the language too. So we talk about a lot of things you know and … sleeping, after we finish talking about things, deep things like our whakapapa [genealogy], I sleep alright. And that's the only way, I think that's how we, as Māori people you know, we talk about our whakapapa, our kuia, our koroua [elder female and male elders ancestors respectively], and its the way our bodies wind down and relax. (John, 61, Māori)

Some participants, like Winne (92, Māori), described their sleep-related behaviours as more ‘erratic’. These participants described behaviours that they would turn to if their sleep was interrupted or they were struggling to sleep. Many said that if they lay awake for a period of time they would, for example, ‘get up, read and watch TV or another programme on the computer or go for a walk’ (Kevin, 74, non-Māori). Device use was common, e.g. Frank (67, non-Māori) would ‘Just play around on my mobile phone’ if he woke. Mindfulness or relaxation techniques were actively used by some:

I attempt to empty my mind of everything and I concentrate on not thinking about anything. (Edward, 89, non-Māori)

I meditate while I'm in bed. And next minute, I'm asleep. (Ed, 63, Māori)

These sleep enhancers were individual to each person and described as engrained behaviours that they had used long term.

I do all the wrong things

Several participants reported that their sleep behaviours were problematic, admitting that ‘I do all the wrong things’ (Karen, 67, non-Māori) or that their night-time routine is ‘not conducive to good sleeping’ (Alice, 79, non-Māori). Alice went on to example her use of alcohol:

If there's people here and we're all having a drink and things, and I've drank a bit of, quite a bit of red wine, I have a good sleep quite often, you know. I don't feel great when I wake up but I do say quite often those sorts of things [which impact quality of sleep]. (Alice, 79, non-Māori)

Caffeine consumption and technology use were also common examples:

I make the mistake of looking at my phone, which I shouldn't do should I because you've got the light. (Margaret, 71, non-Māori)

Concurrently, it was clear that many were reluctant to change their activities around sleep. For example, Alice went on to note that it was a part of her personal routine and that in old age ‘it would be very hard for me to stop’. Some felt that changing their established routines wouldn't make a difference:

Well one of the things that I have always found is that caffeine has absolutely no effect on my sleep … So, I can have a cup of coffee late at night and it makes no difference. (Richard, 79, non-Māori)

Using computers or mobile phones had become a part of many sleep routines and was not always acknowledged as problematic or possibly reinforcing sleep problems, although it was recognised as being against sleep advice. When asked if it helped or hindered sleep during his early morning awakenings, Frank commented:

Using the mobile phone…? No, I don't think interfere my sleep because what I look at the mobile for that time, because I don't play games on it … so I do read the news on it. So, it is sort of things that I'm not really that concerned about and stupid thing is sometimes I open email some email messages coming in. No, I don't think it interferes. (Frank, 67, non-Māori)

Although this participant is clear that mobile phone use does not interfere with sleep, Frank's description acknowledges that reading emails in the early hours on his phone is potentially ‘stupid’. For him, the advice to avoid mobile phone usage is linked to playing games rather than using the phone productively or to access the news.

Sleep needn't be medicalised

A ‘sleep problem’ was often described in these interviews as being unable to go to sleep, or unable to get back to sleep after interruption. The majority of those interviewed did not believe such problems should be medicalised and they would not seek help or consult a health professional regarding their sleep. Some said they had never considered raising it, with disturbed sleep more often described as aligning with their general health status or as a symptom of a more tangible condition that, unless it became bad enough, would remain secondary:

I don't even know if I mentioned it to my doctor. I just, I just knew that it is one of the side effects of menopause just, I guess it wasn't bad enough, it wasn't happening, three or four nights in a row, and I wasn't turning into a zombie because of it so I didn't, it never pushed me far enough to do anything. (Karen, 67, non-Māori)

Nevertheless, a few had previously sought help from a professional, agreeing that:

I would listen to the advice given, and just find the will to stick to it, my sleeping pattern might get better. (Eleanor, 63, Māori)

This indicates that good sleep is less about medical intervention and more about following general sleep advice.

Māori were more likely to note that times of wakefulness offered a quiet time of life reflection (as opposed to inconvenience which was the typical narrative within the non-Māori cohort). Similarly, night awakenings or vivid dreams were presented by some as facilitating capacity for creative endeavours, or positive spiritual connections with those who had died. For example, John noted that at times of waking in the early hours of the morning:

I'll pull out my book, because I'm a carver, so drawing pictures of a taiaha, tewhatewha or patu [traditional Māori weapons] and doing different designs. I think that time of the morning is good for me to work - no one around, can't hear anyone. But once, come on daylight, I'm tired again. (John, 61, Māori)

John also noted that:

I think a lot of people can communicate through sleep. Like myself with my people that have gone before me, I communicate with them through sleep. Sometimes I say to my son, ‘your Mother was with me last night’ when I was asleep … It's like my mum, she comes back, and she comes to see me. And I'm asleep. I'm fine with that sort of thing it's just I've been brought up around it, not to be frightened. (John, 61, Māori)

These examples indicate that periods of wakefulness may not be so readily presented as a problem which necessarily needs rectifying.

When asked about their attitudes towards sleeping medication, responses varied. A minority were currently using or had used sleeping medications in the past. However, these were used with caution, with one participant stating that they ‘meticulously cut them in half’ (Betty, 85, non-Māori). Some were open to trying sleep medications if they experienced a long bout of insomnia but the majority were averse to the idea of sleeping medications or did not ‘believe in taking anything’ (Ed, 63, Māori), which suggested stigma attached to their use:

There have been times when I can tell you, quite frankly that I would have loved to have gone to a doctor and asked for some sleeping pills. But then I'd be too embarrassed to do it and then I'd be too embarrassed to take them to the chemist for some reason. (Alice, 78, non-Māori)

Embarrassment around the use of medications for sleep indicates a degree of social taboo around medialising sleep; that to treat it formally indicates illness or failure to self-manage sleep, which contradicts the expectation that sleep ought to come naturally.

Having the time of my life

The themes of sleep management were connected to an overarching narrative of ‘having the time of my life’. For example, most participants presented themselves as being successful in regard to their goals (e.g. health, family, finances) and that they were satisfied with where they were in life, including their sleep, regardless of how bad it may appear in comparison to social norms. Contentment with waking life contributed to the unwillingness to change what they enjoyed in order to enhance sleep. Examples include staying up late to enjoy visitors, books, television or drinking alcohol. Some Māori participants were particularly reflective with regards to gratitude concerning their growth and experiences of being an older member of the whānau (extended family), especially their ability to remain actively engaged and maintain responsibilities regardless of their sleeping or waking health status:

For me, being with my son and being around my children because, their first language is Māori, all my six grandchildren. And we don't speak English to them. And so I'm happy, happy being here now. So, no matter how long I sleep for, I'm happy to get up to see my kids and my grandchildren. (John, 61, Māori)

There was also common acknowledgment that whānau responsibilities are prioritised. This was particularly clear during times of loss and tangihanga (Māori funeral) where sleep would be compromised for this time of life. For example, when asked how much sleep she felt she was getting at the moment, Winne replied:

Insufficient. It's not predictable. I wish I could say … See, since about last Thursday. Oh, no. Last week on Monday, X died, didn't she or whatever day it was she came to X. So, we had that exciting time there with all those people … on … our marae. And then see herself you know who's grown up in X when she was young, well she … How do you like to be 48 and dead, and the last 11 years battling cancer, you know?! So so that was vital that we stay on hand to be there for the people coming to X and so that was erratic. And then what happened here like yesterday attended to funeral services one in X and then came back because we had a person coming on to this marae … So when you ask me that question, I could make up an answer, but the answer is – unpredictable and very much concerned [with daily responsibilities]. (Winne, 92, Māori)

Here Winne illustrates how she could not put a number on her typical sleep duration, her time is governed by her strong waking responsibilities which during this busy time of her life means less-predictable sleep. 'Having the time of my life' was about embracing this period and carrying on in recognition that time with others is precious. By implication, time spent sleeping is time not spent connecting with others and completing important tasks.

Discussion

This study demonstrated the complexity of sleep during later life among a group without diagnosed sleep disorders. Sleep reflected both changes with ageing and changes brought about in response to lifecourse transitions. Themes of sleep change and management were presented within common narratives of a reduced need for sleep with ageing, fitting sleep in amongst other responsibilities or health, and prioritising life around family or other behaviours which were represented as important for successful ageing.

Themes within these data help corroborate and explain the findings of previous quantitative studies concerning sleep among New Zealanders. These indicate that, despite disparities of sleep health identified among Māori (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Gander, Harris and Reid2004) and well-recognised physiological and pathological threats to sleep health in later life (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, O'Driscoll, Ali, Jordan, Trinder and Malhotra2010), the incidence of reporting sleep problems does not appear to rise dramatically with age and ethnic disparities of sleep health are less quantitatively evident (Grandner et al., Reference Grandner, Martin, Patel, Jackson, Gehrman, Pien, Perlis, Xie, Sha, Weaver and Gooneratne2012; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander, Alpass and Stephens2015, Reference Gibson, Gander, Paine, Kepa, Dyall, Moyes and Kerse2016, Reference Gibson, Gander, Kepa, Moyes and Kerse2020). This qualitative study shows that a resistance to defining sleep as problematic may be founded in underlying beliefs and expectations that sleep deterioration is normal with ageing and that little can or needs to be done to resolve sleep problems. Satisfaction with current sleep was typically associated with the ability to function during the day regardless of what happened with sleep overnight. Typically, participants compared their sleep to that of their former self as well as what was socially expected. This was particularly the case regarding the amount and timing of sleep as well as stigma around napping and use of sedating medications. These findings add to the growing literature concerning attitudes and myths around sleep health during a time when sleep is increasingly being commodified and public health messages are inconsistent (Williams and Boden, Reference Williams and Boden2004; Venn and Arber, Reference Venn and Arber2012; Robbins et al., Reference Robbins, Grandner, Buxton, Hale, Buysse, Knutson, Patel, Troxel, Youngstedt, Czeisler and Jean-Louis2019). It is important to strengthen messages around the role of sleep in supporting healthy ageing, rather than viewing sleep as something which should be expected to decline (Vitiello, Reference Vitiello2009).

Some participants described what would be considered poor ‘sleep hygiene’ behaviours (Irish et al., Reference Irish, Kline, Gunn, Buysse and Hall2015). For example, using light-emitting devices after bedtime or poor timing of consumption of sugary foods and caffeinated or alcoholic drinks. However, many simultaneously presented a reluctance to change regardless of their awareness of the impact of such behaviours on their sleep. Furthermore, while participants were knowledgeable with regards to factors which facilitated better sleep (such as physical activities) they seldom noted such activities as a strategy they would consider for improving their sleep at times of disruption. As with previous studies among older people in England (Venn and Arber, Reference Venn and Arber2011, Reference Venn and Arber2012), an awareness of the importance of sleep for overall health was presented, yet sleep was not something considered from a medical perspective or as something which needed intervention. Furthermore, how these older people defined their sleep was influenced by their former experiences and current responsibilities. Together, these findings represent a desire for control and autonomy for sleep and the behaviours surrounding sleeping which, as we age, increasingly become a part of a person's habits and identity.

There were no clear differences in themes noted between genders. This is contrary to previous studies (Meadows, Reference Meadows2008; Venn et al., Reference Venn, Meadows and Arber2013) and may be associated with the lower number of men in the present study (particularly in the Māori cohort). Subtle cultural differences were noted; older Māori seemed less likely to pathologise sleep disruptions and rather embrace times of sleeplessness as facilitating spiritual connection, quiet mindfulness, or creativity. This may reflect the multi-dimensional, holistic perspective Māori typically have of health, in which dimensions of wairua (spiritual) and hinengaro (mental) are considered cornerstones of health, alongside whānau (extended family) and tinana (body) (Durie, Reference Durie1985; Valentine et al., Reference Valentine, Tassell-Mataamua and Flett2017). Cultural engagement has been identified as an independent predictor of greater physical health and quality of life among older Māori (Dyall et al., Reference Dyall, Kēpa, Teh, Mules, Moyes, Wham, Hayman, Connolly, Wilkinson, Keeling, Loughlin, Jatrana and Kerse2014). Furthermore, attitudes around ageing and kaumātua (respected older Māori) mean ‘that older Māori are able to pursue fruitful lives and occupy valuable roles, largely because of their many years of experience’ (Waldon, Reference Waldon2003: 169) as opposed to ageing being defined by levels of hardship or illness. The present findings add to this, suggesting that sleep-related beliefs and practices as well as definitions of sleep ‘problems’ may have nuanced differences among Māori and therefore a unique approach to sleep is recommended.

A general resistance to over-medicalise sleep was presented, as well as a reduced awareness of the association between poor sleep and other health outcomes. It is useful for health-care professionals to consider these findings when supporting older people with their sleep. It may not be helpful to instil fear around sleep duration and timing; health promotion efforts which do this may have paradoxical effects on attitudes and behaviours to support healthy change (Williams and Boden, Reference Williams and Boden2004; Simpson, Reference Simpson2017). Instead, a tailored approach is recommended, with services for older people acknowledging the wider context of their lives which may impact sleep. For example, motivational sleep interviews could provide opportunity for reflection and discussion on sleep and consideration of future changes. This indicates a potential for developing positive sleep health resources and processes in health care which could empower people to understand and support their sleep with ageing or co-design appropriate interventions with health-care professionals. Themes around the development of negative sleep habits in younger periods of life corroborate the need for messaging which highlights the importance of sleep across the lifecourse.

When considering these findings, it is important to appreciate the limitations. The act of screening participants for their health and sleep status may have primed some participants regarding how they presented their sleep status to the researchers. To counter this, the analysis acknowledged the role of these health and sleep measurement tools in shaping the thematic findings. Interviews from Māori and non-Māori participants were conducted and analysed in parallel. Working themes then underwent further analyses and workshopping amongst the full research team and, given the strong similarities across the participants, were collated and presented as unified thematic network. Agreement in the key themes between the two interviewers and participant groups supports validity of themes within the data whilst allowing for the representation of nuanced views and descriptions of sleep with ageing among older Māori as well as non-Māori.

This convenience sample involved participants who considered themselves in good health and all lived in the same region. This study has therefore provided a snapshot of what sleep is like among healthy older New Zealanders. This health status may have influenced participant's perceptions around changes to sleep, the medicalisation of sleep and a reluctance to identify with sleep as problematic while they are otherwise ‘ageing well’. Those with physical or mental health conditions, or with limited capacity because of their health or living situation, are not represented here. Such populations have been identified as having greater sleep disruptions (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, O'Driscoll, Ali, Jordan, Trinder and Malhotra2010; Grandner et al., Reference Grandner, Martin, Patel, Jackson, Gehrman, Pien, Perlis, Xie, Sha, Weaver and Gooneratne2012; Gibson and Gander, Reference Gibson and Gander2020) and therefore would likely provide different themes regarding their sleep, its impact on waking life and its management. An example of this can be found in the unique themes of sleep disturbances constructed from focus groups with New Zealanders with dementia and their family carers. However, even in this situation, sleep problems were normalised as part and parcel of ageing and living with dementia (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Gander and Jones2014).

Sleep is considered to be mediated socially; our understandings of sleep are shaped by those we live with (Meadows et al., Reference Meadows, Williams, Gabe, Coveney, Arber, Cappuccio, Miller and Lockley2018). How older people sleep in the context of the wider family is also important, particularly among older Māori and Pacific peoples who are more likely to live and function around the schedules of younger family members (Du Plessis and Diggelmann, Reference Du Plessis and Diggelmann2018). In the current study, participants were welcome to bring a spouse or family member to the interview, however, only one did. Future research may focus on whānau/family sleeping to understand how the sleep of older people is mediated by other members of their household in order to contribute to a broader ecological model of sleep in AoNZ society.

This research was conducted with those aged over 60 years and linked the findings to both experiences of ageing and transitions across the lifecourse. The themes identified appear to be socially and historically specific and reflect the experiences and circumstances of this generation. Differences in family formations and alterations in gendered expectations across lifecourse transitions will mean that sleep will likely differ among future cohorts. The rapid changes in technology and media around sleep tracking and commercialisation, as well as flexible work patterns, mean that future generations may develop different views on sleep and sleep health, in combination with other dimensions of life and health, as they age. Public health messaging around the importance of sleep with ageing and across generations is key. To be effective, is has to be tailored to the varying attitudes, beliefs and contexts of different target audiences.

Conclusion

This qualitative exploration into the sleep of older Māori and non-Maori in AoNZ indicates that sleep status was defined in relation to personal history, and social and cultural expectations. Sleep was reported to have typically undergone changes across life transitions and was expected to deteriorate with ageing. The majority accepted sleep disruptions as normal and were not overly concerned so long as their waking function remained satisfactory. Sleep was fitted in around busy lives and responsibilities of these older people who typically believed they did not need as much sleep as when they were younger. Some Māori participants accessed cultural explanations to normalise their experiences and provided novel interpretations of sleep, dreaming and periods of sleeplessness as providing opportunity for spiritual and cultural connection. The maintenance of good sleep was acknowledged as supporting physical and mental health, and participants had an awareness of their own personal sleep enhancers. Yet a resistance to adapting sleep practices was simultaneously presented during a time when many prioritised their waking life, embracing the roles, responsibilities and luxuries that they were enjoying in older age.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the older New Zealanders who took the time to share their experiences; also, the Wellington, Kāpiti and Manawatū regional offices associated with the Māori Women's Welfare League and NZ Lions Clubs and who helped promote this research.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (Emerging Researcher grant number 18/621).

Ethical standards

This project was approved by the Massey University Human Ethics Committee: Southern A (19/61).