Introduction

Residential care facilities (RCFs) provide complex, 24-hour, long-term care for older adults with mental and/or physical impairments. RCFs do not provide specialised care, such as addiction treatment, but they provide a home for frail older adults who are unable to take care of themselves anymore due to their mental and/or physical impairments. Residents living in RCFs are highly dependent on their environment and their care-givers are essential, physically and psychologically (Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018).

Care for older adults has been shifting from the biomedical care model towards a person-centred model of care (Koren, Reference Koren2010). The predominant aim within the biomedical model was care to enhance safety, health and longevity for residents by focusing on health outcomes (White-Chu et al., Reference White-Chu, Graves, Godfrey, Bonner and Sloane2009). The traditional model was disease-focused and impersonal (Morgan and Yoder, Reference Morgan and Yoder2012). To incorporate the residents’ personal experiences of wellbeing and dignity, this model was gradually replaced with the person-centred model of care (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Winblad and Sandman2008). The international literature provides a range of definitions of person-centred care (PCC). PCC is a holistic, biopsychosocial model of care that is responsive to the needs and values of people, and gaining an understanding of these values is a central aspect of PCC in practice (McCormack, Reference McCormack2004; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2018). This model of care focuses on the wellbeing and quality of life of residents and involves residents by offering them choices and shared decision making to maximise each individual's potential (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Winblad and Sandman2008; Brownie and Nancarrow, Reference Brownie and Nancarrow2013; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2018). PCC in practice includes, for example, offering choices to residents concerning personal matters, such as determining one's own bedtime and food and beverage choices (Koren, Reference Koren2010). According to Fazio et al. (Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018), PCC has psychosocial benefits for residents and staff, exemplified in a decrease in agitation and improved quality of life in residents and reduced stress in staff.

When PCC is implemented regarding substance use and misuse, practical and ethical issues may arise for care professionals balancing residents’ personal autonomy with the health and safety of all residents (Lester and Kohen, Reference Lester and Kohen2008). According to the ‘dignity of risk’ principle, residents should be able to have choices to fulfil their wishes, even if this results in adverse outcomes for themselves (Ibrahim and Davis, Reference Ibrahim and Davis2013). This complements the concept of PCC and means that residents should be offered informed choices and involvement in decision making regarding their substance use. In general, substance use, such as alcohol use and misuse, was reported as a potential hidden health and social problem in older adults (Iparraguirre, Reference Iparraguirre2015). When residents are known with current substance misuse or have a history of misuse, implementing PCC means acting in the interest of the resident and his or her environment. This includes a consideration of the potential harm and the potential beneficial effects such as a possible increase in social participation (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Olanrewaju, Cowan, Brayne and Lafortune2018). Therefore, implementing PCC could create challenges for care professionals when the needs and values of residents result in adverse outcomes.

A previous systematic review studied the prevalence of alcohol and substance misuse among community-dwelling older adults and found that substance misuse is common but underdiagnosed (Fingerhood, Reference Fingerhood2000). Alcohol misuse was most common, but prescriptive sedative misuse was also found (Fingerhood, Reference Fingerhood2000). However, this study did not focus on older adults living in RCFs, where the dependency of the environment is eminent. In addition, the review solely studied substance misuse and did not include substance use in general. The aim of the current study is to review what is known about substance use and misuse, regarding alcohol, tobacco or non-prescribed drugs, among older adults living in RCFs. Moreover, this review aimed to identify what is important to study in future research to enhance PCC in cases in which residents wish to choose unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol.

Methods

Study design

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used as a guideline to conduct this review (see the online supplementary material; Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O'Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty, Lewin, Godfrey, Macdonald, Langlois, Soares-Weiser, Moriarty, Clifford, Tunçalp and Straus2018). Scientific papers were gathered using six databases: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL, Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts, as most relevant publications are expected to be found in medical, psychological, nursing and sociologically oriented journals.

Search strategy

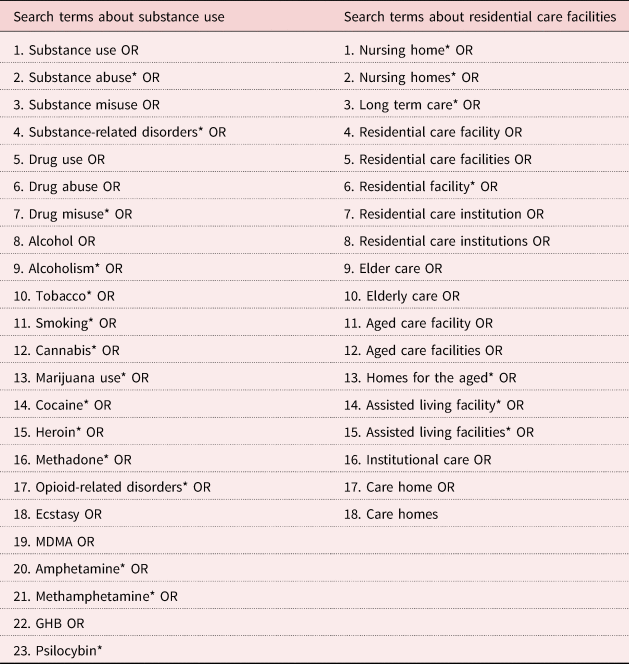

The search was performed on all six databases on 26 February 2019 and updated on 6 August 2019. The search string was designed based on two themes (Table 1). The first terms were related to substance use. Substance use in this review includes all kinds of use or misuse of all substances, except for medically prescribed medication. These were excluded because the use of prescribed medication is not voluntary and misuse of prescribed medication is minimal in RCFs because care professionals are responsible for administration of this medication. The second terms relate to RCFs for older adults. In this review, studies are included when performed in facilities that provide intensive and complex inpatient 24/7 long-term care for older adults with mental and/or physical impairments. These facilities provide care to older adults representing the general population, which might include a minority of older adults with substance use disorders. This specific sub-group is not the main focus of this review. Facilities which provide specialised psychiatric or addiction care were excluded, e.g. Veteran Affairs settings were excluded from this review due to different demographic features and more prevalent mental health problems in this population. Veteran Affairs settings consist of a largely male population with a high prevalence of substance use disorders (Lemke and Schaefer, Reference Lemke and Schaefer2012).

Table 1. Search terms

a*MeSH terms

The search was limited to peer-reviewed papers, written in English. There was no date limit set as an exclusion criterion to provide a complete and broad overview.

Study selection

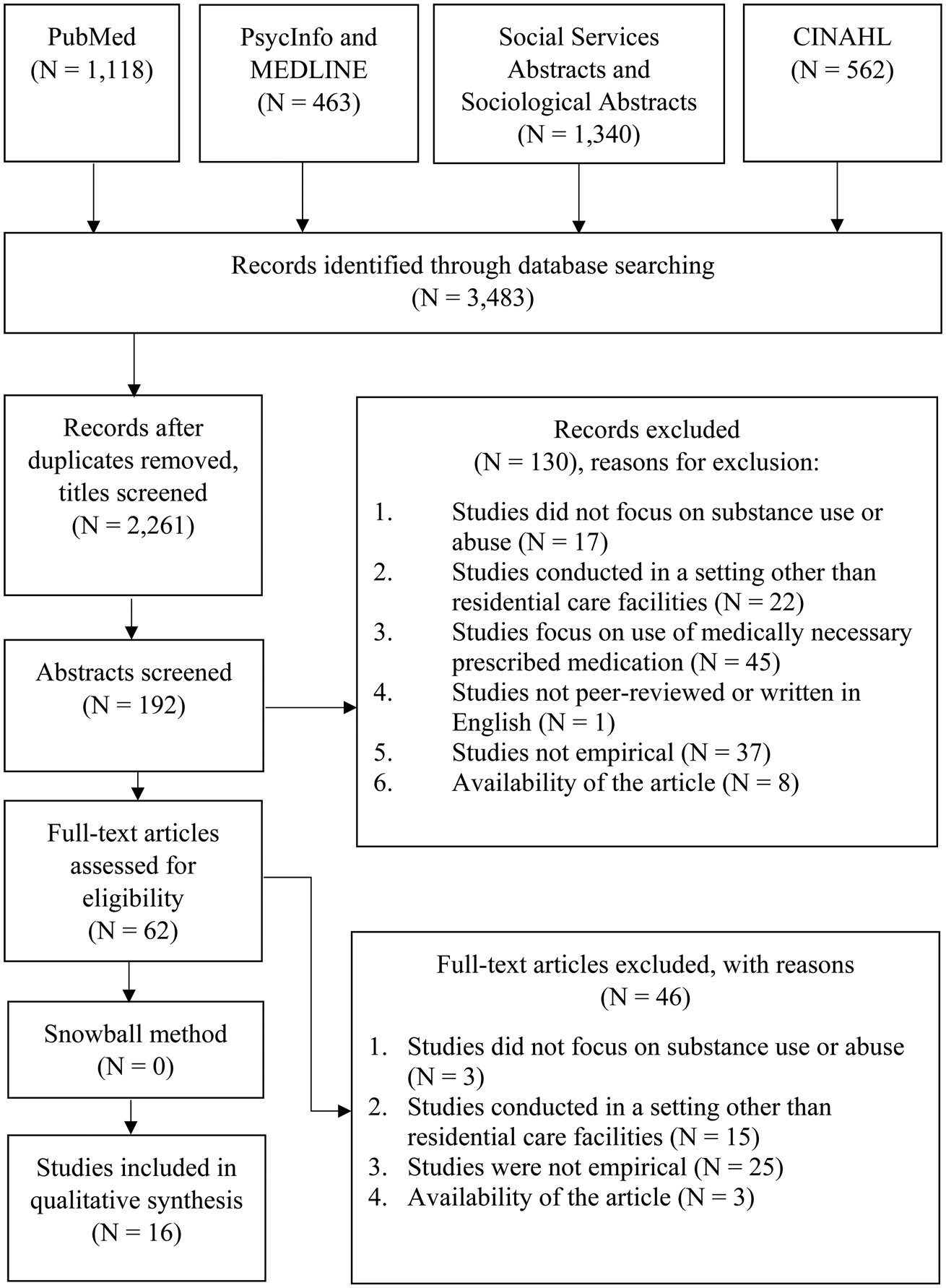

The study selection was performed based on the exclusion criteria presented in Table 2. The selection process is presented in Figure 1. First, all duplicates were removed. The remaining papers were screened by title by one researcher, LG. When there was no clarity whether to include or exclude a paper, the paper was included to the abstract screening. Second, the abstracts of five papers were screened by three researchers independently (LG, MJ and TR) to increase inter-rater reliability in order to enhance rigour and trust. Third, of the remaining papers, the abstracts were screened by three researchers independently (LG, MJ and TR) and when there was no consensus, the paper was included in the full-text screening. Fourth, the screening of the full texts was performed by three researchers independently (LG, MJ and TR). When there was no consensus, after discussion between two researchers, the third researcher was included in the discussion. This was necessary for one paper. Finally, the snowball method was conducted to check the references of the included papers; however, this did not result in any additional papers.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the selection process.

Table 2. Exclusion criteria

Quality assessment

The quality of the included papers was assessed by three researchers independently (LG, MJ and TR) using the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT; Hong et al. Reference Hong, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O'Cathain, Rousseau, Vedel and Pluye2018). The MMAT was chosen because it enables the comparison of studies with different study designs: qualitative, randomised controlled, non-randomised, quantitative descriptive and mixed methods (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O'Cathain, Rousseau, Vedel and Pluye2018). The MMAT consists of two screening questions and five methodological quality criteria for the five different study designs.

Data extraction and analysis

A qualitative approach for data extraction and analysis was chosen due to the broad range of study designs of the included papers. This qualitative approach consisted of a data-extraction form, which was filled in by three researchers independently (LG, MJ and TR). The data-extraction form included: title, author, year, country, aim, research question, included substances, study design, sample size, study population, setting, outcome variables, main results and limitations of each paper. Three researchers independently analysed the results qualitatively (LG, MJ and TR), resulting in a comparison of these results and a description of contrasts and similarities. Three recurrent themes were found: prevalence, policies and care professionals. These themes will be elaborated in the Results section.

Results

Study characteristics

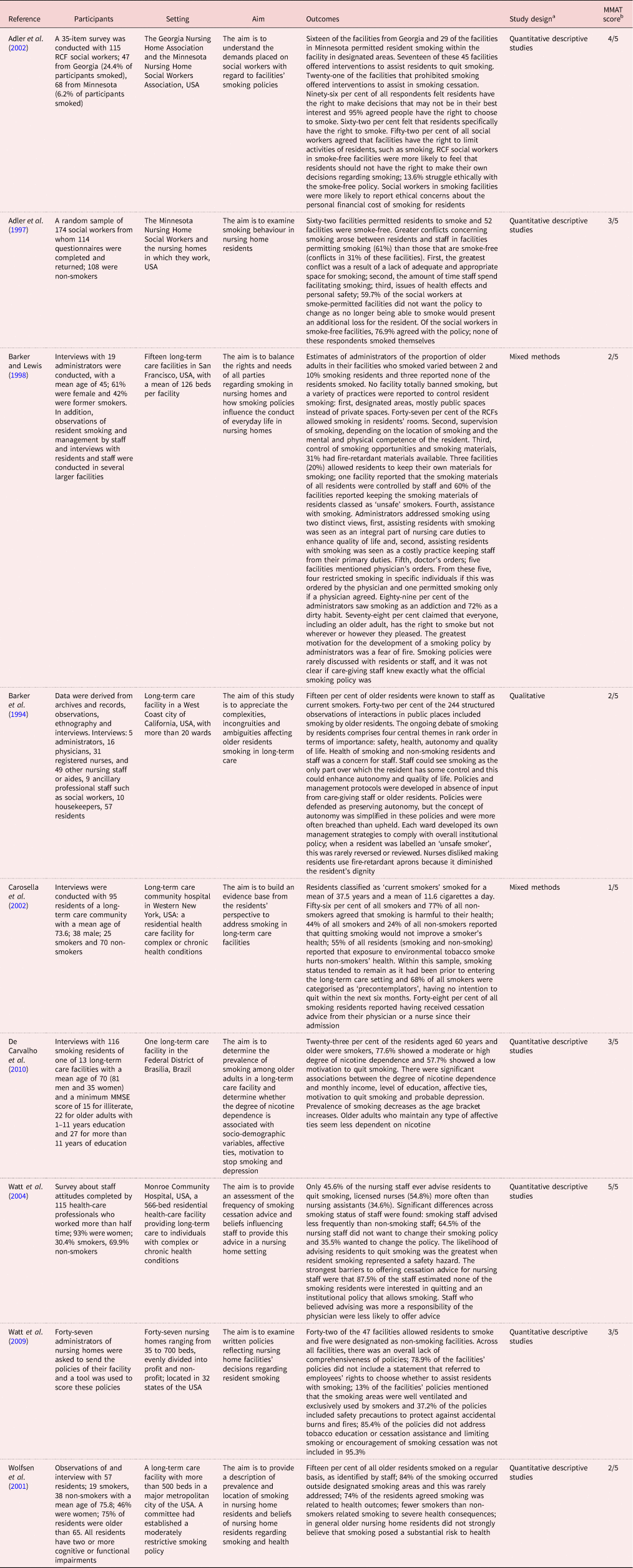

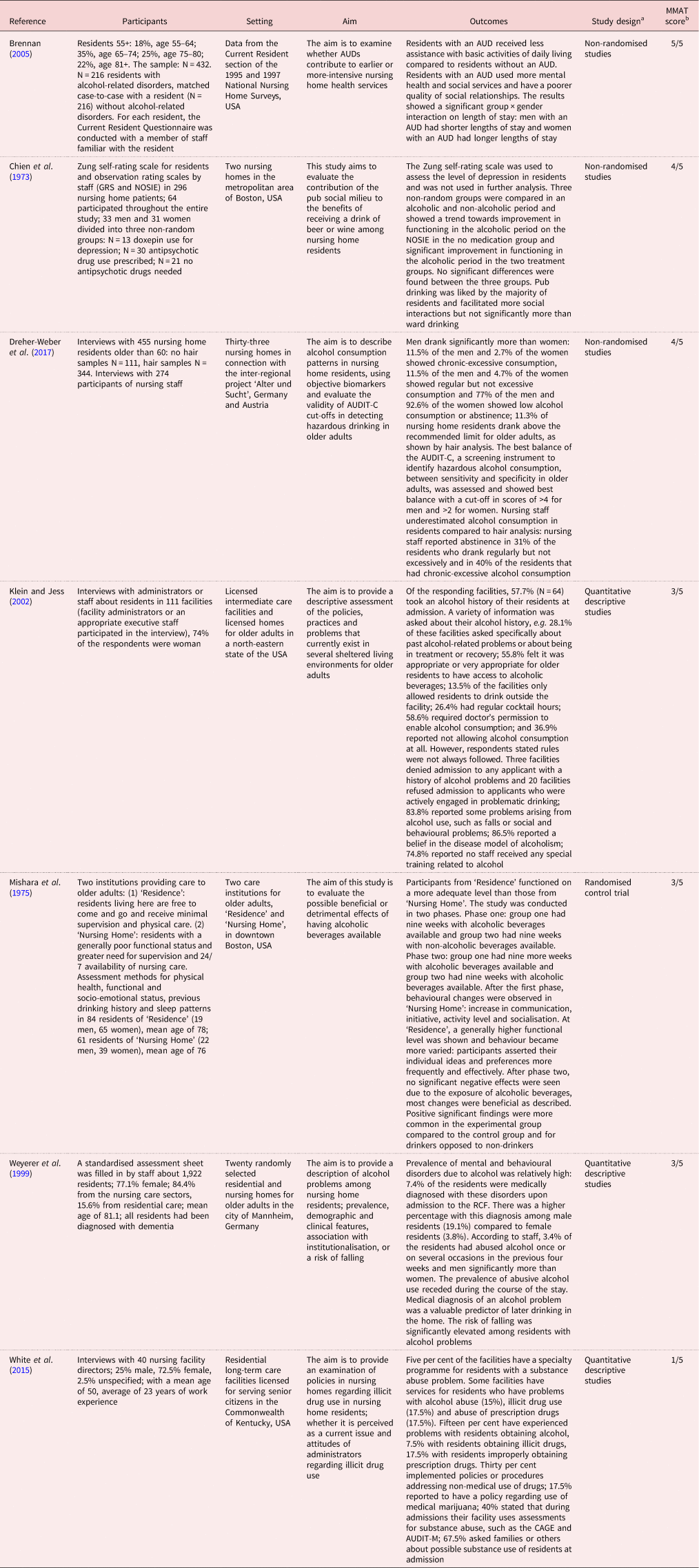

From the 2,261 papers initially found, 16 papers were included in the data-extraction procedure, as presented in Figure 1. The study characteristics are described in Tables 3 and 4. The included studies were conducted in five different countries. One study was conducted in two countries (Germany and Austria), the other studies were conducted in one country: the United States of America (N = 11), the United Kingdom (N = 2), Germany (N = 2), Austria (N = 1), and Brazil (N = 1). The study designs were quantitative (N = 13), qualitative (N = 1), and mixed methods (N = 2), with sample sizes ranging from 19 to 1,922 participants. The drugs assessed in these studies were tobacco (N = 9), alcohol (N = 6) and illicit drugs (N = 1). The studies were conducted between 1973 and 2017. The included papers regarding tobacco use were conducted between 1994 and 2010, the study regarding illicit drugs in 2015, and the studies regarding alcohol use between 1973 and 2017. Two studies, conducted in 1973 and 1975, focused mainly on the positive health outcomes of drinking alcohol for residents living in RCFs. In the period from 1994 until 2017, this focus shifted towards the prevalence and possible negative health outcomes of drinking alcohol for residents.

Table 3. Summary results for tobacco use

Notes: MMAT: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. RCF: residential care facilities. USA: United States of America. 1. 2.

a Study design based on the MMAT guideline

b This score consists of the total “yes” responses for each study

Table 4. Summary results for alcohol and illicit drug use

Notes: AUD: alcohol use disorder. MMAT: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. RCF: residential care facilities. USA: United States of America. 1. 2.

a Study design based on the MMAT guideline

b This score consists of the total “yes” responses for each study

Quality assessment

As described in the Methods section, the methodological quality was assessed using the MMAT, with a maximum score of 5 for each study design. The quality assessment identified ten studies with scores of 3 or more and six studies with scores of 2 or less (Tables 3 and 4). These six studies have a score of less than 50 per cent of the total score. However, no studies are excluded from this dataset, due to the limited dataset. The scores are merely used to indicate the current quality of research in this field.

General findings

This section provides an overview of the overall findings and is followed by two sections elaborating the main results regarding tobacco and alcohol use.

First, six of the included papers show the role of care professionals in observing, facilitating or regulating the alcohol and tobacco use of residents (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Carosella et al., Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002; Klein and Jess, Reference Klein and Jess2002; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Carosella, Podgorski and Ossip-Klein2004; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017). For example, Barker and Lewis (Reference Barker and Lewis1998) reported that care professionals decide when and how many cigarettes a resident is allowed to smoke per day. Moreover, Dreher-Weber et al. (Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017) found an underestimation of the prevalence of alcohol use by nursing staff compared to the hair analysis.

Second, the populations under study varied: three studies assessed the perspective of administrators, two the perspective of social workers, six the perspective of nursing staff and five the residents’ perspective. From these five studies, three studies assessed the residents’ perspective through interviews with residents themselves (Carosella et al., Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002; De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017) and two added observations to their data (Mishara et al., Reference Mishara, Kastenbaum, Baker and Patterson1975; Wolfsen et al., Reference Wolfsen, Barker and Mitteness2001). Two studies described their methods as assessing the residents’ perspective but did not present this perspective in their results (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998). Both studies stated that they did not include the residents’ perspective because the views of residents on smoking and smoking management were consistent with the staff's perspective (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998).

Third, studies assessing the use of alcohol and tobacco differed in focus and, therefore, are discussed separately in this paper. Studies regarding tobacco use balanced the right of residents to smoke with the regulation of smoking due to health and safety issues, whereas studies on alcohol focused more on the health of residents in relation to alcohol use. The study regarding illicit drug use describes issues regarding alcohol use and not further specified substance use. Therefore, this study was not assessed separately but discussed in the section regarding alcohol use.

Tobacco

Nine papers assessed tobacco use in residents living in RCFs (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994; Adler et al., Reference Adler, Greeman, Rickers and Kuskowski1997, Reference Adler, Greeman, Parker and Kuskowski2002; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Wolfsen et al., Reference Wolfsen, Barker and Mitteness2001; Carosella et al., Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Carosella, Podgorski and Ossip-Klein2004, Reference Watt, Lassiter, Boyle, Kulak and Ossip-Klein2009; De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010). Results of these studies showed that policies of RCFs state that residents have the right to smoke. However, facilities often regulate smoking, with safety as the most important reason, specifically a fear of fire (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994). The struggle to balance the possibilities to smoke with health and safety for all was reflected in three themes, which will be discussed here: prevalence, policies and the role of care professionals.

Prevalence

The results concerning the prevalence of tobacco use in residents show the importance of the possibilities to smoke and the low motivation of residents to quit smoking.

Four studies showed that the prevalence of smoking residents varied from 0 to 23 per cent (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Wolfsen et al., Reference Wolfsen, Barker and Mitteness2001; De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010). In three of these studies, the prevalence in tobacco use was based on estimates made by staff, such as care professionals or administrators, and the prevalence was estimated to be between 0 and 15 per cent (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Wolfsen et al., Reference Wolfsen, Barker and Mitteness2001). One study assessed the prevalence through information provided by nursing staff, and this was compared with information collected in interviews with the residents themselves, which resulted in an overall prevalence of 23 per cent (De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010).

The importance of smoking and the motivation to quit in the smoking residents was also assessed (Wolfsen et al., Reference Wolfsen, Barker and Mitteness2001; Carosella et al. Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002; De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010). According to Wolfsen et al. (Reference Wolfsen, Barker and Mitteness2001), being able to smoke when and where residents wanted maintained their feeling of autonomy. Moreover, Carosella et al. (Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002) found a low level of behavioural change in the smoking residents; 68 per cent of all smokers did not have the intention to quit within the next six months. De Carvalho et al. (Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010) presented similar results in which 57.7 per cent of the smoking residents showed a low level of behavioural change. The limited motivation to quit is reflected in the smoking status, which tends to remain similar after admission (Carosella et al., Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002; De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010).

Policies

The struggle to balance smoking possibilities with health and safety for all was reflected in a reported lack of overall comprehension of institutional policies (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Lassiter, Boyle, Kulak and Ossip-Klein2009). For example, according to Barker et al. (Reference Barker, Mitteness and Wolfsen1994), each unit within the studied facility developed their own management strategies to comply with the institutional policy, partly depending on the degree of tolerance by staff to smoking in general. These strategies varied from designated areas in which residents are allowed to smoke to not offering cigarettes to residents with dementia because nursing staff stated that these residents will forget that they smoked and, therefore, will stop asking to smoke. In addition, Barker and Lewis (Reference Barker and Lewis1998) reported that administrators of the 15 included facilities approached smoking differently; residents’ smoking was seen as an integral part of care to enhance quality of life or smoking was seen as a costly practice keeping staff from primary care. These examples show that the implementation of the institutional policies by care professionals differed per unit, which affect the possibilities of residents smoking.

Care professionals

The included studies show a role of care professionals in the regulation of smoking by residents living in RCFs (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Greeman, Rickers and Kuskowski1997; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Carosella, Podgorski and Ossip-Klein2004). This role could be affected by the attitudes of care professionals and, moreover, was reflected in the implementation of policies and conflicts between residents and staff (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Greeman, Rickers and Kuskowski1997; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998). Barker and Lewis (Reference Barker and Lewis1998) found that a variety of practices were reported to control smoking, such as controlling smoking opportunities and materials; 60 per cent of the facilities kept the smoking materials of smoking residents who are classified as ‘unsafe smokers’ and this label was rarely reviewed or reversed.

Three studies described attitudes of administrators and care professionals regarding smoking that affected the way care professionals act towards smoking residents (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Greeman, Rickers and Kuskowski1997; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Carosella, Podgorski and Ossip-Klein2004). For example, Barker and Lewis (Reference Barker and Lewis1998) found that 89 per cent of the administrators viewed smoking as an addiction and 72 per cent as a dirty habit. Administrators did not see assisting residents with smoking as a primary duty for care-giving staff. Of the 19 administrators who participated in their study, 21 per cent currently smoked, 42 per cent were former smokers and 37 per cent never smoked. According to Watt et al. (Reference Watt, Carosella, Podgorski and Ossip-Klein2004), the health beliefs of staff were not predictive of providing smoking cessation advice and, moreover, they found two experienced barriers to offering advice: an expected low level of motivation to quit in residents and institutional policies that allow residents to smoke.

Adler et al. (Reference Adler, Greeman, Rickers and Kuskowski1997) showed that significantly greater conflicts arose regarding smoking between residents and staff in facilities permitting smoking (61%) compared to smoke-free facilities (31%). The most important reasons for these conflicts were a lack of adequate and appropriate space, the amount of time staff spend facilitating smoking, and issues of health and personal safety.

Alcohol

Six of the included papers studied alcohol use in residents living in RCFs (Chien et al., Reference Chien, Stotsky and Cole1973; Mishara et al., Reference Mishara, Kastenbaum, Baker and Patterson1975; Weyerer et al., Reference Weyerer, Schäufele and Zimber1999; Klein and Jess, Reference Klein and Jess2002; Brennan, Reference Brennan2005; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017) and one paper also assessed illicit drug use (White et al., Reference White, Duncan, Burr Bradley, Nicholson, Bonaguro and Abrahamson2015). Most papers regarding alcohol use focused on the health of residents living in RCFs. The studies conducted in 1973 and 1975 mainly observed improvement in functioning, increased communication and socialisation in residents (Chien et al., Reference Chien, Stotsky and Cole1973; Mishara et al., Reference Mishara, Kastenbaum, Baker and Patterson1975). Studies conducted between 1994 and 2017 mostly assessed the negative effects of alcohol on mental and physical health (Weyerer et al., Reference Weyerer, Schäufele and Zimber1999; Klein and Jess, Reference Klein and Jess2002; Brennan, Reference Brennan2005; White et al., Reference White, Duncan, Burr Bradley, Nicholson, Bonaguro and Abrahamson2015). For example, Brennan (Reference Brennan2005) studied alcohol use disorders (AUDs) in residents and found that residents with an AUD required more mental health and social services. AUDs were categorised as alcohol psychosis (20%), alcohol dependency (55%), alcohol abuse or alcoholism (24%), and alcoholic liver disease or other alcohol-related disorders (1%) according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 9, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). In their results, residents with AUDs were studied as one group and compared with residents without AUDs. However, the studies of Dreher-Weber et al. (Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017) and Weyerer et al. (Reference Weyerer, Schäufele and Zimber1999) show a prevalence of problematic alcohol use in residents living in RCFs, 11.3 and 3.4 per cent, respectively, which means that the focus on negative health effects specifically in residents with AUDs is a small group compared to the total population of residents living in RCFs. The focus on health was also reflected in prevalence, policies and the role of care professionals.

Prevalence

As mentioned above, two studies assessed the prevalence of alcohol misuse in residents (Weyerer et al., Reference Weyerer, Schäufele and Zimber1999; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017). Dreher-Weber et al. (Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017) identified 11.3 per cent of the residents as hazardous drinkers – those who drank above the recommended limit of less than one alcoholic unit per day (10–14 grams of alcohol per day). They also found that nursing staff underestimated the prevalence of alcohol use in residents by comparing a hair analysis with the nursing staff's estimations. Nursing staff reported abstinence in 31 per cent of the residents who drank regularly but not excessively and in 40 per cent of the residents who were chronic-excessive drinkers, as indicated by a hair analysis (Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017). Moreover, Weyerer et al. (Reference Weyerer, Schäufele and Zimber1999) reported that 3.4 per cent of the residents abused alcohol once or on several occasions in the previous four weeks. Alcohol consumption was estimated by staff and rated as ‘none’, ‘moderate’ or ‘abusive’. Alcohol abuse was rated when residents met the criteria of alcohol abuse of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10 (ICD-10) and moderate alcohol use was rated when residents did not meet these criteria. Weyerer et al. (Reference Weyerer, Schäufele and Zimber1999) also assessed the negative health outcomes in residents, specifically a health risk related to older adults. Their study reported a significantly increased risk of falling in residents with alcohol-related problems.

To assess the prevalence and the negative health outcomes of alcohol use, screening instruments were studied in two papers (White et al., Reference White, Duncan, Burr Bradley, Nicholson, Bonaguro and Abrahamson2015; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017). White et al. (Reference White, Duncan, Burr Bradley, Nicholson, Bonaguro and Abrahamson2015) reported that 40 per cent of the included facilities used screening instruments, such as the CAGE or AUDIT-M, to assess substance misuse. Dreher-Weber et al. (Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017) assessed the validity of a screening instrument, the AUDIT-C, compared to an objective biomarker (hair analysis). These screening instruments are used to identify alcohol use in residents objectively.

Policies

In contrast to studies assessing tobacco use in RCFs, only one study regarding alcohol use assessed policies towards alcohol use. The study of Klein and Jess (Reference Klein and Jess2002) focused on the prevention of negative health outcomes in residents and, therefore, assessed the policies to regulate alcohol use in 111 facilities. This study showed a variety of policies concerning alcohol use in residents, exemplified by providing regular cocktail hours (26.4%), requiring doctors’ permission to drink alcohol (58.6%) or not allowing alcohol use in the facility for residents (36.9%). Multiple policies were reported, even within the same facilities. Three out of the 111 facilities denied the admission of any applicant with a history of alcohol problems. Moreover, 83.8 per cent of the facilities reported some problems arising from alcohol use, such as falls or social and behavioural problems.

Care professionals

In one study assessing alcohol use, the role of care professionals was reflected in the management of policies (Klein and Jess, Reference Klein and Jess2002). Klein and Jess (Reference Klein and Jess2002) described that not all staff members followed the rules or policies of their facility regarding alcohol consumption and 55.8 per cent of the 111 facilities felt it was appropriate or very appropriate for older residents to have access to alcoholic drinks. Their study also found that 86.5 per cent of the facilities believe that problematic alcohol use is a disease. It was not further elaborated as to when care professionals defined alcohol use as problematic. These results show that care professionals regulate the alcohol use in residents and demonstrate an ambiguity in the definitions of appropriate alcohol use and problematic alcohol use by care professionals.

Discussion

This scoping review was conducted to provide an overview of the published research in substance use and misuse among older adults living in RCFs and to identify what is important to study in future research to enhance PCC, especially in cases in which residents wish to choose unhealthy behaviours. The results of this review show that the current field of research mainly focused on alcohol and tobacco instead of other non-prescribed drugs. Moreover, the results show that care professionals have an important role in facilitating or regulating substance use and misuse. Finally, the number of studies conducted from the residents’ perspective are limited.

Studies regarding tobacco use showed that the view on smoking in general changed over time. The current older population living in RCFs started smoking when smoking was highly prevalent in all age groups and before the adverse health outcomes were well-known (Elhassan and Chow, Reference Elhassan and Chow2007; Lester and Kohen, Reference Lester and Kohen2008). Moreover, it was found that the motivation in residents to quit smoking is low (Carosella et al., Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002; De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010). Most studies regarding tobacco use were conducted between 1994 and 2010, the period in which the focus on the residents’ perspective increased and the focus of care in general shifted towards PCC (Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018). However, when residents have a low motivation to quit smoking and limited knowledge of the adverse health outcomes, it challenges care professionals to implement PCC. The needs and values of residents in these cases may be opposite to the values of care professionals themselves which may affect the implementation of PCC in practice. Therefore, PCC in these cases requires a supportive organisational culture and knowledge of the beliefs of care professionals themselves to solve these emerging challenges. Amongst others, these aspects are prerequisites of implementing PCC in practice, according to McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2006). The view on alcohol in general also evolved over time. Studies regarding alcohol use and misuse increasingly focused on the prevention of negative health outcomes. This is reflected in the studies regarding alcohol use in residents living in RCFs: studies published in 1973 and 1975 focused on the positive health outcomes of alcohol and the studies published between 1999 and 2017 focused on the negative health outcomes. This evolved view means that the current older population living in RCFs may not be aware of the adverse outcomes of substance use and misuse and, therefore, are not motivated to change. In addition, the current older population living in RCFs may experience alcohol use as beneficial, because it enhances their social participation (Iparraguirre, Reference Iparraguirre2015; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Olanrewaju, Cowan, Brayne and Lafortune2018). This may increase their self-rated health and wellbeing, despite their mental and physical impairments, which enhances successful ageing. The concept of successful ageing has a variety of definitions, but was consistently related to a younger age, non-smoking, higher physical activity, better self-rated health and no cognitive impairments (Depp and Jeste, Reference Depp and Jeste2006). However, the frail residents living in RCFs do not meet these criteria. Wahl et al. (Reference Wahl, Deeg and Litwin2016) suggested that the concept of successful ageing should be reconsidered in the presence of physical or mental impairments. With this broader definition, it could complement PCC by considering how residents living in RCFs age successfully in the light of their self-rated health and wellbeing.

Overall, care professionals are challenged to implement PCC, because it requires interpersonal and communication skills of care professionals to have a dialogue with the residents to assess their needs and values, their motivation to change, inform them of the currently known adverse outcomes and the consequences of their choices.

This review also showed an ambiguity for care professionals in the distinction between alcohol use and misuse in residents (Klein and Jess, Reference Klein and Jess2002). Consensus of this distinction is essential to determine whether residents use or misuse alcohol. The results of this review show only a small group of residents living in RCFs who misuse alcohol (Weyerer et al., Reference Weyerer, Schäufele and Zimber1999; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017). Residents who misuse alcohol require a different approach with regard to PCC, exemplified in the protection of these residents by care professionals to help them overcome their misuse and, in this way, act in their best interest. Therefore, this distinction is important to know because it determines how PCC is implemented.

To enhance PCC in substance use and misuse, the role of care professionals was found to be of great importance. The findings of this review show that care professionals decide to facilitate or regulate alcohol and tobacco use (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Greeman, Rickers and Kuskowski1997; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Klein and Jess, Reference Klein and Jess2002; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Carosella, Podgorski and Ossip-Klein2004; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017), which is exemplified in the implementation or the lack of implementation of policies by care professionals (Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998). The attitudes of care professionals towards alcohol and tobacco may affect their decision to facilitate or regulate alcohol and tobacco use in residents. In addition, not all care professionals follow the policies of their facility (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Greeman, Rickers and Kuskowski1997; Barker and Lewis, Reference Barker and Lewis1998; Klein and Jess, Reference Klein and Jess2002; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Carosella, Podgorski and Ossip-Klein2004). Therefore, this review shows a gap between organisational policies and the implementation of these policies by care professionals, possibly due to their own values. The values and attitudes of care professionals towards substance use and misuse may affect the dialogue with residents to assess their needs and values and inform them of the consequences of their choices. This may in turn affect implementing organisational policies regarding substance use and misuse.

In this review, only five studies assessed the perspective of residents (Mishara et al., Reference Mishara, Kastenbaum, Baker and Patterson1975; Wolfsen et al., Reference Wolfsen, Barker and Mitteness2001; Carosella et al., Reference Carosella, Ossip-Klein, Watt and Podgorski2002; De Carvalho et al., Reference De Carvalho, Gomes and Loureiro2010; Dreher-Weber et al., Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017). The other studies were conducted from the perspective of administrators, social workers or nursing staff. There are a limited number of studies assessing the residents’ perspective in the current field of research regarding older adults living in RCFs in general. For example, Donnelly and MacEntee (Reference Donnelly and MacEntee2016) reported limited knowledge on how residents living in RCFs feel about the quality of care and their own quality of life. In addition, Roelofs et al. (Reference Roelofs, Luijkx and Embregts2015) reported that the residents’ perspective was lacking in studies regarding personal matters such as intimacy and sexuality. The limited number of studies assessing the residents’ perspective could be explained due to the physical and cognitive impairments in older adults living in RCFs (Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018), which creates practical and ethical issues when including their perspective in scientific research. However, to enhance PCC, not only in practice but also in research, the residents’ perspective is essential.

Overall, this scoping review highlights that the focus on studies regarding substance use and misuse in residents living in RCFs is consistent with the views on substances in the general population: an increased knowledge of negative health outcomes and, therefore, an increased focus on the prevention of negative health outcomes. However, the shift towards PCC in RCFs increased the focus on residents’ needs and values (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2018). This model of care involves residents by offering them choices and shared decision making to maximise each individual's potential (Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Winblad and Sandman2008; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2018). Therefore, challenges emerge when implementing PCC in RCFs. This review shows that to enhance PCC in RCFs regarding substance use and misuse it is important to understand the distinction between substance use and misuse, to focus on the residents’ perspective, and to assess the knowledge and attitudes of residents and care professionals towards substance use and misuse. This distinction and these perspectives should be considered when implementing policies regarding substances and incorporate these policies in organisational cultures.

Strengths and limitations

A complete and broad review of the current field of research was provided, as all substances were included in this scoping review. This showed that the focus in this field of research is on alcohol and tobacco instead of other non-prescribed drugs. The methodological quality of the included studies appeared to be variable. The methodological quality of some studies was scored to be low. The studies with a lower-scored methodological quality were interpreted with more caution.

The results of this review show possible underreporting of substance use and misuse which could bias the true prevalence of substance use and misuse in the older adults living in RCFs as reported in this review. Dreher-Weber et al. (Reference Dreher-Weber, Laireiter, Kühberger, Kunz, Yegles, Binz, Rumpf, Hoffman, Praxenthaler and Wurst2017) found an underestimation by care professionals of the prevalence of alcohol use in residents. Other studies reported that the underreporting could be explained due to the instruments used to assess substance use and misuse, a lack of relevant drinking guidelines and increased contents of alcoholic drinks, such as a glass of wine, which may bias the actual alcohol use (Greenfield and Kerr, Reference Greenfield and Kerr2008; Lovatt et al., Reference Lovatt, Eadie, Meier, Li, Bauld, Hastings and Holmes2015; Britton et al., Reference Britton, O'Neill and Bell2016).

This review focused on substance use and misuse in RCFs specifically. The nature of RCFs varied and the definitions of RCFs were ambiguous in some of the papers included in the selection process. Therefore, the inclusion process with regard to equality of the studied facilities was challenging. However, this focus on RCFs contributes to an increased awareness of the practical and ethical issues involved in substance use and misuse in residents, and this review could be part of a foundation for future research to address these issues by comparing the outcomes of this review with empirical research.

Implications for future research

Future research should incorporate the perspectives of residents, care professionals and the organisation to enhance PCC and enable residents to make shared and well-informed decisions in dialogue with care professionals. There is a need for well-considered and well-founded ethical decisions by care professionals (Bolmsjö et al., Reference Bolmsjö, Edberg and Sandman2006), especially regarding regulating or facilitating substance use in residents living in RCFs. This may enhance providing PCC because a careful consideration of individual interests is necessary to assess the needs and values of residents and the limiting factors and possible consequences for themselves and the environment involved. Moreover, future research should assess the distinction between substance use and misuse and how this affects providing PCC in RCFs. The role of care professionals emphasised the dependency of residents on their care-givers to fulfil their needs and incorporate their values. This could be relevant in other care issues where the aim is to provide PCC. Therefore, future research should incorporate the challenges emerging from this review involved in implementing PCC in RCFs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001215.

Author contributions

LG conducted the literature search and selection, assessed the quality of the selected articles, extracted data and constructed the tables. MJ and TR selected the articles, assessed the quality of the selected articles and extracted data. All the authors, including KL, interpreted the findings and were involved in the drafting and revisions of the manuscript. All authors approved the publication of the article.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.