Introduction

Background

For organisations, the timing of retirement is coming into question as a result of the increasing proportion of older workers in many countries. One reason that this is important for organisations is that some of these employees are healthy, willing and able to continue working beyond traditional retirement age, while others are not (Sargent et al., Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2012; Baruch et al., Reference Baruch, Sayce and Gregoriou2014; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Chaffee and Sonnega2016; Lain et al., Reference Lain, Airey, Loretto and Vickerstaff2019). This situation leads to the risk of losing skilled and experienced workers and a general shortage of labour caused by the large numbers of retirements in many organisations (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2017). The issue of ageing populations and older workers is also a topic for recent organisational research, as it has been termed one of the most significant socio-economic challenges currently facing the OECD and the European Union (EU) (Kulik et al., Reference Kulik, Ryan, Harper and George2014; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Hardy, Cutcher and Ainsworth2014; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Philipson2016). However, there is still a call for more research on both the impact of retirement inside organisations (Kulik et al., Reference Kulik, Ryan, Harper and George2014, Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Philipson2016) and the role of organisations in ‘reifying age as a system of classification with significant effects’ through decisions on when older workers are retired (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Hardy, Cutcher and Ainsworth2014: 1570).

Many earlier studies have investigated the role of the social insurance system and the direct impact on the individual, or vice versa (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Philipson2016). The direct relationship between the societal and individual level are thus highlighted. One reason why more studies are called for is that in this body of literature, analysis and theories of the role of organisations and employers are relatively scarce, despite the fact that organisations are important social actors and constitute a separate level of analysis for understanding the complex social processes that determine the timing of retirement (Brooke et al., Reference Brooke, Taylor, McLoughlin and Di Biase2013; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Guest, Clinton, Knight, Jansen and Dikkers2013; van Dalen et al., Reference van Dalen, Henkens and Wang2015; Kulik et al., Reference Kulik, Perera and Cregan2016). Here, we will show the particular usefulness of the theoretical concept of co-existing ‘narratives’ at the societal (i.e. ‘meta’-narratives), organisational and individual levels. The co-existence of narratives sometimes involves the creation of counteracting so-called ‘ante-narratives’ (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2004). Narratives are useful to understand because they are tools and arenas for negotiating social action that provide justifications and value judgements on legitimate actions as well as selecting who the central actors are (Fiol, Reference Fiol1989; Zilber, Reference Zilber, Mir and Jain2017). We will show why and how it is insufficient to select only policy makers and individuals as the central actors in research narratives about retirement timing.

Previous studies at the individual level of analysis have shown that older workers are subjected to a taken-for-granted societal narrative of ‘age as decline’ (Trethewey, Reference Trethewey2001; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Guest, Clinton, Knight, Jansen and Dikkers2013; Kulik et al., Reference Kulik, Perera and Cregan2016). Age is associated with a declining body, which in turn is considered by employers, managers, human resources (HR) and younger colleagues to be correlated with a decline in productivity (Brooke et al., Reference Brooke, Taylor, McLoughlin and Di Biase2013). For this reason, one study showed how the vampire metaphor is befitting many organisations and employers in the sense that norms of a constant need for ‘fresh blood’ are perpetuated (Riach and Kelly, Reference Riach and Kelly2015). The timing of retirement seen from this perspective is mainly depicted as ‘the earlier the better’, because through retiring older workers the employer gains resources to employ the new and more up-to-date generation (Pritchard and Whiting, Reference Pritchard and Whiting2014). At the same time, retirement has also often been seen as offering freedom to the individual (Sargent et al., Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2012; Bengtsson and Flisbäck, Reference Bengtsson and Flisbäck2017).

However, a countering ante-narrative of active and productive ageing has become dominant in the policy debate at the societal level of analysis – including a push for ‘prolonging of working life’, i.e. delayed retirement (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Philipson2016). In such discussions, policy makers often put forward the business case for a prolonged working life (LaLiberte Rudman and Molke, Reference LaLiberte Rudman and Molke2009; Flynn, Reference Flynn2010; Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2015; Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016). Within the EU, where Sweden is a Member State, there is political agreement that the increase in the ‘demographic dependency ratio’ should be addressed: EU citizens are encouraged to work more years in order to help sustain the welfare systems (Kadefors et al., Reference Kadefors, Wikström and Arman2020). For this reason, individuals, and sometimes employers, are encouraged by governments to prolong working life through incentives and changes in regulations, as well as in response to the wishes of individual employees (Flynn, Reference Flynn2010). Consequently, across the EU and in Sweden statistics show that since 2002 work participation among 55–64 year olds has slowly increased (Eurostat, 2020).

At the same time, in some EU countries, including Sweden, collective agreements between social partners set important parameters on working-life exit-frameworks (Gruber and Wise, Reference Gruber and Wise1998; König et al., Reference König, Hess, Hofäcker, Hofäcker, Hess and König2016). Through such agreements and other organisational-level measures, employers may well apply a downsizing or ‘skills shift’Footnote 1 policy to encourage employees to exit prematurely. Employers accomplish a shift from old employees to new ones by providing attractive employment pension benefits already at age 60, for example – ‘an offer that cannot be refused’. Thus, the two narratives of reasons for early versus delayed retirement, respectively, co-exist among organisational actors. Since the workplace is an important social arena for decisions regarding retirement (Sargent et al., Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2012), the question remains how these counteracting narratives of older workers as either a problem or a solution, are linked, maintained and possibly changed inside organisations. It is against this background that our case study will show how organisational actors in Sweden are taking part in the institutional work of maintaining retirement-timing narratives and also how other existing organisational narratives are used to disrupt narratives of prolonging working lives.

Previous studies of organisations and older workers

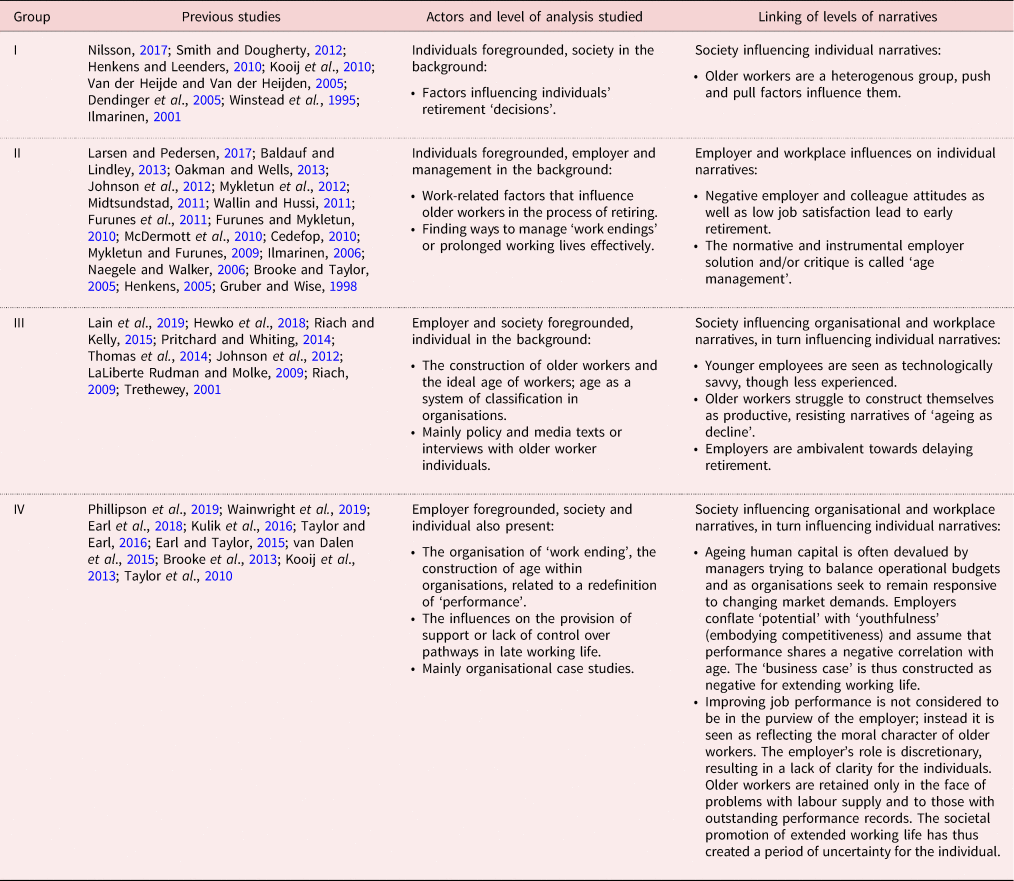

This section presents a selection of previous studies investigating ageing workers and changes in views on appropriate retirement timing in the context of the ageing workforce. In order to tease out research gaps in this multifaceted body of literature, we have grouped the studies by what we have interpreted to be the main actors and levels of analysis studied, as well as the links observed between the levels of analysis. These links are what in this study we will refer to as part of the institutional work of maintaining and/or changing the narratives that guide action regarding retirement timing. Table 1 summarises this overview of the studies we selected as influential in the area of our study, which we wish to contribute to. The theory of institutional work and how it is related to narrative analysis will be presented in the next section.

Table 1. Previous studies grouped by main actors and level of analysis, as well as the types of link found between levels of narratives

In the first group of the selected previous studies (Group I; see Table 1), the older individuals were placed in the foreground, against the (often taken for granted) background of the changing context of demographics and of policies to prolong working lives. The factors influencing the decisions of the older workers on when to retire are subject to investigation in this group, which almost exclusively focuses on the individual and looks at specific factors (Hewko et al., Reference Hewko, Reay, Estabrooks and Cummings2018). The factors considered include the employability of older workers (Van der Heijde and Van der Heijden, Reference Van der Heijde and Van der Heijden2005), their perceived health (Ilmarinen, Reference Ilmarinen2001; Henkens and Leenders, Reference Henkens and Leenders2010), their social situation (Winstead et al., Reference Winstead, Derlega, Montgomery and Pilkington1995), and their attitudes to work and retirement (Dendinger et al., Reference Dendinger, Adams and Jacobson2005; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2010; Smith and Dougherty, Reference Smith and Dougherty2012). One way to illustrate the factors related to the individual is by classifying them into four categories, along two dimensions: (a) those who can and want to continue working; (b) those who can but do not want to; (c) those who cannot but want to; and (d) those who cannot and do not want to (Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017; Kadefors, Reference Kadefors, Wikström and Arman2020). We summarise the contribution of this group of studies by concluding that older workers are a heterogeneous group, as this categorisation shows (see also LaLiberte Rudman and Molke, Reference LaLiberte Rudman and Molke2009). However, the role of the organisation in co-creating a situation of ‘can or cannot’ as well as ‘want to or do not want to’ is under-problematised in the studies focusing on the individual's traits or behaviour.

In the second group of selected previous studies (Group II; see Table 1), research has shown that there are not only factors related to the individual but also work-related ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors influencing premature retirement (Hewko et al., Reference Hewko, Reay, Estabrooks and Cummings2018). The selected previous studies of work factors have shown that early retirement is related to low job satisfaction (Oakman and Wells, Reference Oakman and Wells2013), age discrimination at work (Riach, Reference Riach2009; Furunes and Mykletun, Reference Furunes and Mykletun2010; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Billett, Dymock and Martin2012), and negative attitudes among managers and colleagues (Gruber and Wise, Reference Gruber and Wise1998; Brooke and Taylor, Reference Brooke and Taylor2005; Henkens, Reference Henkens2005; Mykletun et al., Reference Mykletun, Furunes and Solem2012). Although these studies contribute to the understanding of specific employer-related organisational factors in the timing of retirement, the context-dependent, co-created, meaning-making organisational processes behind these factors are difficult to discern. As Philipson et al. phrase it:

Extended working life is presented as widening options but it leaves unresolved for many older workers their role and status within employment. Understanding the complex ways in which ‘age’ is constructed and managed within the workplace should become a major topic of interest in social policy research on the changing transitions from work to retirement. (Philipson et al., Reference Phillipson, Shepherd, Robinson and Vickerstaff2019: 348)

Moreover, this second group of previous studies imply a need for organisational changes and a departure from retirement being constructed as merely the individual's choice. Neither is it merely forced by factors related to the individual, such as the view that ageing is a process of decline which makes the person unfit for work (Sargent et al., Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2012). In this group of studies, the term ‘age management’ has emerged as a way to describe organisational activities aimed at promoting a longer working life and/or at balancing the needs of different age groups in an organisation (Brooke and Taylor, Reference Brooke and Taylor2005; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Kazi, Munir and Haslam2010; Furunes et al., Reference Furunes, Mykletun and Solem2011; Baldauf and Lindley, Reference Baldauf and Lindley2013). An authority in the area, Ilmarinen (Reference Ilmarinen2006: 120) defines age management as ‘taking the employee's age and age related factors into account in daily work management, work planning and work organization’. Based on 200 case descriptions of organisations’ age management practices,Footnote 2 Naegele and Walker (Reference Naegele and Walker2006) reported that age management initiatives taken in organisations reflected a spectrum of underlying business needs such as maintaining the skills base, reducing age-related labour costs and resolving labour market bottlenecks. Another study showed how European employers sort workers upward or outward (early exits), depending on several different organisational context factors (van Dalen et al., Reference van Dalen, Henkens and Wang2015).

As an important contribution from these studies, we view age management practices as part of an organisational narrative where older workers might be portrayed by employers and colleagues as a solution to productivity problems (see e.g. Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Greller and Stroh2002; Mykletun and Furunes, Reference Mykletun, Furunes and Kumashiro2009; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Hardy, Cutcher and Ainsworth2014). Seen from the employer's perspective, a pure business or efficiency perspective on retirement is possible, or this can be complemented by and mixed with a legitimacy perspective and normative values concerning what is socially responsible for an organisation to do (see also Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016). Examples of the latter include issues of age as part of diversity management and efforts to counter age discrimination (Cedefop, 2010; Midtsundstad, Reference Midtsundstad2011; Wallin and Hussi, Reference Wallin and Hussi2011; Baldauf and Lindley, Reference Baldauf and Lindley2013; Larsen and Pedersen, Reference Larsen and Pedersen2017). Yet studies so far show few examples of employers being explicitly active in deploying strategies or projects regarding age management, delaying retirement, or dealing with age discrimination and norms (Sargent et al., Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2012; Kulik et al., Reference Kulik, Perera and Cregan2016; van Dalen et al., Reference van Dalen, Henkens and Wang2015). This may be attributable to the fact that employers only recently have started to face more severe problems with recruitment of skilled personnel to replace older workers as they retire (Baruch et al., Reference Baruch, Sayce and Gregoriou2014; van Dalen et al., Reference van Dalen, Henkens and Wang2015).

In the third group of selected previous studies (Group III; see Table 1), a few researchers have gone on to explore the specific discursive construction of older workers, which contributes to factors such as negative attitudes towards ageing and low job satisfaction. These studies have shown that younger employees are constructed as more dynamic and technologically savvy, although some work experience is still required and valued (Pritchard and Whiting, Reference Pritchard and Whiting2014). Organisational researchers note that norms of the ideal worker relate strongly to a narrow age group, and stereotypes related to age benefit some while others lose out, depending on nothing else besides the number of years they have lived: ‘Images of age saturate organizational processes, working to privilege some organizational members while marginalizing those who transgress age norms’ (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Hardy, Cutcher and Ainsworth2014: 1571). Older workers themselves have also been found to take part in reproducing this narrative of self-management and discipline, resisting their own ageing, in order to fit the organisational ideals (Trethewey, Reference Trethewey2001).

Thus, organisational research so far has mainly shown that the societal discourse on older workers dovetails with the increase in neo-liberalist policies, placing the responsibility for maintaining productivity and activity squarely on the individual. These types of norms and ideologies hide the responsibility of employers and link together the policy-level and individual-level narratives, often still skipping over the organisational level (see LaLiberte Rudman and Molke, Reference LaLiberte Rudman and Molke2009; Riach, Reference Riach2009; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Billett, Dymock and Martin2012). For this reason, studies investigating the meaning-making and narratives of retirement among older individuals as well as among the general public or in policy debate (e.g. analysing interviews, media or policy texts) construct a meta-narrative where employers are ‘passive actors’.

In the fourth group of selected previous studies (Group IV; see Table 1), a few scholars have investigated discourses at the policy and societal level directed at the employer, e.g. promoting a business case rationale for delaying retirement (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Billett, Dymock and Martin2012; Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016). Also, these studies have gone on to conduct case studies of the organisational-level processes that form actions that either maintain negative stereotypes and early exits or change the narratives towards continued development, wellbeing, inclusion and prolonged working lives for older workers (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Brooke, McLoughlin and Di Biase2010; Brooke et al., Reference Brooke, Taylor, McLoughlin and Di Biase2013; Earl and Taylor, Reference Earl and Taylor2015; Earl et al., Reference Earl, Taylor and Cannizzo2018). For example, the studies have analysed how organisations in some contexts pit the interests of older workers against those of the younger ones. In order to employ new, younger workers, the older ones must retire, according to this assumption of competing interests (Riach and Kelly, Reference Riach and Kelly2015). Also, studies of employers’ sense making of retirement timing often show their ambivalence about the desirability and feasibility of delaying retirement. The pressures and values of ‘flexibility’ and keeping up with changing market contexts collide with the values of experience that are coupled with older workers (Brooke et al., Reference Brooke, Taylor, McLoughlin and Di Biase2013; Earl and Taylor, Reference Earl and Taylor2015; Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Crawford, Loretto, Phillipson, Robinson, Shepherd, Vickerstaff and Weyman2019). The role and agency of HR within organisations is also related to an observed lack of employer responsibility for the process of engaging and keeping older workers’ skills up to date (van Dalen et al., Reference van Dalen, Henkens and Wang2015).

The aim of the current study is to analyse the institutional work involved in organisational actors’ narratives about older workers and retirement timing, against a background of society- and individual-level narratives. In our efforts, we join a stream of studies showing a (renewed) interest in specific ‘cultural’ aspects of institutionalisation: particularly the meaning that actors bring to and associate with the actions that constitute recurring organisational practices (e.g. Zilber, Reference Zilber2002, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009; Haack et al., Reference Haack, Schoeneborn and Wickert2012; Landau et al., Reference Landau, Drori and Terjesen2014). These studies argue that there is a need to return attention to the creation and micro-foundations of the very taken-for-grantedness that is the hallmark of institutionalisation (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2008, Reference Zilber, Mir and Jain2017). Our literature review shows that employer responsibility for retirement timing is one of these institutionalised processes in which organisations have an active role in creating the narrative micro-foundations.

Organisational narratives and institutional work

We propose that a narrative analysis can uncover the dynamics of the translation (i.e. linking) of and/or decoupling between meanings at different levels/arenas in society when it comes to retirement timing. Combined with an institutional work framework, such an analysis can develop our understanding of the maintenance and changes in patterns of meanings that inform the actions (Lawrence and Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006) – in our case, the institution of social insurance, specifically in the form of retirement. Institutions have been defined as ‘more or less taken-for-granted repetitive social behavior that is underpinned by normative systems and cognitive understandings that give meaning to social exchange and thus enable self-reproducing social order’ (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin, Suddaby, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2008: 4–5, emphasis added). As can be seen from this definition, the concept of institution is used to describe and analyse not only the everyday practices and actions of individuals and collective actors, but also the higher-order social systems – meta-narratives – that infuse these practices with meaning (see also Friedland and Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991).

Within this field, Lawrence and colleagues (Lawrence and Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Leca, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2011) have coined the term ‘institutional work’, defined as ‘the purposive actions carried out by individual and collective actors to create, maintain, and disrupt institutions’ (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2011: 52). Institutional work thus sheds light on the active and ongoing work done by various actors to uphold and transform institutions in various ways. This includes ‘work’ that is mundane and less visible, such as the creation, disruption and maintenance of meaning structures; the idea being that meaning structures influence actions and behaviours (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2008). One such meaning structure is that of narratives: the stories that we repeat in order to explain and communicate events. The patterns of meaning referred to here can be defined as recurring stories with a structure containing: ‘a narrative subject in search of an object, a destinator (an external force, the course of the subjects’ ideology), and a set of forces that either help or hinder the subject in acquiring the described object’ (Fiol, Reference Fiol1989: 279). Narratives about organisations, by presenting these elements, often serve the purpose of making sense of complex situations and turn them ‘into a simplified and relatively coherent portrait’ (Ashforth and Humphrey, Reference Ashforth and Humphrey1997: 53).

At the societal level, meta-narratives help make sense of and simplify the grand dilemmas shared by many. These narratives can be traced in local translations in different organisational arenas (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2004). Such narratives inherently help organisations to do symbolic work and gain legitimacy through the normative fit implied in the shared story: ‘Organizational elites translate [meta-narratives] into local – more specific and selective – versions, which are then used in organizational sense-making processes’ (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009: 207). In other words, a narrative contains good actors, struggling on route to an important end, and legitimacy is thus a central construction (Lounsbury and Glynn, Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001).

Examining narratives has previously proved useful for analysis in studies of institutional work and particularly institutional disruption and creation, since ‘during a change process, multiple narratives compete’ (Landau et al., Reference Landau, Drori and Terjesen2014: 1322). One question is recurrent in this literature: how different narratives co-exist in organisations, with related tensions and/or advantages of ‘multiplicity’ (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2008; Bartel and Garud, Reference Bartel and Garud2009; Landau et al., Reference Landau, Drori and Terjesen2014). The co-existence of multiple narratives in one organisational setting is described as a challenge or sign/cause of conflict as well as an opportunity to gain creative flexibility and legitimacy from multiple audiences and constituents (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Scully and Austin2002; Zilber, Reference Zilber2002, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009; Haack et al., Reference Haack, Schoeneborn and Wickert2012).

It is this kind of complexity and multiplicity of narratives that we expect to see when analysing employer narratives regarding retirement, since this part of the institution of social insurance is being questioned in society (LaLiberte Rudman and Molke, Reference LaLiberte Rudman and Molke2009; Baruch et al., Reference Baruch, Sayce and Gregoriou2014). Previous studies often argue that a multiplicity of narratives might be a necessity for institutional change to happen (Haack et al., Reference Haack, Schoeneborn and Wickert2012). For example, Zilber (Reference Zilber2002, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009) showed that the co-existence, and sometimes conflicting characteristics, of two meta-narratives inside one organisation caused tensions related to the different interests of the actors employing them. Consequently, over time specific HR practices such as recruitments changed. She concluded that institutional maintenance involved a successful adaptation of meta-narratives to local ‘then-specific’ organisational narratives, while institutional change instead demands ‘the radical transformation of an established meta-narrative’ (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009: 229, emphasis added).

Similarly, Landau et al. (Reference Landau, Drori and Terjesen2014: 1337) show how the very existence and active proposing of several different meta-narratives by actors in an organisation ‘expands the repertoire’ of the stories. In their longitudinal study, ultimately a narrative that reconciled the interests of the main actors came to dominate. The authors conclude that multiple narratives are developed in dialogue with, and in response to, each other:

The various narratives are a ‘meeting point’ in which different groups in the organization engage in dialogical interaction that must take into account the potential advantages and shortcomings of each other's narratives while defending their stance towards planned change. (Landau et al., Reference Landau, Drori and Terjesen2014: 1326)

To summarise our conceptual framework, we view co-existence and negotiation that leads to a specific ‘translation’ or ‘editing’, and thus the linking of narratives as a type of institutional work carried out by organisational actors. We follow a stream of earlier studies that have used narrative analysis in the study of institutional work, exploring the institutional maintenance, disruption and creation involved in translating and transforming meta-narratives in the arena of organisational actors. The meta-narratives of national stakeholders is what we view as ‘institutional’; they have been relatively stable when it comes to the social insurance and social security systems in Sweden, including retirement timing in the time period between the end of the Second World War and until quite recently (Sargent et al., Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2012). In our study, the research question is centred mainly on the relationships between the narratives of national-level society actors and narratives at the organisational level. In order to answer our research question, we will explore and analyse the national-level meta-narratives and organisational actors’ narratives in comparison to them.

Methods

Data collection and analysis

The study was carried out using three main sources of data: (a) documents, (b) meeting notes and (c) interviews with a network of HR experts from seven or eight organisations who met regularly over nearly four years in order to discuss ‘age management’ and retirement issues in their organisations and in general. In the document study, we mapped how stakeholders at the societal level (mainly the Swedish national arena) articulated their views with respect to the general issue of retirement and working-life exits. We studied and analysed policy documents issued by the Swedish government comparing narratives. In particular, we analysed documents relevant to the governmental Swedish Pension Age Commission of Inquiry formed in 2011; this included the Commission's terms of reference, its report and recommendations, as well as the responses to the recommendations voiced by the social partners. This analysis provided an understanding of the character of narratives on ageing and working-life exits that existed at the societal level at the time of the study (2015–2018).

The data collection from HR experts and for the organisational-level narratives began with the initiation of a research consortium – a group of practitioners from six to eight large organisations (three private companies and five public organisations) who met regularly three times per year. The aim of the meetings was knowledge exchange between companies and organisations that are working with issues of postponed retirement and an ageing workforce. Accordingly, the idea of the consortium was to create a basis for sharing experiences of age management among organisations and between organisations and the researchers. The participants in this part of the study thus represent the employer's perspective, close to the organisational ‘elite’ of management. No union or other employee representatives were present at the meetings.

The organisations which joined this research consortium and the regular 5–6-hour meetings represented large employers in Sweden and the three private-sector manufacturers were part of global multinational companies. They were manufacturers in the chemical and automotive industries. The public-sector organisations were three municipalities which in Sweden run elderly care, schools and social services, as well as everything to do with town planning and local infrastructure. One regional university hospital as well as the Swedish Prison and Corrections Authority were also represented. All of the organisations had 10,000 or more employees.

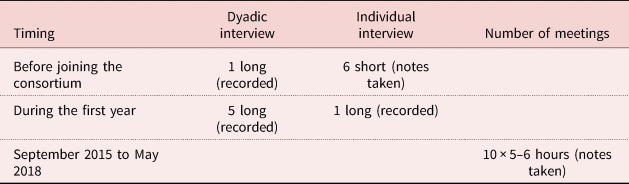

This paper is based on the analysis of detailed notes from discussions during these meetings and qualitative interviews with the participants. A short interview was conducted with six representatives before the consortium started meeting, at which only notes were taken. One long interview was conducted with an additional organisation before they joined, which was recorded. One year later, 1–1.5-hour semi-structured and recorded interviews were then conducted with representatives of six of the organisations. Some interviews were carried out with both representatives from the organisation at the same time (here called ‘dyadic interview’). See Table 2 for a summary of this data collection.

Table 2. The types of interviews and number of meetings with the consortium participants

The consortium started in September 2015 with representatives from six organisations. Some of the representatives changed during the subsequent years because they changed roles in their organisations. Also, one additional new organisation joined during the second year. The consortium held two meetings during the first year, then three meetings during 2016 and 2017, respectively, and finally two more meetings in 2018. The meetings were each approximately 5.5 hours long and notes were taken continuously by the researchers. We made note of the discussions and typed verbatim articulations mixed with summaries. The variation of themes of the discussions during meetings, mainly influenced by the participants’ interests, show a changing and multifaceted meaning framework for what is considered relevant to issues of prolonging working life and implementing age management. This includes discussions about occupational health, recruitment of talent, employer branding, promoting work motivation, job satisfaction, giving financial advice, legal restrictions and age discrimination.

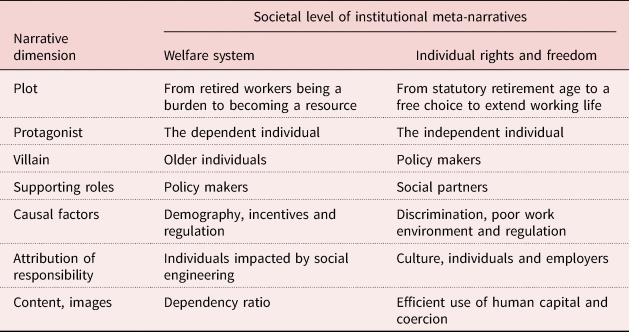

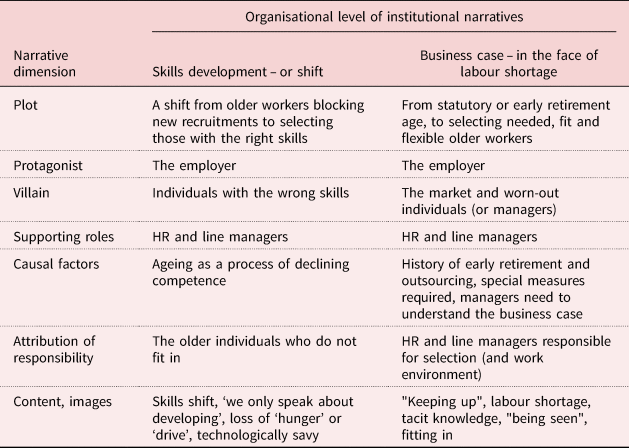

Qualitative content analysis was used to interpret the negotiation of organisational narratives in the meeting and interview materials, as well as in the collected documents. A narrative has a basic structure which includes recurring elements that are identifiable (Fiol, Reference Fiol1989; Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska2004). In the analysis, we identified articulations regarding older workers and retirement. We took inspiration from Zilber's (Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009) categories of narrative elements/dimensions and interpreted our material in the following categories: the basic Plot (the mission or social change being legitimised), Protagonist, Villain, Supporting roles, Causal factors (explaining the need for the plot and the hindrances), Attribution of responsibility and, finally, Content (recurring phrases or symbols, imagery, etc.). Through reading and re-reading the interviews and meeting notes, we interpreted recurring examples of two main national-level and two organisational-level narratives, respectively. The two national-level narratives were plots that related to sustaining the welfare system where older workers were sometimes portrayed as a resource and at other times a cost, and a plot that related to portraying retirement or the need for older workers as a human right and individual choice. The organisational narratives, on the one hand, had a plot concerning the need for a ‘skills transition’, where older workers blocked the recruitment of younger employees, and on the other, arguing the business case for carefully selecting some employees to keep in the face of a shortage in the labour market. These four narratives are presented further in the Findings section of the paper.

In our analysis we recognise that creating narratives involves work: ‘Narration involves the selection, combination, editing and molding of events into a story form … Further, stories are collective creations’ (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009: 208). It is, thus, more than just picking up ‘ready-to wear’ stories and making use of them (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Scully and Austin2002). Translation or editing is often part of the narrative work and social action that is done in organisations (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2008, Reference Zilber, Mir and Jain2017; Adorisio, Reference Adorisio2014). In conducting the analysis, we also acknowledged that the collective effort of creating and using narratives is political and part of attempts to further the actors’ interests, and thus is sometimes conflicting by nature (see e.g. Creed et al., Reference Creed, Scully and Austin2002; Zilber, Reference Zilber2002, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009; Haack et al., Reference Haack, Schoeneborn and Wickert2012).

Findings – editing organisational retirement narratives

Swedish retirement policy debate

We interpreted two main societal-level institutional meta-narratives in the studied Swedish policy process regarding retirement. The first is a narrative of welfare systems related to social democracy, where the plot is about how older workers need to go from being a burden to society to becoming a resource. The second meta-narrative is instead concerned with human values and rights related to neo-liberalism, and the plot is about going from a fixed statutory retirement age to the individual's freedom to choose when to retire (and to extend their working life). See Table 3 for a summary of the two co-existing national-level narratives.

Table 3. Narrating stories of retirement at the societal level

Note: Template following Zilber (Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009: 212).

In 2000, the EU launched the Lisbon Strategy which in part addressed the ‘insufficient participation in the labour market by women and older workers’. One of the targets for 2010 was a 50 per cent employment rate for workers aged 55 and above. In Sweden, work participation in 2017 among 55–64 year olds was 76.6 per cent (OECD, 2017); this places Sweden in the forefront among EU countries. Nevertheless, in Sweden too, the pension system is under scrutiny. The statutory retirement age, according to the OECD definition, has been unchanged since 1976. In 2011, the Swedish government launched a study aimed at pension system reform. In the terms of reference, it was noted that the number of people older than 65 years relative to those aged 20–64 would increase from 32 to 42 per cent over the next 20 years, increasing the so-called dependency ratio. The parliamentary study's recommendations, delivered in 2013, included a set of economic incentives and a right for employees to retain permanent employment until age 69 instead of the current 67. The basic rationales were coloured by economic and financial efficiency concerns, emphasising the individual's responsibility and need for stabilisation of the pension system.

However, employers were also addressed in general terms and asked to take measures against age discrimination, to strengthen opportunities for older workers to preserve and develop their skills, and to improve the work environment. In Sweden, the government may devise laws and regulations setting pension system frameworks, but labour market conditions are largely shaped by collective agreements between the social partners.Footnote 3 Both employer associations and trade unions agreed that conditions regulating working hours and employment pensions should be set by collective agreements also in the future, not be imposed by law, which can be seen as a defence of the Swedish system for labour market relations. Thus, in Sweden at the time of this study, the meta-narrative that a new pension system and a prolonged working life are urgently needed for reasons of demography, national economy and pension system sustainability prevailed among national-level actors such as the government and the social partners.

However, in order to be effective, acceptance at the organisational level is crucial. Yet few statements at the national level mentioned specific organisational economic and efficiency concerns. In a 2013 study, the government experts mentioned wasting human capital, indicating a responsibility of the employers to make efficient use of older workers and the labour supply that they represent. Staffing is a related concern, mentioned in a response from the main public employers’ association (SKR). From our narrative analysis, we can see that the protagonist of the welfare state narrative, in the case of the national-level retirement debate, is the welfare-dependent individual. The welfare system is based on taxes which in Sweden provides free health care to the growing older population, among other things.

Related to these welfare concerns, the villain is mainly older workers who wish to retire early and to some extent the social partners who negotiate early retirement. Those who have supporting roles in this narrative are the policy makers who want to reform the system and change regulations that force the social partners and incentivise older workers in order to extend working lives. In other words, the causal factors involved are the changes in demography that make the current system financially non-sustainable and a belief in (or reliance on) incentives and regulation. This narrative includes an attribution of responsibility on the individual older workers who are impacted by social engineering of policy and collective agreements, and who should extend their working lives more or less voluntarily. The main focus and content of the narrative contains images and concepts such as the dependency ratio.

In contrast, but also partly harmonising it, is the meta-narrative that neo-liberal equal rights and values co-existed in the Swedish national actors’ discussion about retirement. Here the protagonist is the independent (older) individual. The villain in this case is mainly the policy maker, since the regulation uses fixed statutory retirement ages as well as age limits on other social insurances, allowing less choice for the individual. Here, the supporting roles on the national level are mainly played by the social partners, looking for ways to curtail policy reform and retain negotiation latitude for collective or even local agreements, emphasising flexibility or work conditions. In this narrative, the important causal factors are individual freedoms, discrimination (norms), poor work environments and outdated regulation. The attribution of responsibility is on a culture that is youth-oriented, the individuals who make choices and employers who make this possible or not. The content of this kind of narrative is ‘efficient use of human capital’ and forces that ‘coerce older workers to leave retirement both too early and in some cases too late, not being able to choose according to their own needs and wishes’.

The skills reasons for letting older workers go

In comparison to the national-level narratives, the organisational-level narratives showed several differences. As our meeting notes and interview material showed, current age management initiatives in the organisations tended to be based entirely on local considerations, yet traces of the societal meta-narratives could be found in edited forms. A summary of the two organisational-level narratives are found in Table 4. The issue of older workers was framed by two already-existing narratives among the organisational actors: the narrative of competency or skills – unrelated to age – and the business efficiency narrative. Both justified encouraging certain older workers to delay retirement, while the opposite was true for those who were seen as having the wrong skills and if there was no business case for keeping them.

Table 4. Narrating stories of retirement at the organisational level

Notes: Template following Zilber (Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009: 212). HR: human resources.

Despite joining the group with the intention of discussing age management, the HR experts quickly agreed at the first meeting that age was not an issue that was discussed in their organisations:

We don't talk about age, except when someone mentions it. In our new skills strategy, we have removed the word ‘retain’ in relation to people. We just talk about developing.

An example of how this played out in the HR practices was that one of the private manufacturers was running a project for blue-collar workers that was first called ‘Age management’ that targeted employees aged 55+. In this company, physical strain and problems of work ergonomics were described as recurring and leading to sick leave as well as early retirement. However, after about one year the project changed name to ‘Sustainable working life’ in order to include younger employees as well. The actions taken in the project included arranging increased internal job rotation, adapted work tasks and reinstating previously outsourced ‘easy jobs’ in which employees were able to adapt the pace of their work. Also, as a preventive measure, information about the ergonomics of different tasks in the production lines was improved through developing better signs at the workstations. Volunteers were also trained to be ‘health coaches’ who led mini-seminars for their peers.

The issue of age was described by the HR experts in the group as actually being an issue of skills, showing how the narrative was framed and edited during our meetings. For white-collar workers at one of the manufacturing companies, the HR representatives described problems of having enough employees to allow the handover of tasks from older workers to younger ones where new workers worked together with older workers for on-the-job training. Among white-collar workers there was a trend of increasing numbers of individuals who delayed retirement beyond the statutory age, but the company had also seen an increase in variation in the retirement age. In general, older workers were usually not allowed to stay in management positions. ‘It depends on skills, experience ‘and “hunger”’, the HR specialists explained. One of the HR interviewees described how many employees nearing retirement were less interested in developing their skills and the company:

Older workers lose some of their drive to participate in developments, changes and things like that – they come here and do their job and perform a function, but maybe not the way that we want them to: being a part of a work group that drives the work forward.

Another sign of this was the lack of skills with technology mentioned when describing older workers. In nearly all fields, the use of computerised technology was growing.

The HR participants at the meetings also pointed to signs of age discrimination, related to the skills narrative, such as the fact that you are only considered to be a ‘talent’ until you are 55 years old and departments with many ‘seniors’ are given derogatory names such as ‘death's waiting room’. When speaking of white-collar employees, the HR experts at the meeting thus mainly discussed the importance of norms and language. However, none of this was addressed through any specific measures or projects. On the contrary, during the period of the HR group meetings, one of the companies started a new HR-led project which enabled early retirement benefits for white-collar workers in key positions who were willing to be mentors to younger colleagues taking over their tasks. In this way, the older workers were encouraged to leave, thus employing negative norms of ageing related to competence, workability and serviceability.

In general, the HR experts at the meetings said that age is neither a problem nor a resource: ‘we only talk about shifting skills. Skills are being replaced.’ However, when recruitment was discussed, the age of the employees was mentioned and was seen as related to their skills: ‘It is difficult to find the right skills today. Young people are well educated but lack the important experience and networks that older workers have’, the representatives explained. As a contextual condition, the representatives also described the competition for skilled employees on the labour market. At the time of the study, HR supported the managers in recruiting externally in order to find the right skills that were lacking internally: ‘nearly 100 per cent are forced to recruit externally since we can't find these skills within the company’ (Manager). For one of the manufacturing companies, this resulted in many temporary workers, and this was described as a problem, since few of these were older than 50 and most were highly skilled. Thus, younger ‘external’ employees with more updated technical skills were blocked from gaining secure ‘internal’ employment by the older workers. The two groups were thus pitted against each other, and new forms of skills trumped those held by the older workers.

Our narrative analysis of these examples demonstrates that for the organisational actors, the common ‘skills development or shift’ narrative was to some degree edited using the meta-narrative of human rights in those situations where the experience and knowledge of mainly younger workers was acknowledged. For the private-sector manufacturer in the example above, the meta-narrative of the welfare system had no importance, where age is a non-issue except when it came to ‘skills shifting’ and making room for younger employees. As part of this concern, we discerned a plot of going ‘from age to skills as the only issue’. Here, choosing which employees to retain is central to the issue of older workers, even in the face of the difficulties that the organisations had in recruitment, as one HR expert explained: ‘It is only based on what we want to retain.’

The protagonist of this narrative is predictably the employer since HR are representatives of the employer. The issue of working to decrease age discrimination, valuing older workers equally, creating work that is sustainable into older age or taking corporate social responsibility to maintain the welfare system is left out of the talk in the meetings and interviews. It was even actively ignored when introduced by the researchers at the fifth meeting. Instead, the issue of older workers and what was initially called age management is edited to become a question of ‘handing over skills’ and leaving room for a ‘skills shift’. The villain in this narrative is the older individual with the wrong skills, even though they were sometimes described as having important experience and networks.

In the narrative of organisational skills – as unrelated to age, the main supporting roles were played by HR and managers. HR is responsible for both developing employees’ skills and recruiting new employees, while agreements to retire are mostly made between the manager and employee, where the managers have the information on the perceived motivation and skills of the employees. The narrative also included causal factors which viewed the process of ageing (beyond a certain peak point) as a process of declining competence, such as individuals losing their motivation or ‘drive’ as they near retirement age, updated technological skills and the role of the individual in maintaining their own skills development.

Co-existing narrative: the business case for keeping older workers longer

The participants in the study from both public- and private-sector organisations described spending a lot of time and energy on attracting new employees with the right skills or willingness to work in their organisations, which they found to be difficult. Historically, the public-sector organisations had been permitted less investment in employer branding compared to the private-sector organisations. For the public-sector organisations, letting older workers leave early was more often described as a problem in the face of a substantial labour shortage. However, when it came to keeping older workers and encouraging them to delay retirement, the statutory retirement age was still the norm even if some workers continued on temporary and part-time contracts beyond the age of 67.

Even among the public-sector organisations, not all older workers were seen as a resource. For example, one limitation among prison guards is that poor physical strength and slow reactions is a safety issue. Similarly, for older workers in municipal health care, the physical demands could be too great. In contrast, knowledge workers such as, for example, older teachers and trainers working in rehabilitation programmes and the in-house education system in the prison system, as well as in the public school system, have gained valuable experience and are more often seen as a resource. It was described as relatively easy to get these individuals to stay on or come back when needed temporarily, compared to those employees who had physically demanding tasks. A few of those with physically demanding tasks also change jobs inside the organisation in order to continue working, e.g. starting to work in the non-custodial prison programmes where safety and the risk of violence was less of an issue.

Also, in the public-sector organisations there were some cases where retired employees were asked to come back for specific projects or temporary tasks. The managers were careful to underscore that the employer chooses who can work after retirement, depending on the utility of the individual for the organisation and how the person has aged. This excluded those who expressed bitterness and/or confusion, lacked technical skills, which was associated with cognitive decline, and those who showed signs of physical decline:

There is a lot of administrative work that is computer-based, and there I hear that the older workers lag behind, in all those systems. But in the meeting with the client they are super-skilled. Then they are not so good at filling out the action plans and so on. The older workers are described as a little ‘birdbrained’, and that doesn't work here. Then it can be the physical aspect, but that isn't as big a part, it is more when the person can't follow. (HR)

Several participants also described older workers as bitter or demotivated from a lack of appreciation for their tacit knowledge from the employer. However, they described wanting to retain the experience and the skills of certain older workers.

The regulations require that an individual assessment is made in order to keep someone on after they turn 67. As is most common in HR, there was a division between those experts who worked with recruitment and skills development of employees and those who worked with work exits and ‘terminations’. For example, the Swedish Prison and Probation Service gave this as a reason why there was no common or structured approach to delaying retirement, despite a long-standing shortage of labour. Instead, we were told of an organisation-wide HR programme which was partly started in order to change a ‘negative culture and attitudes among older workers’. The programme centred on knowledge exchange and peer encouragement among employees. The programme was described at the meetings as a measure which might have the effect of supporting older workers to delay their retirement, yet this was never measured and nor was it the explicit goal. Instead, in the programme, older workers shared their experience with the younger workers in order to change their attitudes.

From these examples, our interpretation is that the meta-narratives of welfare system efficiency and individual rights are invisible in the organisations, with a distinct emphasis on the already-existing business efficiency narrative as a framework for talking about older workers. We see a plot for the business case narrative about older workers as going from ‘early retirement’ to ‘selecting needed, fit and flexible older workers’. Fitting with this plot were stories of useful, experienced older workers who stay on, but this was only seen as valuable if the older worker was still motivated and fit enough for the task. In this narrative, it is clear that it is the employer who is the protagonist, again unsurprisingly. There is much competition in the market and these organisations lose many employees every year to competitors. Particularly the private-sector organisations highlighted the market demand for technological development as the reason behind the need for new employees, making market forces a villain when it comes to the business case for keeping older workers.

In other words, in this narrative retirement is seen as a possibility to hire people with experience and enough physical stamina, which is described as ‘the naked truth’. The business case narrative was thus edited down to an issue of sustainable working life when framed by the need for manpower. At the later meetings when the skills shift focus was established, the HR experts discussed how it was difficult to adapt work tasks for the older workers who are ‘a bit more worn around the edges’ (Manager). Older workers are thus expected to perform equally compared to younger colleagues, both when it comes to administrative tasks and physically demanding jobs. Some older workers are not able to ‘keep up’. In the case of one of the manufacturing companies, there was a history of outsourcing and downsizing, leading to early retirement deals with older workers: ‘Giving people older than 63 these [early retirement] packages, that was common in some periods. But it hasn't happened lately, the last 5–6 years’ (HR). Previously, external recruitment was done because of rationalisations and downsizing: ‘During the last 10–20 years we have solved it by outsourcing some parts of operations.’

Continuing with this organisational narrative, the HR department and line managers have important supporting roles with regard to the older workforce and to selecting those individuals who are sustainable in their jobs. Those in the supporting roles thus helped the protagonist employer in working out how to handle the maladjusted older workers, such as in the example of the knowledge exchange workshops in the Prison and Probation Service, in order to move forward along the line of the plot, recognising and encouraging individuals who have aged successfully in the organisation. The causal factors in this narrative are that older workers are often dependent on special measures in order to continue working, or they expect early retirement when it has been customary historically. Managers who are unaware of the business case for keeping selected employees and thus fail to contribute to this kind of organisational efficiency are also seen as causal factors. In line with this organisational narrative, the main attribution of responsibility for it being difficult to retain and sustain the right older workers is on HR and line managers. Also, management is attributed responsibility for valuing the employees and making them feel appreciated. Issues related to creating norms that create a better psycho-social work environment were thus highlighted in the business case for retaining selected older workers. ‘Being seen’ and appreciated was often described as equal to a good work environment.

In summary, both of the organisational narratives that we interpreted as representing the discussions on the HR issues about older workers resulted in the following: if a key person with the right skills, physical strength, cognitive abilities and motivation wants to work longer, then the organisation will support it. In some cases, the organisations search for and select these individuals or provide some limited special measures to decrease the demands and physical strain in their work. However, in general the organisational representatives were not interested in prolonging working life among employees beyond the statutory retirement age, and sometimes not even that long. Evidence of this could be seen in that the organisations were not offering people anything extra to stay longer, despite ongoing recruitments. Part-time retirement, which is a classic benefit for extending working life, was mainly available to white-collar managers and was decided by their own manager.

Discussion and conclusions

Our analysis has traced the relationship of the national meta-narratives at the policy level, in this case in Sweden, regarding retirement timing to organisational (employer) narratives. We found that the dominant narrative at the national level concerned the need to delay retirement in order to increase and maintain the efficiency of the welfare system. A sub-narrative co-existed that dealt with the individual's rights, in this case the right to choose the timing of retirement. However, among a selection of Swedish HR experts representing the organisational/employer level, few traces or translations of these meta-narratives could be found in discussions regarding older workers. Instead, at this level, the employer's construction of the narratives regarding retirement timing was framed in terms of two other ongoing larger narratives of managing skills (knowledge), and optimising operational efficiency and ‘a business case’.

Thus, the national-level meta-narratives mostly addressed the individual and the social partners rather than organisations employing older workers. The employers in the study framed the problem of increasing numbers of older workers to fit into two narratives which both lead to a careful selection to retain only the most skilled, competent, motivated and physically, as well as cognitively, strong older workers. This is opposite to the dominant ‘delay retirement’ narrative of preserving the welfare system, which is promoted at the national level. We assume here that the social partners in the employer association and labour union narratives were influenced in turn by their respective local memberships of employers and employees, yet the issue of how to manage everyday HR tasks is still missing at the society-level (public) as well as the organisational-level debate. For this reason, we describe the employers and HR as ‘missing actors’, both in the national debate, and in the stories of retirement that the organisations tell. The organisational narratives instead talk about recruitment, skills ‘mixes’, the individual's motivation, minimising costs for developing and ‘retaining’ employees, and improving the business case.

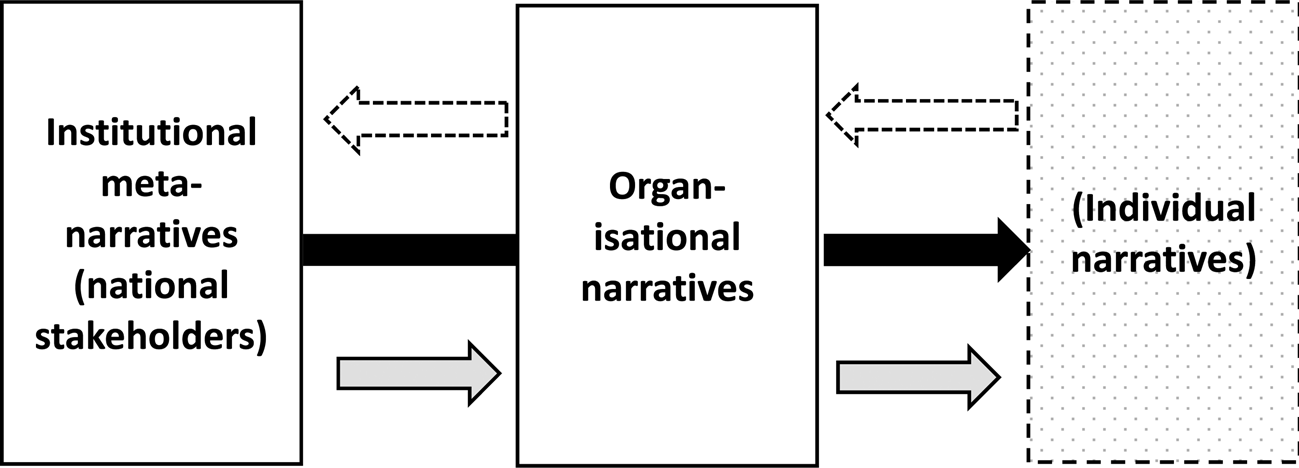

Using the model of translation between different social levels of narratives (see Figure 1), the arrow going from the national-level meta-narrative is thus mainly directed at the individual. The effort is towards creating incentives and norms so that older individuals can contribute to maintaining the welfare system by delaying retirement. At the national policy level, there is also resistance from the social partners to any suggestion of placing responsibility on the employers. Our analysis showed that taking this kind of responsibility for the welfare state in Sweden is not considered an issue at the organisational level, and responsibility is instead attributed to recruiting new skills or demonstrating the business case for selecting particular older workers to retain.

Figure 1. The studied chain of translations of institutional narratives with respect to ageing, work and retirement.

Note: Solid arrow: strong relationship; grey arrow: weak relationship; broken line arrow: not studied.

Source: Adapted from Zilber (Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009).

In the current situation of labour shortages, employers who select specific ‘productive older workers’ and then allow and encourage them to continue working beyond retirement (often precarious employment; see Lain et al., Reference Lain, Airey, Loretto and Vickerstaff2019) fit with the national-level plot of viewing them as a resource. At the same time, this allows a sub-group of older workers to choose if they would like to continue their employment beyond the statutory age of retirement, in line with the national plot of the individual's right to choose. Yet, the selection of older workers whom the employers take an interest in seems to be small. Employers make few specific efforts to adjust work tasks, career development or working conditions in order to fit the needs and wishes of a wider group of older workers. There was only one exception in our study: adjusting the physical demands on some older blue-collar workers in a manufacturing organisation. Even in this case, the bulk of the effort was on preventive measures that benefited the health of all workers and the issue of specific measures for older workers was considered illegitimate.

Our findings thus demonstrate that the practices of the organisations were coloured by institutional work practices, particularly regarding the creation of meaning, i.e. narratives that have developed over long periods of time in order to frame internal policies and routines (Lawrence and Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006; Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin, Suddaby, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2008). In this case, early or statutory retirement norms in the organisations remained strong, viewing older workers mainly as in a state of decline, as seen in previous studies (Tretheway, Reference Trethewey2001; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Brooke, McLoughlin and Di Biase2010; Earl et al., Reference Earl, Taylor and Cannizzo2018; Phillipson et al., Reference Phillipson, Shepherd, Robinson and Vickerstaff2019). Also, our narrative analysis demonstrated that age management and delay of retirement in the studied organisations centred around difficulties in recruiting ‘new blood’, a metaphor that has been described in a previous study (Riach and Kelly, Reference Riach and Kelly2015). The older workers were mainly seen as blocking the entry of new, more technologically savvy and motivated employees with updated knowledge and skills, similar to the finding of Taylor et al. (Reference Taylor, Brooke, McLoughlin and Di Biase2010).

These institutionalised cultural norms among employers appear to be independent of the narratives presented at the societal level. In previous studies, similar narratives have been subject to change only through translation to organisational-level concerns (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Scully and Austin2002; Zilber, Reference Zilber, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2008; Haack et al., Reference Haack, Schoeneborn and Wickert2012; Landau et al., Reference Landau, Drori and Terjesen2014) or the introduction of ruptures and ante-narratives (Adorisio, Reference Adorisio2014). However, in this case the framing of the issues using ongoing organisational narratives counteracted any potential effects of the national-level framing. Thus, the promotion of the skills and business case narratives accomplished mainly the institutional maintenance work – continuing to exclude many older workers from extending their working lives.

The theoretical contribution of our study is twofold, firstly bringing the organisational actor into the foreground through narrative analysis of the situation for ageing workers seen from a multi-level perspective. This is a contribution to previous studies of narratives and the discourse of retirement timing and norms regarding older workers and ideal workers in society (see LaLiberte Rudman and Molke, Reference LaLiberte Rudman and Molke2009; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Billett, Dymock and Martin2012; Pritchard and Whiting, Reference Pritchard and Whiting2014; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Hardy, Cutcher and Ainsworth2014; Riach and Kelly, Reference Riach and Kelly2015; Hewko et al., Reference Hewko, Reay, Estabrooks and Cummings2018). Studying the linking of organisational-level actors is less common since most studies are concerned with individuals’ own narratives (Tretheway, Reference Trethewey2001; Henkens and Leenders, Reference Henkens and Leenders2010; Smith and Dougherty, Reference Smith and Dougherty2012; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Chaffee and Sonnega2016; Lain et al., Reference Lain, Airey, Loretto and Vickerstaff2019) and the narratives in the media or in policy debate (LaLiberte Rudman and Molke, Reference LaLiberte Rudman and Molke2009; Flynn, Reference Flynn2010; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Billett, Dymock and Martin2012). The comparison with the national-level narratives in our study showed that the organisations acted through other narratives, with institutional maintenance as the result.

Within the field of narrative theory, we contribute particularly to studies of narrativisation when it comes to multiplicity, i.e. the co-existence of narratives. In our study, the employer's and manager's story is dominant, legitimising the need to select the right employees who get to stay. The narrative of valuing older workers’ rights and freedom of choice weighs lightly but is harnessed when needed, which is only when there is a shortage of specific labour or skills in the organisation that the older workers have. This shows the importance of context for narratives, such as current labour market conditions. If or when these conditions change, as they have in the past, the fuel for the narrative elements of causal explanations and attribution of responsibility are likely to change. This relates to previous studies that have followed the longitudinal development of co-existing organisational narratives which have clashed and eventually changed (Zilber, Reference Zilber2002, Reference Zilber, Lawrence, Suddaby and Leca2009; Haack et al., Reference Haack, Schoeneborn and Wickert2012; Adorisio, Reference Adorisio2014; Landau et al., Reference Landau, Drori and Terjesen2014). The consequences of the co-existing organisational-level narratives merit continued studying of the micro-foundations of the institution of the welfare state when it comes to retirement.

Secondly, and following on from the previous discussion, many of the earlier studies of multiple meta-narratives inside organisations showed that eventually one narrative comes to dominate. If the multiplicity of meta-narratives gives a kind of freedom to combine or choose, then a ‘simplicity’ and lack of pluralism also hides conflicts or differing interests. In our study, the dominance of the business case organisational narratives represented this type of simplicity. At the policy level, negotiating differing interests is part of the work that is explicit, while inside organisations, creating one dominant narrative in order to ‘co-ordinate action’ is more accepted or expected. This locks the narrativisation process and blocks changes in both meaning and organisational practices, in other words the social action of the narratives (Zilber, Reference Zilber, Mir and Jain2017). Other studies have also noted the detrimental effects of the business case as the only meta-narrative to support the prolonging of working lives, ignoring the meta-narrative of corporate social responsibility (Kulik et al., Reference Kulik, Perera and Cregan2016). Another possible narrative direction is a co-option of the business case narrative in order to strengthen the position of older workers (Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2015; Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016). This study has thus contributed another empirically relevant case to the stream of studies within the field of institutional work which are interested in narrative meaning structures and institutional maintenance.

Finally, this study contributes to knowledge of organisational practices relating to older workers, i.e. ‘age management’. As compared to the national-level narratives, the organisational actors had a more nuanced picture of older workers, viewing older workers as more heterogeneous. The social partners and employers were also negatively disposed to general solutions, though in some cases employing general programmes themselves, such as the studied ‘Sustainable working life’ and ‘knowledge exchange’ HR projects. The narrative analysis is useful for contributing to practice: clearly, the attribution of responsibility and the portrayal of the villain are related to what types of action gain legitimacy and are promoted in an organisation. For example, when older workers are seen as villains and less productive, and the employer is the sole hero, then the responsibility is placed on the individual to resist the ageing as decline narrative in order to be still seen as productive – or else to retire and not become a burden on the organisation (see also Tretheway, Reference Trethewey2001; Riach and Kelly, Reference Riach and Kelly2015). However, if the individual retires, he or she is instead a burden on the nation's welfare system, according to the national-level narrative. This double whammy found in our study is similar to the increasing uncertainty and precarity for individuals nearing work endings, as described by Phillipson et al. (Reference Phillipson, Shepherd, Robinson and Vickerstaff2019). It also confirms earlier studies of the influence of neo-liberal ideas on retirement narratives (LaLiberte Rudman and Molke, Reference LaLiberte Rudman and Molke2009).

Also, in our case the dominance of the business case and skills narratives begs the politically charged question: who fits the definition of the ‘desirable older worker?’ It seems that at the end of an employee's career, the dominant narrative constructs a new recruitment situation all over again, in a similar way to the start of a career. If we continue the analysis of metaphors started by Riach and Kelly (Reference Riach and Kelly2015), the vampire organisation is bleeding through a major wound, i.e. losing the skills and labour of those who retire, and is still mainly insisting on fresh blood, i.e. recruiting new and younger employees, instead of repairing the wound. Another image could also be the classic machine metaphor often used for organisations. In this case, the older workers are seen as cogs that must fit the mould or be quickly discarded and replaced in order to keep the wheels turning.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forte) (dnr 2015–01006); the Forte-Centre Aging and Health: Centre for Capability in Ageing (AGECAP) (dnr 2013–2300); and the University of Gothenburg, UGOT Challenges.