Introduction

The working world is changing. The office cubicle is being replaced by beanbags; laptops and smartphones allow you to work anywhere; and virtual meeting rooms connect you with your co-workers overseas. Companies, such as Google or WeWork, have begun to implement climbing walls, theme-park-style meeting rooms, and slides between floors. Furthermore, employees have come to expect high-end designer furniture, napping areas, and free barista coffee, and they might even consider such perks to be a basis for their decision in favor of or against a potential employer. It, thus, comes as no surprise that many organizations are implementing so-called creative spaces to attract future employees, to express their innovative corporate culture, and to increase communication and creativity among their personnel. Simultaneously, research is investigating the impact that the physical work environment can have on the innovation process. This paper provides a systematic literature review on the topic of creative spaces to shed light on the current state of related research.

We define creative spaces as physical structures and elements at different scales that are deliberately designed to support creative (e.g., designerly) work processes. The terms “creativity” and “innovation” are often used differently and sometimes interchangeably in the literature. Amabile (Reference Amabile1988, p. 126) defines creativity as “the production of novel and useful ideas by an individual or small group of individuals working together”. According to most definitions, innovation includes the concept of creativity and extends it with the aspect of the successful organizational implementation of an idea (Amabile, Reference Amabile1988, p. 127). We argue that both aspects – creativity and innovation – can be facilitated by a creative space. Creative work processes can be defined as the complete process of a creative task or innovation project, which encompasses activities like desk or field research, individual or team ideation, prototyping, testing, and presentation. Consequently, we focus our research on spatial designs that facilitate the entire creative work processes and, hence, are relevant to creativity and innovation.

The range of scales of creative spaces varies in size and scope and includes single items and pieces of furniture, the room's layout and interior design, the architecture of the building, and the location within a specific civic context. The term “creative space” covers spaces in both educational and corporate environments. Sub-categories include innovation labs (also called idea labs), makerspaces (also called hackerspaces or Fablabs), and incubators. Innovation labs are “deliberately established locations, where individuals and teams with new product ideas can work together for concentrated bursts of time” (Narayanan, Reference Narayanan2017, p. 27). In contrast, a makerspace is “characterized as a publicly accessible workshop which provides members with machines and tools and offers access to a creative community” (Böhmer et al., Reference Böhmer, Beckmann and Lindemann2015, p. 8). Incubators and accelerators “operate in the later stages [of the innovation process] and are built to facilitate a startup” (Narayanan, Reference Narayanan2017, p. 29). Another related concept is co-working spaces. These, however, are simply spaces that “enable people from diverse backgrounds to work together in a common space” (Roth and Mirchandani, Reference Roth and Mirchandani2016, p. 1). According to this definition, co-working is not specific to creative work but rather assembles a heterogeneous group of people at one workspace.

This paper is not limited to general office environments, although creative work (as defined above) is becoming more and more important in non-creative disciplines as well (Framework for 21st Century Learning - P21, n.d.). Instead, we focus on creative office and learning spaces and idea labs, but not on co-working spaces, makerspaces, or incubators.

While extensive research has been conducted on work environments in general and office productivity, research about the specifics of creative spaces is still in its infancy. What is lacking is a holistic understanding of the possible impact of workspace design on creative work activities. As Amabile stresses, “there is almost no empirical research on the effects of work environments on creativity” (Amabile, Reference Amabile1996, p. 210). However, since the publication of her (updated) book in 1996, numerous studies have been conducted that address this topic, which leads to the following research question:

RQ: How can the spatial design of workspaces in academic and corporate environments facilitate creative work, according to the current state of the literature?

Recently, public interest in creative environments has increased – as can be inferred from the large number of coffee-table books on the topic of creative office spaces. Simultaneously, an increased interest in creative learning environments is emerging in the area of elementary schools and kindergartens. Furthermore, some hybrid types of work environments – such as co-working spaces, makerspaces, and FabLabs – as well as innovation labs and incubators are covered by such illustrated books.

At the same time, various industrial corporations, such as furniture manufacturers, architecture firms, and real estate companies, have conducted research about creative workspaces. While these publications are usually not peer-reviewed, they still provide novel research on various practice-related topics. Since these companies usually have access to a large number of customers or employees, they are able to conduct quantitative research that is of high practical relevance. For example, M. Arthur Gensler Jr. & Associates, Inc. (known as Gensler) is a US architecture and design firm based in San Francisco. They regularly publish workspace surveys – the so-called Gensler Workplace Survey – in which they present the results of surveys done with office workers, mainly in the US. More recently, they have also included issues for the UK, Asia, and Latin America. In the latest US issue from 2016 (Gensler, 2016), they surveyed a panel-based sample of more than 4,000 randomly selected US office workers from 11 industries. The goal of the survey was to understand “where, and how, work is happening today, and the role design plays in employee performance and innovation, […] to provide critical insight into how the workplace impacts overall employee experience” (Gensler, 2016, p. 3). One main finding was that “great workplace design drives creativity and innovation” (Gensler, 2016, p. 3). They identified four modes for successful work performance: focus work, collaboration, learning, and socializing (Gensler, 2008).

American furniture manufacturer Steelcase also conducted research about various interior-related topics, such as “well-being”, “the privacy crisis” at the workplace, or “active learning spaces”. Their findings were published in their internal magazine called 360°. Two of the latest issues – “The creative shift” (Steelcase, 2017) and “Inside innovation” (Steelcase, 2018) – focus on creativity and innovation in the workplace. These issues discuss scientific insights, for example, the effects of posture on the brain or the impact of social interaction on creativity, in terms of alignment with Steelcase's furniture concepts.

Similarly, Knoll, another US furniture manufacturer, regularly publishes short papers about various topics related to the workplace and learning environments under the label “Knoll Workplace Research”. Among the studies presented, there were survey results and case studies related to, for example, ergonomic questions, startup culture, and future work, and technology trends. Of particular interest for the topic of creative spaces is the article on “The rise of co-working” (Roth and Mirchandani, Reference Roth and Mirchandani2016), which presents statistical data and demographics about co-workers and their preferences, and the article “Adaptable by design” (O'Neill, Reference O'Neill2012), which addresses the importance of flexible and customizable workspaces.

These examples demonstrate an increased public and corporate interest in the topic of creative working and learning environments that warrants further investigation. Accordingly, the aim of this paper is to systematically analyse the current state of research on creative workspace design.

This paper is structured as follows: First, we present our methodological approach for identifying the relevant literature for inclusion in our discussion. Subsequently, we outline our main findings, categorized into (1) types of theoretical and practical contributions, (2) spatial impact on creative work, and (3) technological focus. We conclude by discussing the findings and presenting an outlook on future work.

Methodology

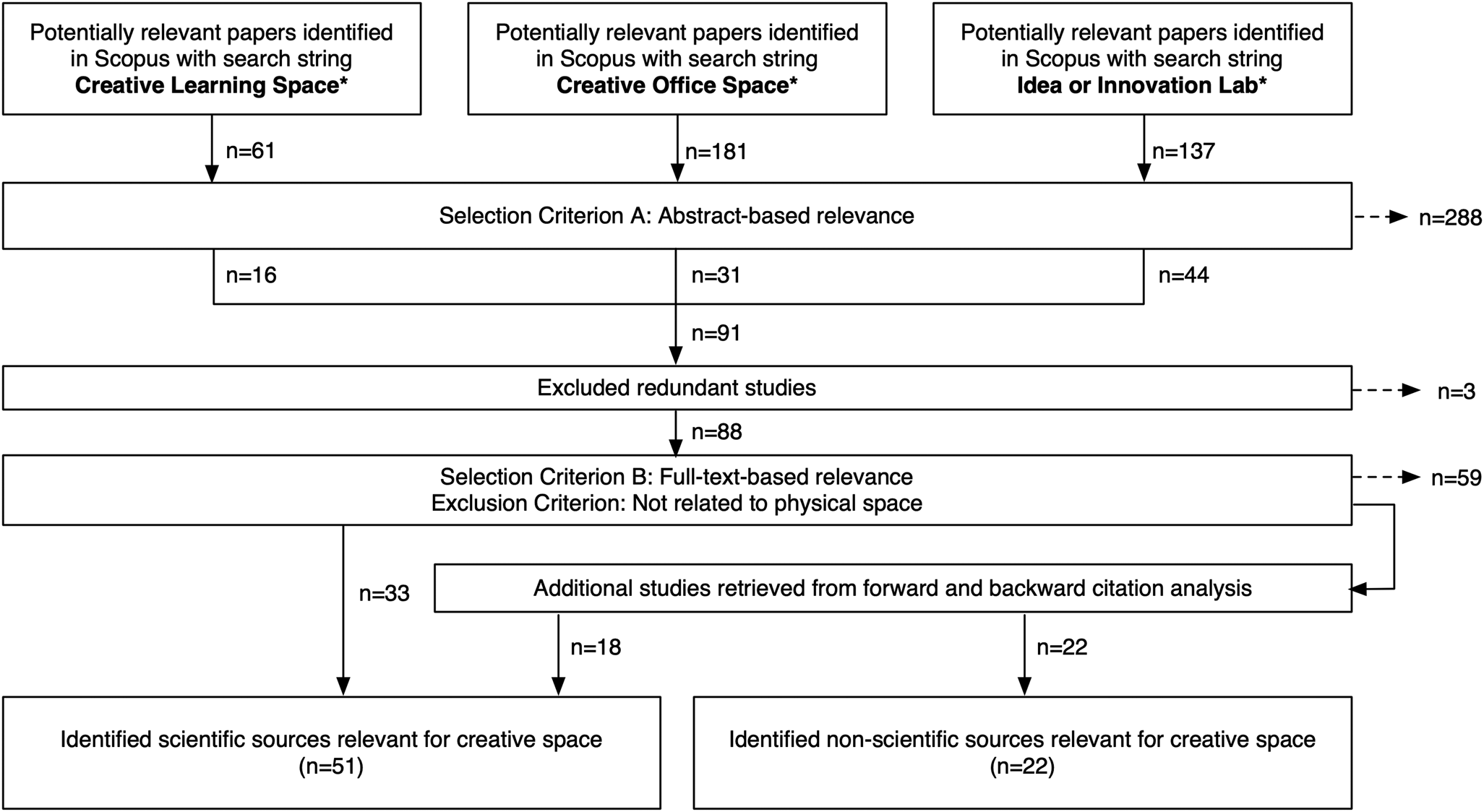

To identify potentially relevant academic sources, we conducted a keyword search within the Scopus database. We started by searching with the two general keywords “creative AND space”, but this resulted in an unmanageable number of sources (15,000+), which included numerous false positive hits (e.g., addressing outer space). When looking into coffee-table books about creative spaces, we identified three domains of interest: (1) creative office spaces, (2) creative learning spaces, and (3) hybrid forms, such as laboratory spaces, co-working spaces, incubators, and makerspaces. Based on this categorization, we then conducted a three-step search with fixed keywords within the Scopus database. More specifically, we searched for the literature on (1) “creative office space”, (2) “creative learning space”, and (3) “idea lab” or “innovation lab”. For the hybrid forms, we included only idea labs and innovation labs into our search process, because (a) co-working spaces were considered not specific to creative work, (b) incubators were considered not specific to creative work as well, but rather an environment for implementing business ideas, and (c) makerspaces were considered only a sub-category of creative spaces that would not address the entire creative process but only the prototyping step. By contrast, idea labs and innovation labs were considered an environment for specifically developing creative ideas and, hence, were included as a separate search string.

For all three searches, possible combinations with synonyms were also considered (e.g., “space” vs. “environment”, “creative” vs. “innovative”, “office” vs. “work”, “learning” vs. “education”, and “lab” vs. “laboratory”). The results were limited to only peer-reviewed journal and conference publications. The time range of included sources spans from 1999 to 2018.

First, we analyzed the 379 identified sources based on their abstracts. We excluded papers that were either unrelated to the topic of creative workspace design or limited to one specific aspect of the environment (e.g., lighting, ergonomics of office chairs, etc.) because we were particularly interested in overview papers that contribute to a systemic view on the topic, and we also excluded papers that addressed a peculiar (non-design-related) context, such as hospitals, libraries, or nursing homes (selection criterion A). From the hybrid domain, sources about makerspaces or co-working spaces were included in our sample when they were part of the bigger system of a creative space.

After excluding redundant sources from all three search steps, we conducted a full-text analysis on the remaining 88 sources, which left us with 29 sources identified as relevant. Our selection criterion at this point was to include only papers with a focus on the physical environment, whereas sources that viewed the environment in a rather abstract way (e.g., financial constraints, encouraging leadership, or virtual spaces) were disregarded (selection criterion B). Finally, we conducted a backward and forward co-citation analysis on the remaining 29 sources, in which we also included non-peer-reviewed sources, such as books and PhD theses, as well as coffee-table books and corporate research that appeared to be of relevance. This procedure resulted in a total of 51 scientific sources and 22 non-academic sources that were included for further analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the systematic search process.

Fig. 1. Systematic literature search process.

Results

We will discuss the 51 academic sources and 22 non-academic sources by applying three different lenses of interest: (1) We distinguished among seven types of theoretical and practical contributions that the sources provide (five types of theories, existing literature reviews, and tools). (2) The main interest of our investigation was the spatial constructs that would have a positive impact on creativity and innovation efforts, as suggested by the analyzed literature. For this step, we distinguished among (a) the space types for different creative activities, (b) the requirements for those spaces, (c) concrete spatial design suggestions, and (d) intangible aspects. (3) Finally, we explored the utilization of technological advancements and artificial intelligence (AI) in the design of and research on creative spaces. Figure 2 shows the analysis schema that illustrates our three lenses of interest for analyzing the literature.

Fig. 2. Analysis schema.

Types of theoretical and practical contributions

As a first step in our content analysis, we were particularly interested in exploring the theoretical and practical contributions of the discussed sources. Gregor (Reference Gregor2006) distinguished among five types of theories that we used to categorize the analyzed sources. We slightly renamed the theory types to add clarity.

Theories for analyzing (Type 1) only describe and analyse the reality – for example, as a framework, classification system, typology, or list of categories or requirements. Interpretative theories for explanation (Type 2) attempt to explain specific incidents. They provide a deeper understanding of a complex situation – for example, through rich, qualitative data. Theories for prediction (Type 3) attempt to predict certain incidents but without providing causal explanations. Causal theories for explanation and prediction (Type 4) attempt to predict specific incidents and also provide testable propositions and causal explanations. Design theories (Type 5) provide explicit prescriptions for constructing an artifact (i.e., explain how to do something).

Consequently, we categorized the identified sources according to their theoretical contribution. In the following section, we discuss one source per category in more detail to illustrate the theory types (a discussion of all sources per category would exceed the length of this paper).

Theories for analyzing, Type 1. Most of the analyzed academic sources (n = 19) present Type-1 theories that describe a creative space as is. From these 19 sources, 11 present structured typologies, classification systems, or frameworks (Snead and Wycoff, Reference Snead and Wycoff1999; Jankowska and Atlay, Reference Jankowska and Atlay2008; Leurs et al., Reference Leurs, Schelling and Mulder2013; Williams, Reference Williams2013; Setola and Leurs, Reference Setola and Leurs2014; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Brinks and Brinkhoff2015; Kohlert and Cooper, Reference Kohlert and Cooper2017; Paoli and Ropo, Reference Paoli and Ropo2017; Thoring et al., Reference Thoring, Desmet and Badke-Schaub2018a, Reference Thoring, Luippold and Mueller2012a, Reference Thoring, Luippold and Mueller2012b). In contrast, eight sources present unstructured lists of requirements that a creative space should fulfill, but without detailing how exactly this could be achieved (Lindahl, Reference Lindahl2004; Haner, Reference Haner2005; Moultrie et al., Reference Moultrie, Nilsson, Dissel, Haner, Janssen and Van der Lugt2007; Martens, Reference Martens2008; Walter, Reference Walter2012; Oksanen and Ståhle, Reference Oksanen and Ståhle2013; Peschl and Fundneider, Reference Peschl and Fundneider2014; Narayanan, Reference Narayanan2017).

One example of these 19 sources is the typology presented by Paoli and Ropo (Reference Paoli and Ropo2017), which suggests, based on empirical investigations of 40 companies’ workspace pictures found on the internet, a set of five spatial themes that might foster creativity in the workspace. The five identified themes are (1) home, (2) sports and play, (3) technology (imaginative future and past), (4) nature and relaxation, and (5) symbolism, heritage, and history. For each of the five themes, they present spatial resemblances, such as stylistic decors and furnishings. However, as is typical for Type-1 theories, they do not provide any predictions or explanations as to how these themes would be able to facilitate creative work processes.

The majority of the non-academic sources, and particularly the coffee-table books on the topic, can be categorized as a Type-1 theory. For example, illustrative books on creative office space (Stewart, Reference Stewart2004; Groves et al., Reference Groves, Knight and Denison2010; Borges et al., Reference Borges, Ehmann and Klanten2013; Georgi and McNamara, Reference Georgi and McNamara2016), creative learning spaces (e.g., Boys, Reference Boys2010; Dudek, Reference Dudek2012, Reference Dudek2000; Ehmann et al., Reference Ehmann, Borges and Klanten2012; Mirchandani, Reference Mirchandani2015), and co-working spaces and makerspaces (e.g., Davies and Tollervey, Reference Davies and Tollervey2013; Kinugasa-Tsui, Reference Kinugasa-Tsui2018) are placed in this category. All these books merely present a collection of photographic case examples of peculiar creative spaces that are visually stunning and beyond the ordinary. However, they rarely provide any theoretical background or explanations about the possible impact of the spatial designs. Seldom are these books categorized systematically, and no theoretical underpinning about possible reasons why the spaces are designed as they are is provided. Similarly, some editions of the Knoll Workplace Research present surveys and case studies on various space-related aspects, thus describing the status quo rather than providing any further explanations or predictions.

Interpretative theories for explanation, Type 2. Ten identified sources present qualitative or interpretive theories that try to explain more complex situations related to particular spatial configurations. These explanations are mainly based on qualitative user studies and individual opinions, such as interviews or case studies. They do not provide any testable propositions or predictions (Kristensen, Reference Kristensen2004; Törnqvist, Reference Törnqvist2004; Lewis and Moultrie, Reference Lewis and Moultrie2005; Greene and Myerson, Reference Greene and Myerson2011; Bryant, Reference Bryant2012; von Thienen et al., Reference von Thienen, Noweski, Rauth, Meinel, Lang, Plattner, Meinel and Leifer2012; Cannon and Utriainen, Reference Cannon and Utriainen2013; Edström, Reference Edström2014; Thoring et al., Reference Thoring, Luippold, Mueller and Badke-Schaub2015a; Groves-Knight and Marlow, Reference Groves-Knight and Marlow2016).

One example is presented by Lewis and Moultrie (Reference Lewis and Moultrie2005), who conducted three case studies in innovation laboratories, supplemented by 14 interviews with managers. They compared structural (e.g., architectural) and infrastructural (e.g., equipment) elements. The paper then presents a summary of possible benefits and potential drawbacks of these elements for an organization. Among the benefits discussed are a dislocation from the everyday environment and the possible elimination of organizational hierarchies. Furthermore, Lewis and Moultrie (Reference Lewis and Moultrie2005) identified innovation labs as a reinforcement factor for employees’ commitment to innovation. However, they did not provide any testable propositions or predictions regarding how a specific spatial design would impact these benefits, which is typical for a Type-2 theory.

Theories for prediction, Type 3. Eight of the identified sources present theories with predictions regarding how a specific spatial configuration would facilitate creative work, but without providing explanations (McCoy and Evans, Reference McCoy and Evans2002; Ceylan et al., Reference Ceylan, Dul and Aytac2008; Lin, Reference Lin2009; Magadley and Birdi, Reference Magadley and Birdi2009; Dul and Ceylan, Reference Dul and Ceylan2011, Reference Dul and Ceylan2014; Dul et al., Reference Dul, Ceylan and Jaspers2011; Waber et al., Reference Waber, Magnolfi and Lindsay2014).

For example, Magadley and Birdi (Reference Magadley and Birdi2009) used a mixed methods approach, including a field experiment, to measure the quality and quantity of ideas developed in an innovation lab. They found that the innovation lab outperformed the normal workplace in both quantity and quality of generated ideas. However, they do not provide theoretical explanations that explain this effect, which makes this a Type-3 theory.

Some of the analyzed corporate research can also be placed in this category. Steelcase investigated, for example, the impact of posture on the brain and the influence of social interaction on creativity (Steelcase, 2018, 2017).

Causal theories, Type 4. Five identified sources present causal theories, outlining a causal relationship between physical workspace and creativity (McCoy, Reference McCoy2005; Martens, Reference Martens2011; Meinel et al., Reference Meinel, Maier, Wagner and Voigt2017; Paoli et al., Reference Paoli, Sauer and Ropo2017; Thoring et al., Reference Thoring, Gonçalves, Mueller, Badke-Schaub and Desmet2017a).

For example, based on a literature review of 17 articles, Meinel et al. (Reference Meinel, Maier, Wagner and Voigt2017) identified several categories of interest related to creativity-supporting physical work environments: They define five aspects of spatial layout (privacy, flexibility, office layout, office size, and complexity), four space types (relaxing space, disengaged space, doodle space, and unusual/fun space), and several tangible office elements (furniture, plants, equipment, window/view, decorative elements, and materials), as well as intangible office elements (sound, colors, light, temperature, and smell). They summarize the results in a framework, and they suggest several characteristics as supportive of creativity, such as available materials and tools, a good indoor climate, positive smells and sounds, complex shapes and ornaments, decoration and art, and greenery. The reviewed literature provides the theoretical underpinning to explain the suggested effects, which is why this study is classified as a causal Type-4 theory.

Design theories, Type 5. Four of the identified sources present design theories that either provide concrete guidelines or principles for how to design a creative space (van Meel et al., Reference van Meel, Martens and van Ree2010; Doorley and Witthoft, Reference Doorley and Witthoft2012; Thoring et al., Reference Thoring, Mueller, Desmet and Badke-Schaub2018b, Reference Thoring, Mueller, Luippold, Desmet and Badke-Schaub2018c).

For example, Doorley and Witthoft (Reference Doorley and Witthoft2012) present a collection of 63 instructions for designing collaboration furniture or interior design elements. These detailed blueprints include drawings, material suggestions, and even names of suppliers. Furthermore, each blueprint provides links to other blueprints that might be of relevance in that context. Such design principles that provide practitioners with concrete guidelines for designing creative spaces can be regarded as a design theory, according to the definition provided by Gregor (Reference Gregor2002).

Existing literature reviews. Our sample included three literature reviews on the topic of creative spaces (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Jindal-Snape, Collier, Digby, Hay and Howe2013; Jindal-Snape et al., Reference Jindal-Snape, Davies, Collier, Howe, Digby and Hay2013; Beghetto and Kaufman, Reference Beghetto and Kaufman2014). Two additional sources that were already categorized as Type-4 theories also presented systematic literature reviews as part of their studies (McCoy, Reference McCoy2005; Meinel et al., Reference Meinel, Maier, Wagner and Voigt2017). However, none of these five sources appeared to be sufficiently comprehensive. For example, Meinel et al. (Reference Meinel, Maier, Wagner and Voigt2017), who present the most comprehensive and rigorous literature review that culminated in a causal theory, do not include learning spaces. Moreover, their sample size of 17 articles seems rather limited. In contrast to that, Beghetto and Kaufman (Reference Beghetto and Kaufman2014) and Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Jindal-Snape, Collier, Digby, Hay and Howe2013) only focus on educational contexts. For our own literature review, we included these existing reviews in our co-citation analysis to identify additional relevant sources that were possibly not covered by our own search criteria.

In addition to these theoretical contributions, we were also interested in practical contributions – particularly tools provided for designing creative workspaces.

Tools. Our sample yielded only two scientific sources that present tools for developing creative spaces (Thoring et al., Reference Thoring, Mueller, Badke-Schaub and Desmet2016, Reference Thoring, Mueller, Badke-Schaub and Desmet2017b). Two additional sources that provide tools were identified among the non-scientific sources (Dark Horse Innovation, 2018; SAP AppHaus, n.d.). Design thinking consultancy Dark Horse published the New Workspace Playbook (Dark Horse Innovation, 2018), which presents a comprehensive set of frameworks for designing a creative workspace along with visual canvases, available for self-printout. Global software company SAP developed a tool called Mosaic (SAP AppHaus, n.d.) for co-creating a creative work environment that consists of a set of hexagonal cards that address different categories of a creative space. The cards facilitate the co-creation of a future work environment.

The two sources by Thoring et al. (Reference Thoring, Mueller, Badke-Schaub and Desmet2016, Reference Thoring, Mueller, Badke-Schaub and Desmet2017b) focus on educational environments. They present a set of co-creation canvases and card sets that should be used in a co-creation approach to develop creative workspaces involving all relevant stakeholders. The tools were developed based on a design science approach (Hevner et al., Reference Hevner, March, Park and Ram2004) and evaluated in an action design workshop (Lewin, Reference Lewin1946).

In this section, we analyzed the sources included in our review in terms of their theoretical and practical contributions; the next section addresses the main focus of our research – namely, which spatial characteristics would have a positive impact on creative work.

Spatial impact on creative work

The analyzed sources provided insights into various aspects of spatial designs in creative work and study environments. We examined these sources according to the following criteria: (1) what different types of spaces were considered relevant to creative activities (i.e., what activity should the space support?); (2) what kind of requirements for creative spaces were mentioned (i.e., what effect should the space provoke?); and (3) what concrete physical characteristics as well as (4) what ambient characteristics should the space have in order to facilitate creative activities (i.e., how should the space be designed?). The results from these four questions are summarized in Tables 1–4.

Table 1. Overview of addressed space types for different creativity-related activities

Table 2. Overview of suggested abstract requirements of a creative space

Table 3. Overview of mentioned concrete characteristics of a creative space

Table 4. Overview of mentioned intangible aspects of a creative space

Types of spaces relevant to creativity and innovation

In the first step of our analysis, we examined which space types the 51 analyzed sources identified as relevant to creative activities. Table 1 presents an overview of sources that mentioned different space types for different creative activities, regardless of whether or not these space types were presented as a structured typology (as outlined in the previous section) or simply mentioned within the text.

When looking at the 12 space types suggested by the analyzed sources, six larger categories can be identified: (1) spaces for individual work (includes personal space, focus space, incubation space, and reflection space); (2) spaces for collaborative work (includes team and meeting spaces); (3) spaces for making (includes experimentation spaces, analysis spaces, verification spaces, and workshop spaces); (4) spaces for presenting (includes lecture spaces, but also exhibition spaces); (5) spaces for preparation that are not necessarily part of the regular work environment but still integrated into the work process – for example, to do research (includes exploration space and research space); and (6) spaces that are somewhat outside the regular work process, where people take a break and transit between spaces (includes intermission space, disengaged space, relaxation space, and well-being space). The “illumination space” is not clearly defined by most authors. Some do not specify it at all, others mention a “retreat space” that can trigger new insights. We argue that this sudden triggering of insight could occur in any space type, but especially in an “intermission space”, where coincidences occur and new connections can be made.

Spatial requirements relevant to creativity and innovation

In the second step of our analysis, we explored the requirements for a creative space, according to the analyzed literature. Table 2 lists the 15 identified concepts that were considered relevant to a creative space.

Among the suggested requirements are several that can be directly related to creative activities, such as a stimulating space, an engaging space that prompt participation, or the culture of a space that would reflect a specific creative identity. Playful spaces and surprising spaces were mentioned by several sources as being beneficial for creativity because they are able to trigger experimentation and instigate new connections between people. Other mentioned requirements are linked to more general workspaces and not specifically to creative spaces – for example, health and safety, or accessibility.

We can also see some overlap between categories. For example, a playful space could become some sort of stimulation or activation, and a flexible space can be considered a specific characteristic of the infrastructure. Nevertheless, we decided to keep this high level of granularity and differentiate among these similar concepts to allow for a more differentiated discussion.

Spatial design characteristics relevant to creativity and innovation

The third step of our analysis deals with the question of how exactly a creative space should be designed in order to facilitate creativity and innovation. Table 3 outlines a multitude of constructs that are considered conducive to creativity by the respective sources. We ordered the constructs roughly from large scale, such as the geographic location and architectural structures, to small scale, such as interior styles and pieces of furniture.

Figure 3 illustrates the aspects related to the geographic location of a creative workspace. Many sources suggest that a break from the daily routine or a changing workspace is beneficial to creativity because of the change of perspective this can bring about. This would explain the success of innovation labs, which provide workers with an opportunity for temporary creative retreat – away from the daily business of a company. Other relevant aspects include central locations or field access to get in touch with, for example, test users or other creative people.

Fig. 3. Number of sources mentioning geographic aspects.

Figure 4 summarizes the architectural aspects considered conducive to creativity. The two aspects mentioned most frequently in the literature were open views of nature and open-plan office spaces. Spaciousness, in general, as well as surrounding natural environments are also considered conducive to creativity. Another aspect identified as relevant is proximity of different work areas. Having to switch between spaces can result in an interrupted workflow.

Fig. 4. Number of sources mentioning architectural aspects.

Figure 5 outlines the interior aspects and individual items, such as furniture or equipment, which are considered beneficial to creativity and innovation. Here, we can draw several connections to the previously discussed spatial requirements. For example, the presence of toys and games would contribute to a playful, experimental atmosphere, while unusual furniture would lead to a surprising space. The interior aspects that were most frequently mentioned in the literature are access to tools and equipment, the opportunity to write down and display information (e.g., on whiteboards), and shared meeting rooms. A stimulating atmosphere (identified as one important requirement for a creative space in the previous section) could be achieved through plants and greenery, arts and other forms of decoration, toys and games, and vistas across rooms. Other aspects that were mentioned less frequently but that still provide interesting insights into possible spatial design solutions to trigger creativity and innovation include semi-transparent walls that create a balance between privacy and visual connections, rough materials, and a do-it-yourself style that encourages experimentation and risk-taking.

Fig. 5. Number of sources mentioning interior aspects.

Intangible aspects (ambiance) relevant to creativity and innovation

Many of the analyzed sources mention intangible or ambient aspects of a space as being relevant to creativity and innovation – including light, colors, textures, sounds, and smells. Table 4 outlines the ambiance-related concepts mentioned in the analyzed sources.

Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of sources that mention the different intangible aspects of a creative space. Here, the results are scattered. Light and sound were considered most relevant by many sources, albeit in terms of different characteristics. While natural daylight was mentioned by various sources, ambient light or artificial task light was suggested by others. Positive sound or the absence of negative sounds was mentioned most frequently. Some sources were more specific and described a lively atmosphere that includes light background music and active discussions (“buzz”) as positive. Preferences regarding colors were inconsistent. Some sources suggested bright colors, others suggested cool or pale colors, and some suggested warm colors. There seems to be no consensus in this regard. A more in-depth analysis of ambient characteristics of a creative space is needed.

Fig. 6. Number of sources mentioning intangible aspects.

Technologies relevant to creative space

Finally, we analyzed the sources according to the possibilities of new technologies to either improve the creative workspace itself or facilitate research about creative workspaces. Table 5 outlines the different technological concepts that were mentioned in the analyzed literature.

Table 5. Overview of mentioned technological aspects of a creative space

We can identify three areas that involve new technologies in the realm of creative spaces: (1) technology-enhanced creative work environments, (2) technology-enhanced research on creative spaces, and (3) technology-enhanced design processes of creative spaces. These are discussed in greater detail below.

Technology-enhanced creative work environments. As outlined in Table 5, many sources mentioned general information and communication technologies (ICT), such as computer and internet access, printing and projection equipment, and software, as part of a creative work environment. However, such an equipment can be considered standard in any modern workspace. Rapid prototyping and 3D printing facilities also fall into this category and were mostly mentioned by sources addressing the context of innovation labs (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Brinks and Brinkhoff2015; Narayanan, Reference Narayanan2017).

Moreover, AI can provide an extension of the physical space as a source of inspiration or as a knowledge repository, which could be facilitated through sensor-based objects, speech recognition, touch screens, or memorized preferences (e.g., preferences regarding light or sound settings). So-called smart spaces, including smart objects, were only mentioned by one source (Oksanen and Ståhle, Reference Oksanen and Ståhle2013). Electronic brainstorming support (Magadley and Birdi, Reference Magadley and Birdi2009) could enhance the creative output of co-workers and, hence, also falls into this category.

Technology-enhanced research on creative spaces. Machine learning in combination with fine granularity data (e.g., collected through indoor tracking or sensors) would allow for measurement of real behavior patterns and can be utilized to measure the effectiveness of a specific workspace design. Some sources present studies focusing on such measurement. Waber et al. (Reference Waber, Magnolfi and Lindsay2014) report on various studies that include the use of technological devices, such as sensors, to measure people's behavior within the workspace. They present examples of new spatial approaches used by companies like Facebook, Yahoo, Samsung, and others to enhance social interaction. One example refers to a company that reduced the number of coffee stations, forcing more people from different departments into casual meetings. This particular spatial change was correlated with a 20% increase in the company's sales.

WeWork is a US company that provides co-working spaces for start-ups, entrepreneurs, small businesses, and freelancers. They constantly try to improve their business solutions by conducting space-related research. In addition to regularly interviewing their customers to enquire about their level of satisfaction with the workspaces provided, WeWork developed several innovative research approaches to study the effects of their workspace designs (Davis, Reference Davis2016; Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2016). One example involved spatial analytics, which uses location-based data together with random enquiries (i.e., experience sampling) through apps or text messaging. Using this approach, WeWork is able to determine workspace usage statistics – for example, the average number of people using a conference room or whether spaces with more phone booths receive fewer complaints about noise distractions (Davis, Reference Davis2016).

Technology-enhanced design processes of creative spaces. New technologies are also utilized to enhance the design processes of creative workspaces. For example, Building Information Modeling (BIM), which is a software-based planning tool for architects, is being utilized to create detailed 3D models of WeWork's office spaces in order to customize and optimize their office designs and make them more efficient (Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2016).

Discussion

Theoretical and practical contributions

The analyzed literature revealed that the topic of creative environments attracts interest in various disciplines. This field is approached from different perspectives, such as theoretical investigations or prescriptive guidelines and practical tools. The majority of the analyzed sources provide only descriptions or analyses of the status quo of creative spaces (Type-1 or Type-2 theories). Some sources go a step further and also present predictions of how spatial configurations might impact creative behavior (Type-3 theories), but they do not provide explanations for the possible working mechanisms. Only four sources presented causal (Type-4) theories that provide predictions for certain impacts, theoretical explanations, as well as testable propositions. However, none of the papers appears to be comprehensive in terms of scope, empirical evidence, and theoretical underpinning, which indicates that the need for a holistic causal theory of creative spaces still persists. Similarly, the design principles (Type-5 design theories) mentioned in the sources are either insufficiently evaluated or they address a narrow target (e.g., design education). The discussed tools demonstrate that there is a need among practitioners for creative space facilitation tools. It is striking that a global software company like SAP has created their own tools (Mosaic) for this purpose, which warrants the assumption that there is a need for such tools that is currently not being satisfied. However, neither the New Workspace Playbook (Dark Horse Innovation, 2018) nor Mosaic (SAP AppHaus, n.d.) provides any theoretical underpinning, and we could not find any evidence of a rigorous development or evaluation process (although we acknowledge that the lack of a discussion or evidence of these aspects does not necessarily mean they were absent).

There are multiple links between the theory types. For example, Type-1 theories (e.g., taxonomies) can help build higher-level theories like causal theories (Type 4) by extracting different aspects of creative spaces and thereby creating a more precise vocabulary. Furthermore, effective creative space tools should be theory based.

The gaps identified in the literature present opportunities for further research. A comprehensive causal theory of the impact of spatial designs on creativity that addresses education and practice still needs to be developed. Moreover, scientifically developed tools that can guide practitioners in designing creative spaces are scarce.

Spatial characteristics

As outlined in the previous section, the analyzed literature suggests a multitude of spatial characteristics that are believed to be beneficial to creativity and innovation processes. The range of identified concepts spans from geographic aspects and architectural structures to stylistic aspects and smaller elements, such as specific furniture.

The sources mainly base these suggestions on empirical data, such as expert interviews and user assessments, or on theoretical knowledge provided by the relevant literature. However, most of the suggested spatial configurations are not validated through experimental studies.

The overview of 38 spatial characteristics, presented in Table 3, and 14 intangible aspects, presented in Table 4, provide numerous links for conducting further research. In particular, the non-physical aspects of a workspace require further investigation, as these yielded many contradictory assessments by different authors.

The multiplicity of identified concepts does not appear to allow for a comprehensive experimental study on all factors that might constitute a creative workspace because of the complexity of the topic. However, individual parameters could be separately studied – for example, in a controlled experiment. Another interesting avenue for future research is the question of whether specific spatial configurations could hinder creative work processes.

To summarize, the insights provided in this systematic literature review provide other researchers with a foundation for conducting further research on the topic of creative spaces.

Opportunities of new technologies

Many of the analyzed sources acknowledge that technologies have become a vital part of any (creative) workspace. However, most sources discuss technology-enhanced spatial solutions mainly on a level that can nowadays be considered a standard – such as virtual meeting rooms, Skype or other video conferencing systems, (wireless) internet access, as well as printing and projection equipment.

More advanced and cutting-edge equipment, such as electronic brainstorming facilities or smart spaces, are mentioned by only a few sources. Moreover, the potential for new technologies to be used in conducting research on the effectiveness of creative workspace design was not effectively exploited in the analyzed research. Due to the availability of new technologies that are becoming smaller, cheaper, and more mobile, new research approaches are emerging that could be used to measure the impact of the work environment on creativity. For example, mobile electroencephalographic (EEG) headsets that measure changes in brainwave activity could be utilized to identify the impact of particular work environments on the brain. Moreover, indoor positioning technologies can be installed to track people's movements within a space and provide insights about work preferences related to spatial design. Social media channels and crowdsourcing provide access to creative spaces worldwide. “Netnography” (Kozinets, Reference Kozinets2010), which describes the utilization of the internet for ethnographic research, enables a large number of pictures from creative spaces worldwide to be collected. Furthermore, crowd-based systems, such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (Kittur et al., Reference Kittur, Chi and Suh2008), could be utilized to have people rate pictures of creative spaces worldwide. Moreover, text mining and data mining (Hand et al., Reference Hand, Mannila and Smyth2001) allow for the automated analysis of large amounts of qualitative research data – for example, the automatic extraction of insights from design companies’ websites. Finally, experience sampling applications (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Barrett, Bliss-Moreau and Lebo2003; Hektner et al., Reference Hektner, Schmidt and Csikszentmihalyi2007) can provide study participants with a digital application on their phones through which researchers could send them prompts and surveys. This procedure would, for example, enable people to photograph their work environments and report on their self-perceived creativity within these environments. Such a study would enable user research on a larger scale and in different countries. Moreover, sensor-based measurements could be utilized to investigate people's behavior in a creative work environment. A first step in this direction was presented by Bernstein and Turban (Reference Bernstein and Turban2018), who measured co-workers’ personal interactions in an open-plan office structure based on wearable sensors. Giunta et al. (Reference Giunta, O'Hare, Gopsill and Dekoninck2018) present an overview of augmented reality (AR) technologies for design research. Thoring et al. (Reference Thoring, Mueller and Badke-Schaub2015b) present a general overview of the potentials of new technologies for design research. We can see promising possibilities for conducting future research in these areas, with the goal of conducting more quantitative research on the effectiveness of specific spatial designs.

Finally, design science approaches could also be enhanced through new technologies – a possibility that was not much addressed in the analyzed literature. For example, agent-based systems could be developed and utilized to simulate the interaction among knowledge workers based on specific spatial designs. Creative spaces could be designed virtually, or existing spaces could be altered through augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR) systems; subsequently, users would be able to give feedback on such spaces, even before they are built. Only a few sources discussed the opportunities presented by, for example, AR and VR for enhancing the design processes of creative workspaces.

Conclusions

This paper presents a structured literature review of the current research on creative workspace design. Through a systematic search process, we identified 51 academic and 22 non-academic sources for inclusion in our analysis. The sources were analyzed and discussed according to three different areas of interest. We looked into (1) the types of theoretical contributions; (2) the suggested spatial characteristics for creative work environments; and (3) the potential for new technologies to enhance the creative work, improve the development process of creative spaces, and facilitate research about creative spaces.

Our analyses revealed that most theoretical contributions were found within Type-1, Type-2, and Type-3 theories; however, causal theories, design theories, and facilitating tools were scarce. Moreover, the analyzed sources suggested six larger categories of space types that are relevant to creative work: (1) spaces for individual work, (2) spaces for collaborative work, (3) spaces for making, (4) spaces for presenting and showcasing work, (5) spaces for preparation and research, and (6) transition or break rooms. Among the identified requirements for a creative workspace, 15 categories were mentioned in the analyzed sources: social dimension, stimulation, knowledge processing, process enabling, activation, comfort, health, surprising space, playful space, flexibility, culture, ownership, accessibility, facilitation, and additional services. Furthermore, the analyzed sources suggested a total of 52 spatial design characteristics that were believed to facilitate creative work, which can be clustered into four categories: geographical aspects, architectural aspects, interior aspects, and ambient aspects. The most frequently mentioned aspects were the dislocation from the usual work environment and the break from daily routines, open views and open-plan office layouts, access to materials, writable surfaces, adequate meeting spaces, appropriate sound levels, and good light situations. The technologies for a creative work environment mostly referred to standard IT infrastructure (printing, WiFi, etc.), whereas the role of more advanced technological opportunities (e.g., AI, VR, and AR) for creative spaces were rarely discussed. The insights gained from this extensive literature review reveal numerous opportunities for further research on the topic.

One limitation of this study is that we did not include technology-related keywords into our initial search terms. This decision was taken to keep the number of returned sources at a manageable volume. As a consequence, we cannot rule out that sources with a technology focus might provide additional insights on the topic of creative workspaces. This area shall be explored further in future research. In addition, we did not include makerspaces and hackerspaces in our keyword search because these were considered to be only one part of a creative space. Future research shall explore the specifics of makerspaces in more detail, though.

The research on creative workspace design is developing quickly; new publications on the topic are released frequently. Due to the fast-moving nature of this research field, it was not possible to include the latest publications on the topic (i.e., from 2019 onwards). Nevertheless, this literature review is considered a first step toward a holistic understanding of the impact of creative workspace design on creativity and innovation. This initial step opens up a multitude of opportunities for future research that will develop this research field further.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a revised and extended version of a previously presented conference paper (Thoring et al., Reference Thoring, Desmet and Badke-Schaub2019). The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Katja Thoring is professor at Anhalt University in Dessau, Germany, and visiting researcher at TU Delft, The Netherlands. She has a background in Industrial Design and researches on topics such as creative workspaces and technology-driven design innovation.

Roland M. Mueller is professor at the Berlin School of Economics and Law, Germany, and and visiting researcher at the University of Twente, The Netherlands. He is an expert in Business Intelligence, Big Data, theory modeling, and lean design thinking.

Pieter Desmet is professor of Design for Experience at the Faculty of Industrial Design of TU Delft. He is a board member of the International Design for Emotion Society and founder of the Delft Institute of Positive Design.

Petra Badke-Schaub is professor for Design Theory and Methodology at TU Delft. She is head of the Design & Methodology section at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at TU Delft and one of the initiators of the SIG Human Behavior in Design in the Design Society.