No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2017

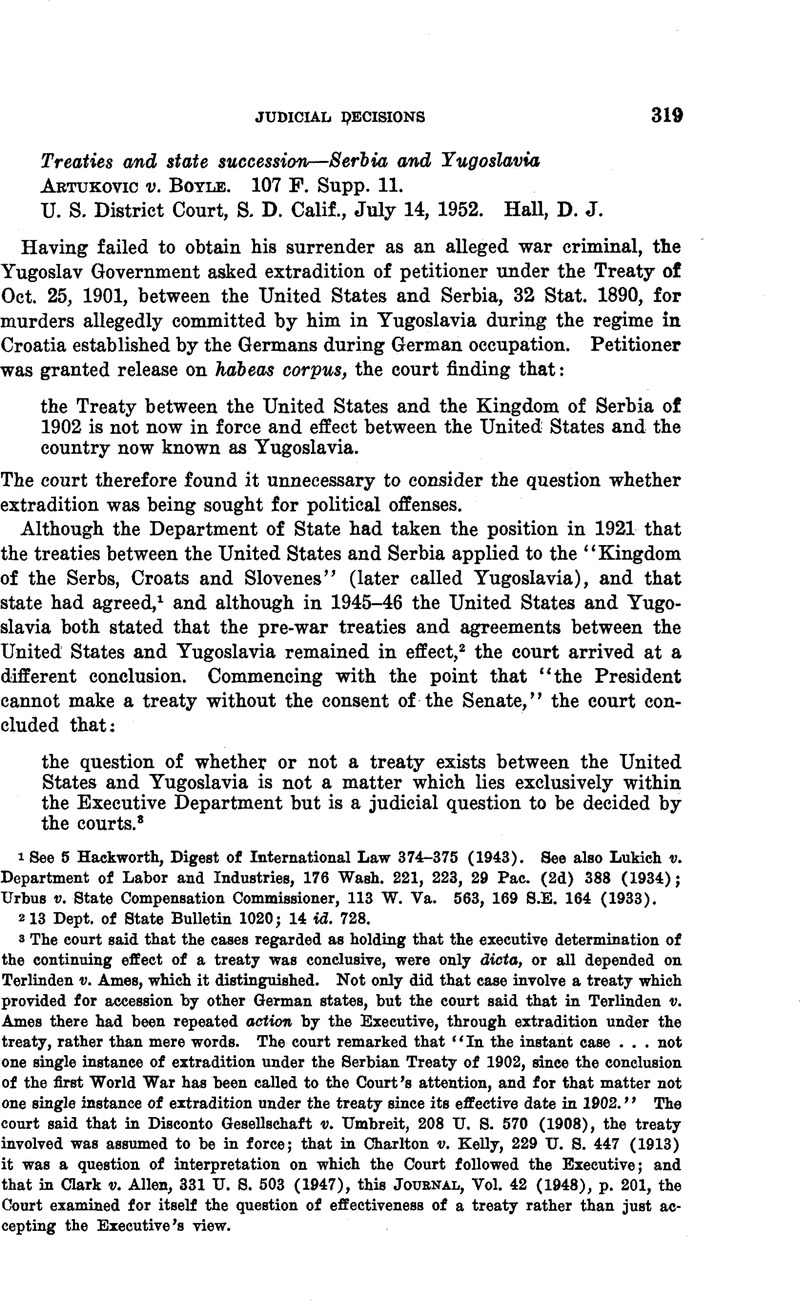

1 See 5 Hackworth, Digest of International Law 374–375 (1943). See also Lukich v. Department of Labor and Industries, 176 Wash. 221, 223, 29 Pac. (2d) 388 (1934); Urbus v. State Compensation Commissioner, 113 W. Va. 563, 169 S.E. 164 (1933).

2 13 Dept. of State Bulletin 1020; 14 id. 728.

3 The court said that the cases regarded as holding that the executive determination of the continuing effect of a treaty was conclusive, were only dicta, or all depended on Terlinden v. Ames, which it distinguished. Not only did that case involve a treaty which provided for accession by other German states, but the court said that in Terlinden v. Ames there had been repeated action by the Executive, through extradition under the treaty, rather than mere words. The court remarked that “In the instant case … not one single instance of extradition under the Serbian Treaty of 1902, since the conclusion of the first World War has been called to the Court’s attention, and for that matter not one single instance of extradition under the treaty since its effective date in 1902.” The court said that in Disconto Gesellschaft v. Umbreit, 208 U. S. 570 (1908), the treaty involved was assumed to be in force; that in Charlton v. Kelly, 229 U. S. 447 (1913) it was a question of interpretation on which the Court followed the Executive; and that in Clark v. Allen, 331 U. S. 503 (1947), this Journal, Vol. 42 (1948), p. 201, the Court examined for itself the question of effectiveness of a treaty rather than just accepting the Executive’s view.