No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2017

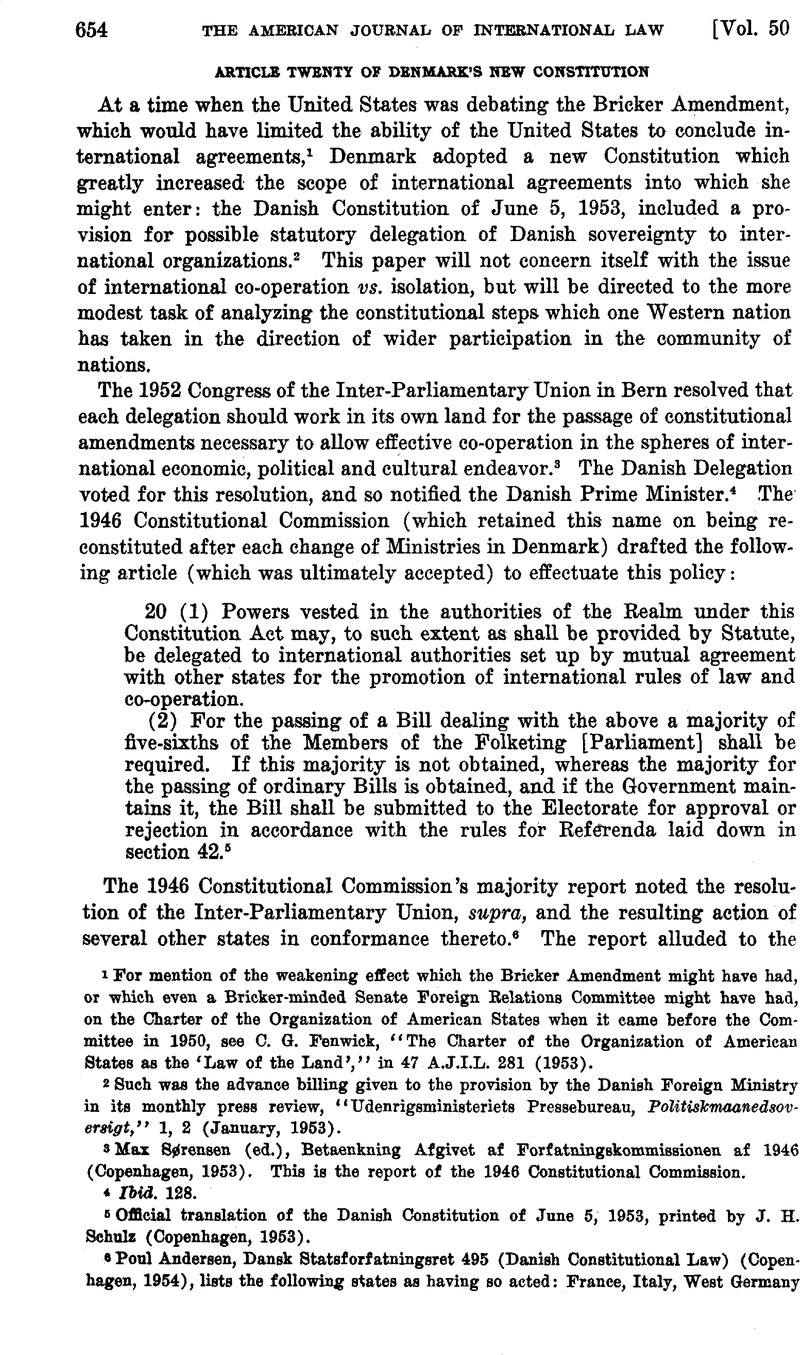

1 For mention of the weakening effect which the Bricker Amendment might have had, or which even a Bricker-minded Senate Foreign Relations Committee might have had, on the Charter of the Organization of American States when it came before the Committee in 1950, see Fenwick, C. G., “The Charter of the Organization of American States as the ‘Law of the Land’,” in 47 A.J.I.L. 281 (1953)Google Scholar.

2 Such was the advance billing given to the provision by the Danish Foreign Ministry in its monthly press review, “Udenrigsministeriets Pressebureau, Politiskmaanedsoversigt,” 1, 2 (January, 1953).

3 Sørensen, Max (ed.), Betaenkning Afgivet af Forfatningskommissionen af 1946 (Copenhagen, 1953).Google Scholar This is the report of the 1946 Constitutional Commission.

4 Ibid. 128.

5 Official translation of the Danish Constitution of June 5, 1953, printed by J. H. Schulz (Copenhagen, 1953).

6 Andersen, Poul, Dansk Statsforfatningsret 495 (Danish Constitutional Law) (Copenhagen, 1954)Google Scholar, lists the following states as having so acted: France, Italy, West Germany and Holland. For analysis of the pertinent provisions of the Netherlands Constitution, as amended on June 22, 1953, see van Panhuys, Jonkheer H. F., “The Netherlands Constitution and International Law,” in 47 A.J.I.L. 537 (1953) at 540–541, 551–552Google Scholar.

7 Argument has recently been made in Norway for a Constitutional amendment to permit delegation of legislative power to international organizations. See Loehen, Einar, Norway’s Views on Sovereignty 76 (Bergen, 1955)Google Scholar.

8 Sørensen, op. cit. 31. See also Thorborg, Johs., Rigsdagsaarbog 1952–3 (Copenhagen, 1953), at pp. 77–78, 87Google Scholar.

9 Sørensen, op. cit. 13.

10 Ibid. 77.

11 Ibid. 76. See also Thorborg, op. cit. 87–88. It is ironic that the Communist arguments on this point parallel those of the Bricker Amendment proponents in this country.

12 Udenrigsministeriete Pressebureau, Politiskmaanedsovertigt 2 (February, 1953) (see footnote 2 supra).

13 Thorborg, op. cit. 88. See footnote 18 infra.

14 Ibid. 267.

15 Svend Thorsen, Den Tredje Juni Grundlov 58 (Copenhagen, no date).

16 Andersen, op. cit. 497.

17 Ibid. 496.

18 The French translation, which may be found in 70 Revue du Droit Public et de la Science Politique 77–85 (following an article in that journal by Jacques Eobert entitled “Danemark—La Constitution du 5 Juin 1953,” at pp. 64–76), states that the delegation may be made to organizations “qui auront été créées par accord réciproque avec d’autres Etats.” Again there is an implication that Denmark must have been a charter member, as the “accord” between Denmark and other states goes to the creation, and not merely to the type, of the organization.

19 The proposal that the 30% requirement be dropped, and that the rejection be by simple majority was not accepted, as was noted earlier. Professor Andersen, op. cit. 498, criticizes the 30% requirement, arguing that the possibility of delegation of power in the face of a simple majority against delegation is in clear conflict with the strictness of the requirement of a 5/6ths majority of all Members of Parliament under the first method. Thorsen, op. cit., in an approach more journalistic than scholarly, asserts at pp. 62–63 that the general purpose of referenda is to give those who are against a particular bill which has passed Parliament a chance to express their disapproval, and that it is justifiable, therefore, to require 30% of the electorate before Parliament will be overridden.

20 Ibid. 76.

21 Furthermore, sec. (2) refers only to those referenda which are allowed under Art. 42(6), and, as we shall see, it is highly doubtful whether sec. (6) applies to Art. 20 referenda.

22 Professor Andersen, op. cit., states at p. 498, that sees. (1), (2), (3) and (7) of Art. 42 have no application to Art. 20 referenda.

23 Andersen, op. cit. 499.

24 Ibid. 498.

25 Ibid. 496. See also Sørensen, op. cit. 31, and Thorborg, op. cit. 87.

26 Thorsen, op. cit. 76.

27 One method of solution might be a decision of the Court of Impeachment (consisting of 15 Supreme Court Judges and 15 Members of Parliament). Another might be a decision of the Supreme Court. It is recognized that the Supreme Court has the power of judicial review, but it has yet to find a law unconstitutional. The operation of these courts in this area is uncertain and complex, and is beyond the scope of this paper. For discussion of the problem, see Andersen, op. cit. 450–477.

28 Thorsen, op. cit. 77. (“Det er vel netop den tredje junigrundlovs para. 20, som isaer viser, at forfatningen blev skrevet paa skellet mellem en hundredaarig fortid, hvis indhold vi kender, og en fremtid, der rejser helt nye spøfrgsmaal, til hvis løsning ogsaa Danmark maa gøre sig rede. Det var en simpel nødvendighed, at vi skabte os en ny forfatning.”)