No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

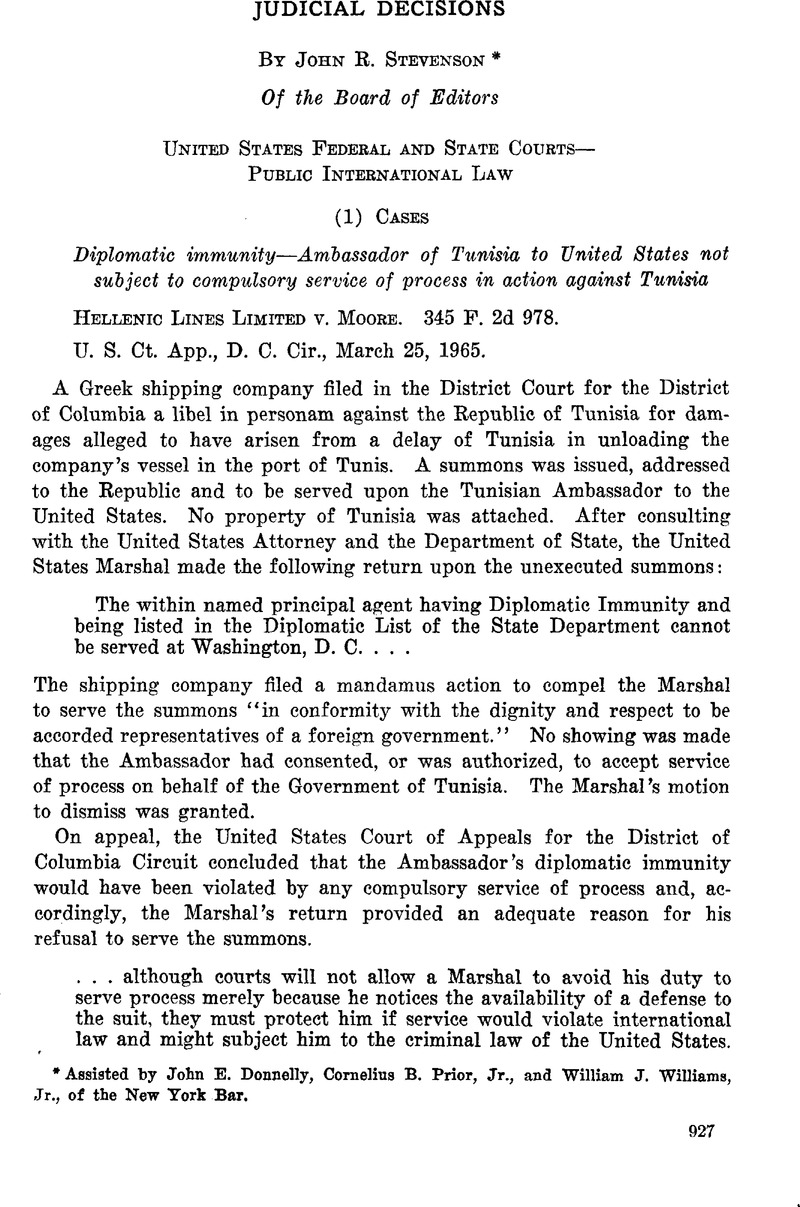

United States Federal and State Courts-Public International Law

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial Decisions Involving Questions of International Law

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1965

References

1 Article 29 of the Vienna Convention requires that ‘ ‘ The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving state shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom or dignity.” 55 Am. J. Int'l. L. 1064, 1070-71 (1961). The Vienna Convention has been signed by 63 states, including the TJnited States. I t came into force on April 24, 1964, having been finally accepted by 28 states. The treaty is now before the United States Senate for its advice and consent to ratification. See Maktos, Diplomatic Immunity,31 D.C. BAR J. 227, 231 (1964).

2 On possible impairment of a diplomatic officer's performance of official duty, the State Department said, “ I t is quite probable that such impairment would be caused; the degree of it would depend on the circumstances. An ambassador and his government would in all likelihood consider that he had been hampered in the performance of his duties if, for example, (a) the ambassador felt obliged to restrict his movements to avoid finding himself in the presence of a process server; or (b) he were diverted from the performance of his foreign relations functions by the need to devote time and attention to ascertaining the legal consequences, if any, of service of process having been made, and to taking such action as might be required in the circumstances; or (c) the manner of service had been publicly embarrassing to him and called attention to the infringement of his personal inviolability.'’ Moreover, ‘ ‘ The maintenance of friendly foreign relations between the United States and the sending state concerned would certainly be prejudiced by service of process on an ambassador against his will. The sending state might well protest to the Department that the United States had failed to protect the person and dignity of its official representative, and might complain particularly that service was by an officer of the United States Government, namely, a United States Marshal. Other governments might interpret the incident as meaning that the Government of the United States had decided, as a matter of policy, to depart from what they had considered a universally accepted rule of international law and practice.” Letter from Leonard C. Meeker, Acting Legal Adviser of the Department of State, to Nathan J. Paulson, Clerk of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, January 13, 1965 1 It is to be observed that a sovereign state has rarely been named as defendant or respondent, in suits brought in courts of this country for a money judgment against that state, as distinguished from suits based upon a seizure of property in this country claimed by the state, or counterclaims interposed after the foreign state has invoked a court's jurisdiction. So far as I am advised jurisdiction in such a suit has never been successfully obtained… .

1 United States v. California (Order and Decree), 332 U. S. 804, 805 (1947).

2 See Boggs, “Delimitation of the Territorial Sea,” 24 A.J.I.L. 541, 548 (1930).