“There’s a proverb in Malawi that says, ‘a female cow does not pull the cart, the female cow is kept for milking’”

—Joyce Banda, Malawi’s first female president“My sisters, my daughters, everywhere, find your voices!”

—Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Liberia’s first female presidentAcross the globe, female heads of government remain rare (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008; Lawless Reference Lawless2015; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015; Thames and Williams Reference Thames and Williams2013).Footnote 1 Lack of female presidents and prime ministers is a symptom of wider gender inequalities—both social and economic (Stockemer and Byrne Reference Stockemer and Byrne2011). But, as the literature on symbolic representation reminds us, a dearth of female political leadership may in itself perpetuate an image of appropriate female roles in public life (Alexander and Jalazai Reference Alexander and Jalalzai2020; Simien Reference Simien2015; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007).

Building on the work by Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo (Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012), Bauer (Reference Bauer2016, 224) defines symbolic representation as: “altering gendered ideas about the role of women and men in politics, raising awareness of what women can do as political actors and legitimizing them as political actors, or encourage women to become involved themselves in politics as voters, activists, candidates and leaders.” Whereas most research on symbolic representation has concentrated on the way in which female political role models may shape attitudes and behaviors at the mass level (e.g., Barnes and Taylor-Robinson Reference Barnes, Taylor-Robinson, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2017; Liu Reference Liu2018; Liu and Banaszak Reference Liu and Banaszak2017; Morgan and Bruise Reference Morgan and Buice2013; Zetterberg Reference Zetterberg2009), this paper focuses on the symbolic effect of a female president at the elite level. More precisely, we study how a female president may empower female members of parliament (MPs) to assert more parliamentary leadership and change their parliamentary behavior.

Women have gained increasing numerical parliamentary representation around the world (e.g., Krook Reference Krook2010; Stockemer Reference Stockemer2011). Still, some authors have questioned the extent to which increased female parliamentary representation has led to real female parliamentary leadership (Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers Reference Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers2007; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Mona2008; Weldon Reference Weldon2002). Hassim (Reference Hassim, Bauer and Britton2006, 173), writing about the role of women in African parliaments, notes that female MPs remain marginalized in parliamentary affairs through the subtle (or sometimes not so subtle) gendered hierarchies that still persist within political institutions. She argues that analysis should distinguish between “thin” and “thick” representation. Whereas thin representation relates to the mere presence of women in parliament, thick representation refers to a form of representation where women are granted real voice and power in legislative assemblies.

We argue that the presence of a female president has an important intraelite symbolic effect and enhances female thick parliamentary representation. Specifically, we argue that the presence of a female president serves to normalize female political power, redefine gendered norms about appropriate female political behavior and competences, and create momentum for more assertiveness among female MPs. In turn, these mechanisms will lead to increased thick female representation.

Empirically, we focus on the effect of Malawi’s first female president, Joyce Banda, on female thick representation. Malawi presents a unique opportunity to study how symbolic representation of a female president affects female parliamentary behavior. The most serious challenge to studying the effects of symbolic representation is that women’s election into office is commonly endogenous to the social and political context that simultaneously shape gendered perceptions of female leadership. For instance, Thames and Williams (Reference Thames and Williams2013) find that cross-nationally the probability of having a female executive is highly correlated with female legislative representation and greater history of female political participation. However, Joyce Banda was never elected to become president; she came to power by the exogenous event of her predecessor’s natural death. Moreover, her weak political position when taking office makes Malawi a suitable case for generalizations, even to cases with politically stronger female executives.

Following recent research on parliamentary behavior (Bäck, Debus, and Müller Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014; Bäck and Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2019; Blumenau Reference Blumenau2019; Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2014; Wang Reference Wang2014), we proxy thick representation by measuring gender differences in the frequency of parliamentary speech making. We make use of an original dataset of Malawi parliamentary speeches during the period 1999–2014 (covering close to 110,000 speeches) created by using innovative machine learning techniques. In our analysis, we model how the same set of parliamentarians changed their legislative behavior from the period before Malawi’s first female president (2009–2012) to the period after Malawi’s first female president (2012–2014).

In accordance with our theory, our analysis shows that women MPs speak significantly more after the inauguration of Malawi’s first female president. Moreover, we separately analyze women’s participation in debates concerning the economy. The economy is perceived as the most important issue for Malawian voters (Afrobarometer 2014) but has been stereotypically perceived as a “male” topic (Bäck, Debus, and Müller Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). Due to the electoral salience of the economy, female presidents have worked actively to redefine gendered notions of women’s inability to lead on this issue. Our analysis shows that women MPs participated significantly more often in debates on the economy after a woman became president. Finally, to assess other potential alternative explanations, we collect and analyze additional data from earlier Malawian parliamentary sessions. However, none of the alternative explanations receive any empirical support.

The paper contributes to the literature on gender and politics in several ways. First, while most research on symbolic representation has focused on symbolic effects at the mass level, we theorize intraelite consequences of symbolic representation. Second, the paper mitigates the somewhat gloomy conclusions about the limited influence that female heads of government may have in otherwise fundamentally patriarchal societies (e.g., Chikapa Reference Chikapa, Amundsen and Kayuni2016; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015; Verge and Pastor Reference Verge and Pastor2018). Third, the paper joins a growing literature (e.g., Clayton Reference Clayton2015; Wang Reference Wang2014) that uses new data and innovative research methods to place cases from new democracies within mainstream research on women in politics. All in all, our study shows that a singular focus on enhancing the descriptive representation of women in parliament is inadequate (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) and that more emphasis is needed on women’s exclusion from positions at the very top of the political hierarchy (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013; Liu and Banaszak Reference Liu and Banaszak2017).

Beyond Thin Parliamentary Representation

Research on women and legislative politics has virtually exploded in the last few decades. Whereas most of the early literature studied the role of women in local and national legislatures in advanced democracies (e.g., Dolan and Ford Reference Dolan and Ford1997; Lawless Reference Lawless2015; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005; Thomas Reference Thomas1994), newer research has increasingly focused on the prospects for increased equality in political representation in less established democracies in regions such as Southeast Asia (Liu Reference Liu2018), Sub-Saharan Africa (Bauer and Britton Reference Bauer, Britton, Bauer and Britton2006; Tripp Reference Tripp2015), the Middle East (Shalaby and Elimam Reference Shalaby and Elimam2020), and Latin America (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2010). Most research on women in legislative politics falls into two broader categories: women’s descriptive or substantive representation (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009). The literature on descriptive representation has highlighted the prevailing numeric underrepresentation of women in legislatures globally, but it has also particularly focused on how certain institutional solutions, such as gender quotas, may enhance the number of women in representative institutions (Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008). The literature on substantive representation, on the other hand, has focused more on how the interests of women citizens are advanced by increased female political representation (Chiweza Reference Chiweza2016; Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Nwankwor Reference Nwankwor2019).

However, as Hassim reminds us, enhanced female parliamentary representation may do little to promote women’s political interests if they remain marginalized within representative institutions. Despite increased descriptive representation, she concludes that women have had severe difficulties in being “taken seriously within institutions that are historically and culturally male” (Reference Hassim, Bauer and Britton2006, 173). While women may offer substantive representation and speak more on the issues of crucial importance to women citizens, their voices may still be quelled within the patriarchal culture of national legislatures.

Several accounts from around the globe have illustrated the marginalization of women within parliaments, all pointing toward the lack of thick female representation. For instance, several studies of parliamentary cultures in cases as diverse as the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Namibia have attested to frequent harassment and discrimination against women (Bauer Reference Bauer, Bauer and Britton2006; Erikson and Josefsson Reference Erikson and Josefsson2019; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005). Others have focused on women MPs’ slow career advancement and their absence in cabinets and high-prestige committees (Heath, Schwindt-Bayer, and Taylor-Robinson Reference Heath, Schwindt-Bayer and Taylor-Robinson2005; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Shalaby and Elimam Reference Shalaby and Elimam2020).

An area in which the lack of thick representation has been particularly apparent is parliamentary debates. Whereas a number of studies from around the world have highlighted how female MPs have suffered harassment and ridicule when taking to the floor (e.g., Tøraasen Reference Tøraasen2019), quantitative research has illustrated that women tend to speak significantly less than men do in parliament (Bäck and Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2019; Blumenau Reference Blumenau2019).

Much of the earlier research on women in parliament has done the important work of descriptively documenting the lack of thick female representation. Still, we know little about the ways in which women’s voices within legislative assemblies can be amplified. One existing, compelling argument in the literature relates the lack of thick representation to the general lack of descriptive representation. According to the often-cited critical mass theory, women are inhibited in their roles as legislators by their minority status. Only when female representation grows numerically can women collectively advance their position to demand greater space in the legislative process (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup1988). While there is research to support that increased female representation within parliaments or specific party groups may result in women taking to the floor more frequently (Bäck and Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2019; Yoon Reference Yoon2011), fostering thick representation by enhancing descriptive representation is, at best, an incomplete strategy. Research from countries like Sweden, where women are represented in parliament at almost the same rate as men (but where a woman has still never been prime minister), has shown that women MPs still speak significantly less in parliamentary debates than men (Bäck, Debus, and Müller Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014).

Fostering Thick Representation through Symbolic Representation

Placing the critical-mass theory aside, this paper investigates intraelite symbolic representation as an alternative pathway toward enhanced thick representation. Bauer (Reference Bauer, Olajumoke and Falola2019) has argued that symbolic representation is the least explored, but potentially most powerful path toward enhanced female political representation. Most existing research on symbolic representation has not focused on intraelite effects but instead on the effect of female political representation on mass-level public opinion and political engagement. Research has suggested several consequences of increased female parliamentary representation, such as increased female political engagement (Atkeson Reference Atkeson2003; Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007), increased likelihood in women running for office (Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015), enhanced public support for female leadership, (Burnet Reference Burnet2011), and generally greater satisfaction with democracy (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2010). Liu and Banaszak (Reference Liu and Banaszak2017) and Alexander and Jalazai (Reference Alexander and Jalalzai2020) have argued that the symbolic effects of women’s political leadership should be particularly pronounced when women take up highly visible leadership positions.

These studies on mass-level effects of symbolic representation prompt the question as to whether symbolic effects may also exist at the intraelite level. We argue that role-model effects would be particularly pronounced among women of similar social status. As argued by Liu (Reference Liu2018), when asymmetries are large between the power obtained by women in political institutions and the power obtained by ordinary women in social structures, role-model effects may be limited. However, even in highly patriarchal societies, women within political elites are likely to identify strongly with each other and model the behavior of more successful women within the same political hierarchies. When one of their fellow elite women manages to break the ultimate glass ceiling to become the head of government, this would have a particularly strong symbolic effect for parliamentary women.Footnote 2 We argue that the installation of a female president has several important intraelite symbolic effects that will promote women’s assertiveness and shape female MPs’ propensity to speak in parliament.

First, a female president has the ability to normalize the presence of women in political power. Women remain highly restricted in their political activities; women MPs are often perceived as representatives of their gender and advocates for female “special interests” (Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015). However, the presidency represents the very embodiment of male political power. When a woman takes up a position of such magnitude, it challenges the traditional understandings of female leadership being a remarkable deviation from the norm. This reduced salience of gender for female political elites should transfer from the president to other female elites, such as parliamentarians. For instance, writing about the early years of Angela Merkel’s leadership in Germany, Ferree (Reference Ferree2006, 106) notes: “She is inevitably going to contribute to changing the symbolic association of gender and politics. … Paradoxically, one of the most powerful evidences that such a change has happened already is the extent to which her gender had become unremarkable as she goes about the work of exercising political authority.”

Second, a female president can alter stereotypes about appropriate behavior for male and female MPs and challenge gendered preconceptions about suitable leadership qualities. Past scholarship has shown that men and women in leadership positions are often held to different standards when competence and leadership are evaluated. The traits that make women in leadership positions “unlikable” are the same characteristics that are often deemed necessary for leadership competence (Heilman and Okimoto Reference Heilman and Okimoto2007). This is an important dilemma. As Amanatullah and Tinsley (Reference Amanatullah and Tinsley2013, 110) succinctly put it, “those who act agentically are seen as competent but unlikable; those who act communally are viewed as likable but incompetent.” However, the presence of a female president may challenge narrow preconceptions of gender-appropriate behavior. Such changes would encourage women to participate more frequently in parliamentary debates. Furthermore, showcasing women in leadership can alter the sort of personal qualities that are associated with competence. In extension, female perspectives may be perceived as more valuable in democratic deliberation. Women in power have often drawn on maternal or matriarchic imagery to legitimize their leadership (Franceschet, Piscopo, and Thomas Reference Franceschet, Piscopo and Thomas2016). Such strategies were apparent in Joyce Banda’s rhetoric, stating for instance: “where I come from it is the woman who shoulders the biggest responsibility of supporting the family, through her contributions of labor, time, emotions and energy” (Banda Reference Banda2013).

Third, the promotion of a female president signifies a general momentum for women in politics, allowing female MPs the opportunity to advance their positions and assert leadership. Such effects have been noted in the general literature on symbolic representation, arguing that the historic marginalization of women has made women and men alike susceptible to the view that women are inferior in governing (Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004). After Joyce Banda became the president, several MPs used the installation of a female president as a declaration of victory, a call for more respect, and a demand for further advancement. For instance, Jean Kalilani, an MP of Malawi’s Dowa Central constituency (Malawi Parliamentary Hansard 2012), declared: “The question is no longer whether a woman can be president of a country or not, but rather what she can deliver. Malawi must get more and more women in decision making positions.” It should, however, be noted that women’s political momentum may be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it will embolden female MPs. On the other hand, it may also inspire backlash among male MPs, who increasingly regard women as a threat to their political careers (Krook Reference Krook2015). We still, on balance, expect that the presence of a female president will lead to women taking more assertive leadership roles, but we will refer back to this possible backlash effect in the empirical section. Based on this discussion, we formulate the following hypothesis:Footnote 3

Frequency hypothesis

When a woman becomes head of government, female MPs will speak more frequently in parliament than before.

A female president may affect not only the frequency with which women MPs speak but also the topics on which women parliamentarians access leadership. Earlier research has shown that female MPs tend to be particularly marginalized on issues that have traditionally been perceived as “masculine” or “hard” and have been foregone for appointments to cabinet and committees relating to such topics (e.g., Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1999; Shalaby and Elimam Reference Shalaby and Elimam2020). Similarly, Bäck, Debus, and Müller (Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014) show that women in the Swedish parliament are more likely to speak on issues that the authors characterize as “soft,” and less likely to speak on those issues that can be considered “hard.”

Above all, one traditional “masculine” topic that stands out is the economy. Previous research has found women to be conspicuously absent on issues related to the national economy (Bäck, Debus, and Müller Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014). This is vital for two reasons. First, voters tend to rank the economy consistently as one of the most important political issues. This is particularly true in developing economies. For instance, Clayton et al. (Reference Clayton, Josefsson, Mattes and Mozaffar2019) showed that African voters, men and women alike, rank the economy as far more important than any other issue. Women’s particularly thin representation on issues that have been considered “masculine” can be a consequence of both choice and legislative marginalization. Women may prioritize other issues than do men, particularly those that tend to overwhelmingly affect the livelihood of fellow women (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009). However, given the weight that women voters assign to the economy, we cannot explain women MPs’ relative absence on this issue as a reflection on women voters’ preferences. Secondly, given the electoral importance of this issue, women’s absence in economic debates are likely to severely hurt women MPs’ career advancement.

Research from a variety of contexts has suggested that gender stereotypes have led voters to perceive male political candidates as more competent on economic issues (e.g., Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2015). Aware of such negative stereotypes, female executives have often actively challenged them, trying to redefine the economic issue in more feminine terms. Most famously, Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom made the comparison between the national economy and a household budget to underscore her competence to deal with a struggling economy (Ponton Reference Ponton2010, 207). In other cases, particularly in the developing world, women leaders such as Joyce Banda and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf have actively pushed a more inclusive economic agenda, where female economic empowerment was placed at the core of the national development mission (Spiker Reference Spiker2019, chap. 2). Broad economic leadership from a female president and her active attempt to redefine gender stereotypes should also empower women MPs to take more active leadership on the economic issues. We, thus formulate the following hypothesis:

The economy hypothesis:

When a woman becomes head of government, female MPs will speak more frequently in parliament on the economy than before.

Case Selection and Research Design

Empirically, we leverage the case of Malawi to study the symbolic effect of a female president on thick female parliamentary representation. Joyce Banda became Malawi’s first and Africa’s second female president (after Liberia’s Ellen Johnson Sirleaf) when she entered office in April 2012. Banda was, however, never elected to the presidency. She had been the vice president since 2009, but assumed office after her predecessor, Bingu Mutharika, died in office. At the time Banda took office, she had already fallen out with the late president and had broken away from the governing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to start her own opposition party, the Peoples’ Party (PP). The rift between Banda and the DPP was so wide that top officials within the DPP, centering around the late president’s brother Peter Mutharika, unconstitutionally tried to prevent Banda from assuming office (Patel and Wahman Reference Patel and Wahman2015).

Figure 1 positions Malawi in a global and African comparison on two vital variables: the V-Dem Female Political Empowerment IndexFootnote 4 and female parliamentary representation (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman and Bernhard2020).

Figure 1. Female Political Empowerment and Female Parliamentary Representation

Note: Source: The data are from 2012. The figure only includes countries classified as electoral democracies or liberal democracies by the V-Dem Regimes of the World Index. Dashed lines represent African averages and solid lines represent global averages.

Malawi scores below both the African and global averages on the political empowerment index. This is not to say that women have been completely sidelined economically, culturally, and politically in Malawi. Indeed, much of the literature on cultural gender norms in Malawi has emphasized the importance of the country’s mostly matrilineal culture for granting political and economic access for women both contemporarily and historically in a way that has not been the case in many other African countries (Muriaas et al. Reference Muriaas, Wang, Benstead, Dulani and Rakner2019; Robinson and Gottlieb Reference Robinson and Gottlieb2021). In terms of female political representation, Malawi in 2012 is slightly above the African and slightly below the global average. From democratization in 1994 to the 2009 election, female parliamentary representation increased significantly from 7% to 22% (see Table 1). The Malawian public had also become increasingly aware of gender disparities in political representation through the 50:50 campaign, a campaign launched in the 2009 election to enhance female political representation (Kayuni and Muriaas Reference Kayuni and Muriaas2014). Nevertheless, despite acknowledging progress, Amundsen and Kayuni (Reference Amundsen, Kayuni, Amundsen and Bergen2016, 1) conclude, “Much of the traditional role of women still prevail in Malawi. She is the caretaker; her role is largely limited to the private domain, and much social and cultural prejudice against her participation in politics persists.”

Table 1. Female Parliamentary Representation in Malawi 1994–2014

Note: Source: Chimunthu Banda (Reference Chimunthu Banda2017:176).

It is not clear whether a country with relatively high or relatively low levels of gender equality could be expected to experience the largest symbolic effect of a female president on thick parliamentary representation. On one hand, one might argue that the largest effect would be observed in the most gender-unequal societies (often found in the developing world) where a female president would break the strongest with traditional gender roles. On the other hand, it might be that political gender roles would be more amendable in otherwise relatively gender-equal societies (often found within OECD countries). Findings from studies on symbolic representation in various settings do not provide clear priors.Footnote 5 Although we remain agnostic on whether more or less gender-equal cases would make for a least-likely case, we believe that the Malawian case has one critical benefit in terms of empirical generalization. While much of the literature on female executives has focused on politically strong women with considerable electoral mandates, strong political parties, and significant political clout, such as Angela Merkel, Michelle Bachelet, or Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (e.g., Ferree Reference Ferree2006; Thomas and Adams Reference Thomas and Adams2010), Banda was politically weak, her political future was unpredictable, and her party was unorganized. She also suffered from the sort of misogynistic public attacks that women in leadership positions across the world have often endured (Chikaipa Reference Chikaipa2019; Lora-Kayambazinthu and Shame Reference Lora-Kayambazinthu, Shame, Amundsen and Bergen2016). For instance, when first becoming president, former first lady Callista Mutharika, questioned her ability to rule, dismissing her as a “simple market woman.” Banda’s popularity also vanished during her term in office due to a serious economic crisis, inherited from her predecessor, and the revelation of a systemic corruption scandal, popularly referred to as “Cashgate” (Dulani and Chunga Reference Dulani, Chunga, Patel and Wahman2015). Although the corruption scandal involved both the Banda and the Mutharika regimes, and although Banda was never proven to be personally implicated, voters placed the Cashgate scandal squarely at the feet of Banda (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman, Patel and Wahman2015). Thus, it is possible that sexism directed toward Banda and her vanishing popularity may have reduced the positive symbolic effect and led to backlash against female MPs (Krook Reference Krook2015). We argue that if a politically relatively weak president like Banda could change the behavior of female parliamentarians, we would expect the same effect in cases with politically stronger executives.

The Malawi case also offers a unique opportunity in terms of internal validity. The unusual circumstances surrounding President Banda’s rise to power make Banda’s presidency exogenous to changes in perceptions concerning women’s leadership. Indeed, the endogenous nature of female political representation represents one of the greatest challenges for causal analysis of symbolic representation. Moreover, since there was no parliamentary election during this period, the same MPs were in parliament throughout the period June 2009–April 2012 (under President Mutharika) and April 2012–April 2014 (under President Banda) and there was no change in the number of female MPs.

One possible limitation of our research design is that although Banda’s appointment was exogenous, we cannot rule out the possibility that other political events happening after Mutharika’s death shaped the legislative behavior of men and women differently. However, to mitigate this risk, our analysis will also study other alternative explanations that could account for changes in female legislative behavior, using data from additional parliamentary terms.

Data and Methods

To study the legislative behavior of MPs, we rely on parliamentary transcripts, an underused resource in the African context. With the notable exception of the innovative work by Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang (Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2014; Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2017; Wang Reference Wang2014) from the Ugandan parliament, most quantitative content analyses that are based on parliamentary transcripts come from the North American or European context (e.g., Fernandes, Leston-Bandeira, and Schwemmer Reference Fernandes, Leston-Bandeira and Schwemmer2018; Proksch and Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2012).

We introduce a new dataset on speeches in the Malawian parliament for the period 1999–2014. These transcripts had not previously been made readily available to the public but were obtained through intense fieldwork and direct communication with the librarian of the parliament in Lilongwe.Footnote 6 Our collection of transcripts covers 32 parliamentary sessions. Each session represents one legislative sitting in parliament and varies in length. In total, the transcripts cover almost 110,000 speeches held by the 463 MPs in our dataset.

Given the large volume of speeches, we relied on machine learning to code their content. Machine learning has proven to be a valuable tool for social scientists, particularly for text analysis (Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Nielsen, Roberts, Stewart, Storer and Tingley2015) and text classification (Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2017; Hopkins and King Reference Hopkins and King2007). Specifically, we used a supervised learning approach. We employed transfer learning on the pretrained network BERT (Devlin et al. Reference Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang and Toutanova2018) and trained it to code the speeches based on the widely used coding scheme of the Comparative Agendas Project (Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen, and Jones Reference Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen and Jones2006). The training set consisted of 2,500 hand-coded speeches from original transcripts selected at random. We discuss our approach in more detail in the online appendix.

In our analysis, we use two dependent variables: the number of speeches made by an MP and the speeches on the economy. To create the second dependent variable, we recoded as speeches on the economy all speeches that, based on the CAP scheme, were coded as domestic macroeconomics; labor and employment; foreign trade; or banking, finance, and domestic commerce.

Independent Variables

Our main independent variable is the gender of the MP. We obtain the gender of each MP from Ott and Kanyongolo (Reference Ott and Kanyongolo2010, 412ff.) and code whether an MP is female. We are primarily interested in the interactive effect of gender and whether a speech was held during the Banda term. Our data contains eleven parliamentary sessions for the period June 2009–April 2014; sessions 1–7 occur before the Banda presidency and sessions 8–11 during the Banda term.

We also include a number of control variables. Malawi is known for having high MP turnover, particularly for female MPs (Wahman and Brooks Reference Wahman, Layla, Kanyongolo and Patel2021). Since we may expect that experienced MPs are more engaged in debates than less experienced MPs, we control for whether an MP is a newcomer. We code this variable by scanning electoral results from previous elections. We also control for important offices held by MPs. Specifically, if an MP was serving as minister, deputy minister, committee chairperson, or as part of their party’s legislative leadership,Footnote 7 they are coded as Senior MPs. We expect that women would be less likely to have ministerial portfolios (Arriola and Johnson Reference Arriola and Johnson2014) and that MPs holding such offices are more likely to appear in parliament. In models measuring the number of speeches on the economy, we control for membership in the Budget and Finance Committee. In addition, we control for whether an MP belongs to either of the two ruling parties, DPP (in the Mutharika period) and PP (in the Banda period), the main opposition party MCP, or no party if they were independent.Footnote 8 Finally, to account for time trends, we include a time variable for the number of months the government has been in office as well as its squared term. Descriptive statistics for all variables are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics

Model Estimation

For our main analyses, we use MP-month as our unit of analysis and counts of speeches as our dependent variable. Looking at the distribution of our dependent variables, we find that the standard deviation is much larger than the mean and for a large percentage of the observations the dependent variable takes the value 0. Taking into consideration the data distribution, with a large number of structural 0s, we conduct our analysis using a zero-inflated negative binomial model with standard errors clustered on the individual MP (to account for heteroscedasticity across MPs) to compare women’s and men’s speech counts during the Mutharika period and the Banda period. A possible alternative to the model-based approach we opt for here would be a difference-in-difference design; however, the structure of the data would make such an approach problematic.Footnote 9

During the Banda period, we expect that female MPs are “treated” by the fact that the president is a fellow woman. On the other hand, we do not expect this “treatment” to affect male MPs. We thus focus on the change in the number of speeches made by female MPs in the two periods and on how they compare with the number of speeches made by male MPs during the same two periods. In order to investigate these relationships, we include an interaction term between the variables Female, denoting the gender of the MP, and Banda, denoting under which government the speech took place. Our main model is specified as follows with i denoting the individual and t denoting time:

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{Number}\ {\mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{Speeches}}_{i,t} = &{b}_0+{b}_1\ast{\mathrm{Banda}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_2\ast{\mathrm{Female}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_3\ast\left({\mathrm{Banda}}_{i,t}\ast{\mathrm{Female}}_{i,t}\right)\\&+{b}_4\ast{\mathrm{SeniorMP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_5\ast{\mathrm{Newcommer}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_6\ast{\mathrm{DPP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_7\ast{\mathrm{PP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_8\ast{\mathrm{MCP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_9\ast{\mathrm{Independent}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_{10}\ast{\mathrm{Month}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_{11}\ast{{\mathrm{Month}}^2}_{i,t}+{\mathrm{e}}_{i,t}.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathrm{Number}\ {\mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{Speeches}}_{i,t} = &{b}_0+{b}_1\ast{\mathrm{Banda}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_2\ast{\mathrm{Female}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_3\ast\left({\mathrm{Banda}}_{i,t}\ast{\mathrm{Female}}_{i,t}\right)\\&+{b}_4\ast{\mathrm{SeniorMP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_5\ast{\mathrm{Newcommer}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_6\ast{\mathrm{DPP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_7\ast{\mathrm{PP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_8\ast{\mathrm{MCP}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_9\ast{\mathrm{Independent}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_{10}\ast{\mathrm{Month}}_{i,t}\\&+{b}_{11}\ast{{\mathrm{Month}}^2}_{i,t}+{\mathrm{e}}_{i,t}.\end{align}$$

Analysis

Research on parliamentary behavior around the world has found that women speak less in parliament than their male colleagues (Bäck and Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2019). This is also true in Malawi. Looking at the 2009–2014 parliament, we find that the average female MP spoke only 69% as often as the average male MP. We also find the sort of gendered differences in speech topics, observed from other countries. Figure A1 in the appendix shows speech frequency by gender broken down by speech topic. Gender differences are particularly noteworthy on economic issues. In the 2009–2014 parliament, the average female MP only made 49% as many economy speeches as the average male MP.

The noteworthy discrepancy in speech making between the genders is troubling. Not only is parliament dominated by men descriptively; female MPs are also less active in parliamentary debates. Low female activity in parliamentary debates combined with low descriptive representation means that out of the 51,981 parliamentary speeches that were made in the Malawian parliament during the period 2009–2014, 84.3% were made by male MPs.

However, the gendered patterns among the MPs with modal characteristicsFootnote 10 seem to change when Malawi gets its first female president, Joyce Banda. In Figure 2 we plot a kernel-weighted local polynomial of the female-to-male MP speech ratio on the months that the parliament was in session. This preliminary analysis shows a clear break between the Mutharika presidency, where female MPs spoke about 60% as often as male MPs, and the Banda presidency, where they spoke about 85% as often as their male counterparts. Figure 2 also fills a second important function in observing general time trends, independent of the break offered by the Banda presidency. This is important to rule out the possibility that the “Banda effect” is simply due to a generally positive time trend. The 2009 election was a breakthrough for female parliamentary representation in Malawi (Kayuni and Wang Reference Wang2014). Furthermore, members of the women’s caucus in parliament were offered various training opportunities to become more effective legislators (Adams and Wiley Reference Adams and Wylie2020; Chiweza, Wang, and Maganga Reference Chiweza, Wang, Maganga, Amundsen and Kayuni2016). These factors could have resulted in gradual and increased activity of women during the entire parliamentary term. However, Figure 2 shows no general positive time trend in the data. The female to male MP speech ratio is relatively consistent within the Mutharika and Banda periods, respectively.

Figure 2. Female to Male MP Speech Ratio over Time

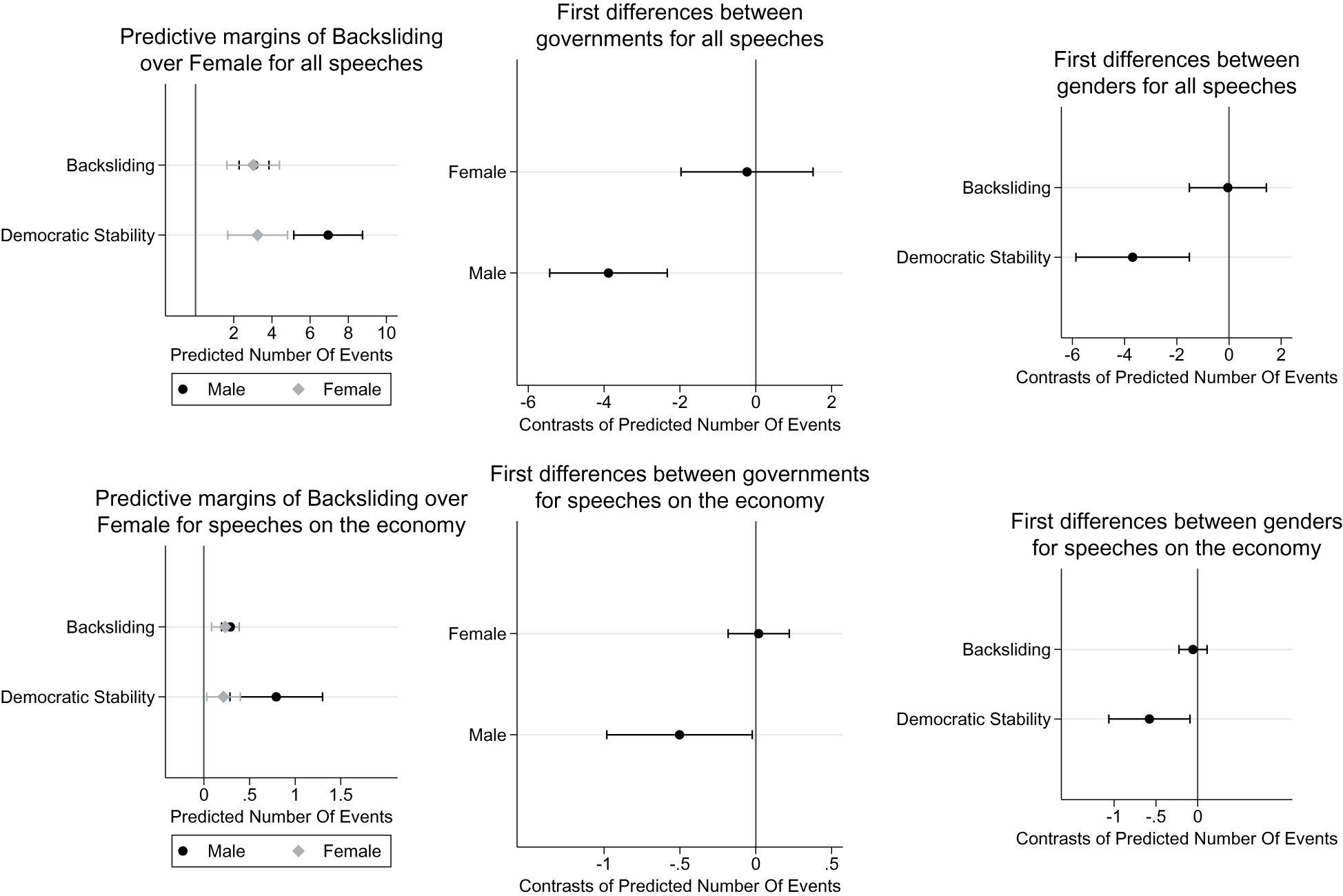

To further explore the potential intraelite effect of symbolic representation on thick female representation, we present a number of zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. We report our findings using simulations for our two main hypotheses: the frequency hypothesis and the economy hypothesis. In linear-additive regression models, the effect and statistical significance of independent variables can be interpreted directly from the table of results based on a single coefficient. However, this is not true for multiplicative interaction models like the one we present here. The most important basis for statistical inference is not the p-value of the interaction effect itself, substantive effects are better assessed through substantively meaningful simulations (Ai and Norton Reference Ai and Norton2003; Brambor, Clark, and Golder Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006). As we are mostly interested in the behavior of the typical MP, we set all variables at their mode. As a result, our estimates describe newcomer, party-affiliated (not independent), male and female MPs that do not hold ministerial office or are a part of parliamentary leadership. The estimates for the frequency hypothesis are presented in the top row of graphs in Figure 3.Footnote 11

Figure 3. Simulations Main Analysis

Note: The 95% confidence intervals are included

The top left panel of Figure 3 shows the expected number of speeches by male and female MPs during the Mutharika and Banda periods, respectively. Before we move on to interpret these results, it is worth reiterating that our hypothesis states that women will speak significantly more in the Banda term. However, if we see the same kind of increase for men, this would suggest other possible substantive explanations, not directly related to gender. It could also suggest that a woman president empowers both men and women to speak more frequently in parliament. We did not explicitly hypothesize that the gender gap between men and women would disappear (although this could potentially be the case), nor did we hypothesize that women will speak significantly more than men will during the Banda period.

During the Mutharika period, male MPs are projected to speak 5.7 times/month, while female MPs are only expected to speak 3.6 times. On the other hand, during the Banda period, male MPs were expected to speak 6.1 times and female MPs 5.9 times/month. In the middle top-row panel, we show how the expected number of speeches for men and women changes in the Banda period, compared with the Mutharika period. We find that the increase of 2.2 speeches/month for women under Banda (observed in Figure 3) is statistically significant (p = 0.027). On the other hand, men do not speak significantly more in the Banda period than during the Mutharika period. Finally, in the top right panel, we contrast the expected number of speeches made by male and female MPs over the two periods. We find that women spoke significantly less than men did during the Mutharika period but not during the Banda period. Taken together, these graphs provide sound support for our frequency hypothesis. Our main models use the number of speeches to operationalize thick representation. In the appendix, we also rerun the analysis using the number of words as our dependent variable (Figure A2). This robustness test does not yield substantially different results.

Economy Hypothesis

The bottom left panel of Figure 3 shows the expected number of speeches on the economy by male and female MPs during the Mutharika and Banda periods, respectively. During both periods, male MPs are projected to speak more often on the economy than female MPs. During the Mutharika period, the expected number of speeches per month on the economy was 0.86 for men, compared with 0.52 for women. During the Banda period, however, the gender gap is reduced, where the expected number of speeches per month on the economy was 1.06 and 0.89 for men and women, respectively.

To directly test our hypothesis, the middle graph of the bottom row contrasts the predicted number of economy speeches/month for each gender, comparing the Banda period with the Mutharika period. We find that while women increase their number of economy speeches significantly (p = 0.045) during the Banda period, there is no statistically significant difference in the number of economy speeches for men between the Mutharika and Banda periods.

Finally, the bottom right panel of Figure 3 contrasts the expected number of speeches on the economy made by male and female MPs over the two periods. We find that women spoke significantly less than men did on the economy during the Mutharika period but not during the Banda period. As a result, the analysis provides strong support for our economy hypothesis and lends further support to the theory on the symbolic importance of a female head of government. The results are not substantially different if we measure our dependent variable with number of words rather than number of speeches (Figure A2).

To further investigate changes in gendered patterns on various issues, Figures A3–A5 in the appendix replicate the same analysis for the six other topics that are most frequently discussed in the Malawi parliament. This additional analysis shows that the economy is a topic where female participation is substantially increased due to the intraelite symbolic representation effect. However, we do also find interesting variations between the Mutharika and Banda periods on two other topics that have traditionally been perceived as “male” topics: government operations and crime. We show that women spoke significantly more about government operations under Banda, we also show that there is no longer a statistically significant difference between male and female MPs in their expected number of speeches on crime during the Banda period.

Alternative Explanations

Our empirical strategy offers many advantages, but there are still limitations. Specifically, some of the effects found in the main analysis could have been related to idiosyncratic factors in the Mutharika period or other possible factors affecting women and men differently after the installation of Banda. To assess the most important alternative explanations, we collected and coded additional transcripts for the period 1999–2009 and engaged in further analysis.Footnote 12

A Mutharika Effect Rather than a Banda Effect?

First, we evaluate the possibility that the observed effect was associated particularly with the Mutharika presidency rather than the female presidency. The 2009 parliament was Mutharika’s second term after reelection in the 2009 presidential election. To evaluate whether Mutharika is an exceptional male president, we compare male and female parliamentary behavior during Mutharika’s first term in office (2004–2009) with male and female parliamentary behavior during the last term of Mutharika’s male predecessor, Bakili Muluzi. If it turns out that women spoke more under Muluzi than they did under Mutharika, the observed increase in female speech under Banda could be more a consequence of Mutharika losing office than Banda gaining it.

Figure 4 shows the results of our simulations, using the same model specification as in our main models (full results in Table A3 in the appendix). In support of our hypothesis and contrary to the alternative explanation, it does not seem like the Mutharika regime was particularly hostile toward women parliamentarians. On the contrary, the middle panel on the top row of Figure 4 shows that women spoke significantly more under Mutharika than they did under Muluzi. Furthermore, the middle panel on the bottom row shows that women spoke significantly more on the economy under Mutharika than they did under Muluzi.

Figure 4. Difference between the Muluzi and Mutharika Periods

Note: The 95% confidence intervals are included

Do Women Generally Speak More Frequently Later in the Parliamentary Term?

One potentially problematic aspect of our research design is that we compare women early on in the parliamentary term with the same women later in the same term. Although we control for earlier parliamentary experience, it may be that women without experience are more reluctant to speak early on in the term than are men without experience. Research on gender differences in communication styles has argued that women improve their ability to navigate gendered communicational expectations as they gain in experience (Pfafman and McEwan Reference Pfafman and McEwan2014).

To evaluate this potential alternative explanation, we used additional data from the two earlier parliamentary terms in our dataset (1999–2004 and 2004–2009). We divided the terms into two periods, breaking them at the half-point of the term. We thus compare women and men in the early months of the 1999 and 2004 parliaments with the same women and men in the late months of the 1999 and 2004 parliaments. Results are displayed in Figure 5 (full table in the appendix Table A4). Contrary to this alternative explanation, we do not find that women generally speak more frequently later in the parliamentary term. In fact, the opposite is true. Looking at the middle panel of the top row, we find that in the earlier Malawian parliaments both women and men actually spoke significantly less in the later part of the parliamentary term than they did in the earlier part of the same term. Looking at the middle panel of the lower row, we find that the same is true if we focus particularly on the economy.

Figure 5. Difference Early and Late Parliamentary Terms in Muluzi and Mutharika I

Note: The 95% confidence intervals are included

A Party Leader Rather than a Presidential Symbolic Effect?

President Banda was not only the president but also the leader of a major party in parliament: the Peoples’ Party (PP). No MPs were elected on a PP ticket; the party was founded by Joyce Banda in July 2011, two years after the 2009 election and only 10 months before the start of the Banda presidency. Although a few early MPs joined the party before April 2012, most PP members joined the party after Banda became president (Svåsand Reference Svåsand, Patel and Wahman2015). It is commonplace in Malawi politics that opposition MPs and independents join the ruling party to gain access to executive resources (Young Reference Young2014).

Although empirical literature on female party leaders has not unequivocally found that female party leaders are more inclined to promote the careers of female politicians (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015), some research has argued that gender dynamics within parliamentary groups may affect female legislative behavior. For instance, Bäck and Debus (Reference Bäck and Debus2019) hypothesize that women MPs in parties with higher female representation speak more frequently than their female colleagues do in more male-dominated parties. It is possible that the Banda effect can be attributed to women within PP being empowered by their female party leader and that the increased speech frequency of women MPs is related to the PP gaining in parliamentary numeric strength after Banda became president.

To investigate this possibility, we reran the analysis excluding all PP members of parliament from the analysis. The results are displayed in Figure 6. The results of our analysis remain substantially unchanged even when excluding PP MPs from the analysis.

Figure 6. Difference between the Banda and Mutharika Periods, Excluding PP MPs

Note: The 95% confidence intervals are included

To further probe the importance of political parties, Figure 7 shows the change in the female/male speech ratios for PP’s two main party rivals, DPP and MCP, during the Mutharika and Banda periods, respectively. It is possible that opposition to women’s participation would increase particularly in the DPP as misogynistic opposition to the female president grew stronger. However, this is not what we find. On the contrary, the female to male speech ratio increased in both DPP and MCP during the Banda period. Looking at nonsenior, newcomer MPs, the group that makes up the vast majority of parliament, the average DPP female MP made only 67% as many speeches as the average male DPP MP during the Mutharika period, compared with 92% during the Banda period. The corresponding averages were 71% for MCP female MPs during the Mutharika period and 91% during the Banda period. All in all, this additional analysis confirms that the symbolic effect of the female president is not confined to her own political party, but runs across parties.

Figure 7. Female to Male Speech Ratio for DPP and MCP in Mutharika and Banda Periods

Note: Bars represent male/female speech ratio for nonsenior, newcomer MPs.

Do Women Speak Less During Democratic Erosion?

The second Mutharika term was characterized by political instability and creeping authoritarianism. As the executive was put under intense pressure, the regime resorted to political repression and strengthened executive control. The extent of Malawi’s democratic backsliding was most acutely felt at the time of the July 2011 demonstrations, at which point Malawi police shot and killed 11 pro-democracy protesters (Cammack Reference Cammack2012). After Mutharika’s death, Malawi’s democracy normalized under the reign of President Banda. Banda implemented important reforms to scale back many of the draconian laws put in place by the Mutharika regime and restore the freedom of the press (Chinsinga Reference Chinsinga, Patel and Wahman2015). Could it be that women were particularly reluctant to speak in parliament during Mutharika due to eroding democracy? To investigate this alternative explanation, we study an earlier episode of democratic erosion in Malawian history, the time of President Muluzi’s third-term presidential bid. This period lasted roughly between January 2001 and March 2003Footnote 13 and has many similarities with the backsliding period under Mutharika (VonDoepp Reference VonDoepp2005). For Muluzi to pave the way for a constitutional amendment to allow for a third term in office, the government increased repression on opposition, journalists, and civil society (Cammack Reference Cammack2012). During the period, Malawi was downgraded on Freedom House’s Freedom scale from a rating of 3 to a rating of 4 on both Civil Liberties and Political Rights (higher values represent lower levels of freedom). If we find that women speak less frequently during the period of democratic backsliding under Muluzi, it could be that the effect observed in our main analysis is a consequence of the shrinking democratic space in Mutharika’s second term. Figure 8 compares the frequency of speeches between men and women during President Muluzi’s second term, comparing the period of “democratic backsliding” (January 2001–March 2003) with that of “democratic stability” (June 1999–January 2001 and March 2003–May 2004).Footnote 14

Figure 8. Difference between the Democratic Stability and Democratic Erosion Period during the Muluzi Regime

Note: The 95% confidence intervals are included

As with the other alternative explanations, we do not find any support. The middle upper-row panel shows that while men spoke significantly less during the backsliding period, there was no difference for women MPs. Similarly, the right-hand panel on the upper row shows that while women spoke significantly less than men did during the democratic stability period, there was no statistically significant difference during the backsliding period. Looking particularly at speeches on the economy, the middle panel in the bottom row of Figure 8 shows that while men spoke significantly less during the backsliding period than they did during the stability period, there is no statistically significant difference between the periods for women. All in all, these models show that, in fact, men’s advantage in speech making vis-à-vis women is greater during the stability period than it is during the backsliding period.

A Banda Backlash?

While a woman president challenges gendered stereotypes, female political advancements may also enhance the degree to which male MPs perceive their female colleagues as a threat to their own political advancement. For this reason, we might experience a backlash against female MPs (Krook Reference Krook2015). Although we have not observed a general backlash, it is possible that the symbolic effect of a female president is highly related to the popularity of the president. In cases where the female president is perceived as performing poorly, women politicians might collectively be blamed and gender stereotypes reinforced. Over time, Banda’s popularity vanished and prominent scholars of Malawi politics such as Tiyesere Mercy Chikapa (Reference Chikapa, Amundsen and Kayuni2016) have argued that Banda’s perceived failure had negative repercussions for other female politicians in their effort to gain reelection. Is it the case that the symbolic effect disappears as Banda’s popularity diminished?

Although we do not have monthly data on President Banda’s approval ratings, Afrobarometer data collected shortly after Banda’s installation and just before the 2014 election make clear that Banda’s popularity was reduced significantly during her term in office (Dulani and Chunga Reference Dulani, Chunga, Patel and Wahman2015). It is hard to pinpoint exactly when Banda’s popularity drops, but it is widely believed that the Cashgate corruption scandal revealed in September 2013 was a decisive moment associated with Banda’s fall from grace (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman, Patel and Wahman2015). In Figure 9, we break the Banda presidency into a pre-Cashgate and a post-Cashgate period. Although women speak less post-Cashgate, we see an even larger reduction in the number of speeches for men. In fact, the predicted difference in the number of speeches between men and women is smaller in the post-Cashgate period than it is in the pre-Cashgate period (the difference between men and women remains statistically insignificant in both periods). In other words, the intraelite symbolic effect persists despite the female president’s reduced popularity.

Figure 9. Difference between the Pre- and Post-Cashgate period during the Banda Regime

Note: The 95% confidence intervals are included

Conclusion

Although women’s descriptive representation in parliament has increased globally, women are still lacking in thick representation (Hassim Reference Hassim, Bauer and Britton2006). Much important work has been conducted to describe the form of obstacles faced by female legislators around the world, but we still need more research that identifies paths toward enhanced thick female representation. As argued by previous researchers, increasing female descriptive representation is insufficient (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009; Weldon Reference Weldon2002). Women legislators, even in practically gender-balanced parliaments, still possess less voice than their male colleagues do in vital parliamentary debates (Bäck, Debus, and Müller Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014). This paper has offered a new path toward enhanced thick parliamentary representation: intraelite symbolic representation.

We argue that elite women will find inspiration from other more successful women within the same political hierarchies. The presence of successful women at high positions in political hierarchies has the ability to redefine the role of women in politics, challenge perceptions of male and female leadership, and create a general momentum for women in politics. Looking particularly at the importance of Malawi’s first-ever female president, Joyce Banda, we showed that having a woman president led to women occupying more space in parliamentary debates and being less confined in their parliamentary roles.

To be sure, our study still leaves many questions about intraelite symbolic representation to be answered by future work. Most importantly, further explorations of causal mechanisms would certainly help in establishing more precise links between female leadership and women’s empowerment within political institutions. Much of this work is likely to be at the micro level and should also consider studying the effect of female leadership on male and female elites, respectively (e.g., Schwindt‐Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2010). More work is particularly needed on the ways in which male elites may respond negatively to female political empowerment (Krook Reference Krook2015).

Second, future work should also consider similar intraelite symbolic effects at other levels of political hierarchies and within institutions other than national parliaments. For instance, research has pondered the ways in which female chiefs (Bauer Reference Bauer2016) or female justices (Dawuni and Kang Reference Dawuni and Kang2015) may inspire female leadership within other political institutions.

Third, looking more specifically at legislative politics, more work is also needed to study the ways in which formal institutions may mitigate positive intraelite symbolic effects. Particularly, one may hypothesize that such effects may be affected by the presence of gender quotas (Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2014) or be quelled by highly structured parliamentary speech-making procedures giving significant power to male gatekeepers (Proksch and Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2012).

Fourth, this paper studies the effects of a first-ever female president. The novelty of a first-ever female president is likely to have the greatest short-term influence on female parliamentary behavior (Schwindt-Bayer and Reyes-Housholder Reference Schwindt‐Bayer and Reyes-Housholder2017). Nevertheless, future work from countries where female executive power is more normalized through repeated and/or long spells of female executive power may study both the short-term effects of having a female executive in office and the long-term effects of accumulated experience of female executive power (see also Beauregard Reference Beauregard2018).

Overall, we believe that this study has wide implications for debates on women in politics. Our findings stress the interconnected nature of political representation at various levels of government and highlight the need to study these institutions in tandem. Previous research has questioned the role of women in executive positions in enhancing women’s descriptive representation in legislatures and cabinets (Chikapa Reference Chikapa, Amundsen and Kayuni2016; O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). Our argument is considerably more optimistic about the role of female executives in enhancing women’s political representation. Focusing on thick, rather than thin, representation, we show how a female president may enhance the political role of women by changing the nature of political representation for women already present within male-dominated political institutions. The concept of intraelite symbolic representation was applied here to the highest levels of government, but there is little reason to believe that such effects are limited to this level. Our results confirm that real political empowerment diffuses between institutional levels and that a singular focus on increasing women’s descriptive representation in parliament may not be enough for reaching political gender equality within contemporary democracies.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S000305542100006X.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files are available at the American Political Science Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DZWOCK.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, the 2018 University of Aarhus Challenges to Democratization Workshop, the 2019 Gender, Political Representation, and Development in Africa Conference at University of Ghana, the 2019 Comparative Agendas Project Conference in Budapest, and at the Michigan State University Comparative Politics Seminar. We are grateful for invaluable comments and support provided by Frank Baumgartner, Sarah Brierley, Ruth Carlitz, Nicholas Cheeseman, Aaron Erlich, Erica Frantz, Manolis Frantzeskakis, Hamida Harrison, Andrew Kerner, Staffan Lindberg, Anna Lührmann, Valeriya Mechkova, Shahryar Minhas, Nandini Patel, Christina Scheller, Merete Bech Seeberg, Peter VonDoepp, and three anonymous reviewers. We are also hugely indebted to the Chief Parliamentarian Librarian in Lilongwe, Maxwell Banda, and the Malawi Clerk of Parliament, Fiona Kalemba. Invaluable research assistance was provided in Malawi by Felix Chauluka and Fannie Nthakomwa. We are also grateful to two dedicated teams of undergraduate research assistants: one team at University of Missouri, including Andrew Gilstrap, Trent Hall, Katie Mechlin, Seamus Saunders, Tricia Swartz, Momoko Tamamura, Mandy Trevor, Hunter Windholtz, and Hanna Wimberly and one team at Michigan State University including Layla Brooks, Cooper Burton, Isaac Cinzori, and Anthony Luongo.

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The authors affirm that this research did not involve human participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.