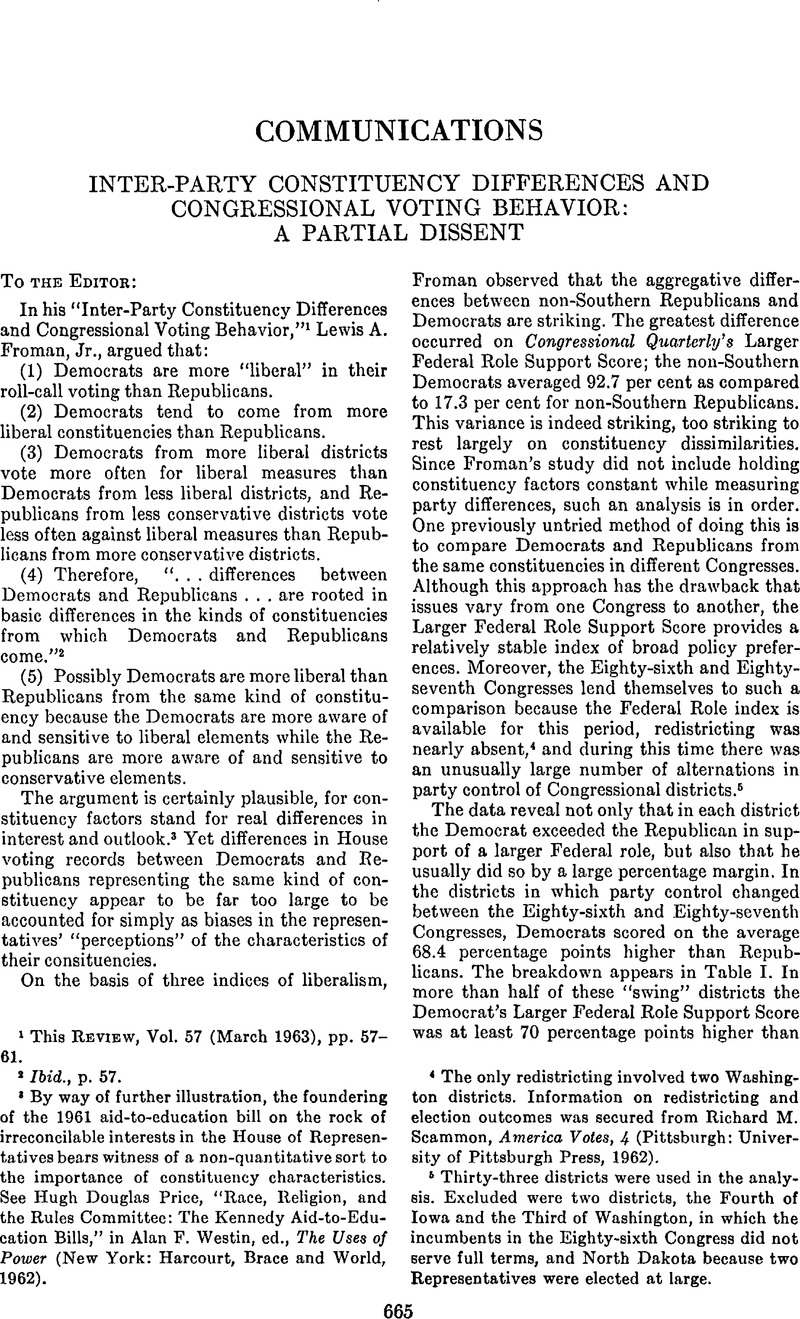

Article contents

Inter-Party Constituency Differences and Congressional Voting Behavior: A Partial Dissent

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Communications

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Political Science Association 1963

References

1 This Review, Vol. 57 (March 1963), pp. 57–61.

2 Ibid., p. 57.

3 By way of further illustration, the foundering of the 1961 aid-to-education bill on the rock of irreconcilable interests in the House of Representatives bears witness of a non-quantitative sort to the importance of constituency characteristics. See Price, Hugh Douglas, “Race, Religion, and the Rules Committee: The Kennedy Aid-to-Education Bills,” in Westin, Alan F., ed., The Uses of Power (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1962)Google Scholar.

4 The only redistricting involved two Washington districts. Information on redistricting and election outcomes was secured from Scammon, Richard M., America Voles, 4 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1962)Google Scholar.

5 Thirty-three districts were used in the analysis. Excluded were two districts, the Fourth of Iowa and the Third of Washington, in which the incumbents in the Eighty-sixth Congress did not serve full terms, and North Dakota because two Representatives were elected at large.

6 Cf. Samuel P. Huntington, “A Revised Theory of American Party Politics,” this Review, Vol. 44 (September 1950), pp. 669–677.

7 Op. cit., p. 60.

8 In the Northeastern (New England plus New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) “swing” districts of 1958–60 the average difference between Democrats and Republicans was only 54.9 per cent compared to a difference of well over 70 per cent in each of the other regions. The smaller difference in the Northeast is due to higher Republican scores, which averaged 37.7 per cent. The same regional pattern emerges if all Republican Representatives are compared or if Republican Senators are compared.

- 1

- Cited by

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.